Abstract

Background:

Youth in India carry a large proportion of the global burden of mental health disorders and subclinical distress. They prefer to seek mental health support from informal sources. One such source—online mental health peer-support forums (OMHPSFs)—is under-researched. This study aims to explore the perspectives of youth and mental health professionals and counselors (MHP&Cs) in terms of the scope and utility of and inclination to use OMHPSFs for maintaining youth mental well-being.

Methods:

An exploratory, cross-sectional, mixed-methods study was conducted. A total of 141 Indian nationals aged 18–29 years were enrolled using convenience sampling and administered a survey. In the qualitative phase, six youth and seven MHP&Cs were interviewed.

Results:

Ninety (63.8%) and 106 (75.2%) participants indicated a high inclination to use OMHPSFs to seek and provide support, respectively. More than three-quarters of the surveyed youth stated that OMHPSFs should be a space for emotional and informational support to deal with life challenges. A total of 127 (90.1%) participants reported that OMHPSFs would be useful to find out how others their age deal with similar life challenges. A thematic analysis of interviews revealed that anonymity, accessibility, appeal, and ease of use enhance youth inclination toward OMHPSFs. The role of MHP&Cs in training, supervision, and moderation and strategies to popularize OMHPSFs were outlined and recommended.

Conclusion:

Sampled youth showed a high inclination to use OMHPSFs to seek and provide mental health support to their peers. Stakeholders consider OMHPSFs as relevant in scope and utility to alleviate mental health concerns among Indian youth.

Keywords: Digital mental health, online mental health forums, online peer support forums, peer support, technology-based mental health interventions, youth mental health, youth mental health help-seeking

Key Messages

Sampled English-speaking urban Indian youth aged 18–29 years show a high inclination to use online mental health peer-support forums (OMHPSFs) to seek and provide mental health support.

Stakeholders opine that OMHPSFs can be a powerful tool to alleviate distress and enhance the psychological well-being of Indian youth if designed and implemented in ways that make forums accessible, appealing, anonymous, and easy to navigate.

Youth comprise 18% of the world’s population; 1 one-third of this statistic comes from India.2,3 Young persons heavily bear the global burden of mental illness; the lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders is nearly 10% among Indian youth.4,5

The mental health (MH) treatment gap stems from multiple factors, namely, scarcity of trained professionals,6,7 low budgetary allocations to the MH sector that perpetuate infrastructural deficits, 8 and barriers to seeking MH support, which include stigma, fear of ostracization, resource constraints, doubts about treatment effectiveness, trivialization, poor identification of mental illness, and misattribution to magico-religious factors.9–15

Although informal community care and self-care—the lowermost rungs of the WHO’s Pyramid of Care model 16 —rank high on large-scale utility and need and low on provision costs, systems that support such care are least developed. This necessitates the strengthening of informal care infrastructure to cater to the MH needs of distressed, treatment-non-seeking Indian youth. 17 Research shows that youth prefer informal sources of MH support;17,18 online social networking sites (SNSs) have emerged as prime spaces enabling distressed youth to overcome impediments to MH care by providing anonymity, control, and immediacy.19,20 Accessible, affordable internet facilities have sprouted online peer-support groups and forums on existing SNSs such as Reddit 21 and Facebook. 22 Moreover, full-fledged websites are now devoted entirely to providing peer-to-peer MH support, such as 7 Cups 23 and Beyond Blue. 24 The former is a service that connects help-seeking users with peer-support providers in a one-on-one chat room setup. The latter offers online MH services, including an online mental health peer-support forum (OMHPSF). An OMHPSF refers to an online discussion website where users can upload solely textual content seeking support for MH concerns and psychological distress, on which other users (peers) who have similar lived experiences can provide informational/emotional/relational MH support in the form of public text-based comments to enhance the mental well-being of the support seekers.25,26

Moderated OMHPSFs for youth have been shown to benefit both support providers and receivers in the pool of literature that emerges largely from high-income countries.27–30 Youth respondents in these studies commonly emphasized the benefits of engaging on such forums, such as feeling understood and like they belong and being listened to by those similar.31–33 Additionally, they pressed for a qualified moderator to ensure safe online interactions and listed forum design features such as anonymity and visual appeal to enhance its popularity.33–35

To the extent known, two mental health online forums were launched and functional in India—one is Psych-care Peer Support, an OMHPSF launched for Indian youth during COVID-19, and the other is managed by YourDOST, an online mental health services platform. Saha and their colleagues 36 recently discussed the setting-up process of Psych-care Peer Support. Limitations of the platform alluded to poor awareness of its existence among youth, language restrictions, and a disproportionate visitor-to-poster ratio.

There is a severe lacuna of relevant OMHPSF research emanating from the Indian subcontinent and on the utilization of OMHPSFs, specifically with the youth population. However, Indians and youth constitute the largest internet user bases globally.37,38 MH professionals form another category of stakeholders whose perspectives on various aspects of OMHPSFs must be understood and incorporated into practice. All of these set the agenda for inquiry in the present study.

This study, therefore, aimed to explore the perspectives of youth and MH professionals and counselors (MHP&Cs) in terms of the potential scope and utility of and inclination to use OMHPSFs for maintaining mental well-being and addressing common youth MH concerns as support seekers and providers. The study’s secondary objectives were to document stakeholder preferences for design features of OMHPSFs to enhance inclination, the role of MHP&Cs on OMHPSFs, and to generate strategies to popularize OMHPSFs among youth.

Methods

Design and Participants

A mixed-method, exploratory, cross-sectional study design was adopted. The quantitative phase sample comprised 141 Indian nationals aged 18–29 years with a minimum of 10 years of formal education and the ability to read and write English, enrolled using a convenience sampling strategy. A flyer with a call for research participants, a clickable Google Forms link, and a scannable QR code directing interested individuals to the online survey were circulated on popular SNSs. The qualitative phase sample was a subset of the survey sample: six participants who indicated moderate to high inclination to use OMHPSFs and having had prior engagement on similar platforms were purposively selected to elicit their perspectives based on their experience as users on similar forums. Purposive sampling was also employed to enroll seven MHP&Cs having at least three years of research and/or practice experience in digital, community, and/or youth mental health or having served as moderators on similar mental health forums—to elicit expert opinions and perspectives on the scope of and operating OMHPSFs based on their professional forum experience.

