Abstract

We describe the case of a 36-year-old woman with a past medical history of low grade right frontal lobe glioma and focal epilepsy presenting with subacute, progressive, multifocal myoclonus and neck and back pain. Unlike her typical seizures, the myoclonus exhibited a distinct semiology, involving both positive and negative muscle jerks affecting multiple limb muscles while sparing the face. In addition, neurological examination revealed low-amplitude, arrhythmic movements of the hands and fingers, resembling minipolymyoclonus. There were no other neurological exam findings, including mental status changes, extrapyramidal signs or signs of myelopathy. Brain and spine MRI indicated leptomeningeal and spinal “drop” enhancing lesions, suggesting likely malignant evolution of the glioma. EEG ruled out a cortical origin of the myoclonus. Pharmacological trials with benzodiazepines and other antiepileptic medications were ineffective. The patient’s myoclonus was most likely spinal segmental in origin from meningeal spread of glioma. The spinal roots or anterior horns of the spinal cord may have represented a focus of hyperexcitability responsible for generating minipolymyoclonus. Our case expands the etiological spectrum of non-epileptic myoclonus and minipolymyoclonus to encompass meningeal carcinomatosis and drop metastases from glioma. These cases may occur even without overt signs of myelopathy. Recognizing such presentations holds significance due to the poor prognosis associated with meningeal spread of glioma and the limited response of non-epileptic myoclonus to symptomatic treatments.

Keywords: leptomeningeal, spinal segmental myoclonus, high grade glioma, polyminimyoclonus

Case Description

A 36-year-old woman with a history of WHO grade II right frontal lobe astrocytoma presented with progressively worsening myoclonus and neck and back pain over the course of 1 month.

The patient had a history of multiple tumor resections due to in situ re-growth of the astrocytoma, with the most recent resection occurring 3 years prior. At the time of her current presentation, she was receiving chemotherapy (temozolomide), and the tumor was clinically and radiologically stable. The tumor was symptomatic with mild left sided weakness and frontal lobe epilepsy. Her seizures had been controlled on multiple antiepileptic medications (clobazam, levetiracetam, and lacosamide), with the last typical seizure occurring 1 year prior. No recent changes in antiepileptic or other medications nor systemic symptoms had preceded the development of the myoclonus.

The patient’s current presentation included intermittent myoclonic jerks (Video 1) distinct from her typical seizures, along with neck and lower back pain radiating to the bilateral lower extremities, which limited her ability to ambulate.

Neurological examination revealed known upper motor neuron weakness on the left side, and multifocal myoclonus, both positive and negative. Low-amplitude, arrhythmic movements of the hands and fingers, resembling minipolymyoclonus, were noted both while her arms maintained a posture and during movement (Video 1). Additionally, there was neck stiffness and tenderness on palpation in the cervical and lower thoracic spine. Otherwise, her examination was unremarkable, with no evident cognitive changes, extrapyramidal signs or signs of myelopathy.

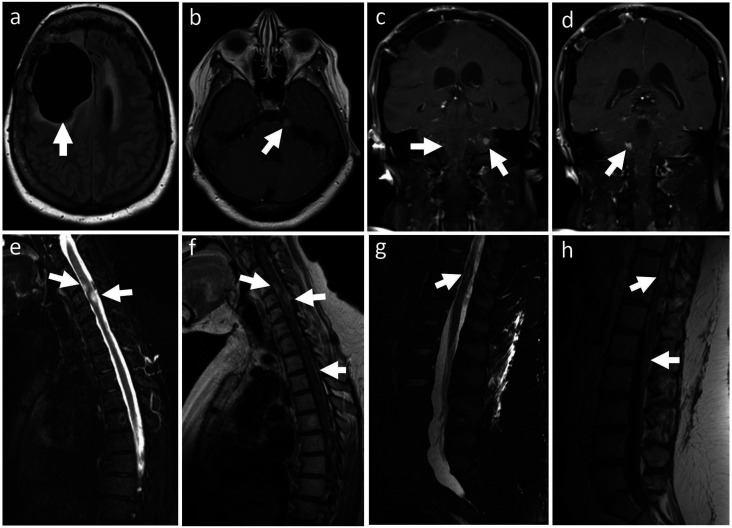

Diagnostic laboratory studies for common causes of toxic/metabolic encephalopathy yielded unremarkable results. This included normal renal and liver panels, magnesium, phosphate, calcium, ammonia, venous blood gas, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, urine analysis, urine toxicology, and chest X-ray. Brain MRI showed a stable resection cavity in the right frontal lobe, with no evidence of local disease progression (Figure 1(a)). However, there was a contrast-enhancing dural-based nodule in the left cerebello-pontine angle (Figure 1(b)), extensive leptomeningeal enhancement, both diffuse and nodular, in the posterior fossa (Figure 1(c) and (d)), spinal cord and cauda equina, as well as intraparenchymal nodules within the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure 1(e-h)).

