Abstract

Objective: We aimed to explore the efficacy and safety of Selinexor combined bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (XVRd) protocol in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease. Methods: This is a single-arm, open, observational clinical study. For induction/consolidation(21-day cycles), patients received 8 cycles of XVRd protocol. In maintenance (28-day cycles), patients received XR (Selinexor + Lenalidomide) at least 2 years until disease progression, death or withdrawal. The primary endpoints were overall response rates and minimal residual disease negative rates. Results: The median age of the 10 patients was 62 (range 55–81) years. R-ISS stage 3 was present in 2 (20%) patients. 3 patients had high risk cytogenetic and 1 patient with plasma cell leukocyte. According to IMWG criteria, the ORR of 10 patients with NDMM was 100%, including 2 stringent complete response (sCR), 2 complete remission (CR), 4 very good partial response (VGPR) and 2 partial response (PR). Median progression-free survival and overall survival were not achieved. The most common grade 3–4 treatment-emergent adverse events (occurring in 10% of patients) were thrombocytopenia. The most common non-hematological adverse events were grade 1 or 2, including nausea (30%), fatigue (40%), and anorexia (20%). Overall, the severe toxicities were manageable. Conclusion: The XVRd regimen had good efficacy and safety in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Selinexor, Extramedullary disease

Subject terms: Cancer, Medical research, Oncology

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant proliferation of clonal plasma cells characterized by hypercalcemia, anemia, renal insufficiency, and osteolytic bone lesions, which accounts for 1% of all cancers and approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies1. In most MM patients, plasma cell proliferation is confined to the bone marrow cavity, but a subset of patients may grow outside the bone marrow, called multiple myeloma extramedullary infiltration (EMM). EMM can arise from skeletal focal lesions, which disrupt the cortical bone and grow as extra-bone masses, and is referred to as extramedullary bone related (EMB), or derive from hematogenous spread as manifestation in soft tissues, and is called Extramedullary extraosseous(EME)2. Incidence of EMM at diagnosis ranges between 7% and 18%, while later in the course of the disease this increases to 30-50%3. In recent years, with the prolongation of the survival of MM patients, the updating of examination methods and the attention of clinicians, the incidence of EMM has gradually increased. EMM is an independent poor prognostic factor of MM. High-risk (HR) cytogenetics are significantly enriched in MM with EMM. Currently, MM cannot be cured, and the main treatment options include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and autologous stem cell transplantation(ASCT). For common newly diagnosed MM patients, domestic and foreign guidelines usually recommend bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRd) protocol as the first-line treatment option. However, patients with EMM are highly invasive, and the VRd regimen is difficult to achieve ideal therapeutic effects. Usually, the treatment regimen for high-risk MM is referred to, which is mainly based on proteasome inhibitors (PIs) and immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs). ASCT still occupies an important position in the treatment of EMM. At the same time, various new drugs bring hope to the treatment of EMM. To date, the treatment of EMM remains very challenging and prospective clinical studies are urgently needed to explore optimal options.

Selinexor is a first-in-class Selective Inhibitor of Nuclear Export (SINE) compound that selectively binds and inactivates exportin-1(XPO1). Its unique mechanism provides the basis for its application in patients with extramedullary disease. The results of the BENCH study initially suggested that Selinexor is more effective than other regimens in MM patients with HR cytogenetics. After one course of Selinexor combined bortezomib and dexamethasone treatment, the volume of a patient with a soft tissue mass around the eyeball shrank by nearly 90%, suggesting that Selinexor may have a special effect on patients with extramedullary plasmacytoma. In the STORM study (NCT02343042), 122 patients with penta-exposed, triple-class refractory multiple myeloma were enrolled to receive Selinexor combined with low-dose dexamethasone. 27 patients were diagnosed with EMM at baseline. Follow-up evaluation of plasma cell tumor was performed in 16 cases, and complete disappearance or shrinkage of extramedullary lesions was observed in 9 cases4. Currently, data on the treatment outcomes of EMM mainly come from retrospective studies, and prospective studies are needed to accurately evaluate the efficacy and safety. Based on this, we conducted this study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Selinexor combined with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (XVRd) protocol as first-line treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients with EMM.