Description of Tools and Measures

Socio-demographic Datasheet

This section was devoted to procuring information about respondents’ age, sex, education level, occupational and marital status, religion, and current living arrangements. Items to gauge current stress levels, recent major life events, sources and levels of use of mental health support, and subjective distress and well-being concerns were included.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)

K10 was employed to obtain a global measure of distress in the most recent four-week period on 10 items with 5 options, ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time.” Severity cut-offs provided by Andrews and Slade were used.39,40

OMHPSF Survey

An OMHPSF is a public website that allows the user to read and respond to others’ questions and post one’s own MH queries to get support or suggestions for dealing with one’s life concerns and challenges from others with similar experiences and of a similar age. An OMHPSF usually supports text-based posts and responses; these are not one-on-one, thereby allowing all users to respond to all posts.25,26

The OMHPSF survey items were developed based on the reviewed literature and in alignment with the objectives of the present study. A paragraph describing an OMHPSF for youth—as defined above—was presented at the start for uniformity in comprehension. To elicit the inclination to seek and provide help on OMHPSFs, two items with Likert-type options ranging from “Highly Unlikely” to “Highly Likely” were included. The scope, perceived utility, and preferred design features of OMHPSFs were captured using a checklist-type item, with options generated from the reviewed literature; respondents could endorse more than one option. A mix of Likert-type and open-ended items was used to assess the frequency of visits and postings on existing forums like the one described in the survey and ideas for popularizing OMHPSFs among youth.

Semi-structured Interview with the Youth Subsample

Interview probes were used to gauge youth’s prior use and experience of posting their concerns or responding to others’ posts on existing forums, factors that enhance their inclination to use OMHPSFs as support seekers and providers, preferred design features of OMHPSFs, and felt needs of youth to enhance their inclination to use OMHPSFs. Strategies to popularize forums among Indian youth were further explored.

Semi-structured Interview with MHP&Cs

Semi-structured interview probes were used to elicit MHP&Cs’ perspectives on common mental health concerns of youth; barriers to help-seeking and the role of technology in bridging the gap; the utility, scope, and design features of OMHPSFs to enhance inclination; and the role of MHP&Cs in OMHPSFs in training and supervision through extended guidance and moderation. MHP&Cs were invited to suggest strategies for enhancing the utility, appeal, and reach of OMHPSFs among youth.

Procedure

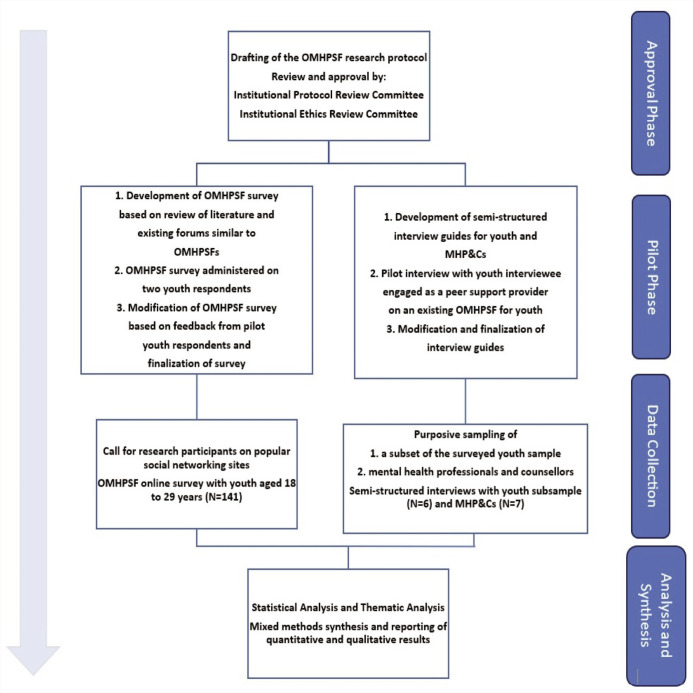

The study was carried out in phases, as illustrated in Figure 1. The Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study. Data collection spanned from February to May 2022.

Figure 1. Study Procedures.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis of survey data was done to assess frequencies, percentages, and the association of age, gender, and psychological distress levels with the inclination to use OMHPSFs on IBM SPSS Statistics 20. The normality of continuous variables was examined using the K-S Z test. A chi-squared test of association between categorical variables and correlation was used to analyze the nature of relationships between stress and distress levels with an inclination to use OMHPSFs for seeking and providing support and to examine the association of past visits to and history of posting online forums with an inclination to seek and provide help on OMHPSFs. A thematic analysis of qualitative data obtained from phases two and three was conducted. Common, recurrent ideas emerged; codes were extracted from the interview transcripts and organized into overarching themes. Qualitative findings were compared, contrasted, and synthesized with survey results.

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics

A total of 141 participants between the ages of 18 and 29 were enrolled in the quantitative survey phase. Age, gender, and occupation were roughly equally represented (Table 1).

Table 1.

Youth Survey Sample Characteristics ( N = 141).

| Variable | Sub-variable | Frequency | Percentage |

| Age | 18 to 23 | 81 | 57.4 |

| 24 to 29 | 60 | 42.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 64 | 45.4 |

| Female | 77 | 54.6 | |

| Education | 12th std. | 22 | 15.6 |

| UG/Diploma | 58 | 41.1 | |

| Post-graduation | 61 | 43.2 | |

| Occupational status | Employed full time | 51 | 36.1 |

| Employed part time | 06 | 04.2 | |

| Searching for employment | 07 | 04.9 | |

| Self-employed | 07 | 04.9 | |

| Student | 70 | 49.6 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried and single | 102 | 72.3 |

| In a committed relationship | 31 | 21.9 | |

| Married | 07 | 04.9 | |

| Divorced | 01 | 00.7 | |

| Religion | Hinduism | 83 | 58.8 |

| Islam | 10 | 07.1 | |

| Christianity | 24 | 17.1 | |

| I do not follow any religion | 23 | 16.3 | |

| Others | 01 | 00.7 | |

| Current living arrangement | Staying alone | 09 | 06.3 |

| Living with family | 82 | 58.1 | |

| In a hostel/PG | 33 | 23.4 | |

| Living with flatmates | 17 | 12.1 |

Youth Stress, Distress, and Help Seeking

About three-fourths (N = 97) of the surveyed youth reported having experienced a major stressful situation in the recent past, stemming from academics (46%), work (33%), and family (34%). This was in line with themes that emerged in the interviews, as described by an MHP&C: “Often [concerns of youth] go into the realm of relationships, particularly with significant others, or parental relationships. Even career—starting their careers, switching careers, and related academic difficulties.” While analyzing responses marked as “Others,” issues revolved around romantic and marital relationships.

