Abstract

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain is a significant public health concern in Europe. With the advent of the digital age, online health information-seeking behaviour has become increasingly important, influencing health outcomes and the ability of individuals to make well-informed decisions regarding their own well-being or of those they are responsible for. This study protocol outlines an investigation into how individuals in five European countries (Austria, Denmark, Ireland, Italy, and Spain) seek online health information for musculoskeletal pain.

Methods

The protocol adopts an exploratory and systematic two-phase approach to analyse online health information-seeking behaviour. Phase 1 involves four steps: (1) extraction of an extensive list of keywords using Google Ads Keyword Planner; (2) refinement of the list of keywords by an expert panel; (3) investigation of related topics and queries and their degree of association with keywords using Google Trends; and (4) creation of visual representations (word clouds and simplified network graphs) using R. These visual representations provide insights into how individuals search for online health information for musculoskeletal pain. Phase 2 identifies relevant online sources by conducting platform-specific searches on Google, X, Facebook, and Instagram using the refined list of keywords. These sources are then analysed and categorised with NVivo and R to understand the types of information that individuals encounter.

Conclusions

This innovative protocol has significant potential to advance the state-of-the-art in digital health literacy and musculoskeletal pain through a comprehensive understanding of online health information-seeking behaviour. The results may enable the development of effective online health resources and interventions.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal pain, digital health, information-seeking behaviour, health literacy, health communication, Internet, social media

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain affects approximately 1.7 billion people worldwide, representing a significant global public health concern with far-reaching implications. 1 Within Europe, the burden of musculoskeletal pain is particularly noteworthy, 2 consistently ranking among the top contributors to non-communicable disease-related morbidity in the region. 3 For individuals, the impact of musculoskeletal pain extends beyond physical discomfort to encompass reduced quality of life, restricted mobility, and impaired daily functioning, jeopardizing overall well-being.4,5 For healthcare systems, musculoskeletal pain presents a substantial financial burden, accounting for a significant share of healthcare utilization. 6 Additionally, European societies bear the weight of indirect costs, including lost workdays and reduced productivity among workers. 6 Addressing musculoskeletal pain effectively requires not only efficient clinical management but also the implementation of prevention and health promotion strategies. 7 Given the escalating magnitude of the problem and the lack of prospective improvement, 8 it is imperative to explore new interventions and preventative strategies to overcome these challenges.

Considering these challenges, digital health literacy emerges as a critical tool in the current management of musculoskeletal pain. Defined as the ability to access, understand, evaluate, and apply digital health information for informed decision-making, 9 digital health literacy has gained increasing importance for both health professionals and the general public, offering a significant impact on the field of musculoskeletal pain. This issue is particularly relevant in the European Union, where over 80% of inhabitants are active internet users, and more than 50% seek related information online.9,10 The rapid proliferation of internet-based health information resources and the evolving landscape of social media platforms have transformed how both health professionals and the general public seek, consume, and share health-related information. 11 However, several studies show that freely accessible musculoskeletal pain online sources demonstrate low credibility standards, provide mostly inaccurate information, and lack comprehensiveness.12–15 The implications extend beyond mere knowledge acquisition, directly influencing health outcomes and the ability of individuals to make well-informed decisions regarding their own well-being or of those they are responsible for. 9 Thus, understanding how individuals navigate this intricate digital landscape is important for enhancing health outcomes and ensuring informed decision-making.

This article outlines a research study protocol designed to investigate online health information-seeking behaviour, a pivotal component of digital health literacy, for musculoskeletal pain. Online health information-seeking ‘refers to individuals using the internet to search for information about their health, risks, illnesses, and health-protective behaviours’. 16 While this topic is a vast field with numerous knowledge gaps,17–22 this study protocol proposes an exploratory and systematic approach to pursue the following specific objectives:

Identify common and relevant keywords used in online searches for musculoskeletal pain content.

Identify and characterise the most searched online sources of musculoskeletal pain content, using the refined keywords from objective 1.