Methods

Patients

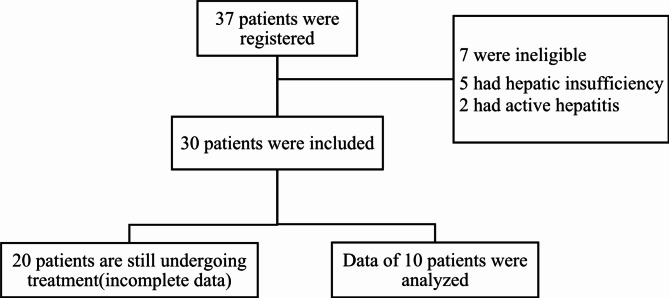

This open, single-arm prospective study included 10 patients with NDMM with EMM from August 2022 to December 2023 in 3 hospitals (Fig. 1). This trial was registered with Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, number ChiCTR2200062860. All patients received XVRd regimen. The diagnosis of extramedullary plasmacytoma was confirmed by pathological biopsy in all patients. Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years of NDMM with EMM, meet the updated criteria for the diagnosis of MM in International Myeloma Working Group(IMWG) and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group(ECOG) performance status of 0–21. Exclusion criteria: ① patients with active hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and other acquired and congenital immunodeficiency diseases; ② patients with grade 2 or more terminal neuropathy or neuralgia; ③ patients with serious thrombotic events prior to treatment; ④ patients with hepatic insufficiency (ALT and AST ≥ 2 times the upper limit of normal values).

Fig. 1.

Enrollment and Follow-up.

Laboratory tests perfected in all patients before treatment included complete blood count, biochemical tests (serum albumin, globulin, total protein, calcium, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine), β2-microglobulin, serum protein electrophoresis, immunofixation electrophoresis, serum free light chains, morphological analysis of peripheral blood, bone marrow cytomorphometry, bone marrow biopsy, immunophenotyping, and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH). Other tests included electrocardiogram (ECG), cardiac ultrasound, lung computed tomography (CT), and vertebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients with at least one of the following aberrations were considered as high-risk cytogenetics: del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20), p53 mutation, gain(1q). All patients were evaluated for EMM based on imaging and lesion size was measured before treatment.

Treatment, response, and outcome

For induction/consolidation(21-day cycles), patients received 8 cycles of XVRd (Selinexor 60 mg PO weekly, Bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 SC days1, 4, 8, 11, Lenalidomide 25 mg PO days 1–14, and Dexamethasone 40 mg PO weekly). Patients suitable for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) received 4 courses of induction therapy and ASCT after efficacy was assessed to be in partial remission and above, after which they continued XVRd consolidation therapy for 4 courses and entered maintenance therapy; patients not suitable for ASCT were treated with the XVRd regimen for 8 courses, after which they entered maintenance therapy. In maintenance (28-day cycles), patients received XR (Selinexor + Lenalidomide) at least 2 years until disease progression, death or withdrawal.

The primary endpoints were overall response rates (ORR) and minimal residual disease (MRD) negative rates by end of induction. The secondary endpoints were complete response (CR), progression free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and toxicity. The efficacy of induction therapy was evaluated every 2 courses. All patients were evaluated as progression disease (PD), stable disease (SD), partial response (PR), very good partial response (VGPR), CR, and stringent complete response (sCR) according to IMWG criteria5. ORR = sCR + CR + VGPR + PR. The level of MRD was detected by 8-color flow cytometry after induction therapy. After treatment, the efficacy of EMM was evaluated according to imaging, and the lesion size was measured.

Adverse events (AE) during Selinexor containing treatment were characterized according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.06. Adjust drug dosage according to AE.

Patient survival was obtained from telephone follow-up and access to outpatient or inpatient records. Follow-up ended on April 30, 2024, with a median follow-up of 15 (5–18) months. OS was defined as the time from initiation of treatment with Selinexor until death or termination of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Using descriptive statistics, we summarized patients’ characteristics as absolute number and percentage, and if not otherwise stated as median and range. The survival analysis was performed with Kaplan–Meier method. These analyses were performed with “IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 25.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA)”.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

