Abstract

ALK5 inhibitors represent an attractive therapeutic approach for the treatment of a variety of pathologies, including cancer and fibrosis. Herein, we report the design and in vitro characterization of a novel series of ALK5 modulators featuring a 4,6-disubstituted pyridazine core. A knowledge-based scaffold-hopping exploration was initially conducted on a restricted set of heteroaromatic cores using available ligand- and structure-based information. The most potent structurally novel hit compound 2A was subsequently subjected to a preliminary optimization for the inhaled delivery, applying physicochemical criteria aimed at minimizing systemic exposure to limit the risk of adverse side effects. The resulting inhibitors showed a marked boost in potency against ALK5 and in vitro ADME properties, potentially favoring lung retention. The optimized hits 20 and 23 might thus be considered promising starting points for the development of novel inhaled ALK5 inhibitors.

Keywords: ALK5 inhibitors, TGF-β, knowledge based, inhaled delivery, fibrosis

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a pleiotropic cytokine belonging to a superfamily of three isoforms TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3. They all signal through transmembrane serine/threonine kinase receptors, the type 1, TGF-βR1 or activin-like kinase 5 (ALK5) receptor, and type 2, TGF-βR2. Indeed, TGF-β binds to the TGF-βR2 homodimer, which in turn recruits two units of ALK5, activating the receptor by phosphorylation at the glycine–serine rich (GS) domain. Upon activation, ALK5 phosphorylates its cytoplasmatic substrates Smad2/Smad3, which form a complex with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus, affecting the corresponding gene transcription.1−3

TGF-β signaling plays a critical role in the regulation of many biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation and development, tissue homeostasis, and immune response.

Signaling overexpression or dysregulation is implicated in multiple disease conditions, such as cancer and fibrosis,4−7 making pharmacological modulation of this pathway an attractive therapeutic approach. Pathway druggability encompasses diverse modalities including TGF-β traps, mAb, ASO, siRNA, and small molecules.8−12 Several small-molecule inhibitors targeting the ATP binding site have been developed over the years by companies and institutions.13

Thus far, only a few ALK5 inhibitors have progressed to clinical development. Galunisertib (LY2157299), LY3200882, Vactosertib (EW7197), GFH-018, and YL-13027 (Figure 1) are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for oncology indications.14−19 More recently, two ALK5 small-molecule inhibitors approached the clinic with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) as an indication. Theravance TD-1058, the first-in-class ALK5 inhibitor to enter phase I for IPF,20 was discontinued in 2021 for business reasons. In December 2023, Agomab AGMB-447 started phase I trial with the same indication.21 These two small-molecule inhibitors are optimized for inhaled delivery, enabling favorable TGF-β modulation in the lung while minimizing toxicity effects driven by systemic exposure of oral ALK5 inhibitors.22

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of representative ALK5 inhibitors in the clinic.

With this basis, we embarked on a program to identify novel ALK5 small-molecule inhibitors for the inhaled treatment of lung fibrosis. The rational design of novel molecular scaffolds was followed by the preliminary optimization driven by “inhalation-by-design” criteria.23 The most advanced compounds were profiled for their in vitro ADME properties in view of further optimization to yield inhaled ALK5 inhibitors.

Given the wide range of structurally different ALK5 inhibitors reported in the scientific literature as well as the availability of a significant number of inhibitor-bound X-ray structures,24 the search for novel chemical scaffolds took advantage of a knowledge-based approach, in which ligand- and structure-based information were combined together to rapidly and rationally design new compound series. A preliminary analysis of literature and structural information revealed that the majority of ALK5 inhibitors incorporated three pharmacophoric features (Figure 2): (i) the selectivity substituent (orange sphere), usually represented by pyridyl or phenyl moieties, accommodated in a highly lipophilic pocket close to the gatekeeper residue (Ser280); (ii) the hinge-binding group (blue sphere), forming key hydrogen-bond (HB) interactions with the backbone of His283; and (iii) the central core (green sphere), usually represented by a mono- or bicyclic aromatic system, involved in key polar interactions with the side chain of the catalytic lysine (Lys232) or/and with a conserved water cluster known to play a crucial role in isoform selectivity.25 Finally, the core fragment and hinge binder can be connected through a small linker group (X in Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Superposition of the co-crystallized ALK5 inhibitor complexes 1PY5 (yellow carbons) and 3HMM (green carbons). Important pharmacophoric features are represented as transparent spheres while key kinase–ligand HB interactions are depicted with dashed black lines. (B) Schematic representation of a prototypic ALK5 inhibitor. (C) Two representative ALK5 inhibitors extracted from refs (27) and (28) (PDB ID: 3HMM). The HB acceptor group on the hinge-binding group is highlighted in red.

