Abstract

BACKGROUND

Tourette syndrome (TS) is recognized as a neurodevelopmental disorder profoundly influenced by familial factors, particularly family functioning. However, the relationship among family functioning, tic severity, and quality of life in individuals with TS during childhood and adolescence remains unclear. We hypothesized that family functioning plays a role in the association between the severity of TS and quality of life in children.

AIM

To determine the role of family functioning in the relationship between TS severity and quality of life.

METHODS

This study enrolled 139 children (male/female = 113/26) with TS. We assessed tic severity using the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, quality of life via the Tourette Syndrome Quality of Life Scale, and family functioning through the Family Assessment Device. Our analysis focused on correlating these measures and exploring the mediating role of family functioning in the relationship between tic severity and quality of life. Additionally, we examined if this mediating effect varied by gender or the presence of comorbidity.

RESULTS

We found that family communication dysfunction had a significant mediating effect between tic severity and both psychological symptoms (indirect effect: Β = 0.0038, 95% confidence interval: 0.0006-0.0082) as well as physical and activities of daily living impairment (indirect effect: Β = 0.0029, 95% confidence interval: 0.0004-0.0065). For vocal tic severity, this mediation was found to be even more pronounced. Additionally, in male participants and those without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the mediating effect of family communication dysfunction was still evident.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the impact of family functioning on the tic severity and the quality of life in children. This relationship is influenced by gender and comorbid conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Keywords: Tourette syndrome, Family functioning, Quality of life, Tic severity, Children and adolescents

Core Tip: This was a retrospective study using a mediating effect model designed to investigate the role of family functioning in the relationship between Tourette syndrome severity and quality of life in children. The abnormal family communication function significantly mediated the relationship between the severity of Tourette syndrome and the quality of life of children. The effect was different between boys and girls and between children with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder in children and adolescents[1] characterized by the presence of multiple motor tics and at least one vocal tic. These symptoms persist for more than a year and typically manifest before 18 years of age, with the initial onset commonly occurring between ages 4 and 6 years[2]. The prevalence of TS is 0.3% to 0.9%[3-5] and is approximately three to four times higher in men than in women[6-8]. Notably, TS frequently co-occurs with other mental disorders, most commonly attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), affecting 55%-60% of TS cases[9]. Individuals with severe TS, especially when accompanied by comorbidities[10], exhibit functional impairment in daily life, such as in situations of learning[11], social interaction[12], entertainment[4], and family[4], thereby diminishing the quality of life for affected children[3,4,13,14]. With increasing tic severity, functional impairment increases[13].

Accumulating evidence underscores the influence of the family environment on TS, with factors such as changes in caregivers[15], shifts in family structure[16], and poor parenting styles[17,18]. The hostile couple relationship and nuclear family structure could increase the incidence of TS, especially in boys[16]. In particular, the internal quality of the family (i.e., family functioning) may be a more critical factor affecting the mental health of family members[19], which has been verified in a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder[20,21], pervasive developmental disorders[20], ADHD[22,23], and TS[17,24]. The basic function of the family is to provide certain basic conditions for the healthy development of family members in physical, psychological, and social aspects[25]. Family functioning, which is the ability of the family system to complete a series of tasks (such as solving daily problems, coping with family emergencies, and adapting and promoting the development of the family and its members), is the core of the operation process of the family system. A study by Vermilion et al[17] revealed that youths with tic disorders experience lower quality of life and poorer family functioning than their peers without these conditions. The more severe the tics are, the more pronounced the negative impact on family functioning[24]. In addition, adverse family functioning is linked to behavioral problems in children with TS[26,27]. In research exploring TS comorbidity and family functioning, ADHD co-occurrence was linked to increased parenting stress[28]. Despite these insights, the intricate interplay among family functioning, tic severity, and quality of life in TS patients during critical developmental stages of childhood and adolescence remains insufficiently explored.

To address these issues, we employed 139 children aged 6-18 years from the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at Beijing Children’s Hospital. We used the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) to assess the severity of TS, the Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Quality of Life Scale (GTS-QoL) to assess the quality of life of children with TS, and the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) to assess family functioning. We propose the following hypotheses: (1) Tic severity and the quality of life of TS children are related to family functioning; (2) Family dysfunction mediates the association between tic severity and quality of life in children with TS; and (3) The mediating effect of family functioning is affected by sex and the presence of ADHD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

We recruited 154 participants from the outpatient department of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University from May 1, 2022 to October 1, 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Aged between 6 and 18 years; (2) Diagnosed with TS according to DSM-V criteria, with possible comorbidity of ADHD or obsessive compulsive disorder; (3) Normal intellectual functioning for questionnaire completion; and (4) Absence of physical disabilities. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) History or current comorbidity of childhood schizophrenia, mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder, or intellectual disability; (2) History or current comorbidity of neurological disorders such as epilepsy or traumatic brain injury; (3) History or current comorbidity of other severe physical illnesses; and (4) Inability to complete assessments. We ultimately included a total of 139 individuals (male/female = 113/26) aged 6-18 years (mean ± SD = 10.3 ± 2.3).

