Abstract

Objective

For emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease, future uncertainty is a critical issue during this pivotal stage of life, study and career development, as they encounter many unknown challenges and opportunities. However, to the best of our knowledge, only a few qualitative studies on how emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease cope with these uncertainties exist. This study aimed to investigate uncertainties associated with the future of emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease and explore coping strategies.

Design

A qualitative semistructured interview study with a phenomenological approach. Face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted, audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and subsequently analysed using the Colaizzi seven-step analysis method.

Setting

A tertiary hospital in eastern China.

Participants

Participants (n=14) were emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease recruited from a tertiary hospital in eastern China, using a purposeful sampling technique.

Results

Fourteen patients completed the interviews. Four themes were identified: uncertainties in educational and vocational planning, social and interpersonal relationships, mental and emotional health and disease management. Moreover, the participants emphasised the significance of timely patient education postdiagnosis and ensuring consistent medical guidance after discharge to minimise uncertainty and alleviate confusion. They also hoped to manage the disease through traditional Chinese medicine.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the various challenges encountered by emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease and the factors that may impact their experiences. Additionally, it suggests the need for healthcare providers to devise suitable support and intervention strategies to guide and establish stable management of the patients’ uncertain futures.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR2300071289.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Adult gastroenterology, Chronic Disease

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The study will provide healthcare providers with an in-depth understanding of the challenges and unmet needs faced by emerging adults (18–29) with inflammatory bowel disease.

The study also validates the potential of traditional Chinese medicine in managing emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease from patients’ perspectives.

Selection bias may have occurred, as individuals with remission or mild-to-moderate active disease and those interested in the research were more willing to complete the survey, which may have affected the validity of the results.

This was an exploratory study conducted at a tertiary hospital in eastern China, which may limit the generalisability of the results to other settings.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects the gastrointestinal tract and currently has no cure. The peak age of IBD onset ranges from 15 to 29 years during adolescence and young adulthood.1 IBD has emerged as a global health concern,2 with an exponential increase in its incidence in many parts of Asia, similar to that in Western countries.3 Notably, China has the highest prevalence of IBD in Asia.4 Consequently, the societal burden of IBD poses a considerable public health challenge in China.5

The concept of emerging adults (EA) was initially introduced by the American psychologist Arnett in 2000.6 EA typically spans the 18–29 age range and represents a crucial phase in the transition from adolescence to adulthood, during which individuals face numerous uncertainties and challenges regarding cognitive, emotional, physiological and social development trajectories.7 Research has demonstrated that EA management can assist individuals with chronic diseases by effectively addressing the numerous challenges encountered during this stage of life. This approach can enhance disease management behaviours and contribute to achieving favourable health management outcomes.8 9

Future uncertainty is a major concern for EA with IBD (EAI) as they encounter various unfamiliar challenges and opportunities. These challenges include a decline in learning abilities, stigma10 11 and limitations in occupational opportunities.12 13 Previous research indicated that implementing EA management yields specific outcomes in EAI.14 15 However, there are limited qualitative studies that use face-to-face interviews to delve into the experiences and responses of EAI to this uncertainty.16 17

As the duration of the disease increased, especially 6 months postdiagnosis, most patients gradually accepted the reality of their illness and began to reflect on and manage their disease independently.18 19 Therefore, this study aims to examine the uncertainties faced by EAI who have been diagnosed for at least 6 months in eastern China, the potential impact of these uncertainties on their future, and the strategies that these individuals use to cope with those uncertainties.

Material and methods

Registration, approval and participants’ consent

A descriptive qualitative study using a phenomenological research approach was conducted between 1 January and 31 July 2023. Face-to-face semistructured interviews were used to collect data as part of an ongoing project which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the local hospital (approval no. 2023NL-004–02), and was registered with the China Clinical Trials Registry (www.chictr.org.cn, identifier: ChiCTR2300071289). All participants signed a paper version of the informed consent form before the interview.