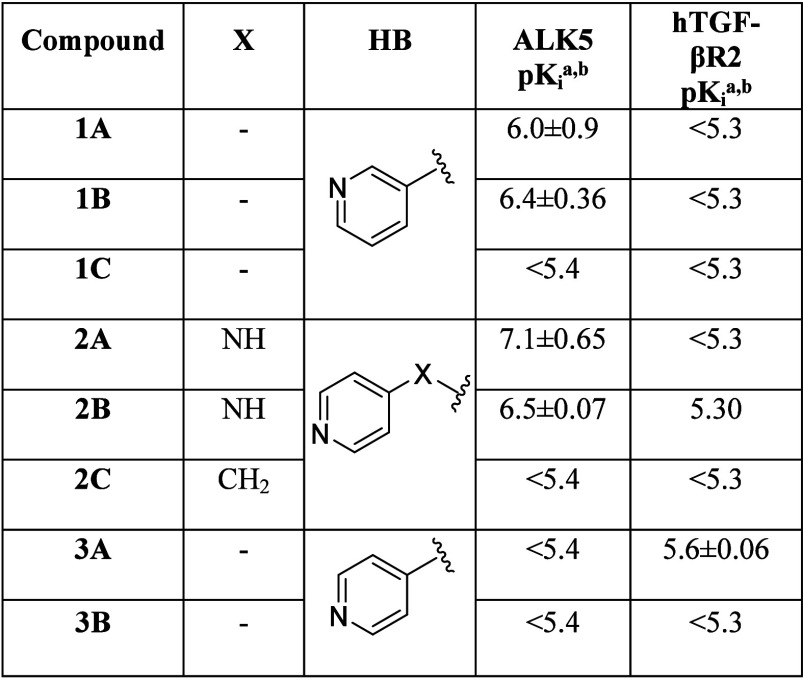

To retain the hypothesized ALK5 pharmacophore model, three novel monocyclic heteroaromatic cores were selected for a preliminary exploration (Table 1). The new cores were designed to explore different patterns of HB-capable functions making key interactions with residues at the edge of the ATP-binding cavity. Indeed, while the pyridazine core A bears two adjacent HB acceptors that could potentially interact with the catalytic lysine, the two pyrazinone regioisomers B and C were decorated with a carbonyl group designed to be either in proximity of the catalytic lysine (B) or directed toward the rim of the ATP-binding cleft (C).

Table 1. Central Cores Exploration.

Potency values are reported as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation from at least two independent experiments.

All data were obtained using an enzymatic assay with purified kinase domain of ALK5 or TGF-βR2 in the presence of ATP at its Km for each enzyme. Inhibition of enzymatic activity was measured using ADP-Glo kit (Promega). The Ki values were calculated from IC50 using the Cheng and Prusoff equation.29

Different hinge-binding motifs, extracted from public ALK5 inhibitors, were installed on the three selected core structures, keeping the 5-chloro-2-fluorophenyl fragment, widely applied as the selectivity substituent in many chemical classes of ALK5 modulators,26 fixed. An in-depth analysis of literature compounds highlighted the presence of different hinge-binding groups branching from 6-membered core rings (Figure 2C). When the scaffold and the hinge binder were directly connected, the latter motif was characterized by an HB acceptor in the meta position (e.g., 3-pyridyl);27 conversely, if the two fragments were connected through a linking atom, the hinge-binding moiety usually included an HB acceptor in the para position (e.g., 4-pyridyl).28 Accordingly, the selected scaffolds were functionalized using either a 3-pyridyl ring directly connected to the central core (series 1) or a 4-pyridyl system connected to the core fragment through a linking atom (series 2).

