Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorders (SUDs) frequently co-occur, and individuals with co-occurring PTSD and SUD often experience more complex treatment challenges and poorer outcomes compared to those with either condition alone. Integrative treatment approaches that simultaneously address both PTSD and SUD are considered the most effective and include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies. In recent years, complementary interventions have garnered increased attention due to their broad appeal and potential therapeutic benefits in enhancing existing treatments for PTSD and SUD. This review explores the existing literature on the use of nature-based activities, such as hiking, camping, sailing, and surfing in treating individuals with co-occurring PTSD and SUD. Nature-based activities offer promising adjunctive benefits, including the reduction of PTSD symptoms and craving levels. While evidence supports the therapeutic value of nature-based activities, current research remains limited. Further research is needed to better understand their therapeutic role and to refine their implementation in clinical practice.

Keywords: nature, PTSD, substance use disorder, addiction, complementary and integrative health

Background

PTSD and SUDs frequently co-occur. Patients with PTSD are reported to be up to 14 times more likely to develop SUD and nearly half (46.4%) of individuals with PTSD also meet the criteria for a SUD.1-3 PTSD and SUDs are chronic conditions associated with significant distress and functional impairment. Individuals with co-occurring PTSD and SUD exhibit poorer social functioning, higher rates of suicide attempts, increased violence, and legal problems, as well as a less favorable treatment prognosis than those with either disorder alone.4-9

The interaction between PTSD and SUDs involves multifaceted mechanisms.10-12 The historical treatment model, which prioritizes treating SUD first and deferring PTSD management until after abstinence, undermines the significant interplay between these 2 disorders. Integrative approaches involving psychosocial and pharmacological methods have emerged as the preferred treatment model.13,14 Trauma-focused therapies are recommended due to their established efficacy in reducing PTSD symptoms but are associated with higher dropout rates compared to non-trauma-focused approaches. 15 Exploring additional interventions to enhance current treatments and sustain patient engagement during and after treatment is crucial. Complementary practices, defined as non-traditional approaches used alongside conventional Western medical practices, have gained increasing attention as part of a holistic approach to recovery.16,17 Given that physical exercise18,19 and exposure to natural environments are potential complementary treatment approaches for PTSD and SUDs,20-23 we conducted a PubMed search using the terms “hiking,” “biking,” “walking,” “running,” “jogging,” “surfing,” “sailing,” “kayaking,” “climbing,” “nature,” “forest,” “adventure,” “outdoor,” “PTSD,” and “SUD” to review the literature on nature-based activities. We examined nature-based activities as a potentially promising approach. In this paper, we review interventional research on nature-based activities, discuss research gaps and limitations in existing studies, and suggest future directions.

Rationale and Potential Mechanisms of Nature-Based Activities

Interactions with Nature/Green Spaces

Exposure to green spaces is generally associated with improved psychological well-being. 24 For example, exposure to green spaces during childhood has been linked to a reduced risk of psychiatric disorders, as shown in a nationwide study from Denmark. 23 The presence of green space within a 210 × 210 m area surrounding each person’s residence before age 10 was determined from high-resolution satellite data. Results demonstrated that children raised in areas with the least green space had up to a 55% higher risk of developing a psychiatric disorder compared to those who lived with the highest level of green space after adjusting for various individual and socioeconomic confounding factors. 23

Additionally, exposure to green spaces has been shown to enhance SUD outcomes. For instance, access to gardens and residential views with more than 25% greenspace has been associated with reduced cravings for various substances compared to those with no access to such resources. 25 Other studies have found that neighborhoods with higher percentages of green space (categorized into quartiles for comparison) have higher smoking cessation rates and lower smoking prevalence than those with less green space. 26 Moreover, greater residential greenness has been associated with lower odds of tobacco use and frequent binge drinking, although it has also been linked to higher odds of marijuana use. 21 Exposure to natural scenes through photos, 3D images, virtual reality, and videos of natural landscapes has also been shown to lead to psychological benefits and more relaxed physiological responses than viewing matched controls. 27 In another study, participants who viewed natural scenery before a delay discounting task were observed to be less impulsive than those who viewed built environments. In other words, the latter group tended to prefer immediate, smaller rewards over larger, delayed rewards, placing less value on the future, a behavioral trait linked to addiction. 28 Similarly, in another study, women with SUD residing at a treatment facility began their days by either watching a nature video or engaging in mindfulness-based activities. The study concluded that viewing natural scenery was as beneficial as mindfulness practices, with both interventions leading to significant decreases in heart rate and negative affect, as well as improved overall mood. 29

The benefits of exposure to nature may be driven by an evolutionarily based preference for connection to nature. 30 Mediational analysis from Mayer et al.’s study, which examined the effects of exposure to nature on positive affect and cognitive ability, indicated that the positive effects of nature exposure are partially mediated by increases in connectedness to nature. 31 Similarly, in a study of individuals and communities affected by bushfires, stronger attachment to the natural environment was associated with higher resilience, posttraumatic growth, and reduced psychological distress and fire-related PTSD symptoms. 32 Similarly, in a qualitative study of combat veterans, Westlund et al highlighted the importance of interconnection with nature in recovery. Quotes from veterans included: “There’s something about the outdoors that’s helped me move on from my service and look inside. And to become—I wouldn’t say whole again, but just not so military, if you will.” (Westlund, 2015, p. 165) Another veteran remarked, “You’re more aware of the things around you than having to respond to every circumstance. Day turns to night, and you stop. Light comes in the morning, you get up. There’s a rhythm that’s much different than somebody yelling at you to do this or that. Or you’ve got to punch a clock at a certain time.” (Westlund, 2015, p 166) 33

