Abstract

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway has emerged as an important regulatory mechanism governing the activity of several transcription factors. While estrogen receptor α (ERα) is also subjected to rapid ubiquitin-proteasome degradation, the relationship between proteolysis and transcriptional regulation is incompletely understood. Based on studies primarily focusing on the C-terminal ligand-binding and AF-2 transactivation domains, an assembly of an active transcriptional complex has been proposed to signal ERα proteolysis that is in turn necessary for its transcriptional activity. Here, we investigated the role of other regions of ERα and identified S118 within the N-terminal AF-1 transactivation domain as an additional element for regulating estrogen-induced ubiquitination and degradation of ERα. Significantly, different S118 mutants revealed that degradation and transcriptional activity of ERα are mechanistically separable functions of ERα. We find that proteolysis of ERα correlates with the ability of ERα mutants to recruit specific ubiquitin ligases regardless of the recruitment of other transcription-related factors to endogenous model target genes. Thus, our findings indicate that the AF-1 domain performs a previously unrecognized and important role in controlling ligand-induced receptor degradation which permits the uncoupling of estrogen-regulated ERα proteolysis and transcription.

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway contributes to the control of transcription through the ubiquitination and regulated degradation of multiple components of the transcriptional machinery (10, 34). Among these components is a large list of transactivators whose activity can be related to their proteolytic degradation. For many, particularly those that possess acidic activation domains, such as VP16 and c-myc, sequence elements essential for proteasome-mediated proteolysis reside within transactivation domains (33, 43). Several members of the nuclear receptor superfamily are substrates for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (11, 19, 21, 24, 26, 29, 37, 50, 52, 55), the first identified being estrogen receptor α (ERα) (1, 13, 36). ERα possesses two transactivation domains, AF-1 and AF-2, which reside in the N terminus and C terminus of the receptor, respectively. These activation domains are bridged by a conserved DNA binding domain and a hinge region responsible for receptor nuclear localization.

The transcriptional activity of AF-2 is strictly ligand dependent, but the AF-1 is not; thus, AF-2 received much attention for analysis of the relationship between estrogen-stimulated proteolysis and transcription. AF-2 is highly structured, consisting of 12 α-helices that adopt an active conformation upon agonist binding, which exposes a hydrophobic surface where coactivator proteins bind (6). It has been shown that mutations of residues critical for AF-2-mediated transactivation disrupt proteolysis (27, 53). E6-AP, a ubiquitin ligase (35), and the TRIP1/Rpt6/SUG1 (28, 42) subunit of the 19S regulatory cap of the proteasome bind to ERα through the coactivator binding domain, and overexpression of these factors increases ligand-dependent ERα transcriptional activity. Conversely, knockdown of the coactivator AIB1 was found to stabilize ERα protein and inhibit association of receptor with E6AP (45). Lastly, results from Reid et al. demonstrate that inhibition of ERα transcriptional activation correlates with inhibition of receptor degradation, and, reciprocally, proteasome inhibitors prevent recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to ERα-bound promoters (41). These findings support the sequential model of proteolysis and transcription in which the assembly of coactivators with ERα begins the recruitment of specific ubiquitin E3, which is followed by receptor ubiquitination, recruitment of a regulatory subunit of the proteasome, consequent degradation of the receptor complex, and final transcriptional events. The model also implies that the ligand-binding and AF-2 domains may be sufficient for ligand-induced ERα degradation. However, whether or not other regions of ERα also impart a dominant control on ERα degradation remains undefined.

While a direct mechanistic connection between ERα degradation and transcriptional activity is attractive, there are observations that do not seem to be consistent with this model. Early studies of ERα transcriptional function utilized the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide as a standard means to demonstrate primary gene targets of ER-directed transcription (5, 46, 47). Yet, cycloheximide surfaced as an effective inhibitor of E2-induced degradation (4, 14). Disassociation of hormone-inducible proteolysis and transcription has also been observed in studies of prolactin gene expression where both thyroid hormone and certain proteasome inhibitors were shown to inhibit E2-induced degradation of ERα without affecting prolactin gene induction (2). In addition, recent data further demonstrated that induction of pS2 gene expression by estrogen in MCF-7 breast cells was not inhibited despite a blockade of proteasome-dependent degradation (15). These data illustrate that the signaling of proteolysis and transcriptional activity of ERα can be separated under certain experimental settings. Thus, direct coupling of ERα degradation and transcription needs further analysis. In particular, investigation of other regions of ERα, especially AF-1, may reveal underlying relationships governing these regulatory mechanisms.

Here, we examined the role of regions of ERα outside the C-terminal ligand-binding domain and AF-2 by means of a series of mutagenesis experiments. We identified mutations of S118 in the AF-1 domain to differentially modulate estrogen-induced ubiquitination, degradation, and transcriptional activity of ERα. Distinct activities of ERα mutants correlated with a divergence in the regulated recruitment of specific ubiquitin E3 ligases, transcriptional coactivators, and other transcription-related factors to target gene promoters. Thus, our findings indicate that S118 of the AF-1 domain performs an important role in estrogen-mediated ERα proteolysis by regulating differential recruitment of factors mediating proteolysis and transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Standard cell culture conditions consisted of maintenance of cells at 10% CO2 at 37°C in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratory, Logan, UT), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD).

Generation of stable cell lines.

Stable cell lines were generated by calcium phosphate transfection of HEK293 cells with LHL-CA-ERα expression constructs. ERα mutants were cloned into the BamHI/XhoI site of the LHL-CA expression vector, which confers hygromycin resistance and drives expression of ERα under the control of a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-actin promoter (32). S118A-ERα (HE457) and S104/106A-ERα were generously provided to us by Pierre Chambon and Benita Katzenellenbogen, respectively. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were selected with 200 μg/ml hygromycin. Cell colonies were isolated and screened for ERα protein expression by Western blot analysis. Multiple clones were generated for each ERα variant. Quantitative analysis of ERα levels represents values from experiments performed with multiple clones to account for potential clonal variation.

Hormone treatments.

In experiments involving 17β-estradiol (E2) or ICI182,780 (ICI), cells were transferred to phenol red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped serum for a minimum of 3 days prior to hormone addition. To assess ERα degradation, cells were treated with 10 nM E2 or ICI for 4 h, except where indicated otherwise. In reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) experiments, cell exposure to 10 nM E2 was done for 3 h, except in the case of cathepsin D (CATSD), where gene induction by E2 required 16 h of hormonal treatment.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were performed on samples treated with E2 for 3 h. Control vehicle samples were treated with equivalent volumes of ethanol. Estrogen was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO), and ICI was a gift from Jack Gorski.

Western blot analysis.

Western blots were performed as previously described (1). The protein concentration of whole-cell lysates was determined by Bradford assay. Blots were probed with saturating concentrations of primary antibodies to ERα (HC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were reprobed with antiactin antibody (AC-15; Sigma Chemical Co.) to ensure equivalent loading of samples. Protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Band intensities were quantified by optical density analysis (LabWorks 4.0 Image Acquisition and Analysis Software; UVP BioImaging Systems, UVP Inc., Upland, CA). Relative ERα levels are presented as a percentage of the receptor levels in vehicle-treated controls and represent the mean and standard errors from a minimum of three independent experiments.

Transient transfection.

