The stigma surrounding mental illness and suicide is prevalent worldwide, inhibiting people from seeking help and limiting their access to available mental health facilities. Consequently, it widens the gap in the treatment of mental health. 1 There have been innumerable anti-stigma initiatives by lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) that have replicated the already existing strategies used by high-income countries (HICs), hoping for a similar outcome. The current article highlights the necessity for launching an antistigma campaign tailored to our demographics, with a strong focus on using an emic approach as its foundation. 1

Treatment of mental illnesses is a significant global public health issue as it is considered to be an integral and necessary component of holistic health. Neuropsychiatric disorders constitute approximately 10.8% of the total cases of mental illness in India on a global scale. 2 Additionally, findings from the National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) conducted from 2015 to 2016 underscored a substantial treatment gap for mental health in India, reaching as high as 83.4%.3,4 In the realm of mental health care service and resource utilization, various factors contribute to the treatment gap, encompassing a lack of perceived necessity, societal stigma, insufficient awareness regarding the accessibility and availability of healthcare resources, a desire for personal agency in addressing mental health concerns, financial constraints hindering treatment affordability, and uncertainty regarding treatment efficacy. 5

Among these factors, stigma and discrimination against individuals with mental and behavioral disorders emerge as the foremost barrier, necessitating community attention. 5 Recent studies have elucidated the detrimental impact of mental illness stigmatization manifesting in diminished self-esteem, poor quality of life, negative perceptions toward mental health services, lack of social support, and unfavorable prognoses for affected individuals.6,7 The “Mental Health Santhe-Wellness is Fundamental” campaign by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru (NIMHANS), India, is a standout initiative that integrates a cultural framework into mental health interventions to combat stigma and promote social integration. By prioritizing cultural sensitivity, the campaign engaged diverse communities and incorporated local perspectives into its design and implementation. Embracing cultural diversity and fostering partnerships with grassroot organizations, community leaders, policymakers, mental health professionals, and affected individuals, the campaign increased its relevance and effectiveness across different cultural contexts. This approach promoted a more inclusive and equitable mental health care program aimed at raising awareness. 8

Anti-stigma campaigns in HICs such as Time to Change in England, Beyond Blue in Australia, Like Minds Like Mine in New Zealand, Opening Minds in Canada, and Beyond the Label in Singapore have made significant strides in stigma reduction over the past two decades. These campaigns have achieved success by aligning with their respective cultural values. 9

Similarly, every country must undertake comprehensive initiatives, regardless of challenges such as cost, complexity, and cultural disparities, when designing and implementing interventions. In order to achieve this, many LMICs have started anti-stigma campaigns to overcome cultural barriers.9,10 Global interventions often neglect the unique perspectives and healing practices of collective societies in LMICs. 10 In countries like India, physical community engagement is crucial due to societal reliance on interpersonal interactions. The “Mental Health Santhe-Wellness is Fundamental” campaign by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India, stands out as an innovative initiative. The term “Santhe,” derived from Kannada and translated to “market,” carries cultural connotations beyond its literal meaning. It embodies the notion of a communal gathering held periodically where people come together to sell, buy, and engage in various other activities, fostering a sense of unity and belonging. Traditional Indian marketplaces known by various regional names like “Santhe,” “Sandhai,” “Mandi,” “Sandhi,” “Vipani,” and “Haat,” have deep roots in the country’s socio-cultural fabric, serving as hubs for trade and social interactions. Over time, these gatherings have evolved into modern-day festivals and events such as “Chitra Santhe” for art (showcasing drawings and paintings like a market), “Margazhi Maha Utsavam” (celebration of classical music and art forms), and “Basavangudi Kadalekai Parishe” (an annual groundnut fair), showcasing the transformation of the indigenous concept into diverse markets for music, art, services, and exhibitions.

