Abstract

Background:

Social-cognitive skills training (SCST) in a therapeutic setup can result in more positive outcomes when incorporated with psychotherapy, especially among adolescents with minor social-cognitive impairments in their social interactions. It may result in multifarious benefits to mitigate their social-cognitive dysfunction. This study aimed to identify the effects of SCST on interpersonal understanding of social norms in adolescents with low social cognition.

Methods:

In this quasi-experimental research, 80 adolescents (10–19 years) with low social cognition, no previous experience of skills training, and absence of any psychological disorders, especially those that affect their social-cognitive functioning, with assent from the participants and written informed consent from the parents/guardian and a score below 58 on the Need For Social-Cognition Scale, were included. They were randomly allocated into SCST or waitlist control group. SCST consists of 20 sessions with indoor activities, games, and discussions, and it has been arranged for 1 hour per 3 days a week for 3 months. Edinburgh social cognition test (ESCoT) was used to assess the degree of interpersonal understanding of social norms among adolescents as part of pre and posttests.

Results:

The Wilcoxon Sign Ranked Test showed that the interpersonal understanding of social norms after SCST is significantly higher than the interpersonal understanding of social norms SCST with a large effect size. The mean (standard deviation) scores in the ESCoT test improved significantly (P < 0 .001) following [W = 0.001, P < .001, r = –1.000].

Conclusion:

SCST effectively improves the interpersonal understanding of social norms, an essential developmental milestone during adolescence. It highlights the importance of focusing on mental health as a developmental asset that can influence social-cognitive development in the future.

Keywords: Mental health, social cognition, adolescence, interpersonal understanding, social norms

Key Messages:

Social Cognitive Skills Training (SCST) is an umbrella term for social-cognitive interventions focused on rehabilitating individuals with social cognition deficits. It usually includes various aspects of practicing social stimuli and learning strategies.

Though social cognitive skill training exists, literature shows that they are not being efficiently implemented and promoted, resulting in considerable mental health problems and adjustment issues that impact both the cognitive and social functioning of adolescents.

Introducing SCST aimed at bolstering social cognitive skills in adolescents exhibiting minor deficits could act as a proactive measure to mitigate the risk of future psychopathologies while nurturing their psychological well-being.

India has the largest adolescent population in the world. 1 Recent research underscores that one in seven Indian adolescents is seriously affected by mental health issues of various severity. 2 The general estimation of the proportion contribution of mental illness to the entire disease burden in our country has doubled since 2000. 3 This indicates a significant need to reach out to this segment to foster their interpersonal understanding of social norms and, thus, their social and cognitive well-being. 4 However, adolescents are required to handle several challenges in social life. Social-cognitive skills have become inevitable in successfully managing their social world today. Social cognition is the ability to acquire successful outcomes from mature social interactions in the community and family. 5 Social cognition is also critical in considering the thoughts, motives, desires, needs, feelings, and experiences that other people may have. Thinking about how these mental states can influence people’s actions is critical to forming social impressions and explaining how and why people do what they do. Low social cognition diminishes these abilities, especially interpersonal understanding of social norms. 6 This condition may lead to low social cognition, especially among adolescents. There are two significant reasons for focusing this study on the adolescent population. First, adolescence (10–19 years) is a crucial period for developing social and emotional habits other than any other period of human development.7, 8 This is when they usually encompass rapid physical and social-cognitive development. 7 These developmental aspects are essential for the mental health of individuals in this category. These include adopting healthy relationships, enhancing social interaction, developing coping, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills, and learning to manage emotions. 8

Second, there are precise pieces of evidence from previous research that the most common mental illnesses such as anxiety, affect, mood, attention, and behavior disorders are most likely to onset in the period of adolescence. 9 Adolescence (10–19 years) in lifespan development is a vulnerable time for the onset of severe mental health conditions. 10 It is because of the rapid change they undergo in cognitive, biological, psychological, social, and environmental areas of development. 11 Thus, social-cognitive processes are crucial to achieving an interpersonal understanding of social norms.

