Abstract

Objective

To construct a highly accurate and interpretable feeding intolerance (FI) risk prediction model for preterm newborns based on machine learning (ML) to assist medical staff in clinical diagnosis.

Methods

In this study, a sample of 350 hospitalized preterm newborns were retrospectively analysed. First, dual feature selection was conducted to identify important feature variables for model construction. Second, ML models were constructed based on the logistic regression (LR), decision tree (DT), support vector machine (SVM) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithms, after which random sampling and tenfold cross-validation were separately used to evaluate and compare these models and identify the optimal model. Finally, we apply the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) interpretable framework to analyse the decision-making principles of the optimal model and expound upon the important factors affecting FI in preterm newborns and their modes of action.

Results

The accuracy of XGBoost was 87.62%, and the area under the curve (AUC) was 92.2%. After the application of tenfold cross-validation, the accuracy was 83.43%, and the AUC was 89.45%, which was significantly better than those of the other models. Analysis of the XGBoost model with the SHAP interpretable framework showed that a history of resuscitation, use of probiotics, milk opening time, interval between two stools and gestational age were the main factors affecting the occurrence of FI in preterm newborns, yielding importance scores of 0.632, 0.407, 0.313, 0.313, and 0.258, respectively. A history of resuscitation, first milk opening time ≥ 24 h and interval between stools ≥ 3 days were risk factors for FI, while the use of probiotics and gestational age ≥ 34 weeks were protective factors against FI in preterm newborns.

Conclusions

In practice, we should improve perinatal care and obstetrics with the aim of reducing the occurrence of hypoxia and preterm delivery. When feeding, early milk opening, the use of probiotics, the stimulation of defecation and other measures should be implemented with the aim of reducing the occurrence of FI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12911-024-02751-5.

Keywords: Preterm newborn, Feeding intolerance, Machine learning, Model construction

Introduction

Preterm newborns are live-born babies whose gestational age is less than 37 weeks [1]. Compared with full-term newborns, preterm newborns exhibit immature gastrointestinal tract development, and gastrointestinal peristalsis develops more slowly than digestion and absorption; thus, preterm newborns are more likely to develop feeding intolerance (FI), which is characterized by vomiting, abdominal distension, gastric retention and other symptoms [2]. Studies have shown that the incidence of FI in preterm newborns in China is 33.80% ~ 53.45% [3], compared with approximately 25% worldwide [4]. FI leads to insufficient nutrient intake and delayed extrauterine growth in preterm newborns [5] and increases the incidence of hospital infection, metabolic disorders, liver damage and other complications [6]. This condition can even increase the financial burden of families and affect their survival rate and quality of life [7, 8]. According to the WHO, approximately 15 million premature babies are born worldwide each year, and approximately 10% to 30% of these babies may die because of FI [9]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to prevent the occurrence of FI.

FI is a common clinical condition with a complex pathogenesis and many influencing factors, so it is difficult to diagnose subjectively. An accurate and effective evaluation tool could help medical staff make early diagnoses and treatment plans. Bozzetti [10] used logistic regression (LR) to predict the FI of newborns with intrauterine growth restriction (IGR). Li Yan et al. [11] used Spearman correlation analysis to explore the relationship between changes in superior mesenteric artery blood flow and FI in preterm newborns before and after feeding. Bozzetti et al. [12] used a generalized linear model to evaluate the relationship between visceral oxygen saturation, superior mesenteric artery Doppler blood flow velocity and FI. In addition, Irles [13] and Lure [14] used artificial neural networks (ANNs) and random forests (RFs) to construct models to predict the risk of neonatal intestinal diseases.

Despite the wealth of information obtained from studies on predicting FI, several shortcomings remain to be addressed. First, models based on traditional statistical methods are easy to operate and do not require substantial human or material resources; however, they often use only a single data mining method, so the resulting model may not be optimal [15, 16]. Second, although a few scholars have introduced machine learning (ML) for model creation, methods for interpreting these results are lacking [17]. Finally, although some biological markers can be used as a basis for the early diagnosis of FI, they are costly and operationally complex and require high human and material resources; moreover, some assessment tools require the use of imaging examinations for prediction, which increases the economic burden for patients and does not meet the public's expectations for a convenient and rapid screening method [18]. Therefore, a systematic, convenient and accurate prediction method is urgently needed to compensate for these shortcomings.

ML enables computers to recognize and acquire knowledge through programming languages and mathematical principles while continuously improving its performance. Compared with traditional statistical methods, ML methods can better acquire hidden information in data and have better learning and generalization abilities [19]. However, ML is limited by the lack of interpretability [20]; on their own, it is impossible to know the mechanisms underlying ML model decisions and whether the results are reliable. For medical diagnosis systems, interpretability is highly important; only by making the model transparent can the decision results be considered more reliable and safer [21]. Based on the above background, this study sought to construct ML models based on the LR, decision tree (DT), support vector machine (SVM) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithms and determine the best risk prediction model. Then, we aimed to introduce the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) interpretable framework, which quantifies and attributes the importance of each feature variable through global and partially interpretable methods and explains the important factors affecting FI in preterm newborns. These findings can provide decision references for clinical workers, thereby facilitating disease management and offering new research ideas for optimizing FI prevention and treatment programs.