On K10, around 65% of surveyed youth had a score above 20 (“mild,” “moderate,” and “severe”), indicating the presence of psychological distress (Table 2). More than half (58.2%) reported high subjective stress levels (above 8 on a scale of 1–10). In response to an item on subjective experience of distress, nearly 50% of the sample (N = 61) reported either persistent low mood or anxiety for more than a week at least once in the preceding six months.

Table 2.

Distress Level of Participants on the Psychological Distress Measure.

| Psychological Distress Scale (K10) | Frequency | Percentage |

| Likely to be well | 50 | 35.4 |

| Mild | 30 | 21.2 |

| Moderate | 31 | 22.3 |

| Severe | 30 | 21.2 |

| Mean | 23.6 | |

| SD | 7.8 |

In response to an item to indicate sources of MH support and the extent to which each was used (“Used Quite a Lot” to “Not Used”), more than half of the surveyed sample reported seeking help frequently from friends (60.9%) and parents (44.6%). The least used sources were general practitioners (2.8%) and phone helplines (2.1%); 5% listed online forums as a source of support.

These findings corresponded to what interviewed youth cited as barriers to seeking help, phrased as “not knowing where to go or whom to go for help.” Others mentioned the unaffordability and inaccessibility of professional help: “We are all strapped for cash, and asking for money from your parents to go to a professional is just not done. So, we end up with social media, talking to a friend, or just dealing with it alone.”

Scope and Utility of OMHPSFs for Youth

In response to the survey item about the scope of OMHPSFs (Table 3), asking respondents what they think should be provided on OMHPSFs, sampled youth preferred OMHPSFs to be a space for emotional (79.4%) and informational support (74.5%) to deal with common mental disorders and life challenges. The least endorsed option was OMHPSFs as a space that links youth to professional help (20.5%). Interviewed youth endorsed similar views, additionally suggesting that well-being promotion be included in the scope, stated as follows: “it [should] focus not only on illness … but also different ways of increasing wellbeing, like activities for youth.” An MHP&C mentioned, “It can include information on programs conducted for youth which aim at inculcating positive mental health and not simply symptom reduction.” This aligns with survey responses to the item about the subjective experience of distress and well-being concerns of youth, in which three-quarters (75.2%) endorsed the statement, “I have felt the need to work on self-improvement in one or the other area of my life.”

Table 3.

Perspectives of Surveyed Youth on the Scope of OMHPSFs.

| Sl. No. | Scope | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1 | Emotional support for dealing with common issues in youth such as depression and anxiety symptoms | 112 | 79.4 |

| 2 | Information on services and resources for dealing with common issues such as depression and anxiety | 105 | 74.5 |

| 3 | Information to help make decisions in various areas of life, such as academics/career | 92 | 65.2 |

| 4 | Emotional support for coping with common life situations, challenges, and dilemmas faced by youth | 105 | 74.5 |

| 5 | Tips and views of peers (youth of similar age) about dealing with stressful life situations | 103 | 73 |

| 6 | Support/guidance and motivation in deciding about seeking professional help for one’s issues | 29 | 20.5 |

OMHPSF, Online Mental Health Peer Support Forum.

Youth respondents were asked what they think would be useful on OMHPSFs and to what extent (Table 4). Nearly 90% stated that OMHPSFs would be “very useful” to know whether others their age had similar experiences and how to deal with them, that is, finding solutions to one’s problems vicariously, as described by a youth interviewee as follows: “Most of the time, I do not post at all. I just go there and see that somebody is … having a concern similar to me. I read what others have commented on and how others have helped out. Furthermore, that make[s] me go through, like, a Eureka aha moment, you know?”

Table 4.

Perspectives of Surveyed Youth on the Perceived Utility of OMHPSFs.

| Sl. No. | Utility | High* | Low* | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| 1 | For receiving relevant factual information on an issue | 117 | 82.9 | 24 | 17.02 |

| 2 | For receiving emotional comfort and support about one’s experience, which is difficult to share face-to-face | 120 | 85.1 | 21 | 14.8 |

| 3 | For gaining a fresh perspective from others of similar age on how to handle a situation | 126 | 89.3 | 15 | 10.6 |

| 4 | For getting suggestions and advice | 116 | 82.2 | 25 | 17.7 |

| 5 | For finding out whether others of my age have had similar experiences and how they deal with it | 127 | 90.07 | 14 | 9.9 |

| 6 | For getting feedback from persons of my age about my ideas on dealing with a stressful situation | 115 | 81.5 | 26 | 18.4 |

*Responses “Very useful” and “Somewhat useful” were grouped as “High utility,” and responses “A little useful” and “Not useful” were grouped as “Low utility” in terms of how useful an online peer support forum may be perceived for various purposes listed.

OMHPSF, Online Mental Health Peer Support Forum.

A close second (89.3%) option was that of gaining a fresh perspective on relevant matters, which also emerged as a theme—youth interviewees asserted that OMHPSFs would be deemed useful to find new ways of looking at the problem: “I was very confused because in Kerala, or I think in any household for that matter [laughs], arts are so taboo. That is when I went on Quora, I think … and I saw so many others who had recently begun their UG or 11th in arts … hear[ing] about their experiences and decisions was very good for me. After that, I started typing random topics in the Quora search button, such as, ‘How do you tell your friend that you are upset with them?’ or ‘How do you solve some problem?’ something like that … I could see so many different answers and ways of looking at the same thing, no? Nothing felt like a dead-end anymore when all of this I could get with only one fast click.”