Nature and Mindfulness

One of the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of nature-based activities on psychological well-being may be mindfulness.34,35 Mindfulness can be defined as increased awareness of one’s surroundings, emotions, thoughts, and bodily sensations in the present moment without judgment. 36 Natural environments may enhance mindfulness by increasing sensory engagement and promoting calm, while mindfulness may amplify nature’s restorative effects through heightened awareness and a deeper connection to the natural surroundings. 37

The potential synergy between mindfulness and exposure to nature has led to the development of unique nature-based mindfulness interventions.38,39 Shinrin-yoku, a Japanese practice of “forest bathing,” involves engaging the 5 senses by focusing on different elements, such as the range of leaf colors and the sounds of streams. Shinrin-yoku has been shown to reduce depression, stress, and anxiety, and previous research suggests it may be a potential treatment for addiction that warrants further exploration. 40 Similarly, a mindfulness-based sailing intervention for veterans with psychiatric disorders (SUD 76% and PTSD 72%) was found to be both enjoyable and effective, enhancing psychobiological flexibility and state mindfulness. 41 Brain imaging findings with exposure to nature also parallel the effects of mindfulness practice. For instance, amygdala activation in response to fearful faces and a social stress task was reduced after walking in nature compared to an urban setting. 42 This finding is very similar to the effects of mindfulness on amygdala activation.43-45 However, these 2 interventions have not been directly compared, and whether a combined approach would have synergistic effects warrants further investigation.

Outdoor Exercise

Physical activity has been proposed as an effective intervention to improve PTSD outcomes.18,46,47 Potential mechanisms by which aerobic exercise positively impacts PTSD symptoms include improved cognitive function and modulation of neuronal, endocrinological, and immunological systems. Another potential mechanism is the reduction of sensitivity to internal physiological arousal cues, such as increased heart rate, through repeated exposure and the association of these bodily sensations with non-trauma-related situations.48,49 Exercise-induced bodily sensations that resemble unpleasant PTSD-related symptoms may contribute to non-adherence, highlighting the importance of incorporating psychotherapeutic strategies to address such challenges. Similarly, biopsychosocial mechanisms have been suggested for the role of exercise in the treatment of SUDs. The formation of exercise habits has been proposed as a replacement for habitual substance use by engaging the dopaminergic neural pathway of “craving-driving-behavior-reward” and facilitating the recovery of the dopamine system after chronic drug use47,50 Regular aerobic exercise training may also induce neuroadaptation within the central opioid receptor system 51 and increase endocannabinoids,52,53 warranting further research to assess its effectiveness in treating opioid and cannabis use disorders. Taken together, one could hypothesize that exercise may be beneficial for co-occurring PTSD and SUDs. For instance, exercise could serve as a replacement for self-medicating with substances to alleviate PTSD-related symptoms, as supported by prior research demonstrating the effectiveness of physical exercise in reducing anxiety and depression in individuals with SUD. 54

Outdoor exercise may harness the benefits of both exposure to nature and physical activity. 55 In a systematic review of longitudinal trials comparing indoor and outdoor exercise, all statistically significant differences in outcomes favored outdoor exercises, with enhanced positive emotions, tranquility, and psychological restoration.55-58

Community Building and Engagement

Community engagement has been recognized as an effective and essential component of substance use prevention and treatment by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 59 In substance use recovery, the formation of “recovery communities” and the establishment of social bonds through substance-free activities help reduce social isolation and sustain sobriety. 60 Similarly, social isolation is commonly experienced in patients with PTSD, and social support, along with a sense of belonging, has been associated with improved resilience and reduced PTSD symptoms in prior research.61,62 An 8-year longitudinal study demonstrated that perceived social support has protective effects against the development of PTSD symptoms following physical assault. 63

Public gardens or gardening programs may offer a practical means of fostering community building to enhance psychological well-being.64,65 Observational and interventional studies suggest that gardening and horticultural therapy positively affect well-being and quality of life, including among vulnerable populations. 66 As part of the “Green Social Prescribing” initiative by the NHS in the UK, health care professionals prescribe nature-based activities, such as community gardening, to individuals who may benefit from them.67,68 The Veterans Affairs Farming and Recovery Mental Health Services (VA FARMS) initiative is a similar program in the US, offering agricultural training to veterans, particularly those with PTSD. This program has been implemented at 10 sites, with each location tailoring its approach to local needs. 69

New Hobbies and Substance-Free Reinforcements

Forming new habits and routines is an essential aspect of care during recovery. Because individuals recovering from SUDs are no longer occupied with substance-related activities (obtaining, using, recovering), managing unused time can become a significant challenge. 70 Therefore, substance use programs should incorporate greater access to and increased time spent in enjoyable and rewarding experiences to sustain abstinence. 71 Engaging in such activities reinforces abstinent behaviors, while the absence of these positive reinforcers can undermine recovery.72-74 Individuals with SUD have reported that engagement in substance-free activities is a critical component of successful recovery. 75

In PTSD, avoidance symptoms often interfere with previously satisfying activities. Enhancing daily routines may promote psychological resilience during and after potentially traumatic events. 76 We suggest that exposure to nature is an ideal candidate activity to increase engagement and positive affect. As one veteran shared in Westlund’s study about his experience in nature, “[: It] allowed us [veterans] to create some space outside that essentially is a safe space for us to just talk about [experiences of post-combat stress reactions]. I’ve spent a lot of time with veterans in other situations, but not being outdoors, the same types of conversations don’t happen.” (Westlund, 2015, p. 167) 33

Nature-Based Intervention Research in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Substance Use Disorders

