Abstract

Most patients with head and neck cancers struggle with their treatment, particularly those with recurrent cancer. However, there is no consensus on effective treatments for recurrent head and neck cancer. Recurrent cases are often challenging to treat because performing both reirradiation and surgical intervention can occasionally be difficult.

This report describes the effective cisplatin intra-arterial chemotherapy with oral S-1 for a recurrent case of maxillary gingival cancer (rT4bN1M0, rStage ⅣB). The patient who had undergone chemoradiotherapy 13 years ago and achieved complete response (CR) was referred to us due to recurrence. His recurrent lesions were located on the left maxillary bone, and a metastatic cervical lymph node was detected. We approached the feeder of the locoregional recurrence site using Seldinger's technique and repeated the cisplatin intra-arterial chemotherapy 5 times. As a result, we achieved a complete response, including the regional metastatic lymph node, without radiation or surgery. Notably, although we infused the anticancer drug into the feeder of the locoregional metastatic area, we noticed its effect on the metastatic cervical lymph node. Initially, neck dissection following intra-arterial chemotherapy had been planned; however, owing to the high effectiveness of the treatment, the subsequent surgery was deemed unnecessary. No evidence of recurrence has been observed during the 2.5-year follow-up period. In the future, intra-arterial chemotherapy can be an alternative option for patients with recurrent head and neck cancers, and our result seems to be enough to indicate that possibility.

Keywords: Intra-arterial chemotherapy, Head and neck cancer, Recurrence, Lymph node metastasis, Seldinger's method

Introduction

Recently, an increasing number of young people have been diagnosed with head and neck cancer, and 40% of patients are reportedly experiencing recurrence [1]. Conventionally, surgery is the first choice for the treatment of recurrent head and neck cancer. However, it is occasionally considered unfeasible due to the patient's condition or from the functional standpoint; such cases often require a stern determination in choosing the treatment strategy [1]. Furthermore, reirradiation after salvage surgery reportedly does not improve overall survival despite the higher toxicities (e.g. osteoradionecrosis, fistulas, and major vessel necrosis or rupture), although it enhances locoregional control and disease-free survival [2]. In addition, chemoradiotherapy can cause systemic toxicity, leading to the damage of other organs. The new treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is effective for the limited case, although these can be expected a high rate of sustained response [3]. Thus, while exploring an alternative strategy for recurrent head and neck cancer, we experienced a case of recurrent maxillary gingival cancer wherein complete response (CR) was achieved without radiation or surgery. The patient required only trans-arterial cisplatin infusion with oral S-1 administration to obtain this outcome. Herein, we describe our strategy emphasizing trans-arterial infusion and discuss probable factors contributing to the favorable result.

Case

A 76-year-old man with recurrent maxillary gingival cancer was referred to our department for intra-arterial chemotherapy. He had undergone chemoradiotherapy 13 years ago at our institution. At that time, the patient received chemoradiotherapy, which included 4 intravenous cisplatin infusions. The total amount of cisplatin administered in 4 infusions was 140 mg, and the total dose of conventional X-ray therapy was 40 Gy. Furthermore, he had taken oral S-1 concurrently. In addition, a super-selective trans-arterial infusion was performed with 50mg of cisplatin. As a result, he achieved CR without any surgery, although neck dissection was initially considered. After the treatment, he was followed up regularly until he noticed his cervical lymph nodes were swelling 13 years later.

