Abstract

Aims

Although evaluation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is crucial for deciding the rate control strategy in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), real-time assessment of LVEF is limited in outpatient settings. We aimed to investigate the performance of artificial intelligence–based algorithms in predicting LV systolic dysfunction (LVSD) in patients with AF and rapid ventricular response (RVR).

Methods and results

This study is an external validation of a pre-existing deep learning algorithm based on residual neural network architecture. Data were obtained from a prospective cohort of AF with RVR at a single centre between 2018 and 2023. Primary outcome was the detection of LVSD, defined as a LVEF ≤ 40%, assessed using 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG). Secondary outcome involved predicting LVSD using 1-lead ECG (Lead I). Among 423 patients, 241 with available echocardiography data within 2 months were evaluated, of whom 54 (22.4%) were confirmed to have LVSD. Deep learning algorithm demonstrated fair performance in predicting LVSD [area under the curve (AUC) 0.78]. Negative predictive value for excluding LVSD was 0.88. Deep learning algorithm resulted competent performance in predicting LVSD compared with N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (AUC 0.78 vs. 0.70, P = 0.12). Predictive performance of the deep learning algorithm was lower in Lead I (AUC 0.68); however, negative predictive value remained consistent (0.88).

Conclusion

Deep learning algorithm demonstrated competent performance in predicting LVSD in patients with AF and RVR. In outpatient setting, use of artificial intelligence–based algorithm may facilitate prediction of LVSD and earlier choice of drug, enabling better symptom control in AF patients with RVR.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Deep learning, Left ventricular ejection fraction, Atrial fibrillation, Rate control

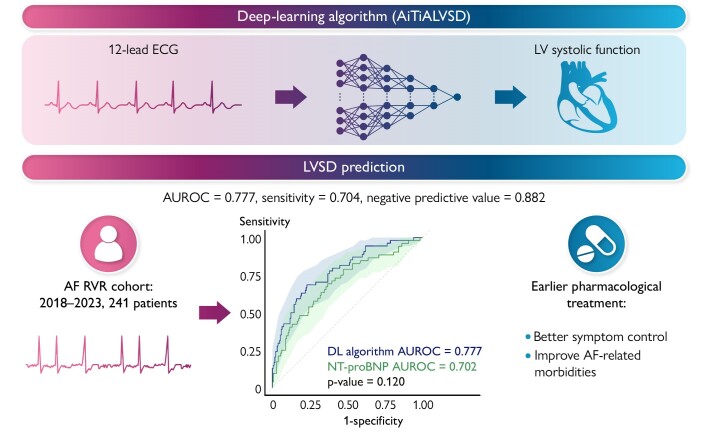

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

ECG, electrocardiography; LV, left ventricular; AF, atrial fibrillation; RVR, rapid ventricular response; LVSD; left ventricular systolic dysfunction; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most prevalent sustained cardiac arrhythmia in adults, exerting a significant burden on patients and healthcare system.1 Initial detection of AF prompts a comprehensive cardiovascular assessment for affected individuals.2 In the case of AF, echocardiographic evaluation is important for evaluating underlying substrate and guiding subsequent treatment decisions. The assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic function is mandatory within the standard diagnostic evaluation package for AF.1

Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response (RVR) contributes significantly to patient-related symptoms, healthcare utilization, and the development of heart failure.3 Effective rate control is an integral part of management in patients with AF and RVR, leading to improved AF-related symptoms and a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations.4 Accordingly, current guideline recommends that prompt evaluation of LV function should precede rate control and long-term rhythm control.1,5 However, conducting real-time assessments of LV function through transthoracic echocardiography in an outpatient, emergency, or primary care setting poses considerable challenges. Over the past two decades, there has been a substantial increase in the volume of transthoracic echocardiography in clinical practice.6 Moreover, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the supply–demand mismatch for routine outpatient echocardiography, resulting in waiting times exceeding 6 weeks.7

The use of 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) is recommended for all patients with AF, providing a simple and readily accessible tool in the outpatient or primary care setting.1 Predictive algorithms using deep learning techniques have demonstrated remarkable performance in various medical applications, particularly in image detection and clinical outcome prediction.8–10 Various ECG-based deep learning algorithms have been introduced to predict LV systolic function.11,12 To date, there was little evidence to utilize ECG-based deep learning algorithm in patients with AF, especially those in RVR. Thus, this study aimed to assess the efficacy of a deep learning algorithm in predicting LV systolic dysfunction (LVSD) among patients with AF and RVR and to investigate its feasibility in clinical practice.