SUDs

A study demonstrated that after a one-hour walk in nature, patients with SUD showed significantly reduced craving levels compared to pre-walk values and craving levels after a city walk. 77 In this study, 24 patients with SUD who were receiving care at a residential center were divided into 3 groups of nature walk (N = 8), urban walk (N = 8), and staying at the residential center (N = 8). Enhanced recovery outcomes in SUD patients participating in these activities may also be attributed to gaining a sense of accomplishment and belonging. These themes were identified in reports from 61 participants who completed a supervised exercise program (boot camp workouts, walking/running practice, and a race event) while receiving SUD treatment at a recovery facility. 78 In a study of a camping intervention, 13 patients in substance use treatment participated in a 3-day residential program that integrated outdoor adventure therapy, therapeutic camping, and relapse prevention. The control group consisted of 18 participants who received the usual relapse prevention program. Significant reductions were observed in autonomic arousal, frequency of negative thoughts, and alcohol cravings with the integrated approach. Ten months after the 3-day intervention, the relapse rate was 31% in the intervention group and 58% in the comparison group. 79 A retrospective study utilized data collected for clinical purposes to assess a sailing adventure therapy (SAT) experience for veterans. Veterans who had received SUD treatment without SAT at the same residential program were selected as controls (N = 22) and matched with the intervention group (N = 22). Results showed no increases in short-term anxiety and negative affect, increased psychological flexibility, and a higher rate of residential treatment completion in the intervention group compared to the control. 80

PTSD

In a study comparing nature and urban hiking, 26 veterans with PTSD were randomized to 12-week interventions of 6 nature hikes (N = 13) or 6 urban hikes (N = 13). Participants who walked in a natural setting showed a greater reduction in self-reported PTSD symptom scores (PTSD Checklist-5) at 12 and 24 weeks compared to the urban hiking group. 81 Achabaeva et al conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial where the control group (N = 38) received physical training, individual psychotherapy, and pharmacological treatments, while the intervention group (N = 36) additionally received walking in the mid-mountain Natural Park and nitrogen-thermal baths. 82 They found that the addition of mountain walks and thermal baths to standard PTSD treatment enhanced psycho-emotional status. However, this additive design does not control for the effects of additional activity and contact. 82 Another study on patients with severe anxiety/PTSD randomly assigned participants to climbing exercise (N = 27), Nordic walking (N = 23), or a control condition of social contact (N = 23) for 8 90-minute sessions. The results showed no additional therapeutic effects of exercise (climbing and Nordic walking) on psychological outcomes. 83 In a trauma-focused therapy program for veterans with PTSD (N = 49), optional outdoor activities such as hiking, cycling, and climbing were offered. The study found that greater time outdoors correlated with decreased PTSD symptoms within individuals but not between individuals, suggesting that the therapeutic effects of time outdoors may be person-specific. The more time an individual spends outdoors on any given day, the greater the reduction in PTSD symptoms for that individual the following day. 84 One limitation of this study is that participants chose their outdoor activities based on personal preference, which hinders clear comparisons of effects between individuals. A pilot trial study assessed the feasibility and acceptability of outdoor walking during trauma-focused psychotherapy sessions. The intervention was highly acceptable among both patients (N = 20) and therapists (N = 5), with patients demonstrating a clinically significant reduction in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) scores after 12 weeks. 85 Future studies comparing seated and walking therapy can clarify whether any psychotherapeutic benefits can be attributed to walking.

Similarly, nature-based activities in “blue” spaces (i.e., water) have shown promising results.41,86,87 Surfing as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD was assessed in an uncontrolled pretest-posttest study, with preliminary results suggesting therapeutic effects on PTSD symptoms. 88 In this feasibility study, 14 veterans were enrolled, 11 completed the study, and 10 attended more than 3 of the total 5 sessions. Another study of integrated mindfulness and sailing programs demonstrated increased psychological flexibility and mindfulness compared to the control group, which did not receive this intervention. The control group received the usual treatment and services at the same medical center and was selected retrospectively from medical records (N = 25), matched to the intervention group (N = 25) by gender, age, and diagnosis. Participants had either SUD or at least one psychiatric disorder, with the most common being SUD (76%) and PTSD (72%). 41 These findings align with results from other sailing studies showing significant improvements in symptomatology, 86 perceived control over illness and daily functioning in patients with PTSD. 87

A 3-day river rafting, hiking, and camping trip for a group of 13 veterans with PTSD was found to be positively impactful. This study did not include structured or formal therapy sessions as part of the intervention. Each day began with rising at sunrise and dismantling the camp and ended with setting up camp and gathering around an evening campfire, with river floats and day hikes in between. Participants were instructed to keep a journal and record their thoughts throughout the trip, which were collected upon completion. Paddling and kayaking appeared to alleviate avoidance and numbness symptoms, as highlighted by veterans’ reports of regaining the capacity to experience joy. Several participants reported needing fewer medications during the trip. One veteran shared, “At home, I usually take anxiety pills and sleeping pills at night. Out here, I haven’t had to take either one. The music around the campfire was enough to lull me right to sleep. We are so active during the day, rafting and hiking, that I have no trouble going to sleep at night. That makes me very happy.” 89 Early in the trip, some veterans experienced re-experiencing symptoms triggered by the terrain, reminding them of a war zone. One veteran noted continually scanning the horizon for the enemy. However, as they acclimatized to the river experience, these symptoms appeared to dissipate, with nearly all participants reporting a sense of peace and relaxation. These reports demonstrate the possibility of habituation with sustained exposure in a supportive environment.