Interpersonal understanding of social norms in the theory of mind (ToM) is one of the essential variables studied in this research. Generally, social norms are cognitive representations of what others, often called reference groups, would typically think, feel, or do in a given situation.12, 13 These conventions and norms may involve face-to-face communication with those we talk and interact with and not to interrupt someone already engaged in interaction. 14 Interpersonal understanding of social norms is defined as an individual’s ability to process, navigate, and comprehend the rules and norms governing social interactions in a particular group. 15 This also involves identifying and respecting norms, rules, values, and customs that build adolescents’ social behavior and cognition. 16 Social perception is a connecting domain that helps decode and interpret social cues. These cues include verbal messages, verbal communications, paralinguistic information like tones, etc. It integrates contextual information and social knowledge into judgments about other’s behaviors. 17

Interpersonal understanding of norms is an essential aspect of social intelligence among adolescents. 18 It promotes adolescents’ social well-being, building positive social relationships, navigating social interactions, and contributing to a healthy social environment.19, 21 Positive social relationships and interactions directly affect adolescents’ mental health. Poor interpersonal skills can influence their socio-cultural and psychological development and lead them to engage in nonsocial activities such as alcoholism, substance abuse, and delinquent behavior. 22 Developing mature interpersonal skills will teach adolescents several areas of well-managed behavior, such as problem-solving, empathy, social responsibility, mind reading, proper communication, and autonomy.

This study was conducted to determine the effects of social-cognitive skills training (SCST) on Indian adolescents in improving their interpersonal understanding skills toward social norms and, thus, promoting their mental health in every aspect of their lives. Other than interpersonal understanding of social norms, this study also focuses on the ToM and intrapersonal understanding of social norms because social-cognitive skills focus on these domains, too. 23