While 1A and 1B, which bear a 3-pyridyl hinge binder directly attached to the core, exhibited micromolar potencies against ALK5 receptor kinase, derivative 1C showed a dramatic drop in pKi. This could be due, at least in part, to the presence of the carbonyl function next to the aromatic hinge binder, which might induce ligand structural distortions, hampering the formation of proper interactions with the hinge region. Moreover, the carbonyl oxygen of compound 1C pointed toward the rim of the ATP-binding cavity, and therefore might not be able to form strong polar interactions with the catalytic lysine located at the inner side of the kinase active site. To investigate the presence of conformational strains in the kinase-bound geometry of 1C, ligand structures extracted from MD simulations conducted on the 1C–ALK5 complex were compared to those collected during metadynamic simulations of the same compound in a pure solvent. Intriguingly, the bound-state geometry of 1C corresponded to a minimum-energy configuration in solution (torsional strain = 0.10–0.66 kcal/mol, Figure S2), suggesting that the presence of the carbonyl function on the core of 1C did not alter the ability of the compound to assume a binding-competent arrangement. Conversely, free energy perturbations (FEPs) consistently predicted a loss in potency when shifting from 1A (ΔΔG = 0.79 ± 0.07 kcal/mol) or 1B (ΔΔG = 1.26 ± 0.18 kcal/mol) to 1C, in line with experimental results (ΔΔG > 0.82 kcal/mol and ΔΔG > 1.36 kcal/mol, respectively). FEP simulations clearly showed that 1C formed weak interactions with the catalytic lysine as well as with residues delimiting the ATP-binding cavity, likely indicating that the negligible pKi of 1C was not due to a perturbation of its conformational equilibrium but rather due to a remarkable weakening of key kinase–ligand interactions. FEP calculations also showed that while 1B was able to form direct polar contacts with the side chain of Lys232 via its endocyclic carbonyl function, 1A interacted with the same residue through an extended network of water-mediated contacts. The introduction of a linking group between the core and the hinge-binding motif greatly affected the potency toward ALK5 only for core A. Indeed, 2A showed a 10-fold increase in pKi compared to 1A, reaching a potency in the high nanomolar range.

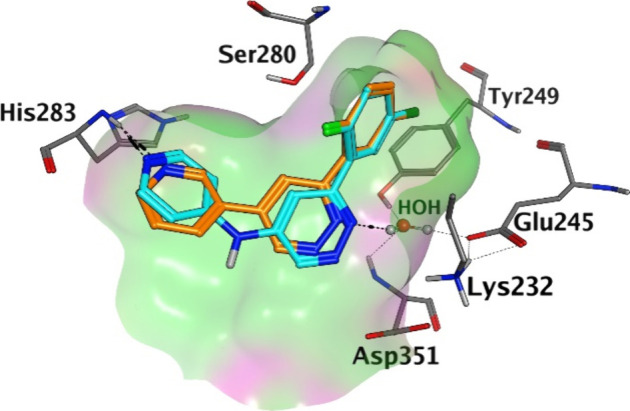

We speculated that the NH spacer could give a general better occupation of the binding site, strengthening the HBs with the hinge as well as with the bridging water molecule and consolidating the positioning of the 5-chloro-2-fluorophenyl group in the selectivity pocket (Figure 3). Conversely, 2B showed a potency comparable to that of its analogue 1B, suggesting that core B might be less suitable for structural modifications. The introduction of the NH linker may have shifted the core structure, leading to the formation of unfavorable interactions between the endocyclic carbonyl function and the neighboring catalytic residue. To better investigate the effect brought by the introduction of the bridging NH function at a molecular level, MD simulations were conducted on 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B (see the Supporting Information). While derivative 2A formed a higher number of direct HB interactions with the protonated side chain of Lys232 as well as with the hinge region compared to 1A (Table S1), the percentage of snapshots forming an HB contact with the catalytic lysine as well as with His283 was comparable between 1B and 2B (Table S1), rationalizing, on one hand, the higher potency of 1B and 2A with respect to 1A, and on the other hand, the similar pKi values exhibited by 1B and 2B. The same conclusions could be drawn for core C, where the introduction of a linking atom, although different from NH, did not alter the potency (2C vs 1C). Notably, while the negligible potency of 1C was mainly ascribed to the lack of strong polar interactions between the ligand core and the inner portion of the active site, the lack of activity observed for 2C seemed to be due, at least in part, to a conformational effect. Indeed, ligand conformations extracted from MD simulations of the 2C–ALK5 complex did not reside in minimum-energy regions of free energy surfaces reconstructed via metadynamics simulations conducted on 2C in pure solvent (torsional strain = 2–3 kcal/mol, Figure S2), likely indicating that the methylene linker hampered the rearrangement of the ligand molecule in a binding-competent geometry.