Mutants of ERα (S118E, S167A, K48R, K171R, K180R, K-null) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of wild-type (WT) ERα using a Quik Change kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), verified by sequencing at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center, and subcloned into the LHL-CA expression vector (see above) for functional analysis. HEK293 cell lines were transiently transfected using calcium phosphate with the indicated ERα mutants. Transcriptional activity was determined by reporter gene assays in samples cotransfected with the indicated ERα expression plasmid, ERE-tk-Luc (51), and the cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase expression construct (CMV-βgal) following a 24-h treatment with either E2 or ethanol (EtOH). Luciferase (Luc; Luciferase Assay System; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) and β-galactosidase activity (Galacto-Light Plus, Tropix, Inc., Bedford, MA) were measured as per the manufacturers' instructions. Luciferase values were normalized against β-galactosidase activity to control for transfection efficiency. Data represent the average and standard error of three independent experiments.

Ubiquitination assay.

Stable HEK293 cell lines expressing ERα (wild type, S118A, and S118E) were placed in medium containing dextran-charcoal-stripped serum for 3 days prior to treatment. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) for 30 min to block proteasome activity. Cells were then treated with 0.1% EtOH or 10 nM E2 for 4 h. Following treatment, cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1% NP-40, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Lysates were boiled immediately for 10 min followed by centrifugation. Immunoprecipitations were carried out using anti-ERα antibody (HC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and protein A-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia). Beads were washed four times in lysis buffer and boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were boiled in transfer buffer for 15 min and probed for ubiquitinated ERα using antiubiquitin antibody (P4D1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Boiling the blots enhanced detection of the ubiquitin epitope by the antiubiquitin antibody. To ensure the integrity of the proteasome pathway in the various ERα-expressing cell lines, an equivalent number of cells were treated with 10 ng/ml tumor necrosis factor (TNF) for 10 min following pretreatment with 10 μM MG132. Western blot analysis of total cell extract was then performed using anti-IκBα (C-21, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Long exposure allowed visualization of ubiquitinated IκBα.

RNA isolation and quantification.

Total RNA from 10 × 106 cells was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and treated for 1 h with DNase (Roche). Following quantification, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using poly(dT) oligonucleotides. The sequences of the primers used for the PCR-mediated amplification of the different genes of interest are as follows: pS2-5′, ATGGCCACCATGGAGAACAA; pS2-3′, TAAAACAGTGGCTCCTGGCG; C3-5′, CCATCCTCTCCCTCTGTCC; C3-3′, CATGGGACTCCCCAGAGCCAGG; CATSD-5′, GACACAGGCACTTCCCTCAT; CATSD-3′, GGACAGCTTGTAGCCTTTGC; ER-5′, CAGCATGTCGAAGATCTCCACCA; ER-3′, GAATCTCCATGATCAGGTCCACCTTC; universal PO 5′, AAYGTGGGCTCCAAGCAGATG; universal PO 3′,GAGATGTTCAGCATGTTCAGCAG; GAPDH-5′, TCTGGTAAAGTGGATATTGTTG; and GAPDH-3′, GATGGTGATGGGATTTCC. Quantitative PCRs were performed using an ABI Prism 7000 apparatus (Applied Biosystems) with 60 cycles of three-step amplification. Data for three independent experiments are shown as a percentage of the maximal level of estrogen-induced gene expression determined in the first experiment.

ChIP assays.

Chromatin cross-linking, purification, fragmentation, and subsequent ChIP assays were performed as described by Métivier et al. (30) following a 3-h treatment with 10 nM E2, with the sonication step using a Sonifier cell disruptor (Branson, Danbury, CT) at maximum settings with 5 cycles at 50% duty. Antibodies raised against p68 were a gift from F. Fuller-Pace; those targeting human ERα (hERα; HC-20), cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (cdk7; FL-346), SRC1 (C-20), p300 (N-15), MDM2 (D-12), and E6-AP (H-182) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; and those raised against TRIP1/Rpt6 (clone p45-110 #PW9265) and p-Pol II (Clone CTD4H8 #05-623) were from Affiniti Research (Exeter, Devon, United Kingdom) or Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA), respectively. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used in the PCRs following the presence of the three promoters of interest in the immunoprecipitated material are as follows: pS2 −350, 5′-GTTGTCAGGCCAAGCCTTTT-3′; pS2 −30, 5′-GAGCGTTAGATAACATTTGCC-3′; hC3 −260, 5′-GAGAAAGGTCTGTGTTCACCAGG-3′; hC3 +28, 5′-TCTGTCCCTCTGACCCTGCA-3′; CATSD −190, 5′-CCAGGGTGGGCCGCCCCACGACC-3′; and CATSD −62, 5′-TAGGCGCGGCAGGCGCACCACCACC-3′. Quantitative PCRs were performed using a Bio-Rad MyIQ apparatus and iQ SYBR GRN SUPERMIX (Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France). The oligonucleotides used were similar to those described above in the case of the pS2 promoter, with those for the C3 being C3 −216 (5′-TTCTCCAGACCTTAGTGTTC-3′) and C3 −66 (5′-CTCAGGTTACTCACCCCA-3′).

Statistical analysis.

Significant differences between groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Student's t test between individual groups using Microcal Origin software (Northhampton, MA). Differences with P values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant. The statistics performed for individual experiments and the P value scores are indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

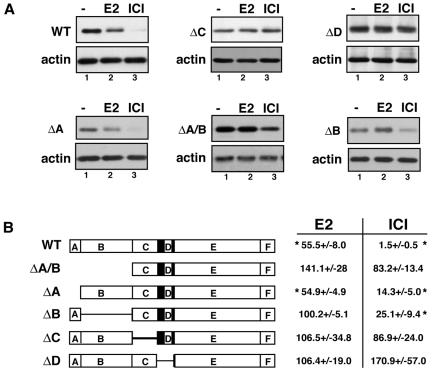

Both N and C termini of ERα are required for E2-stimulated ERα degradation.

Deletion analysis was undertaken to identify regions of ERα that are critical for estrogen-induced proteolysis. ERα is composed of six well-defined modular domains, A to F, each of which has an assigned function (23). Because we and others previously demonstrated the importance of ligand binding and an intact AF-2 to ERα proteolysis (27, 40, 53), the focus of deletion mutagenesis was placed on the remaining four regions while the E/F domain was left intact. HEK293 cell lines were created that stably express WT or ERα deletion mutants. To assess susceptibility to ligand-induced degradation of receptor, cells were treated with E2 or ICI for 4 h, followed by Western blot analysis on whole-cell lysates for ERα and the loading control, actin (Fig. 1A). We showed previously that within this time frame, estrogen induces proteasome-dependent degradation of ERα protein in pituitary and breast cancer cell lines, which is apparent in a decrease in the ERα steady-state levels (1). Consistent with our previous findings, HEK293 cells expressing wild-type ERα responded similarly by downregulating ERα protein to approximately 55% of control levels in the presence of estrogen (Fig. 1B). Also consistent with earlier reports, ICI was more effective at stimulating ERα degradation than E2 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, deletions of the DNA-binding domain (C domain) and hinge region (D domain) resulted in a complete abrogation of ligand-induced downregulation. Estrogen-induced ERα degradation was also prevented by deletion of the A/B and B domains, but loss of the A domain had little impact.

FIG. 1.

HEK293 cell lines stably expressing WT ERα or truncation mutants with deletions of the A/B (ΔA/B), A (ΔA), B (ΔB), C (ΔC), and D (ΔD) domains were treated with EtOH (lane 1), 10 nM E2 (lane 2), or 10 nM ICI (lane 3) for 4 h. ERα protein levels were next examined by Western blot analysis. (A) Representative Western blots showing ERα levels following hormone treatment. Actin levels served as an internal control for equivalent loading of samples. (B) Schematic illustration of the domain structure of wild-type and ERα deletion mutants with the levels of expression of these different proteins shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean relative to EtOH vehicle controls. The data represent values from three or more independent experiments. Student's t tests were performed to determine statistical differences between vehicle and ligand-treated samples (*, P < 0.05).