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

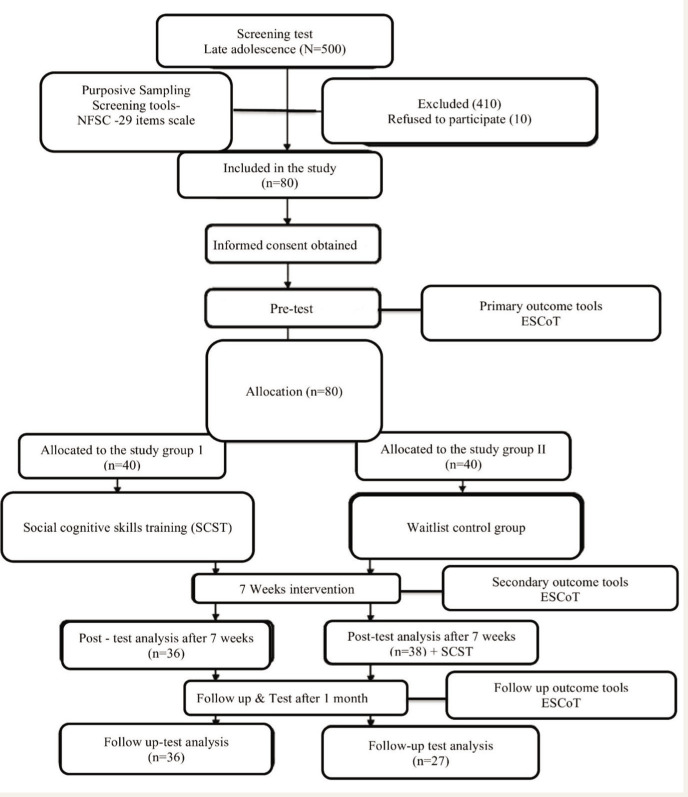

The participants underwent a screen test to identify the participants with low social cognition. Adolescents aged 10–19 years from three states, Kerala, Karnataka, and Tami Nadu of India, underwent screening tests from January 2023 to April 2023. This was to identify those adolescents with minor issues in the interpersonal understanding of social norms using the Need for Social Cognition (NFSC) 29-item scale.24, 25 The purposive sampling method is used for screening tests. It was noted during the analysis of screening data that most of the low scores in NFSC fall on late adolescents aged 17–19, which was why this study participant narrowed down the participants to those under this age category. Those with low scores on NFSC and who signed consent for the training were selected and allotted randomly (simple random sampling) for the final study. The sample size for the final study included 80 adolescents with low scores in interpersonal understanding of social norms. They were placed into two groups equally, ensuring informed consent and assent from participants and their parents were obtained. A quasi-experimental design with pretest and posttest methods was used in this study (Figure 1). Two qualified clinical psychologists with 5 years of experience in this field administered the SCST. Inclusion criteria included adolescents with low social cognition scores below 58 (average score) on the NFSC—and those with a written consent form. Adolescents with a previous history of mental illness and those who have participated in any life skill training program are excluded from this study.

Figure 1. Quasi-experimental Design of the Study.

The primary objective of the study was to identify the effects of SCST on adolescents’ interpersonal understanding of social norms. Thus, the hypothesis has accordingly been that SCST will improve interpersonal understanding of social norms.

Sample Size Estimation

After SCST, a mean change in the Edinburgh social cognition test (ESCoT) is observed, and it is considered a relevant factor with a 5% significance level (α = 0.05). Each group’s estimated sample size is 40, and we expect a 5% % to 10% dropout.

Tools

Consent Form and Demographic Data Sheet

The participants were given a consent form that debriefed the nature of the SCST program and other essential study details. They were requested to fill out the demographic sheet with information on age, gender, and other domains. Participants in the waitlist control group (WLCG) were offered SCST soon after completing the entire cycle of the research study, and it was mentioned in the consent form as an ethical obligation.

Need for Social Cognition (NFSC) Scale 25

‘NFSC’ is a 29-item scale introduced by Carpenter and Green in 2009. This tool is used in screening tests to assess adolescents’ social cognition needs, such as interpersonal understanding of social norms. Rating is made on a four-point scale, where 0 indicates no reference to internal states, and 3 indicates deep acknowledgment and exploration of mental states.’ ‘The NFSC focuses on a particular type of mental effort, specifically theorizing about other people’s mental states. The 29 items of the NFSC’ have internal consistency reliability with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70, interpreted as an adequate ‘level of reliability’ between the items. 25

Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT) 23

ESCoT was used as the outcome measure in the study. The ESCoT is a new test to assess social cognition in four domains: affective ToM, cognitive ToM, and inter and intrapersonal understanding of social norms. This study exceptionally focuses on a single domain among these four, that is, interpersonal understanding of social norms, because of the essential role of this domain during adolescence. ESCoT uses ten animated interactions. It measures four social-cognitive abilities related to social cognition. The ESCoT has 11 dynamic, cartoon-style social interactions, each approximately 30 seconds long. The ESCoT proves its inter-rater reliability using intra-class correlation assessment. The consistency of ESCoT assessed (ICCs) for the 15 ratings is 0.90, indicating high inter-rater reliability. Guttman’s Lambda 4 reliability coefficient calculates the assessment of the internal consistency of the ESCoT.

Procedure

Eighty adolescents who had met the screening criteria were selected for the study and randomly allotted to the experimental and WLCGs (40 in each group). As part of the ethical consideration, informed consent and assent were obtained from the participants and their parents. The researcher received ethical clearance from the ethical committee (CU: RCEC/00391/01/22), Department of Psychology, Christ University, Bengaluru, Karnataka. The SCST was done in the counseling department of a junior college setting, where students can easily use the language lab to use the visual and audio aids as part of their training.