Methods

Study design and setting

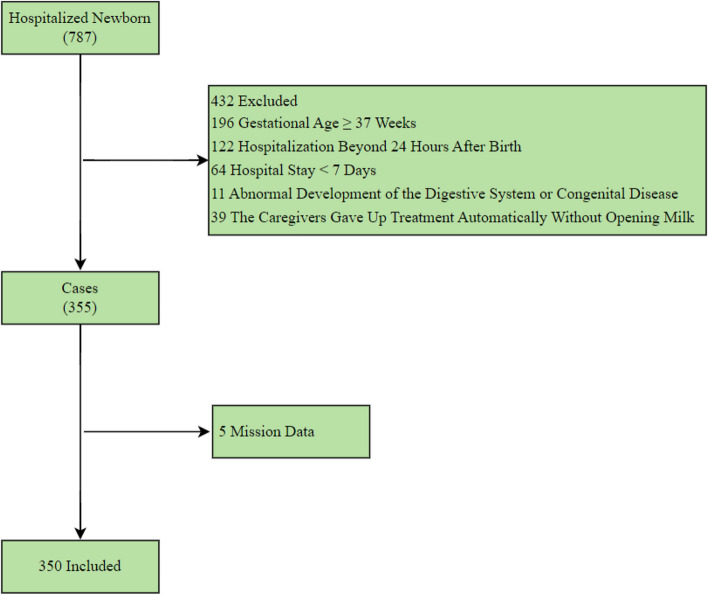

This was a retrospective, single-centre, cross-sectional study. We reviewed a total of 787 patients in the neonatal intensive care unit of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University from January 2021 to February 2022 were analysed. The exclusion criteria were as follows: gestational age ≥ 37 weeks (n = 196), hospitalization beyond 24 h after birth (n = 122), hospital stay < 7 days (n = 64), abnormal development of the digestive system or congenital disease (n = 11) and the caregivers gave up treatment automatically without opening milk (n = 39). According to the exclusion criteria, 432 patients were excluded. In addition, records with more than 70% missing data (n = 5) were also excluded from the analysis, the remaining missing values were imputed with the mean or mode of each variable. Noisy and abnormal values, errors, duplicates, and meaningless data were assessed by researchers in collaboration with two specialists in paediatrics. For different interpretations of the data preprocessing procedure, we contacted the corresponding physicians, the final sample in this study included 350 hospitalized preterm newborns. The detailed exclusions are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart describing patient selection

Of these 350 preterm newborns, including 207 male preterm newborns (59.1%) and 143 female preterm newborns (40.9%), there were 122 newborns (34.9%) with FI and 228 (65.1%) without FI. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relevant variables and their assignments

| Classes | Variables | Assignments | Frequencies | Classes | Variables | Assignments | Frequencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General information of preterm newborns | Sex | 0 = Male | 207(59.1%) | Neonatal diseases | Neonatal asphyxia | 0 = No | 245(70.0%) |

| 1 = Female | 143(40.9%) | 1 = Yes | 105(30.0%) | ||||

| Birth weight | 0 = ≤ 1.5 kg | 43(12.3%) | NRDS | 0 = No | 238(68.0%) | ||

| 1 = < 2.5 kg | 176(50.3%) | 1 = Yes | 112(32.0%) | ||||

| 2 = ≥ 2.5 kg | 131(37.4%) | HIE | 0 = No | 248(70.9%) | |||

| Gestational age | 0 = < 34w | 139(39.7%) | 1 = Yes | 102(29.1%) | |||

| 1 = ≥ 34w | 211(60.3%) | Infection | 0 = No | 68(19.4%) | |||

| Apgar score in one minute | 0 = ≤ 6 points | 81(23.1%) | 1 = Yes | 282(80.6%) | |||

| 1 = ≥ 7 points | 269(76.9%) | Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia | 0 = No | 248(70.9%) | |||

| History of resuscitation | 0 = No | 208(59.4%) | 1 = Yes | 102(29.1%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 142(40.6%) | PDA | 0 = No | 335(95.7%) | |||

| Maternal conditions | Polyembryony | 0 = No | 276(78.9%) | 1 = Yes | 15(4.3%) | ||

| 1 = Yes | 74(21.1%) | Use of medications | PS | 0 = No | 264(75.4%) | ||

| Assisted reproductive | 0 = No | 306(87.4%) | 1 = Yes | 86(24.6%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 44(12.6%) | Probiotics | 0 = No | 117(33.4%) | |||

| Mother's age | 0 = ≤ 24 years | 58(16.6%) | 1 = Yes | 233(66.6%) | |||

| 1 = < 35 years | 229(65.4%) | Antibiotic | 0 = Free | 27(7.7%) | |||

| 2 = ≥ 35 years | 63(18.0%) | 1 = Single | 226(64.6%) | ||||

| Mode of delivery | 0 = Eutocia | 93(26.6%) | 2 = Combined | 97(27.7%) | |||

| 1 = Cesarean | 257(73.4%) | Blood transfusion | 0 = No | 326(93.1%) | |||

| Abnormal fetal position | 0 = No | 304(86.9%) | 1 = Yes | 24(6.9%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 46(13.1%) | Others | Apnea | 0 = No | 262(74.9%) | ||

| Amniotic fluid abnormality | 0 = No | 238(68.0%) | 1 = Yes | 88(25.1%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 112(32.0%) | High temperature | 0 = No | 248(70.9%) | |||

| Umbilical cord abnormality | 0 = No | 231(66.0%) | 1 = Yes | 102(29.1%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 119(34.0%) | Interval between two stools | 0 = < 3 days | 263(75.1%) | |||

| Placenta abnormality | 0 = No | 270(77.1%) | 1 = ≥ 3 days | 87(24.9%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 80(22.9%) | Milk opening time | 0 = < 24 h | 226(64.6%) | |||

| Premature rupture of membranes | 0 = No | 223(63.7%) | 1 = ≥ 24 h | 124(35.4%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 127(36.3%) | Mechanical ventilation | 0 = No | 246(70.3%) | |||

| Pregnancy complications | 0 = No | 148(42.3%) | 1 = Yes | 104(29.7%) | |||

| 1 = Yes | 202(57.7%) | Outcome variable | Occurrence of FI | 0 = No | 228(65.1%) | ||

| 1 = Yes | 122(34.9%) |

NRDS neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, HIE hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, PDA patent ductus arteriosus, PS pulmonary surfactant; FI feeding intolerance

Relevant variables

This study collected relevant risk factors for FI in preterm newborns after consulting the literature and consultation experts. In the database, a total of 30 variables were obtained for each patient, including general preterm newborn information (5 variables), maternal conditions (10 variables), neonatal diseases (6 variables), the use of medications (4 variables), and other variables (5 variables). The occurrence of FI was considered the outcome variable, and the presence of one or more of the following symptoms within two weeks of birth was defined as FI [22, 23]: ① multiple episodes of postfeeding vomiting with a frequency of ≥ 3 times/day; ② abdominal distention (abdominal circumference increased > 1.5 cm within 24 h); ③ gastric residual > 50% of the previous feeding; ④ frequency of feeding schedule interruption (fasting) > 2 times/day; and ⑤ dark liquid in the stomach. These variables and their assignments are shown in Table 1.