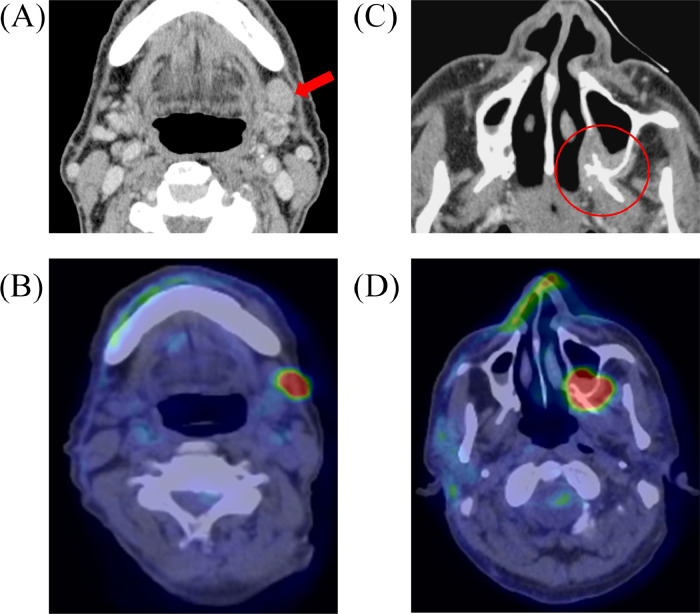

The recurrence was subsequently visualized via computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and 2-deoxy-2-[18F] fluoro glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT). These imaging inspections revealed that the left submandibular node was swollen (16 × 11 mm); therefore, metastasis was diagnosed (Fig. 1A, B). In addition, a recurrent lesion on the left maxillary bone was suspected (Figs. 1C, and D). A biopsy of the recurrent lesion confirmed that it was poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, matching the pathology of the primary site treated 13 years ago (rT4bN1M0, rStage ⅣB). The biopsy showed no evidence of perineural invasion and angiolymphatic invasion.

Fig. 1.

CE-CT (A and C) and FDG-PET/CT (B and D) reveal the locoregional recurrence (red circle) and a cervical lymph node metastasis (red arrow).

We planned intra-arterial infusion of cisplatin to the recurrent lesion with the concurrent intake of S-1(tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil potassium). Neck dissection was also scheduled after intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy completion to control the metastatic cervical lymph node.

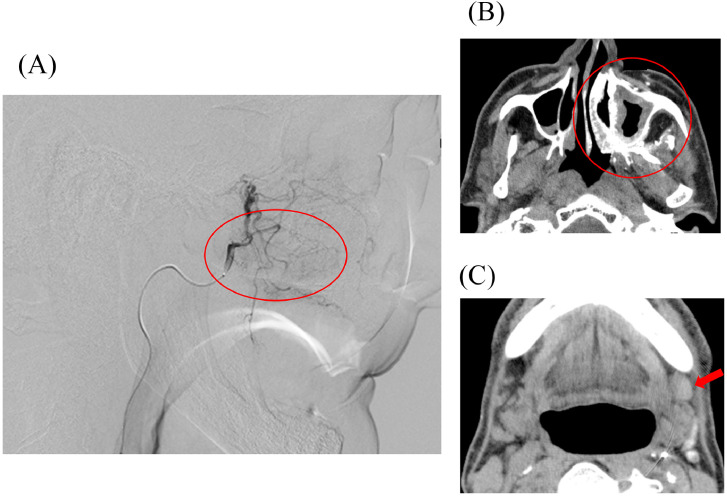

We approached the target vessel via a femoral artery using Seldinger's technique in all 5 treatments. Simultaneously, an appropriate amount of sodium thiosulfate was administered intravenously for neutralization. Furthermore, we infused an appropriate amount of heparin intravenously before advancing the guidewire and catheter over a left common carotid artery to avoid thromboembolic complications. After catheterization, we confirmed the feeding area and perfusion on the tumor using digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and angiographic CT (CTA) before infusing cisplatin (Fig. 2). This procedure for the recurrent lesion was conducted 5 times in 3 to 4-week intervals. The lesion was supplied entirely or near entirely by the ipsilateral maxillary artery, including the accessory meningeal artery, and a total dose of infused cisplatin was approximately 635 mg in 5 treatments. Although we attempted a super-selective infusion to the accessory meningeal artery during the second treatment, we had to change the plan due to the emergence of tinnitus after infusing 15 mg of cisplatin. In the present case, the accessory meningeal artery diverged from the middle meningeal artery, which may have caused a small amount of cisplatin infusion to flow to the middle meningeal artery through backflow and causing tinnitus. As another possibility, we wedged the catheter at the vessel, and the narrow diameter may have contributed to the onset of tinnitus in the patient. Although we could not determine the cause, we confirmed that the patient's tinnitus disappeared spontaneously after discontinuing the injection. As a result, all remaining cisplatin was administered to the ipsilateral maxillary artery. The dose of S-1 was 100 mg per day, and its administration was initiated 9 days before the first round of intra-arterial chemotherapy and continued until approximately 7 weeks after its completion.