A theme related to the perceived utility that was not captured in the survey was that of relatedness and a sense of not being alone, phrased by a youth interviewee in this manner: “… going on to this online forum and getting to read other people—especially those of my age—having the same struggles as me? Well, that, I think, in itself was so … therapeutic for me. I felt understood, I felt heard. I felt I was no longer, I do not know, pretending, if [I] can put it that way.”

Inclination to Use OMHPSFs to Seek and Provide Help

Three-fourths of the surveyed youth indicated a high inclination to provide help on OMHPSFs (75.2%), whereas a little more than half (63.8%) indicated a high inclination to use OMHPSFs to seek help (see Table 5). There was a statistically significant positive, albeit weak, correlation between psychological distress assessed on K10 and inclination to seek help on OMHPSFs (r = 0.18, p < .05).

Table 5.

Inclination of Surveyed Youth to Use OMHPSFs to Seek and Provide Help.

| Inclination to Seek Help on OMHPSFs | Frequency | Percentage |

| Extremely unlikely | 11 | 7.8 |

| Unlikely | 40 | 26.4 |

| Likely | 81 | 57.4 |

| Extremely likely | 9 | 6.4 |

| Inclination to Provide Help on OMHPSFs | Frequency | Percentage |

| Extremely unlikely | 9 | 6.4 |

| Unlikely | 26 | 18.4 |

| Likely | 82 | 58.2 |

| Extremely likely | 24 | 17 |

OMHPSF, Online Mental Health Peer Support Forum.

Stakeholder Recommendations to Enhance Youth Inclination to Seek and Provide Help on OMHPSFs

Interviewed youth elaborated on ways to strengthen their inclination to use OMHPSFs—the themes included ensuring accessibility, ease of use, anonymity, and appeal.

Youth and MHP&Cs strongly recommended that OMHPSFs be free to use. Online visibility was emphasized, as an MHP&C stated, “I Google it, and it should be right there on top. It makes it seem a little … not credible if it is so far down.” Throwaway accounts without needing registration using email or phone numbers were suggested for greater access, along with equipping the forum with plug-ins for regional languages. A few MHP&Cs appealed against throwaway accounts to ensure safety and credibility and to prevent online trolling and cyberbullying.

For enhanced ease of use, interviewees suggested that OMHPSFs be accessible on PCs and in mobile app formats. Youth and MHP&C interviewees generated myriad ideas, such as creating keyword tags for posts, categorizing posts as “read,” “unread,” and “most recent”, having sub-forums and chat rooms, and not making in-app purchases or advertisements.

To improve the appeal, youth pressed that “it needs to look cool and have a cool name,” appear clutter-free, and have space for free discourse such as commenting and getting feedback from support seekers.

Moderation by mental health professionals (86.5%) and anonymity (80.9%) were highly favored in both the survey and interview phases to attract and retain young help-seekers on OMHPSFs. Training (83.7%) and supervision (78%) of peer-support providers were highly recommended to enhance inclination, which coincided with the views of MHP&Cs in defining their role on such platforms. A few interviewees expressed concerns about having trained volunteer youth responders as it may compromise feelings of authenticity and relatedness—making the trained peer-support providers be perceived as different or as experts by support seekers rather than actual, relatable peers.

Interviewees suggested popularizing OMHPSFs through word-of-mouth strategies, social media influencers, and awareness programs about the forum in schools, colleges, and workplaces. Survey respondents suggested harnessing the reach of existing SNSs by having inter-app shareable plug-ins. They also stressed on aesthetic appeal and the presence of moderators as prerequisites to effective popularization strategy implementation.

Recommendations by MHP&Cs

MHP&Cs pressed against mixing peer support with professional consultations when asked to outline the scope of OMHPSFs: “…[it] should not venture into crisis support, and unfortunately, we do see many crisis posts on the forum. I do not think a forum should get into the business of trying to connect youth with professionals. Then it becomes, sort of, like a Tinder for therapists … I have mixed views on whether even a list of professionals should exist on the forum.” A few MHP&Cs drew attention to logistical issues that may arise in providing language options on OMHPSFs, such as the need for qualified moderators to be fluent in these languages. An MHP&C recommended that there be a disclaimer before a user registers on the site that lays down the ground rules of interaction on the forum: “No fake posts, no slurs, no swearing, no discriminatory or abusive language, etc. Maybe users, or more so posters, can indicate at the start of their post that there may be sensitive content such as self-harm or suicide with, maybe, a trigger warning.”

Most MHP&Cs favored free-flowing interaction on the platform and not a linear “question-answer” feature. However, one MHP&C raised a concern: “This may leave many posts unanswered, or even worse—wrongly answered. So, it would be important to find some balance.” There were mixed opinions on training youth support volunteers to respond to OMHPSFs instead of “a more organic, real peer-support interaction,” as an MHP&C phrased it. On the other hand, there was consensus among all MHP&Cs that OMHPSFs must be moderated by qualified MHP&Cs.

Results from Supplementary Analysis

One-third (34.7%) of the surveyed youth reported frequent visits to and posting on online mental health forums in the past, and 9.9% reported frequent postings on them. Supplementary analysis (Table 6) revealed a statistically significant association between frequent visits to and posting on online forums and an inclination to seek help on OMHPSFs.

Table 6.

Association Between Past Visits to and Posting on Forums with Inclination to Seek and Provide Help on OMHPSFs.

| Variable | Past Visits | χ2value | ||

| Low | High | |||

| Inclination to seek help |

Low | 41 | 10 | 8.08* |

| High | 51 | 39 | ||

| Inclination to provide help |

Low | 25 | 10 | .78 (NS) |

| High | 67 | 39 | ||

| Variable | History of posting | χ2value | ||

| Low | High | |||

| Inclination to seek help |

Low | 50 | 1 | 5.67* |

| High | 77 | 13 | ||

| Inclination to provide help |

Low | 32 | 3 | .09 (NS) |

| High | 95 | 11 | ||

*p < .05. NS, not significant.

