Abstract

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in older children is generally caused by conditions like esophagitis, esophageal variceal rupture, and peptic ulcer disease. However, it is rare for bleeding to result from a ruptured vascular aneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery, particularly when associated with peptic ulcer disease. This report describes a case involving a 13-year-old male who presented with severe upper GI bleeding and hemodynamic instability, requiring blood transfusion. During an emergency upper GI endoscopy, a bleeding gastric ulcer classified as Forrest IIB was identified. The bleeding was managed initially with endoscopic hemostasis and surgical suturing. Despite these interventions, the patient experienced recurrent bleeding. Further investigation with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a vascular aneurysm in the gastroduodenal artery. The patient subsequently underwent successful endovascular embolization, as confirmed by digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Following this procedure, there were no further episodes of GI bleeding. This case highlights the critical need for thorough diagnostic evaluation using contrast-enhanced CT and endoscopy in managing complex GI bleeding cases. Early detection and appropriate intervention are essential, especially in pediatric patients where the cause of bleeding may be rare and severe.

Keywords: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding, Peptic ulcer disease, Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm, Endovascular embolization, Pediatric gastroenterology

Learning objectives .

The primary learning objective of this manuscript is to understand the complexity and rarity of managing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in pediatric patients, particularly when caused by the combination of peptic ulcer disease and a ruptured gastroduodenal artery aneurysm. It emphasizes the critical importance of utilizing advanced imaging techniques like contrast-enhanced CT for accurate diagnosis and highlights the significance of timely and appropriate interventions, including endovascular embolization, to improve patient outcomes and reduce mortality in such challenging cases.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a significant cause of mortality in children, with a reported fatality rate of 5%-10% worldwide [1]. The etiology of upper GI bleeding varies by age group, and effective treatment is highly dependent on early identification of the underlying cause. Although aneurysms of the gastroduodenal artery account for only 1.5% of all visceral artery aneurysms [2], their rupture can lead to upper GI bleeding with a mortality rate ranging from 25-70% [2]. This underscores the critical importance of early detection of visceral artery aneurysms through advanced imaging techniques, which subsequently guides the selection of appropriate interventions, with endovascular treatment being the preferred option [3].

Case presentation

A 13-year-old male patient with a history of peptic ulcer disease, diagnosed 6 months prior, presented with severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient had not received continuous treatment for his ulcer. The condition initially manifested with symptoms of hematemesis and melena, leading to his admission at QBT Hospital, where he was diagnosed with severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding, likely due to peptic ulcer disease. He received a transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells, and his symptoms of hematemesis and melena temporarily subsided. However, after 5 days of treatment, the patient experienced a recurrence of massive hematemesis, followed by syncope, hypovolemic shock, and severe anemia. He was administered intravenous fluids at 20ml/kg and 1 unit of packed red blood cells before being transferred to the City Children's Hospital.

Upon evaluation in the Emergency Department, the patient was found to be pale, with a heart rate of 80 bpm and blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg. His bedside hematocrit was 22%. He was transfused with 2 additional units of packed red blood cells, and his hematemesis ceased, though he continued to pass dark red blood in his stools. The patient's hematocrit stabilized between 28-30%, coagulation studies were within normal limits, and his condition was diagnosed as severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding, which appeared to be under control. He was then admitted to the Gastroenterology Department for continued treatment.

During his hospitalization, the patient continued to pass black stools, although his vital signs remained stable. On the ninth day, he abruptly experienced a significant episode of bright red hematemesis, approximately 100ml in volume, accompanied by pallor and hemodynamic instability. Following stabilization, an urgent endoscopy was performed, revealing nodular gastritis with 2 large duodenal ulcers measuring 15 × 10mm and 27 × 15mm, classified as Forrest IIB. The ulcers were surrounded by a significant amount of blood clots, and active bleeding from the gastric cardia was observed (Fig. 1), though the precise source of the bleeding could not be identified. Hemostasis was attempted with adrenaline injection around the bleeding site, and blood clots were removed.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic images of the stomach and duodenum. (A) Large amount of clotted blood at the fundus of the stomach. The white arrow points to an area of active bleeding. (B) Nodular gastritis of the duodenal mucosa. The white arrow indicates a superficial ulcer that is actively bleeding.

Two days postendoscopy, the patient continued to exhibit bright red hematemesis and persistent melena. A second endoscopy revealed extensive ongoing bleeding within the stomach, with large blood clots obscuring the bleeding vessel. Given the difficulty in localizing the source of bleeding, the patient was taken to surgery for an open exploration and hemostasis. During surgery, the segment of the duodenum was found to be filled with blood clots, which were concentrated primarily at the gastric base. After removing the clots, 2 to 3 small, edematous areas of mucosa, each measuring 2 × 2mm, were identified as sources of minor bleeding. Hemostasis was achieved through suturing, and no additional bleeding sites were detected.

