Abstract

Background and aims:

The needs of autistic individuals and their families are unique in each developmental phase, but this diversity is more palpable during adolescence. Literature generally presents a view that caregivers experience challenges in caring for autistic children, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where formal support services are uneven or unavailable. The present study explored the lived experiences of parents of autistic adolescents in the Indian context.

Methods:

In-depth interviews with 12 parents were analyzed using an interpretative phenomenological approach.

Results:

Three superordinate themes were derived: (a) Acceptance alongside recurring experiences of grief and loss, (b) post-traumatic growth and vicarious transformation, and (c) What after me? Planning for future care services with limited systemic support.

Beginning with the initial recognition and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, parents progressed through a series of experiences that strengthened and challenged their understanding and aided in their acceptance. Parents recognize their adolescents’ key attributes, growth, development, and persisting differences that could contribute to future challenges. Grief experiences, however, sporadic, persisted alongside acceptance.

Conclusion:

Despite challenges, families were adapting to the changing needs of the developmental phases in unique ways, with or without formal support available to them. Nonetheless, there is a considerable need to address the existing gaps and felt needs of parents, focusing on empowering parents and capacity building toward providing comprehensive services to autistic individuals with a lifespan approach.

Keywords: Autistic adolescents, autism, India, interpretative phenomenological analysis, parenting experiences

Key Messages:

The needs of autistic individuals and their families are unique in each developmental phase, but this diversity is more palpable during adolescence.

Beginning with the initial recognition and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, parents progressed through a series of experiences that strengthened and challenged their understanding and aided in their acceptance.

Despite challenges, families were adapting to the changing needs of the developmental phases in unique ways, with or without formal support available to them.

There is a considerable need to address the existing gaps and felt needs of parents.

The needs of autistic individuals i and their families are unique in each developmental phase, but this diversity is more palpable during adolescence. Parenting experiences also change with the developmental stage of the autistic individual and the family lifecycle. Parents, in response, reshape their coping and advocacy skills to address the needs specific to each stage. 1 Though community awareness and support services have increased over the last few decades,2,3 specific needs such as independent living and employability still need to be made available for many.4,5 Besides the characteristic socio-communication skill deficits, limited educational and employment opportunities are significant factors affecting socio-functional outcomes, especially during adolescence and emerging adulthood. 6 Literature generally presents a view that caregivers experience challenges in caring for autistic children, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), where formal support services are uneven or unavailable.7,8 Similar observations were made in the Indian settings, and the onus of longitudinal care of the autistic individual entirely rests on families.9–12 In this context, parental perceptions, felt needs, and the meaning-making of daily experiences, termed “lived experiences,” become very important in designing appropriate support services for families.

Qualitative research provides better opportunities for an in-depth understanding of lived experiences 13 and can inform service and policy implementation.14,15 Previous qualitative research in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) focusing on parenting experiences, challenges in accessing services, and transition needs from the perspectives of autistic individuals, families, and stakeholders are predominantly from high-income countries where families are more supported formally.15,16 Existing services in the LMIC are primarily the result of parental advocacy, which continues to impact systems and policy positively. In this study, we sought to understand the lived experiences of parenting an autistic child through adolescence and emerging adulthood, challenges related to developmental tasks, their felt needs, and future aspirations using qualitative methodology.

Methods

The study was conducted at the [Department], [city], India, from June 2020 to September 2021. Parents of adolescents aged 15–18 years with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD were eligible for participation. Trained child psychiatrists did diagnostic ascertainment following comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. Parental age, education, occupation, and socio-economic status were no bar for inclusion. Participants were 12 parents from eight families (seven mothers, five fathers) recruited through purposive sampling (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic Profiles of the Participants.

| S.No. | Participant ID | Age of the Adolescent | Gender | Current Educational Status | Comorbidity | Mother’s Age and Occupation | Father’s Age and Occupation |

| 1. | P01 | 17 | M | Special school | Comorbid moderate IDa | – | 50, professional |

| 2. | P02 | 15 | M | 9th grade | 46, professional | – | |

| 3. | P03 | 16 | F | 11th grade | 46, professional | – | |

| 4. | P04 | 15 | M | 7th grade | Comorbid mild ID | 45, homemaker | 46, professional |

| 5. | P05 | 16 | M | 10th grade | 45, professional | 48, professional | |

| 6. | P06 | 16 | M | Special school | Comorbid mild ID | 48, homemaker | – |

| 7. | P07 | 16 | M | 11th grade | 50, homemaker | 52, professional | |

| 8. | P08 | 15 | F | Special school | Comorbid moderate ID | 46, homemaker | 50, professional |