Responses of “Never” and “Rarely” were categorized as “Low,” and “Sometimes,” “Often” and “Always” as “High” in terms of frequency of past visits to and posting on online forums.

OMHPSF - Online Mental Health Peer Support Forum.

Discussion

Stress, Distress, and Help-seeking Sources and Barriers of Indian Youth

In this study, more than three-quarters of the surveyed youth reported psychological distress levels higher than the cut-off and moderate levels of stress, stemming from academic difficulties, career troubles, and interpersonal conflict with family and romantic partners. These coincide with findings from recent Indian studies where 18–34%41,42 of college-going youth and young adults reported experiencing significant psychological distress due to feelings of inadequacy and high competition in academics,43,44 job insecurity, poor work–life balance and insufficient pay, 45 and fallouts in important relationships. 46 These would sometimes culminate in depression and anxiety47,48—further exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. 49

Youth in the study preferred to seek mental health support mainly from family and friends—labeled “natural helpers” 50 in social support literature—followed by informational websites and romantic partners, as they deemed this support accessible and affordable. Indian youth tend to seek help mainly from friends rather than families, as reported in other studies.18,51 Doubts of treatment effectiveness, misinformation, perceived peer norms, self-reliance, poor illness identification, and stigma serve as notable barriers to formal mental health support9-11—so much so that only 3%–9% of young people with emotional problems in India sought professional help. 52

OMHPSFs: Scope and Utility

While a few interviewees in this study reported wariness of online spaces for bridging the mental health treatment gap due to possible trolling and cyberbullying, most were in favor of developing technological infrastructure to harness the widespread use of mobile internet to connect platforms like OMHPSFs to those who need them the most. Indian consumers of online products are reported to be generally open to using mental health apps 53 ; international studies have shown that youth, in particular, have received online mental health forums and groups largely positively, which are associated with enhanced mental health literacy and help-seeking inclination.53–56

Many youth respondents in the study recommended that OMHPSFs be a space to seek and provide emotional and informational support to deal with daily life challenges and issues such as depression and anxiety. OMHPSFs as a space to guide and motivate users to seek professional help were least endorsed, which may be discussed in the light of findings that distressed, non-treatment-seeking youth prefer informal sources of support due to the previously mentioned barriers. It may partly be explained by the normalization of distress and not wanting or knowing how to label problems as distress due to poor mental health literacy.11,18

Many of the study’s youth respondents stressed the need for OMHPSFs to go beyond the deficit model and cater to the mental health promotion needs of young people. Studies show that approaches to managing distress alone may not necessarily result in improved well-being; distress and well-being indicators must be considered. 57 Youth in the study perceived OMHPSFs as useful in providing a sense of relatedness, belongingness, varied perspectives on relevant matters, and a means to solve problems vicariously—all congruent with findings from published OMHPSF studies.28,30–33

Youth Inclination to Seek and Provide Help on OMHPSFs

In this study, the high utility and inclination to use OMHPSFs were disproportionate to the low number of respondents who have previously visited or posted on such platforms. This may be due to the little traction that mental health forums have gained in India. 25 However, recent estimates suggest that Indians, by ethnicity, constitute the third largest user base on Reddit, and 15% of Quora users are Indian nationals. 58 But no such estimates are available for online mental health forums. Another reason may be that despite the existence and awareness of such forums, they may not be appealing enough to capture the interests of the young masses, 34 which connects to the findings related to design features of OMHPSFs to enhance aesthetic appeal and ease of use, which thereby promote their popularity and youth inclination to use OMHPSFs. Finally, perceived peer norms 51 may strongly influence youth activity on OMHPSFs, which are catalysts for destigmatizing mental illness and help-seeking; these findings may further be extended to OMHPSF design and popularization.

Findings in the study importantly revealed that youth with higher levels of distress were more inclined to use OMHPSFs to seek support from their peers. This result may be dissected from the perspective of the help-seeking paradox documented in literature59,60—those who are highly distressed or those with diagnosable mental illnesses are less likely to seek professional help. This may explain why sampled youth experiencing high distress may be inclined toward seeking help from an informal source of support, such as OMHPSFs, instead of a mental health professional—also linked to the previously mentioned help-seeking barriers of distressed young adults.9–15

On a related note, the least endorsed function of OMHPSFs in scope is to provide guidance and motivation to get professional help. This offers an opportunity to facilitate professional help-seeking through motivation enhancement and “nudges”; nudge theory 61 promotes practice and policy that alters the environment to encourage health-enhancing behavior instead of campaigns that directly target behavior through increased knowledge and improved decision-making related to healthy behaviors. Hence, nudges, as the name suggests, involve subtly modifying environments of framing information to propel users to engage in healthy behaviors such as seeking professional support.62,63 Although using nudge theory to encourage healthy behavior change is a promising strategy, the available evidence is currently insufficient for OMHPSFs.

The Role of MHP&Cs on OMHPSFs

Findings from the study on the integral function of qualified MHP&Cs in training, supervision, and moderation of OMHPSFs align with a large evidence base that necessitates their involvement in running online mental health forums to ensure the safety of users and the credibility of content posted.64–68 However, existing studies only amplify the views of lay moderators on general forums; very few have gauged the perspectives of online forum moderators who are qualified mental health professionals, as in the present study.

Suggested Design Features of OMHPSFs: Anonymity and Aesthetic Appeal

Youth respondents and interviewees listed numerous design features of OMHPSFs to enhance perceived utility and inclination to use them, which emerged as themes of anonymity, appeal, ease of use, and accessibility. Several studies69–72 revealed a strong positive correlation between anonymity and self-disclosure, conceptualized as a form of “benign self-disinhibition.” 72 Allowing online anonymity has shown promise in combating the “spiral of silence,” 70 that is, the apprehensiveness of young online participants to share their views and concerns. Noponen 73 identified nine key visually pleasing features of online platforms that can enhance user engagement—“simplicity, diversity, colorfulness, craftsmanship, unity, complexity, intensity, novelty, and interactivity”—which agree with suggestions provided by respondents in the present study. In another relevant study on OMHPSFs, the perceived utility was positively correlated to visual appeal, irrespective of whether the website was high or low on usability. 74

Suggested Strategies to Popularize OMHPSFs Among Indian Youth

Suggestions for popularizing OMHPSFs included word-of-mouth (WOM), collaborations with social media influencers, and spreading awareness in educational institutions, which may be discussed in the light of social marketing strategies. Social marketing has shown promising outcomes in behavior change research on identifying barriers to help-seeking, destigmatizing mental illness, and sprouting channels for support-seeking75,76—not yet explored with specific consideration of OMHPSFs.