An additional study offered combined mindfulness activities, nature-based tasks (including planting trees, splitting wood, and performing routine tasks with a gardener), and individual therapeutic sessions (either seated in a sheltered area or during walks in the garden) in a forest therapy garden. The program consisted of 3 hours of therapy, 3 times per week, over 10 weeks for 8 veterans with PTSD symptoms. Participants experienced the natural environments as comfortable, and a shift in preference from locations offering refuge to more open areas was observed throughout the study. For most veterans, nature remained an important part of their lives in different ways after 1 year. One veteran shared: “I found someone to do those things in nature with. We are 4-5 veterans and stay in nature for 2-3 days. The breathing … to breathe and feel the ground under my feet. I become more conscious of it when I am in nature.” 90 Similarly, another study found that veterans with PTSD (N = 19) highly positively received other immersive experiences in nature, such as birdwatching, assisting with wildlife rehabilitation, and observing wildlife sanctuaries. 91

The results of other studies that explored wildlife immersion, 91 gardening,90,92 fishing, 93 angling, equine care, archery, falconry, 94 cycling, kayaking, pickleball, 95 and camping 89 for PTSD recovery are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intervention Research of Nature-based Activities in Treatment of PTSD and SUDs.

| Article | Participants | Intervention | Results/Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substance use disorder (SUD) studies | |||

| Benvegnù G et al, 2024 | 24 SUD patients divided into 3 groups of 8 (nature walk, urban walk, and staying at the residential center) | Nature walks vs urban walks vs staying at the residential center | Craving decreased significantly from pre- to post- nature walk, and lower post-nature than post-urban walk |

| Dai CL et al, 2020 | 109 patients residing in a treatment facility for SUD were recruited. 61 completed the intervention | Walking/Running program + racing | Positive impact on recovery, sense of achievement, and belonging |

| Marchand WR et al, 2022 | 25 veterans with psychiatric disorders (SUD 76%, PTSD 72%) 25 in the matched control group (retrospectively obtained from medical records) | Mindfulness-based therapeutic sailing | Increased psychological flexibility and mindfulness. The intervention was perceived as pleasurable by the participants |

| Bennett LW | 31 patients with SUD (camping = 13, usual care = 18) | Therapeutic camping program vs usual care | Significant improvements in autonomic arousal, frequency of negative thoughts, and alcohol craving in the camping group |

| Marchand WR et al, 2018 | 44 veterans with SUD (sailing = 22, control = 22) | Sailing adventure therapy | Significant increase in psychological flexibility Greater likelihood of completing residential SUD treatment. No effect on rate of psychiatric and SUD readmissions in the 12 months after discharge |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) studies | |||

| Littman AJ et al, 2021 | 26 veterans with PTSD (nature hike = 13, urban hike = 13) | Nature vs urban hiking | Acceptability of both nature and urban hiking was high. In the nature hiking group, median PTSD symptom scores (PTSD Checklist-5) improved more at 12 and 24 weeks compared to the urban hiking group |

| Achabaeva AB et al, 2023 | 74 PTSD patients (main group = 36, and control group = 38) | Tx as usual vs tx as usual +controlled walking in the mid-mountain natural park and nitrogen-thermal baths | Significant improvement in psycho-emotional status with the added natural therapy |

| Bichler CS et al, 2022 | 73 patients with anxiety/PTSD (climbing = 27, Nordic walking = 23, social contact = 23) | Climbing exercise vs Nordic walking (outdoor if weather allowed) vs social contact (movie watching and discussion group) | Anxiety decreased in all groups |

| Bettmann JE et al, 2021 | 49 veterans with PTSD | Hiking, cycling, and rock climbing | The more time spent outdoors, the greater the reduction in PTSD symptoms |

| Koziel N et al, 2022 | 20 female patients in an outpatient trauma therapy program | Walking during psychotherapy sessions | Feasible and acceptable to incorporate outdoor walking during trauma therapy sessions for patients and therapists. Significant decrease in PTSD symptoms (PCL-5) at 12 weeks |

| Detweiler MB et al, 2015 | 49 veterans randomly assigned to 2 groups | Horticultural therapy vs non-horticultural occupational therapy | Trends suggested that horticultural therapy may modulate stress. No statistically significant difference observed |

| Rogers CM et al, 2014 | 14 veterans with PTSD symptoms | Ocean therapy (surfing) | Clinically meaningful improvements in PTSD and depressive symptoms |

| Perry DJ et al, 2024 | 19 veterans with PTSD symptoms | Nature and wildlife immersion experiences | Nature and wildlife immersion intervention was acceptable and feasible and perceived as greatly enjoyable by participants |

| Poulsen DV et al, 2016 | 8 veterans with PTSD symptoms | Mindfulness activities + nature-based activities + individual therapy sessions in a forest therapy garden | Participants gained tools to manage stress and showed improvement in PTSD symptoms |

| Gelkopf M et al, 2013 | 42 veterans with PTSD (sailing = 22, control = 20) | Nature adventure rehabilitation (sailing) | Significant improvements in PTSD symptoms, depression, social and emotional quality of life, daily functioning, hope and perceived control over illness in the sailing group |

| Vella JE et al, 2013 | 74 veterans with PTSD | Outdoor recreation intervention (fly-fishing) | Significant improvement in sleep quality and reductions in perceptual stress and PTSD symptoms from baseline to follow-up periods |

| Walter KH et al, 2023 | 74 veterans (PTSD = 20, no PTSD = 54) | Recreational activity (cycling, surfing, sailing, kayaking, and archery/pickleball) | Those with PTSD experienced significant improvements in PTSD symptoms from pre- to post-program, effect was lost at 3-month follow-up |

| Zabag R et al, 2020 | 39 patients with PTSD diagnosis (sailing = 17, no sailing = 22) 38 healthy controls (sailing = 18 who no sailing = 20) |