Methods

Database

This is a validation study of a pre-existing deep learning algorithm that predicts LVSD from 12-lead ECG.12 External data were obtained from the established observational cohort of the AF RVR registry at the Korea University, Anam Hospital. The AF RVR registry was initially established to investigate the clinical outcomes of patients with AF experiencing RVR. Adult patients were prospectively enrolled in the registry between October 2018 and May 2023, if they met the study criteria of (i) being diagnosed with AF and (ii) having available 12-lead ECG records of AF or atrial flutter with a ventricular rate ≥ 100 b.p.m. Twelve-lead ECGs that were successfully converted to an analysable format (XML file) via central viewer server (MUSE, GE Healthcare) were included in the analysis. Exclusions from the analysis encompassed patients who (i) lacked a 12-lead ECG record for AF and RVR or had ECGs that were not converted to analysable format, (ii) were not examined using transthoracic echocardiography, or (iii) withdrew their informed consent. Additionally, patients who did not undergo echocardiography within 2 months of 12-lead ECG were excluded. The registry protocols adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea University Medicine, Anam Hospital, due to the retrospective nature of this study, and previous informed consent was obtained upon enrolment to the registry.

Outcome measurement and definition of variables

The primary outcome was the detection of LVSD, defined as a LV ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%, using data from the 12-lead ECG. The secondary outcome involved predicting LVSD using the 1-lead (Lead I) of the 12-lead ECG. The 12-lead ECG at the day of the registry enrolment was used for the analysis. If there were multiple ECGs at the same day (of enrolment), the initial ECG presented with AF and RVR was used. During transthoracic echocardiography, the LVEF was measured using the modified Simpson’s method. In patients with AF during echocardiography, LVEF was calculated from the average value of three consecutive beats.13 Only formal echocardiographic records were included in the analysis. N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) measured at the time of AF with RVR or the nearest value was collected.

Development of the deep learning algorithm

In 2019, Kwon et al.12 developed a model utilizing artificial intelligence for screening LVSD through the analysis of 12-lead ECG. In 2023, following additional clinical research and development, this algorithm-based software, known as AiTiALVSD version 1.00.00, obtained approval and clearance from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea, recognized as an artificial intelligence/machine learning–based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD).14–17 The AiTiALVSD artificial intelligence algorithm was developed using a residual neural network architecture and exclusively relies on digital signals with a frequency of 500 Hz from 12-lead raw ECG data as its input, without incorporating additional clinical variables. The output is an LVSD probability score, presented as a decimal ranging from 0 to 100, precise to the first decimal place. A defined probability score of 9.7 serves as the threshold distinguishing high and low risk, a parameter established to yield a performance level approaching 90% sensitivity. For Lead I analysis, the software’s artificial intelligence algorithm was adapted to use Lead I from a 12-lead ECG as input, maintaining the same output configuration as previously described. Further details about the development of deep learning algorithm are specified in the Supplementary material. The AiTiALVSD is not opened to the public as the algorithm is proprietary to the company (Medical AI Co., Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

The diagnostic efficacy of AiTiALVSD was assessed utilizing various metrics, including the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value (NPV). Each metric was reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for primary and secondary outcomes. The continuous LVSD probability score was employed for calculating AUROC and AUPRC, while other metrics utilized a predetermined cut-off of 9.7. N-terminal proBNP was used to predict LVSD, and the cut-off value to predict LVSD was calculated based on Youden index. Data underwent statistical analysis using appropriate tests, including the Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of the primary outcome. Statistical significance was ascertained at values of P < 0.05. Comprehensive analyses were conducted employing R software version 4.1.0 and Python 3.8.

Results

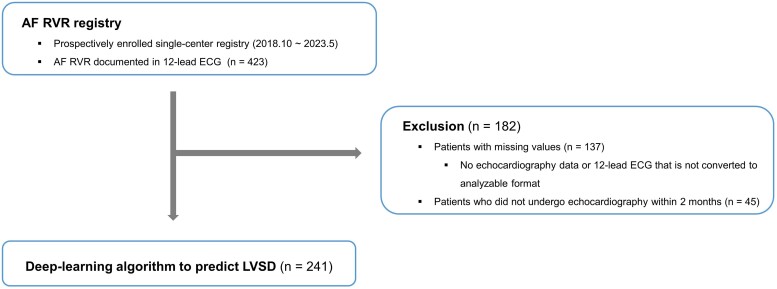

A total of 423 patients with AF and RVR were enrolled in the registry between October 2018 and May 2023 (Figure 1). Exclusions included patients (i) with missing echocardiography data or 12-lead ECG not converted to an analysable format (n = 137) and (ii) those who did not undergo echocardiography within 2 months (n = 45), resulting in the inclusion of 241 consecutive patients for analysis. The mean age of the patients was 65.4 ± 12.0 years, and 160 (66.4%) of them were male (Table 1). The baseline heart rate during RVR was 120.6 ± 15.6 b.p.m.. Ninety-two patients (38.2%) had paroxysmal AF, and 10 presented with atrial flutter (4.1%). In total, 183 (75.9%) of the 12-lead ECGs were performed in outpatient clinics, and 42 (38.2%) were performed in the emergency department. The mean duration from 12-lead ECG to echocardiography was 17.5 ± 15.9 days, and 181 (75.1%) of the patients had AF or atrial flutter during the echocardiographic assessment. The mean LVEF was 47.9 ± 10.8%, and the mean left atrial diameter was 44.2 ± 6.5 mm. Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed LVSD in 54 patients (22.4%). Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy or AF were the most common aetiologies of LVSD (74.1%; Supplementary material online, Table S1). Patients with LVSD more frequently maintained AF (or atrial flutter) during the echocardiographic assessment and exhibited significantly increased left atrial diameter and NT-proBNP.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the patient selection process. AF, atrial fibrillation; RVR, rapid ventricular response; ECG, electrocardiography; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study patients