This study protocol is part of the Innovation Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health Literacy in the Digital Era (Digi4MSK), a project funded by the European Union within the Erasmus + Programme. The results obtained from this protocol will underpin a future study aimed at assessing the quality of online health information for musculoskeletal pain, and developing targeted and impactful materials and online resources for both health professionals and the general public. In summary, the anticipated findings from this study are poised to shape interventions aimed at enhancing the accessibility, credibility, and comprehensiveness of online health information in musculoskeletal pain. This, in turn, contributes to advancing the state-of-the-art in digital health literacy and offers practical insights for both the management and prevention of musculoskeletal pain. Additionally, beyond its immediate impact, this protocol could assist fellow researchers in musculoskeletal pain and other related domains, providing a blueprint for replication and methodological enhancement.

Methods

The proposed method adopts an exploratory and systematic approach. This way, it enables an investigation of the online health information-seeking behaviour of individuals seeking musculoskeletal pain content. The scope of this protocol embraces the linguistic and cultural diversity of the study population because these aspects greatly influence how individuals search for, and engage with, online health information. Considering the Digi4MSK project, it encompasses five European countries and their respective main languages: Ireland (English), Spain (Spanish), Austria (German), Italy (Italian), and Denmark (Danish), alongside English for each country, which is a widely spoken language in Europe.23,24 Therefore, the methods will be reproduced in the language of each country, enabling individual analyses and a combined overall analysis.

To ensure rigor and comprehensiveness, a panel of at least ten experts with proven relevant background in musculoskeletal pain and digital health literacy will be purposively assembled. These experts will be selected based on their qualifications, experience, and regional knowledge relevant to the participating countries. There will be a similar number of experts from each participating country to ensure adequate local expertise. Inclusion criteria are a minimum of five years of experience in the field of musculoskeletal pain and/or digital health literacy (i.e. clinical or research experience); possession of an advanced degree (e.g. master's and doctorate) in relevant fields of health sciences such as medicine, physiotherapy, psychology, nursing, public health, or health informatics; being fluent in the local language (e.g. German in Austria); and residing in the country where the study is being conducted. Participants of the expert panel will be recruited both from within the Digi4MSK project consortium and through the invitation of external experts, leveraging the extensive network of the European Pain Federation (EFIC) as a project partner. Initially, three experts per country will be invited to participate and if no response is received within a week, a fourth expert will be contacted, ensuring a minimum of two experts per country and reaching the preset minimum of ten experts overall. Invitations will be conducted primarily via e-mail followed by the informed consent form. In accordance with the ICMJE authorship recommendations, 25 these experts may be offered the non-binding opportunity for co-authorship in future publications arising from this study. Additionally, due to their own and shared experience with pain, at least one person living with musculoskeletal pain per country will be invited to join the experts panel and participate in the same activities as the experts. People self-reporting persistent musculoskeletal pain for at least three months will be considered for inclusion, regardless of treatment status. They will be identified and recruited through the existing networks of research institutions in each country of the Digi4MSK consortium.

The expert panel will provide essential insights into the relevance of identified keywords from online searches for musculoskeletal pain and contribute to the characterization of the most frequently searched online sources. The panel will be overseen and coordinated by investigators from the Digi4MSK project. Procedures are designed to facilitate the participation and engagement of the expert panel. Their work will primarily occur online through asynchronous collaboration and consensus-based decision-making, using cloud-based spreadsheets. To standardize actions across different study phases, written tutorials with clear instructions will be provided via email, ensuring that each panel decision is accompanied by expert comments for justification. Asynchronous participation was chosen to promote full involvement and ensure smooth progression of the study phases, as synchronous meetings require calendar alignment and are prone to disruption by unforeseen events. Deadlines will be set to achieve the objectives at each step of every phase and to allow the experts to manage their time flexibility.

The expert panel's activities are further detailed next, within the study design description, comprising of two distinct and sequential phases, each focusing on specific research objectives. Table 1 summarizes the different phases, steps, and their methods and outputs.

Table 1.