Sailing vs no-sailing and a performance-based reversal learning paradigm to assess cognitive flexibility | Significantly lower PTSD and trait anxiety symptoms in the PTSD-sailing group (vs PTSD-no-sailing group) selective impairment in reversing the outcome of a negative stimulus in PTSD- no-sailing group selective impairment in reversing the outcome of a positive stimulus in PTSD-sailing group |

| Dustin D et al, 2011 | 13 veterans coping with PTSD | 3-day river rafting/hiking/camping + journaling | Qualitative data suggested that therapeutic recreation service is well-suited to contribute to the rehabilitation of veterans coping with PTSD |

| Wheeler M et al, 2020 | Experiment 1: 30 veterans with PTSD Experiment 2: 13 veterans with PTSD in the angling intervention group, and 12 in the waitlist control group | Pretest-posttest within participant Experiment 1: group outdoor activity (angling, equine care, or archery and falconry combined). Waitlist controlled randomized. Experiment 2: angling vs waitlist | Experiment 1: significant within participant reduction in PTSD symptoms, sustained over time. Experiment 2: significant reduction in PTSD symptoms in the intervention group relative to waitlist controls at 2-weeks post-intervention. |

Key Considerations for Recommending Nature-Based Activities

When recommending nature-based activities in clinical practice, we suggest a collaborative approach to determine the most beneficial activity for each patient. This collaboration should consider personal preferences, accessibility, symptomatology, potential trauma-related triggers, substance-related cues, physical ability, and treatment goals. For patients in earlier stages of PTSD treatment who experience significant avoidance and heightened sensitivity to social triggers, solo activities such as walking, hiking, and surfing in preferred natural environments during less crowded times may be the most suitable starting point. A gradual transition to more stimulating environments and group activities, such as climbing and group camping, can be introduced as they progress in their treatment. Depending on symptom severity, it may be beneficial for the therapist to assist the patient with initial attempts, such as engaging in walking therapy or holding sessions in a natural environment, if circumstances allow.

For those sensitive to physiological changes from exercise, such as increased heart rate, beginning with less strenuous activities like walking and gardening is essential, with gradual progression to more intense activities such as running and river rafting. For patients unable to engage in these activities due to physical limitations, more passive options like birdwatching and viewing natural scenes, even through videos and images, can still be beneficial. When selecting an activity and community, it is crucial to address potential substance-related cues and establish pre-coping strategies. It is also important to recognize that some group settings may involve substance use, and ensuring the chosen community provides a safe and supportive environment is key. Incorporating nature-based activities into residential SUD treatment programs can familiarize patients with potential challenges while helping them develop coping skills in a structured environment, ensuring a smoother transition post-discharge. Additionally, teaching patient’s mindfulness practices to use in nature may enhance the therapeutic effects of these activities.

Previous research suggests that psychological benefits can be gained across various types of nature-based activities. Studies suggest that even a one-hour walk in nature can have positive effects on stress-related brain regions. 42 For SUDs, a one-hour walk has been shown to help reduce cravings, 77 offering a simple and accessible starting point for patients with SUDs. One study focusing on the dose of nature exposure in PTSD found that the amount of time outdoors required to improve symptoms varies from person to person. 84 For instance, one individual might benefit from spending 2 hours outside daily, while another may achieve similar results with just half an hour. Furthermore, the study results showed that, within individuals, more time spent outdoors on a given day was associated with greater reductions in PTSD symptoms. 84

Thus, while prior research points to benefits of specific activities, more research is needed to form a consensus about the optimal duration, activity type, and frequency of nature engagement.

As future studies evaluate and compare the effects of different types, frequencies, and durations of nature-based activities, providers will be able to offer more evidence-based recommendations regarding the selection and frequency of these activities.

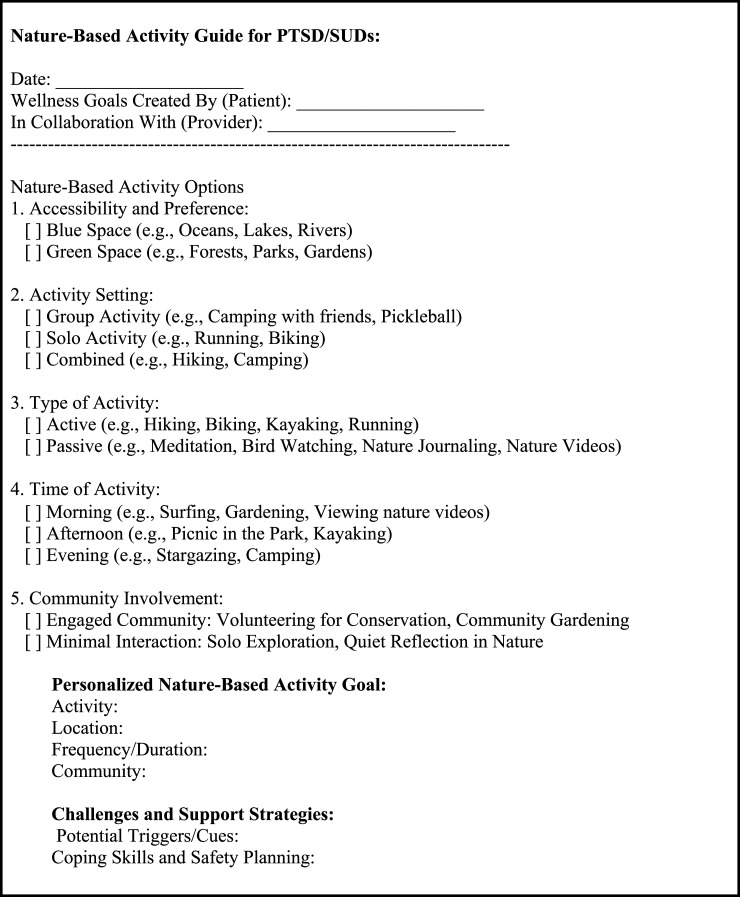

Figure 1 presents a suggested nature-based activity guide for patients with PTSD/SUDs. Providing guidance on nature-based activities, such as discussing the frequency and duration of the activities, may assist in setting realistic goals. Unlike medication prescriptions, which follow specific dosing for optimal efficacy and safety, a collaborative approach to this guidance allows for greater flexibility, offering a more personalized and holistic treatment strategy.