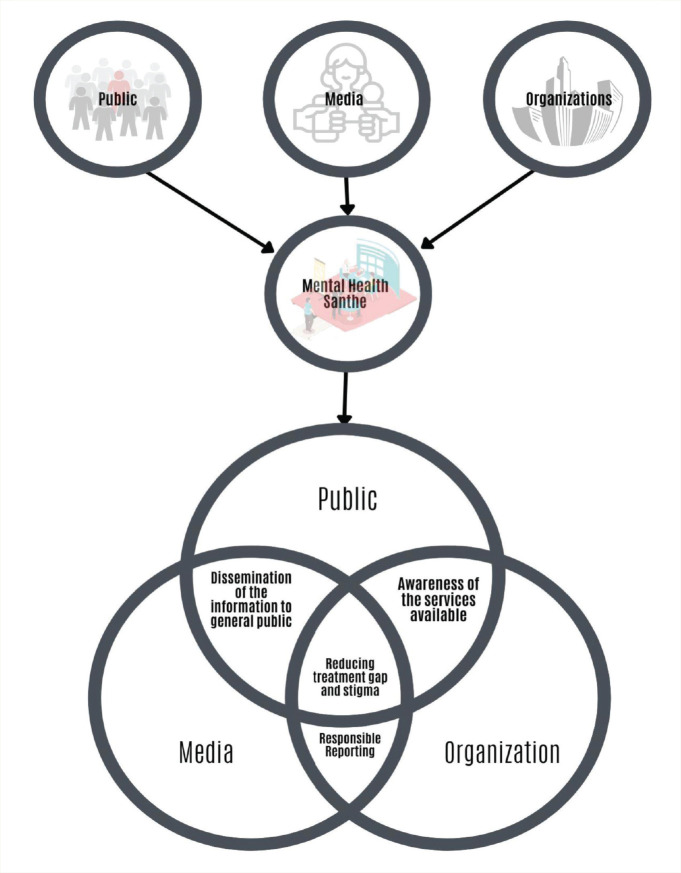

In a similar vein, the Mental Health Santhe brought together a diverse array of key stakeholders, bringing their expertise in areas of mental health and suicide prevention to promote mental well-being through community engagement. What sets it apart from other mental health campaigns globally is builing upon the pre-existing concept of “Santhe,” emphasizing cultural relevance, community engagement, and multidisciplinary collaboration of the public, media, and organizations for initiating conversations around mental health (Figure 1). Held on November 3, 2022, at the Convention Center, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, the event featured approximately 50 stalls representing various organizations and departments of the institute, showcasing their efforts, services, and products within the broader scope of mental health and suicide prevention. These stakeholders encompassed participating organizations from the Southern Indian States, including NGOs, INGOs, hospitals, and counseling centers, alongside media representatives and the general public. Recognizing the critical role of public awareness in combating stigma and addressing the treatment gap, the event aimed to provide a unified platform for all-encompassing media, mental health organizations, community stakeholders, the public, etc., to learn about affordable service availability, interdisciplinary treatment approaches, responsible media reporting, and accessibility to credible mental health resources. The organizing team visited hospitals, cafeterias, educational institutions, and other public places as part of their outreach activities to raise awareness of the event.

Figure 1. Interactions of Three Stakeholders Before and After Mental Health Santhe.

Additionally, an active social media campaign was implemented to enhance awareness, comprising daily posts in both English and Kannada across platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Before the event, a press conference was convened to garner publicity and emphasize the importance of such initiatives for the general public through national and regional media channels, including print, audiovisual, and digital platforms. Engaging with approximately 15 national and regional media outlets enhanced the coverage of the Mental Health Santhe, extending from pre-event promotion to post-event reflections, across various digital platforms. To raise awareness about mental health and suicide prevention, the interdisciplinary departments of the institute showcased information about the range of services accessible to the public. The services included training on media and mental health education, immediate care for psychological emergencies, gatekeeper training for suicide prevention, and psychosocial support for disaster management. In addition, services for women’s mental health, child and adolescent mental health, de-addiction services, digital detox, technology addiction, rehabilitation, telemedicine, mobile mental health applications, and assistance for the elderly with dementia were displayed. Services related to Yoga and Ayurveda were offered by Department of Integrative Medicine, NIMHANS.