Summary of the different phases and steps of this study and their methods and expected outputs.

| Phase | Step | Methods | Expected outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (keywords) | 1 | a. Definition of the primary list of keywords. (Expert Panel) b. Expansion of the primary list of keywords using Google Ads Keyword Planner to identify frequently searched keywords. (Study Investigators) |

Expanded list of keywords |

| 2 | Curation of the expanded list based on relevance and specificity. (Expert Panel) | Refined list of keywords | |

| 3 | Identification of related topics and queries associated with the refined list of keywords using Google Trends. (Study Investigators) | a. Related topics b. Related queries c. Their normalised degree of association with the keywords. |

|

| 4 | Creation of visual representations based on the refined list of keywords and related topics/queries and their degree of association using R. (Study Investigators) | a. Word clouds b. Simplified network graphs |

|

| 2 (sources) | N/A | a. Conduction of platform-specific (Google, X, Facebook, Instagram) searches using the refined list of keywords to identify relevant sources. (Expert Panel) b. Characterisation of sources based on deductive and inducive methods using NVivo for qualitative content analysis and R for descriptive statistics. (Study Investigators) |

a. List of selected online sources b. Characterization of selected online sources |

Several tools will be used to perform these methods and achieve the expected outputs. Table 2 summarizes these tools and their application in this study.

Table 2.

Summary of the tools used and their application in this study.

| Tool | Company | Application in the study |

|---|---|---|

| Google Ads Keyword Planner 26 | Google LLC | Expand the keyword list by identifying frequently searched terms for musculoskeletal pain. |

| R 27 | R Core Team | Generate visual representations (word clouds and simplified network graphs) and perform descriptive statistics analysis. |

| NVivo 28 | QSR International | Conduct qualitative content analysis and characterise selected online sources. |

Phase 1: Identifying the most used and relevant keywords

This phase aims to identify the most used and relevant keywords for musculoskeletal pain online content search, encompassing four steps:

First step: Extracting an expanded list of keywords

This preliminary step will provide an expanded list of keywords used by individuals in online searches about musculoskeletal pain. Initially, the expert panel will be asked to provide a primary list of keywords associated with ‘musculoskeletal pain’, ‘musculoskeletal pain disorders’, or ‘musculoskeletal health’. This list should have from five to 10 keywords in each language (local and English) for each country. These keywords are expected to be in line with the prevalent musculoskeletal conditions in society, such as low back pain, neck pain, shoulder pain, knee osteoarthritis, among others.29–31 However, the experts will also be allowed to propose keywords from their own experience that are aligned with this study's objectives (i.e. musculoskeletal pain online health information). Each expert will provide a list of keywords that will be combined with the lists from other panellists and a consensus will be reached on which keywords will compose the final primary list of keywords. Specifically, all the words will be combined into a single list and the panellists will vote hierarchically on the ten most relevant terms, avoiding redundancies and overlaps, and provide commentary to justify their choices. Keywords receiving unanimous support (i.e. in the top ten ranking of all panellists) will be automatically selected, while those receiving at least two-thirds of support will undergo a second round of voting. The entire process, including excluded words, will be reported as Supplemental Material.

Then, based on previous studies,32,33 a general inquiry using Google Ads Keyword Planner will be employed by the study investigators to identify frequently searched keywords associated with the primary list of keywords. This tool allows users to enter specific keywords, phrases, or website URLs, to generate data on search volume, competition, and cost-per-click estimates for those keywords. 26 Therefore, it helps the selection of the most effective keywords for advertising or research purposes. From the outputs of the tool, only keywords with average monthly searches in the past 24 months above the median will be included in the final expanded list of keywords. This initial selection enables the manual refinement to be conducted by the expert panel in the next step.

Second step: Refining a refined list of keywords with expert panel guidance

This critical step will provide a refined list of keywords. The expert panel will refine the expanded list of keywords extracted from the Google Ads Keyword Planner based on the criteria of relevance, specificity, and alignment with the objectives of this research study. This process ensures that the keywords more accurately represent the terms used by individuals when searching for health information for musculoskeletal pain, encompassing both medical terminology and layman's terms. The panel will also eliminate less relevant terms and merge redundant terms, resulting in a final list that is both meaningful and conducive to high-quality data collection. By leveraging the expertise of the panel in selecting and refining the keywords, this step enhances the validity of the study and its ability to provide practical insights into online health information-seeking behaviour in the context of musculoskeletal pain.