Assessments

Evaluation of tic severity: In our study, we used the Chinese version of the YGTSS as a tool to assess tic severity[29-31]. The YGTSS is a scale evaluated by clinical doctors, and is commonly used to assess tic severity in children and adolescents. The YGTSS includes multiple tic symptoms, which can be divided into four categories: Simple vocalizations, complex vocalizations, simple motor movements, and complex motor movements. It scores tics based on frequency, intensity, complexity, and interference with daily activities, providing separate scores for motor tics, vocal tics, and overall severity, each ranging up to 25, 25, and 50, respectively. Additionally, it independently assesses impairment caused by tics (0-50) and incorporates it into the total tic score. The Chinese version of the YGTSS has demonstrated robust reliability and validity[32], making it an appropriate tool for assessing tic disorders in the Chinese population.

Evaluation of quality of life: The GTS-QoL is a specific self-report questionnaire used to assess the quality of life of children and adolescents with TS[30,31] that indirectly reflects their functional impairment. The scale consists of 27 items, assessing the impact on the psychological, physical and activities of daily living, obsessive-compulsive behavior, and cognitive ability. A higher score indicates a poorer quality of life. Additionally, it features a visual analog scale, which measures life satisfaction in children with TS, with scores ranging from 0 (poorest state) to 100 (best state). The GTS-QoL has good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity[31,33,34].

Assessment of family functioning: The FAD is used to assess family functioning[35-37]. This self-administered screening questionnaire effectively identifies potential issues within the family system and objectively reflects the situation of family functioning. The scale consists of 60 items, divided into seven dimensions: Problem-solving, communication, role, effective responsiveness, effective involvement, behavioral control, and general functioning. The higher the score, the more evident the issues in that particular dimension. The FAD is well-established for its reliability and validity in assessing family functioning[36,38].

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to assess data normality. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous data are presented as the means ± SD or medians and interquartile ranges, depending on their distribution. Spearman correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship among tic severity, family functioning, and quality of life. First, bivariate correlation analysis was performed on the scores of the YGTSS, including the total score, motor tic score, and vocal tic score; the scores of the GTS-QoL, including psychological symptoms, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, physical and activities of daily living impairment, cognitive function impairment, and global life satisfaction; and the problem-solving, communication, role, effective responsiveness, effective involvement, behavior control and general functioning scores of the FAD. Second, the mediating effect of the family functioning score between the YGTSS score and the TS quality of life score was analyzed. The dimensions of the FAD that are were related to the total score of the YGTSS and either dimension of the GTS-QoL were extracted. The SPSS plug-in process macro program Model 4 was used for bootstrap sampling to test the mediating effect, and the sampling number was set to 5000. The significance was judged according to the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the parameters. Finally, we verified whether the mediating effect of family functioning still exists in children of different genders and with or without comorbid ADHD. The procedure was replicated to assess the variability of mediation effects by sex and the existence of comorbid ADHD. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.

RESULTS

Distribution of general information

A total of 154 subjects were recruited from the psychiatry clinic of Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 139 participants (113 males and 26 females) aged 6-17 years (mean ± SD = 10.3 ± 2.3) were included, with a male-to-female ratio of 4.3:1. The detailed demographic and general information of the study cohort is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of children with Tourette syndrome

|

Item

|

Total (n = 139)

|

Male (n = 113)

|

Female (n = 26)

|

With ADHD (n = 52)

|

Without ADHD (n = 87)

|

| Sex | |||||

| Male, n (%) | 113 (81.30) | - | - | 45 (86.50) | 68 (78.20) |

| Female, n (%) | 26 (18.70) | - | - | 7 (13.50) | 19 (21.80) |

| Age [M (P25, P75)] | 10 (9, 12) | 10 (9, 12) | 10 (9, 11) | 10 (9, 12) | 10 (9, 12) |

| YGTSS Score [M (P25, P75)] | |||||

| Total tic | 23 (16, 30) | 22 (16, 28) | 27 (17, 31) | 19 (12, 26) | 24 (18, 32) |

| Motor tic | 13 (10, 15) | 13 (10, 15) | 14 (10, 17) | 12 (9, 15) | 13 (11, 16) |

| Vocal tic | 7 (0, 11) | 7 (0, 11) | 8 (0, 11) | 6 (0, 9) | 8 (0, 11) |

| GTS-QoL Score [M (P25, P75)] | |||||

| Obsessive-compulsive | 0.40 (0.00, 0.80) | 0.40 (0.00, 0.70) | 0.40 (0.20, 0.80) | 0.20 (0.00, 0.60) | 0.40 (0.00, 0.80) |