In comparison, ICI-induced receptor degradation was impaired in all ERα deletion mutants relative to WT-ERα. However, despite these differences, ICI treatment significantly decreased the relative levels of ERα compared to vehicle and estrogen-treated controls in both the ΔA and ΔB ERα mutants (Fig. 1B). Thus, while deletion of the DNA binding domain and hinge region negatively impacted regulated destruction of ERα protein, the ΔB ERα mutant was completely resistant to E2-induced degradation but permitted ICI-induced degradation, albeit diminished relative to wild-type controls.

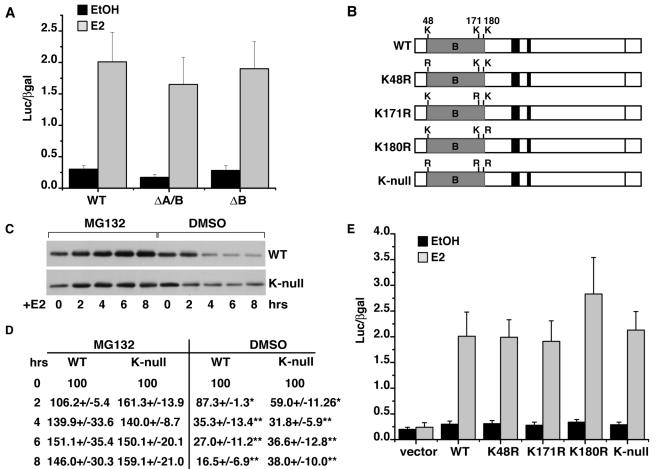

Lysines in the B domain are not essential for ERα degradation and transcription.

Previous studies had shown that loss of the N-terminal A/B domain does not interfere with estrogen-inducible transcriptional activity in certain cell contexts (18, 31). In our model, the ΔA/B and ΔB receptor mutants retain significant estrogen-inducible transcriptional activity despite being resistant to degradation (Fig. 1 and 2A). Thus, we turned our analysis to the B domain. We reasoned that the defect in ΔB ERα might be due to loss of a critical site of ubiquitination. Ubiquitination typically occurs on preferred lysine residues of the substrate targeted for destruction (39). Sequence comparison of the B domain of ERα in human, mouse, rat, chicken, and Xenopus showed the presence of three conserved lysine residues which correspond to K48, K171, and K180 in human ERα. Thus, four ERα point mutants were generated in which each of the three lysines was mutated to arginine individually (K48R, K71R, K180R) and in total (K-null) in the context of the full-length receptor (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis of receptor protein in stable HEK293 clones expressing WT and K-null receptor variants shown in Fig. 2C illustrate that an ERα mutant devoid of lysines in the B domain is efficiently degraded in response to E2 over a time course of 8 h. Both WT and K-null ERα showed decreases in receptor levels which were significantly different from those of vehicle-treated controls within 2 h but were not significantly different from each other (Fig. 2D). Similar results were observed for each of the individual mutants (data not shown). Moreover, treatment with proteasome inhibitor MG132 prevented E2-induced decreases of WT and K-null receptors, providing evidence that in both cases estrogen-stimulated decreases in ERα protein are dependent on proteasome activity. Consistent with earlier reports, MG132 treatment increased ERα levels above controls, reflecting effects on both estrogen-induced and basal turnover of receptor (1, 36, 49). E2-stimulated induction of an ERE-driven reporter gene was also similar between each of the lysine mutants and wild-type ERα (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that the lysine residues within the B domain are dispensable for both ligand-inducible transcriptional function and receptor degradation.

FIG. 2.

(A) The transactivation capacity of WT and ΔA/B-ERα proteins was tested by transient transfection analysis of an ERE-tk-Luc reporter gene. Cells were transiently transfected with reporter gene plasmids encoding ERE-tk-Luc and CMV-βgal reporter plasmids along with the indicated ERα variant. Treatment with either EtOH or 10 nM E2 proceeded for 24 h. Luciferase values were normalized for transfection efficiency against β-galactosidase activity. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean of a minimum of three independent trials. (B) Schematic map of ERα B domain showing three conserved lysine residues and the names of ERα mutants in which the lysine residues were mutated to arginine. (C) Stable HEK293 cell lines expressing WT or K-null ERα were treated with 10 nM E2 for the indicated time following a 30-min pretreatment with 10 μM MG132 or vehicle, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Shown is a representative Western blot of whole-cell lysates probed for ERα or actin as a loading control. (D) Band intensities of Western blots from experiments in panel C were quantified as described in Materials and Methods and normalized against actin loading controls. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean for three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were determined by Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (E) Reporter gene assays were carried out as in panel A with the indicated ERα mutant. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error for three independent trials. There are no statistical differences in reporter gene activity between groups.

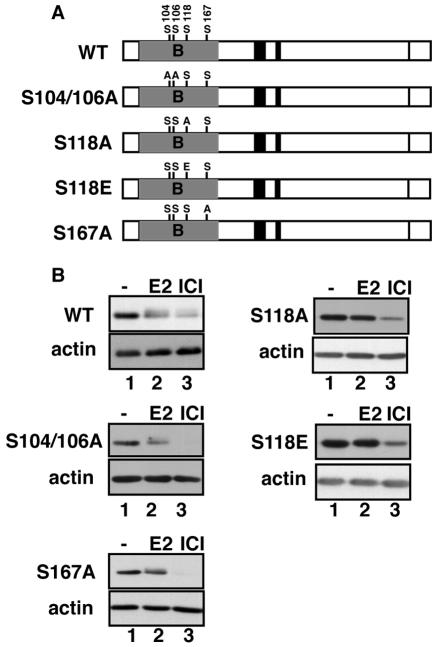

S118 is an essential determinant of E2-induced ERα degradation.

Next, we focused on previously identified functional amino acids in the B domain, including serine residues 104/106, 118, and 167. The major sites of E2-induced phosphorylation are S104/106 and S118 (3, 25). S118 can also serve as a phosphoacceptor site for mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways (22). Phosphorylation of S167, which might impact the stability of the association of ERα with DNA (8), is not induced by E2 (25) but has been shown to be stimulated by signaling cascades that activate AKT and RSK kinases (7, 20). Stable HEK293 cell lines were generated expressing S118A, S104/106A, and S167A mutant receptors, as shown in Fig. 3A, and tested for susceptibility to ligand-induced receptor degradation as before (Fig. 3B). Examination of relative ERα levels following E2 and ICI treatment by Western blotting shows that S104/106A-ERα and S167A-ERα were degraded in response to E2 and ICI similar to wild-type ERα. However, the S118A- ERα mutant was protected from estrogen-induced degradation. Earlier studies had demonstrated that with replacement of S118 with glutamic acid, a phosphomimetic amino acid (S118E) could substitute for phosphorylated S118-ERα in transcriptional assays (3). Thus, we generated stable cell lines expressing S118E-ERα. Surprisingly, when stable transformants expressing S118E were subjected to ligand treatment, this mutant was also resistant to E2-induced degradation (Fig. 3B). However, like S118A-ERα, S118E-ERα remained susceptible to degradation induced by ICI.

FIG. 3.