Third step: Investigating related topics and related queries

This step will provide a list of related topics and related queries associated with the refined list of keywords, and the degree of their association based on a normalised measurement provided by Google Trends. A systematic analysis will be conducted using this tool, enabling deeper insights into the keywords and their usage patterns.32,34 Google Trends is an online tool that provides valuable insights into internet search trends: the interest of a search term over time, the interest by geographical sub-region, the related topics, and the related queries. 35 Instead of showing absolute frequency numbers, the tool normalises the data and shows the relative search volume (a proxy of interest over the keyword) on a scale of 0 to 100, in which 100 is the maximum popularity. 36 Moreover, related topics refer to subjects or themes that are often explored alongside the input keyword, revealing a broader context of information. Related queries, however, are specific search terms that individuals frequently use in conjunction with the input keyword. These related queries offer a glimpse into the specific questions or issues that are of interest to users searching for information on the topic. By leveraging Google Trends, this research aims to expand the understanding of online health information-seeking behaviour for musculoskeletal pain.

Fourth step: Generating word clouds and simplified network graphs

This final step of Phase 1 will generate a visual representation using word clouds and simplified network graphs, synthesising the outputs from Phase 1 of this research study to enable better data analysis. In this manner, this step will provide a well-rounded view of the refined list of keywords and their association with related queries and related topics. These visual representations will be created with R, a programming language and environment widely used for data analysis, visualization, and statistical modelling. 27 Word clouds visually depict the frequency of the items from the refined list keywords (from the second step). In these word clouds, the size of individual keywords corresponds to their frequency in internet searches 37 ; therefore, larger keywords represent keywords more frequently searched online. Word clouds (Figure 1) serve as a valuable tool for visually identifying the most common and frequently explored subjects.

Figure 1.

Example of a word cloud.

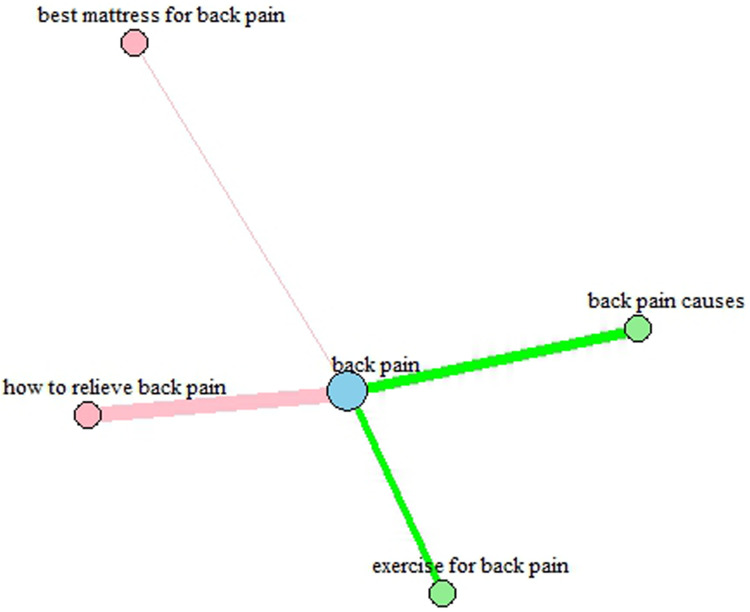

Simplified network graphs will offer a more detailed exploration of the relationships between the items from the refined list of keywords, related queries, and related topics. Central nodes within the network graph represent the keywords. Lines (edges) within the graph illustrate the strength and frequency of associations between the central keywords and related queries and related topics. The use of network graphs (Figure 2) facilitates an exploration of the context in which the keywords are used, providing deeper insights into search patterns, trends, and the broader information landscape for musculoskeletal pain. 38

Figure 2.

Example of a simplified network graph.

Phase 2: Determining and characterising a sample of the most visited and relevant sources

In the second phase, the research focus shifts from keywords towards sources of online health information for musculoskeletal pain, to determine a sample of the most frequently visited, and relevant, of them. The results from this phase will consist of a list of selected sources with their characterisation, which will serve as the foundation for the analysis of online health information-seeking behaviour in musculoskeletal pain. This phase employs a cross-platform research approach, investigating various prominent online platforms well-acknowledged for their roles in disseminating online health information. The platforms under this protocol include the Google search engine, X (former Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram, each playing a pivotal role in disseminating health-related content and digital discourse.