| Psychological | 0.70 (0.30, 1.50) | 0.60 (0.30, 1.30) | 1.00 (0.60, 1.60) | 0.70 (0.40, 1.20) | 0.70 (0.20, 1.50) |

| Cognitive impact | 0.80 (0.30, 1.50) | 0.80 (0.30, 1.50) | 0.90 (0.50, 1.60) | 0.90 (0.80, 1.80) | 0.80 (0.30, 1.50) |

| Physical and activities of daily living | 0.40 (0.10, 0.90) | 0.40 (0.10, 0.80) | 0.50 (0.10, 1.00) | 0.40 (0.10, 0.70) | 0.40 (0.10, 1.00) |

| Visual analogue scale | 80 (60, 100) | 80 (60, 100) | 80 (60, 80) | 80 (60, 100) | 80 (60, 100) |

| FAD Score [M (P25, P75)] | |||||

| General functioning | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) | 2.00 (1.80, 2.40) | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) | 2.20 (1.90, 2.40) | 2.00 (1.70, 2.30) |

| Problem-solving | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) | 2.00 (1.80, 2.30) |

| Communication | 2.30 (2.00, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.00, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.10, 2.70) | 2.30 (1.90, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.00, 2.60) |

| Roles | 2.20 (2.00, 2.50) | 2.20 (2.00, 2.50) | 2.20 (1.90, 2.40) | 2.20 (2.00, 2.50) | 2.20 (1.90, 2.50) |

| Effective responsiveness | 2.30 (2.00, 2.50) | 2.30 (2.00, 2.50) | 2.20 (1.80, 2.50) | 2.30 (2.20, 2.70) | 2.20 (1.80, 2.50) |

| Effective involvement | 2.30 (2.10, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.10, 2.60) | 2.40 (2.00, 2.70) | 2.40 (2.30, 2.70) | 2.30 (2.00, 2.60) |

| Behavior control | 2.30 (2.10, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.10, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.00, 2.40) | 2.30 (2.10, 2.60) | 2.30 (2.10, 2.40) |

ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; GTS-QoL: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-quality of Life Scale; FAD: Family Assessment Device.

Correlations among tic severity, family functioning, and quality of life

We first explored the relationship between tic severity and family functioning. We found that overall tic severity was significantly positively correlated with general dysfunction, communication dysfunction, and effective responsiveness dysfunction, as identified by the FAD (all P < 0.01). Furthermore, the severity of vocal tics was notably associated with abnormalities in communication functioning (P < 0.01) and effective responsiveness (P < 0.05) within the FAD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations among tic severity, family functioning, and quality of life

|

r

|

YGTSS-total tic

|

YGTSS-motor tic

|

YGTSS-vocal tic

|

FAD-general functioning

|

FAD-problem-solving

|

FAD-communication

|

FAD-roles

|

FAD-effective responsiveness

|

FAD-effective involvement

|

FAD-behavior control

|

GTS-QoL-obsessive-compulsive

|

GTS-QoL-psychological

|

GTS-QoL-cognitive impact

|

GTS-QoL-physical and ADL

|

GTS-QoL-visual analogue scale

|

| YGTSS-total tic | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| YGTSS-motor tic | 0.58b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| YGTSS-vocal tic | 0.70b | 0.25b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-general functioning | 0.25b | 0.08 | 0.16 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-problem-solving | 0.07 | -0.02 | 0.15 | 0.50b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-communication | 0.30b | 0.14 | 0.28b | 0.68b | 0.36b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-roles | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.70b | 0.29b | 0.61b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-effective responsiveness | 0.27b | 0.12 | 0.18a | 0.72b | 0.38b | 0.70b | 0.64b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-effective involvement | 0.05 | 0.01 | -0.03 | 0.50b | 0.01 | 0.39b | 0.52b | 0.47b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FAD-behavior control | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.38b | 0.14 | 0.26b | 0.36b | 0.42b | 0.32b | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| GTS-QoL-obsessive-compulsive | 0.27b | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.18a | 0.16 | 0.24b | 0.08 | 0.14 | -0.02 | 0.03 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| GTS-QoL-psychological | 0.30b | 0.11 | 0.21a | 0.32b | 0.26b | 0.30b | 0.15 | 0.20a | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.64b | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| GTS-QoL-cognitive impact | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.20a | 0.10 | 0.20a | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.54b | 0.66b | 1.00 | - | - |

| GTS-QoL-physical and ADL | 0.34b | 0.21a | 0.25b | 0.22a | 0.08 | 0.31b | 0.20a | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.63b | 0.69b | 0.52b | 1.00 | - |

| GTS-QoL-visual analogue scale | -0.15 | -0.09 | -0.07 | -0.26b | -0.14 | -0.26b | -0.18a | -0.16 | -0.09 | -0.04 | -0.35b | -0.50b | -0.36b | -0.37b | 1.00 |

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; FAD: Family Assessment Device; GTS-QoL: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-quality of life Scale; ADL: Activities of daily living.