Database splitting

In this study, 70% (245 samples) of the 350 samples were randomly selected as the training set, while the remaining 30% (105 samples) were selected as the test set. We used the training set for feature selection and model training, to ensure the full learning of the models, a grid search was used for parameter tuning (with optimal accuracy as the selection criterion), and the Youden rule was used to calculate the Youden index to derive the optimal classification threshold of the model; secondly, we use the same training set for tenfold cross-validation; finally, the test set was used to evaluate the model.

Dual feature selection

The purpose of dual feature selection [24] is to identify informative features from high-dimensional data by removing redundant and irrelevant features to improve classification accuracy. Spearman correlation [25] indicates the direction and strength of the correlation between two variables by calculating the correlation coefficient. RF [26] obtains the importance score and ranking of each feature by calculating the average contribution of each feature to multiple decision trees that construct the corresponding model so that the more important features can be selected.

Spearman correlation analysis was first used to determine the feature variables that were significantly correlated with FI in preterm newborns. We determined the strength of the relationship by calculating the correlation coefficient, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The feature importance ranking of each factor was subsequently obtained via RF, and those factors with an importance greater than 5 were selected for inclusion in the model.

Model development and cross-validation

We used various ML methods to develop four models for predicting FI: LR, DT, SVM, and XGBoost. LR [20] uses the maximum likelihood to determine the regression coefficient for predicting the probability that the dependent variable belongs to a certain category.

DT [21] summarizes and classifies a data sample and finds an exact description and classification model for the attributes exhibited. SVM [27] classifies data samples according to the decision surface with the largest geometric interval; this approach is suitable for classifying a small amount of high-dimensional data and has good effectiveness and generalizability. XGBoost [28, 29] is a boosting tree model that forms a strong classifier by integrating multiple classification and regression trees (CARTs) together. It has demonstrated high accuracy and a fast running speed in certain scenarios, can effectively reduce overfitting using regularization techniques, and has good tolerance for outliers and missing values.

To reduce the impact of data division on the prediction results and to verify the generalization ability of the models, the tenfold cross-validation [30] method was employed. The dataset was divided into 10 parts; for each fold, 9 of the parts were selected as the training set, and the remaining one was used as the test set. These data are subsequently used for model training and evaluation. Unlike in the random sampling method, in the tenfold cross-validation method, the average of the 10 Youden indices is taken as the optimal classification threshold of the model, and the average of the 10 prediction outcomes is taken as the evaluation index.

Indicators for model evaluation

The accuracy (Acc), sensitivity (Sen), specificity (Spe), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and area under the curve (AUC) on the test set were selected as indicators for model evaluation. Furthermore, the model with the best performance was selected for identification of the risk factors most related to FI, as interpreted by the SHAP method.

SHAP interpretable framework

The SHAP interpretable framework is a method for resolving the "black box" nature of the model. SHAP provides an estimate of the contribution of each feature, that is SHAP value, and the final prediction results of the model can be obtained by adding the contribution value of each feature [31]. Compared with traditional feature importance methods, the SHAP interpretable framework can reveal the positive and negative relationships of each predictive factor relative to the target variable and can be used for global and partial interpretation [32]. In this study, the SHAP interpretable framework was introduced to analyse the risk factors for FI in preterm newborns by global and partially interpretable methods.

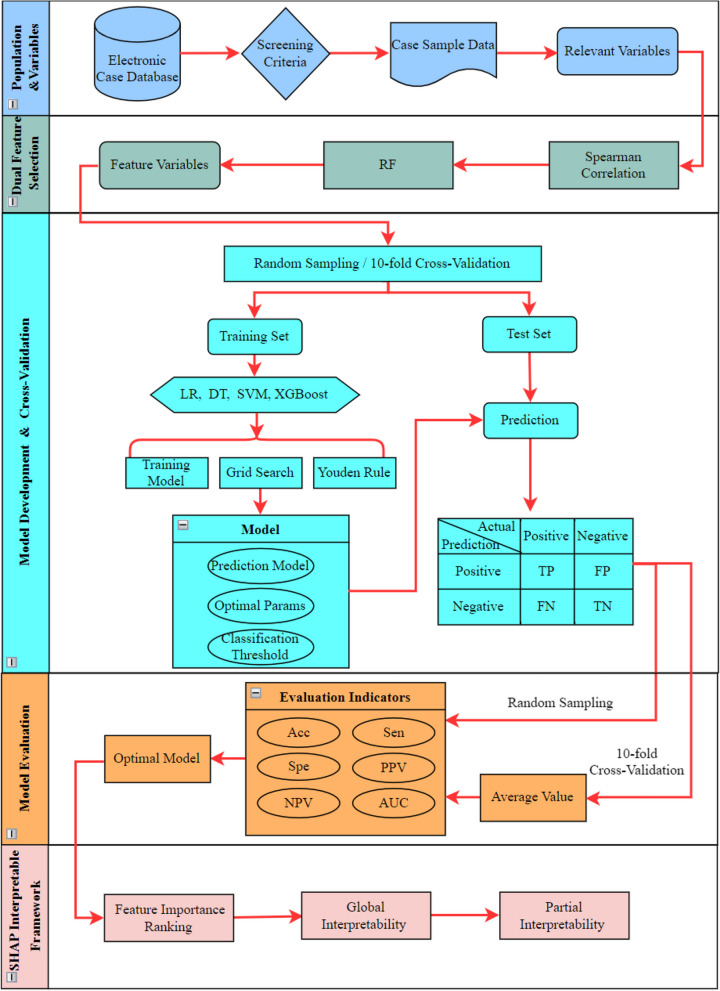

The overall process is shown in Fig. 2. All the statistical analyses, ML algorithm, and SHAP methods were conducted in R (version 4.2.0; Austria), an open-source, freely available, integrated software environment for data manipulation, computation, analysis, and graphical display [33].

Fig. 2.