(A) Schematic illustration of serine residues in the ERα B domain and the corresponding serine-to-alanine mutants. Stable HEK293 cell lines were generated that express the WT or S104/106A, S167A, S118A, and S118E ERα mutants. (B) Shown are representative Western blots on whole-cell lysates obtained following a 4-h treatment with vehicle (lane 1), 10 nM E2 (lane 2), or 10 nM ICI (lane 3). Blots were probed with antibodies specific for ERα or actin.

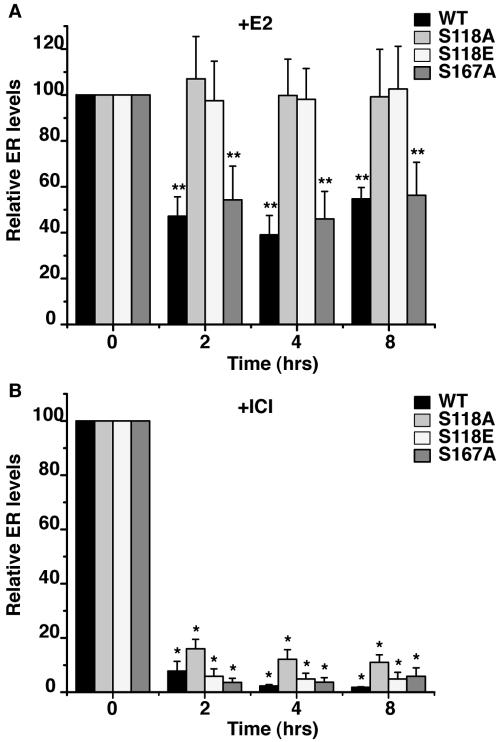

Western blot analysis was then performed to quantify changes in steady-state ERα levels following ligand treatment over time (Fig. 4). Cell clones expressing ERα variants were treated with either E2 or ICI for 2, 4, and 8 h. Shown in Fig. 4A, E2 treatment resulted in a significant decrease in ERα protein of the WT and S167A receptors within 2 h of exposure, which was maintained over the entire length of the experiment. However, receptor levels were unchanged by E2 treatment in cells expressing S118A and S118E. ICI treatment dramatically reduced the level of all variants of ERα tested (Fig. 4B). Although the degradation of S118 mutants was modestly impaired relative to the wild type, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 4B). These results are consistent with previous studies that indicated that the mechanisms governing E2- and ICI-induced degradation may be distinct (53). Thus, a single amino acid can distinguish both E2- and ICI-mediated ERα degradation and transcriptional activity (see below).

FIG. 4.

Stable cell lines expressing the WT or S118A, S118E, and S167A mutants were treated with 10 nM E2 or 10 nM ICI for the indicated number of hours. Western blots were performed on whole-cell lysates with antibody directed against ERα. Band intensity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. ERα levels are shown as a percentage of those at t = 0. Data are shown as the mean ERα level ± standard error of the mean based on a minimum of three independent trials and are expressed as the relative ERα levels in the presence of E2 (A) or ICI (B). Statistical differences were determined by Student's t test analysis (**, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.001).

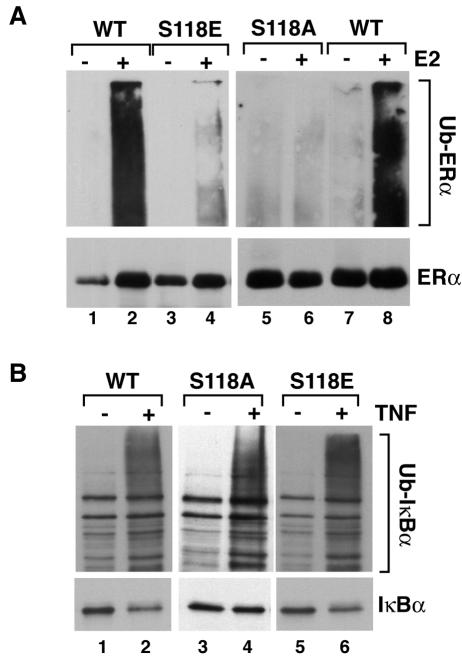

To identify the defect which stabilizes S118 mutants and to further confirm the involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in E2-inducible ERα protein downregulation in HEK293 cells, the ubiquitination statuses of the WT and serine mutants were compared (Fig. 5A). Stable cell lines were pretreated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, followed by treatment with EtOH or E2 for 4 h to allow accumulation of ubiquitylated intermediates. Cell lysates were boiled immediately at harvest in lysis solution containing 1% SDS to maximize preservation of ubiquitylated ERα species. ERα was then immunoprecipitated, and Western blots were performed for ubiquitin. Wild-type ERα was strongly ubiquitylated in response to hormone treatment in accordance with previous demonstrations in MCF-7 cells (53). The ubiquitylation of S118E-ERα was severely reduced, although there was a modest increase following treatment. Ubiquitylation of S118A-ERα was more severely compromised than S118E-ERα. TNF-inducible ubiquitylation of IkBα confirmed that the individual clones expressing the S118-ERα mutants did not have a general defect in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that the stability of S118A- and S118E- ERα is due to a specific defect in the ubiquitination pathway that targets ERα to the proteasome.

FIG. 5.

(A) Stable cell lines expressing the WT or S118A-ERα (S118A) and S118E-ERα (S118E) mutants were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 30 min followed by a 4-h treatment with ethanol (−) or 10 nM E2 (+). Ubiquitination status of ERα was determined by immunoprecipitation of ERα from whole-cell lysates, followed by Western analysis for ubiquitin (Ub), as described in Materials and Methods. The lower panel shows the blots reprobed with anti-ERα antibody. (B) Shown is a representative Western analysis for IκBα in the different stable ERα cell lines pretreated with 10 μM MG132 and treated for 10 min with (+) or without (−) 10 mg/ml TNF. The top panel shows a long exposure revealing ubiquitinated IκBα. The bottom panel shows unmodified IκBα in a shorter exposure of the same blot.

Stable S118A and S118E mutants have opposite effects on ERα-mediated induction of endogenous target gene expression.