We subsequently examined the link between tic severity and quality of life in children with TS. Our results revealed a significant positive correlation between overall tic severity and the presence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, psychological symptoms, physical and activities of daily living impairments, as measured by the GTS-QoL (all P < 0.01). Specifically, motor tic severity was correlated with physical and activities of daily living impairments (P < 0.05). Additionally, vocal tic severity was positively correlated with psychological symptoms (P < 0.05), physical and activities of daily living impairments (P < 0.01) (Table 2).

Finally, we investigated the relationships between various aspects of family functioning and quality of life. We found that obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the GTS-QoL were positively correlated with general dysfunction (P < 0.05) and communication dysfunction (P < 0.01) in the FAD. Psychological symptoms in the GTS-QoL were positively correlated with general dysfunction, problem-solving dysfunction, communication dysfunction, and effective responsiveness dysfunction in the FAD (all P < 0.05), with general dysfunction exhibiting the strongest association. Furthermore, cognitive impairment in the GTS-QoL was also positively correlated with general dysfunction and communication dysfunction in the FAD (all P < 0.05). Physical and activities of daily living impairments, as assessed by the GTS-QoL, correlated positively with general dysfunction, communication dysfunction, and role dysfunction (all P < 0.05). The visual analog scale (reflection of life satisfaction) scores on the GTS-QoL were negatively correlated with general dysfunction, communication dysfunction, and role dysfunction scores on the FAD (all P < 0.05) (Table 2).

The mediating role of family functioning in the relationship between tic severity and quality of life

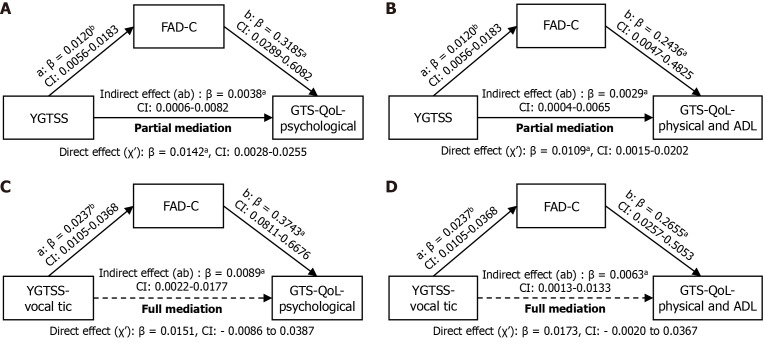

To investigate the mediating role of family functioning in the relationship between tic severity and quality of life in children with TS, a mediation analysis was performed. We considered tic severity as the independent variable, family communication functioning as the mediator, and quality of life as the dependent variable. The analysis revealed that family communication partially mediated the relationship between total tic severity and both psychological symptoms (indirect effect: Β = 0.0038, 95%CI: 0.0006-0.0082; Figure 1A) and physical and activities of daily living impairment (indirect effect: Β = 0.0029, 95%CI: 0.0004-0.0065; Figure 1B). In contrast, it fully mediated the relationship between vocal tic severity and both psychological symptoms (indirect effect: Β = 0.0089, 95%CI: 0.0022-0.0177; Figure 1C) and physical and activities of daily living impairment (indirect effect: Β = 0.0063, 95%CI: 0.0013-0.0133; Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

The mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between tic severity and quality of life. A: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between total tic severity and psychological symptoms; B: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between total tic severity and physical and activities of daily living impairments; C: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between vocal tic severity and psychological symptoms; D: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between vocal tic severity and physical and activities of daily living impairment. CI: Confidence interval; GTS-QoL: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Quality of Life Scale; YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; FAD: Family Assessment Device; C: Communication; ADL: Activities of daily living. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01.

