INTRODUCTION

When I began lecturing on marriage to medical students and physicians about 25 years ago, I used a cartoon to introduce my lectures. The cartoon showed 2 physicians having lunch together in the hospital. The caption says: “Show me a doctor whose wife is happy, and I'll show you a man who's neglecting his practice.”

Table 1.

| Expectations that people bring to a relationship |

|---|

|

Fast-forward now to the 21th century and consider the changed demographics: 50% of physicians are women, lots of spouses are men, many physicians do not have wives or husbands but “partners” (who may be the opposite or same sex), and few physicians have or make the time to eat together in the hospital cafeteria.

But, with some gender-neutral modernizing, isn't the caption still apt? Aren't physicians still torn between their calling—the needs of their patients—and the needs of their families? Don't some physicians still think that their patients come first and that their spouses or partners must simply understand?

In this article, I attempt to answer 4 questions:

What do we know about healthy, intimate relationships?

What are some of the unique challenges to a relationship posed by a career in medicine?

What is the effect of a healthy relationship on physician well-being?

What are some strategies to create and maintain relationship intimacy?

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT HEALTHY, INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS

When we consider a “healthy relationship,” we conceptualize an alliance of 2 mature human beings who are developmentally ready to form a union that will meet their individual needs and ensure their personal growth in the life stages and cycles that lie ahead. The texture of this “coming together” depends on many factors, such as love, affection, sex, companionship, communication, financial security, intimacy, and commitment.

Persons who come together in a relationship have many expectations of each other (see box). Although men and women have similar expectations, the prioritizing and importance may differ. A healthy and functioning relationship requires a sense of working harmoniously together, getting things done, planning, and dreaming.

There are many definitions of “intimacy,” most of them including factors such as affection, expressiveness, sexuality, cohesion, compatibility, autonomy, conflict resolution, and identifying as a couple.1

Other definitions include a sense of connection and mutuality and notions of feeling close and trusting each other.2 Some people describe feeling honored by their partner and feeling special. The more intimacy, the fewer the conflicts in the relationship.

THE UNIQUE CHALLENGES TO A RELATIONSHIP POSED BY A CAREER IN MEDICINE

Although those who become physicians are far from homogeneous, most medical students tend to be academically focused, studious, and hard-working and take their profession seriously.3 Their role models range from academic superstars with impressive research credentials and international acclaim to committed clinician-teachers who are at the hospital 7 days a week.

Many of their heroes lead lives that are desperately out of balance—they overwork and suffer silently and ashamedly with low-grade depression, substance abuse, family strain, and loneliness outside of medicine. The traits that make good physicians and teachers, such as control, perfectionism, and dedication, often work against creating and maintaining healthy relationships and marriages.4

Women in medicine have additional challenges.5 Most argue that they love medicine, but their definition of a “healthy self” often includes a healthy relationship and children. They may suffer role strain while trying to juggle being a physician, wife or partner, mother, daughter, and volunteer—let alone finding time for themselves.6

Many women physicians are inherently prone to feelings of guilt, which are further fueled by outside forces. Patients may feel abandoned when their physician becomes pregnant or may voice disappointment toward their physician for working part-time only; medical colleagues, employers, or program directors may imply that women physicians are less “dedicated”; partners or spouses can be insensitive and controlling and want them to generate more income; and many people simply do not understand that women are usually also the “CEOs” of the home, which is an enormous responsibility.

Finally, there are many groups and individuals for whom a career in medicine is hard on healthy relationships (see box).

Table 2.

| Circumstances in which a medical career is likely to affect personal relationships |

|---|

|

WHY PHYSICIANS FIND IT HARD TO FORM A HEALTHY RELATIONSHIP

Physicians who can balance work, family and physical, emotional, and spiritual needs in some harmony are happier, healthier, clearer in thought, more energetic, and more accepting. Yet, this is a goal that proves elusive for most physicians.

Although many of the reasons for this elusiveness are external, as discussed, some are internal. Few physicians come from perfectly functional families. Many are “wounded healers” in that they have experienced situations such as poverty, hunger, war, or forced migration. Many physicians have experienced family heartache, abuse, discrimination, or disease. These challenges inform a person's decision to become a physician. Creating and cultivating a healthy, intimate relationship is a further challenge to physicians, who have great strengths but also vulnerabilities.7

Today's medical students and young physicians are the largest cohort of adult children of divorce that have ever studied medicine. How much they have been affected by the divorce of their parents certainly affects their personal relationships. Some approach intimacy and commitment to relationships with ambivalence and fear.8

Communicating in a mature and giving way in a relationship or marriage is not innate. It must be learned. And this type of communicating is not taught in medical school, either in formal teaching or by example. Indeed, the expectations and rigors of training in some residencies are “toxic” and frankly antithetical to healthy relationships at home.