Inspired by previous studies, 32 the sampling method consists of identifying and selecting the top search results (results that appear in the top positions on a search engine results page, such as Google, when a person enters specific terms or keywords) using the refined list of keywords (from Phase 1) in each of the aforementioned platforms. The cross-platform search will be conducted by the expert panel members in their corresponding country-language combinations to ensure that the results are aligned with local searches; therefore, considering the platforms’ algorithms. To prevent avoidable selection bias, incognito mode will be used and, in the case of social media platforms, newly set-up accounts (without any previous use) will be adopted for performing the searches. At least two expert panel members, each one in a different IP location in their country, will independently perform cross-platform searches. Due to the search algorithm of these platforms, it is not uncommon that two different users, even in the same country, to obtain different results. For that reason, only top search results that are common for both (or more) members will be included in the final sample. Individual searches for each keyword from the refined list of keywords will be performed by the expert panel members. For each keyword, the first source that appears among the top search results for two or more expert panel members in each platform will be included in the final sample. Exclusion criteria will be applied to sources that do not meet the array of location-language requirements of the study: English in Ireland and every participating country, Spanish in Spain, German in Austria, Italian in Italy, and Danish in Denmark.

The identified sources will be characterised based on publicly available information. The characterisation will follow both inductive and deductive methods. Based on previous internet and social media research,39–42 the study expects to include the following variables when data is available and appropriate: engagement metrics (such as likes, comments, shares, and number of views); self-identification or apparent authorship type (health professional digital influencer, non-health professional digital influencer, non-digital influencer individuals, healthcare organization, educational organizations, media organizations, governmental bodies, and other organizations); apparently intended audience (general public, healthcare professionals, researchers, and organizations); apparently intended purposes (educational, commercial, etc.); and content type (risk factors, prevention, treatment, and biography). The variables and categories can be adapted and expanded throughout the research with the support of the qualitative data and the current literature. 43 All major decisions taken during the coding process will be recorded to ensure transparency and reproducibility. 43 Qualitative content analysis will be conducted using NVivo, 28 facilitating efficient coding, while quantitative data analysis will rely on R for descriptive statistics. 44

Overall, the data analysis process will be iterative and exploratory, aiming to uncover insights into online health information-seeking behaviour for musculoskeletal pain across diverse European linguistic and cultural contexts. The integration of quantitative and qualitative approaches will provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under investigation.

Data management

Data management within this research study diligently upholds the FAIR principles 45 (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable), ensuring the integrity of the research process. This research is also grounded in the principles of Open Science, 46 emphasizing transparency, collaboration, and the dissemination of knowledge within the scientific community. Upon the conclusion of the study, de-identified data will be shared through a suitable repository, Zenodo, 47 thereby allowing fellow researchers to validate and expand upon the findings. The data management process for this research will be facilitated through cloud-based services provided by Google, ensuring efficient storage, accessibility, and collaboration. Specifically, data will be securely stored and organized using Google Drive, allowing authorized team members to access and manage research materials, datasets, and documents with ease. Google Docs and Google Sheets will be employed for manual data collection and the maintenance of raw databases, providing an integrated and user-friendly environment for research materials and datasets.

Discussion

This protocol is expected to lead to several findings that will contribute to a better understanding of the online health information-seeking behaviour in musculoskeletal pain across Europe. The different study phases are designed to provide insights that are complementary to each other. In Phase 1, the analysis of the most common and relevant keywords is expected to reveal a wide range of terms that may have an impact on the development of more effective online health resources. By recognizing the terminology preferences through several countries and languages, these resources can be tailored to provide more accessible and relevant information to healthcare professionals, healthcare users, and the general public. In Phase 2, the identification of the most frequently visited and relevant sources across various digital platforms is expected to reveal distinctive nuances in online musculoskeletal pain content. This sample of online sources can be used in several ways; for instance, the Digi4MSK project expects to further evaluate their quality and reliability in future endeavours. Altogether, these outcomes may underpin strategies that can aid healthcare provider-user communication, inform healthcare policies, and foster the development of interventions aimed at improving online health information-seeking behaviour in relation to musculoskeletal pain content.

While these outcomes are anticipated, it is essential to acknowledge potential limitations in this research. This research study limits data collection on search engines to Google and social media platforms to X, Facebook, and Instagram. Future research can study how similar methods perform using other search engines (e.g. Bing) or social media platforms (e.g. YouTube and TikTok). Moreover, this research study considers the main languages (and English) in the studied countries, which may exclude important data from displaced, migrant, or cultural minority communities, such as those from Ukraine and Syria. Due to resource constraints, this research team is not able to perform such an inclusive study, but it is recommended for future research to broaden the methodology or to specifically study these country-language limitations. Similarly, this protocol does not include an analysis of the quality and credibility of the sources obtained in phase 2. However, such assessments are encouraged in subsequent studies. By acknowledging these potential limitations, this study aims to uphold transparency and integrity within our research.

