Abstract

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a genetic multisystem ectopic calcification disorder caused by inactivating mutations in the ABCC6 gene encoding ABCC6, a hepatic efflux transporter. ABCC6-mediated ATP secretion by the liver is the main source of a potent endogenous calcification inhibitor, plasma inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi); the deficiency of plasma PPi underpins PXE. Recent studies demonstrated that INZ-701, a recombinant human ENPP1 that generates PPi and is now in clinical trials, restored plasma PPi levels and prevented ectopic calcification in the muzzle skin of Abcc6−/−mice. This study examined the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and potency of a new ENPP1-Fc isoform, BL-1118, in Abcc6−/− mice. When Abcc6−/− mice received a single subcutaneous injection of BL-1118 at 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg/kg, they had dose-dependent elevations in plasma ENPP1 enzyme activity and PPi levels, with an enzyme half-life of approximately 100 h. When Abcc6−/− mice were injected weekly from 5 to 15 weeks of age, BL-1118 dose-dependently increased steady-state plasma ENPP1 activity and PPi levels and significantly reduced ectopic calcification in the muzzle skin and kidneys. These results suggest that BL-1118 is a promising second generation enzyme therapy for PXE, the first generation of which is currently in clinical testing.

Keywords: ABCC6, ectopic calcification, ENPP1, enzyme therapy, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, pyrophosphate

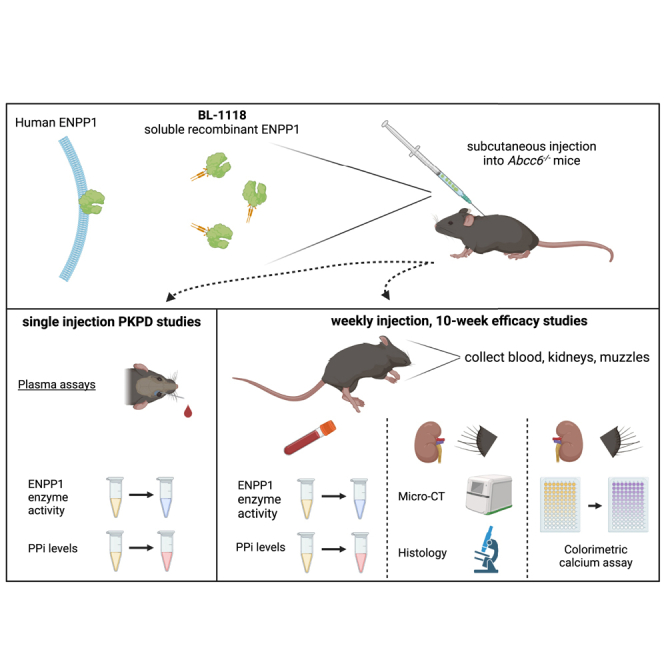

Graphical abstract

Li and colleagues demonstrated that a recombinant ENPP1 enzyme, which is a therapeutic protein biologic and the principal PPi-generating enzyme, corrects the underlying plasma PPi deficit and inhibits ectopic calcification in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), a genetic multisystem ectopic calcification disorder currently lacking preventive or therapeutic options.

Introduction

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE; OMIM: 264800) is an autosome recessive disorder characterized by a late-onset yet progressive accumulation of calcium hydroxyapatite outside of the skeletal system, specifically in the skin, eyes, and arterial blood vessels. Most patients with PXE carry loss-of-function mutations in the ABCC6 gene,1,2,3 which can also cause generalized arterial calcification of infancy type 2 (GACI2; OMIM: 614473), an exceedingly severe autosomal recessive disorder characterized by congenital calcification of arterial blood vessels.4 No specific FDA-approved treatment is currently available for ABCC6 deficiency.