—Not participated; ID—Intellectual disability. aAs part of comprehensive diagnostic assessments, all children underwent clinical evaluation of intellectual and socio-adaptive functioning. Assessments such as the Vineland Social Maturity Scale, developmental screening tests, and intelligence assessments were available from the patient file. These assessments were conducted as part of routine clinical evaluation and not for study.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was adopted, 17 as it is best suited to gain an in-depth understanding of the parenting experiences in the context of ASD. The [Institute] Review Board approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval statement and informed consent statement is provided at the end of the methodology section.

Study Procedure

Phase 1: Development and Validation of the Interview Guide

HM developed the interview guide based on a comprehensive and systematic review of the literature and clinical experience of working with families of children with ASD under the supervision of the co-authors. Open-ended questions with prompts were developed to elicit subjective experiences related to critical areas in parenting and raising an adolescent with ASD (including experiences with receiving the diagnosis, navigating the services, handling issues specific to adolescence), concerns related to transition and the future, and felt needs (Interview guide: Supplement 1). The questions were arranged sequentially, reflecting phases of child development and experiences related to challenges across developmental stages. A funneling approach was followed, thus enabling the inquiry to proceed from general to specific topics. Sensitive topics such as “what after me” concerns and the impact of ASD on the family were introduced in the later part of the interview. The interview guide was kept flexible and iterative.

Stakeholder/Community Involvement

Six key professionals in child psychiatry, clinical psychology, rehabilitation, and qualitative research reviewed the interview guide. Experts reviewed the interview guide for objectivity, fluidity, ease of understanding, and comprehensiveness to study the intended experiences. Questions related to understanding the “parental perception of the adolescent’s experiences at school/therapy centers” were added based on expert suggestions. Two parents of adolescents with ASD reviewed the interview guide for clarity, comprehensiveness of content, and an insider’s perspective. Sensitive areas and potential ethical concerns from the parent’s viewpoint were discussed. Thus, the content validity of the interview schedule was established.

Following the pilot interviews (n = 2), additional questions related to first-hand-experience-based recommendations they would give for parents of young children with ASD and “child’s awareness about autism and diagnostic disclosures by parents” were included based on the frequency of questions and the key concerns that emerged.

Phase 2: In-depth Interviews

Parents of autistic adolescents attending the clinical services were contacted, and informed consent was obtained for study participation. The interviews were conducted through a video-conferencing platform. HM conducted all interviews in English and audio-recorded with participants’ consent. Feedback related to research participation and consent for future contact for respondent validation were taken. The duration of the interviews ranged from 1.45 to 2.15 hours. The researcher’s reflexivity journal and elaborate field notes were maintained at the end of each interview.

Researcher’s Position

Throughout the study, the researcher has been an observer, considering the participants to be experts in their experience. The researcher took a listener’s stance during the interviews to allow the participants’ voices to emerge. Being a mental health professional and having worked with families of autistic individuals, the analysis was also influenced by the researcher’s understanding; however, it is viewed as a constructive interpretation of the participants’ experiences.

Data Analysis

The analytic process followed the IPA approach. 17 This research attempts to understand parents’ experiences from their perspectives and what these experiences mean to them. The IPA’s core principles of reflexive engagement and its treatment of participants as experts can equalize the balance of power between participants and researchers and help bring the essence of their experiences to the surface. The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by HM. Each participant’s audio recording was listened to, and the transcript was read and re-read to familiarize them with the data obtained and to attain an essence of the meaning in each participant’s experience. The researcher’s field notes and the contents of the reflexivity journal were also included—initial comprehensive notes involved exploratory comments about the context and descriptive and initial interpretative comments. Analytical and interpretative comments were made during the subsequent readings.

The interpretative comments were transformed into emerging themes, a concise phrase more at a conceptual level involving frameworks from theories of child development, including differences in ASD, family systems, meaning-making, and transactional coping models. Seeking and identifying relationships between similar themes, clustering them together, and deriving superordinate themes representing a concept through abstraction and subsumption was followed for individual interviews. The final stage involved identifying patterns across the cases and how one theme could illuminate another case differently, keeping the individual participant’s context and idiographic commitment in focus. The transcripts were independently analyzed by co-authors (JVS and TK) to ensure consensus regarding superordinate and subordinate themes, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion, thereby achieving investigator triangulation. 18 Respondent validation could have provided opportunities for the participants to add to or challenge the researchers’ interpretations. However, in IPA, interpretations happen both during data collection and afterward. The “double hermeneutic” framework of IPA, a dynamic process where “first the participants attempt to make sense of their experiences; then, the researcher attempts to make sense of, and interpret, the participants’ accounts of their experiences,” allows the interviewer’s preliminary interpretations to be checked with participants during the interview process.