Participants

Patients were recruited from a tertiary hospital in eastern China, using a purposeful sampling technique. The inclusion criteria were (1) diagnosis of IBD in accordance with the 2018 Chinese criteria,20 (2) age between 18 and 29 years, (3) disease duration≥6 months and (4) willingness to participate in the study. Patients with significant medical comorbidities (such as cancer) and developmental or intellectual disabilities were excluded from the study. Sampling was discontinued once thematic saturation was achieved. Sixteen patients were invited to participate in the interviews; however, two declined due to concerns expressed by the mother of one patient and the partner of the other, who were apprehensive about the potential negative emotions that might arise in the patients when recalling past experiences. Consequently, a total of 14 patients participated in the study.

Procedures

The interviews were conducted in a non-clinical setting within the hospital, with no one present except for the interviewer and the interviewee, in order to prevent disruptions and maintain confidentiality. The interviews were conducted by two nursing graduate students from the research team. Prior to the interviews, the interviewers familiarised themselves with the participants’ medical conditions, reiterated the purpose and significance of the study, and, with the participants’ consent, recorded the interviews in full. The participants were assured of complete anonymity and that strict confidentiality principles would be adhered to. An interview guide comprising open-ended questions was followed to encourage participants to discuss the impact of the disease on themselves and freely reflect on their experiences of self-management to cope with these effects. The questions covered aspects such as participants’ disease knowledge, attitudes and coping strategies, providing insights into their future uncertainties and coping needs (online supplemental file A). To ensure the efficacy of the interview guide, it was pilot tested on two individuals who represented the target group (although they were not part of the final sample), resulting in a few minor revisions. Following each interview, interview notes were promptly recorded to capture the details of the interactions, interview environments and participants’ body language. Additionally, telephonic follow-ups were conducted to address unclear audio recordings or uncertainties in the transcribed data. A total of 14 interviews were conducted; the mean duration of the interviews was 58 min, ranging from 46 to 94 min.

Data analysis

The interview recordings were transcribed using WPS Office within 24 hours of the interview, with the interviewees named P1–P14. The transcripts were manually checked for accuracy and revised accordingly, and supplemented with non-verbal information from the interview notes. The interviews were summarised in WPS Office to facilitate data storage and coding. The research team used the Colaizzi seven-step analysis to analyse the data,21 which involved the following processes: (1) comprehensively reading the interview materials to familiarise themselves with all the content provided by the participants; (2) identifying and extracting key statements related to the research content; (3) coding the ideas repeatedly mentioned by the respondents; (4) grouping relevant codes to form topic groups; (5) describing the original respondents’ statements; (6) identifying similar views, summarising them and elevating them into new topics and (7) verifying the results to ensure accuracy. In this study, data collection and analysis were conducted simultaneously to explore emerging themes from the remaining interviews. No code was predetermined or preset. The team used manual coding to encode the transcription data, marking key units, sentences and paragraphs. We continuously discussed and improved the prethreshold code. The main author developed an operational coding tree based on a preliminary review of the transcripts and applied it to the remaining transcripts. Two researchers independently completed the coding of the data and held regular coding review meetings. Any discrepancies were discussed within the research group, and a consensus was reached. The researchers examined the code in all interviews, adjusting and organising it to capture emerging patterns of meaning through an iterative process. During this process, the research team organised and refined recurring themes related to potential connections between the research questions and subjects, forming subthemes and themes. The research team consistently reviewed the interview transcripts and codes to ensure that the themes accurately reflected the participants’ descriptions of their experiences. All coauthors examined and provided feedback on the analysis and interpretation of the results. The study results were also shared with the participants for verification.

Rigour

The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was followed throughout the study (online supplemental file B).22 Three strategies were implemented to ensure the rigour of the study. First, researchers prioritised establishing strong relationships with the participants before conducting the interviews. For example, they added participants on WeChat, a widely used social media platform in China and responded to their disease-related questions through the app. This approach to establishing rapport increased the likelihood of obtaining an accurate description of their experiences. Second, prior to the study, the two interviewers systematically studied the relevant theories of qualitative research to ensure mastery of qualitative interview skills. Finally, the analysis findings were shared with the participants to gather feedback on the consistency of their actual experiences.