The ABCC6 gene encodes ABCC6, a hepatic transmembrane efflux transporter. ABCC6 mediates ATP release from hepatocytes to the extracellular space, where ATP is converted by an ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase, ENPP1, to AMP and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi),5,6 the latter being a potent physiologic inhibitor of ectopic calcification.7,8 ENPP1 is the principal enzyme generating extracellular PPi, as Enpp1-deficient mice and patients with ENPP1 deficiency have minimal plasma PPi and present with extensive vascular calcification.9,10,11 In PXE, ABCC6 deficiency impairs the hepatic release of extracellular ATP, the precursor of PPi. In addition, ENPP1 expression is reduced in PXE.12,13,14 Due to the low extracellular ATP pool and reduced ENPP1 expression, the plasma PPi levels in Abcc6 KO mice and patients with PXE are reduced to about 30%–50% of controls.5 These findings underpin the drive to develop ENPP1-targeted therapies for PXE.

Previous studies have shown that overexpression of the human ENPP1 transgene normalized plasma PPi levels and significantly reduced ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice.15 These results prompted the development of an ENPP1 enzyme biologic for the treatment of PXE: a soluble recombinant human ENPP1-Fc enzyme, INZ-701, consisting of the extracellular domain of ENPP1 fused to the Fc domain of immunoglobulin (Ig)G1. Our previous studies demonstrated that daily or every other day subcutaneous injections of INZ-701 increased plasma PPi levels and completely prevented ectopic calcification in Enpp1-deficient mice on regular chow.16,17 The efficacy of various isoforms of ENPP1-Fc in Abcc6 and Enpp1-deficienct mice on the cardiovascular and bone phenotypes of ENPP1 deficiency was confirmed by Alexion Pharmaceuticals and Inozyme Pharma.11,16,18,19 INZ-701 also prevented ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice, demonstrating the reliability and reproducibility of the potency of ENPP1-Fc.17 In these studies, INZ-701 was injected every other day at high doses of 2 and 10 mg/kg.16 In theory, extending the dosing interval of ENPP1-Fc would enable extended, cost-efficient preclinical studies to be performed and would enhance patient compliance in the chronic administration of a preventative enzyme therapy, such as in the treatment of PXE. Thus, a potent ENPP1-Fc, BL-1118, was developed through protein engineering, glycan optimization, and a novel biomanufacturing platform with improved pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and in vivo activity.20 This study examined the PK, PD, and efficacy of BL-1118 on ectopic calcification in an Abcc6−/− mouse model of PXE.

Results

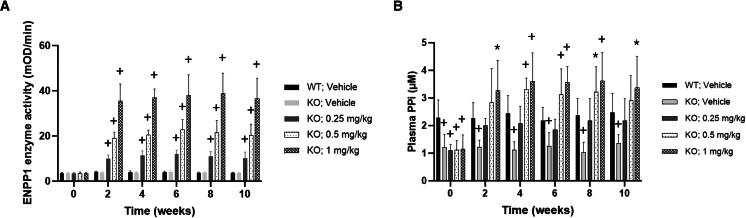

BL-1118 increased plasma ENPP1 activity and PPi concentration in Abcc6−/− mice

A single subcutaneous injection of BL-1118 at 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg/kg resulted in a dose-dependent increase of plasma ENPP1 activity in Abcc6−/− mice maintained on the control diet (Figure 1A). The ENPP1 enzyme bioavailability was measured by the area under the curve (AUC). Compared to Abcc6−/− mice dosed with 0.25 mg/kg, the activity of ENPP1 in plasma was 1.88- and 3.41-fold higher in the AUC in the Abcc6−/− mice dosed at 0.5 and 1 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 1A). Enzyme half-life results were 109, 100, and 113 h for 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

PK and PD effects of BL-1118 in Abcc6−/− mice after a single injection

Abcc6−/− mice were injected subcutaneously with 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg/kg of enzyme. Blood samples were collected at eight time points via retro-orbital bleeds.

(A) ENPP1 enzyme activity vs. time plots to highlight the AUC of the enzyme.

(B) The PK analysis of the recombinant ENPP1 enzyme. The fractional ENPP1 enzyme activity, corresponding to the fractional activity compared with peak plasma concentration (Cmax), was sampled in mice at eight time points over 239 h.