Figure 3.

1A (orange C atoms) and 2A (cyan C atoms) binding modes predicted by docking simulations.

Structure–activity relationships (SARs) retrieved from literature as well as preliminary modeling studies (Figure S1) clearly indicated that a 4-pyridyl hinge binder directly connected to a 6-membered core fragment should not be tolerated, probably due to the formation of suboptimal HB interactions with the hinge region. Accordingly, 3A and 3B, with a 6-membered ring scaffold directly attached to a 4-pyridyl substituent, showed a dramatic drop in potency.

Additionally, all newly designed compounds were inactive or weakly active at hTGF-βR2 (Table 1).

Taken together, these results prompted the selection of 2A as a starting point for subsequent exploration. The following round of optimization was aimed at increasing biochemical potency while identifying the best exit vectors that could be further functionalized following an “inhalation-by-design” strategy. To this end, substituents able to form additional HB interactions or to strengthen the existing one with His283 were introduced in position 2 or 3 of the pyridine hinge binder (Table 2).

Table 2. Hinge Binder Exploration in the Pyridazine Core.

| compound | R | ALK5 pKia |

|---|---|---|

| 2A | – | 7.1 ± 0.65 |

| 4 | 2-NH2 | 8.5 ± 0.10 |

| 5 | 3-NH2 | 7.3 ± 0.24 |

| 6 | 2-CONH2 | 6.5 ± 0.02 |

| 7 | 3-CONH2 | 8.3 ± 0.27 |

| 8 | 2-OMe | 6.1 ± 0.09 |

| 9 | 3-OMe | 7.8 ± 0.09 |

The 2-amino-pyridine 4 showed a 25-fold increase in potency, while the 3-amino analogue 5, although tolerated, proved to have no beneficial effects on ALK5 activity. These results are in line with the formation of an HB interaction, where the C=O of the His283 is recruited in a second HB, as exemplified in our model of binding mode of 4 (Figure 4A). The substitution of the 2-amino group of 4 with an amide fragment (6) led to a 100-fold decrease in potency. This dramatic decrease was initially rationalized by docking simulations, which showed compound 6 close to the rim of the ATP-binding site and a concomitant weakening of polar interactions with the hinge region (Figure 4A). Conversely, the corresponding amide-decorated isomer (compound 7) exhibited a pKi of 8.3, which is slightly lower than that observed for 4. The results of docking calculations suggested that the striking difference between regioisomers 6 and 7 could be ascribed, at least in part, to a favorable reduction of the entropic penalty in the latter derivative. Indeed, the amide oxygen of compound 7 can form an intramolecular HB with the spacer NH, allowing a preorganization of the ligand molecule into the putative bioactive conformation (Figure 4B). FEP calculations were then applied to model the transition between compounds 7 and 6 at a molecular level, providing useful insights that could better rationalize the different potency values. The transformation from the 3-amido analogue to the 2-amido one was consistently predicted as unfavorable from FEP simulations, with a calculated relative free energy change (ΔΔG = 1.17 ± 0.10 kcal/mol) in fair agreement with the experimental one (ΔΔG = 2.46 kcal/mol). A visual inspection of FEP trajectories clearly showed that, although the 2-amido group is able to form a stable, water-mediated interaction with the side chain of Asp290 (Figure S3) as well as an HB interaction between the amide NH2 group and the backbone carbonyl of His283, the steric hindrance of the amide function caused an inward rotation of the ligand toward the inner portion of the kinase active site, significantly weakening the HB interaction between the ligand pyridine nitrogen and the hinge region (Figure S3).

Figure 4.

(A) Compound 4 (magenta C atoms) and 6 (yellow C atoms) binding modes predicted by docking simulations. (B) Compound 7 (cyan C atoms) binding mode predicted by docking simulations.

The crucial role of an HB donor function at position 2 of the pyridine hinge binder was confirmed by the introduction of a 2-methoxy substituent (8). Indeed, the inability of such substituent to form an additional HB with the hinge region as well as the presence of potential unfavorable Coulombic interactions with the His283 backbone carbonyl led to a 10-fold and >100-fold decrease in potency compared to the unsubstituted and the 2-amino derivatives, respectively. Consistently, the relocation of the methoxy group to position 3 (9) resulted in a significant increase (∼50-fold) in ALK5 potency, which could be explained by the formation of a favorable intramolecular HB interaction between the methoxy substituent and the NH linker, leading to a preorganization of the ligand structure into a bioactive conformation.