With the help of ESCoT, it was administered to assess interpersonal understanding of social norms, and the scores were noted as part of the pretest and posttest. The experimental group was given SCST, and the WLCG participants had training once they completed the entire study cycle. Once the posttest was completed, the participants of the WLCG also received the full SCST sessions, and after a month of SCST, they were included in the follow-up and further assessments. The experimental group also received the same 5-day short-term follow-up scheduled after a month of the posttest, with a 1-hour session per day. Group discussions, debriefing, sharing experiences, and observation characterized it.

The SCST Intervention

The SCST given to the participants was focused on interpersonal understanding of social norms, an essential domain of social-cognitive skills. It consisted of five different sections with four sub-sessions in each section. The training program was conducted more than 2 months, three weekly sessions, and 40–45 minutes were taken for each session. Homework and feedback followed the training, and participants were cared for according to their needs. These sessions focused on intrapersonal understanding of norms, including awareness of their emotional states, feelings, and motivations. The social cognitive skills training (SCST) training program included activities, games, discussions, role-play, and brainstorming based on the social cognitive training for adolescents developed and validated by the researcher and the experts in this field. 23 A detailed description of the 5-day SCST session is available on the website 26 and is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

SCST Regime.

| Description of the SCST intervention for Interpersonal skills | |

| 1. | Participants had to fill out a questionnaire for self-assessment of communication skills. |

| 2. | Role-play learning nonverbal cues Participants are divided into four groups. Each group is provided with a familiar story or social scenarios secretly. Asked them to enact it without using verbal language so that others could identify the story’s theme. |

| 3. | Whispering game—Invited eight volunteers and assign every volunteer a number (1 to 8). Out of the eight volunteers, request six to be moved out of the room (3 to 8). Hand over the story to volunteer No. 1 and ask her/him to read and memorize it. Position two chairs facing each other inside the room. Volunteer no. 2 to call volunteer no. Three were waiting outside the room. Volunteer no. 1 to sit on one chair, and volunteer no. 3 to sit on the other chair facing Volunteer No. 1. Volunteer No. 1 narrates the story, and Volunteer No. 3. listens carefully. (Volunteers will narrate the story only once). Volunteer no. 1 to go back to his/her seat. Volunteer no. 2 to call volunteers no. 4, 5, 6, 7 & 8. Each pair to repeat steps 6, 7 & 8. (The story may be distorted to some extent). All the volunteers are to return to their respective seats. |

| 4. | Teamwork—Pair off group Ask the speaker to describe the geometrical image in detail. Based on the instructions, the drawer will attempt to recreate the image on their blank paper. Neither member can see the other’s paper, and the listener may not communicate with the speaker. They recognize what makes communication effective |

| 5. | Interpersonal Relationship—Informed participants that they will come up with a list of ingredients for a good relationship as a group. Informed them that each group will be given a worksheet of ‘the relationship recipe.’ They had to list at least ten ingredients for making a good friend. For example, A teaspoon of Icindness,500gm of helping, etc. For each ingredient, each had to write an example of how they could demonstrate that ingredient. |

Statistical Analysis

Once training was completed, the dropout number was noted from each group, and posttests were conducted. We have given training in three different junior college settings over almost the same period, collected data, and put it together for analysis. The SPSS software was used for data analysis, and the data were tested for normality. An independent sample t-test tested baseline differences between the experimental and WLCGs and found no differences. It was found that data were not normally distributed, and thus, a Wilcoxon Sign Ranked Test was used to obtain group effects. Four of them from the experimental group and two from the WLCG dropped out during this study. They were eliminated from the further analysis, and in the end, 36 participants remained in the experimental group, and 38 participants in the WLCG (a total of 74 participants) underwent post and follow-up tests.

Results

This study provides descriptive statistics on the details of variables (Table 2), followed by tests for the normality of all the variables for both the experimental and control groups. The baseline characteristics of the participants in both groups were similar. The majority of the participants were between 17 and 19 years old. The male-female proportion was maintained at 50%–50%.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the Demographic Factors (N = 74).