Fig. 2.

Those images are obtained during the first treatment of intra-arterial cisplatin infusion. The image of DSA (A) showed a tumor staining through the left maxillary artery (red circle), and the images of CTA on recurrent area (red circle) and a metastatic lymph node (red arrow), respectively (B and C).

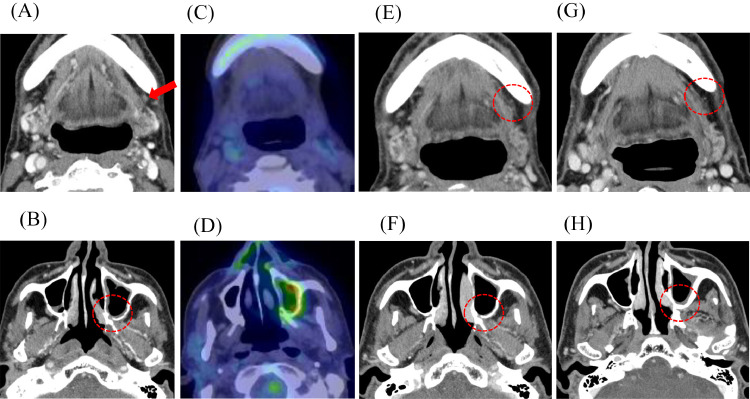

The follow-up CT of the second intra-arterial chemotherapy revealed the diminution of metastatic left submandibular node concurrently with the reduction of recurrent tumor volume, although cisplatin was administered directly to only the recurrent lesion. The lymph node was decreased from 16 × 11 mm to 4 × 3 mm (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the uptake on both locoregional lesions and the lymph node disappeared on FDG-PT/CT around the same time (Figs. 3C and D). The follow-up was scheduled 4 weeks after all scheduled treatments were completed, and further therapy efficacy in the recurrent lesion and lymph node was conducted using CT (Figs. 3E and F), MRI, FDG-PET/CT, and ultrasound. The lymph node was decreased in size and scarred (Fig. 3E). Consequently, the patient was obtaining CR and could avoid following the planned neck dissection. No serious adverse events were associated with this method throughout the treatment period. Afterward, the patient underwent regular follow-ups and was monitored every month for recurrence in the first year and every 3 months since the second year. No evidence of recurrence has been identified in the two-and-a-half-year follow-up period until now (Figs. 3E-H).

Fig. 3.

A-D Those are the images of CECT (A and B) and FDG-PET/CT (C and D) obtained around 2 weeks after the second treatment.

Fig. 3E-H Those are the CECT images after the treatment; (E) and (F) are around 3 months after, and (G) and (H) are around 2 years and 3 months after the trans-arterial cisplatin infusion was completed. There is no evidence of recurrence in both images.