Results

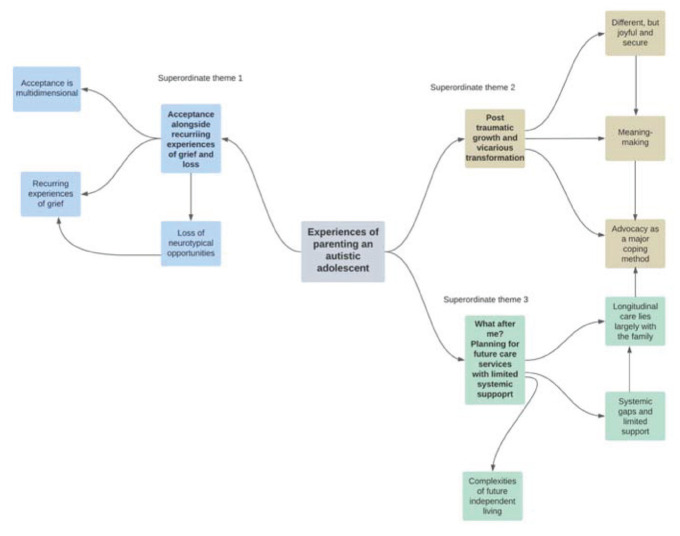

The socio-demographic details of the parents and the clinical profile of the autistic adolescents are provided in Table 1. The concept map (Figure 1) depicts the derivation of the superordinate and subordinate themes. Each theme is substantiated with representative excerpts from the interviews.

Figure 1. Concept Map: Derivation of the Superordinate and Subordinate Themes.

Superordinate Theme 1: Acceptance Alongside Recurring Experiences of Grief and Loss

Subtheme 1: Acceptance is Multidimensional

Renewed understanding and acceptance of ASD, expectations from the child and from “themselves as parents” occur as a gradual process. The various dimensions of acceptance were acceptance of the “diagnosis,” “outcome,” “identity,” and “of the child, with autism making no difference to the parenting experience….” From “being clueless” and “unaware,” parents recognize ASD as “just a label.” Parents moved from “disability” to “different abilities.” Acceptance appears to be a protective response, facilitating an optimistic perception of the parenting experience, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. For many parents, recognition of autism did not change the value of their child, and this strongly reflects how autism is not externalized as a disorder but rather integrated into the child’s identity.

Initially, we expected that there would be a cure, maybe today or tomorrow or the day after. We kept running behind outcomes for a long period. Now, we understand that we must put a strategic full stop somewhere. He is a God-given gift to us. We acknowledge he has his differences, and he is special and valuable. [moving from an illness to an identity model] [P01, father]

“From that time [diagnosis], I had accepted that he is not going to be a normal ii [neurotypical] child, and kept our expectations low, mainly related to academics. At the same time, we do not want to underestimate or over-expect from him.” [reframed expectations] [P02, mother]

Subtheme 2: Recurring Experiences of Grief

While ongoing understanding and acceptance are evident, parents continue to navigate through the grief of the loss of a neurotypical child and over their own parental identity. During intermittent periods of distress posed by recurring challenges, parents strived to comprehend them and attempt to move forward. Over time, grief is less intense; however, it continues to persist alongside positive experiences, post-traumatic growth, and hope. These recurring experiences of grief also seem to help parents prepare for their autistic child, who is expected to survive over the long term without parental support and inadequate formal support.

Every point is a challenge for parents like us; only the goals keep changing…. We must find a way that does not traumatize his inner self. Sometimes, we may appear happy to have accepted his condition. On the inside, there are constant worries about the future. We come back to square one very often, not knowing how to begin all over again. [P04, mother]

Subtheme 3: Loss of Neurotypical Opportunities

At this time point in their life, the majority of the parents were not overly concerned about themselves or societal stigma as much as they were about the impact of autism on the adolescent. This perception seems to have evolved gradually, with parents feeling empowered, more capable of navigating through the systems, advocating for their child, and at the same time, feeling guilty that “they have not done enough.” Experiences of grief and loss of color; the perception of their child’s life as “difficult” compared to neurotypical peers.