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | Range | |

| SCST group Age |

Male | 18 | – | – | – |

| Female | 20 | – | – | – | |

| 17.83 | 0.811 | 2 (13–19) | |||

| WLCG Age |

Male | 18 | – | – | – |

| Female | 18 | – | – | – | |

| 17.92 | 0.818 | 2 (13–19) | |||

| Total | Male | 36 | – | – | – |

| Female | 38 | – | – | – | |

| 74 | 17.88 | 0.810 | 2 (13–19) |

SCST group, Social-cognitive skills training group; WLCG, Waitlist control group.

The study’s primary objective was that SCST would improve Interpersonal understanding of social norms.

The Wilcoxon Sign Ranked Test result (Table 3) explains that for the adolescents in the experimental group (N = 36), the Interpersonal Understanding of Social Norms After SCST Program (M = 25.6, SD = 1.50, Mdn = 26) is significantly higher than the Interpersonal Understanding of Social Norms Before SCST Program (M = 20.7, SD = 1.65, Mdn = 20) with large effect size, W = 0.001, P < .001, r = –1.000. Similarly, the adolescents in the WLCG (N = 38), those without SCST, the Interpersonal Understanding of Social Norms (M = 20.4, SD = 1.06, Mdn = 20.0) does not significantly differ from the Interpersonal Understanding of Social Norms in the posttest (M = 20.8, SD = 1.33, Mdn = 21.0) with a medium effect size, W = 233.5, P = 0.065, r = 0.437. As evidenced by the results obtained from the pre and posttests of the experimental and WLCG participants, the experimental group showed a significant improvement in interpersonal understanding of social norms after SCST. In contrast, the WLCG showed no significant improvement in the interpersonal understanding of social norms. Thus, the results indicate that the SCST program positively affects adolescents’ Interpersonal Understanding of Social Norms in the experimental group.

Table 3.

Wilcoxon Sign Ranked Test Showing the Effectiveness of SCST on Interpersonal Understanding of Social Norms.

| Groups | Pretest | Posttest | W | P | r |

| Med (M, SD) | Med (M, SD) | ||||

| Experimental | 20 (20.7, 1.65) | 26 (25.6, 1.5) | 0.001 | <.001 | –1 |

| Waitlist control | 21 (20.8, 1.33) | 20 (20.4, 1.06) | 233.5 | 0.065 | 0.437 |

Dependent variable: Interpersonal understanding of social norms.

Med, median; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; W, Wilcoxon sign rank coefficient; p, probability; r, rank bi-serial correlation.

Discussions

This study was conducted with a major objective: SCST positively impacts the interpersonal understanding of social norms of adolescents’ development. As evidenced by the literature, the results showed a significant difference between the experimental and WLCGs. The participants in the experimental group who received SCST showed substantial improvement in their interpersonal understanding of social norms, which was higher than the participants who scored in the WLCG. The outcome indicates that SCST can improve social-cognitive skills in adolescents’ interpersonal understanding of social norms. Though the SCST was given to the participant on all four domains of social cognition, this research focuses only on one primary domain, interpersonal understanding of social norms, because of the high interest in this area of research among adolescents. Adolescents can learn interpersonal skills essential for positive social interactions using the right training program, like the ones conducted in the study. 27 They became capable of interpreting social cues, namely verbal messages and paralinguistic information such as tones and nonverbal communication aspects. This session is also characterized by an adolescent’s ability to integrate contextual information and social knowledge. 13 Training on understanding social norms among adolescents can act as a basis that helps us to coordinate with others, which is essential to social inclusion when they enter into a new social environment and experience specific social and cultural changes. 28

The strength of this study is that it illuminates the various possibilities of using SCST among adolescents as a preventive, nonpharmacological remedy. SCST prevents adolescents from developing severe psychopathology in the future by empowering their intrapersonal understanding skills. Also, this study supports using SCST as a guide for psychologists, counselors, and practitioners in adolescent mental health to prepare them to develop social identities, relationships, and confidence.