(C) The PD effect after a single injection of 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg/kg of enzyme, as measured by plasma PPi concentrations in Abcc6−/− mice. The shaded areas represent the baseline levels of PPi in plasma of WT and KO mice. Results are mean (SD). n = 6 blood samples per time point.

Consistent with published findings,5,21 Abcc6−/− mice plasma PPi levels were ∼40% of wild type (WT) (Figure 1C). Plasma PPi concentrations were significantly increased in Abcc6−/− mice injected with BL-1118, indicating the presence of sufficient ATP substrate for ENPP1 to normalize plasma PPi. Also, a single injection of the enzyme at 0.5 and 1 mg/kg restored physiological levels of PPi that maintained or exceeded physiological levels for up to 239 h (∼10 days) (Figure 1C), suggesting that weekly injections of the enzyme would maintain plasma PPi at therapeutic levels.

BL-1118 prevented ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice

Next, we analyzed the effects of weekly BL-1118 treatment on ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice. The spontaneous ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice is slowly progressive, with the earliest site being the connective tissue dermal sheath of vibrissae in muzzle skin.22 The vibrissae calcification in Abcc6−/− mice occurs as early as 5–6 weeks postnatally. The calcification of other organs, including kidneys, occurs late in life, but it can be accelerated by an experimental diet high in phosphorus and low in magnesium.23 Therefore, we conducted an efficacy study with BL-1118 treatment initiated in Abcc6−/− mice at 5 weeks of age, just as ectopic calcification started to develop, and continued the treatments for an additional 10 weeks on the acceleration diet.

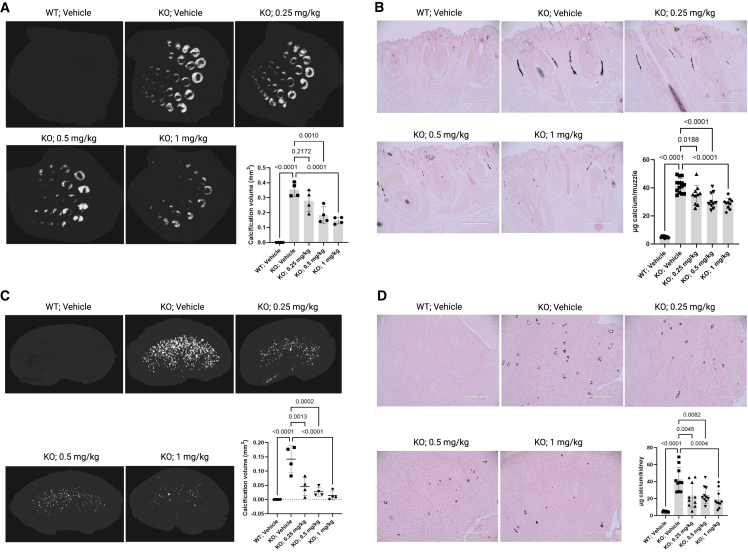

ENPP1 enzyme activity and PPi in plasma were analyzed in Abcc6−/− mice before they received the first injection of the enzyme, then every 2 weeks. Only background levels of ENPP1 activity were detectible in the plasma of controls (WT and knockout [KO] mice) (Figure 2A). The steady-state plasma ENPP1 activity in the Abcc6−/− mice dosed with BL-1118 increased dose dependently (Figure 2A). Weekly administration of 0.25 mg/kg BL-1118 in the Abcc6−/− mice increased plasma PPi to levels similar to those of WT mice, whereas the plasma PPi levels of Abcc6−/− mice dosed with 0.5 and 1 mg/kg BL-1118 exceeded WT levels (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Steady-state biomarkers in Abcc6−/− mice after 10 week BL-1118 treatment

(A) Plasma ENPP1 activity.

(B) Plasma PPi concentrations.

Vehicle-treated groups of WT mice and Abcc6−/− mice serve as controls of baseline levels of ENPP1 activity and PPi concentration in plasma. Values were expressed as mean (SD); ∗p < 0.05 and +p < 0.01 compared to WT group for the same time points. n = 10 mice per group (5 male and 5 female). WT, wild type. KO, knockout.