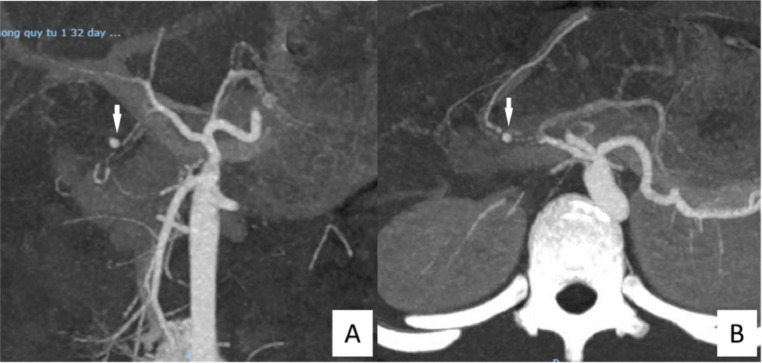

Five days after the combined endoscopic and surgical intervention for hemostasis, the patient continued to experience substantial hematemesis, with ongoing gastrointestinal bleeding. A multidisciplinary team consultation led to the decision to perform a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen to assess the vascular structures. The CT scan revealed a focal area of strong contrast enhancement, approximately 2 cm from the origin of the common hepatic artery, along the gastroduodenal artery, near the inner wall of the proximal duodenum. The lesion, measuring approximately 4 × 5.7mm with well-defined borders, was highly suggestive of a vascular aneurysm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Abdominal vessel computed tomography angiography (CTA) images. (A) The white arrow points to a pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery, approximately 2 cm distal to the common hepatic artery origin. (B) The white arrow indicates a hyperemic nodule measuring 4 × 5.7mm with well-defined margins along the course of the gastroduodenal artery.

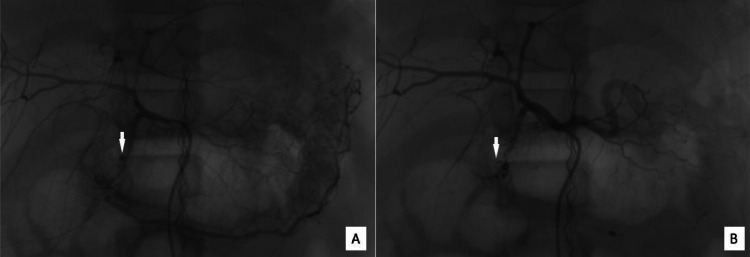

Subsequently, the patient underwent endovascular treatment with digital subtraction angiography (DSA), during which coil embolization was performed to occlude the distal segment of the gastroduodenal artery, as well as the middle third of the gastroduodenal artery and the proximal left gastric artery as a precaution. Following the endovascular intervention, the patient's hematemesis and melena resolved within 6 days, and he was discharged after 1 month of treatment with no signs of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) images of the gastroduodenal artery. (A) The white arrow points to a pseudoaneurysm in the gastroduodenal artery before intervention. (B) Postintervention image where the white arrow indicates the site of complete occlusion of the aneurysm by coils.

Discussion

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding refers to lesions occurring in the digestive tract from the esophagus to the Treitz ligament and is a common indication for hospitalization in children. According to Susan Owensby et al. (2015), the incidence of upper GI bleeding in children in France is approximately 1-2 per 10,000 cases [4], though similar data for Vietnam is not yet available. Globally, upper GI bleeding accounts for 20% of pediatric hospital admissions due to gastrointestinal hemorrhage [5], with a mortality rate ranging from 5% to 10% [1].

In Vietnam, a study conducted from February 2020 to February 2021 at Hue Central Hospital revealed that the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in children over 5 years old is peptic ulcer disease [6]. From these statistics, it is evident that the rupture of abdominal vascular aneurysms is not a common cause of upper GI bleeding. Vascular aneurysms are classified into 2 types: true aneurysms, which involve all 3 layers of the vessel wall, and pseudoaneurysms, which typically result from surgical complications. The leading cause of true aneurysms is atherosclerosis, while pseudoaneurysms are primarily caused by surgical complications. In cases where multiple aneurysms are present, the underlying cause may be a connective tissue disorder or a vascular collagen disease, warranting genetic testing [3].

Visceral artery aneurysms have an estimated incidence of 0.01% to 0.2%, and up to 10% in patients with pancreatitis [7]. Among visceral artery aneurysms, the most common are splenic artery aneurysms (32.8%), followed by renal artery aneurysms (22%) [2]. Although visceral artery aneurysms are relatively rare, the mortality rate for ruptured aneurysms can be as high as 25-70% [2], with pseudoaneurysms rupturing at a rate of 76.3% compared to 3.1% for true aneurysms.