Next, we decided to explore in detail the selectivity portion of the molecule, using 4 as the reference derivative because of its high cell-free potency. Given the limited size of the ALK5 selectivity pocket, we designed a focused library by varying the substitution pattern of the phenyl group as well as potential bioisosteric replacements of this moiety (e.g., pyridine and thiophene derivatives).

It appeared that the SAR of the selectivity group was quite flat (Table 3), with 5-chloro-2-fluorophenyl standing out as the best performing substituent.

Table 3. Selectivity Substituent Exploration.

In light of these results, 4 was used as a starting point of further derivatization suitable for inhaled delivery. First, the cell-based potency and ADME profile of 4 were assessed (Table 4). When tested, compound 4 inhibited ALK5-mediated phosphorylation of the Smad2 protein in a human epithelial cell line (hA549 cells) with a >100-fold drop in potency compared to its biochemical activity (pIC50 = 6.05), exhibiting low solubility, medium permeability in Caco2 cells, and low clearance in human liver microsomes.

Table 4. Profiles of Compounds 4 and 19–24.

Potency values are reported as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation from at least two independent experiments.

All data were obtained using an enzymatic assay with purified kinase domain of ALK5 or TGF-βR2 in the presence of ATP at its Km for each enzyme. Inhibition of enzymatic activity was measured using an ADP-Glo kit (Promega). The Ki values were calculated from IC50 using the Cheng and Prusoff equation.

Cellular pIC50 values were obtained by measuring pSMAD2 levels in A549 cells stimulated for 1 h with 0.3 nM TGF-β1 with or without test compounds;

Lipophilicity and pKa were calculated using Chem Axon.

Solubility was evaluated from DMSO stock solutions by using HPLC UV.

Intrinsic permeability measured across Caco2 membranes; efflux ratio ER = (PappBA)/(PappAB).

Human and mouse liver microsome intrinsic clearance (μL/min/mg prot).

Plasma protein binding (as fraction unbound %). *n.a.: no result available due to low recovery.

Human/mouse and lung tissue binding (as fraction unbound %). *n.a.: no result available due to low recovery.

To improve the profile for inhaled administration, we applied an “inhalation-by-design”30 strategy, which exploits specific criteria to minimize systemic exposure and to favor drug efficacy in the lung. Moreover, the introduction of a basic center could have a beneficial effect in modulating solubility and membrane permeability to achieve a prolonged lung retention.31 So, the free amino group decorating the pyridine ring of 4 was used as a chemical handle to introduce basic groups. Given the favorable orientation of this group on the pyridine hinge binder, located near the rim of the ATP-binding cavity, we postulated that elongated and protonated aminoalkyl chains branching from this position should not change ligand binding. A small set of amines covering a range of calculated pKa values from 7.0 to 9.5 was selected to explore the effect of compound basicity on the overall ADME profile of the resulting compounds (19–24, Table 4). Compound 19, with an alkyl chain bearing a N-methyl piperazine, showed cell-free and cell-based potencies comparable to those of 4 (pKi = 8.55, pIC50 = 5.66). Interestingly, the same basic group introduced through an amide bond as in 20 led to a boost in potency both in the biochemical (pKi = 9.29) and in the cell-based (pIC50 = 6.82) assays. In terms of the in vitro ADME properties, both 19 and 20 showed an increase in solubility and a decrease in permeability. These encouraging results prompted us to continue the exploration of other basic groups, retaining the amide group as the most suitable anchor point. The introduction of morpholine as a weak basic group led to 21, which showed an overall profile similar to compound 20. Besides, higher pKa basic centers such as N-methyl-piperidine, N,N-dimethyl amine, and monomethyl amine were also installed (22–24, Table 4). These compounds maintained a single-digit nanomolar potency in the biochemical assay and showed significant (from 100- to 1000-fold) drops in potency in the cellular context, with compound 23 displaying the best cell-based potency (pIC50 = 7.19) while maintaining the desired solubility and permeability. Compounds 19–24 were also tested for liver microsomal clearance to preliminarily evaluate their systemic exposure and characterized for their plasma and lung protein binding.