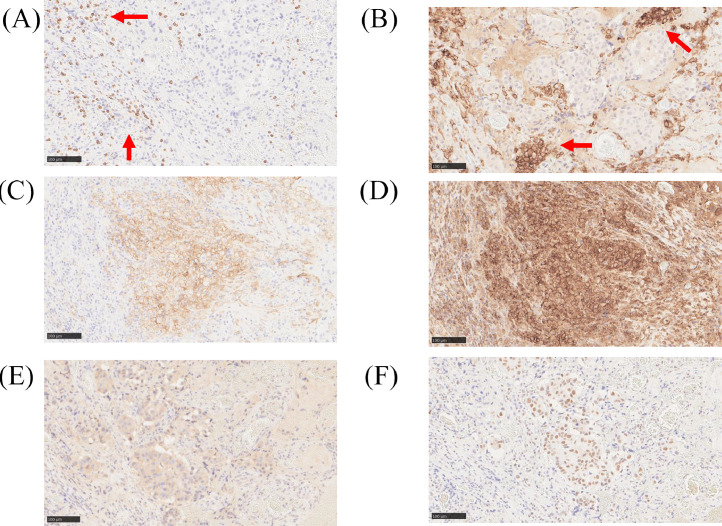

Pre-treatment biopsy specimens of recurrent tumors were examined for CD8 (dilution 1:100, C8/144B; Dako, Denmark), CD11c (dilution 1:800, 2F1C10; proteintech, USA), PD-L1 (dilution 1:100 SP142; Ventana, USA), HLA-1 (dilution 1:2000, EMR8-5; Hokudo, Japan), Calretculin (dilution 1:1000, ab92516; abcam, UK), and HMGB1 antibody (dilution 1:1000, ab18256; abcam, UK) are shown in Fig. 4. Infiltration of peritumoral cells positive for CD8, a marker for cytotoxic T cells, and CD11c, a marker for dendritic cells, was observed (Figs. 4A and B). In addition, higher expression of HLA class 1, which is involved in antigen-presenting ability, and PD-L1, associated with immune checkpoint, were observed on the tumor surface (Figs. 4C and D). Furthermore, intracellular expression of Calreticulin and HMGB1, known to be expressed upon immunogenic cell death, was observed (Figs. 4E and F).

Fig. 4.

Images of immunostaining for several antibodies. CD8-positive cells infiltrate around the tumor cells (A; red arrow); CD11c-positive dendritic cells aggregate and localize around the tumor (B; red arrow). Higher expression of PD-L1 and HLA class 1 on the surface of the tumor cells (C and D). Calreticulin staining in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells (E). HMGB1 staining in the nucleus of the tumor cells (F). Horizontal bars represent 100μm.

Discussion

Recently, the number of people diagnosed with head and neck cancer has increased, including the younger generation, and nearly 40% patients after definitive treatment will experience a recurrence [1]. Recurrent cancer is a significant contributor to cancer-related mortality. The cases deemed operable are considered salvage surgery; however, curative-intent surgery for recurrent head and neck cancer is not always feasible and carries a high risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality [2]. In our current case, due to the site of the lesion around the maxillary sinus, there were further challenges in considering the invasiveness of the operation and the significant reduction in the patient's quality of life in determining the treatment strategy. Furthermore, reirradiation for recurrent lesions also has risks for late toxicities.

Other than surgery or radiation, various alternative therapies, including anticancer drugs, molecular-targeted drugs, PD-1-inhibiting antibodies, and so forth, were explored for recurrent head and neck cancers worldwide [2,4]. However, the standard treatment for these is yet to be established.

We could achieve CR by trans-arterial infusion of cisplatin with concurrent oral S-1, which allowed the patient to avoid the neck dissection initially planned. It is noted that radiotherapy was absent throughout the treatment for recurrence. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the efficacy of intra-arterial infusion of cisplatin with head and neck cancer patients for metastatic cervical lymph nodes without the need for surgical operation or radiotherapy.