| Total cohort | LVSD | No LVSD | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 241) | (n = 54) | (n = 187) | ||

| Age (years) | 65.4 ± 12.0 | 63.8 ± 13.1 | 65.8 ± 11.7 | 0.272 |

| Male sex | 160 (66.4) | 43 (79.6) | 117 (62.6) | 0.243 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.2 ± 3.7 | 25.4 ± 5.1 | 25.2 ± 3.3 | 0.752 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 120.6 ± 15.6 | 123.0 ± 16.8 | 120.0 ± 15.2 | 0.212 |

| Place during AF RVR | 0.906 | |||

| Outpatient clinic | 183 (75.9) | 37 (68.5) | 146 (78.1) | |

| Admission | 16 (6.6) | 5 (9.3) | 11 (5.9) | |

| Emergency department | 42 (17.4) | 12 (22.2) | 30 (16.0) | |

| Paroxysmal AF | 92 (38.2) | 18 (33.3) | 74 (39.6) | 0.952 |

| Atrial flutter | 10 (4.1) | 2 (3.7) | 8 (4.3) | 0.853 |

| Duration of AF (years) | 2.4 ± 3.9 | 2.3 ± 3.7 | 2.4 ± 4.0 | 0.872 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| Time to echocardiography (days) | 17.5 ± 15.9 | 16.8 ± 15.8 | 17.7 ± 15.9 | 0.719 |

| Rhythm during echocardiography | 0.008 | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 60 (24.9) | 3 (5.6) | 57 (30.5) | |

| AF or atrial flutter | 181 (75.1) | 51 (94.4) | 130 (69.5) | |

| Left ventricular diastolic dimension (mm) | 47.6 ± 6.3 | 51.4 ± 8.5 | 46.5 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular systolic dimension (mm) | 32.8 ± 7.5 | 40.3 ± 9.5 | 30.6 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Septal thickness (mm) | 10.2 ± 1.7 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 1.7 | 0.314 |

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) | 9.6 ± 1.4 | 9.7 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | 0.529 |

| Aorta thickness (mm) | 32.4 ± 4.4 | 32.0 ± 5.5 | 32.7 ± 4.0 | 0.418 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 44.2 ± 6.5 | 46.5 ± 6.5 | 43.6 ± 6.3 | 0.004 |

| Left atrial volume index (kg/m2) | 48.6 ± 19.4 | 51.9 ± 19.8 | 47.9 ± 19.4 | 0.494 |

| Left ventricular mass (g) | 168.7 ± 52.1 | 193.8 ± 70.0 | 161.5 ± 43.3 | 0.002 |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2) | 95.2 ± 24.7 | 106.7 ± 31.2 | 91.9 ± 21.4 | 0.002 |

| LVEF (%) | 48.0 ± 10.8 | 31.4 ± 7.1 | 52.8 ± 5.8 | <0.001 |

| E | 73.7 ± 21.5 | 75.7 ± 17.7 | 73.2 ± 22.4 | 0.506 |

| e′ | 7.3 ± 2.3 | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 2.3 | 0.011 |

| E/e′ | 11.3 ± 5.8 | 13.1 ± 6.2 | 10.8 ± 5.6 | 0.023 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (m/s) | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.020 |

| Estimated pulmonary artery pressure (mmHg) | 34.8 ± 7.8 | 34.6 ± 8.4 | 34.8 ± 7.7 | 0.874 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 0.789 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1493.3 ± 2235.1 | 2796.8 ± 3642.2 | 1120.8 ± 1437.1 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 122 (50.6) | 30 (55.6) | 92 (49.2) | 0.954 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (18.3) | 9 (16.7) | 35 (18.7) | 0.998 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 84 (34.9) | 14 (25.9) | 70 (37.4) | 0.641 |

| Thyroid disease | 36 (14.9) | 10 (18.5) | 26 (13.9) | 0.951 |

| Vascular disease | 18 (7.5) | 6 (11.1) | 12 (6.4) | 0.855 |

| Heart failure | 118 (49.0) | 53 (98.2) | 65 (34.8) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 29 (12.0) | 3 (5.6) | 26 (13.9) | 0.599 |