Patient and public involvement

The interview guide used in this study was pilot-tested with two patients to assess its clarity and appropriateness. Suggestions provided by the participants during the pilot study were incorporated into refining the guide. However, neither patients nor the public were involved in the design of this study.

Results

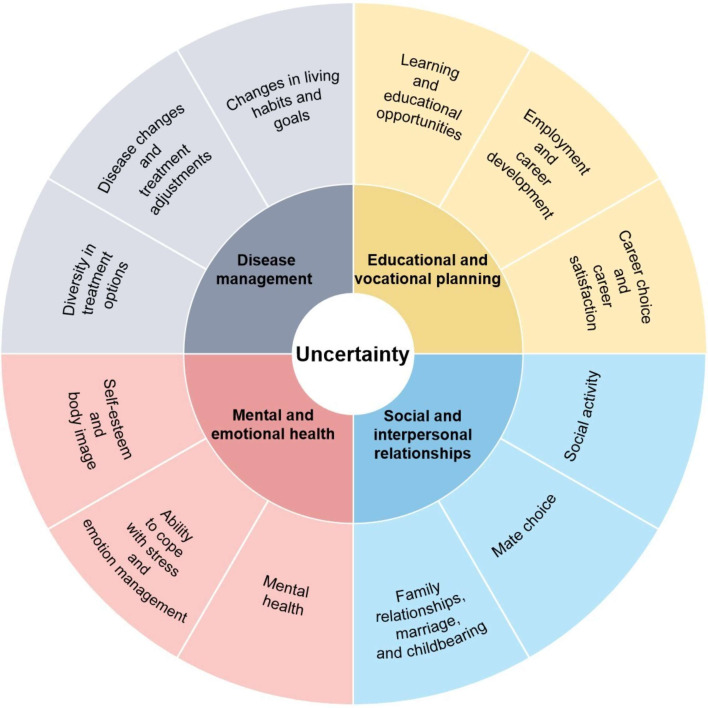

Fourteen patients with IBD (10 men and 4 women) were interviewed. The disease course varied between 6 months and 7 years. All participants received medical treatments such as biological treatments. The comprehensive demographic and clinical data are shown in table 1. The analysis resulted in the identification of four themes and 12 subthemes, which were distilled in figure 1.

Table 1. Participants’ demographics and clinical characteristics (n=14).

| Projects | Disease type | |

| CD | UC | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 23.83±3.13 | 22.75±3.54 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4 | 6 |

| Female | 2 | 2 |

| Expense category | ||

| Medical insurance | 4 | 8 |

| Self-payment | 2 | 0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 2 | 3 |

| Waiting for employment | 1 | 0 |

| Company staff | 2 | 3 |

| Freelancer | 1 | 0 |

| Resigned due to illness | 0 | 2 |

| Education level | ||

| Senior high school | 0 | 1 |

| Junior college | 2 | 3 |

| Undergraduate course | 3 | 3 |

| Graduate student | 1 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1 | 2 |

| Unmarried | 5 | 6 |

| Course of disease (months), mean±SD | 34.00±29.50 | 27.13±17.82 |

| Disease activity* | ||

| Remission | 1 | 6 |

| Mild activity | 3 | 1 |

| Moderate activity | 2 | 1 |

| Current treatment | ||

| Aminosalicylates | 3 | 3 |

| Biologic therapies | 5 | 5 |

| Nutrition therapies | 3 | 4 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine therapies | 3 | 4 |

Measured by the modified Mayo score for UC: a score of ≤2 points with no individual item score >1 indicates remission; scores of 3–5 indicate mild activity, 6–10 indicate moderate activity, and 11–12 indicate severe activity. For CD, the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index: a total score <150 indicates remission, while ≥150 indicates active disease, with 150–220 indicating mild activity, 221–450 indicating moderate activity, and >450 indicating severe activity.