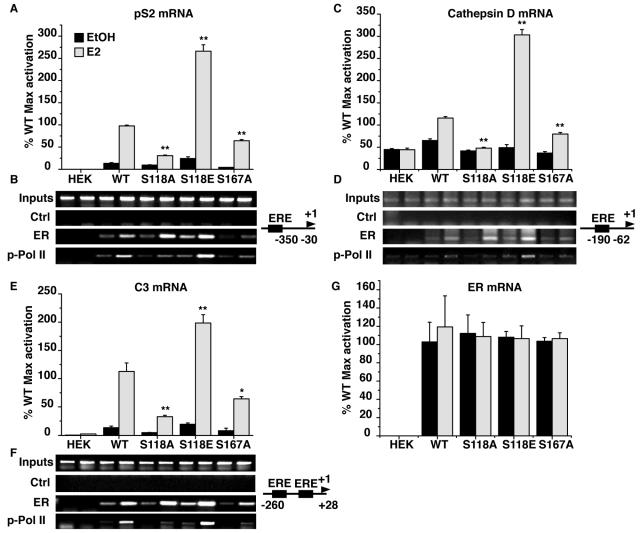

Earlier studies demonstrated that S118A and S118E ERα mutants have opposing effects on ligand-induced receptor transcriptional activation of reporter genes (3, 12, 25). Our findings, thus far, demonstrate that both mutants are resistant to E2-induced degradation. This evidence suggested that the stability of receptor protein and induction of gene expression may be independently regulated. To test whether estrogenic regulation of ERα transactivation was similarly affected by S118 mutation in our model, we capitalized on the finding that stable expression of ERα in HEK293 cells is sufficient to permit induction of endogenous, estrogen-responsive target genes (Fig. 6). Quantitative PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from stable cell lines expressing WT, S118A, S118E, and S167A ERα variants treated with either EtOH or E2 using primers specific for pS2, cathepsin D (CATSD), and complement 3 (C3) (Fig. 6A, C, and E). Importantly, compared to wild-type ERα, S118A-ERα showed diminished transcriptional activity, while S118E showed enhanced gene activation. S167A-ERα also showed reduced transactivation capacity. When calculated as fold induction over vehicle-treated controls, estrogen induced a 7.4 ± 0.47-fold increase in pS2 expression in WT ERα-expressing cells, while similar treatment of S118A-ERα- and S118E-ERα-expressing cells resulted in 3.2 ± 0.24- and 11.1 ± 1.28-fold inductions, respectively (Fig. 6A). Estrogen induced a 15 ± 0.7-fold induction in pS2 gene expression in S167A-ERα-expressing cells, but this increase is largely due to the decreased basal activity of the S167A mutation, and the overall magnitude of transactivation was significantly diminished by 34.9% ± 1.7% compared to WT. A similar pattern of gene regulation was observed for the CATSD and C3 genes (Fig. 6C and 6D). The level of ERα expression was equivalent in all four cell lines (Fig. 6G). Though the S118E mutant is stable like S118A, its transcriptional properties are clearly opposite. ChIP experiments assessing the recruitment of ER proteins and phosphorylated RNA polymerase II (p-Pol II) on the three genes' promoters confirmed these results (Fig. 6B, D, and F). In accordance with earlier studies (40), ERα is bound to the promoters in the absence of E2, with the S118E mutant displaying a greater level of promoter occupancy. E2 treatment resulted in an increase in promoter occupancy, but levels varied among the receptor subtypes. S118A-ERα and S118E-ERα displayed increased promoter occupancy relative to wild-type and S167A receptors, correlating with their respective stability upon E2 exposure. Promoter occupancy by p-Pol II indicated a direct correlation between the recruitment of Pol II transcription machinery and the induction of gene transcription. Thus, these data indicate that the stability of ERα protein is separable from the ability to activate transcription of endogenous target genes under our experimental settings.

FIG. 6.

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods on total RNA isolated from stable HEK293 cells expressing the WT or S118A, S118E, and S167A mutant ERα treated with either EtOH or 10 nM E2. Estrogen induction of endogenous pS2 (A), cathepsin D (C), C3 (E), and ERα (G) mRNA was assessed. Values were normalized against the relative expression of the PO gene and are expressed as a percentage of the maximal induction achieved by E2 in WT ERα cells from the first experiment. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments, except for the ERα experiment, which was performed twice. Statistical differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance and Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01), relative to the E2-treated WT sample. Parallel ChIP experiments were performed on chromatin prepared from HEK293 cells expressing the different ERα proteins treated as described in Materials and Methods. These experiments followed the recruitment of ERα and p-Pol II on the endogenous pS2 (B), cathepsin D (D), and C3 (F) promoters, with a control (Ctrl) ChIP using nonspecific immunoglobulin G. Also shown are schemes depicting the structures of the three promoters, with the PCR-amplified regions highlighted.

ERα stability correlates with E3 ligase recruitment but not that of coactivators and transcriptional machinery to a target gene promoter.

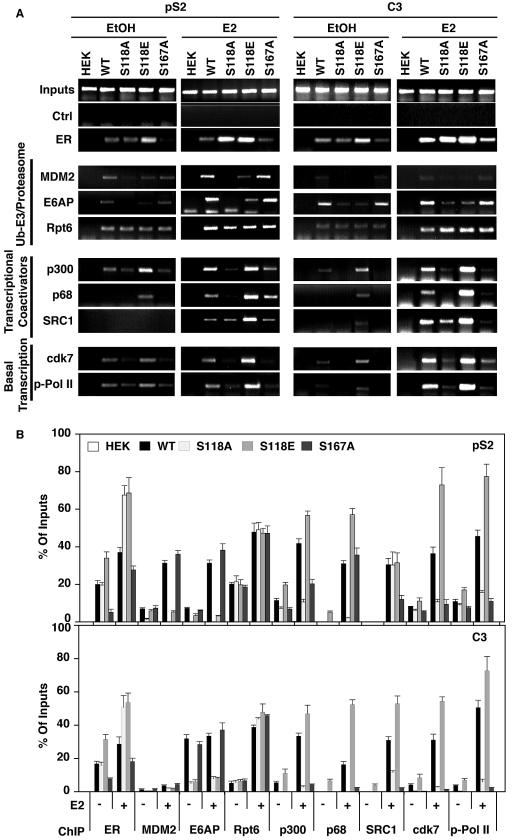

The current model suggests that ubiquitin E3 ligases and coactivators are coordinately recruited by ERα to target genes and this E3 recruitment then regulates both ERα degradation and transcription. To test whether this sequence of events is occurring on the endogenous pS2 and C3 promoters, targeted ChIP analysis was conducted to examine the proteins recruited to the pS2 promoter along with ERα mutants in the absence and presence of E2 (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, like ERα, the ubiquitin E3 ligases, E6-AP and MDM2, and the Rpt6 subunit of the 19S proteasome were present on the pS2 promoter in the absence of ligand. However, E2 treatment induced greater ligase occupancy of promoters in cells expressing WT and S167A, but there was no recruitment to the pS2 promoter by S118A-ERα. The recruitment of these ligases was also diminished on promoters occupied by S118E relative to WT and S167A, consistent with the weak induction of ubiquitination observed on this mutant in response to E2. However, the Rpt6 subunit was equivalently recruited to the promoter regardless of the ERα mutant present. Analysis of the C3 promoter showed a similar correlative pattern; however, unlike the pS2 promoter, MDM2 showed ligand-dependent increases in promoter occupancy in the presence of S118A and S118E ERα mutants, although the overall levels of recruitment were greatly reduced relative to those of WT and S167A-ERα cell lines (Fig. 7B and Table 1). These results indicate that S118 plays a critical role in ubiquitination and degradation of ERα through the recruitment of E3 ligases to the promoter. The APIS complex was recruited to the promoter independent of E3 recruitment and ubiquitination status of ERα. Furthermore, the pattern of promoter occupancy revealed by coactivators (p300, p68, and SRC1) did not mirror the ERα mutant stability properties but rather showed a good correlation with relative transcriptional activity (Fig. 6A and C). Finally, promoter occupancy by p-PolII and cdk7 kinase, a component of TFIIH, illustrated, again, the correlation between the recruitment of these basal transcriptional components and the induction of gene transcription. A summary of the quantitative assessment of these results by quantitative PCR is shown in Fig. 7B. Collectively, our findings indicate that ERα targeted for degradation correlates with recruitment of E3 ligases to the promoter, while ERα can independently assemble coactivators and components of the basal transcriptional machinery whether stable or not.

FIG.7.

Occupancy of pS2 and human complement component 3 (hC3) promoters by ERα, ubiquitination/proteasome components (E6AP, MDM2, Rpt6), coactivators (p300, p68, SRC1), and basal transcriptional machinery (p-Pol II and cdk7) was assessed by ChIP assays. Stable HEK293 cells expressing the indicated ERα variant were treated with 10 nM E2 or EtOH, following synchronization with α-amanitin. Recovered DNA was amplified with primers to the pS2 and C3 promoters described in Materials and Methods and visualized by ethidium bromide staining in agarose gels (A). (B) Shown are the quantification of these ChIP assays by quantitative PCR, as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 1.