| Electrocardiography | ||||

| PR interval (ms) | 155.0 ± 32.0 | 151.7 ± 8.6 | 156.4 ± 38.7 | 0.843 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 91.6 ± 17.8 | 96.7 ± 19.5 | 90.2 ± 17.0 | 0.017 |

| QT interval (ms) | 324.6 ± 32.8 | 327.7 ± 37.1 | 323.7 ± 31.5 | 0.424 |

| QTc interval (ms) | 456.7 ± 41.8 | 464.6 ± 48.9 | 454.4 ± 39.4 | 0.117 |

| P-axis | 105.7 ± 93.4 | 157.5 ± 110.3 | 85.0 ± 82.9 | 0.201 |

| R-axis | 44.3 ± 54.3 | 53.0 ± 63.8 | 41.7 ± 51.2 | 0.180 |

| T-axis | 32.2 ± 57.9 | 47.4 ± 69.1 | 27.8 ± 53.7 | 0.028 |

| AiTiALVSD-12L score | 18.1 ± 23.7 | 37.9 ± 31.9 | 12.3 ± 16.9 | <0.001 |

| AiTiALVSD-1L score | 19.9 ± 18.4 | 30.3 ± 22.8 | 17.0 ± 15.8 | <0.001 |

LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; AF, atrial fibrillation; b.p.m., beats per minute; RVR, rapid ventricular response; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide.

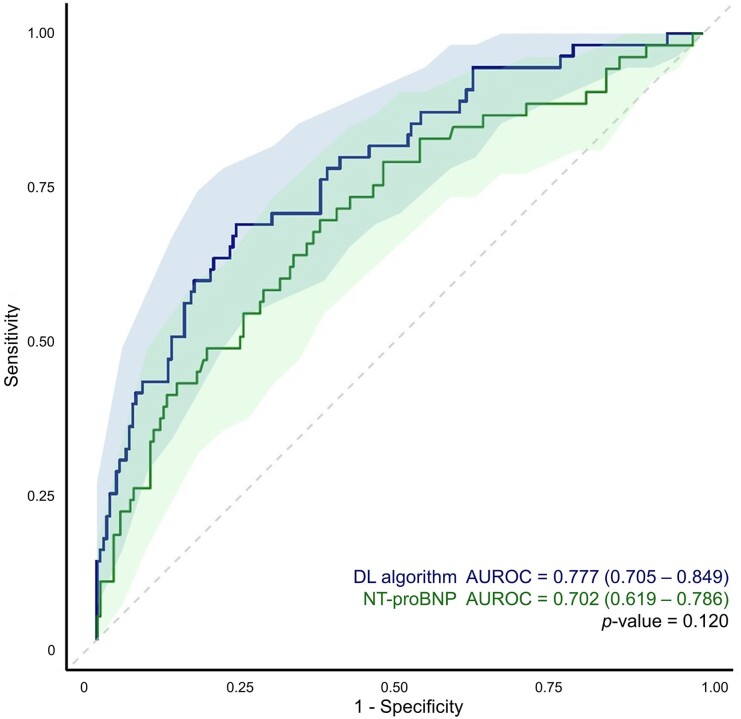

Model performance

The deep learning algorithm, using 12-lead ECG, demonstrated an AUROC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.71–0.85) for predicting LVSD (Table 2 and Figure 2). The NPV for excluding LVSD was 0.88 (95% CI 0.83–0.94). N-terminal proBNP was also utilized to predict LVSD, which resulted a cut-off value of 911.2 pg/mL. The deep learning algorithm revealed competent performance compared with NT-proBNP in predicting LVSD in patients with AF and RVR.

Table 2.

Model performance for evaluating primary outcome

| Deep learning algorithm | NT-proBNP | |

|---|---|---|

| AUROC (95% CI) | 0.777 (0.705–0.849) | 0.702 (0.619–0.786) |

| AUPRC (95% CI) | 0.321 (0.252–0.388) | 0.449 (0.340–0.564) |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 0.704 (0.582–0.825) | 0.692 (0.567–0.818) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 0.642 (0.573–0.710) | 0.632 (0.562–0.702) |

| Positive predictive value (95% CI) | 0.362 (0.270–0.454) | 0.350 (0.257–0.442) |

| Negative predictive value (95% CI) | 0.882 (0.828–0.937) | 0.878 (0.822–0.934) |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; AUPRC, area under the precision-recall curve; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the primary outcome. The receiver operating characteristic curve (line) is presented with its 95% confidence interval (shades). DL, deep learning; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

The predictive performance of the deep learning algorithm using Lead I was lower than that of the 12-lead ECG–based prediction (AUROC 0.68; 95% CI 0.59–0.77; Table 3; Supplementary material online, Figure S1). However, the NPV remained consistent at 0.88 (95% CI 0.82–0.95).

Table 3.