Modeling process of risk prediction model for FI of preterm newborns. Notes: RF, random forest; LR, logistic regression; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine; XGBoost, eXtreme Gradient Boosting; TP, true positive; FP, false positive; FN, false negative; TN, true negative; Acc, accuracy; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value

Results

Spearman correlation analysis

A total of 16 factors were significantly related to FI in preterm newborns; of these factors, gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score in one minute, and probiotics were negatively correlated with FI in preterm newborns, while neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (NRDS), neonatal asphyxia, infection, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), apnoea, high temperature, mechanical ventilation, history of resuscitation, milk opening time, interval between two stools, blood transfusion, and pulmonary surfactant (PS) were positively correlated with FI in preterm newborns. The data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation analysis of FI in preterm newborns

| Risk factors | Correlation coefficient | Risk factors | Correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | -0.071 | HIE | -0.021 |

| Gestational age | -0.472** | Neonatal asphyxia | 0.280** |

| Birth weight | -0.513** | Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia | 0.032 |

| Apgar score in one minute | -0.295** | Infection | 0.147** |

| Mother's age | -0.008 | PDA | 0.171** |

| Polyembryony | 0.018 | Apnea | 0.309** |

| Assisted reproductive | -0.024 | High temperature | 0.309** |

| Pregnancy complications | -0.005 | Mechanical ventilation | 0.417** |

| Mode of delivery | -0.089 | History of resuscitation | 0.556** |

| Abnormal fetal position | 0.088 | Milk opening time | 0.398** |

| Amniotic fluid abnormality | -0.013 | Interval between two stools | 0.481** |

| Umbilical cord abnormality | 0.032 | Blood transfusion | 0.323** |

| Placenta abnormality | 0.016 | Antibiotic | 0.105 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 0.034 | PS | 0.321** |

| NRDS | 0.359** | Probiotics | -0.371** |

FI feeding intolerance, NRDS neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, HIE hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, PDA patent ductus arteriosus, PS pulmonary surfactant

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Model development, cross‑validation and model evaluation

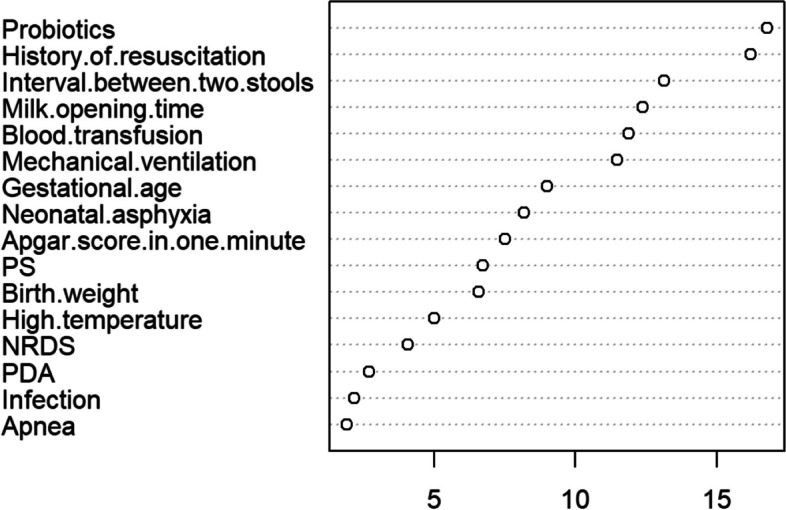

RF was used to further select the features from among the 16 factors above, yielding the feature importance rankings, as shown in Fig. 3. Finally, 12 features with an importance value greater than 5 were selected for inclusion in the model; these included probiotics, history of resuscitation, interval between two stools, milk opening time, blood transfusion, mechanical ventilation, gestational age, neonatal asphyxia, Apgar score in one minute, PS, birth weight, and high temperature.

Fig. 3.

Feature importance ranking of RF. Notes: PS, Pulmonary surfactant; NRDS, Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome; PDA, Patent ductus arteriosus