Validation of sex and comorbidity on the mediation model

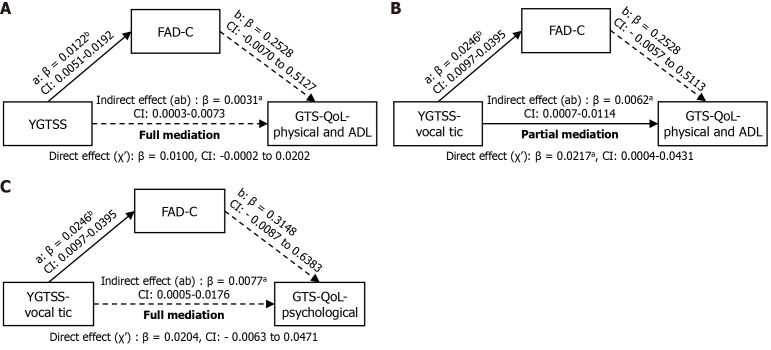

To verify gender differences in the mediating effects, our study revealed that the mediating effect of family communication functioning between total tic severity and physical and ADL impairments persisted in males, indicating complete mediation (indirect effect: Β = 0.0031, 95%CI: 0.0003-0.0073; Figure 2A). However, these mediating effects were not observed in females (indirect effect: Β = 0.0002, 95%CI: -0.0080 to 0.0076). In addition, the full mediating effect of family communication between vocal tic severity and both physical and activities of daily living impairments (indirect effect: Β = 0.0062, 95%CI: 0.0007-0.0114; Figure 2B) and psychological symptoms (indirect effect: Β = 0.0077, 95%CI: 0.0005-0.0176; Figure 2C) was also observed in males but not in females. These findings suggest a gender-specific influence of family functioning on the mediation effect.

Figure 2.

The mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between tic severity and quality of life in males. A: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between total tic severity and physical and activities of daily living impairments; B: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between vocal tic severity and physical and activities of daily living impairments; C: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between vocal tic severity and psychological symptoms. CI: Confidence interval; GTS-QoL: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Quality of Life Scale; YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; FAD: Family Assessment Device; C: Communication; ADL: Activities of daily living. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01.

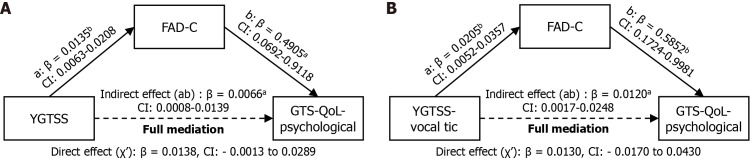

To ascertain the impact of comorbid ADHD on the mediation effect, we found that in the subset of children without ADHD, family communication fully mediated the relationship between tic severity and psychological symptoms (indirect effect: Β = 0.0066, 95%CI: 0.0008-0.0139; Figure 3A). This mediating effect was also observed for vocal tic severity and psychological symptoms (indirect effect: Β = 0.0120, 95%CI: 0.0017-0.0248; Figure 3B). However, no mediating effect of family functioning was observed in children with comorbid ADHD. These results indicate that the mediating role of family functioning is contingent upon the presence or absence of ADHD.

Figure 3.

The mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between tic severity and quality of life in children without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between total tic severity and psychological symptoms; B: Mediating effect of family functioning on the relationship between vocal tic severity and psychological symptoms. CI: Confidence interval; GTS-QoL: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Quality of Life Scale; YGTSS: Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; FAD: Family Assessment Device; C: Communication; ADL: Activities of daily living. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that family functioning, particularly in terms of family communication, plays a mediating role in the relationship between tic severity and quality of life in children with TS. Specifically, family communication dysfunction was found to be positively associated with overall tic severity, vocal tic severity, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, psychological symptoms, physical and activities of daily living impairments, and cognitive impairment in children with TS. Importantly, the mediating effect of family communication was consistent between male children with TS and those without ADHD. The findings highlight the importance of evaluating family functioning to understand the quality of life of children with TS and provide new evidence for clinical interventions aimed at improving family communication and overall functioning.

Our results are consistent with previous findings that the severity of TS is associated with worse quality of life in children, as severe tics adversely affect daily activities, learning, and social interaction[13,39,40]. The severity of TS is positively correlated with psychological symptoms, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and physical and activities of daily living impairment. This aligns with Cavanna et al[41] and other large-scale studies[42], indicating that higher tic severity predicts worse quality of life and poorer outcomes across various functional domains, including the home. Children with severe tics may suffer from more discrimination and rejection, multiple pressures, and more attention, which may have a certain impact on their psychology and are prone to emotional and cognitive problems. Children with severe motor tics may have more self-injury, causing damage to the body, and may also have an impact on the motor functioning of children because of limb tics. Families of children with severe tics may also experience greater parenting stress, which may affect the mental health of parents and the family environment. All of the above effects may contribute to poorer quality of life in children with severe TS, and our study puts more emphasis on the influence of family. However, contrasting findings by Huisman-van Dijk et al[43], Vermilion et al[17] and other studies[44] suggest that TS severity itself might not impact children’s quality of life, emphasizing the role of comorbidities such as ADHD. The complexity of comorbidities, sample sizes, and assessment tools could account for these differing findings.