The degree of ectopic calcification was analyzed in the muzzle skin and kidneys. First, the calcification was imaged by micro-computed tomography (μCT) scanning, and the calcification volume was quantified (Figures 3A–3C), demonstrating extensive calcification in the tissues of KO mice. Abcc6−/− mice receiving BL-1118 had significantly lower amounts of calcification. The severity of ectopic calcification was assessed by semi-quantitative histological evaluation (Figures 3B–3D). Calcium-specific von Kossa staining detected robust calcification in the dermal sheath of vibrissae and kidneys in the KO mice and significantly reduced calcification in the treated mice. The most pronounced calcification in the kidneys occurred in the medullary tubules at the cortical-medullary junction. The efficacy of treatments was corroborated by tissue calcium contents measured by a chemical assay (Figures 3B–3D).

Figure 3.

Assessment of ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice after 10 week BL-1118 treatment

(A) μCT images of muzzle skin biopsies and quantification of calcification volume. n = 4 mice per group (2 male and 2 female).

(B) von Kossa-stained muzzle biopsies and quantification of calcium content. n = 10 mice per group (5 male and 5 female).

(C) μCT images of kidneys and quantification of calcification volume. n = 4 mice per group (2 male and 2 female).

(D) von Kossa-stained kidneys and quantification of calcium content. n = 10 mice per group (5 male and 5 female).

The Abcc6−/− control mice developed extensive ectopic calcification in the muzzle skin and kidneys. The WT mice were entirely negative for calcification. The Abcc6−/− mice administered BL-1118 demonstrated significantly reduced calcification compared to vehicle-treated Abcc6−/− control mice. Values were expressed as mean (SD); WT, wild type. KO, knockout.

Discussion

A highly potent ENPP1-Fc isoform, BL-1118, was engineered to enable longer dosing intervals. BL-1118 was produced in CHO K1 cells in the research setting,24 in contrast to INZ-701, which is produced in CHO cells using good manufacturing practice (GMP) techniques. The background glycosylation patterns of these two cell lines are vastly different, which will directly impact the PK of the enzyme biologics produced in the differing cell lines. However, side-by-side PK and PD comparison of BL-1118 and the research prototype of INZ-701, called 770, was published.20 Specifically, in Enpp1-deficient mice, BL-1118 increased the plasma half-life by ∼5.5-fold and increased drug exposure by 13-fold when administered at a 10-fold lower dose than the parental enzyme INZ-701.20 This study evaluated the PK, PD, and potency of BL-1118 in Abcc6−/− mice. BL-1118 increased plasma PPi levels in a sustained and bioavailable manner. Our previous findings showed that with an every other day subcutaneous injection of 2 mg/kg, the parental enzyme in Abcc6−/− mice normalized steady-state plasma PPi to the levels of WT mice.17 In the present study, a similar effect was observed in the same mouse model when BL-1118 was injected weekly at a dose as low as 0.25 mg/kg. BL-1118 treatment significantly reduced ectopic calcification in muzzle skin and kidneys, which were examined by three independent assays—μCT imaging, histopathology, and a quantitative chemical assay for calcium. One limitation of our study is that the ENPP1 downstream products of ATP purinergic metabolism, such as AMP and adenosine, which regulate ectopic calcification,25 were not analyzed.

The half-life of BL-1118 in Abcc6−/− mice was approximately 4 days. The half-life of protein therapeutics in rodents is typically 20%–25% of that in primates,26 supporting a bi-monthly or monthly dosing schedule for BL-1118 in humans, which is an attractive dosing scheme for the life-long enzyme therapy required in PXE. In this context, the less frequent dosing regimen of our ENPP1 biologic is far superior to current FDA-approved enzyme therapy approaches for other clinical conditions. Specifically, the accepted standard for the dosing frequency of hemophilia A in humans is intravenous doses of recombinant blood coagulation factor VIII as frequently as four times a day to control bleeding. Asfotase alpha, the first approved enzyme replacement therapy for hypophosphatasia, which is a life-threatening metabolic disorder, is injected as frequently as six times a week subcutaneously. Such frequent daily or weekly subcutaneous or intravenous injection therapies are routinely used in enzyme replacement therapy for metabolic disorders. Therefore, the extended dosing intervals of BL-1118 would be clinically preferable as the chronic therapy for patients with PXE. However, ENPP1 enzyme therapy does not equate to the functional replacement of ABCC6, which may ameliorate the therapeutic potency in PXE and GACI2. A combined therapy of ENPP1 enzyme and inhibitors of the DNA damage response/PARP1 signaling pathway operating independent of PPi27 might have the potential to achieve a complete arrest of ectopic calcification in PXE. Additional studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Materials and methods