Model performance in secondary outcome

| Deep learning algorithm | |

|---|---|

| AUROC (95% CI) | 0.678 (0.591–0.765) |

| AUPRC (95% CI) | 0.432 (0.340–0.564) |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 0.796 (0.689–0.904) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 0.444 (0.373–0.515) |

| Positive predictive value (95% CI) | 0.293 (0.219–0.366) |

| Negative predictive value (95% CI) | 0.883 (0.818–0.948) |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; AUPRC, area under the precision-recall curve.

Patients who underwent echocardiography within 2 weeks (n = 144) were further evaluated for the model performance in predicting LVSD (see Supplementary material online, Table S2 and Figure S2). In this subgroup, the predictive performance of the deep learning algorithm showed improvement for both 12-lead ECG–based algorithm (AUROC 0.80, 95% CI 0.71–0.90; AUPRC 0.65, 95% CI 0.51–0.77) and the Lead I–based algorithm (AUROC 0.75, 95% CI 0.66–0.85; AUPRC 0.48, 95% CI 0.34–0.63). Additionally, the NPV was enhanced, reaching its peak in the Lead I–based algorithm [0.96 (95% CI 0.91–1.00)].

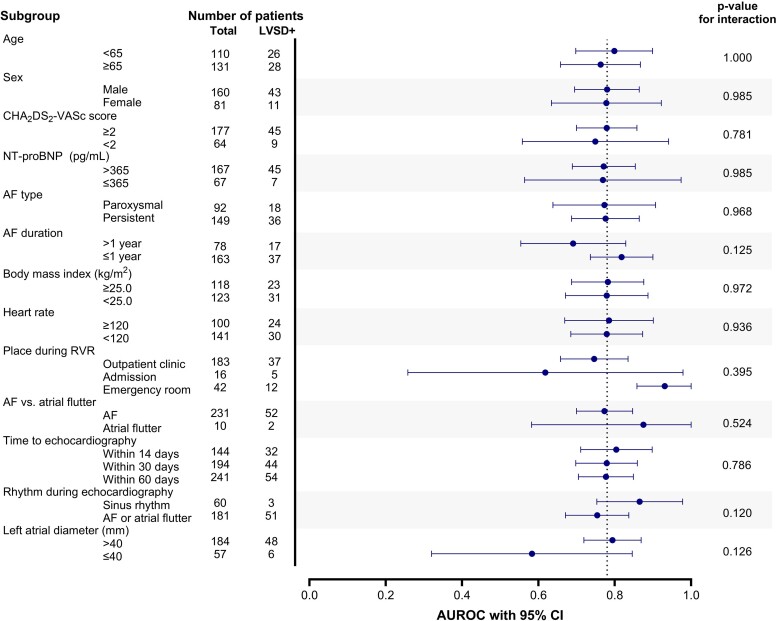

The model’s performance for the primary outcome was assessed across various subgroups (see Supplementary material online, Table S3; Figure 3). Although no significant interaction was observed between different subgroups, there was a tendency towards better performance in certain scenarios, including (i) patients who underwent echocardiography within 14 days (AUROC 0.80, 95% CI 0.71–0.90), (ii) AF detected within 1 year (AUROC 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.90), (iii) AF with RVR occurring in the emergency department (AUROC 0.93, 95% CI 0.86–1.00), (iv) patients with atrial flutter during RVR (AUROC 0.88, 95% CI 0.58–1.00), and (v) patients who converted to sinus rhythm during echocardiography assessment (AUROC 0.87, 95% CI 0.75–0.98).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of deep learning algorithm to predict left ventricular systolic dysfunction (0.777) was set as reference. LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; AF, atrial fibrillation; RVR, rapid ventricular response.

Four variables were identified as predictors of the primary outcome (Table 4). An increase in QRS duration, NT-proBNP, or LV mass and a decrease in LV mass index were found to be associated with an increased risk of having LVSD.

Table 4.

Predictors of primary outcome

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place during AF RVR | 0.932 | 0.543–1.568 | 0.789 |

| Atrial flutter | 2.340 | 0.333–16.281 | 0.381 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 1.010 | 0.942–1.073 | 0.784 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 1.030 | 1.010–1.051 | 0.017 |

| QT interval (ms) | 1.010 | 0.951–1.051 | 0.725 |

| QTc interval (ms) | 1.000 | 0.961–1.041 | 0.875 |

| R-axis | 0.990 | 0.990–1.000 | 0.093 |

| T-axis | 1.000 | 0.990–1.000 | 0.306 |

| Female sex | 1.786 | 0.427–7.463 | 0.427 |

| Age at AF diagnosis | 1.010 | 0.951–1.073 | 0.763 |

| Persistent AF | 1.310 | 0.527–3.320 | 0.558 |

| NT-proBNP | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.005 |

| New onset AF | 1.246 | 0.449–3.525 | 0.676 |

| Duration of AF (years) | 1.062 | 0.942–1.197 | 0.348 |

| Time to echocardiography (days) | 0.990 | 0.961–1.010 | 0.290 |

| AF or atrial flutter during echocardiography | 1.030 | 0.346–3.096 | 0.957 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 0.000 | 0.000–0.990 | 0.053 |