Additionally, film-based interventions were screened in the regional language to improve public understanding of mental health and reduce stigma. Three films were included: “Turbulence,” a short film about handling work-related stress; “Understanding Brain through Puppetry,” which explores brain awareness using the Japanese puppetry style “Bunraku”; and “Kaalaji” and “Antara,” two films emphasizing the value of sensitivity toward the elderly. The nursing students also performed mime and street plays on the themes of “Suicide Prevention,” “Mobile Addiction,” and “Alcohol and Addiction.”

Several participating organizations provide a range of essential services, including halfway homes, palliative care, suicide prevention helplines, suicide gatekeeper courses, family support groups, rehabilitation services, vocational training programs, LGBTQ+ well-being services, and more. More than two thousand people from every walk of life visited the event, engaging with stakeholders to explore the breadth of available services and gain insights into how to access them conveniently. Interactive activities such as a quiz on mental health, a photo booth, and games were organized at the stalls to engage the public. They were also offered informative flyers, badges, bookmarks, and brochures as takeaways. The “hope wall” was one of the key attractions aimed at sensitizing people about suicide prevention, where visitors wrote their feelings, emotions, and motivational quotes and pasted them on the wall, in keeping with the theme of stigma reduction, a Recovery Oriented Services (ROSes) café run by persons with mental illness, under the supervision of an instructor put up a food stall to facilitate direct interaction with the public. It helped improve the public perception regarding the behavior and capabilities of people with mental illnesses, with appropriate support and accommodations.

This unique anti-stigma program was designed to raise awareness of mental health issues and suicide prevention, including the accessibility of resources, interventions, treatment facilities, emerging scope for education, and research. Although not planned as a research study, its noted effects on people have paved the way for implementing a local evidence-based community intervention. Future anti-stigma initiatives should integrate systematic research methods alongside cultural considerations to enhance mental health literacy. Hence, campaigns like “Mental Health Santhe” can promote mental well-being, dispel myths and misconceptions about mental health and reduce the treatment gap. The “Mental Health Santhe” initiative will emphasize incorporating robust statistical methodologies in upcoming editions. This strategic shift aims to bolster the initiative’s efficacy by enabling more accurate data collection and analysis, thereby providing valuable insights into the event’s impact on mental health awareness and help-seeking behaviors.

Hence, campaigns like “Mental Health Santhe” can promote mental well-being, dispel myths and misconceptions about mental health and reduce the treatment gap. The “Mental Health Santhe” initiative will emphasize incorporating robust statistical methodologies in upcoming editions. This strategic shift aims to bolster the initiative’s efficacy by enabling more accurate data collection and analysis, thereby providing valuable insights into the event’s impact on mental health awareness and help-seeking behaviors.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The funding for organizing the event was received from Dr. R N Moorthy Foundation for Mental Health and Neurosciences, NIMHANS.

References

- 1.Patel V, Minas IH, Cohen A, et al. Global mental health: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 401–417. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh OP. Closing treatment gap of mental disorders in India: opportunity in new competency-based Medical Council of India curriculum. Indian J Psychiatry, 2018; 60: 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlson FJ, Baxter AJ, Cheng HG, et al. The burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: A systematic analysis of community representative epidemiological studies. Lancet, 2016; 388: 376–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy RS. National Mental Health Survey of India 2015–2016. Indian J Psychiatry, 2017; 59: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The World Health Report: 2001: Mental health: New understanding, new hope. 2001. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42390

- 6.Mascayano F, Armijo JE and Yang LH. Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in low- and middle-income countries. Front Psychiatry, 2015; 6: 38. 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne P. Psychiatric stigma: Past, passing and to come. J R Soc Med, 1997; 90: 618–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Health education: Theoretical concepts, effective strategies, and core competencies: A foundation document to guide capacity development of health educators. 2012. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/119953

- 9.Yang LH, Thornicroft G, Alvarado R, et al. Recent advances in cross-cultural measurement in psychiatric epidemiology: Utilizing ‘what matters most’ to identify culture-specific aspects of stigma. Int J Epidemiol, 2014; 43: 494–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirmayer LJ, Pedersen D. Toward a new architecture for global mental health. Transcult. Psychiatry, 2014; 51: 759–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]