Our successful outcome can be related to the possibility of the efficacy of cisplatin for lymph node metastasis, which had been achieved without selective administration. Herein, we observed a reduction in metastatic lymph nodes, even though we did not directly infuse cisplatin into feeders and CTA during the treatment revealed the absence of contrast agent staining. Although the mechanism is not yet clear, some reports suggest that cisplatin infused into the primary tumor through the intra-arterial route also impacts the lymph nodes [5]. The speculation arises from the idea that cisplatin injected into the primary site, could potentially pass into the lymph nodes via lymphatic flow [6,7]. A previous report on intra-arterial cisplatin infusion in tongue cancer found significant differences in platinum concentration between sentinel and nonsentinel lymph nodes in 5 cases involving sentinel node biopsy and elective neck dissection. These 5 cases were all injected cisplatin only to the primary site [6]. Moreover, the development of lymph node metastases is said to be caused by entering the cells into the surrounding tissues and lymphatic network from the primary tumor [8]. Considering this perspective, the site of lymph node metastasis existing on the same side may have been advantageous, assuming the network was between the primary site and the lymph node metastasis and the drug was delivered to surrounding tissues, including the lymph node.

Furthermore, Sakashita et al. compared the effectiveness of RADPLAT with and without the infusion to cervical lymph nodes in their study of 65 patients with head and neck cancer, and their results revealed no significant difference in 5-year-nodal control rates between the 2 groups [9]. This may confirm our hypothesis that cisplatin passes through the lymph nodes via lymphatic flow and enable us to interpret that we only have to administer cisplatin to the primary sites, even in cases of lymph node metastases.

In our case, a biopsy of the recurrent tumor was obtained and immunostaining was used to examine factors related to tumor immunity, which were shown to be highly expressed (Fig. 4). One possible explanation for the favorable results of intra-arterial administration of CDDP is that CDDP induces immunogenic cell death (ICD) of the tumor, which may generate the so-called abscopal effect [10] and could suppress adjacent untreated regional lymph node metastases. ICD has also been reported to be induced by CDDP [11], suggesting that tumor-specific antigens released from tumors and danger signals such as calreticulin and HMGB1 activate dendritic cells and macrophages, which in turn activate cytotoxic T cells that recognize the tumor-specific antigens. The activated cytotoxic T cells recognizing the tumor-specific neoantigens may attack the tumor cells [12].

As another factor, we should consider the effectiveness of S-1. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) are often administered S-1 as concurrent therapy with radiation, and so forth in Japan. Matsuki et al. reported administering S-1 to patients waiting for operations to suppress tumor growth and achieve a high nongrowth rate of primary lesions and lymph node metastases [13], although doubts regarding the effectiveness of S-1 have been prevalent to date [14]. Moreover, a report investigating the efficacy of S-1 and cisplatin as a palliative treatment in recurrent or metastatic SCCHN reported that only 4.1% of patients achieved CR [15]. Another report describes the combination of S-1 and cisplatin, which seems feasible; however, it is used as an induction treatment before definitive local treatment [16]. These reports deem the efficacy of the combination of S-1 and cisplatin limited, and it can be considered insufficient to achieve a synergistic effect enough to control both the locoregional site and the metastatic lymph node in the present case. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that trans-arterial chemotherapy significantly contributed to the successful outcome while acknowledging the current limitation of this singular case.

Some favorable conditions may have helped this case, and similar cases are not commonly expected. However, on the other hand, the predominant histological subtype of head and neck cancer is SCC [3], which is the same as our case. This implies that our strategy may be adapted not only for maxillary gingival cancer but also for various primary sites. So as to validate and substantiate the effectiveness of this method across a broader spectrum of patients, it is necessary to investigate the method to triage the cases amenable to trans-arterial chemotherapy without radiotherapy. Although it seems challenging to accumulate a large number of cases similar to ours absented radiation or surgery, we may find some factors amenable to the present strategy by examining cisplatin sensitivity or prognosis of the patients with the treatments of combination trans-arterial chemotherapy and other therapies retrospectively. Among them, when specific factors are revealed, our case brings new option for the treatment of recurrent head and neck cancer, particularly with lymph node metastases, having challenges in reirradiation or surgery.