Figure 1.

A suggested nature-based activity guide with goal setting for patients with PTSD/SUDs.

Suggestions for Future Directions

Despite the potential therapeutic effects of nature-based interventions, there is a significant research gap in the implementation and evaluation of these interventions, particularly in SUDs. We recommend future clinical trials with larger sample sizes that include individuals with SUDs and co-occurring PTSD and SUDs to assess and compare the effects of these interventions with appropriate controls. These trials should consider factors such as mindfulness, exercise, community engagement, structure, and reinforcement. It will also be crucial to explore the optimal ways to integrate these programs with standard care, such as medication and psychotherapy. Preparation for nature-based activities through traditional care may help patients with PTSD/SUDs face the challenges of these programs, including exposure to trauma cues and substance-related triggers during participation. Alternatively, nature-based activities may promote readiness for change. Models that incorporate both individual and group-based activities appear to be promising, and future studies should investigate the most effective modalities. Finally, identifying the therapeutic mechanisms and potential risks of nature-based interventions for this population will help clinicians adopt a personalized approach and guide recommendations. The results of these studies may also inform policymakers and practitioners in developing new initiatives and improving existing programs67,69,96 to benefit patients with co-occurring PTSD and SUDs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Drs. Shirazi and Lang’s work on this manuscript was supported by the San Diego Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health (CESAMH). Dr Brody’s work was supported by grant funding from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (28IR-0064, ALB) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA053052). Dr Soltani does not have financial disclosures.