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis

Figure 1. Themes and subthemes of the study. The centre circle illustrates the participants’ overall experiences. The middle circle displays the four themes, while the outer layer depicts the 12 subthemes. The themes and their corresponding subthemes are indicated by the same colour family.

Theme 1: Uncertainty in educational and vocational planning

This theme pertains to uncertainties that emerge when individuals with IBD compare themselves with others of similar age. Following their diagnosis, many participants felt that they had encountered unequal opportunities in education and career planning, resulting in a sense of bewilderment regarding their future.

Symptoms of IBD, such as emaciation, fatigue and anaemia, often manifest externally. Physical fatigue renders patients more fragile and affects their learning progress. For instance, one participant stated, ‘Due to feeling easily fatigued, I am unable to conduct experiments in the lab for extended periods, resulting in slower progress than that of others’ (P13). Mental fatigue hinders attention and affects patients’ learning efficiency. As one participant expressed, ‘I tend to be easily distracted, requiring more effort to focus and learn’ (P7). The planned treatment consumes a substantial amount of time, leading to missed educational opportunities. As one participant mentioned, ‘I frequently take sick leave to go to the hospital, and as a result, I have missed out on many classes’ (P12).

The onset of the disease can cause patients to miss opportunities to secure employment, as expressed by one participant, ‘I graduated this year, but unfortunately, I was diagnosed during the job-hunting period. I have not been able to look for a job since then and feel quite lost’ (P2). Frequent medical examinations and treatments can make it challenging for patients to maintain a stable work schedule, potentially impeding their career development. As one participant stated, ‘Bi-weekly medical treatments prevent me from travelling on official business frequently, which has impacted my career advancement’ (P8).

In some patients, symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and fatigue, can significantly affect their ability to perform physically demanding work, leading to missed job opportunities. One individual stated, ‘I used to be a programmer, and the frequent overtime work led to my recurrent illness. In the most serious case, I defecate 20 times a day, which made me extremely weak… I eventually decided to quit’ (P1). Moreover, these symptoms may affect the productivity of patients, preventing them from reaching their maximum capacity. Another patient expressed, ‘I have to take a leave of absence every eight weeks, which is a burden for me. The work I fall behind on during hospital visits… If I were not sick, I would have performed better’ (P6).

Nevertheless, some participants actively planned for their future by making personal decisions, such as re-evaluating their choice of university or considering suitable work environments. One participant said, ‘I hope to gain admission to medical school to gain a better understanding of my condition’ (P7). Another participant said, ‘During the pandemic, I had the opportunity to apply for remote work, which proved beneficial for managing my illness’ (P3).

Theme 2: Uncertainty in social and interpersonal relationships

Patients may experience changes in their symptoms or treatment that necessitate adjustments to their daily routines and work plans. These adjustments affect their social and interpersonal relationships.

According to one participant’s statement, a lack of public knowledge about IBD frequently results in insufficient social support, leading to self-isolation. The patient stated: ‘My colleagues did not understand the disease, and I gradually refrained from explaining my condition to them’ (P8). Furthermore, the unpredictable nature of the disease symptoms prevents patients from assessing their physical condition and participating in social activities. As one patient expressed it, ‘Wherever I go, I have to consider whether there is a toilet and its location. Sometimes, I have to temporarily cancel appointments with friends because of my sudden discomfort or abdominal pain. It is difficult to make plans, and sometimes I would rather stay at home’ (P5).

Owing to the disease, patients experienced abandonment by their lover and developed feelings of insecurity. They emphasised the importance of partner support. A patient shared his experience, stating, ‘Because of this disease, my girlfriend broke up with me, and I could not help but feel envious of those who remained unaffected by illness. Nonetheless, I still long for love and marriage, recognising that the support I received from my girlfriend was distinct from that of others’ (P3).