We are sometimes carried away by thoughts like “How things would have been if he was normal. He would have been in college, having fun just like other kids his age. We regret that he has missed all these opportunities, not that we missed a normal child…. If not for autism, he would not be dependent on us…. We have gone through that journey, and there is no looking back on our personal lives. I see it as an impact on his life than ours. [P01, father]

Parents recognize that their children can become lonely during adolescence because they do not find accepting peers. There could be attrition of existing peer relationships as neurotypical peers have differing interests. Parents report that though their adolescents perceive “they have friends,” they are not one among them. They also emphasize the importance of peer relationships as crucial to navigating societal challenges and promoting integration. Peer relationships are seen as opportunities for neurotypical children, which neurodiverse children are often deprived of. Despite challenges, most parents report that their adolescents desire friendships and strongly like school, and parents strive to ensure that school is a “happy place” for them. Parents yearn for their children to have enduring social connections and hope that these relationships are “fulfilling companionships and future support systems” for their autistic child.

For adolescents, we talk about peer interaction being important. However, there is none available. Peers of this age do not have the time or the frame of mind to interact with these [autistic] children, even if they have the intention to. Maybe they do not know how to…. By sensitizing peers in doing the right thing, we may help autistic kids come up to a certain level. [P03, mother]

Superordinate Theme 2: Post-traumatic Growth and Vicarious Transformation

Subtheme 1: Different but Joyful and Secure

Parents described positive admiration for their child while acknowledging challenges, particularly socio-communication difficulties. Parents recognize their children as “emotional beings” who are sensitive and perceptive yet qualitatively different in emotional expression compared to their peers. While acknowledging differences in social cognition and interpersonal reasoning, parents also see them positively and occasionally describe deficits as assets, for example, one parent described the child’s lack of social interests as “he has a secure world for himself.”

“Learning from the child,” “learning a new parenting template,” and “not underestimating and over-expecting from the child” have been helpful for most parents. Parents also highlighted the importance of “not having low aspirations for the child” as instrumental in facilitating positive developmental outcomes.

Subtheme 2: Meaning-making

While parenting an autistic child includes demands, parents often adapt well to their circumstances over time. Many parents reported personal growth and perceived transformative changes such as being more calm, tolerant, and having a non-judgmental attitude, and attribute these changes as a direct effect of raising an autistic child. These gradual transformative changes have contributed to increased self-efficacy and hope to meet future challenges. Transformative experiences are associated with positive admiration for their child, their temperamental traits, and their positive impact on others.

“I was a different person altogether. I am now more calm and perceptive. I can say I am more receptive. [My child] did change me as a person” [P03, mother]

“We are confident that when he grows up to be a young man, he will do good for himself and the people around. Parenting him has been an enriching experience compared to parenting my older [non-autistic] son.” [P08, father]

Most parents reflected on what “having a child with autism meant” to them. Articulated lessons learned as a result of being a “parent.” “Families” meaning-making frequently resulted in a changed world view to a positive outlook of life in general, and a greater appreciation of micro gains made by their children and acknowledged them as “their accomplishments as parents.” Positive meaning-making was associated with acceptance and adaptive coping and could increase the potential for adolescents to have a place they belong in the future. It also reflects mature defense mechanisms; parents use them when doing well.

“God knows whom to give such children and who can do the best for them. Because our kids are special, we also are ‘special parents’. This notion feels meaningful to us. It helped, rather propelled us through this journey.”

Subtheme 3: Advocacy as a Significant Coping Method

All parents have taken up advocacy roles at various times for their children and the broader autistic community. While advocating for their child is instrumental in obtaining a particular service or facilitating change, advocating for the broader group provides a sense of fulfillment.

“I have always been upfront with the schools,… that my child has autism. Recently, I presented at her school to the teachers how to identify children with different abilities…. A session with her classmates on how to be inclusive.” [P02, mother]

“When we speak to parents of other children with autism, we share our experiences. When they get to learn something new, there is a glow of happiness on their face. It is fulfilling. By our experiences, being helpful to other children is rewarding.” [P08, father]

Superordinate Theme 3: What After Me? Planning for Future Care Services with Limited Systemic Support

Subtheme 1: Complexities of Future Independent Living

Irrespective of cognitive abilities, all parents reported concerns related to independence in activities of daily living (ADL). Parental concerns reflected challenges their adolescents have in gaining autonomy, being able to navigate adult life without parental support, and the more considerable absence of services to help with independent living and community participation. Perceived improvement in academic competencies, self-regulation, and self-management in the background of good cognitive abilities provided a sense of hope for the future. However, a lack of competencies such as independence in ADL and higher-order skills, including social cognition and interpersonal reasoning, generated uncertainty and worry.