Degradation transactivation, and promoter occupancy of ERα mutants, proteasome components, and transcriptional cofactors in stable HEK293 cell lines on pS2 and C3 endogenous target genesa

| ERα | E2 | Degradation (% protein) | Transactivation activity (% WT) | Promoter occupancy (relative ChIP value [% input])

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ub-E3/proteasome

|

Coactivator

|

Basal transcription

|

||||||||||

| ER | E6AP | MDM2 | Rpt6 | p300 | p68 | SRC1 | cdk7 | p-PoIII | ||||

| pS2 | ||||||||||||

| WT | − | 19.9 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 20.1 | 11.4 | 0 | 0 | 8.2 | 10.8 | ||

| + | 47.7 | 100 | 36.9 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 47.8 | 41.7 | 30.9 | 30.4 | 36.3 | 45.5 | |

| S118A | − | 19.6 | 0 | 1.5 | 21.4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 9.1 | ||

| + | 99.8 | 31.3 | 67.5 | 0 | 0 | 49.1 | 10.6 | 2.2 | 30.2 | 10.7 | 15.7 | |

| S118E | − | 33.9 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 5.2 | 0 | 11.1 | 17.0 | ||

| + | 98.1 | 272.2 | 68.6 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 47.2 | 56.8 | 57.0 | 31.4 | 72.9 | 77.4 | |

| S167A | − | 5.1 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 18.6 | 6.8 | 0 | 0 | 5.6 | 7.5 | ||

| + | 42.0 | 65.7 | 27.7 | 38.2 | 36.0 | 47.2 | 20.2 | 35.6 | 12.0 | 9.4 | 10.9 | |

| C3 | ||||||||||||

| WT | − | 16.8 | 31.9 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 | 3.9 | ||

| + | 47.7 | 100 | 28.7 | 33.5 | 3.7 | 38.8 | 33.4 | 16.3 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 50.6 | |

| S118A | − | 15.9 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | ||

| + | 99.8 | 31.8 | 50.7 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 43.8 | 2.9 | 0 | 11.7 | 2.7 | 5.8 | |

| S118E | − | 31.5 | 6.0 | 0.3 | 6.3 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 8.4 | 6.9 | ||

| + | 98.1 | 174.9 | 53.6 | 8.0 | 1.8 | 47.8 | 46.9 | 52.5 | 52.9 | 54.4 | 72.7 | |

| S167A | − | 7.9 | 28.5 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | ||

| + | 42.0 | 50.6 | 18.2 | 37.2 | 4.5 | 45.9 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 2.3 | |

DISCUSSION

In the current model of receptor mediated transcription, activation of ERα leads to the assembly of a multicomponent macromolecular complex on the DNA which modifies chromatin and recruits Pol II to initiate transcription. Kinetic analysis, using both fluorescence-based cell microscopy and ChIP, has shown this to be a highly dynamic process in which the complex association with promoters is transient and occurs in oscillatory periods (30, 41, 44). Components of the proteasome are recruited to ERα-induced complexes with timing coordinated with disengagement of the receptor with DNA. Thus, it has been postulated that proteasome-mediated degradation of receptor may have an active role in the disassembly of receptor complexes and modulate its subsequent transcriptional activation potential. Our results indicate that there can be a mechanistic separation of ERα proteolysis from its transcriptional activity. This is evidenced by the identification of four ERα mutants with various susceptibilities to E2-induced degradation with unmatched transactivation potentials. First, ΔB-ERα is stable but transcriptionally competent. Second, S118E-ERα escapes degradation but can induce levels of gene expression greater than wild type. Third, S167A-ERα is actively degraded but has diminished transactivation function. Finally, S118A-ERα mutant exhibits an intermediate phenotype in that it is stable like S118E-ERα but is less transcriptionally active, like S167A-ERα. The uncoupling of ERα transcription and proteolysis was probed further by examining select proteins that occupy the pS2 and C3 promoters along with ERα variants. The choice of protein partners tested was based on their potential involvement in either proteolysis (E3 ligases and proteasome subunits) or transcription (coactivators and basal transcription machinery). We found that the recruitment of proteins examined depended on the presence of ERα and was modulated by the addition of ligand, which is consistent with the model that ERα nucleates the macromolecular complex bound to estrogen-responsive promoters. The stability of ERα is inversely related to the occupancy of E3 ligases, while transcriptional activity is correlated with the recruitment of coactivators (SRC1, p300, and p68) and components of the basal transcriptional machinery (p-Pol II and cdk7 subunit of TFIIH). Given the lack of correlation between the stability of the receptor and its transcriptional activity (data summarized in Table 1), these results strongly argue against a direct requirement for ERα proteolysis in receptor transactivation function.

While estrogen-induced ERα degradation is not necessary for active transcription, the 26S proteasome could control receptor-mediated transcription by other means. Proteasome inhibitor studies indicate that blockade of proteasome function inhibits androgen receptor (AR) and ERα transcriptional activity (21) but enhances the activity of glucocorticoid receptor (50). Inhibitors of proteasome activity have also been shown to prevent recruitment of Pol II to promoter elements bound by ERα (41). ChIP analysis in Fig. 6 shows that the Rpt6 subunit of the 19S cap of the proteasome was recruited to active transcriptional complexes irrespective of the susceptibility of ERα to proteolysis. Moreover, multiple components of the receptor transcriptional complex, in addition to ERα, have been shown to be targets for proteasome-mediated degradation. It is thus possible that recruitment of the proteasome and subsequent degradation of those substrates may directly impact transcription in certain circumstances. An alternative possibility is that the 19S cap may play a role in ERα-mediated transcription not associated with receptor proteolysis. In support of this notion, Johnston and colleagues have shown a 19S subunit is involved in transcriptional elongation independent of proteolysis (16, 17). It is therefore intriguing to note that in the examination of the order of recruitment of proteins to ERα-occupied promoters, Rpt6 and elongation factors are brought to the promoter at the same time (30).

Multiple structural domains are involved in the control of inducible destruction of ERα protein. In Fig. 1, we show that the disruption of any domain, with the exception of the A domain, has an impact on the ligand-induced degradation of the mutant protein in HEK293 cells. The B domain is specifically required for estrogen-induced proteolysis. Combined with other studies showing a requirement for the ligand-binding domain and AF-2 (27, 49), we interpret these results to reflect the important regulatory role that the structural integrity of ERα plays in targeting receptor to proteasomes. Studies performed in T47D breast cancer cell lines found that estrogen-induced degradation was preserved despite deletion of the A/B, D, and the E/F domains (54). This suggests the possibility that cell-specific processes are also regulating the mechanisms involved in the degradation of ERα. However, another intriguing possibility arises from the fact that T47D cells express endogenous wild-type receptor. Thus, overexpression of a mutant in the background of endogenous receptor could result in heterodimers between wild-type and mutant ERα proteins. The susceptibility of wild-type ERα to degradation may dominantly control the degradation of a stable mutant partner, similar to what has been described for retinoid X receptor heterodimers (38).