Our findings indicate a correlation between TS severity and family functioning, which is influenced by factors such as family structure, relationships and atmosphere of family members, economic status, parenting styles, parental education and specific events encountered by the family. Notably, lower maternal education was associated with a greater risk of TS[11]. Abnormalities in total family functioning, communication functioning and emotional reaction functioning are positively correlated with the severity of TS. This aligns with previous studies showing that parents of children with TS have lower self-esteem[45], greater caregiver burden[46] (i.e., children with TS cause more adverse consequences for their caregivers), more family conflict, difficulty in family activities, lower quality of parent-child interaction, and more parental communication difficulties, which are related to the severity of TS[47]. Parents of children with more severe TS reported more difficulty caring for their children and more parenting frustrations[48]. In families with more children with severe TS, caregivers may experience more guilt and self-blame, greater parenting stress, and more incomprehension among their children and more family arguments. These conditions may explain the correlation between TS severity and family dysfunction. However, these findings contrast with those of Vermilion et al’s study[17], which reported better family functioning with greater tic severity, possibly due to differences in study populations and disease durations.

Our findings revealed a positive association between family dysfunction and decreased quality of life in children with TS. This aligns with results in existing literature, which has shown that the family environment is an important factor affecting the subjective quality of life of children with TS[40]. Conflicts and negative emotions within the family are related to poorer quality of life, whereas active participation in social and recreational activities are beneficial[40]. Children with TS have poor family interactions and poor quality of life in terms of family activities[40]. This finding is consistent with our research hypothesis. Our findings also support the potential of family-based behavioral therapy in improving quality of life[49,50]. This finding highlights the relationship between the family environment and quality of life in children with TS. Our study confirmed that general family dysfunction and communication dysfunction are related to obsessive-compulsive symptoms, psychological symptoms, cognitive impairment, and physical and activities of daily living impairment in children with TS. Although there are few studies on the relationship between family functioning and quality of life in TS, existing studies have shown that children with TS present more problems with their families and show more emotional problems[40]. This partially overlaps with the results of our study.

Our study demonstrated that family communication dysfunction partially mediated the relationship between TS severity and poorer quality of life in children with TS. Severe tics, especially vocal tics, indirectly reduce the quality of life of TS children by affecting family communication, mainly by causing more serious psychological symptoms and physical and activities of daily living impairment. Children with TS communicate less with adults in the family and witness more family arguments. Studies have reported that severe tics may have negative effects on social activities inside and outside the family, and behavioral problems and family stress caused by severe tics may lead to changes in parent-child communication styles[40]. Most studies have shown that TS is more common in males than in females and that ADHD is the most common comorbidity of TS[1,7,51-53]. Children with TS and ADHD have more domains of functional impairment[4] and worse quality of life[4,53] than those with TS alone. Notably, the mediating role of family communication functioning was present in boys and children without ADHD. Male sex and a lack of comorbid ADHD may be the driving factors of family communication functioning and may mediate tic severity and quality of life. These insights highlight the need for targeted attention to family functioning in clinical settings, especially for boys with vocal tic without ADHD. Early evaluation and intervention focusing on family functioning, coupled with home-based psychotherapy, could significantly reduce the impact of TS on children’s quality of life. In addition, a combination of home-based psychotherapy may be a good treatment option for these children.

Several considerations and avenues for future research emerge from this study. First, the modest sample size may limit the broad applicability of our findings. Particularly, when examining subgroups such as gender and comorbidities, the reduced sample size could diminish statistical power. Nonetheless, the gender ratio in our sample is consistent with that of prior research, lending it representativeness. Future studies could aim for larger, more diverse samples to enhance the statistical power and generalizability of the results. This could involve multi-site collaborations or leveraging existing large-scale datasets. Second, the reliance on single-center clinical-based sampling may affect the generalizability of our findings. To mitigate the risk of sample bias, future research could incorporate a multi-center approach, drawing from different geographic regions or demographic groups to better represent the broader population. Third, its cross-sectional design constrains our ability to draw causal links between TS severity, family functioning, and children’s quality of life. Longitudinal studies would provide a more nuanced understanding of how family functioning evolves over time. Finally, the current assessment of family functioning focuses primarily on the family environment. Future endeavors should extend this evaluation to encompass both the tangible (hard) and intangible (soft) aspects of the family environment.

CONCLUSION

Greater tic severity and abnormal family function in children with TS are associated with poor quality of life in children with TS. Family communication dysfunction (i.e., communication among family members is not as direct as it could be, and the content of verbal messages is not clear enough) plays a mediating role between tic severity and quality of life in children with TS. The mediating effect may be affected by sex and comorbidity. These insights offer valuable guidance for future clinical diagnosis and treatment, suggesting that addressing family communication dysfunction could be a vital component of managing TS and enhancing patient outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the families and children for their support and participation.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This investigation was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University Hospital, No. [2023]-E-05-R.

Informed consent statement: The need for patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Yan J S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L

Contributor Information

Shu-Jin Hu, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China.

Ying Li, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China.

Qing-Hao Yang, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China.

Kai Yang, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China.

Jin-Hyun Jun, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China.

Yong-Hua Cui, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China.