Conclusion

Intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy can be a promising strategy for recurrent head and neck cancer, provided it is performed under suitable conditions. Moreover, it may be effective for metastatic lymph nodes even without concurrent radiotherapy, which may help avoid invasive surgery or high-risk reirradiation, although several issues need to be clarified and standardized for it to be considered a treatment option.

Patient consent

We obtained written informed consent from the patient to publish this case report.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Zhang S, Zeng N, Yang J, He J, Zhu F, Liao W, et al. Advancements of radiotherapy for recurrent head and neck cancer in modern era. Radiat Oncol. 2023;18(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s13014-023-02342-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaikh H, Karivedu V, Wise-Draper TM. Managing recurrent metastatic head and neck cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2021;35(5):1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Wang R, Fang J. Exploring the frontiers: tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Discover Oncol. 2024;15(1):22. doi: 10.1007/s12672-024-00870-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Kioi M, Hayashi Y, Koizumi T, Koike I, Yamanaka S, et al. Efficacy of concurrent chemoradiotherapy with retrograde super selective intra-arterial infusion combined with cetuximab for synchronous multifocal oral squamous cell carcinomas. Radiat Oncol. 2023;18(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13014-023-02282-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koike K, Ohashi N, Nishiyama K, Okamoto J, Sasaki T, Ogi K, et al. Clinical and histopathologic effects of neoadjuvant intra-arterial chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin in combination with oral S-1 on StageⅢ and Ⅳ oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2022;134(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2022.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakashita T, Homma A, Oridate N, Suzuki S, Hatakeyama H, Kano S, et al. Platinum concentration in sentinel lymph nodes after preoperative intra-arterial cisplatin chemotherapy targeting primary tongue cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132(10):1121–1125. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.680494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kano S, Suzuki T, Yoshida D, Tsushima N, Hamada S, Yasuda K, et al. The superselective intra-arterial infusion of cisplatin and concomitant radiotherapy (RADPLAT) is effective for metastatic lymph nodes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2023;28(9):1121–1128. doi: 10.1007/s10147-023-02363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukumura R, Sukhbaatar A, Mishra R, Sakamoto M, Mori S, Kodama T. Study of the physicochemical properties of drugs suitable for administration using a lymphatic drug delivery system. Cancer Science. 2021;112(5):1735–1745. doi: 10.1111/cas.14867.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakashita T, Homma A, Oridate N, Hatakeyama H, Kano S, Mizumachi T, et al. Evaluation of nodal response after intra-arterial chemoradiation for node-positive head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(6):1671–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pevzner AM, Tsyganov MM, Ibragimova MK, Litvyakov NV. Abscopal effect in the radio and immunotherapy. Radiat Oncol J. 2021;39(4):247–253. doi: 10.3857/roj.2021.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie KP, Pirnie R, Mesaros C, Blair IA. Cisplatin dependent secretion of immunomodulatory high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein from lung cancer cells. Biomolecules. 2023;13(9):1335. doi: 10.3390/biom13091335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellman I, Chen DS, Powles T, Turley SJ. The cancer-immunity cycle: Indication, genotype, and immunotype. Immunity. 2023;56(10):2188–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuki T, Fushimi C, Miyamoto S, Takahashi H, Masubuchi T, Tada Y, et al. Preoperative S-1 therapy for head and neck carcinoma during the waiting period before surgery. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(6):3177–3183. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sano D, Tanabe T, Kubota A, Miyamoto S, Tanigaki Y, Okami K, et al. Addition of S-1 to radiotherapy for treatment of T2N0 glottic cancer: results of the multiple-center retrospective cohort study in Japan with a propensity score analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019;99 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HS, Kim HR, Kim GM, Kim HS, Koh YW, Kim SH, et al. The efficacy and toxicity of S-1 and cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 2012;70(4):539–546. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1933-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon DH, Kim SB. S-1 plus cisplatin: another option in the treatment of advanced head and neck cancer? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10(5):659–662. doi: 10.1586/era.10.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]