The results presented in this study identify a novel function of S118 residue within the AF-1 region of ERα as a critical residue that plays dual but separate roles in regulating ERα proteolysis and transcription. Our results are consistent with previous studies that indicate that the charge modification associated with ligand-induced phosphorylation impacts the efficiency of ERα-regulated transcription (3, 9, 25). It has been demonstrated previously that the phosphorylation status of ERα at S118 impacts the efficiency of ligand-induced transcription in a cell-type- and promoter-specific manner (3, 22). Overexpression of the kinase components of TFIIH, cdk7, and MAT1, attributed to phosphorylation of S118, leads to heightened induction of reporter gene expression; a result also observed with mutation of S118E-ERα (9). Here, we analyzed endogenous gene induction and show that mutations that mimic the charge modification of phosphorylation indeed enhance ligand-induced ERα transcriptional function in the context of a chromatin environment, consistent with previous studies. Moreover, comparison of complexes bound to promoters with S118A or -E shows that the differences in transactivation exhibited by these mutants are reflected in different levels of occupancy of coactivators and transcriptional machinery to the promoter. These results are consistent with the notion that, in the context of transcription, S118 phosphorylation regulates transcriptional efficiency through the differential recruitment of coactivators and transcriptional machinery to estrogen-responsive promoters. However, mutations which exhibit opposing phenotypes with respect to ERα phosphorylation and transcriptional properties result in both a disruption of regulated ubiquitination and degradation of ERα. These data suggest that S118 is a critical residue for both the regulation of transcription and proteolysis, yet it represents a point of divergence where its posttranslational modification by phosphorylation contributes to transcription while a separate property is essential for ERα entry into the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. It is not clear how S118 contributes to proteolysis, but experiments are under way to try to identify the mechanism by which this residue regulates receptor stability.

Analysis of ERα proteolysis in relation to ChIP data presented in Fig. 7 indicates that there is a correlation between the stability of ERα protein and the recruitment of ubiquitin ligases to a promoter. Stenoien et al. have previously demonstrated that E2 induces the formation of ERα-containing nuclear foci which colocalize with the 26S proteasome but are not associated with active transcriptional complexes. In addition, it was shown that the ERα within these foci fractionates with nuclear matrix (48). Based on the combined data (refer also to Table 1), we hypothesize that E2 can induce proteolysis of at least two ERα populations: those receptors that recruit ubiquitin ligases as part of a transcriptional complex on promoters and those that are independently associated with nuclear matrix. The latter population could include nonfunctional receptors that might have concluded a transcriptional cycle, as suggested in the original model (41), but also might include receptors that never engaged in the transcription process.

In conclusion, we propose that the regulation of estrogen-induced proteolysis is mediated through the coordinate actions of the two ERα transactivation domains that facilitate recognition of receptor by ubiquitin ligases. S118 is a central player in this regulation. Importantly, its regulatory role in proteolysis is distinct from that contributing to transcriptional efficiency. This represents a previously unrecognized function of the N-terminal B domain and S118, wherein they contribute to the targeting of ERα complexes to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and independently, through posttranslational modification by phosphorylation, facilitate recruitment of receptor complexes that form active transcriptional units. The addition of a second required structural element in the ERα N terminus, which is physically separated from the C-terminal region involved in both transcription and proteolysis, provides a mechanism by which the destruction of ERα can be disengaged from its transcriptional function.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pierre Chambon and Benita Katzenellenbogen for their generous gift of ER constructs. We are also grateful to F. Fuller-Pace for antibodies to p68. Lastly, we appreciate the insightful comments we received from Shigeki Miyamoto, Fern Murdoch, Mike Fritsch, and Jack Gorski throughout the completion of these studies.