HOW A HEALTHY RELATIONSHIP CONTRIBUTES TO PHYSICIAN WELL-BEING

Starting the day with a conversation with a spouse or partner can be centering. A hug or kiss going out the door is profoundly human, and it reinforces the fact that no matter what happens today at work, you are not alone. You can make a telephone call during the day. You can look forward to reconnecting with the person who loves you, who cares about you, and with whom you share your life.

If you have a tough day and need support, you can count on your partner to be there, to listen, to give perspective, and to provide support. And it is a blessing to reciprocate—having someone to love and to nurture is an integral part of being human. This is not the same as what physicians give to their patients in the doctor-patient covenant. It is deeper, exquisite, and unique.

Physicians who have children may find the challenges more manageable and the joys more intense when their marriage is happy. This can translate into greater well-being. Indeed, the “alliance of couplehood” can be a formidable force—one that can give each of the persons more self-worth, purpose, and creativity.

Physicians living with illness find that the experience is less frightening when they are fortunate enough to have a loving spouse or partner at their side.

STRATEGIES TO CREATE AND MAINTAIN RELATIONSHIP INTIMACY

Much has been written about the medical marriage and ways of preventing, recognizing, and overcoming conflict and strain.9,10,11,12,13,14,15 Here are a few simple suggestions:

The culture of medicine has to change

Physicians need to take better care of themselves and not feel guilty about working fewer hours per week, taking more vacation, pursuing other vocations, and protecting time for exercise and personal reflection. It is impossible to give lovingly and graciously to a relationship if you are exhausted and have not had enough time alone.

Set aside time and attention for the relationship

All relationships require care and patience to flourish. Physicians must give more attention to their relationships, both in thought and deed. One of the most common dialogues in my office is this:

Doctor's spouse: “I don't think you love me anymore.”

Doctor (shocked and surprised): “Honey, how can you say that? You know I love you!”

Doctor's spouse: “Then why don't I feel it?”

Doctor: “Well, I don't know.”

Doctor's spouse: “What I do feel is about number 4 or 5 on your list of priorities.”

Learning to say “no” is a lifelong challenge for physicians. It does get easier, and it is the only way to preserve balance in one's life.

Physicians should have their own physician

All physicians should have a primary care physician whom they trust, respect, and visit whenever they have concerns about their health or functioning. For example, it is hard to be an active participant in a healthy relationship if you are burned out, clinically depressed, or abusing alcohol. Physicians who have a personal physician are less likely to self-medicate.

Tap community resources

A lot of community resources are available to physicians and their partners (see box). Many couples can improve their situation on their own by reading books on relationships, completing questionnaires, and doing exercises together.16 Signing up for marital enrichment courses—secular or religious—and attending workshops and seminars earmarked for couples can also be helpful.

Seek professional help for the relationship

Physicians with unrelenting strain in their relationships should go for couples therapy. Unfortunately, stigma often prevents couples from seeking help.17 Physicians—and those who treat them—are all too aware of the shame and sense of failure that accompanies relationship discord. Many physicians tend to be self-reliant (“We're smart people, we can fix this ourselves”), private (“I'm not airing my dirty laundry in public”), and sometimes arrogant (“What do marital counselors know? I've got a lot more education than they do”). Couples therapy is not only of proven value as an intervention,18,19,20 it can also be a comforting experience.

Summary points

A healthy, intimate relationship is vital to most physicians

Professional responsibilities and/or a physician's temperament may be at odds with this goal

The medical profession needs a cultural shift from the belief that physicians' calling transcends family life

All relationships require care, patience, and nurturing

Couples therapy often restores intimacy, happiness, and personal well-being

Additional resources

The Gottman Institute, Seattle, WA. To obtain the latest books, videotapes, and workshop schedules, telephone: 1-888-523-9042, or visit: http://www.gottman.com

American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, 1133 15th St, NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20005; telephone: (202) 452-0109. Fully accredited, with more than 23,000 practitioners in marital and family therapy. To find a therapist in your area: http://www.aamft.org

American Medical Association Alliance. Publications of interest to physicians and their spouses. AMA Alliance, 515 N State St, Chicago, IL 60610