All compounds tested were rapidly cleared in mouse tissue, while high clearance in human microsomes was observed only for derivatives 19–21 and 24. All analogues exhibited a low free fraction in human and mouse plasma (from 8% to 14%) as well as in mouse lung (from 1 to 3.5).

Compound 23, characterized by the best cellular potency, was profiled in a kinase selectivity assay (HotSpot, Reaction Biology) against a selected panel of 57 kinases at 1 μM concentration, inhibiting 13 kinases besides ALK5 (inhibition > 50%, 1 μM concentration, see the Supporting Information), which represents an acceptable selectivity profile for an advanced hit compound.

At the end of this chemical exploration, compounds 20 and 23 stood out as the most interesting hits in terms of the in vitro pharmacological profile. Indeed, while 20 showed very low permeability and high microsomal clearance, 23 was characterized by good cellular potency and balanced lung tissue binding. Taken together, these observations strongly confirmed that a pyridazine–amino–pyridine scaffold functionalized with a basic chain represented a valid structural moiety for the development of ALK5 modulators potentially suited for an inhaled administration.

The N-linked pyridazyl compounds 2A, 4–9, and 19–24 were prepared as outlined in Scheme 1. Briefly, a 4-chloro or 4-amino 6-chloropyrazine scaffold (25a and 25b) was reacted in a Suzuki coupling with the (5-chloro-2-fluorophenyl) boronic acid, affording derivatives 26a and 26b. Buchwald–Hartwig amination with suitably decorated 4-halopyridines or 4-aminopyridines gave 2A, 8–9, and 20–23 and intermediates 27a–27d, 45, and 49. Acid-mediated Boc deprotection of compounds 27a, 45, and 49 yielded compounds 4, 19, and 24, respectively. The reduction of the nitro group in 27b furnished 5. Lastly, heating in the presence of ammonia transformed the ester derivatives 27c and 27d into the corresponding amides 6 and 7.

Scheme 1. Series A: N-Linked Pyridazyl Compounds 2A, 4–9, and 19–24.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(AcO)2, Cs2CO3, 1,4 dioxane/water, 75 °C, 67% or KF, PdCl2(PPh3)2 MeCN/water, 95 °C, 52%. (b) Pd2(dba)3, Xantphos K3PO4, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C or Pd(OAc)2 70% or Xantphos, NaOtBu, 1,4-dioxane, 130 °C microwave irradiation, 10%. (c) Pd(OAc)2, Xantphos, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, 100–110 °C, heating or microwave irradiation 45–54% Pd2(dba)3, DTBPF, NaOtBu, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C, 14%; Pd(OAc), Xantphos, NaOtBu, 1,4-dioxane, 130 °C MW, 10%; Pd2(dba)3, Xantphos K3PO4, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C, 73%. (d) TFA, DCM, rt, 54%. (e) NH4Cl, ethanol/water, reflux, 49%. (f) NH3, MeOH, 60 °C, 21–30%.

In conclusion, we have identified substituted aminopyridazines as novel potent inhibitors of the ALK5 receptor by following a rational design approach. The optimization of the initial pyridazine-based hit 4 was focused on the introduction of suitable exit vectors for further functionalization, which was required to pursue an “inhalation-by-design” strategy. Pleasingly, the derivatization of compound 4 with basic chains led to the advanced hits 20 and 23, which exhibited high cell-free potency, acceptable cell-based potency, adequate physicochemical properties, and an acceptable in vitro DMPK profile. These compounds served as starting points for a subsequent medicinal chemistry campaign devoted to the improvement of the overall in vitro profile, aiming at the identification of ALK5 inhibitors suitable for inhaled administration in in vivo animal models of lung fibrosis. This medicinal chemistry optimization will be described in future publications.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ALK5

activin receptor-like kinase

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00374.