Conclusion

This innovative protocol presents the first investigation into online health information-seeking behaviour particularly related to musculoskeletal pain across diverse European contexts. By examining the most relevant and frequently used keywords, and the most visited online sources originating from cross-platform searches based on these keywords, this study aims to provide a better understanding of how individuals search for, and engage with, musculoskeletal pain information online. The insights gained are expected to inform the development of more effective online health resources, improve healthcare provider-user communication, and influence healthcare policies. Future research should address the limitations outlined and explore additional dimensions of online health information-seeking behaviour, particularly among diverse and underserved populations. Overall, this research holds significant potential to advance digital health literacy and contribute to the broader field of musculoskeletal health research.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241298480 for Exploring online health information-seeking behaviour for musculoskeletal pain in Europe: A study protocol combining expert panel insights with search trends on social media and Google by Lucas Cardoso da Silva, Kieran O’Sullivan, Lara Coyne, Thorvaldur Skuli Palsson, Steffan Wittrup McPhee Christensen, Morten Hoegh, Mary O’Keeffe, Francesco Langella and Julia Blasco-Abadía, Pablo Bellosta-Lopéz, Víctor Doménech-García in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleague Romana Hessler for language-proofing and reviewing the manuscript writing.

Footnotes

Contributorship: LCS, PBL, and VDG researched the literature and conceived the study. LCS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors supported the conceptualization, reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at San Jorge University (N117/1/23-24). This research study incorporates ethical considerations and adheres to established ethical guidelines and practices. Informed consent will be obtained from the expert panel participants. This study poses minimal risk to individuals, but steps are taken to avoid potential harm. For instance, Phase 2 will provide data that may include personally identifiable information (particularly from social media posts); therefore, it will be anonymized, ensuring that individuals or organizations in publicly available internet data cannot be identified. Moreover, the study adheres to all relevant legal and ethical standards in the countries where data is collected. This includes respecting local regulations regarding both data protection and ethical research conduct.

Funding: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. ERASMUS-EDU-2022-PI-ALL-INNO: Project n.101111708. JBA is supported by the Grant PIF 2022–2026 from ‘Gobierno de Aragón’. JBA, PBL, and VDG are members of the research group MOTUS supported by ‘Gobierno de Aragón’ (n. B60_23D). The funders did not have any role in this study.

Guarantor: PBL and VDG.

ORCID iD: Lucas Cardoso da Silva https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3841-6055