Figure 1.

Brain (a-d) and spine MRI (e-h). FLAIR imaging showing (arrow) the resection cavity residual of right frontal lobe astrocytoma (a). Post-gadolinium T1 sequences showing enhancement of a dural-based nodule in the left ponto-cerebellar angle (b) and leptomeningeal enhancement, both diffuse and nodular, in the posterior fossa (c, d). STIR T2-hyperintense (e, g) and contrast enhancing (f, h) nodular lesions, apparently infiltrating the spinal cord, were noted at C4, C5 and T10. Cord edema is noted particularly at C5. Diffuse and nodular leptomeningeal enhancement involved the whole spinal cord, including the cauda equina (h).

Additional workup included a CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis with and without contrast that ruled out systemic metastases, and a negative serum paraneoplastic panel to rule out an atypical (opsoclonus was not observed) presentation of opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome as well as anti-CASPR2-associated paraneoplastic syndrome. The patient declined a lumbar puncture, and CSF cytology and paraneoplastic testing could not be completed. The overall clinical-radiological picture, however, pointed towards meningeal dissemination (dural and leptomeningeal) and spinal “drop” metastases from likely malignant evolution of a previously lower-grade astrocytoma. Continuous video-EEG, which included jerk-locked back-averaging analysis, captured multiple myoclonic jerks without any cortical electrical correlation. Surface or needle electrode recording of the myoclonus was deferred given patient’s pain level. The myoclonus did not respond to benzodiazepines and trials with additional antiepileptics (valproic acid, zonisamide). The patient was ultimately referred to hospice care and died 3 months later.

Discussion

Myoclonus is a sudden, brief, involuntary, and jerky movement caused by muscle contraction (positive myoclonus) or inhibition of ongoing muscle activity (negative myoclonus or asterixis). 1 It can be classified by multiple criteria, including etiology (physiologic, essential, epileptic or symptomatic), semiology (focal, multifocal, or generalized; spontaneous or reflex; positive or negative; rest, posture, or action), and pathophysiology – i.e., presumed site of origin - (cortical, cortical-subcortical, subcortical-nonsegmental, segmental, and peripheral).1,2 The latter classification is the most practical as it guides treatment strategies, with cortical and cortical-subcortical myoclonus being more frequently responsive to antiepileptic medications, and spinal myoclonus being typically refractory. 1

Non-epileptic myoclonus as a presenting sign of (lepto)meningeal carcinomatosis is rare, with few prior literature reports.3,4 This includes a case of leptomeningeal dissemination of glioblastoma, where the patient exhibited negative myoclonus, likely as an expression of diffuse encephalopathy. 3 The mechanism underlying myoclonus in the context of encephalopathy is not fully understood and likely multifaceted, involving dysfunction within the diencephalic-ponto-reticular formation, disruption of thalamocortical connections, or abnormal excitability in cortical regions responsible for sensorimotor integration. 5 This results in altered control of muscle tone and posture, hence the typical negative semiology of the myoclonus. However, our patient exhibited normal mental status, both positive and negative myoclonus, and no abnormalities in lab work or new medications that would suggest an underlying encephalopathy. Jung et al. 4 reported a case of hemidystonia and positive myoclonus in a patient with leptomeningeal metastasis from gastric adenocarcinoma. The pathophysiology was attributed to abnormal functioning of the cortico-striato-pallido-thalamo-cortical loop in the setting of relatively focal cortical involvement. In our patient, however, there were no extrapyramidal findings to suggest such mechanisms, and there was no new cortical involvement on brain imaging.