This work was funded by NIH grant DK64034 to E.T.A., CNRS, Université de Rennes I, Rennes Métropole, and grants from the ARC and Ligue contre le Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alarid, E. T., N. Bakopoulos, and N. Solodin. 1999. Proteasome-mediated proteolysis of estrogen receptor: a novel component in autologous down-regulation. Mol. Endocrinol. 13:1522-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarid, E. T., M. T. Preisler-Mashek, and N. M. Solodin. 2003. Thyroid hormone is an inhibitor of estrogen-induced degradation of estrogen receptor-α protein: estrogen dependent proteolysis is not essential for receptor transactivation function in the pituitary. Endocrinology 144:3469-3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali, S., D. Metzger, J.-M. Bornert, and P. Chambon. 1993. Modulation of transcriptional activation by ligand dependent phosphorylation of the human oestrogen receptor A/B region. EMBO J. 12:1153-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borras, M., L. Hardy, F. Lempereur, A. H. El Khissiin, N. Legros, R. Gol-Winkler, and G. Leclercq. 1994. Estradiol-induced down-regulation of estrogen receptor. Effect of various modulators of protein synthesis and expression. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48:325-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, A. M. C., J.-M. Jeltsch, M. Roberts, and P. Chambon. 1984. Activation of pS2 gene transcription is a primary response to estrogen in the human breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:6344-6348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brzozowski, A. M., A. C. W. Pike, Z. Dauter, R. E. Hubbard, T. Bonn, O. Engström, L. Öhman, G. L. Greene, J.-Å. Gustafsson, and M. Carlquist. 1997. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature 389:753-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, R. A., P. Bhat-Nakshatri, N. M. Patel, D. Constantinidou, S. Ali, and H. Nakshatri. 2001. Phophatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT-mediated activation of estrogen receptor α. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9817-9824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castano, E., D. P. Vorojeikina, and A. C. Notides. 1997. Phosphorylation of serine-167 on the human oestrogen receptor is important for oestrogen response element binding and transcriptional activation. Biochem. J. 326:149-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, D., T. Riedl, E. Washbrook, P. E. Pace, R. C. Coombes, J.-M. Egly, and S. Ali. 2000. Activation of estrogen receptor α by S118 phosphorylation involves a ligand-dependent interaction with TFIIH and participation of cdk7. Mol. Cell 6:127-137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conaway, R. C., C. S. Brower, and J. W. Conaway. 2002. Emerging roles of ubiquitin in transcription regulation. Science 296:1254-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dace, A., L. Zhao, K. S. Park, T. Furuno, N. Takamura, M. Nakanishi, B. L. West, J. A. Hanover, and S. Cheng. 2000. Hormone binding induce rapid proteasome-mediated degradation of thyroid hormone receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8985-8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutertre, M., and C. L. Smith. 2003. Ligand-independent interactions of p160/steroid receptor coactivators and CREB-binding protein (CBP) with estrogen receptor-α: regulation by phosphorylation sites in the A/B region depends on other receptor domains. Mol. Endocrinol. 17:1296-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Khissiin, A., and G. Leclercq. 1999. Implication of proteasome in estrogen receptor degradation. FEBS Lett. 448:160-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Khissin, A., A. Cleeren, M. Borras, and G. LeClercq. 1997. Protein synthesis is not implicated in the ligand-dependent activation of estrogen receptor in MCF-7 cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 62:269-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan, M., H. Nakshatri, and K. P. Nephew. 2004. Inhibiting proteasomal proteolysis sustains estrogen receptor-α activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 18:2603-2615. (First published 29 July 2004; doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0164.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferdous, A., F. Gonzalez, L. Sun, T. Kodadek, and S. A. Johnston. 2001. The 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome is required for efficient transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 7:981-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferdous, A., T. Kodadek, and S. A. Johnston. 2002. A nonproteolytic function of the 19S regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome is required for efficient activated transcription by human RNA polymerase II. Biochemistry 41:12798-12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flouriot, G., H. Brand, S. Denger, R. Metivier, M. Kos, G. Reid, V. Sonntag-Buck, and F. Gannon. 2000. Identification of a new isoform of the human estrogen receptor-alpha (hER-α) that is encoded by distinct transcripts and that is able to repress hER-α activation function 1. EMBO J. 19:4688-4700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauser, S., G. Adelmant, P. Sarraf, H. M. Wright, E. Mueller, and B. M. Spiegelman. 2000. Degradation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is linked to ligand-dependent activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18527-18533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joel, P. B., J. Smith, T. W. Sturgill, T. L. Fisher, J. Blenis, and D. A. Lannagin. 1998. pp90rsk1 regulates estrogen receptor-mediated transcription through phosphorylation of Ser-167. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1978-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang, Z., A. Pirskanen, O. A. Janne, and J. J. Palvimo. 2002. Involvement of proteasome in the dynamic assembly of the androgen receptor transcription complex. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48366-48371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato, S., H. Endoh, Y. Masuhiro, T. Kitamoto, S. Uchiyama, H. Sasaki, S. Masushige, Y. Gotoh, E. Nishida, H. Kawashima, D. Metzger, and P. Chambon. 1995. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science 270:1491-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar, V., S. Green, G. Stack, M. Berry, J.-R. Jin, and P. Chambon. 1987. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell 51:941-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange, C. A., T. Shen, and K. B. Horwitz. 2000. Phosphorylation of human progesterone receptors at serine-294 by mitogen-activated protein kinase signals their degradation by the 26S proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1032-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeGoff, P., M. M. Montano, D. J. Schodin, and B. S. Katzenellenbogen. 1994. Phosphorylation of the human estrogen receptor. Identification of hormone-regulated sites and examination of their influence on transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4458-4466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, H.-K., S. Altuwaijri, W.-J. Lin, P.-Y. Kan, L. L. Collins, and C. Chang. 2002. Proteasome activity is required for androgen receptor transcriptional activity via regulation of androgen receptor nuclear translocation and interaction with coregulators in prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:36570-36576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lonard, D. M., Z. Nawaz, C. L. Smith, and B. W. O'Malley. 2000. The 26S proteasome is required for estrogen receptor-α and coactivator turnover and for efficient estrogen receptor-α transactivation. Mol. Cell 5:939-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuyama, H., and Y. Hiramatsu. 2004. Involvement of suppressor for Gal1 in ubiquitin/proteasome mediated degradation of estrogen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 26:12020-12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuyama, H., and P. N. MacDonald. 1998. Proteasome-mediated degradation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and a putative role for SUG1 interaction with the AF-2 domain of VDR. J. Cell. Biochem. 71:429-440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mètivier, R., G. Penot, M. R. Hübner, G. Reid, H. Brand, M. Koš, and F. Gannon. 2003. Estrogen receptor-α directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell 115:751-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mètivier, R., A. Stark, G. Flouriot, M. R. Hübner, H. Brand, G. Penot, D. Manu, S. Denger, G. Reid, M. Koš, R. B. Russell, O. Kah, F. Pakdel, and F. Gannon. 2002. A dynamic structural model for estrogen receptor-α activation by ligands, emphasizing the role of interactions between distant A and E domains. Mol. Cell 10:1019-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyamoto, S., B. J. Seufzer, and S. Shumway. 1998. Novel IκBα proteolytic pathway in WEHI231 immature B cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:19-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molinari, E., M. Gilman, and S. Natesan. 1999. Proteasome-mediated degradation of transcriptional activators correlates with activation domain potency in vivo. EMBO J. 18:6439-6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muratani, M., and W. P. Tansey. 2003. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat. Rev. 4:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nawaz, Z., D. M. Lonard, C. L. Smith, E. Lev-Lohman, S. Y. Tsai, M.-J. Tsai, and B. W. O'Malley. 1999. The Angelman syndrome-associated protein, E6-AP, is a coactivator for the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1182-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nawaz, Z., D. M. Lonard, A. P. Dennis, C. L. Smith, and B. W. O'Malley. 1999. Proteasome-dependent degradation of the human estrogen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1858-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nomura, Y., T. Nagaya, Y. Hayashi, F. Kambe, and H. Seo. 1999. 9-cis-retinoic acid decreases the level of its cognate receptor, retinoic X receptor, through acceleration of the turnover. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260:729-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osburn, D. L., G. Shao, H. M. Seidel, and I. G. Schulman. 2001. Ligand-dependent degradation of retinoid X receptors does not require transcriptional activity or coactivator interactions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4909-4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pickart, C. M. 2001. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:503-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preisler-Mashek, M. T., N. Solodin, B. L. Stark, M. K. Tyriver, and E. T. Alarid. 2002. Ligand-specific regulation of proteasome-mediated proteolysis of estrogen receptor-α. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol Metab. 282:E891-E898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid, G., M. R. Hubner, R. Metivier, B. Heike, S. Denger, D. Manu, J. Beaudouin, J. Ellenberg, and F. Gannon. 2003. Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERα on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Mol. Cell 11:695-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin, D. M., O. Coux, I. Wefes, C. Hengartner, R. A. Young, A. L. Goldberg, and D. Finley. 1996. Identification of the gal4 suppressor Sug1 as a subunit of the yeast 26S proteasome. Nature 379:655-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salghetti, S. E., M. Muratani, H. Wijnen, B. Futcher, and W. P. Tansey. 2000. Functional overlap of sequences that activate transcription and signal ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3118-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shang, Y., X. Hu, J. DiRenzo, M. A. Lazar, and M. Brown. 2000. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103:843-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao, W., E. K. Keeton, D. P. McDonnell, and M. Brown. 2004. Coactivator AIB1 links estrogen receptor transcriptional activity and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:11599-11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shull, J. D., J. H. Walent, and J. Gorski. 1987. Estradiol stimulates prolactin gene transcription in primary cultures of rat anterior pituitary cells. J. Steroid Biochem. 26:451-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soulez, M., and M. G. Parker. 2001. Identification of novel oestrogen receptor target genes in human ZR175-1 breast cancer cells by expression profiling. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 27:259-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stenoien, D. L., M. G. Mancini, K. Patel, E. A. Allegretto, C. L. Smith, and M. A. Mancini. 2000. Subnuclear trafficking of estrogen receptor-α and steroid receptor coactivator-1. Mol. Endocrinol. 14:518-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tateishi, Y., Y. Kawabe, T. Chiba, S. Murata, K. Ichikawa, A. Murayama, K. Tanaka, T. Baba, S. Kato, and J. Yanagisawa. 2004. Ligand-dependent switching of ubiquitin-proteasome pathways for estrogen receptor. EMBO J. 23:4813-4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace, A. D., and J. A. Cidlowski. 2001. Proteasome-mediated glucocorticoid receptor degradation restricts transcriptional signaling by glucocorticoids. J. Biol. Chem. 276:42714-42721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watters, J. J., J. S. Campbell, J. J. Cunningham, E. G. Krebs, and D. M. Dorsa. 1997. Rapid membrane effects of steroids in neuroblastoma cells: effects of estrogen on mitogen activated protein kinase signalling cascade and c-fos immediate early gene transcription. Endocrinology 138:4030-4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitesell, L., and P. Cook. 1996. Stable and specific binding of heat shock protein 90 by geldanamycin disrupts glucocorticoid receptor function in intact cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 10:705-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wijayaratne, A. L., and D. P. McDonnell. 2001. The human estrogen receptor-α is a ubiquitinated protein whose stability is affected differentially by agonists, antagonists and selective estrogen receptor modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35684-35692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wormke, M., M. Stoner, B. Saville, K. Walker, M. Abdelrahim, R. Burghardt, and S. Safe. 2003. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediates degradation of estrogen receptor α through activation of proteasomes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1843-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu, J., M. Gianni, E. Kopf, N. Honore, M. Chelbi-Alix, M. Koken, F. Quignon, C. Rochette-Egly, and H. de The. 1999. Retinoic acid induces proteasome-dependent degradation of retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) and oncogenic RARα fusion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14807-14812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]