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Gill TK, Mittinty MM, March LM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of other musculoskeletal disorders, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol [Internet] 2023. Nov [cited 2024 May 8]; 5: e670–e682. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2665991323002321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safiri S, Kolahi A, Cross M, et al. Prevalence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years due to musculoskeletal disorders for 195 countries and territories 1990–2017. Arthritis Rheumatol [Internet]. 2021. Apr [cited 2023 Oct 31];73:702–714. Available from: https://acrjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41571 doi: 10.1002/art.41571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov Ket al. et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the global burden of disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020. Dec [cited 2023 Oct 31];396(10267):2006–17. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673620323400 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32340-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.March L, Smith EUR, Hoy DG, et al. Burden of disability due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol [Internet]. 2014. Jun [cited 2023 Oct 31];28:353–366. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1521694214000825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf AD. Musculoskeletal pain in Europe: its impact and a comparison of population and medical perceptions of treatment in eight European countries. Ann Rheum Dis [Internet]. 2004. Apr 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];63:342–347. Available from: https://ard.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/ard.2003.010223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevan S. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol [Internet]. 2015. Jun [cited 2023 Oct 31];29:356–373. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1521694215000947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis R, Gómez Álvarez CB, Rayman M, et al. Strategies for optimising musculoskeletal health in the 21st century. BMC Musculoskelet Disord [Internet] 2019. Dec [cited 2023 Oct 31]; 20: 164. Available from: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-019-2510-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira ML, De Luca K, Haile LM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol [Internet] 2023. Jun [cited 2024 Jan 23]; 5: e316–e329. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S266599132300098X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Kessel R, Wong BLH, Clemens T, et al. Digital health literacy as a super determinant of health: more than simply the sum of its parts. Internet Interv [Internet] 2022. Mar [cited 2023 Oct 31]; 27: 100500. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214782922000070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Commission. Statistical office of the European Union. Digital society statistics at regional level. In: Eurostat regional yearbook: 2023 ed [Internet]. LU: Publications Office, 2023, pp.103–109 [cited 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Digital_society_statistics_at_regional_level#Internet_users [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sieck CJ, Sheon A, Ancker JS, et al. Digital inclusion as a social determinant of health. NPJ Digit Med 2021. Mar 17; 4: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira G, Traeger AC, Machado G, et al. Credibility, accuracy, and comprehensiveness of internet-based information about low back pain: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res [Internet] 2019. May 7 [cited 2024 Jan 24]; 21: e13357. Available from: https://www.jmir.org/2019/5/e13357/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silberg WM. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: caveant lector et viewor–let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA J Am Med Assoc [Internet]. 1997. Apr 16 [cited 2024 Jan 24];277:1244–1245. Available from: http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/doi/10.1001/jama.277.15.1244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos RP, Alonso TP, Correia IMTet al. et al. Patients should not rely on low back pain information from Brazilian official websites: a mixed-methods review. Braz J Phys Ther [Internet]. 2022. Jan [cited 2024 Jan 24];26:100389. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1413355521001180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goff AJ, Barton CJ, Merolli M, et al. Comprehensiveness, accuracy, quality, credibility and readability of online information about knee osteoarthritis. Health Inf Manag J [Internet] 2023. Sep [cited 2024 Jan 24]; 52: 185–193. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/18333583221090579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma X, Liu Y, Zhang P, et al. Understanding online health information seeking behavior of older adults: a social cognitive perspective. Front Public Health [Internet] 2023. Mar 3 [cited 2023 Nov 14]; 11: 1147789. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1147789/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira BH, Hyppolito IMD, Malheiros Zet al. et al. Information-seeking behaviors and barriers to the incorporation of scientific evidence into clinical practice: a survey with Brazilian dentists. Menezes RG, editor. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2021. Mar 25 [cited 2023 Nov 14];16:e0249260. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Chung S, Shi Wet al. et al. Online health information-seeking behaviours and eHealth literacy among first-generation Chinese immigrants. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2023. Feb 16 [cited 2023 Nov 14];20:3474. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/4/3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D, Zhan W, Zheng C, et al. Online health information-seeking behaviors and skills of Chinese college students. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021. Dec [cited 2023 Nov 14];21:736. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-10801-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaveet E, Urquhart C, Gallegos Met al. et al. Web-based health information-seeking methods and time since provider engagement: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res [Internet]. 2022. Nov 30 [cited 2023 Nov 14];6:e42126. Available from: https://formative.jmir.org/2022/11/e42126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akakpo MG. The role of care-seeking behavior and patient communication pattern in online health information-seeking behavior – a cross-sectional survey. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2023 Nov 14];42. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/42/124/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu ZW. Research progress and model construction for online health information seeking behavior. Front Res Metr Anal [Internet]. 2022. Feb 11, p.14 [cited 2024 Jan 26]; 7: 706164. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frma.2021.706164/full doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.706164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seidlhofer B, Breiteneder A, Pitzl ML. English as a Lingua Franca in Europe: challenges for applied linguistics. Annu Rev Appl Linguist [Internet]. 2006. Jan [cited 2024 May 14];26. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S026719050600002X [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labrie N, Quell C. Your language, my language or English? The potential language choice in communication among nationals of the European Union. World Englishes [Internet]. 1997. Mar [cited 2024 May 14]; 16: 3–26. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-971X.00043. [Google Scholar]

- 25.ICMJE. Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors [Internet]. 2024. [cited 2024 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html

- 26.Google. How to Use the Keyword Planner Tool – Google Ads [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2023 Nov 2]. Available from: https://ads.google.com/home/resources/using-google-ads-keyword-planner/

- 27.R: The R Project for Statistical Computing [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/