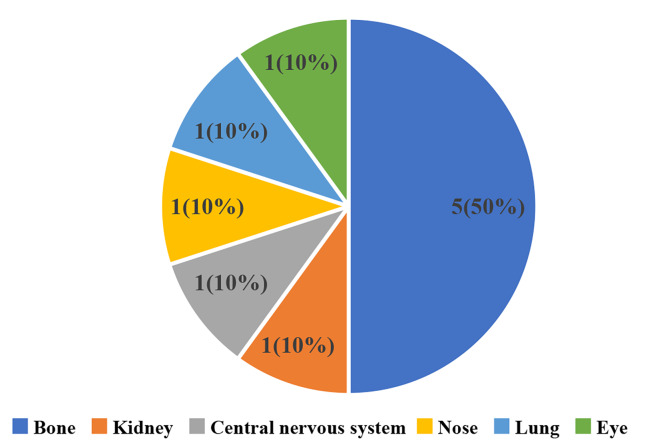

10 patients with previously untreated NDMM were included in the study. Five of the patients were female and five were male. Median age was 62 (range 55–81) years. Patients with an ECOG score of less than or equal to one comprised 70% of the cases. R-ISS stage 3 was present in 2 (20%) patients (Table 1). Among all patients, five were IgG, one was IgD, one was IgA, and three were light chain. 3 patients had high-risk cytogenetic from bone marrow biopsy, including 1q21 gain(n = 3, 30%), one of which was combined with 17p deletion (n = 1, 10%). When the patients were examined according to the EMM involvement regions, five patients had cortical bone, one patient had central nervous system, one patient had kidney, one patient had sinus, one patient had eye, and one patient had soft tissue of chest (Fig. 2). Patients’characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristic.

| n | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 5 | 50 | ||

| Female | 5 | 50 | ||

| ECOG Performance Status | ||||

| 0 | 3 | 30 | ||

| 1 | 4 | 40 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 30 | ||

| Type of myeloma | ||||

| IgG | 5 | 50 | ||

| IgD | 1 | 10 | ||

| IgA | 1 | 10 | ||

| Light chain | 3 | 30 | ||

| R-ISS stage at initial diagnosis | ||||

| I | 1 | 10 | ||

| II | 7 | 70 | ||

| III | 2 | 20 | ||

| Cytogenetics | ||||

| Normal | 7 | 70 | ||

| Del 17p | 1 | 10 | ||

| 1q21 gain | 3 | 30 | ||

| Del 13q | 1 | 10 | ||

| Serum beta-2 microglobulin level | ||||

| <3.5 mg/liter | 3 | 30 | ||

| 3.5-5.5 mg/liter | 5 | 50 | ||

| >5.5 mg/liter | 2 | 20 | ||

| Response to Therapy | ||||

| sCR | 2 | 20 | ||

| CR | 2 | 20 | ||

| VGPR | 4 | 40 | ||

| PR | 2 | 20 | ||

Fig. 2.

EMM Involvement region.

Treatment and response to therapy

All patients completed at least 3 courses of treatment, and the median number of courses was 6 (3–15). According to IMWG criteria, the ORR of 10 patients with NDMM was 100%, including 2 sCR, 2 CR, 4 VGPR and 2 PR. Median time to first response in patients with a partial response or better was 1 months (1–2). Among the 10 patients, only 1 patient with plasmacytic leukemia died due to disease progression, and 1 patient changed to other programs due to disease progression after 6 courses. 1 patient evaluated with sCR at the end of the induction period was evaluated with MRD negativity after autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Of the 10 patients, the extramedullary lesions disappeared completely in 4 cases after induction therapy, and the chest soft tissue mass of 1 patient disappeared completely after 2 courses of treatment, while shrinkage of extramedullary lesions was observed in the other 6 patients. Median PFS and OS times were not achieved, one-year PFS rate was 60% and one-year OS rate was 90.0%. The size of extramedullary lesions before and after treatment is shown in Table 2. This results established that XVRd regimen has a prospective response for MM with EMM.

Table 2.

Complete data of 10 patients.

| Pat | Age | Gender | Type | DS stage | ISS stage | RISS stage | ECOG score | FISH | Extramedullary involvement | Response | AEs | PFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | Female | IgDλ | IIIA | III | III | 2 | 1q21+ | Kidney | VGPR | Nausea/Anorexia/ Myelosuppression | 4 | |

| 2 | 61 | Male | IgGκ | IIIA | III | II | 1 | Normal | Rib | VGPR | Nausea/Vomiting/Fatigue | 18 | |

| 3 | 66 | Male | IgGκ | IIIA | II | II | 0 | Normal | Thoracic | sCR | Fever/ Myelosuppression | 18 | |

| 4 | 59 | Male | κ | IIIA | II | II | 0 | Normal | Thoracic | CR | Fatigue | 16 | |

| 5 | 55 | Female | IgGλ | IIIA | II | II | 0 | 1q21+/13q- | Humerus/femur | sCR | Fatigue/Myelosuppression | 15 | |

| 6 | 56 | Male | IgAκ | IIIA | I | I | 1 | Normal | Nasal cavity | VGPR | Nausea/Anorexia | 7 | |

| 7 | 69 | Female | IgGκ | IIIA | II | II | 2 | Normal | CNS | PR | Fatigue | 6 | |

| 8 | 68 | Female | IgGλ | IIIA | II | II | 2 | Normal | Lung | CR | Celialgia/Myelosuppression | 18 | |

| 9 | 81 | Female | κ | IIIA | III | III | 1 | 17p-/1q21+ | Eye | PR | Thrombocytopenia | 9 | |

| 10 | 63 | Male | λ | IIA | II | II | 1 | Normal | Ilium | VGPR | Myelosuppression | 15 |