| Left ventricular diastolic dimension (mm) | 1.073 | 0.852–1.433 | 0.579 |

| Left ventricular systolic dimension (mm) | 1.105 | 1.000–1.234 | 0.050 |

| Septal thickness (mm) | 1.492 | 0.869–2.801 | 0.162 |

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) | 1.020 | 0.595–1.859 | 0.938 |

| Aorta thickness (mm) | 0.970 | 0.896–1.051 | 0.517 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 1.000 | 0.932–1.073 | 0.990 |

| Left ventricular mass (g) | 1.083 | 1.000–1.174 | 0.051 |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2) | 0.844 | 0.719–0.980 | 0.033 |

| Estimated pulmonary artery pressure (mmHg) | 1.000 | 0.942–1.051 | 0.898 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 0.691 | 0.320–1.448 | 0.330 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.020 | 0.869–1.197 | 0.832 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1.094 | 0.507–2.340 | 0.819 |

| Thyroid disease | 2.181 | 0.827–6.050 | 0.120 |

| Hypertension | 1.616 | 0.595–4.482 | 0.346 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.185 | 0.333–4.263 | 0.789 |

| Vascular disease | 4.055 | 0.819–23.336 | 0.096 |

| Heart failure | 2.460 | 0.852–7.463 | 0.101 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 3.254 | 0.566–19.886 | 0.193 |

Increase of odds ratio means increased probability of having left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

AF, atrial fibrillation; RVR, rapid ventricular response; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

The present study investigated the efficacy of deep learning algorithms in predicting LVSD and its applicability in the clinical practice for diagnosing patients with AF and RVR. Despite the inherent challenge in predicting LV function in patients presenting with AF and RVR, the 12-lead ECG–based algorithm demonstrated fair performance (AUROC 0.78). Patients with a shorter time window between 12-lead ECG and echocardiography exhibited improved performance (AUROC 0.80). Deep learning algorithms yielded excellent NPVs in both the 12-lead and 1-lead ECG–based algorithm. The high NPV in patients with AF and RVR potentially facilitates informed choices in drug selection for rate and rhythm control in an outpatient setting.

Prediction of heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

The deep learning algorithm employed in this study has undergone validation in large-sized cohort in previous studies.12,17 The 12-lead ECG–based algorithm, initially developed with data from 22 765 patients, was externally validated (n = 5901), demonstrating good performance in predicting heart failure with reduced LVEF (AUROC 0.84).12 Additionally, the developmental data included ECGs with AF or atrial flutter, constituting less than 20% of the total cohort. Regardless of algorithm types, heart rate and the presence of AF or atrial flutter were identified as important variables influencing predictive performance. In essence, predicting LV function was more challenging in patients presenting with tachycardia or AF. The sensitivity of LVSD prediction using 12-lead ECG was 70.4%, whereas it was improved as 78.1% in subgroup that underwent echocardiography within 14 days. Similarly, in single-lead ECG–based prediction, the sensitivity was 79.6%, which was improved as 93.8% in 14 days interval subgroup. Based on the cohort of patients with AF and RVR, this study successfully validated the performance of deep learning algorithm in predicting LVSD.

Clinical implications

Patients detected with AF are recommended for early evaluation, focusing on assessing structural heart disease and substrate. Particularly, patients in the acute phase of AF with RVR require prompt evaluation of the LV function to guide further treatment strategies. Distinguishing LVSD in patients with AF is essential, as it limits the spectrum of drug choices for rate rhythm control. Particularly, calcium channel blockers or class Ic antiarrhythmic drugs are contraindicated in this population. However, patients with stable AF are typically evaluated and treated in outpatient settings, where real-time, quantitative assessment of LVEF is challenging. In addition, presence of AF and RVR may impair the diagnostic value of laboratory markers such as NT-proBNP.18 Consequently, deep learning algorithms predicting LVEF may provide additional information for further decision-making. In our study, the validation of deep learning algorithms in the AF RVR cohort revealed fair AUROC and high NPV that was higher than that of NT-proBNP. The high NPV is advantageous in excluding individuals with LVSD, allowing for the informed selection of appropriate drugs for rate or rhythm control. Therefore, the deep learning–based prediction of LVSD may extend clinical information needed for further treatment in circumstances where echocardiography is not feasible. Although deep learning algorithm may not fully substitute echocardiography, earlier prediction of LV function using a deep learning algorithm may be beneficial, leading to earlier pharmacotherapy to relieve AF-related morbidities. For instance, deep learning algorithm could be used to exclude patients with heart failure with reduced EF, and appropriate rate control and antiarrhythmic drugs could be prescribed without several weeks of delay. Earlier pharmacotherapy enabled by deep learning algorithm is consistent to the paradigm of early rhythm control in AF, which may reduce cardiovascular events and further progression of AF.19,20 High NPV observed in single-lead ECG–based prediction may expand its applicability into various settings such as wearable ECGs (smartwatch) and in-hospital telemetry monitoring.

Assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction during atrial fibrillation? Or sinus rhythm?

In our cohort, although all patients presented AF (or atrial flutter) and RVR at enrolment, 24.9% restored sinus rhythm when the echocardiography was performed. Assessing echocardiography during AF may underestimate the true LVEF, especially in those who present RVR. In addition, there is a high chance of LVEF improvement in patients who restored sinus rhythm.21 There is a gap of evidence in the guidelines, which do not specify the treatment strategies according to the rhythm that the LVEF was assessed.1,5 On the other hand, the LVSD predicted by deep learning algorithm is not influenced by the cardiac rhythm—whether the rhythm is AF or sinus. Subgroup that restored sinus rhythm during echocardiography showed higher predictive performance compared with that maintained AF or atrial flutter (AUC 0.865 vs. 0.754) without statistical difference (P = 0.120, Figure 3; Supplementary material online, Table S2). This may indicate that deep learning algorithm may have higher predictive value in detecting LVSD due to structural substrate (such as dilated cardiomyopathy or ischaemic heart disease) than those with LVSD related to AF. In addition, applying deep learning algorithm to predict LVSD may overcome the practical limitation—of whether the patient rhythm is AF or not—that disturbs identification of the ‘true’ LVEF.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the lack of strict protocols in terms of the time interval between 12-lead ECG and echocardiography introduces variability among patients. Echocardiographic evaluation during AF may underestimate the true LVEF, and restoration of sinus rhythm in the meanwhile may improve LVEF, leading to the discrepancy of predicted LVEF (by deep learning algorithm) and calculated LVEF (by echocardiography). This variability reflects the real-world outpatient setting, where the time until echocardiographic assessment can be even longer than the predefined 6 weeks. Second, the inclusion of only 12-lead ECGs converted into an analysable format in the central server may introduce bias. Since ECGs that were taken by portable device required additional step of sending the ECGs to the central server, excluded cases may represent a significant proportion taken in acute or critically ill condition (i.e. in the intensive care unit), potentially limiting the applicability of deep learning–based prediction in patients with acute and haemodynamically unstable conditions. Third, although our study focused on identifying the presence of LVSD, the aetiology of LVSD was not considered in the prediction. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction in AF is not equivalent to LVSD in sinus rhythm, since AF itself may contribute to the development of LVSD. In a previous study, three key features in beat-to-beat patterns of AF were relevant to AF-induced heart failure, which resulted in high specificity (91.4%) and positive predictive value (87.0%).22 Deep learning algorithm used in our study was originally developed in mostly sinus rhythms, and beat-to-beat variability (RR intervals) was not initially considered in the model development. However, a small proportion of AF or atrial flutter (11.8%) were included in original model, and beat-to-beat variability may had been trained as a hidden feature to predict LVSD in AF. Further consideration of the aetiology of LVSD such as AF-related LVSD that is reversible with sinus conversion may also facilitate clinical intervention. Fourth, intrinsic limitations may lie in the prediction model and model performance when applying it in clinical practice. For instance, NPV of 0.88 may lead to inappropriate prescription of contraindicated medication in up to 12% of patients with AF and RVR. Whether the benefit of earlier pharmacotherapy to be free from RVR and restore sinus rhythm outweighs the hazards of inappropriate drug choice is unknown. Treatment strategy based on the deep learning algorithm should be accompanied by physician’s clinical insight and relevant clinical circumstances. Lastly, the study investigated the performance of the deep learning algorithm based on echocardiographic assessment of LVEF, and a direct comparison with conventional echocardiography was not conducted. Further prospective trials are needed to assess the non-inferiority of the deep learning algorithm compared with conventional echocardiography and warrant its broader use in clinical practice.

Conclusion

In patients presenting with AF and RVR, the 12-lead ECG–based deep learning algorithm demonstrated good performance in predicting LVSD. The high NPV, particularly in excluding LVSD, potentially facilitates rapid and enhanced selection of drug therapy in an outpatient, emergency or primary care setting. Early assessment of LV systolic function using the deep learning algorithm may prove beneficial for the guideline-directed rate control strategy in patients with AF and RVR, leading to better symptom control and optimization of AF-related morbidities.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Joo Hee Jeong, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Sora Kang, Medical Research Team, Medical AI Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Hak Seung Lee, Medical Research Team, Medical AI Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Min Sung Lee, Medical Research Team, Medical AI Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jeong Min Son, Medical Research Team, Medical AI Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Joon-myung Kwon, Medical Research Team, Medical AI Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Hyoung Seok Lee, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Yun Young Choi, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

So Ree Kim, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Dong-Hyuk Cho, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Yun Gi Kim, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Mi-Na Kim, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Jaemin Shim, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Seong-Mi Park, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Young-Hoon Kim, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Jong-Il Choi, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, 73 Goryeodae-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02841, Republic of Korea.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Digital Health.