“He can study and get a degree in Math or science. But he has no idea what he should do when he is alone. It may be difficult to live alone without any support.” [Competencies for independent living and naivety] [P05, Father]

Parents anticipate their future roles based on the adolescent’s current cognitive and adaptive abilities. Parents of adolescents with good cognitive abilities envision their future roles as “faciliatory” while acknowledging the need for “continued support” due to social cognition and interpersonal reasoning gaps. On the other hand, parents of adolescents with intensive support often need to “come back to square one,” requiring supporting their adolescent in the following developmental task. There is a sense of time limitation, and parents revisit their accomplishments toward their child’s well-being and continued development, reflecting determination and uncertainty.

On the one hand, I am happy he is learning and improving. On the other hand, I have failed as a parent. I am worried that I have made him too dependent on us. He can care for some basic things,…but are those [basic things] sufficient to live independently in this world? [P04, mother]

Right now, he is completely dependent on us. We are working on training him to be self-dependent. We are yet to see results. This one lifetime is not enough to train children like [name]. I sometimes wonder, will he be able to do things alone when we are not around? [P06, mother]

Emerging sexuality among autistic adolescents is often not paralleled by the corresponding growth of sexual knowledge, especially concerning social norms and boundaries. Expression of sexuality and age-appropriate sexual functioning was often seen from the lens of “adaptive functioning” with a focus on personal hygiene and safety. Though parents take up opportunities for conversations around sex education, they are concerned about its practical application and consider the same as a critical skill for independent living.

“Since [name] is a girl, we face additional challenges.” Parents consider gender alongside the socio-communication challenges in evaluating personal safety in the absence of parents. Parents of adolescent girls expressed concerns related to menstrual hygiene, safety in relationships, and risk of abuse and victimization. Parental lack of awareness and a child’s limited cognitive abilities are perceived as limitations for sex education. At the same time, when parents see the merit of sensitizing their growing adolescents regarding sexuality, developmentally appropriate educational and training materials are perceived to be helpful.

We are more concerned because she is a girl. It brings in additional challenges. She is too innocent to understand if somebody approaches her with a vested interest. Though we speak to her about safety, we do not know how she would respond in an actual situation. She is taught about good and bad touch. She knows that is not right. Nevertheless, will she say “no” when someone touches her? I do not know. That is worrisome. [P02, mother]

Subtheme 2: Systemic Gaps and Limited Support

All parents reported challenges in identifying and navigating through the services and systems at various stages of their child’s development, more so during adolescence and transition toward adulthood. The early service-related challenges centered around lack of information, paucity of services, complete reliance on healthcare professionals for informational needs, and inadequate support from the healthcare and school systems, further compounded by issues of accessibility and affordability. Some parents coped by empowering themselves as a “parent-therapist” through training programs.

Several services, mainly in the private sector, are availed by individuals and families, depending on the intensity of support needs, level of integration and services availed during formative years, and comorbid conditions. Most parents perceived school as “generally supportive,” however, “inclusion does not happen in its true sense.” Lack of training and sensitization among the teachers and lack of curricular adaptation were perceived as significant challenges impacting effective integration, even for adolescents with good academic competencies.

I am not expecting academic support at school. From my perspective, these are his school years. He should have opportunities to interact with peers and enjoy the school environment. Children like [name] cannot be in this education system for long. He might have to be pulled out sooner or later. I see school as an opportunity for him to do what every other kid his age does. [P04, mother]

Among adolescents attending special schools, lack of support for continued services and abrupt disruption of ongoing services during adolescence are vital challenges. While available services cater to individuals with independence in ADLs, services for individuals with comorbid intellectual disability are almost non- existent. In the Indian context, specialized services for ASD are predominantly in the urban and private settings operating on a market-based economy, thus increasing disparities in service utilization. Also, ASD treatment services are associated with recurring costs posing financial constraints.