Tian-Yuan Lei, Department of Psychiatry, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing 100045, China. tianyuanlei@bch.com.cn.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Johnson KA, Worbe Y, Foote KD, Butson CR, Gunduz A, Okun MS. Tourette syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:147–158. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00303-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloch MH, Leckman JF. Clinical course of Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T. Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;47:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricketts EJ, Wolicki SB, Danielson ML, Rozenman M, McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Mink JW, Walkup JT, Woods DW, Bitsko RH. Academic, Interpersonal, Recreational, and Family Impairment in Children with Tourette Syndrome and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022;53:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01111-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roessner V, Eichele H, Stern JS, Skov L, Rizzo R, Debes NM, Nagy P, Cavanna AE, Termine C, Ganos C, Münchau A, Szejko N, Cath D, Müller-Vahl KR, Verdellen C, Hartmann A, Rothenberger A, Hoekstra PJ, Plessen KJ. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders-version 2.0. Part III: pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:425–441. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01899-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalifa N, von Knorring AL. Prevalence of tic disorders and Tourette syndrome in a Swedish school population. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:315–319. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson MM. A personal 35 year perspective on Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidities, and coexistent psychopathologies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:68–87. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scharf JM, Miller LL, Gauvin CA, Alabiso J, Mathews CA, Ben-Shlomo Y. Population prevalence of Tourette syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2015;30:221–228. doi: 10.1002/mds.26089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez-Colina AM, Eaton CK, Lee JL, LaMotte J, Blount RL. Health-related quality of life and psychosocial functioning in children with Tourette syndrome: parent-child agreement and comparison to healthy norms. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:326–332. doi: 10.1177/0883073814538507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Hare D, Helmes E, Reece J, Eapen V, McBain K. The Differential Impact of Tourette's Syndrome and Comorbid Diagnosis on the Quality of Life and Functioning of Diagnosed Children and Adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;29:30–36. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hesapçıoğlu ST, Tural MK, Kandil S. Kronik Tik Bozukluklarında Sosyodemografik, Klinik Özellikler ve Risk Etmenleri [Sociodemographic/Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with chronic tic disorders] Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2013;24:158–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cubo E, Gonzalez C, Ausin V, Delgado V, Saez S, Calvo S, Garcia Soto X, Cordero J, Kompoliti K, Louis ED, de la Fuente Anuncibay R. The Association of Poor Academic Performance with Tic Disorders: A Longitudinal, Mainstream School-Based Population Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48:155–163. doi: 10.1159/000479517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller-Vahl K, Dodel I, Müller N, Münchau A, Reese JP, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Dodel R, Oertel WH. Health-related quality of life in patients with Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Mov Disord. 2010;25:309–314. doi: 10.1002/mds.22900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire JF, Hanks C, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Murphy TK. Social deficits in children with chronic tic disorders: phenomenology, clinical correlates and quality of life. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong SB, Kim JW, Shin MS, Hong YC, Park EJ, Kim BN, Yoo HJ, Cho IH, Bhang SY, Cho SC. Impact of family environment on the development of tic disorders: epidemiologic evidence for an association. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25:50–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu P, Wu M, Huang P, Zhao X, Ji X. Children from nuclear families with bad parental relationship could develop tic symptoms. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1286. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermilion J, Augustine E, Adams HR, Vierhile A, Lewin AB, Thatcher A, McDermott MP, O'Connor T, Kurlan R, van Wijngaarden E, Murphy TK, Mink JW. Tic Disorders are Associated With Lower Child and Parent Quality of Life and Worse Family Functioning. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;105:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraft JT, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, Thomsen PH, Henriksen TB, Scahill L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of tic disorders in a community sample of school-age children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y, Zhang L, Wang F, Zhang P, Ye B, Liang Y. The effects of family structure and function on mental health during China's transition: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18:59. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0630-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herring S, Gray K, Taffe J, Tonge B, Sweeney D, Einfeld S. Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: associations with parental mental health and family functioning. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50:874–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisula E, Porębowicz-Dörsmann A. Family functioning, parenting stress and quality of life in mothers and fathers of Polish children with high functioning autism or Asperger syndrome. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedmann MS, McDermut WH, Solomon DA, Ryan CE, Keitner GI, Miller IW. Family functioning and mental illness: a comparison of psychiatric and nonclinical families. Fam Process. 1997;36:357–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azazy S, Nour-Eldein H, Salama H, Ismail M. Quality of life and family function of parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24:579–587. doi: 10.26719/2018.24.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman C, Murphy T, Scahill LD, Compton SN, Walkup J. Exploring the impact of chronic tic disorders on youth: results from the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42:219–242. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keitner GI. Family assessment in the medical setting. Adv Psychosom Med. 2012;32:203–222. doi: 10.1159/000330037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shek DT. Family functioning and psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior in chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. J Genet Psychol. 