State Physician Health Programs. Contact your state medical association for telephone numbers and local resources for marital, relationship, and family concerns

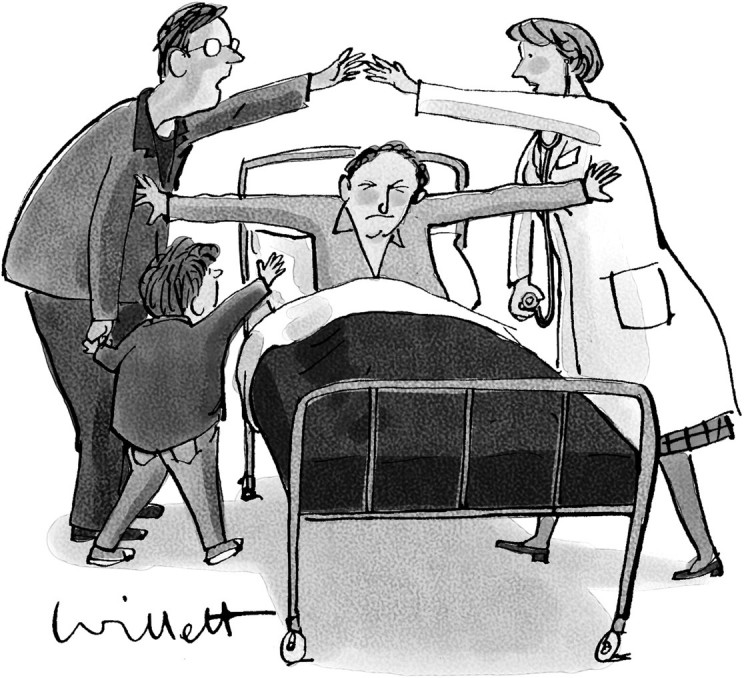

Figure 1.

© Malcolm Willett

Competing interests: None declared

Author: Michael Myers is a psychiatrist and specialist in physician health. He is the director of the marital therapy clinic at St Paul's Hospital and clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia, both in Vancouver, British Columbia.

References

- 1.Waring EM, Tillman MP, Frelick L, Russell L, Weisz G. Concepts of intimacy in the general population. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980;168: 471-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan J. Chapter 5, The meaning of mutuality. In: Jordan JV, Kaplan AG, Miller JB, Stiver IR, Surrey JL, eds. Women's Growth in Connection. New York: Guilford Press; 1991.

- 3.Dickstein LJ. Medical students and residents: issues and needs. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The Handbook of Physician Health. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2000: 161-179.

- 4.Ellis JJ, Inbody DR. Psychotherapy with physicians' families: when attributes in medical practice become liabilities in family life. Am J Psychother 1988;42: 380-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Notman MT. Physician temperament, psychology, and stress. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The Handbook of Physician Health. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2000: 39-51.

- 6.Myers MF. Overview: the female physician and her marriage. Am J Psychiatry 1984;141: 1386-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers MF. Physicians and intimate relationships. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The Handbook of Physician Health. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2000: 52-79.

- 8.Myers MF. Intimate Relationships in Medical School: How to Make Them Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000.

- 9.Gabbard GO, Menninger RW. Medical Marriages. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1988.

- 10.Myers MF. Doctors' Marriages: A Look at the Problems and Their Solutions. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum; 1994.

- 11.Myers MF. Doctor-doctor marriages: a prescription for trouble? Med Econ 1998;75: 98-100, 102, 107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myers MF. Doctors and divorce: don't let your practice kill your marriage. Med Econ 1998;75: 78-80, 83, 87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers MF. Doctors and divorce: when medicine, marriage, and motherhood don't mix. Med Econ 1998;75: 100-102, 105, 109-110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers MF. Doctors and divorce: residency and marriage: oil and water? Med Econ 1998;75: 152-156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers MF. Doctors and divorce: goodbye to medicine, or to your marriage? Med Econ 1998;75: 200-202, 207-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotile WM, Sotile MO. The Medical Marriage: Sustaining Healthy Relationships for Physicians and Their Families. revised ed. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2000.

- 17.Myers MF. When physicians become our patients. Psychiatric Times August 2000;17: 45-46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perlmutter RA. A Family Approach to Psychiatric Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997: 49-70.

- 19.O'Leary KD, Beach SRH. Marital therapy: a viable treatment for depression and marital discord. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147: 183-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson NS, Addis ME. Research on couple therapy: what do we know? where are we going? J Consult Clin Psychol 1993;61: 85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]