- 28.Jackson K, Bazeley P. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo, 3rd ed. Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington, DC Melbourne: Sage, 2019. p.349. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis [Internet]. 1998. Nov 1 [cited 2023 Nov 7];57:649–655. Available from: https://ard.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/ard.57.11.649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorce P, Jacquier-Bret J. Global prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among physiotherapists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord [Internet]. 2023. Apr 4 [cited 2023 Nov 7];24:265. Available from: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-023-06345-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. Musculoskeletal health [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2023 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions

- 32.Yamaguchi Y, Lee D, Nagai T, et al. Googling musculoskeletal-related pain and ranking of medical associations’ patient information pages: google ads keyword planner analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020. Aug 14; 22: e18684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berr K, Tizek L, Schielein MC, et al. Analyzing web searches for axial spondyloarthritis in Germany: a novel approach to exploring interests and unmet needs. Rheumatol Int [Internet]. 2023. Jan 14 [cited 2023 Nov 2];43:1111–1119. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00296-023-05273-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telfer S, Woodburn J. Let me Google that for you: a time series analysis of seasonality in internet search trends for terms related to foot and ankle pain. J Foot Ankle Res [Internet]. 2015. Dec [cited 2023 Oct 27];8:27. Available from: https://jfootankleres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13047-015-0074-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Google. FAQ about Google Trends data - Trends Help [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2023 Nov 3]. Available from: https://support.google.com/trends/answer/4365533?hl=en

- 36.Kardeş S, Erdem A, Gürdal H. Public interest in musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: infodemiology study. Z Für Rheumatol [Internet]. 2022. Apr [cited 2023 Oct 27];81:247–252. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00393-021-00989-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DePaolo CA, Wilkinson K. Get your head into the clouds: using word clouds for analyzing qualitative assessment data. TechTrends [Internet]. 2014. May [cited 2023 Nov 3];58:38–44. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11528-014-0750-9 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pokorny JJ, Norman A, Zanesco APet al. et al. Network analysis for the visualization and analysis of qualitative data. Psychol Methods [Internet]. 2018. Mar [cited 2023 Nov 3];23:169–183. Available from: https://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/met0000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safdari R, Gholamzadeh M, Saeedi S, et al. An evaluation of the quality of COVID-19 websites in terms of HON principles and using DISCERN tool. Health Inf Libr J [Internet].2022. Aug 10 [cited 2023 Oct 27],40: hir.12454. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hir.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bethell MA, Anastasio AT, Taylor JR, et al. Evaluating the distribution, quality, and educational value of videos related to shoulder instability exercises on the social media platform TikTok. JAAOS Glob Res Rev [Internet] 2023. Jun [cited 2023 Oct 27]; 7: 2–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Information on Instagram: content analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2021. Jul 27; 7: e23876. doi: 10.2196/23876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomaa B, Houghton RF, Crocker Net al. et al. Skin cancer narratives on Instagram: content analysis. JMIR Infodemiology [Internet]. 2022. Jun 2 [cited 2023 Oct 27];2:e34940. Available from: https://infodemiology.jmir.org/2022/1/e34940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 4th ed. Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Boston: Sage, 2015, p.431. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao P. Working with Data in Public Health: a practical pathway with R [Internet], Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-99-0135-7 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, IjJ Aalbersberg, et al. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship . Sci Data [Internet]. 2016. Mar 15 [cited 2023 Nov 7];3:160018. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata201618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vicente-Saez R, Martinez-Fuentes C. Open science now: a systematic literature review for an integrated definition. J Bus Res [Internet]. 2018. Jul [cited 2023 Nov 7];88:428–436. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0148296317305441 [Google Scholar]

- 47. European Organization for Nuclear Research, OpenAIRE. Zenodo: Research. Shared. [Internet]. CERN; 2013 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.zenodo.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- European Organization for Nuclear Research, OpenAIRE. Zenodo: Research. Shared. [Internet]. CERN; 2013 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.zenodo.org/

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241298480 for Exploring online health information-seeking behaviour for musculoskeletal pain in Europe: A study protocol combining expert panel insights with search trends on social media and Google by Lucas Cardoso da Silva, Kieran O’Sullivan, Lara Coyne, Thorvaldur Skuli Palsson, Steffan Wittrup McPhee Christensen, Morten Hoegh, Mary O’Keeffe, Francesco Langella and Julia Blasco-Abadía, Pablo Bellosta-Lopéz, Víctor Doménech-García in DIGITAL HEALTH