The most plausible pathophysiological explanation for our case was a spinal segmental myoclonus.2,6 This refers to myoclonic jerks of muscle groups supplied by 1 or more contiguous segments (i.e., myomeres) in the spinal cord. Spinal myoclonus is most commonly symptomatic of structural disorders affecting the spinal cord, including trauma, spondylosis, tumor, infection, inflammation/demyelination, ischemia, or radiation.1,2 Uncommon reports include cases secondary to intrathecal opioid infusion 7 and pregnancy. 8

Hypotheses for the pathophysiology of spinal myoclonus include dysfunction of dorsal horn inhibitory interneurons (GABA-ergic or glycinergic), abnormal hyperactivity of anterior horn alpha motoneurons, or aberrant re-excitation of sensory or motor axons within the spinal roots.2,9 In our case, the presence of multilevel root infiltration from leptomeningeal disease may have acted as a multifocal generator of the myoclonus. This mechanism has been reported in myoclonus secondary to multiple sclerosis, where demyelinating plaques can involve root entry/exit zones at multiple contiguous spinal segments. 10 The involvement of spinal roots in our patient was supported clinically by spine tenderness and radicular pain.

Interruption of inhibitory descending pathways controlling motoneuron firing may represent an alternative mechanism of segmental myoclonus.2,9 In this context, the intrinsic cord lesions noted on MRI could be relevant pathophysiologically. However, this would not explain the apparent clinical involvement of multiple myomeres, including the lumbar levels associated with leg/foot jerking. Moreover, despite imaging evidence of intrinsic spinal cord lesions, there were no clinical signs indicative of myelopathy.

Propriospinal myoclonus is an additional variant of spinal myoclonus described in the literature, characterized by extensive contraction of axial and trunk muscles via slowly conducting propriospinal pathways. 11 However, unlike our patient, cases of propriospinal myoclonus typically manifest a discernible cranio-caudal spread of the jerks. 11

Minipolymyoclonus, also known as polyminimyoclonus, is a hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by intermittent, low-amplitude, arrhythmic movements of the hands and fingers, described as “just sufficient to produce visible and palpable movements of the joints”. 12 It is typically observed when the patient maintains a posture (such as outstretched arms) or during movement, particularly in the initial phase. The terminology and underlying pathophysiology are subjects of debate, as minipolymyoclonus has been reported in a variety of neurological disorders affecting both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). 12 In CNS-related diseases, the pathophysiology may be aligned with that of myoclonus, positioning minipolymyoclonus as a distinct semiological variant. 12 In other conditions, including PNS disorders, it has been linked to anterior horn cell disease (e.g., ALS, SMA) or peripheral nerve hyperexcitability (e.g., anti-CASPR2-associated paraneoplastic syndrome), where it may represent an exaggerated form of fasciculations. 12 Although rare, an association with myopathy has also been documented, particularly in congenital myopathies (e.g., congenital nemaline myopathy), where it could be attributed to concurrent neurogenic changes or may present as a nonspecific finding. 12 In our case, the likely focus of hyperexcitability generating minipolymyoclonus would be the spinal roots or anterior horns of the spinal cord. This would be consistent with the proposed pathophysiology of the concurrent multisegmental myoclonus.

Finally, our case highlights how leptomeningeal spread of high-grade glioma is likely underdiagnosed, possibly due to low sensitivity of diagnostic tests and the occurrence of asymptomatic cases, while postmortem studies show a frequency as high as 25%. 13 Drop metastases, which indicate metastatic lesions of the spinal cord from a primary brain tumor, are an uncommon complication of glioma, but, similarly, likely expression of leptomeningeal spread. 14 Their occurrence is mainly related to a prior history of tumor resection, similar to our patient.13,14 Identification of meningeal and spinal metastasis from glioma carries a fatal prognosis, with a median survival of 4.7 months, and limited treatment options.13,14

Some limitations of our study must be acknowledged. Due to the patient’s level of pain, we were unable to perform an EMG, which could have better characterized the myoclonus and assessed for signs of PNS involvement, including root, peripheral nerve, or muscle. Additionally, the lack of an LP prevented pathological confirmation of leptomeningeal disease spread, although clinical and radiological findings strongly supported this diagnosis. For the same reason, a paraneoplastic panel in the CSF was unavailable. This is relevant considering that anti-CASPR2-associated syndrome could present similar to our case. While testing both CSF and serum for paraneoplastic antibodies enhances diagnostic sensitivity, it is worth noting that serum analysis may be more sensitive for anti-CASPR2 antibodies, and in this case, serum testing was negative. 15

In summary, our case expands the etiological spectrum of non-epileptic myoclonus as well as minipolymyoclonus to encompass meningeal carcinomatosis and drop metastases originating from glioma. Spinal segmental physiology may occur even without overt signs of myelopathy. The spinal roots or anterior horns of the spinal cord may represent a focus of hyperexcitability responsible for generating minipolymyoclonus. The recognition of these cases impacts treatment strategies, since benzodiazepines and antiepileptic medications, which are usually effective for cortical or cortical-subcortical myoclonus, have limited benefit. In addition, it may provide a clinical clue for the early diagnosis of spinal meningeal spread, informing about an invariably poor prognosis.