Youth spreading the word about positive experiences on online platforms is documented to be a powerful tool to popularize any SNS.77–79 Aesthetic appeal and ease of use have been deemed essential for WOM strategies to be effective. Although ethical considerations of being a “mental health influencer” are in the process of being teased out in research and practice,80,81 utilizing social media influencers’ powerful online presence may prove to be an efficient strategy to popularize OMHPSFs. Community-level mental health promotion initiatives in colleges and workplaces, where OMHPSFs may be presented as one avenue to destigmatize mental health, may be pivotal in improving mental health literacy among emerging adults and promoting help-seeking.82–84

Supplementary analysis revealed that youth who had previously visited and engaged in online support forums were more likely to seek help on OMHPSFs. Studies on mental health help-seeking in developing nations substantiate this, highlighting the importance of familiarity and prior exposure to mental health services in encouraging young persons to seek appropriate support.85–87 This has essential implications for popularizing OMHPSFs among young people.

Study Limitations

Limitations of the study are as follows: the generalizability of findings is limited to urban, English-speaking educated youth. Findings may only be treated as partially conclusive due to a small sample size, non-probability sampling, and potential self-selection bias in the survey phase. Although selecting the youth subsample with prior engagement on similar forums was deliberate, the perspectives of those with low inclination were missed. Certain relevant areas—such as reasons for non-use despite high inclination—could not be explored comprehensively in the survey to optimize survey length and minimize respondent burden.

Future Implications

Preliminary findings from this exploratory study may nevertheless provide impetus to future research in this fast-growing domain of digital mental health with larger, more representative youth samples, more diverse stakeholder groups, and research comparing youth who use online mental health forums with those who do not on relevant mental health and help-seeking parameters. Study findings may be utilized to inform the operators of existing OMHPSFs to enhance appeal, safe use, popularity, utility, and credibility.

Conclusion

Sampled youth in the present study indicated a high inclination to use OMHPSFs to seek and provide mental health support. There was a modest relationship between psychological distress as measured on K10 and youth inclination to seek help on OMHPSFs. Most respondents defined the scope of OMHPSFs as a space for emotional and informational support from those of similar age to deal with relevant stressors and issues. Respondents indicated that OMHPSFs would be highly useful in vicariously learning ways to address daily life challenges, gain a fresh perspective, and provide a sense of relatedness and belongingness. Youth and MHP&Cs emphasized the importance of anonymity, visual appeal, ease of navigation, and accessibility in improving youth inclination toward OMHPSFs. The MHP&Cs highlighted the role of qualified mental health professionals in the moderation, training, and supervision of OMHPSFs.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from The Institutional Ethical Committee–Behavioral Sciences Division at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bengaluru, India [Reference No: NIMH/DO/BEH. Sc. Div./2021–22].

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent: All participants in the survey and interview phases consented to study participation.

References

- 1.UN DESA. International youth day— ten key messages. Population division of the United Nations department of economic and social affairs, https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2019/08/WYP2019_10-Key-Messages_GZ_8AUG19.pdf (12 August 2019).

- 2.Central Statistics Office. Youth in India. Ministry of statistics and program implementation, https://mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Youth_in_India_2022.pdf (2022).

- 3.Chandrasekhar CP, Ghosh J and Roychowdhury A.. The ‘demographic dividend’ and young India’s economic future. Econ Polit Wkly, 2006. Dec 9:(41) 5055–5064. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunitha S and Gururaj G.. Health behaviors & problems among young people in India: cause for concern & call for action. Indian J Med Res, 2014; 140(2): 185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal VN, et al. National mental health survey of India, 2015–16: prevalence, patterns and outcomes. Bengaluru: national Institute of mental health and neuro sciences. Bengaluru: NIMHANS Publication, 2016, p.129. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg K, Kumar CN and Chandra PS. Number of psychiatrists in India: baby steps forward, but a long way to go. Indian J Psychiatry, 2019; 61(1): 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautham MS, Gururaj G, Varghese M, et al. The national mental health survey of India (2016): prevalence, socio-demographic correlates and treatment gap of mental morbidity. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2020. Jun; 66(4): 361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desiraju K. Union budget for mental health 2023–2024: an analysis. Report, Indian Mental Health Repository, India, February 2023.