Support from family members is crucial in increasing the self-confidence of individuals with IBD. One participant emphasised the significance of this support, stating, ‘My parents and my partner understood me and provided unwavering support, which greatly encouraged me’ (P4). Regarding participants who were already parents or considering parenthood, concerns arose regarding the potential effect of the disease on pregnancy and fertility and the possibility of transmitting the disease to their children. A participant expressed her anxieties, explaining, ‘I am concerned about the potential consequences of using biological agents before and during pregnancy. Additionally, I am worried about the possibility of passing the disease on to my children’ (P4).

Theme 3: Uncertainty in mental and emotional health

The symptoms of the disease impacted the participants’ psychological state and, to some degree, restricted their daily activities. This affected their mental and emotional health to an extent that could not be ignored.

Recurrent symptoms of IBD, such as abdominal pain and blood in the stool, can trigger mood swings and sadness. For example, one participant stated, ‘My mood is directly affected by my stool condition. If there is blood in my stool, I feel worse and sometimes even cry secretly. I wonder why I have this disease’ (P12). In severe cases, some patients may develop depression and anxiety, as expressed by another participant, ‘I can’t control my thoughts. Whenever I feel changes in my gut, I become restless. People around me often say that I seem anxious, and I don’t want to feel that way’ (P6).

Psychological stress can exacerbate gut inflammation, as stated by one participant, who attributed their current recurrence of the disease to the pressure of preparing for a postgraduate entrance examination. The participant explained, ‘I think the reason for my current disease recurrence is because the pressure of the postgraduate entrance examination is immense. Even though my condition gets better, I cannot fully focus on studying because I worry about the symptoms and recurrence of the disease’ (P14). Additionally, intestinal diseases can lead to unpredictable mood changes, as described by another participant who was admitted for losing their temper over trivial things, which is not typical of their behaviour. The participant stated, ‘I often get angry with my mother over very small things. I used not to react this way before’ (the participant’s voice became increasingly frustrated while recounting this experience) (P11). Participants expressed a desire to participate in patient support groups organised by hospitals or to join online platforms to connect with other patients and receive peer support. One participant said, ‘I really enjoyed the patient support meetings organised by the department and gained valuable insights from them’ (P2).

During the unique stage of emerging adulthood, individuals become increasingly aware of their body image and its significance. This awareness often leads to a strong desire to appear ‘normal’ and hide any signs of illness or medical treatment. For instance, one participant expressed concern, stating, ‘I do not want others to know that I am sick, so I have applied for a separate dormitory with the school to perform my traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) enema every night’ (P10). Similarly, another participant found creative ways of preserving their appearance while undergoing medical treatment. The participant stated, ‘The nasal feeding pump delivers the enteral nutrition solution. I wear a mask to conceal the nasal feeding tube and carry a backpack to hold the nutrition pump discreetly. It is a practical solution for going about my daily activities’ (the participant expressed happiness while describing this approach) (P5).

Theme 4: Uncertainty in disease management

Owing to the long-term development and recurring episodes of the disease, patients with IBD may encounter challenges in choosing appropriate treatment options, including medication, surgery and lifestyle changes. They may be concerned about the effectiveness of the treatment, potential side effects, long-term risks and medical costs. Furthermore, they may experience difficulties with medication adherence and disease self-management. Consequently, they expressed their hopes and aspirations regarding TCM.

IBD, being a complex disease, has various treatment plans depending on the patient’s condition, symptoms and the doctor’s experience. Different doctors may have different treatment plans and preferences, causing confusion or uncertainty for patients. As one participant expressed, ‘I had consulted numerous doctors, and each one provided a different treatment plan. I was unsure about which one would be the most suitable for me’ (P4). Furthermore, the participants emphasised the significance of postdischarge health education, which ensured continuous medical guidance to alleviate uncertainty and confusion. One patient expressed it as follows; ‘I was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis six months ago, and while I followed the doctor’s treatment and dietary recommendations during my hospital stay, I felt completely uninformed once I returned home. TCM is known for its emphasis on health preservation, and I particularly desire to receive ongoing professional guidance even after being discharged. Through understanding the principles of TCM, I realized that recovery from illness involves not only treating the disease but also addressing factors such as diet, exercise, and emotions. Currently, I have joined the continuity of care group for discharged patients in the gastroenterology department, which makes me feel more at ease because I know there are professionals who can help me manage my condition in daily life, and I can share my experiences with other patients. I no longer feel isolated and helpless’ (P9).