Mice and treatments

The Abcc6−/− mouse was generated by targeted deletion of the Abcc6 gene and maintained on C57BL/6J background.22 BL-1118 was formulated in 1× PBS supplemented with 20 μM CaCl2 and 20 μM ZnCl2. The Abcc6−/− mice were administered BL-1118 subcutaneously at doses of 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg/kg. The mice were divided into two studies: (1) a PK and PD study and (2) a calcification-prevention study. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University.

In the PK and PD study, blood samples were collected by retro-orbital bleeds at 0, 6, 12, 21, 50, 90, 191, and 239 h in Abcc6−/− mice (5 per group) after a single injection of the enzyme. These mice were fed a standard rodent diet (Lab Diet 5010; PMI Nutrition, Brentwood, MO, USA).

In the calcification-prevention study, the Abcc6−/− mice began treatment at 5 weeks of age, the earliest stages of ectopic calcification in these mice.22 Mice were maintained on an acceleration diet (Envigo, rodent diet TD.00442, Madison, WI, USA) from 5 to 15 weeks of age. Compared with the standard rodent diet, the percentage of absorbable phosphorus (non-phytate) was increased by 2-fold (from 0.43% to 0.85%) and magnesium was decreased by 5.5-fold (from 0.22% to 0.04%) in the acceleration diet. BL-1118 was injected weekly. To suppress the potential immune response to the human enzyme, all mice were intraperitoneally administered 40 μg GK-1.5, an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1 day before the first injection of the enzyme, followed by a weekly boost of 25 μg.16,17,24 The controls were WT and Abcc6−/− mice receiving vehicle (1× PBS supplemented with 20 μM CaCl2 and 20 μM ZnCl2) and GK-1.5 injections. Each group was composed of five male and five female mice. Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital bleeds every 2 weeks.

PK and PD

Enzyme activity in plasma was quantitated as the optical density change per unit time (mOD/min) due to hydrolysis of the colorimetric substrate pNP-TMP.28 The assay buffer (1 M Tris [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 20 μM CaCl2, 20 μM ZnCl2, 2 mM pNP-TMP) was used as a blank control. The drug exposure was expressed as the AUC. For half-life calculations, the velocity values were converted to the percentage of activity and plotted in GraphPad Prism 9. The half-life of enzyme activity was calculated from its correspondent PK parameters, elimination (ke) and absorption (ka) rate constants, as described previously.20,24 The PPi concentrations were measured in platelet-free plasma using ATP sulfurylase to convert PPi into ATP in the presence of excess adenosine 5′ phosphosulfate followed by a luminescent assay of ATP.5,21 Blank control was 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) in the PPi assays.

Analysis of ectopic calcification

The left-side muzzle skin biopsies and kidneys were fixed in formol followed by μCT using a SkyScan 1275 scanner (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). Scans were acquired at source voltage of 55 kV, source current of 181 μA, and image pixel size of 15 μm, as described previously.29 The calcified tissue volume for each sample was calculated using CTAn’s three-dimensional (3D) analysis function. These tissues were then processed and embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with von Kossa. To quantify the amount of calcium, the right-side muzzle skin biopsies and kidneys were decalcified with 1.0 M HCl. The content of solubilized calcium was measured by a colorimetric assay (Stanbio Laboratory, Boerne, TX, USA).

Statistical analysis

The results in different groups of mice were analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVA. A p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were completed using GraphPad Prism 9.