Many services are available for young children. When she turned 12, our therapist told us that there was nothing much [interventions] required at this age and suggested continuing home-based interventions. While we are guided during the early years, when our children reach adolescence, we [parents] are suddenly left in the dark. There are even fewer options after schooling. [P08, mother]

Subtheme 3: Longitudinal Care Lies Mainly with the Family

During adolescence, there is a progressive shift in priorities from a service-oriented focus to planning critical services for future independent living. Parents often have a “here and now focus,” and future severe care planning gets postponed or less prioritized. A universal concern was a lack of integrated and comprehensive services in the context of educational, treatment, vocational, and transition services to address the unique needs of adolescents.

Parents have been primary agents of change and actively involved in their adolescent’s treatment right from childhood. In addition to ongoing services, there is a felt need for parent training to double up as therapists, extending beyond early intervention. Parents also strive to provide social opportunities for their adolescents, sometimes doubling up as “companions.” While parental roles during adolescence are primarily facilitatory, parents of autistic adolescents continue to take up an intensive supportive role, causing role strain.

In the Indian context, longitudinal care of the autistic individual lies with the family or in the private sector, with limited formal support. Lack of availability and fit with existing services are significant challenges in planning long-term care after parents.

I have visited many residential facilities. I am often asked 1. “Why do you think he needs residential care? He can take care of himself and is attending vocational training. It would help if you looked for job option”. 2. “What makes you look for residential care at this point? It should have been considered when he was ten years old. It is difficult to handle behavior problems in adolescents” Some institutes have also said, “Do you think he is a burden to you? You can take care of him at home.” Is taking care of daily needs enough to survive in this world? What will he do after us? He has no place to go to.

In most families, continued caregiving is provided by the mothers, with the father’s participation being limited to engagement in leisure activities and providing emotional support for mothers. Only in four families were fathers engaged in specific caregiving roles, often a recent transition. Also, in the current social structure in urban India, most families are nuclear and do not have extended family to support them in longitudinal care. Often, both parents are employed and trying hard to secure financial support for the entire lifespan of their autistic child, with which they could live without having to burden other family members, especially siblings. However, narratives reflect that a secure future seems uncertain and out of reach.

He is a young child [typically developing sibling], just 11 years old. He is a part of the family…and internalizes our efforts daily. It is too early to engage him in discussions about his brother’s condition or pin our expectations on him. He would have his personal life, and we do not want to expect him to care for [name] in his adulthood. We do not want to burden him. We are trying our best to secure his future, but things seem uncertain. [P01, father]

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the experiences of parenting an autistic child through adolescence and emerging adulthood using an interpretative phenomenological framework. The themes are anticipated to help us understand the unique experiences that could further inform services. Family forms an integral part of the immediate microsystem and mediates the autistic individual and the larger world. In countries like India, where there is limited systemic support, the care of autistic individuals across their lifespan lies predominantly with the family.9,19 Despite challenges, the majority perceived their parenting experience as “transformative” and were “successfully adapting,” catering to the needs of their adolescent, and each family’s adaptation is unique. Literature on parenting children with disabilities has predominantly focused on challenging experiences and formulating specific interventions. 20 However, understanding the characteristics, attitudes, and processes adopted by families with “successful adaptation” is equally important to inform interventions that foster family resilience.21,22

Transformative changes in the understanding of autism and the personal growth of parents facilitated greater acceptance and adaptive coping. Parents actively involved themselves in the child’s treatment and gained a different identity, experience, and empowerment. Parents have moved from viewing autism as an “illness/disorder” to embracing neurodiversity, which might have helped reframe their views and expectations, thus leading to adaptation and resilience. 21 Though parents had difficult experiences during the initial years, the very experience of parenting and perceived support systems fostered a changed perception of their sense of self.19,23 In this study, families could be considered “resilient” despite multiple adversities and challenges posed by the socio-cultural-political systems, over and above the challenges related to ASD.

The renewed understanding of ASD over time helped reframe expectations for the adolescents and themselves as parents. The acceptance process varies for different parents; parental beliefs and value systems reshape their perceptions. Also, good academic competencies in adolescents facilitated acceptance. This could be due to (a) valence given to academic competencies in the socio-cultural context and (b) academic competencies reflecting the child’s ability to utilize opportunities comparable to neurotypical peers (e.g., mainstream schooling).