Gastroduodenal artery aneurysms account for approximately 1.5% of visceral artery aneurysms, making them one of the rarest forms [2]. The most common causes of gastroduodenal artery aneurysms are pancreatitis (47%), alcohol abuse (25%), and peptic ulcer disease (17%). These aneurysms can also occur in the context of genetic syndromes (such as Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), cirrhosis, or other vascular abnormalities [2]. No association has been observed between gastroduodenal artery aneurysms and other abdominal aneurysms [3]. The rupture rate for gastroduodenal artery aneurysms can reach 75% [8], with a mortality rate of up to 40% [2].

In the case presented in this report, we believe that the patient had a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery, likely caused by peptic ulcer disease. The patient had been diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease 6 months prior to hospitalization but had not received continuous treatment. Endoscopic findings upon admission also indicated peptic ulcer disease. Reports of ruptured gastroduodenal artery aneurysms in children are rare. We found 1 case report of a gastroduodenal artery aneurysm in a child following biliary-enteric anastomosis for a post-traumatic pancreatic pseudocyst (Zarin et al., 2018) [9] and another case attributed to severe infection (Kavitha et al., 2021) [10].

For diagnosing visceral artery aneurysms, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) remains the gold standard and is also used for treatment. Computed tomography (CT) imaging has a sensitivity of 67%, while ultrasound has a sensitivity of 50% [2]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast has a similar sensitivity to contrast-enhanced MRI and is an alternative to CT in cases of pregnancy, renal insufficiency, or contrast allergy [3]. When a visceral artery aneurysm rupture is suspected, CT imaging is the preferred diagnostic method [3]. However, a 2020 study by Vittoria et al. reported that 58% of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms were missed on CT scans, regardless of location or rupture status. The main reasons were the absence of arterial phase imaging, metal artifacts, and diagnostic oversight.

Regarding the treatment of gastroduodenal artery aneurysms, intervention is recommended in all cases if the risks of the procedure are within acceptable limits. The choice between endovascular intervention and surgery depends on several factors, including the patient's hemodynamic status, the presence of abdominal infection, and the aneurysm's location and morphology. Endovascular intervention is generally the preferred method, regardless of whether the aneurysm has ruptured, with a success rate exceeding 90%. One of the long-term complications of endovascular treatment is aneurysm recanalization, which occurs in 9-15% of cases, making postprocedural follow-up essential. Follow-up can be conducted using CT imaging, although there is a risk of artifacts from the devices used, which highlights the potential role of MRI and ultrasound. Currently, there are no clear guidelines regarding the duration of follow-up after intervention.

Conclusion

Although not a common cause, the rupture of a gastroduodenal artery aneurysm is a highly fatal condition in pediatric patients. This underscores the critical importance of accurately identifying and describing aneurysms through initial imaging modalities, with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) in the arterial phase being particularly valuable. Depending on the clinical scenario and the vascular anatomy involved, treatment options may include surgical intervention or endovascular procedures, with the latter being the preferred approach in most cases.

Patient consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. All patient details have been anonymized to protect privacy.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Cox K, Ament ME. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1979;63(3):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habib N, Hassan S, Abdou R, Torbey E, Alkaied H, Maniatis T, et al. Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm, diagnosis, clinical presentation and management: a concise review. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaer RA, Abularrage CJ, Coleman DM, Eslami MH, Kashyap VS, Rockman C, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on the management of visceral aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(1S):3S–39S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owensby S, Taylor K, Wilkins T. Diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(1):134–145. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.01.140153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lirio RA. Management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children: variceal and nonvariceal. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2016;26(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pham Vo Phuong T, Phan Thi Minh T, Mai The D. Clinical characteristics and causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in children. J Med Pharm. 2022:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shawky MS, Tan J, French R. Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm: a case report and concise review of literature. Ann Vasc Dis. 2015;8(4):331–333. doi: 10.3400/avd.cr.15-00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris K, Chalhoub M, Koirala A. Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm rupture in hospitalized patients: an overlooked diagnosis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2(9):291–294. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i9.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarin M, Ali S, Majid A, Jan Z. Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm - post traumatic pancreatic pseudocyst drainage - an interesting case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;42:82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kavitha TK, Madabhavi P, Takia L, Awasthi P, Chaluvashetty SB, Aneja A, et al. Life-threatening upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to ruptured gastroduodenal artery aneurysm in a child. JPGN Rep. 2020;2(1) doi: 10.1097/PG9.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]