2002;163:497–502. doi: 10.1080/00221320209598698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fauber RL, Long N. Children in context: the role of the family in child psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:813–820. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson LR, Bitsko RH, Schieve LA, Visser SN. Tourette syndrome, parenting aggravation, and the contribution of co-occurring conditions among a nationally representative sample. Disabil Health J. 2013;6:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Storch EA, Murphy TK, Ricketts EJ, Woods DW, Walkup JW, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, Lewin AB, McCracken JT, Leckman JF, Scahill L. A multicenter examination and strategic revisions of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Neurology. 2018;90:e1711–e1719. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szejko N, Robinson S, Hartmann A, Ganos C, Debes NM, Skov L, Haas M, Rizzo R, Stern J, Münchau A, Czernecki V, Dietrich A, Murphy TL, Martino D, Tarnok Z, Hedderly T, Müller-Vahl KR, Cath DC. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders-version 2.0. Part I: assessment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:383–402. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavanna AE, Schrag A, Morley D, Orth M, Robertson MM, Joyce E, Critchley HD, Selai C. The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome-quality of life scale (GTS-QOL): development and validation. Neurology. 2008;71:1410–1416. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327890.02893.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wen F, Gu Y, Yan J, Liu J, Wang F, Yu L, Li Y, Cui Y. Revisiting the structure of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) in a sample of Chinese children with tic disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:394. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solís-García G, Jové-Blanco A, Chacón-Pascual A, Vázquez-López M, Castro-De Castro P, Carballo JJ, Pina-Camacho L, Miranda-Herrero MC. Quality of life and psychiatric comorbidities in pediatric patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Rev Neurol. 2021;73:339–344. doi: 10.33588/rn.7310.2021046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isaacs DA, Riordan HR, Claassen DO. Clinical Correlates of Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults With Chronic Tic Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:619854. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.619854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Levin S. The McMaster Model of Family Functioning. J Marriage Fam Couns. 1978;4:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and Validity*. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller IW, Kabacoff RI, Keitner GI, Epstein NB, Bishop DS. Family functioning in the families of psychiatric patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27:302–312. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(86)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staccini L, Tomba E, Grandi S, Keitner GI. The evaluation of family functioning by the family assessment device: a systematic review of studies in adult clinical populations. Fam Process. 2015;54:94–115. doi: 10.1111/famp.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elstner K, Selai CE, Trimble MR, Robertson MM. Quality of Life (QOL) of patients with Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:52–59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S, Zheng L, Zheng X, Zhang X, Yi M, Ma X. The Subjective Quality of Life in Young People With Tourette Syndrome in China. J Atten Disord. 2017;21:426–432. doi: 10.1177/1087054713518822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavanna AE, David K, Orth M, Robertson MM. Predictors during childhood of future health-related quality of life in adults with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2012;16:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman CL, Murphy TK, Scahill LD, Compton SN, Walkup JT. The impact of Tourette Syndrome in adults: results from the Tourette Syndrome impact survey. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:110–120. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9465-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huisman-van Dijk HM, Matthijssen SJMA, Stockmann RTS, Fritz AV, Cath DC. Effects of comorbidity on Tourette's tic severity and quality of life. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;140:390–398. doi: 10.1111/ane.13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carter AS, O'Donnell DA, Schultz RT, Scahill L, Leckman JF, Pauls DL. Social and emotional adjustment in children affected with Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome: associations with ADHD and family functioning. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edell-Fisher BH, Motta RW. Tourette syndrome: relation to children's and parents' self-concepts. Psychol Rep. 1990;66:539–545. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.66.2.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper C, Robertson MM, Livingston G. Psychological morbidity and caregiver burden in parents of children with Tourette's disorder and psychiatric comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1370–1375. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000085751.71002.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storch EA, Lack CW, Simons LE, Goodman WK, Murphy TK, Geffken GR. A measure of functional impairment in youth with Tourette's syndrome. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:950–959. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee MY, Chen YC, Wang HS, Chen DR. Parenting stress and related factors in parents of children with Tourette syndrome. J Nurs Res. 2007;15:165–174. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000387612.85897.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGuire JF, Arnold E, Park JM, Nadeau JM, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Living with tics: reduced impairment and improved quality of life for youth with chronic tic disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiller JW. Brief family therapy for childhood tic syndrome. Fam Process. 1978;17:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1978.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohammadi MR, Badrfam R, Khaleghi A, Ahmadi N, Hooshyari Z, Zandifar A. Lifetime Prevalence, Predictors and Comorbidities of Tic Disorders: A Population-Based Survey of Children and Adolescents in Iran. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022;53:1036–1046. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, Kerbeshian J, Robertson MM, Sandor P. An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:436–447. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eapen V, Snedden C, Črnčec R, Pick A, Sachdev P. Tourette syndrome, co-morbidities and quality of life. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:82–93. doi: 10.1177/0004867415594429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.