ORCID iD

Anaheed Shirazi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3516-7009

References

- 1.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from wave 2 of the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(3):456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford JD, Russo EM, Mallon SD. Integrating treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. J Counsel Dev. 2007;85(4):475. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chilcoat HD, Menard C. Epidemiological investigations: Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. In: Ouimette P, Brown PJ, eds. Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. American Psychological Association; 2003:9-28. doi: 10.1037/10460-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCauley JL, Killeen T, Gros DF, Brady KT, Back SE. Posttraumatic stress disorder and co-occurring substance use disorders: advances in assessment and treatment. Clin Psychol. 2012;19(3):12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouimette P, Goodwin E, Brown PJ. Health and well being of substance use disorder patients with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Addict Behav 2006;31(8):1415-23. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouimette PC, Brown PJ, Najavits LM. Course and treatment of patients with both substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addict Behav 1998;23(6):785-95. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00064-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kühner C, Will JP, Lortye SA, et al. The association between Post-Traumatic stress disorder and problematic alcohol and cannabis use in a multi-ethnic cohort in The Netherlands: The HELIUS study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024;21(10):1345. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21101345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett EL, Teesson M, Mills KL. Associations between substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder and the perpetration of violence: A longitudinal investigation. Addictive Behaviors 2014;39(6):1075-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norman SB, Haller M, Hamblen JL, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. The burden of co-occurring alcohol use disorder and PTSD in U.S. Military veterans: Comorbidities, functioning, and suicidality. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2018;32(2):224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13(5):206. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leeies M, Pagura J, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(8):731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somohano VC, Rehder KL, Dingle T, Shank T, Bowen S. PTSD symptom clusters and craving differs by primary drug of choice. J Dual Diagn. 2019;15(4):233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanagan JC, Korte KJ, Killeen TK, Back SE. Concurrent treatment of substance use and PTSD. Curr Psychiatr Rep. 2016;18(8):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen JP, Crawford EF, Kudler H. Nature and treatment of comorbid alcohol problems and post traumatic stress disorder among American military personnel and veterans. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis C, Roberts NP, Gibson S, Bisson JI. Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1709709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niles B, Lang A, Olff M. Complementary and integrative interventions for PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(2):2247888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junyue J, Siyu C, Xindong W, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for substance use disorders: a scientometric analysis and visualization of its use between 2001 and 2020. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12:722240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Björkman F, Ekblom Ö. Physical exercise as treatment for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mil Med. 2022;187(9–10):e1103-e1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadhakhan F, Lambert N, Middlebrook N, Evans DW, Falla D. Is exercise/physical activity effective at reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in adults A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology 2022:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiley ER, Seabrook JA, Gilliland JA, Anderson KK, Stranges S. Green space and substance use and addiction: a new frontier. Addict Behav. 2020;100:106155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiley ER, Stranges S, Gilliland JA, Anderson KK, Seabrook JA. Residential greenness and substance use among youth and young adults: associations with alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. Environ Res. 2022;212(A):113124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry MS, Repke MA, Metcalf AL, Jordan KE. Promoting healthy decision-making via natural environment exposure: initial evidence and future directions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engemann K, Pedersen CB, Arge L, Tsirogiannis C, Mortensen PB, Svenning JC. Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(11):5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran I, Sabol O, Mote J. The relationship between greenspace exposure and psychopathology symptoms: a systematic review. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2022;2(3):206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin L, Pahl S, White MP, May J. Natural environments and craving: the mediating role of negative affect. Health Place. 2019;58:102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin L, White MP, Pahl S, May J, Wheeler BW. Neighbourhood greenspace and smoking prevalence: results from a nationally representative survey in England. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jo H, Song C, Miyazaki Y. Physiological benefits of viewing nature: a systematic review of indoor experiments. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16(23):4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Wal AJ, Schade HM, Krabbendam L, van Vugt M. Do natural landscapes reduce future discounting in humans? Proc Biol Sci. 2013;280(1773):20132295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds L, Rogers O, Benford A, et al. Virtual nature as an intervention for reducing stress and improving mood in people with substance use disorder. J Addict. 2020;2020:1892390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson EO. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer FS, Frantz CM, Bruehlman-Senecal E, Dolliver K. Why is nature beneficial? the role of connectedness to nature. Environ Behav. 2009;41(5):607. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Block K, Molyneaux R, Gibbs L, et al. The role of the natural environment in disaster recovery: ‘We live here because we love the bush. Health Place. 2019;57:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westlund S. ‘Becoming human again’: Exploring connections between nature and recovery from stress and post-traumatic distress. Work. 2015;50(1):161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang M, Yang Y, Kim H, Jung S, Jin HY, Choi KH. The mechanisms of nature-based therapy on depression, anxiety, stress, and life satisfaction: examining mindfulness in a two-wave mediation model. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1330207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howell AJ, Dopko RL, Passmore HA, Buro K. Nature connectedness: associations with well-being and mindfulness. Pers Indiv Differ. 2011;51(2):166. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 1982;4(1):33-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Gordon W, Shonin E, Richardson M. Mindfulness and nature. Mindfulness. 2018;9(5):1655. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Djernis D, Lerstrup I, Poulsen D, Stigsdotter U, Dahlgaard J, O’Toole M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nature-based mindfulness: effects of moving mindfulness training into an outdoor natural setting. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16(17):3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaplan S. Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environ Behav. 2001;33(4):480-506. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotera Y, Rhodes C. Commentary: suggesting Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) for treating addiction. Addict Behav. 2020;111:106556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marchand WR, Klinger W, Block K, et al. Mindfulness-based therapeutic sailing for veterans with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Mil Med. 2022;187(3–4):e445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sudimac S, Sale V, Kühn S. How nature nurtures: amygdala activity decreases as the result of a one-hour walk in nature. Mol Psychiatr. 2022;27(11):4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taren AA, Gianaros PJ, Greco CM, et al. Mindfulness meditation training alters stress-related amygdala resting state functional connectivity: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. 2015;10(12):1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kral TRA, Schuyler BS, Mumford JA, Rosenkranz MA, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. Neuroimage. 2018;181:301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung M-K, Lau WKW, Chan CCH, Wong SSY, Fung ALC, Lee TMC. Meditation-induced neuroplastic changes in amygdala activity during negative affective processing. Soc Neurosci. 2018;13(3):277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crombie KM, Adams TG, Dunsmoor JE, et al. Aerobic exercise in the treatment of PTSD: an examination of preclinical and clinical laboratory findings, potential mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions. J Anxiety Disord. 2023;94:102680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Liu X. A systematic review of exercise intervention program for people with substance use disorder. Front Psychiatr. 2022;13:817927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ley C, Rato Barrio M, Koch A. ‘In the Sport I Am Here’: therapeutic processes and health effects of sport and exercise on PTSD. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(3):491-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hegberg NJ, Hayes JP, Hayes SM. Exercise intervention in PTSD: a narrative review and rationale for implementation. Front Psychiatr. 2019;10:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robertson CL, Ishibashi K, Chudzynski J, et al. Effect of exercise training on striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptors in methamphetamine users during behavioral treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(6):1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saanijoki T, Kantonen T, Pekkarinen L, et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with cerebral μ-opioid receptor activation in healthy humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54(7):1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brellenthin AG, Crombie KM, Hillard CJ, Brown RT, Koltyn KF. Psychological and endocannabinoid responses to aerobic exercise in substance use disorder patients. Subst Abuse. 