Pat—Patient; DS—The Multiple Myeloma Durie-Salmon Staging System; ISS—The Multiple Myeloma International Staging System; RISS—Revised International Staging System; VGPR—very good partial response; PR—partial response; ECOG—Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FISH—Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization; CNS—central nervous system; AEs—Adverse Events.

Adverse events (AEs)

All patients were given 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonist (palonosetron 0.25 mg or equivalent) and olanzapine to prevent nausea. The most common grade 3–4 haematological AEs was thrombocytopenia (n=1, 10%), and there were no grade 3–4 non-haematological AEs. The most common grade 1–2 haematological AEs were neutropenia (n=5, 50%), thrombocytopenia ((n=5, 50%) and anaemia (n=5, 50%), while non-haematological AEs were mainly gastrointestinal reactions, including nausea in 3(30%)cases and vomiting in 1(10%)cases, anorexia in 2(20%)cases, and abdominal pain in 1(10%)case, all of which were grade 1–2, and were improved after the administration of supportive treatment with antiemetic, gastric mucous membrane protective agents, and gastrointestinal motility-promoting drugs. Other AEs included fatigue in 4 (40%)cases and fever in 1 (10%)case, all of which were grade 1–2. Overall, the severe toxicities were manageable. The adverse events for all patients are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Compare the lesion size before and after treatment.

| Patients | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre-treatment(cm) | 9.4*8.8 | 3.3*4.9 | 3.1*3.7 | 2.0*1.7 | 2.2*1.9 | 4.3*3.6 | 8.0*6.0 | 5.0*4.0 | 3.0*4.0 | 5.0*7.0 |

| post-treatment(cm) | 3.8*2.2 | 1.1*1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.7*0.8 | 3.3*2.5 | 0 | 1.1*1.8 | 1.6*2.0 |

Discussion

The treatment of MM combined with extramedullary plasmacytoma remains very challenging, with a lack of prospective study results and no targeted standard treatment protocols in clinical practice. Exportin 1 — the sole known nuclear exporter of tumor suppressor proteins, the glucocorticoid receptor, and oncoprotein messenger RNAs (mRNAs) — is overexpressed in myeloma and correlates with increased bone disease and shorter survival7,8. Selinexor is a potent, oral, selective inhibitor of nuclear export that binds to Cys528 in the cargo-binding pocket of XPO1, forcing the nuclear localization and functional activation of tumor suppressor proteins, trapping IκBα in the nucleus to suppress nuclear factor κB activity, and preventing oncoprotein mRNA translation9,10. In addition, SINE compound has synergistic effect with cytotoxic drugs, PIs and IMiDs11,12. The STORM study has preliminarily demonstrated the therapeutic activity of Selinexor in patients with EMM. At present, both domestic and international guidelines recommend VRd as first-line therapy for high-risk MM patients, but the efficacy of VRd for NDMM patients with EMM is not ideal.

The results of this study showed that the median number of effective courses of XVRd induction therapy was one course, and the ORR reached 100%, indicating that the XVRd regimen may offer a promising therapeutic approach for this difficult-to-treat condition. 2 of 10 patients underwent ASCT, and 1 patient evaluated with sCR at the end of the induction period was evaluated as MRD negative after transplantation. Therefore, Selinexor may achieve deep remission in NDMM patients with EMM. Patients eligible for transplantation may have further sequential ASCT to prolong progression-free survival. Complete disappearance or shrinkage of extramedullary lesions was observed in 10 cases. One patient with central nervous system involvement had an extramedullary mass that decreased by > 50% in volume after 2 courses of treatment, and one patient with a 5*4 cm chest soft tissue mass completely disappeared after 2 courses of treatment. Combined with previous animal experiments and many clinical case reports, it is suggested that Selinexor may have potential therapeutic effects on patients with central nervous system involvement. Among the 3 patients with high risk cytogenetics, 1 patient complicated with plasmacytic leukemia died after 3 courses of treatment. Combined with the results of the STORM study, it shows that Selinexor may have clinical benefits for patients with high-risk cytogenetics, but the efficacy is still unsatisfactory for patients with plasma cell leukemia.