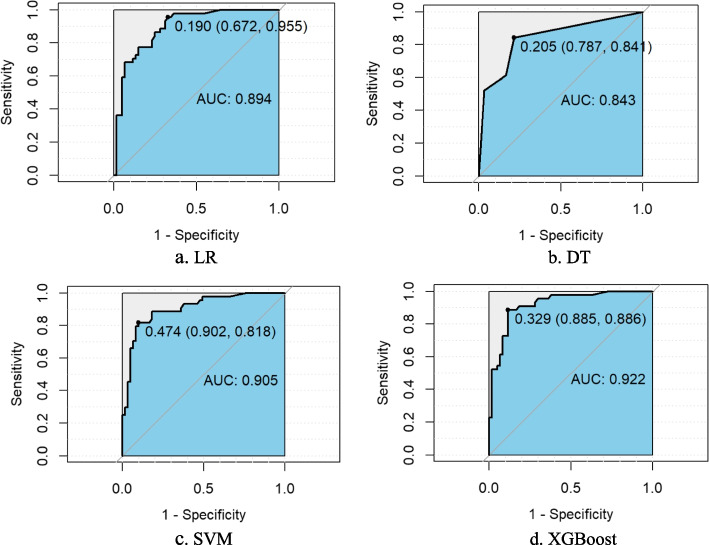

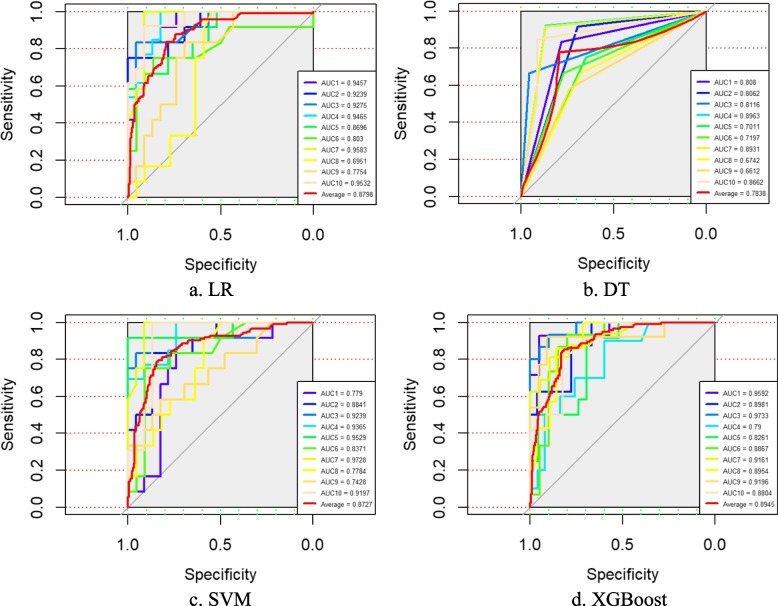

Four classification prediction models built from the LR, DT, SVM and XGBoost algorithms were constructed using the 12 feature variables obtained after dual feature selection as dependent variables and the occurrence of FI as the predictor variable. These models were subsequently validated in the original dataset separately via random sampling and tenfold cross-validation methods, and the Acc, Sen, Spe, PPV, NPV and AUC values of each model were obtained on the test set, as shown in Table 3. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the two verification methods are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. A comparison of the data revealed that XGBoost yielded the optimal evaluation indices under both validation methods.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix and AUC values of each model on the test set

| Random sampling | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 80.95 | 75.00 | 85.25 | 78.57 | 82.54 | 89.40 |

| DT | 74.29 | 61.36 | 83.61 | 72.97 | 75.00 | 84.30 |

| SVM | 85.71 | 81.82 | 88.52 | 83.72 | 87.10 | 90.50 |

| XGBoost | 87.62 | 86.36 | 88.52 | 84.44 | 90.00 | 92.20 |

| tenfold cross-validation | ||||||

| LR | 79.61 | 78.53 | 80.24 | 68.38 | 87.98 | 87.98 |

| DT | 78.75 | 77.69 | 79.33 | 68.15 | 87.10 | 78.38 |

| SVM | 76.13 | 70.83 | 78.95 | 69.42 | 81.51 | 87.27 |

| XGBoost | 83.43 | 82.83 | 83.83 | 72.12 | 90.51 | 89.45 |

AUC area under the curve, Acc accuracy, Sen sensitivity, Spe specificity, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, LR logistic regression, DT decision tree, SVM support vector machine, XGBoost eXtreme Gradient Boosting

Fig. 4.

The ROC curves of each model obtained by random sampling method on the test set. Notes: LR, logistic regression; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine; XGBoost, eXtreme Gradient Boosting

Fig. 5.

The ROC curves of each model obtained by tenfold cross-validation on the test set. Notes: LR, logistic regression; DT, decision tree; SVM, support vector machine; XGBoost, eXtreme Gradient Boosting