Relapse of the disease leads to changes in the condition and treatment adjustments, and patients may worry about medical costs and financial burdens. One participant stated, ‘I had used infliximab for the eighth time, but unexpectedly, I experienced an allergic reaction. The doctor informed me that I had to switch medications, which worried me greatly. On the one hand, other people have been using infliximab without any allergic reactions and have been effectively managing their symptoms, except me. On the other hand, the replacement medication, ustekinumab, is not covered by medical insurance for patients with ulcerative colitis. I have to bear the entire cost myself, which adds to my financial burden’ (P3). Long-term disease progression may cause patients to become anxious about the worsening of their condition and uncertainty about what the future holds. One participant expressed confusion, stating, ‘My condition is unpredictable. Suddenly, the number of stools increased to more than 10 times a day, despite following a diet and lifestyle that should not exacerbate my symptoms. The doctor advised me to switch biologics, and it was the third time I had changed medications that year. At that moment, I did not know if I would be able to regain control over my illness, and it felt like my determination was being shattered’ (P14). As the duration of coexistence with the disease gradually increased, participants fervently pursued alternative therapeutic modalities, particularly against the background of the nationwide advocacy of TCM. As one participant conveyed, ‘I became aware of Director Shen’s profound expertise in the field of TCM, which prompted my decision to seek treatment here… After receiving navel moxibustion treatment, I always feel the warm energy flowing from my belly throughout my body, making me feel energized and alleviating all my fatigue. This has greatly enhanced my confidence and made me more positive in facing my illness’ (P8).

Symptom management requires patients to adjust their diet and exercise, which may lead to changes in their lifestyle. Additionally, individuals with this condition may need to prioritise health and disease management over other aspects of their lives. As one participant explained, ‘When I travel and try new foods, I am more concerned about whether I will experience discomfort after eating, and it is difficult to enjoy the food like others do’ (P13). Another participant said, ‘I used to like playing basketball, but now I am afraid to play because I worry it might worsen my symptoms. I cannot continue to do what I like, which made me sad for a long time. Later, I realised that changes had to be made, and during my hospitalisation, the tai chi exercise organised by the gastroenterology department strongly piqued my interest. By participating in Tai Chi, I not only found a new way to exercise but also experienced relaxation in my body and peace in my mind. The practice of Tai Chi has not only helped me alleviate anxiety but also allowed me to rediscover my love for exercise and life’ (P2).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to qualitatively explore uncertainties surrounding the future of EAI and gain insight into the experiences of individuals diagnosed with chronic, incurable diseases at a particular stage in life. This study indicated that although the disease has varying degrees of impact on patients in terms of educational and vocational planning, social and interpersonal relationships, and mental and emotional health, individuals demonstrate a positive willingness to cope with the disease in terms of disease management. They sought guidance from healthcare professionals to learn effective self-management strategies, relied on peers’ experiences and sought positive coping mechanisms. Additionally, this study also validates the potential of TCM in managing EAI from the perspective of patients.

In our study, some participants expressed the view that they had to exert more effort in addressing educational and vocational planning during critical turning points in their lives than their peers who did not have IBD, because of the challenges posed by the disease. In addition to absenteeism, the disease can significantly impact academic performance and work efficiency,23 24 even resulting in recurrent biographical disruption.25 Young adults with long-term health challenges, on average, face difficulties in participating in education and employment and have a higher likelihood of dropping out of education, employment or training by the age of 21.12 Our study further contributes to this evidence by identifying scheduled hospitalisations, examinations or consultations as the primary reasons for absenteeism or resignation. These findings suggest that healthcare providers can take steps to reduce patient absenteeism by adjusting medical plans, such as scheduling the infusion of biologics on weekends or holidays, to minimise school or work absences. Additionally, platforms such as WeChat groups can facilitate appointment services and address consultation questions from discharged patients. Meanwhile, telehealth care can help patients manage their time better and alleviate the challenges associated with frequent medical visits.