Author contribution

J.-I.C. had full access to all the data in this study and takes responsibility for its integrity and analytical accuracy. The study concept and design were developed by J.H.J., J.K., and J.-I.C.. The data analysis and interpretation were performed by J.H.J., J.K, S.K., M.S.L., J.M.S., and J.-I.C.. The primary manuscript was drafted by J.H.J., and J.-I.C. and edited by J.H.J., J.-I.C., J.K., S.K., M.S.L., J.M.S., and D.-H.C.. The data collection was performed by J.H.J., H.S.L., Y.Y.C., Y.G.K. S.R.K., D.-H.C., M.-N.K., S.-M.P., Y.H.K., J.S., and J.-I.C.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Korea University Medicine Anam Hospital and official review committee approved this specific study (IRB No. 2023AN0223). The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Medicine Anam Hospital, due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Funding

This work was supported by a Korea University grant (J.-I.C.) and a grant from Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea (J.-I.C.). The funders had no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation, trial design, patient recruitment, or any other aspects pertinent to the study.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its supplementary material.

References

- 1. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:104–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daoud EG, Weiss R, Bahu M, Knight BP, Bogun F, Goyal R, et al. Effect of an irregular ventricular rhythm on cardiac output. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:1433–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1363–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024;149:e1–e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rahimi AR, York M, Gheewala N, Markson L, Hauser TH, Manning WJ. Trends in outpatient transthoracic echocardiography: impact of appropriateness criteria publication. Am J Med 2011;124:740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ng SM, Naqvi D, Bingcang J, Cruz G, Nose R, Lloyd G, et al. Feasibility, diagnostic performance and clinical value of an abbreviated echocardiography protocol in an out-patient cardiovascular setting: a pilot study. Echo Res Pract 2022;9:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Ascenzo F, De Filippo O, Gallone G, Mittone G, Deriu MA, Iannaccone M, et al. Machine learning-based prediction of adverse events following an acute coronary syndrome (PRAISE): a modelling study of pooled datasets. Lancet 2021;397:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lu L, Zhu TT, Ribeiro AH, Clifton L, Zhao E, Zhou JD, et al. Decoding 2.3 million ECGs: interpretable deep learning for advancing cardiovascular diagnosis and mortality risk stratification. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2024;5:247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kwon JM, Kim KH, Eisen HJ, Cho Y, Jeon KH, Lee SY, et al. Artificial intelligence assessment for early detection of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction based on electrocardiographic features. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2021;2:106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yagi R, Goto S, Katsumata Y, MacRae CA, Deo RC. Importance of external validation and subgroup analysis of artificial intelligence in the detection of low ejection fraction from electrocardiograms. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2022;3:654–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kwon JM, Kim KH, Jeon KH, Kim HM, Kim MJ, Lim SM, et al. Development and validation of deep-learning algorithm for electrocardiography-based heart failure identification. Korean Circ J 2019;49:629–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:233–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kwon JM, Jo YY, Lee SY, Kang S, Lim SY, Lee MS, et al. Artificial intelligence-enhanced smartwatch ECG for heart failure-reduced ejection fraction detection by generating 12-lead ECG. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12:654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee BT, Jo YY, Lim SY, Song Y, Kwon JM. Efficient data augmentation policy for electrocardiograms. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, 2022. p.4153–4157. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee Y, Choi B, Lee MS, Jin U, Yoon S, Jo Y-Y, et al. An artificial intelligence electrocardiogram analysis for detecting cardiomyopathy in the peripartum period. Int J Cardiol 2022;352:72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jung YM, Kang S, Son JM, Lee HS, Han GI, Yoo AH, et al. Electrocardiogram-based deep learning model to screen peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023;5:101184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richards M, Di Somma S, Mueller C, Nowak R, Peacock WF, Ponikowski P, et al. Atrial fibrillation impairs the diagnostic performance of cardiac natriuretic peptides in dyspneic patients: results from the BACH study (Biomarkers in ACute Heart Failure). JACC Heart Fail 2013;1:192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nattel S, Guasch E, Savelieva I, Cosio FG, Valverde I, Halperin JL, et al. Early management of atrial fibrillation to prevent cardiovascular complications. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1448–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim D, Yang PS, You SC, Sung JH, Jang E, Yu HT, et al. Treatment timing and the effects of rhythm control strategy in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2021;373:n991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muller-Edenborn B, Minners J, Allgeier J, Burkhardt T, Lehrmann H, Ruile P, et al. Rapid improvement in left ventricular function after sinus rhythm restoration in patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. Europace 2019;21:871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luongo G, Rees F, Nairn D, Rivolta MW, Dossel O, Sassi R, et al. Machine learning using a single-lead ECG to identify patients with atrial fibrillation-induced heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:812719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its supplementary material.