SHAP interpretable framework

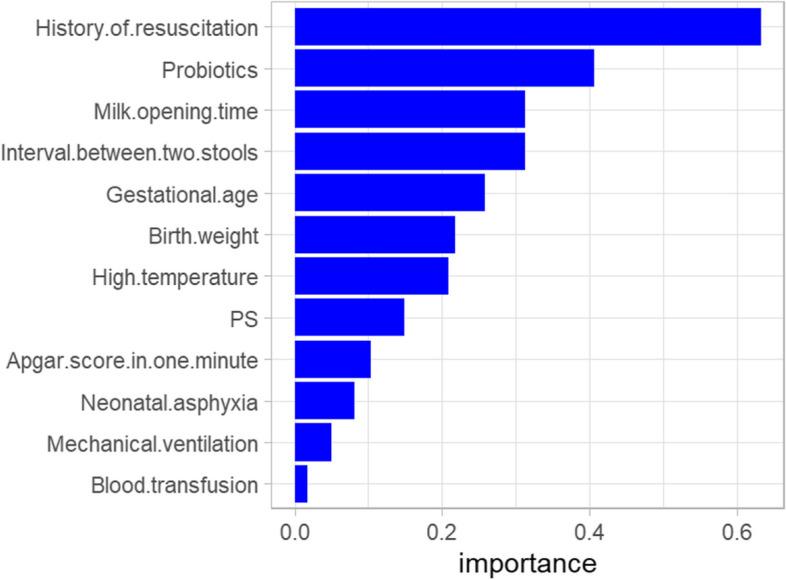

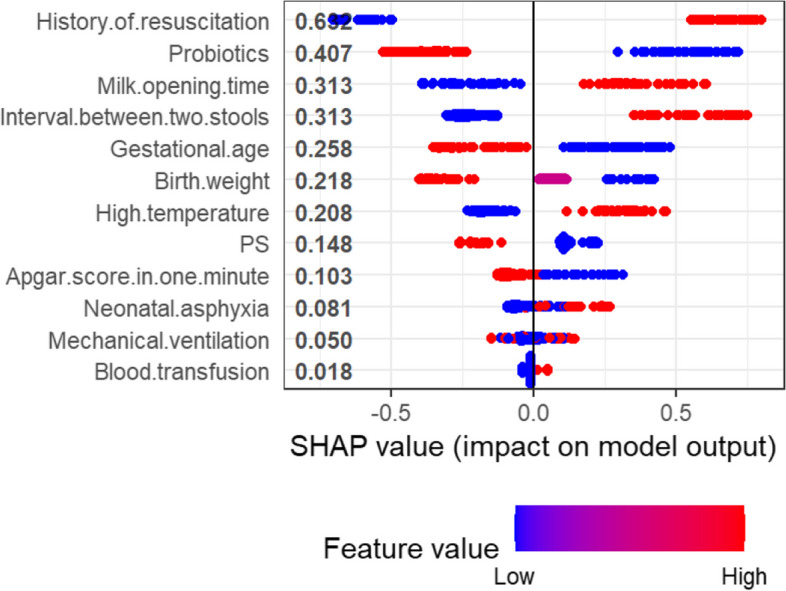

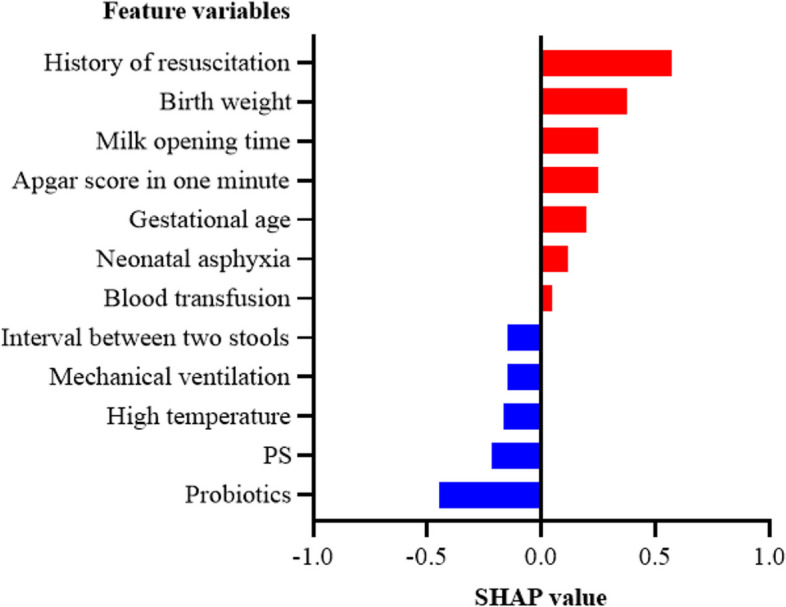

Feature importance ranking with the SHAP interpretable framework

The importance of each feature was ranked according to the absolute SHAP value. The five most common features were history of resuscitation, probiotics, milk opening time, interval between two stools and gestational age (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Feature importance ranking of SHAP interpretable framework. Notes: PS, Pulmonary surfactant

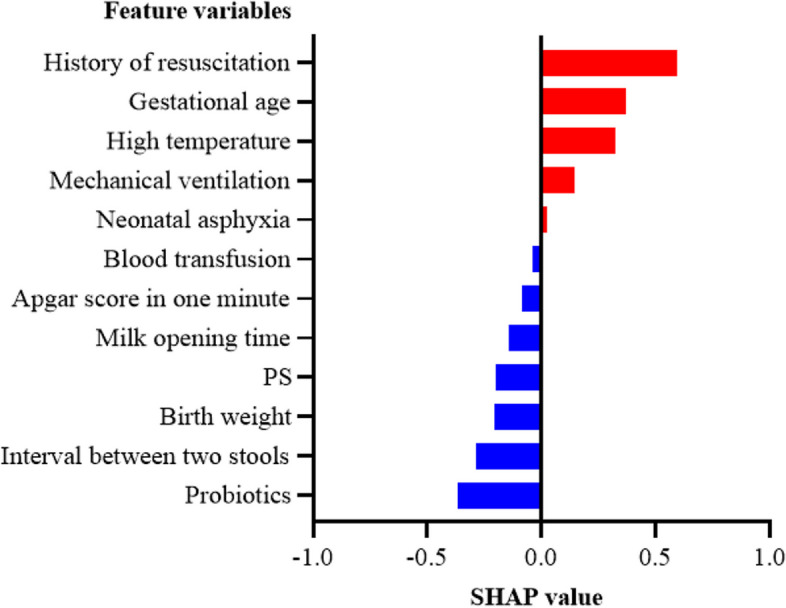

Global interpretability with the SHAP interpretable framework

To clarify the effect of these feature variables on the occurrence of FI in preterm newborns, the SHAP feature summary of the XGBoost model was further derived, as shown in Fig. 7. The vertical coordinates in the figure are the feature variables in order of importance, the colours from blue to red indicate that the feature values change from low to high, and the horizontal coordinates are the SHAP values. A positive SHAP value indicates that the feature value has a positive effect on FI; otherwise, it has a negative effect. The use of probiotics, increased gestational age and increased birth weight reduce the probability of FI in preterm newborns, while a history of resuscitation, late milk opening time, and a long interval between two stools increase the probability of FI in preterm newborns.

Fig. 7.

SHAP feature summary of the XGBoost. Notes: PS, Pulmonary surfactant

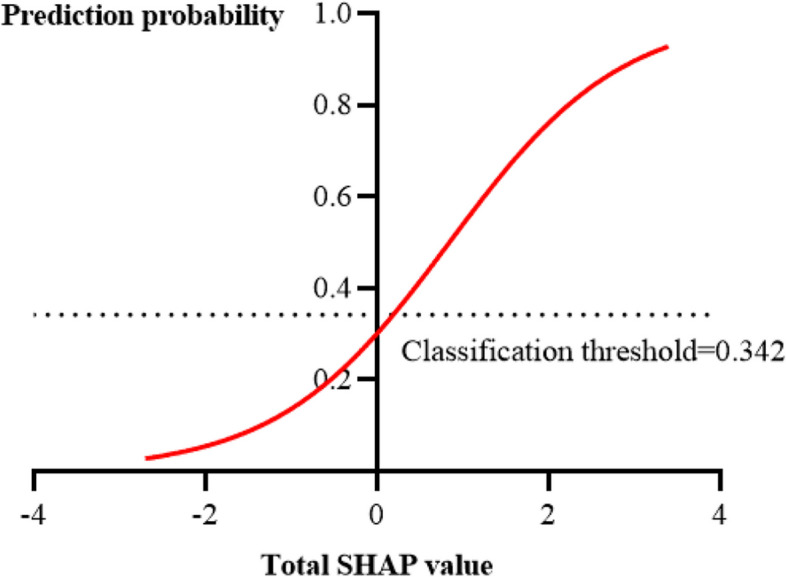

Partial interpretability with the SHAP interpretable framework

This study used the Youden rule to obtain the optimal classification threshold. According to the feature input of each case sample, the model outputs the predicted probability of FI; if the predicted probability is greater than the classification threshold, the patient is expected to develop FI; otherwise, they are expected to have feeding tolerance (FT). The classification threshold for the XGBoost model was 0.342 in this study. By comparing the total SHAP value and the prediction probability of each sample, a positive correlation was identified, as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Relationship between total SHAP value and prediction probability

To illustrate the relationships among the SHAP value, prediction probability and prediction classification of samples with the XGBoost model, two samples yielding accurate predictions but different results were selected for analysis.