Data and code availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Albert Paredes Rodriguez for technical assistance. This study was supported by PXE International, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R21AR080277, and Inozyme Pharma.

Author contributions

Q.L. designed the research study. D.T.B. and P.R.S. provided the recombinant ENPP1 enzyme. I.J.J., D.O.-Y., and Q.L. carried out experiments. I.J.J., D.O.-Y., and Q.L. analyzed the data. Q.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

D.T.B. and P.R.S. are inventors on patents owned by Yale University for therapeutics treating ENPP1 deficiency. D.T.B. is an equity holder and receives research and consulting support from Inozyme Pharma, Inc.

References

- 1.Bergen A.A., Plomp A.S., Schuurman E.J., Terry S., Breuning M., Dauwerse H., Swart J., Kool M., van Soest S., Baas F., et al. Mutations in ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:228–231. doi: 10.1038/76109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Saux O., Urban Z., Tschuch C., Csiszar K., Bacchelli B., Quaglino D., Pasquali-Ronchetti I., Pope F.M., Richards A., Terry S., et al. Mutations in a gene encoding an ABC transporter cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:223–227. doi: 10.1038/76102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringpfeil F., Lebwohl M.G., Christiano A.M., Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: mutations in the MRP6 gene encoding a transmembrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6001–6006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100041297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nitschke Y., Baujat G., Botschen U., Wittkampf T., du Moulin M., Stella J., Le Merrer M., Guest G., Lambot K., Tazarourte-Pinturier M.F., et al. Generalized arterial calcification of infancy and pseudoxanthoma elasticum can be caused by mutations in either ENPP1 or ABCC6. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen R.S., Duijst S., Mahakena S., Sommer D., Szeri F., Váradi A., Plomp A., Bergen A.A., Oude Elferink R.P.J., Borst P., van de Wetering K. ABCC6-mediated ATP secretion by the liver is the main source of the mineralization inhibitor inorganic pyrophosphate in the systemic circulation-brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014;34:1985–1989. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.114.304017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansen R.S., Küçükosmanoglu A., de Haas M., Sapthu S., Otero J.A., Hegman I.E.M., Bergen A.A.B., Gorgels T.G.M.F., Borst P., van de Wetering K. ABCC6 prevents ectopic mineralization seen in pseudoxanthoma elasticum by inducing cellular nucleotide release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20206–20211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319582110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orriss I.R., Arnett T.R., Russell R.G.G. Pyrophosphate: a key inhibitor of mineralisation. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016;28:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ralph D., van de Wetering K., Uitto J., Li Q. Inorganic pyrophosphate deficiency syndromes and potential treatments for pathologic tissue calcification. Am. J. Pathol. 2022;192:762–770. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2022.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q., Guo H., Chou D.W., Berndt A., Sundberg J.P., Uitto J. Mutant Enpp1asj mice as a model for generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013;6:1227–1235. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomashvili K.A., Narisawa S., Millán J.L., O'Neill W.C. Vascular calcification is dependent on plasma levels of pyrophosphate. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitschke Y., Yan Y., Buers I., Kintziger K., Askew K., Rutsch F. ENPP1-Fc prevents neointima formation in generalized arterial calcification of infancy through the generation of AMP. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018;50:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0163-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boraldi F., Annovi G., Bartolomeo A., Quaglino D. Fibroblasts from patients affected by Pseudoxanthoma elasticum exhibit an altered PPi metabolism and are more responsive to pro-calcifying stimuli. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014;74:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabisch-Ruthe M., Kuzaj P., Götting C., Knabbe C., Hendig D. Pyrophosphates as a major inhibitor of matrix calcification in Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014;75:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomozi V., Brampton C., van de Wetering K., Zoll J., Calio B., Pham K., Owens J.B., Marh J., Moisyadi S., Váradi A., et al. Pyrophosphate Supplementation Prevents Chronic and Acute Calcification in ABCC6-Deficient Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2017;187:1258–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao J., Kingman J., Sundberg J.P., Uitto J., Li Q. Plasma PPi Deficiency Is the Major, but Not the Exclusive, Cause of Ectopic Mineralization in an Abcc6(-/-) Mouse Model of PXE. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2017;137:2336–2343. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Z., O'Brien K., Howe J., Sullivan C., Schrier D., Lynch A., Jungles S., Sabbagh Y., Thompson D. INZ-701 Prevents Ectopic Tissue Calcification and Restores Bone Architecture and Growth in ENPP1-Deficient Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021;36:1594–1604. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs I.J., Cheng Z., Ralph D., O'Brien K., Flaman L., Howe J., Thompson D., Uitto J., Li Q., Sabbagh Y. INZ-701, a recombinant ENPP1 enzyme, prevents ectopic calcification in an Abcc6(-/-) mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Exp. Dermatol. 2022;31:1095–1101. doi: 10.1111/exd.14587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan T., Sinkevicius K.W., Vong S., Avakian A., Leavitt M.C., Malanson H., Marozsan A., Askew K.L. ENPP1 enzyme replacement therapy improves blood pressure and cardiovascular function in a mouse model of generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018;11 doi: 10.1242/dmm.035691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira C.R., Kavanagh D., Oheim R., Zimmerman K., Stürznickel J., Li X., Stabach P., Rettig R.L., Calderone L., MacKichan C., et al. Response of the ENPP1-Deficient Skeletal Phenotype to Oral Phosphate Supplementation and/or Enzyme Replacement Therapy: Comparative Studies in Humans and Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021;36:942–955. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stabach P.R., Zimmerman K., Adame A., Kavanagh D., Saeui C.T., Agatemor C., Gray S., Cao W., De La Cruz E.M., Yarema K.J., Braddock D.T. Improving the Pharmacodynamics and In Vivo Activity of ENPP1-Fc Through Protein and Glycosylation Engineering. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021;14:362–372. doi: 10.1111/cts.12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang J., Snook A.E., Uitto J., Li Q. Adenovirus-Mediated ABCC6 Gene Therapy for Heritable Ectopic Mineralization Disorders. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2019;139:1254–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klement J.F., Matsuzaki Y., Jiang Q.J., Terlizzi J., Choi H.Y., Fujimoto N., Li K., Pulkkinen L., Birk D.E., Sundberg J.P., Uitto J. Targeted ablation of the abcc6 gene results in ectopic mineralization of connective tissues. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8299–8310. doi: 10.1128/mcb.25.18.8299-8310.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Q., Uitto J. Restricting dietary magnesium accelerates ectopic connective tissue mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Abcc6(-/-) ) Exp. Dermatol. 2012;21:694–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albright R.A., Stabach P., Cao W., Kavanagh D., Mullen I., Braddock A.A., Covo M.S., Tehan M., Yang G., Cheng Z., et al. ENPP1-Fc prevents mortality and vascular calcifications in rodent model of generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Nat. Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauffenstein G., Martin L., Le Saux O. The Purinergic Nature of Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum. Biology (Basel) 2024;13 doi: 10.3390/biology13020074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weng Y., Ishino T., Sievers A., Talukdar S., Chabot J.R., Tam A., Duan W., Kerns K., Sousa E., He T., et al. Glyco-engineered Long Acting FGF21 Variant with Optimal Pharmaceutical and Pharmacokinetic Properties to Enable Weekly to Twice Monthly Subcutaneous Dosing. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4241. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22456-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang J., Ralph D., Boraldi F., Quaglino D., Uitto J., Li Q. Inhibition of the DNA Damage Response Attenuates Ectopic Calcification in Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2022;142:2140–2148.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2022.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansen S., Perrakis A., Ulens C., Winkler C., Andries M., Joosten R.P., Van Acker M., Luyten F.P., Moolenaar W.H., Bollen M. Structure of NPP1, an ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase involved in tissue calcification. Structure. 2012;20:1948–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs I.J., Li Q. Novel Treatments for PXE: Targeting the Systemic and Local Drivers of Ectopic Calcification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms242015041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.