2021;42(3):272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matei D, Trofin D, Iordan DA, et al. The endocannabinoid system and physical exercise. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Li R, Zhou C. Impact of physical exercise on substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noseworthy M, Peddie L, Buckler EJ, et al. The effects of outdoor versus indoor exercise on psychological health, physical health, and physical activity behaviour: a systematic review of longitudinal trials. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2023;20(3):1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calogiuri G, Nordtug H, Weydahl A. The potential of using exercise in nature as an intervention to enhance exercise behavior: results from a pilot study. Percept Mot Skills. 2015;121(2):350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calogiuri G, Evensen K, Weydahl A, et al. Green exercise as a workplace intervention to reduce job stress. Results from a pilot study. Work. 2015;53(1):99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lacharité-Lemieux M, Brunelle JP, Dionne IJ. Adherence to exercise and affective responses: comparison between outdoor and indoor training. Menopause. 2015;22(7):731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) . Community Engagement: An Essential Component of an Effective and Equitable Substance Use Prevention System. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP22-06-01-005. Rockville, MD: National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson M, Devlin AM, Pickering L, McCann M, Wight D. ‘It’s not 9 to 5 recovery’: the role of a recovery community in producing social bonds that support recovery. Drugs. 2021;28(5):475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM. Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(8):745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stanley IH, Hom MA, Chu C, et al. Perceptions of belongingness and social support attenuate PTSD symptom severity among firefighters: a multistudy investigation. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(4):543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johansen VA, Milde AM, Nilsen RM, et al. The relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms after exposure to physical assault: an 8 years longitudinal study. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(9–10):NP7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward KS, Truong S, Gray T. Connecting to nature through community engaged scholarship: community gardens as sites for collaborative relationships, psychological, and physiological wellbeing. Front Psychiatr. 2022;13:883817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boffi M, Pola L, Fumagalli N, Fermani E, Senes G, Inghilleri P. Nature experiences of older people for active ageing: an interdisciplinary approach to the co-design of community gardens. Front Psychol. 2021;12:702525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panțiru I, Ronaldson A, Sima N, Dregan A, Sima R. The impact of gardening on well-being, mental health, and quality of life: an umbrella review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2024;13(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun Q, Loveday M, Nwe S, Morris N, Boxall E. Green social prescribing in practice: a case study of Walsall, UK. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2023;20(17):6708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sirisena M, Cheetham M. You’re sort of building community in a bigger way’: Exploring the potential of creative, nature-based activities to facilitate community connections. Arts Health 2024;25:1-16. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2024.2319666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Besterman-Dahan K, Hathaway WA, Chavez M, et al. Multisite agricultural Veterans Affairs farming and recovery mental health services (VA FARMS) pilot program: protocol for a responsive mixed methods evaluation study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12:e40496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kitzinger RH, Jr., Gardner JA, Moran M, et al. Habits and routines of adults in early recovery from substance use disorder: clinical and research implications from a mixed methodology exploratory study. Subst Abuse. 2023;17:11782218231153843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McKay JR. Making the hard work of recovery more attractive for those with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2017;112(5):751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andrabi N, Khoddam R, Leventhal AM. Socioeconomic disparities in adolescent substance use: role of enjoyable alternative substance-free activities. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leventhal AM, Bello MS, Unger JB, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, Audrain-McGovern J. Diminished alternative reinforcement as a mechanism underlying socioeconomic disparities in adolescent substance use. Prev Med. 2015;80:75-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Correia CJ, Carey KB, Simons J, Borsari BE. Relationships between binge drinking and substance-free reinforcement in a sample of college studentsApreliminaryinvestigation. Addict Behav. 2003;28(2):361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meshesha LZ, Magri TD, Braun TD, et al. Patient perspective on the role of substance-free activities during alcohol use disorder treatment: a mixed-method study. Alcohol Treat Q. 2023;41(3):309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang L, Bonanno GA, Hougen C, Hobfoll SE, Hou WK. Everyday life experiences for evaluating post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(2):2238584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Benvegnù G, Semenzato M, Urbani A, Zanlorenzi I, Cibin M, Chiamulera C. Nature-based experience in Venetian Lagoon: effects on craving and wellbeing in addict residential inpatients. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1356446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dai CL, Chen CC, Richardson GB, Gordon HRD. Managing substance use disorder through a walking/running training program. Subst Abuse. 2020;14:1178221820936681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bennett LW, Cardone S, Jarczyk J. Effects of a therapeutic camping program on addiction recovery. The algonquin haymarket relapse prevention program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1998;15(5):469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marchand WR, Klinger W, Block K, et al. Safety and psychological impact of sailing adventure therapy among Veterans with substance use disorders. Med. 2018;40:42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Littman AJ, Bratman GN, Lehavot K, et al. Nature versus urban hiking for Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot randomised trial conducted in the Pacific Northwest USA. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e051885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Achabaeva AB, Hassani H, Dzhambekova ZM, et al. [Natural healing factors of Nalchik resort in medical rehabilitation of the patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. (randomized controlled trial)]. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kul’t. 2023;100(6):59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bichler CS, Niedermeier M, Hüfner K, et al. Climbing as an add-on treatment option for patients with severe anxiety disorders and PTSD: feasibility analysis and first results of a randomized controlled longitudinal clinical pilot trial. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19(18):11622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bettmann JE, Prince KC, Ganesh K, et al. The effect of time outdoors on veterans receiving treatment for PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2021;77(9):2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koziel N, Vigod S, Price J, Leung J, Hensel J. Walking psychotherapy as a Health Promotion strategy to improve mental and physical health for patients and therapists: clinical open-label feasibility trial. Can J Psychiatr. 2022;67(2):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zabag R, Deri O, Gilboa-Schechtman E, Richter-Levin G, Levy-Gigi E. Cognitive flexibility in PTSD individuals following nature adventure intervention: is it really that good? Stress. 2020;23(1):97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gelkopf M, Hasson-Ohayon I, Bikman M, Kravetz S. Nature adventure rehabilitation for combat-related posttraumatic chronic stress disorder: a randomized control trial. Psychiatr Res. 2013;209(3):485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rogers CM, Mallinson T, Peppers D. High-intensity sports for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression: feasibility study of ocean therapy with veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(4):395-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Daniel Dustin NB, Arave J, Wall W, Wendt G. The promise of river running as a therapeutic medium for veterans coping with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Ther Recreat J. 2011;45(4):326. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Poulsen DV, Stigsdotter UK, Djernis D, Sidenius U. ‘Everything just seems much more right in nature’: how veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder experience nature-based activities in a forest therapy garden. Health Psychol Open. 2016;3(1):2055102916637090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perry DJ, Crawford SL, Mackin JM, Averka JJ, Smelson DA. The feasibility of wildlife immersion experiences for Veterans with PTSD. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1290668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Detweiler MB, Self JA, Lane S, et al. Horticultural therapy: a pilot study on modulating cortisol levels and indices of substance craving, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and quality of life in veterans. Alternative Ther Health Med. 2015;21(4):36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vella EJ, Milligan B, Bennett JL. Participation in outdoor recreation program predicts improved psychosocial well-being among veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Mil Med. 2013;178(3):254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wheeler M, Cooper NR, Andrews L, et al. Outdoor recreational activity experiences improve psychological wellbeing of military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: positive findings from a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walter KH, Otis NP, Hose MK, Ober KM, Glassman LH. The effectiveness of the National Veterans Summer Sports Clinic for veterans with probable posttraumatic stress disorder. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1207633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maier J, Jette S. Promoting nature-based activity for people with mental illness through the US ‘Exercise Is Medicine’ initiative. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]