Figure 9 shows a sample predicted to be FI, with a total SHAP value of 0.685 and a predicted probability of 0.461, which is greater than the classification threshold and therefore accurately judged to be FI. This patient had been treated with probiotics and had a normal temperature, normal stool time, etc.; each of these features had a negative SHAP value, indicating that these conditions would reduce the probability of FI. The patient also had a history of resuscitation, low birth weight, young gestational age, etc.; all of these features had positive SHAP values, indicating that these conditions increase the probability of FI. The sample was ultimately predicted to have FI, indicating that the latter group of features had a greater impact on the development of the condition in these patients.

Fig. 9.

Partial interpretability of FI in preterm newborns

Figure 10 shows that a patient was predicted to have FT with a total SHAP value of 0.129 and a predicted probability of 0.329, which is less than the classification threshold; therefore, the patient was correctly judged to have FT. Compared to the patient in Fig. 9, high birth weight, a normal stool interval and the use of probiotics dominated the predictions for this patient, resulting in a correct prediction of FT.

Fig. 10.

Partial interpretability of FT in preterm newborns

A comparison of the two samples revealed that the occurrence of FI was the result of the combined effect of the above 12 features, and different values of the same feature may have opposite effects. This finding also showed that the pathogenesis of FI is complex and involves many influencing factors, which makes diagnosis difficult; however, a model based on XGBoost can accurately identify and predict FI.

Discussion

This study proposes for the first time the construction and SHAP interpretability analysis of a risk prediction model for FI in preterm newborns based on ML, which fills the gap in the prediction of FI in preterm newborns by ML. At the same time, these findings can provide decision references for clinical workers, thereby facilitating disease management and offering new research ideas for optimizing FI prevention and treatment programs. We found that the XGBoost algorithm was significantly superior to the other classifiers, and SHAP interpretability analysis revealed that a history of resuscitation, use of probiotics, milk opening time, interval between two stools and gestational age were the main factors affecting the occurrence of FI.

We found that preterm newborns with a history of resuscitation, late opening of milk, or longer intervals between stools were more likely to develop FI. First, a history of resuscitation is usually accompanied by hypoxia, which can cause multiple-organ dysfunction. To ensure blood flow to vital organs such as the brain and heart, blood flow to organs such as the stomach and muscles is reduced, leading to a disturbance in energy metabolism in intestinal epithelial cells and damage to the mucosal barrier. In addition, many free radicals are produced during hypoxia-reperfusion, which can cause gastrointestinal mucosal damage. It has been reported [34] that the incidence of FI in preterm newborns with hypoxia reaches 35.37%. Second, early feeding can promote gastric electrophysiological activity and gastrointestinal maturation as well as the activation and release of gastrointestinal hormones, improve the digestive function and gastrointestinal structure of preterm newborns, and prevent the occurrence of FI to a certain extent. Finally, normal newborns defecate for the first time within 12 h after birth. Longer intervals between stools may be related to gastrointestinal tract injury in preterm newborns.

In contrast, preterm newborns who have been treated with probiotics and are older are less likely to develop FI for several reasons: First, probiotics have the potential to improve intestinal maturity and function in many ways and have been shown to reduce the risk of FI [35]. A previous study [36] also showed that probiotics have a protective effect on the intestine of very-low-birth-weight newborns. Second, functional peristalsis of the small intestine first emerges at approximately 30 weeks of gestation, and regular compound movement emerges at 33 ~ 34 weeks of gestation. Gastrin, motilin and other gastrin-intestinal peptide hormones in the foetus reach normal secretion levels at term [37]. Several studies [38] have shown that the incidence of FI in foetuses ≤ 32 weeks old is 41.18%, whereas that in foetuses > 32 weeks old is 22.38%, indicating that the incidence of FI increases with decreasing gestational age. In addition, Boo et al. [39] showed that the only significant risk factor associated with FI was the time of first feeding; the earlier the first feeding time was, the lower the risk of FI. Other factors, such as birth weight, history of resuscitation, perinatal asphyxia, Apgar score in one minute, mechanical ventilation, use of PS, NRDS, PDA, mode of delivery and sex, were not associated with FI.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-centre, cross-sectional study in which the temporal sequence of exposure factors and disease was often difficult to assess. Second, the sample size was small, and additional data are needed to optimize and validate the learning and generalizability of the model. Finally, the parameters of the ML algorithms were adjusted only to select the optimal model but not to optimize the algorithm itself.

Conclusions

The integrated classifier based on XGBoost showed significantly superior accuracy and reliability compared to other single classifiers. A history of resuscitation, a first milk opening time ≥ 24 h after birth and an interval between defecations ≥ 3 days were risk factors for FI, while the use of probiotics and a gestational age ≥ 34 weeks were protective factors against FI in preterm newborns. These findings can provide decision references for clinical workers and offer new research ideas for optimizing FI prevention and treatment programs. However, the results of this study need to be further verified through additional studies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank mothers and their neonates who participated in the study.

Abbreviations

- Acc

Accuracy

- ANNs

Artificial neural networks

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CARTs

Classification and regression trees

- DT

Decision tree

- FI

Feeding intolerance

- FT

Feeding tolerance

- FN

False negative

- FP

False positive

- HIE

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- IGR

Intrauterine growth restriction

- LR

Logistic regression

- ML

Machine learning

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- NRDS

Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- PS

Pulmonary surfactant

- RF

Random forest

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SHAP

SHapley additive explanation

- SVM

Support vector machine

- Sen

Sensitivity

- Spe

Specificity

- TP

True positive

- TN

True negative

- XGBoost

EXtreme gradient boosting

Authors’ contributions

Hui Xu carried out the data collection, conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to the analysis plan, interpreted the results and drafted the initial manuscript. Xingwang Peng drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript. Ziyu Peng and Rui Wang analyzed data, created tables and figures, and drafted the initial manuscript. Lianguo Fu and Rui Zhou provided input on the design and implementation of the analysis, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding

This work was supported by the 512 Talent Cultivation Plan of Bengbu Medical College (by51201204) and the overseas visiting and training programs for outstanding young core talents in universities (gxgwfx2020042). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Bengbu Medical College ([2018] No. 015). The Medical Ethics Committee of the Bengbu Medical College waived the requirement for informed consent because of the retrospective nature of this study and because all data including personal basic information and detailed medical records were encrypted. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lianguo Fu and Rui Zhou contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Rui Zhou, Email: 1176034941@qq.com.