Supplemental Material

Video 1. Semiology. Myoclonic jerks were both positive and negative and involved multifocal limb muscles, in distal and proximal locations, without a clear cranial or caudal spread. The cranial district was spared. Movements occurred at rest and were exacerbated by action and posture. Additionally, low-amplitude, arrhythmic movements of the hands and fingers, resembling minipolymyoclonus, were observed both with posture and during movement. Myoclonus was persistent during sleep.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was not supported by any funding. Dr Taga is supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) through an administrative supplement to award R25NS065729. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views the National Institutes of Health.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

The patient discussed in this article and their surrogate was shown the final version of the manuscript and consented to its publication.

ORCID iDs

Arens Taga https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7059-3604

Kemar Green https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1112-7325

References

- 1.Kojovic M, Cordivari C, Bhatia K. Myoclonic disorders: a practical approach for diagnosis and treatment. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4(1):47-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibasaki H. Neurophysiological classification of myoclonus. Neurophysiol Clin. 2006;36(5-6):267-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begemann M, Tsiouris AJ, Malkin MG. Leptomeningeal and ependymal invasion by glioblastoma multiforme. Neurology. 2004;63(3):E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung HJ, Choi SM, Kim BC. Hemidystonia as an initial manifestation of leptomeningeal metastasis. J Mov Disord. 2009;2(2):82-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rissardo JP, Muhammad S, Yatakarla V, Vora NM, Paras P, Caprara ALF. Flapping tremor: unraveling asterixis-a narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(3):362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massimi L, Battaglia D, Paternoster G, Martinelli D, Sturiale C, Di Rocco C. Segmental spinal myoclonus and metastatic cervical ganglioglioma: an unusual association. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(3):365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiratori T, Hotta K, Satoh M. Spinal myoclonus following neuraxial anesthesia: a literature review. J Anesth. 2019;33:140-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taga A, Florindo I, Kiener A, Frusca T, Pavesi G. Spinal segmental myoclonus resembling “belly dance” in a pregnant woman. Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(11):2248-2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazzaro V, Restuccia D, Nardone R, et al. Changes in spinal cord excitability in a patient with rhythmic segmental myoclonus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1996;61:641-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alroughani RA, Ahmed SF, Khan RA, Al-Hashel JY. Spinal segmental myoclonus as an unusual presentation of multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roze E, Bounolleau P, Ducreux D, et al. Propriospinal myoclonus revisited: clinical, neurophysiologic, and neuroradiologic findings. Neurology. 2009;72(15):1301-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganguly J, Chai JR, Jog M. Minipolymyoclonus: a critical appraisal. J Mov Disord. 2021;14(2):114-118. doi: 10.14802/jmd.20166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandel JJ, Yust-Katz S, Cachia D, et al. Leptomeningeal dissemination in glioblastoma; an inspection of risk factors, treatment, and outcomes at a single institution. J Neuro Oncol. 2014;120:597-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibanda Z, Farahani N, Ogbonnaya E, Albanese E. Glioblastoma multiforme: a rare case of spinal drop metastasis. World Neurosurg. 2020;144:24-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joubert B, Saint-Martin M, Noraz N, et al. Characterization of a subtype of autoimmune encephalitis with anti-contactin-associated protein-like 2 antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid, prominent limbic symptoms, and seizures. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(9):1115-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1. Semiology. Myoclonic jerks were both positive and negative and involved multifocal limb muscles, in distal and proximal locations, without a clear cranial or caudal spread. The cranial district was spared. Movements occurred at rest and were exacerbated by action and posture. Additionally, low-amplitude, arrhythmic movements of the hands and fingers, resembling minipolymyoclonus, were observed both with posture and during movement. Myoclonus was persistent during sleep.