People with IBD often encounter limitations in their social interactions and activities owing to the unpredictable nature of the disease.26 In particular, adolescent patients may experience reduced interactions and contact with their peers, leading to feelings of loneliness,18 resulting in some young IBD patients letting go of friendships.27 Family support is crucial in managing chronic diseases, as evidenced by a study that found significant improvements in social functioning scores among patients with chronic diseases who received health education from their family members.28 In our study, we observed that individuals with IBD benefited from support from their family members and fellow patients, providing them with encouragement and valuable experiences. Moreover, we observed that patients of childbearing age expressed fertility concerns. These findings emphasise the importance of healthcare providers in facilitating improved communication among patients and providing health education and support for family members or partners. By doing so, they can enhance social support, alleviate feelings of loneliness and boost patients’ confidence. Additionally, it is crucial to prioritise the needs of patients of childbearing age and provide relevant health knowledge.

In our study, some participants reported experiencing mental and emotional health problems, as well as difficulties in coping. This indicates that EAI face psychological and emotional challenges, including anxiety, depression and social isolation, similar to those experienced by young individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes, vitiligo and kidney disease.29,31 Addressing mental health issues is a critical element that influences the transition of young adults living with chronic conditions.29 32 During our interviews, some participants expressed a desire to gain coping experiences from peer-support groups or online platforms. Thus, suggesting that effective psychosocial support can not only meet the emotional needs of patients but may also positively influence the physiological processes of the disease. Studies have shown that psychological interventions33 34 are significantly effective for patients with chronic diseases. Our research further emphasises the need to integrate these methods into clinical practice. Additionally, the potential of TCM to improve emotional issues in chronic disease patients should not be overlooked. For instance, a randomised, single-blind study demonstrated that herb-partitioned moxibustion could alleviate symptoms, anxiety and depression and improve the quality of life of patients with UC.35 Additionally, another randomised controlled clinical trial revealed that qigong exercise may be beneficial in reducing depression and negative thoughts while enhancing the quality of life in patients with gastrointestinal cancer.36 These findings suggest that TCM techniques could be a beneficial complement to the treatment of EAI. Therefore, we propose the following recommendations. First, clinical doctors should collaborate with mental health counsellors to master and apply psychological intervention techniques such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, mindfulness therapy and music therapy to help patients manage their emotions. Second, the number of group health education meetings organised by the digestive department must be increased to promote communication among patients, strengthen peer support and teach them skills to cope with adverse emotions. An online study demonstrated that online peer support can improve health outcomes in individuals with chronic diseases.37 Third, collaboration should be done with non-profit organisations and caring individuals to raise public awareness of IBD through media and professional platforms, thereby reducing the social dilemmas faced by EAI. Finally, the application of TCM techniques in IBD patients, such as Ba Duan Jin, Tai Chi or aromatherapy, should be explored to improve patients’ emotional well-being, as these methods have been proven effective in other chronic diseases.38,40