Full experimental details for key compounds, biological protocols, and docking details (PDF)

Author Contributions

∇ These authors contributed equally. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that no major criticalities were identified for the reactions reported in this paper, based on our chemical risk assessment. However, we suggest performing a chemical risk assessment before reproducing any of them.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Massague J. How cells read TGF-β signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 169–178. 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R.; Zhang Y. E. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst R. J.; Hata A. Targeting the TGF-β signalling pathway in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discovery 2012, 11 (10), 790–811. 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. Y.; Qin L.; Simons M. TGF-β signaling pathways in human health and disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1–23. 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1113061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingling J. M.; Blanchard K. L.; Sawyer J. S. Development of TGF-β signaling inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discovery 2004, 3, 1011–1022. 10.1038/nrd1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed V. TGF-β Signaling in Cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 117, 1279–1287. 10.1002/jcb.25496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D. Transforming Growth Factor β. A Central Modulator of Pulmonary and Airway Inflammation and Fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006, 3, 413–417. 10.1513/pats.200601-008AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.-G.; Malek E.; Choi S. H.; Ignatz-Hoover J. J.; Driscoll J. J. Novel therapies emerging in oncology to target the TGF-β pathway. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 55. 10.1186/s13045-021-01053-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak S.; ten Dijke P. Targeting TGF-β Signaling in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 56–71. 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gramont A.; Faivre S.; Raymond E. Novel TGF-β inhibitors ready for prime time in onco-immunology. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1257453. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1257453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafoux D.; Lee W.-C. Strategies for TGF-β modulation: a review of recent patents. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2009, 19 (12), 1759–1769. 10.1517/13543770903397400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungefroren H. Blockade of TGF-signaling: A potential target for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 679–693. 10.1080/14728222.2019.1636034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielpour D. Advances and Challenges in Targeting TGF-β isoforms for Therapeutic Interventionof Cancer: A Mechanism-Based Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17 (4), 533. 10.3390/ph17040533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingling J. M.; McMillen W. T.; Yan L.; Huang H.; Sawyer J. S.; Graff J.; Clawson D. K.; Britt K. S.; Anderson B. D.; Beight D. W.; Desaiah D.; Lahn M. M.; Benhadji K. A.; Lallena M. J.; Holmgaard R. B.; Xu X.; Zhang F.; Manro J. R.; Iversen P. W.; Iyer C. V.; Brekken R. A.; Kalos M. D.; Driscoll K. E. Preclinical assessment of galunisertib (LY2157299 monohydrate), a first-in-class transforming growth factor-β receptor type I inhibitor. Oncotarget 2018, 9 (6), 6659–6677. 10.18632/oncotarget.23795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. H.; Krishnaiah M.; Sreenu D.; Subrahmanyam V. B.; Rao K. S.; Lee H. J.; Park S.-J.; Park H.-J.; Lee K.; Sheen Y.-Y.; Kim D.-K. Discovery of N-((4-([1,2,4]Triazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-6-yl)-5-(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methyl)-2-fluoroaniline (EW-7197): A Highly Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable Inhibitor of TGF-β Type I Receptor Kinase as Cancer Immunotherapeutic/Antifibrotic Agent. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4213–4238. 10.1021/jm500115w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle P.; Li M.; Douglass J.; Stewart A. Safer approaches to therapeutic modulation of TGF-β signaling for respiratory disease. Pharmacology&Therapeutics 2018, 187, 98–113. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge R.; Huang G. M. Targeting transforming growth factor beta signaling in metastatic osteosarcoma. J. Bone Oncol. 2023, 43, 100513. 10.1016/j.jbo.2023.100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbertz S.; Sawyer J. S.; Stauber A. J.; Gueorguieva I.; Driscoll K. E.; Estrem S. T.; Cleverly A. L.; Desaiah D.; Guba S. C.; Benhadji K. A.; Slapak C. A.; Lahn M. M. Clinical development of galunisertib (LY2157299 monohydrate), a small molecule inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 4479–4499. 10.2147/DDDT.S86621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap T. A.; Vieito M.; Baldini C.; Sepúlveda-Sánchez J. M.; Kondo S.; Simonelli M.; Melisi D. First-in-human phase I study of a next-generation, oral, TGF-β receptor 1 inhibitor, LY3200882, in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27 (24), 6666–6676. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TD-1058 First-In-Human Study in Healthy Subjects and Subjects with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. NCT04589260, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04589260.

- Phase I Study to Assess Safety, Tolerability, PK and PD of AGMB-447 in Healthy Participants and Participants With IPF. NCT06181370, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06181370.