Lianguo Fu, Email: lianguofu@bbmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Walani SR. Global burden of preterm birth[J]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):31–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seiiedi-Biarag L, Mirghafourvand M. The effect of massage on feeding intolerance in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis study[J]. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minmin L, Zaixia S, Jin L, et al. Evidence summary for prevention and management of feeding intolerance in preterm infants[J]. Chin J Nurs. 2020;55(08):1163–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegar B. Gastroesophageal reflux in infants[J]. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45(Suppl 1):69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan Z, Yan J, Wen H, et al. Feeding intolerance alters the gut microbiota of preterm infants[J]. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1): e0210609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosmeri C, Giapros V, Rallis D, et al. Classification and special nutritional needs of SGA infants and neonates of multiple pregnancies[J]. Nutrients. 2023;15(12):2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Çaka S Y, Topal S, Yurttutan S, et al. Effects of kangaroo mother care on feeding intolerance in preterm infants[J]. J Trop Pediatr. 2023,69(2):fmad015. 10.1093/tropej/fmad015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Swanson JR, Becker A, Fox J, et al. Implementing an exclusive human milk diet for preterm infants: real-world experience in diverse NICUs[J]. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith J. The impact of early-life stress on cognitive development[J]. Journal of Child Psychology. 2019;45(2):123–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozzetti V, Paterlini G, Gazzolo D, et al. Monitoring Doppler patterns and clinical parameters may predict feeding tolerance in intrauterine growth-restricted infants[J]. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(11):e519–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan L, Min F, Jizhang L, et al. Relationship between changes of blood flow velocity of superior mesenteric artery before and after the feeding with color Doppler ultrasonography and tolerance to enteral feeding in premature neonates[J]. Chin J Med Imag Technol. 2007;01:102–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bozzetti V, Paterlini G, Meroni V, et al. Evaluation of splanchnic oximetry, Doppler flow velocimetry in the superior mesenteric artery and feeding tolerance in very low birth weight IUGR and non-IUGR infants receiving bolus versus continuous enteral nutrition[J]. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irles C, González-Pérez G, Carrera MS, et al. Estimation of neonatal intestinal perforation associated with necrotizing enterocolitis by machine learning reveals new key factors[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lure AC, Du X, Black EW, et al. Using machine learning analysis to assist in differentiating between necrotizing enterocolitis and spontaneous intestinal perforation: A novel predictive analytic tool[J]. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(10):1703–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afrash MR, Shafiee M, Kazemi-Arpanahi H. Establishing machine learning models to predict the early risk of gastric cancer based on lifestyle factors[J]. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afrash MR, Mirbagheri E, Mashoufi M, et al. Optimizing prognostic factors of five-year survival in gastric cancer patients using feature selection techniques with machine learning algorithms: a comparative study[J]. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H, Lee EH, Lee KS, et al. Machine learning-based risk factor analysis of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants[J]. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):21407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dani C, Corsini I, Generoso M, et al. Splanchnic Tissue Oxygenation for Predicting Feeding Tolerance in Preterm Infants[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39(8):935–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerner J, Dogan A, von Recum H. Machine learning and big data provide crucial insight for future biomaterials discovery and research[J]. Acta Biomater. 2021;130:54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petch J, Di S, Nelson W. Opening the Black Box: The Promise and Limitations of Explainable Machine Learning in Cardiology[J]. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38(2):204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Liu S, Hu Y, et al. Predicting Mortality in Intensive Care Unit Patients With Heart Failure Using an Interpretable Machine Learning Model: Retrospective Cohort Study[J]. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(8): e38082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang H, Wenxing L, Jun T, et al. Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm infants(2020). [J]. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2020;22(10):1047–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fanaro S. Feeding intolerance in the preterm infant[J]. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(Suppl 2):S13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Wang Y, Ruiz R. A Survey on Sparse Learning Models for Feature Selection[J]. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;52(3):1642–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elboim-Gabyzon M, Pitluk M, Shuper EE. The correlation between physical and emotional stabilities: a cross-sectional observational preliminary study[J]. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1678–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gündoğdu S. Efficient prediction of early-stage diabetes using XGBoost classifier with random forest feature selection technique[J]. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023:1–19. 10.1007/s11042-023-15165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hu M, Zou L, Lu J, et al. Construction of a 5-feature gene model by support vector machine for classifying osteoporosis samples[J]. Bioengineered. 2021;12(1):6821–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paleczek A, Grochala D, Rydosz A. Artificial breath classification using XGBoost algorithm for diabetes detection[J]. Sensors (Basel). 2021;21(12):4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou N, Li M, He L, et al. Predicting 30-days mortality for MIMIC-III patients with sepsis-3: a machine learning approach using XGboost[J]. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaliappan J, Bagepalli AR, Almal S, et al. Impact of cross-validation on machine learning models for early detection of intrauterine fetal demise[J]. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(10):1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsa AB, Movahedi A, Taghipour H, et al. Toward safer highways, application of XGBoost and SHAP for real-time accident detection and feature analysis[J]. Accid Anal Prev. 2020;136: 105405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wojtuch A, Jankowski R, Podlewska S. How can SHAP values help to shape metabolic stability of chemical compounds?[J]. J Cheminform. 2021;13(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan B. Data Analysis Using R Programming[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1082:47–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang L. Clinical Analysis for the Feeding Intolerance in 56 cases of Preterm Neonates[J]. The Journal of Medical Theory and Practice. 2004;07:765–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deshmukh M, Patole S. Current Status of Probiotics for Preterm Infants[J]. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88(7):703–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Totsu S, Yamasaki C, Terahara M, et al. Bifidobacterium and enteral feeding in preterm infants: cluster-randomized trial[J]. Pediatr Int. 2014;56(5):714–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenfestey MW, Neu J. Gastrointestinal Development: Implications for Management of Preterm and Term Infants[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47(4):773–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menghua W, Yannan Z, Zheng Z. Factors affecting feeding intolerance in preterm infants of different gestational ages[J]. J Univ S China(Medical Edition). 2017;45(02):160–4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boo NY, Soon CC, Lye MS. Risk factors associated with feed intolerance in very low birthweight infants following initiation of enteral feeds during the first 72 hours of life[J]. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46(5):272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.