While acceptance is ongoing, recurring grief is experienced at each developmental phase, transition, and new challenge.19,24 Parents understand the lack of normative role transitions of the autistic adolescent, and in turn of themselves, which is reflected in their narrative accounts. Experiences of loss and grief are reported at key phases: receiving the diagnosis, understanding the need for sustained efforts over the long term rather than the mobilization of resources over the short term, and determination to contribute to the child’s growth while also being reminded of time limitations, loss of neurotypical opportunities for their adolescent, re-emerging grief when milestones pass unmet, feelings of “have I done enough for my child,” and uncertainty about the future, in the absence of parents. Grief experiences illustrate the everyday battle parents fight against the world to secure a safe future that seems to be forever out of reach, accentuated by the lack of a social safety net and support systems other than parents. This recurring grief also facilitates adaptability. 25 In clinical practice, it is essential to systematically assess for grief, and providing grief support should be one of the critical treatment goals.

School is seen as a developmental context providing opportunities closer to neurotypical peers and expected to foster the autistic adolescent’s development through accommodation rather than exclusion. Schools claiming to be inclusive expect autistic adolescents to participate and perform on par with peers without considering their unique abilities and support needs; as a result, academic learning could be less meaningful. Lack of curricular adaptation and individualized education plans was a significant concern compared to Western studies. 15 Inclusion in mainstream schools without providing reasonable accommodations will not serve the purpose. 26 Most parents drew upon support from schools and perceived instrumental, social, and practical support as helpful to navigate the systemic challenges. Emphasizing the need for schools to reconsider their approach to inclusion, all parents view mainstream schooling as a facilitating environment for social interaction, and autistic adolescents should not be deprived of this opportunity because of structural and systemic challenges.

Existing studies suggest a disjunction between the desire to socialize with friends and achieving this successfully, given the complexities of adolescent social relationships.27,28 In this study, parents identified gaps in the quality of peer relationships compared to the parent-reported adolescent’s perceptions. Parents and adolescents operate from different definitions of friendships, one of neurotypical versus neurodiverse. Discrepancies in parents’ perspectives also reflect their expectations of peer relationships as future companionship or support toward independent living versus the adolescents developmentally being in the “here and now.” 29 Contrary to the literature, only a few parents perceived the need for creating a social circle with adolescents who were neurodiverse. The majority expected support from neurotypical peers in schools. The preference for neurotypical peer relationships may also have to do with parents being concerned that their children may learn or adopt maladaptive behaviors from more neurodiverse peers. While it is essential to sensitize neurotypical peers, attempts to provide opportunities to interact with neurodiverse peers within and outside school networks may help foster relationships and a sense of belonging. 30

Prevailing systemic gaps and consequent challenges can be viewed through the following perspectives: (a) Parents seek and utilize systemic support whenever available. (b) When gaps and challenges increase, especially during adolescence, parents feel the systems could have helped them better. (c) A combination of the inadequacy of systemic efforts and the inherent long-term support needs of autistic individuals leaves families with a lack of a safety net for longitudinal care. Considering skill-building and mechanisms to promote semi-independent or semi-supported living while transitioning to adult roles is crucial. There is a felt need for informational support, longitudinal care models, visible and accessible community-based support in active collaboration with the families, and a solid political will to develop systemic solutions rooted firmly in community-supported mechanisms to facilitate continued care of autistic individuals after the parent.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies on the experiences and felt needs of parents of autistic adolescents in the Indian context. Given the heterogeneity in clinical presentation and support needs among autistic individuals, homogeneity is somewhat compromised. Respondent validation was not done, and this is a limitation. The results should be interpreted in light of the socio-demographic and clinical profile and developmental competencies of autistic adolescents. A detailed description of the same could not be attempted, given the limitations in manuscript length. All participants were from upper-middle socio-economic status, English-speaking, and had navigated through the system enough to be able to access resources for their child. This may be different from the experience of parents who do not have comparable resources.

Conclusion and Implications for Future Research

The findings illustrate a predominantly successful adaptation of the families interviewed. Translating clinically relevant research findings into meaningful actions is a critical challenge. Based on the study findings, an intervention manual addresses the felt needs. Policies need to articulate the importance of a strengths-based approach and promotion of resilience factors in working with families of autistic individuals and capacity building toward providing comprehensive services across age bands and a social safety net for longitudinal care. Respectful and participatory approaches to autism research are integral to achieving consistent and comprehensive services.

Notes

We have moved between first-person and identity-first language use throughout the proposal. We recognize that different individuals make different choices, and we respect every individual’s choice.

The word “normal” is used verbatim from the interview excerpts. The researchers acknowledge the connotation of the term, “normal” in verbatim excerpts from the transcripts refer to being “neurotypical.”