- Maher J. M.; Zhang R.; Palanisamy G.; Perkins K.; Liu L.; Brassil P.; McNamara A.; Lo A.; Hughes A. D.; Kanodia J.; Kulyk S.; Nikula K. J.; Dengler H. S.; Scandurra A.; Lua I.; Harstad E. Lung-restricted ALK5 inhibition avoids systemic toxicities associated with TGF-β pathway inhibition. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 438, 115905. 10.1016/j.taap.2022.115905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. H.; Hughes A. D. Inhalation by design. Future Medicinal Chemistry 2011, 3 (13), 1563–1565. 10.4155/fmc.11.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour M. A.; Hassan G. S.; Serya R. A.; Jaballah M. Y.; Abouzid K. A. Advances in the discovery of activin receptor-like kinase 5 (ALK5) inhibitors. Bioorganic Chemistry 2024, 147, 107332. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhao Y.; Tebben A. J.; Sheriff S.; Ruzanov M.; Fereshteh M. P.; Fan Y.; Lippy J.; Swanson J.; Ho C.-P.; Wautlet B. S.; Rose A.; Parrish K.; Yang Z.; Donnell A. F.; Zhang L.; Fink B. E.; Vite G. D.; Augustine-Rauch K.; Fargnoli J.; Borzilleri R. M. Discovery of 4-azaindole inhibitors of TGF-βRI as immuno-oncology agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9 (11), 1117–1122. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella T.; Gelman M.; Hong H.; Darwish I. S.; Singh R.; Yu J.; Borzilleri R. M.; Velaparthi U.; Liu P.; Darne C.; Rahaman H.; Warrier J. S.. Preparation of imidazole and thiazole compounds as TGF-β inhibitors. WO2016/140884.; Dorsch D.; Jonczyk A.; Hoelzemann G.; Amendt C.; Zenke F.. Preparation of pyridopyrazine derivatives for use as TGFβ receptor kinases inhibitors. WO2012/119690.; Jonczyk A.; Dorsch D.; Zenke F.; Amendt C.. Naphthyridine derivatives as TGFβ receptor kinase inhibitors and their preparation and use for the treatment of diseases. WO2011/101069.; Jonczyk A.; Dorsch D.; Hoelzemann G.; Amendt C.; Zenke F.. Preparation of hetaryl-[1,8]naphthyridine derivatives as therapeutic inhibitors of ATP-consuming proteins, such as TGFβ receptor kinase. WO2011/095196.; Kulyk S.; Ownes C.; Sullivan S. D. E.; Kozak J.; Hughes A. D.. Preparation of disubstituted 1,5-naphthyridines as ALK5 inhibitors and therapeutic uses thereof. WO2020/123453.

- Leblanc C.; Pulz R. A.; Stiefl N. J.. Preparation of pyrrolopyrimidines and pyrrolopyridines for treating ALK-5 and ALK-4 receptor-mediated diseases. US20090181941.; Leblanc C.; Pipet M. N. P.; Fairhurst R. A.; Adcock C.; Pulz R. A.; Shaw D.; Stiefl N. J.. Preparation of pyrimidine derivatives as ALK-5 inhibitors. WO2008006583.

- Gellibert F.; de Gouville A.-C.; Woolven J.; Mathews N.; Nguyen V.-L.; Bertho-Ruault C.; Patikis A.; Grygielko E. T.; Laping N. J.; Huet S. Discovery of 4-{4-[3-(Pyridin-2-yl)-1 H-pyrazol-4-yl] pyridin-2-yl}-N-(tetrahydro-2 H-pyran-4-yl) benzamide (GW788388): a potent, selective, and orally active transforming growth factor-β type I receptor inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 2210. 10.1021/jm0509905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gellibert F.; Fouchet M.-H.; Nguyen V.-L.; Wang R.; Krysa G.; de Gouville A.-C.; Huet S.; Dodic N. Design of novel quinazoline derivatives and related analogues as potent and selective ALK5 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2277. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung-Chi C.; Prusoff W. H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochemical pharmacology. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunhita R.; Prabha K. S.; Prasanna P. M. Drug Delivery and its Development for Pulmonary System. Int. J. Pharm. Chem. and Bio. Sc. 2011, 1 (1), 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz L.; Bailey A.; Cadogan E.; Connolly S.; Jewell R.; Jordan S.; Kindon N.; Lister A.; Lawson M.; Mullen A.; Dainty I.; Nicholls D.; Paine S.; Pairaudeau G.; Stocks M. J.; Thorne P.; Young A. From libraries to candidate: the discovery of new ultra long-acting dibasic β2-adrenoceptor agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 689–695. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.