- 9.Johnson JA, Devdutt J, Mehrotra S, et al. Barriers to professional help-seeking for distress and potential utility of a mental health APP components: stakeholder perspectives. Cureus, 2020; 12(2): e7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shidhaye R and Kermode M.. Stigma and discrimination as a barrier to mental health service utilization in India. Int Health, 2013; 5(1): 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fathima MA, Mehrotra S and Sudhir PM. Depression with and without preceding life event: differential recognition and professional help-seeking inclination in youth? Indian J Soc Psychiatry, 2018; 34(2): 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathur GS, Ann SG, Kumar R, et al. Enhancing mental health literacy in India to reduce stigma: the fountainhead to improve help-seeking behavior. J Public Ment Health, 2014. Sep 9; 13(3): 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thippeswamy H, Desai G and Chandra P. Help-seeking patterns in women with postpartum severe mental illness: a report from southern India. Arch Women Ment Health, 2018; 21: 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal HR, Yadav S, Joy PS, et al. Treatment non-seeking in alcohol users: a community-based study from North India. J Stud Alcohol, 2003; 64(5): 631–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehrotra S. Barriers and enablers of professional help-seeking for common mental health concerns: perspectives of distressed non-treatment seeking young adults. Online J Health Allied Sci, 2022; 21(2): 9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhugra D, Tasman A, Pathare S, et al. The WPA-lancet psychiatry commission on the future of psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry, 2017. Oct 1; 4(10): 775–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanghvi PB and Mehrotra S. Help-seeking for mental health concerns: a review of Indian research and emergent insights. J Health Res, 2021. March 10; 36(3): 428–441. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM and Christensen H.. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 2010. Dec; 10(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pretorius C, Chambers D and Coyle D.. Young people’s online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: a systematic narrative review. J Med Internet Res, 2019. Nov 19; 21(11): e13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali K, Farrer L, Gulliver A, et al. Online peer-to-peer support for young people with mental health problems: a systematic review. JMIR Ment Health, 2015. May 19; 2(2): e4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Choudhury M and De S.. Mental health discourse on Reddit: self-disclosure, social support, and anonymity. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media. 2014. Jun 1–4; Michigan, USA, 2014. p. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lerman BI, Lewis SP, Lumley M, et al. Teen depression groups on Facebook: a content analysis. J Adolesc Res, 2017. Nov; 32(6): 719–741. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumel A, Tinkelman A, Mathur N, et al. Digital peer-support platform (7cups) as an adjunct treatment for women with postpartum depression: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 2018. Feb 13; 6(2): e9482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prescott J, Hanley T and Ujhelyi K.. Peer communication in online mental health forums for young people: directional and nondirectional support. JMIR Ment Health, 2017. Aug 2; 4(3): e6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feerst E and Stewart D.. What is an Internet forum? Videojug on YouTube. https://web.archive.org/web/20081011092536/http://www.videojug.com/expertanswer/internet-communities-and-forums-2/what-is-an-internet-forum (2008, accessed July 15, 2022).

- 26.McCosker A. Engaging mental health online: insights from beyondblue’s forum influencers. New Media Soc, 2018. Dec; 20(12): 4748–4764. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Merry J, Goggin G, Campbell A, et al. Social connection and online engagement: insights from interviews with users of a mental health online forum. JMIR Ment Health, 2019. Mar 26; 6(3): e11084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendal S, Kirk S, Elvey R, et al. How a moderated online discussion forum facilitates support for young people with eating disorders. Health Expect, 2017. Feb; 20(1): 98–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banwell E, Hanley T, De Ossorno Garcia S, et al. The Helpfulness of web-based mental health and well-being forums for providing peer support for young people: cross-sectional exploration. JMIR Form Res, 2022. September 9; 6(9): e36432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens M, Cartagena Farías J, Mindel C, et al. Pilot evaluation to assess the effectiveness of youth peer community support via the Kooth online mental wellbeing website. BMC Public Health, 2022. Oct 12; 22(1): 1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kummervold PE, Gammon D, Bergvik S, et al. Social support in a wired world: use of online mental health forums in Norway. Nord J Psychiatry. 2002. Jan 1; 56(1): 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanley T, Prescott J and Gomez KU. A systematic review exploring how young people use online forums for support around mental health issues. J Ment Health Couns. 2019; 28(5): 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith-Merry J, Goggin G, Campbell A, et al. Social connection and online engagement: insights from interviews with users of a mental health online forum. JMIR Ment Health, 2019. Mar 26; 6(3): e11084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webb M, Burns J and Collin P.. Providing online support for young people with mental health difficulties: challenges and opportunities explored. Early Interv. Psychiatry, 2008. May; 2(2): 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng D, Rogers T and Naslund JA. The role of moderators in facilitating and encouraging peer-to-peer support in an online mental health community: a qualitative exploratory study. J Tech Behav Science, 2023. Jun; 8(2): 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha M, Kataria K, Mehrotra S, et al. Online peer support forum for youth mental health. In: Manodarpan- integrated approach to mental health and well-being in the universities: perspectives, methodologies, and practices- national conference by the ministry of education and Maitreyi college. New Delhi: Delhi University, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murugiah P. Internet usage in India: the global analytics. In: Measuring and implementing altmetrics in library and information science research. 1st ed. IGI Global, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thayer SE and Ray S.. Online communication preferences across age, gender, and duration of internet use. Cyberpsychol Behav, 2006. Aug 1; 9(4): 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2003. Feb 1; 60(2): 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrews G and Slade T.. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Zeal J Public Health, 2001. Dec 1; 25(6): 494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duggal C and Bagasrawala L.. Adolescent and youth mental health in India: status and needs. In: Bharat S and Sethi G (eds) Health and wellbeing of India’s young people: challenges and prospects. Singapore: Springer, 2019, pp.51–83. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaisoorya TS, Desai G, Beena KV, et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in adolescent students from India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry, 2017. Jun; 27(2): 56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao AS. Academic stress and adolescent distress: the experiences of 12th standard students in Chennai, India [dissertation]. Tucson: The University of Arizona, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy KJ, Menon KR and Thattil A.. Academic stress and its sources among university students. Biomed Pharmacol J, 2018. March 25; 11(1): 531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhargava D and Trivedi H.. A study of causes of stress and stress management among youth. IRA-Int J Manag Soc Sci, 2018. Jul 18; 11(03): 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar S, Mohanraj R, Lidiya A, et al. Exploring perspectives on mental well-being of urban youth from a city in South India. World Soc Psychiatry, 2021. May 1; 3(2): 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sahoo S and Khess CR. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among young male adults in India: a dimensional and categorical diagnoses-based study. J Nerv Ment Dis, 2010. December 1; 198(12): 901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhujade VM. Depression, anxiety and academic stress among college students: a brief review. Indian J Health Wellbeing, 2017. Jul 1; 8(7): 748–751. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhattacharya A. Challenges to mental well-being, perceived resources, and felt needs during COVID-19 among college youth in India. Online J Health Allied Sci, 2022. April 30; 21(1): 4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tracy EM and Biegel DE. Preparing social workers for social network interventions in mental health practice. J Teach Soc Work, 1994. Nov 4; 10(1–2): 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fathima MA, Mehrotra S and Sudhir P.. Perceived peer norms and help-seeking for depression in Indian college youth. Int J Med Public Health, 2020; 10(4): 152–154. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhola P, Rekha DP, Sathyanarayanan V, et al. Self-reported suicidality and its predictors among adolescents from a pre-university college in Bangalore, India. Asian J Psychiatr, 2014. February 1; 7: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehrotra S and Tripathi R.. Recent developments in the use of smartphone interventions for mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2018. Sep 1; 31(5): 379–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haavik L, Joa I, Hatloy K, et al. Help seeking for mental health problems in an adolescent population: the effect of gender. J Ment Health, 2017. July 18; 28(5):467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaves A, Arnáez S, Castilla D, et al. Enhancing mental health literacy in obsessive-compulsive disorder and reducing stigma via smartphone: a randomized controlled trial protocol. Internet Interv, 2022. September 1; 29: 100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chanda P, Wagh A, Johnson JA, et al. MINDNOTES: a mobile platform to enable users to break stigma around mental health and connect with therapists. In: Conference on computer supported cooperative work and social computing. 2021. Oct 23–27; virtual; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehrotra S and Swami N.. Looking beyond distress: a call for spanning the continuum of mental health care. Cureus, 2018. Jun 15; 10(6): e2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Statista. Number of social network users in India from 2015 to 2020, with estimates until 2040, https://www.statista.com/statistics/278407/number-of-social-network-users-in-india/ (February 2024).