Adolescents and their cognitive activities often develop within a particular social interaction context. 29 This study proves that social competence continues to progress into adolescence, and they have mastered a group of social- cognitive skills, which allow them to act as the partakers of the social dyads and community in interpersonal skills flow back and forth. However, SCST given to the adolescents in this study focused more on practical verbal and nonverbal communication skills, social interaction, and interpersonal relationship skills, including understanding how others feel and using this understanding to communicate more effectively.

As observed in this study, participants also became capable of making social decisions in a social environment. They played an inevitable role in sustaining relationships and coordinating social actions. 30 They observed an apparent shift in energy and mood after the SCS training; thus, they could work on their inferior feelings to present themselves in front of others. The SCST group demonstrated significant improvement in facial affect identification, social interactions, and interpersonal skills compared to the WLCG. 31 Conforming to social norms is often considered a good choice because collective knowledge tends to help individuals’ well-being. In India, interpersonal understanding of social norms aids adolescents in taking into account what most people do or think should be done. 32

Our study emphasizes that SCST improves the social skills of children and adolescents with minor social-cognitive deficits. 36 Interpersonal understanding of social norms as the inevitable part of social-cognitive skills interferes with social networks. Promotion and training on SCST skills foster mature social skills essential for adolescents’ interpersonal understanding. 33 Participants were interested in group activities and homework to connect and face society blamelessly. Longitudinal data and training studies reveal that adolescents increasingly understand social norms more significantly. This is because they have notable progress in their ToM development during adolescence. These abilities are reflected in their mastery of other social-cognitive skills in which adolescents are asked to read or predict others’ thoughts and beliefs. 34 The development of Social-cognitive skills depends on the maturation of brain systems, and it is shaped by training, parenting, education, and social relationships. Thus, the dense interaction between the brain and social environment is always a topic that needs more research. 35

The SCST among the participants gave more individual and group opportunities to learn interpersonal skills, which helped them better understand social norms in detail. Follow-up assessment highlights the long-lasting effects of SCST among adolescents on interpersonal understanding of social norms. As evidenced by the existing literature, adolescence encompasses more cognitive development than any other stage of life span in human development. Training based on interpersonal communication, nonverbal communication, social communication, and social relationship skills improves interpersonal skills among late adolescents. The follow-up study was considered the second validation of the effectiveness of SCST on interpersonal understanding of social norms. The data analysis on follow-up information proved that SCST can provide long-lasting positive effects on adolescents’ interpersonal understanding of social norms.

Limitations

The major limitation of the study is about generalization. Since this study concentrates only on adolescents, it will not explain the effect of SCST on other age categories. Another limitation was about social demographic details. It would be better to include more details about the social demographics of adolescents other than age and gender. The study’s cross-sectional nature limited the effects of SCST to a particular age group. Cultural differences from different states can also affect adolescents’ social-cognitive training. The range of attitudes adolescents from particular cultures embrace affects their beliefs, social actions, and lifestyles.

Implications of the Study

SCST is a good nonpharmacological form of training for adolescents that can be used with psychotherapy for the treatment of social-cognitive impairments that are generally seen in psychotic disorders. This training can be used mainly in adolescents as a systematic training method for improving their interpersonal understanding of social norms. SCST findings provide implications in clinical, counseling, and adolescent psychology. It provides significant insights into different adolescent functions, their nature, and their impact on social cognition and overall mental health. In India, the SCST is a unique and only available training program exclusively prepared for adolescents based on their social-cognitive abilities. The SCST training can be used as a manual for adolescent training in the future because it typically focuses on learning specific skills in understanding appropriate social norms, such as communication, empathy, perspective-taking, and mind-reading. This training can be used widely in schools, colleges, and other settings where adolescents gather. SCST can be a valuable tool for adolescents to improve their ToM skills, understanding norms, and psychological well-being.