The protocol was safe and the AEs can be controlled, and no new AEs have been observed in this study. Hematological AEs were the most common AEs during the treatment, especially when used in combination with drugs with bone marrow suppressive effects such as IMiDs, more attention should be paid. The frequency and severity of AEs are similar to those observed in the STORM trial, and can be controlled by active prophylactic and supportive therapy, dose adjustments, and other measures, and are progressively better tolerated by patients as the duration of treatment increases. Most hematological AEs occur within the first 2 treatment cycles. Complete blood counts should be closely monitored, symptomatic treatments such as TPO agonists and platelet transfusion should be applied as soon as possible, and Selinexor can be reduced or discontinued if necessary. Only one patient had a grade ≥ 3 Thrombocytopenia. The most common non-hematological AEs in this study were nausea, anorexia, and fatigue, which were mostly grade 1–2. Prevention is more important than treatment. The study has limitations, such as a small sample size and short follow-up time, and larger randomized clinical trials are needed to verify these results. The single-arm design also limits the ability of studies to determine that the XVRd regimen is superior to other treatment options. In addition, the long-term safety of Selinexor remains to be seen.

Conclusions

The XVRd regimen had good efficacy and safety in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease. It is worthy of further study based on the preliminary efficacy results. Longer-term results still require more patients have been enrolled.

Author contributions

YJJ:Conduct research, collect data, analyze/interpret data, write papers; ZX and LXM:Conduct research and collect data; YCL, CXX, HLM and WHY:Screening cases and conduct research; ZYP: designed and supervised the trial, reviewed the data, reviewed and approved the paper.

Funding

This research was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation Research Project (Approval number: Z20J00076).

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors with permission of the institution.

Declarations

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the independent ethics committee of Qingdao Municipal Hospital (No. 2022Y042).

Patient consent

All patients provided written informed consent.

Clinical trial registration

ChiCTR2200062860.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rajkumar, S. V. et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol.15, e538–548. 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70442-5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sevcikova, S. et al. Extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma - controversies and future directions. Blood Rev.36, 32–39. 10.1016/j.blre.2019.04.002 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosiñol, L. et al. Expert review on soft-tissue plasmacytomas in multiple myeloma: definition, disease assessment and treatment considerations. Br. J. Haematol.194, 496–507. 10.1111/bjh.17338 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee, A. J. et al. Response to Therapy and the effectiveness of treatment with selinexor and dexamethasone in patients with Penta-exposed triple-class Refractory Myeloma who had plasmacytomas. Blood. 134, 5. 10.1182/blood-2019-129038 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar, S. et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol.17, e328–e346. 10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30206-6 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freites-Martinez, A., Santana, N., Arias-Santiago, S. & Viera, A. Using the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE - version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of adverse events of Anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 112, 90–92. 10.1016/j.ad.2019.05.009 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jardin, F. et al. Recurrent mutations of the exportin 1 gene (XPO1) and their impact on selective inhibitor of nuclear export compounds sensitivity in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol.91, 923–930. 10.1002/ajh.24451 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt, J. et al. Genome-wide studies in multiple myeloma identify XPO1/CRM1 as a critical target validated using the selective nuclear export inhibitor KPT-276. Leukemia. 27, 2357–2365. 10.1038/leu.2013.172 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benkova, K., Mihalyova, J., Hajek, R. & Jelinek, T. Selinexor, selective inhibitor of nuclear export: unselective bullet for blood cancers. Blood Rev.46, 100758. 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100758 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nachmias, B. & Schimmer, A. D. Targeting nuclear import and export in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 34, 2875–2886. 10.1038/s41375-020-0958-y (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner, J. G. et al. Treatment of acquired drug resistance in multiple myeloma by combination therapy with XPO1 and topoisomerase II inhibitors. J. Hematol. Oncol.9, 73. 10.1186/s13045-016-0304-z (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashyap, T. et al. Selinexor, a selective inhibitor of Nuclear Export (SINE) compound, acts through NF-κB deactivation and combines with proteasome inhibitors to synergistically induce tumor cell death. Oncotarget. 7, 78883–78895. 10.18632/oncotarget.12428 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors with permission of the institution.