- 59.Deane FP, Wilson CJ and Ciarrochi J.. Suicidal ideation and help-negation: not just hopelessness or prior help. J Clin Psychol, 2001. Jul; 57(7): 901–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson CJ. General psychological distress symptoms and help-avoidance in young Australians. Adv Ment Health, 2010. August 1; 9(1): 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thaler R and Sunstein C. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. 1st ed. Connecticut: Yale University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halsall T, Garinger C, Dixon K, et al. Evaluation of a social media strategy to promote mental health literacy and help-seeking in youth. J Consum Health Internet, 2019. Jan 2; 23(1): 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrison JD and Patel MS. Designing nudges for success in health care. AMA J Ethics, 2020. Sep 1; 22(9): 796–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Owens C, Sharkey S, Smithson J, et al. Building an online community to promote communication and collaborative learning between health professionals and young people who self-harm: an exploratory study. Health Expect, 2015. Feb; 18(1): 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hanley T, Prescott J and Gomez KU. A systematic review exploring how young people use online forums for support around mental health issues. J Ment Health, 2019. Sep 3; 28(5): 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reddy PS, Keerthika V, Prasad KS, et al. Monitoring suspicious discussion on online forum. In Diaz VG and Aponte GJR (ed): Confidential computing: hardware-based memory protection. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 23 September 2022, pp.47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perowne R and Gutman LM. Barriers and enablers to the moderation of self-harm content for a young person’s online forum. J Ment Health, 2022. May 10: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lekka F, Efstathiou G and Kalantzi-Azizi A. The effect of counseling-based training on online peer support. Br J Guid Couns, 2015. Jan 1; 43(1): 156–170. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freeman M and Bamford A.. Student choice of anonymity for learner identity in online learning discussion forums. Int J E-Learn, 2004; 3(3): 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woong Yun G and Park SY. Selective posting: willingness to post a message online. J. Comput-Mediat Comm, 2011. January 1; 16(2): 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mann S and Carter MC. Emotional disclosures and reciprocal support: the effect of account type and anonymity on supportive communication over the largest parenting forum on Reddit. Hum Behav Emerg Technol, 2021. Dec; 3(5): 668–676. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clark-Gordon CV, Bowman ND, Goodboy AK, et al. Anonymity and online self-disclosure: a meta-analysis. Commun Rep, 2019. May 4; 32(2): 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Noponen S. What makes a beautiful website? factors influencing perceived website aesthetics. PhD Thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Phillips C and Chaparro B.. Visual appeal vs. usability: which one influences user perceptions of a website more? Usability News, 2009. Oct 15; 11(2): 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deshpande S and Lee NR. Social marketing in India. 1st ed. Delhi: Sage Publications, 30 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Collins RL, Wong EC, Breslau J, et al. Social marketing of mental health treatment: California’s mental illness stigma reduction campaign. Am J Public Health, 2019. June; 109(S3): S228–S235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okazaki S. Determinant factors of mobile-based word-of-mouth campaign referral among Japanese adolescents. Psychol Mark, 2008. Aug; 25(8): 714–731. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kozinets RV, De Valck K, Wojnicki AC, et al. Networked narratives: understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. J Mark, 2010. Mar; 74(2): 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen Z and Yuan M.. Psychology of word of mouth marketing. Curr Opin Psychol, 2020. Feb 1; 31: 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.White E and Hanley T.. Therapist + social media = mental health influencer? Considering the research focusing upon key ethical issues around the use of social media by therapists. Couns Psychother Res, 2023. Mar; 23(1): 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Triplett NT, Kingzette A, Slivinski L, et al. Ethics for mental health influencers: MFTs as public social media personalities. Contemp Fam Ther, 2022. Jun; 44(2): 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miller DN, Gilman R and Martens MP. Wellness promotion in the schools: enhancing students’ mental and physical health. Psychol Schools, 2008. Jan; 45(1): 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lattie EG, Nicholas J, Knapp AA, et al. Opportunities for and tensions surrounding the use of technology-enabled mental health services in community mental health care. Adm Policy Ment Health, 2020. Jan 47: 138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wasil AR, Malhotra T, Nandakumar N, et al. Improving mental health on college campuses: perspectives of Indian college students. Behav Ther, 2022. Mar 1; 53(2): 348–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang H. Help-seeking for stressful events among Chinese college students in Taiwan: roles of gender, prior history of counseling, and help-seeking attitudes. J Coll Stud Dev, 2008; 49(1): 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Çebi E. University students’ attitudes toward seeking psychological help: effects of perceived social support, psychological distress, prior help-seeking experience, and gender. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aloud N and Rathur A.. Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab Muslim populations. J Muslim Ment Health, 2009. Oct 30; 4(2): 79–103. [Google Scholar]