For this reason, it helps reduce adolescents’ vulnerability to psychopathological conditions in the future. The SCST has various structured activities in each session. Different activities target different domains of social, cognitive, and affective functioning. However, improvement in one domain has a ripple effect and benefits across multiple domains. This study suggests conducting more such empirical studies in India. Screenings or assessments within communities or clinical settings should be performed to identify adolescents who may benefit from SCST. Adolescents across the world require improvement in their social-cognitive skills. This training can immensely benefit adolescents by preparing them for future social interactions, making relationships, and fulfilling their responsibilities.

Conclusion

The SCST is a comprehensive training program based on social-cognitive skills, and it supports the effectiveness of nonpharmacological approaches in mild social-cognitive deficits that affect the interpersonal understanding of social norms among adolescents in their later development. We affirm that this study demonstrates the feasibility of using this training program, which can be implemented as part of youth training programs in the future to enhance the inter-intrapersonal understanding of social norms. The current SCST study proves its effectiveness in improving the knowledge of norms, relationship skills, and verbal and noncommunication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dept. of Psychology at Christ University for their time-to-time guidance and input while preparing this research article, which gave its proper refinement.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Statement: The study participants obtained informed consent from both parents and students. The researcher obtained an IRB from Christ University’s research ethics committee (CU: RCEC/00391/01/22).

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Sagar R, Dandona R, Gururaj G, et al. The burden of mental disorders across India: the global burden of disease study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatry, 2020: 7(2): 148–161. 10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30475-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anisha. World mental health day 2020: in numbers, the burden of mental disorders in India. NDTV-Dettol Banega Swasth Swachh India, 9 October 2020. https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/world-mental-health-day-2020-in-numbers-the-burden-of-mental-disorders-in-india-51627/

- 3.Anilkumar BS. 60% of college students in Kerala suffer depression: study. The Times of India. 20 June 2021. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/thiruvananthapuram/60-of-college-students-suffer-depression-study/articleshow/83674534.cms