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval Statement: The study was approved by the Institute Review Board, National Institiute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Ref No: NIMH/DO/(Beh. Sc. Div)/2019, dated 28.09.2020.

Consent Statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Volkmar FR, Reichow B, McPartland JC, editors. Adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy A, Perry A. Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: a review of the literature. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011; 5:1271–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barua M, Kaushik JS, Gulati S. Legal provisions, educational services, and health care across the lifespan for autism spectrum disorders in India. Ind J of Pediatr, 2017; 84: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magiati I, Tay XW, Howlin P. Cognitive, language, social and behavioral outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review of longitudinal follow-up studies in adulthood. Clin Psychol Rev, 2014; 34: 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker E, Stavropoulos KK, Baker BL, et al. Daily living skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: implications for intervention and independence. Res Autism Spectr Disord, 2021; 83: 101761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cederlund M, Hagberg B, Billstedt E, et al. Asperger syndrome and autism: a comparative longitudinal follow-up study more than 5 years after original diagnosis. J Autism Dev Disord, 2008; 38: 72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace S, Fein D, Rosanoff M, et al. A global public health strategy for autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res, 2012; 5: 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman A, Divan G, Hamdani SU, et al. Effectiveness of the parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder in south Asia in India and Pakistan (PASS): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Psych, 2016; 3: 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daley TC, Weisner T, Singhal N. Adults with autism in India: a mixed-method approach to make meaning of daily routines. Soc Sci Med, 2014; 116: 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Divan G, Vajaratkar V, Desai MU, et al. Challenges, coping strategies, and unmet needs of families with a child with autism spectrum disorder in Goa, India. Autism Res, 2012; 5: 190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishore MT. Disability impact and coping in mothers of children with intellectual disabilities and multiple disabilities. J Intellect Disabil, 2011; 15: 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanathan P, Kishore MT, Seshadri SP. Lived experiences of siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder in India: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Ind J Psych Med, 2022; 44: 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard K, Katsos N, Gibson J. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in autism research. Autism, 2019; 23: 1871–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bölte S. The power of words: is qualitative research as important as quantitative research in the study of autism? Autism, 2014; 18: 67–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson KA, Sosnowy C, Kuo AA, et al. Transition of individuals with autism to adulthood: a review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics, 2018; 141: S318–S327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mount N, Dillon G. Parents’ experiences of living with an adolescent diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Educ Child Psychol, 2014; 31: 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JA, Shinebourne P. Interpretative phenomenological analysis 2012. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guion LA. Triangulation: establishing the validity of qualitative studies. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, EDIS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young S, Shakespeare-Finch J, Obst P. Raising a child with a disability: a one-year qualitative investigation of parent distress and personal growth. Disabil Soc, 2020; 35: 629–653. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McConnell D, Savage A, Breitkreuz R. Resilience in families raising children with disabilities and behavior problems. Res Dev Disabil, 2014; 35(4): 833–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayat M. Evidence of resilience in families of children with autism. J Intellect Disabil Res, 2007; 51: 702–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li-Tsang CW, Yau MK, Yuen HK. Success in parenting children with developmental disabilities: some characteristics, attitudes and adaptive coping skills. British J Dev Disabil, 2001; 47: 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Counselman-Carpenter EA. The presence of post-traumatic growth (PTG) in mothers whose children are born unexpectedly with Down syndrome. J Intellect Dev Dis, 2017; 4: 351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newsom CR, Weitlauf AS, Taylor CM, et al. Parenting adults with ASD: lessons for researchers and clinicians. Narrat Inq Bioeth, 2012; 2: 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bravo-Benítez J, Pérez-Marfil MN, Román-Alegre B, et al. Grief experiences in family caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019; 16: 4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morewood GD, Humphrey N, Symes W. Mainstreaming autism: making it work. Good Autism Pract: GAP. 2011; 12: 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauminger N, Solomon M, Aviezer A, et al. Children with autism and their friends: a multidimensional study of friendship in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 2008; 36: 135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Hagan S, Hebron J. Perceptions of friendship among adolescents with autism spectrum conditions in a mainstream high school resource provision. Eur J Spec Needs Educ, 2017; 32: 314–328. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teti M, Cheak-Zamora N, Bauerband LA, et al. A qualitative comparison of caregiver and youth with autism perceptions of sexuality and relationship experiences. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 2019; 40: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crompton CJ, Hallett S, Ropar D, et al. ‘I never realized everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: a thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism, 2020; 24: 1438–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]