- 4.Junge C, Valkenburg PM, Deković M, et al. The building blocks of social competence: contributions of the consortium of individual development. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 2020; 45: 100861. 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.1008614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colarusso CA. Adolescence (ages 12–20). Springer eBooks. 1992, pp. 91–105. 10.1007/978-1-4757-9673-5_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frith CD. Social cognition. Philos Trans B, 2008; 363(1499). 10.1098/rstb.2008.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilford EJ, Garrett E and Blakemore, The development of social cognition in adolescence: an integrated perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2016; 70: 106–120. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehra D, Lakiang T, Kathuria N, Kumar M, Mehra S, Sharma S. Mental health interventions among adolescents in India: a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel), 2022. Feb 10; 10(2): 337. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10020337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cataldo I, Lepri B, Neoh MJY, et al. Social media usage and Development of Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence: a review. Front Psychiatry, 2021; 11. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.508595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis M. Exploring adolescence as a key life history stage in bioarchaeology. American J Biol Anthropol, 2022; 179(4): 519–534. 10.1002/ajpa.24615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santamaría-García H, Báez S, Gómez C, et al. The role of social cognition skills and social determinants of health in predicting symptoms of mental illness. Trans Psychiatry, 2020; 10(1). 10.1038/s41398-020-0852-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koski J, Xie H and Olson IR. Understanding social hierarchies: The neural and psychological foundations of status perception. Soc Neurosci, 2015; 10(5): 527–550. 10.1080/17470919.2015.1013223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steentjes K, Kurz T, Barreto M, et al. The norms associated with climate change: understanding social norms through interpersonal activism. Global Environ Change-human Policy Dimen, 2017; 43: 116–125. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris MW, Hong Y, Chiu C, et al. Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, 2015; 129: 1–13. 10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legros S and Cislaghi B.. Mapping the social-norms literature: an overview of reviews. Perspect Psychol Sci, 2019; 15(1): 62–80. 10.1177/1745691619866455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutet I, LeBlanc M, Chamberland J, et al. Emojis influence emotional communication, social attributions, and information processing. Comput Hum Behav, 2021; 119: 106722. 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams J, Fiore SM and Jentsch F.. Supporting artificial social intelligence with theory of mind. Front Artif Intell, 2022; 5. 10.3389/frai.2022.750763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umberson D and Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Social Behav, 2010; 51(1_suppl): S54–S66. 10.1177/0022146510383501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez-López M, Viejo C, Romera EM, et al. Psychological well-being and social competence during adolescence: longitudinal association between the two phenomena. Child Indic Res, 2022; 15(3): 1043–1061. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurizi LK, Grogan-Kaylor A, Granillo MT, et al. The role of social relationships in the association between adolescents’ depressive symptoms and academic achievement. Child Youth Serv Rev, 2013; 35(4): 618–625. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anttila K, Anttila M, Kurki M, et al. Social relationships among adolescents as described in an electronic diary: a mixed methods study. Patient Pref Adherence, 2017; 11: 343–352. 10.2147/ppa.s126327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baksh RA, Abrahams S, Auyeung B, et al. The Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT): Examining the effects of age on a new measure of theory of mind and social norm understanding. PLOS One, 2018; 13(4): e0195818. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam KF, Awal A, Mazumder H, et al. Social cognitive theory-based health promotion in primary care practice: a scoping review. Heliyon, 2023; 9(4): e14889. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavigne R, Cuenca AMG, Romero-González M, et al. Theory of mind in ADHD: a proposal to improve working memory through the stimulation of the theory of mind. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020; 17(24): 9286. 10.3390/ijerph17249286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter J. Need for social cognition: devising and testing a measurement scale [PhD dissertation]. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2009, pp. 47–49. https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/downloads/2227mq31t [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob L and Reddy J.. The development of a social cognitive skills training program (A-SCST) module for late adolescents on psychological well-being. 202341074643, 2023. Available from: https://iprsearch.ipindia.gov.in/PatentSearch/PatentSearch/ViewApplicationStatus

- 27.Serrano-Pintado I, Escolar-Llamazares MC and Delgado-Sánchez-Mateos J. Pilot study on the effects of the teaching interpersonal skills program for teens program (PEHIA). Front Psychol, 2022. Feb 11; 13: 764926. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.764926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrano-Pintado I, Del Camino Escolar Llamazares M and Delgado-Sánchez-Mateos J. Pilot study on the effects of the teaching interpersonal skills program for teens program (PEHIA). Front Psychol, 2022; 13. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.764926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang W, Liu Y, Dong Y, et al. How we learn social norms: a three-stage model for social norm learning. Front Psychol, 2023; 14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1153809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dennis M Simic N, Bigler ED, et al. Cognitive, affective, and conative theory of mind (ToM) in children with traumatic brain injury. Develop Cogn Neurosci, 2013; 5: 25–39. 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross J and Vostroknutov A.. Why do people follow social norms? Curr Opin Psychol, 2022; 44: 1–6. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim JE, Kwon Y, Jung SY, et al. Benefits of social cognitive skills training within routine community mental health services: evidence from a non-randomized parallel controlled study. Asian J Psychiatry, 2020; 54: 102314. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapinski MK and Rimal RN. An explication of social norms. Commun Theory, 2005; 15(2): 127–147. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bianco F and Castelli I.. Promoting mature theory of mind skills in educational settings: a mini-review. Front Psychol, 2023; 14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1197328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ebert S. Theory of mind, language, and reading: developmental relations from early childhood to early adolescence. J Exp Child Psychol, 2020; 191: 104739. 10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korkmaz B. Theory of mind and neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. Pediatr Res, 2011; 69(5 Part 2): 101R–108R. 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318212c177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]