For the transitional preparedness of IBD patients, previous studies have focused on adolescents.41 42 However, our study emphasises the specific needs of patients aged 18–29, who are also transitioning into adulthood and need to take responsibility for understanding and managing their disease rather than relying on their parents. These patients need to gain essential skills for early independent disease management. In the Netherlands, transitional outpatient clinics have been effective in managing such patients, demonstrating lower rates of disease activity and relapse in the year following the transition, as well as positive experiences and satisfaction with the transfer process.43 These findings provide valuable insights for healthcare providers in managing the transition of these patients. Furthermore, our research discovered that EAI face considerable challenges in disease management, primarily due to the relapsing nature of the illness and individual variability. This uncertainty affects not only patients’ treatment decisions but also significantly diminishes their quality of life. Notably, postdischarge patients generally lack self-management skills and continuous medical guidance. In response to these issues, we propose the following specific and feasible measures. First, during the provision of medical services, healthcare providers should enhance patient engagement by considering personalisation.26 44 Providers should conduct comprehensive assessments and communicate with patients to implement individualised care. When formulating treatment plans, it is essential to explain the advantages and disadvantages of each option in detail, thereby increasing patients’ sense of involvement and trust. During follow-up visits, patients should be encouraged to ask questions and provide feedback, ensuring that they feel valued throughout the treatment process. Second, the services of chronic disease management platforms should be improved. This includes consistently offering one-on-one follow-up services, such as telephone consultations and online health education, to ensure that patients receive professional guidance while at home. Additionally, enhancing patients’ self-management capabilities through digital health platforms,45,47 such as mobile applications, has shown positive results. Third, we have established specialised TCM clinics for disease management. TCM specialist nurses will provide comprehensive management plans tailored to patients based on TCM syndrome differentiation, including personalised dietary recommendations aimed at alleviating symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhoea.48 Furthermore, we will utilise five-element music therapy for emotional support and teach patients about TCM qigong (such as Ba Duan Jin, five-animal boxing and Tai Chi), as well as moxibustion, cupping and aromatherapy, to improve their physical fitness and emotional well-being.38,4049 Additionally, by holding TCM health lectures, we aim to improve patients’ health literacy. In summary, by implementing personalised medical care, enhancing chronic disease management platform services and integrating TCM nursing interventions, we can help EAI effectively address the uncertainties in disease management, thereby improving their self-management capabilities and quality of life.

Limitations

This study had certain limitations. First, selection bias may have occurred, as individuals with remission or mild-to-moderate active disease and those interested in the research were more willing to complete the interviews, which may have affected the validity of the results. Second, the conservative nature of Chinese culture may have affected the young participants, potentially leading them not to discuss the impact of the disease on their intimate relationships and sexual abilities. Finally, although a sufficient number of subjects were recruited to achieve data adequacy, this was an exploratory study conducted at a tertiary hospital in eastern China, making the generalisability of the results to other settings limited. These limitations must be accounted for when considering the broad relevance of these findings.

Practical implications

To address the uncertainty of illness effectively, healthcare providers must assist patients in promptly resolving their doubts. This support should consider the patient’s age and the varying impact of the disease on their life and provide them with holistic and continuous support throughout their journey. Therefore, ensuring consistent medical guidance during home-care is critical. Healthcare professionals can enhance their interventions and support systems by gaining a comprehensive understanding of patients’ experiences and coping mechanisms, tailoring their approaches to meet the specific needs of Chinese culture and improving the management of individuals with IBD using TCM.

Conclusion

This study presents insights into the challenges encountered by EAI, along with their potential influence on their experiences. Furthermore, it highlights TCM as a promising approach for tackling these uncertainties. Additionally, it suggests the need for healthcare providers to devise suitable support and intervention strategies to guide and establish stable the future management of the condition.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the 14 participants who generously shared their experiences.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was funded by the Key Specialised Project of the Nursing Department of Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine (2021-2023).

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-089213).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants. The study was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine Ethics Committee (approval no. 2023NL-004-02). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Yu Zhou, Email: 15850531734@163.com.

Ranran Qiao, Email: 20211015@njucm.edu.cn.

Tengteng Ding, Email: 20221066@njucm.edu.cn.

Hui Li, Email: 787649216@qq.com.

Ping Zhang, Email: zpjsszyyxhk@163.com.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

References

- 1.Johnston RD, Logan RFA. What is the peak age for onset of IBD? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:S4–5. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorrentino D. The Coming of Age of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Asia. Inflamm Intest Dis . 2017;2:93–4. doi: 10.1159/000480731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng SC, Kaplan GG, Tang W, et al. Population Density and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Population-Based Study in 13 Countries or Regions in Asia-Pacific. Am J Gastroenterol . 2019;114:107–15. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Q, Zhu C, Feng S, et al. Economic Burden and Health Care Access for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in China: Web-Based Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e20629. doi: 10.2196/20629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2003;100:63–75. doi: 10.1002/cd.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood D, Crapnell T, Lau L. In: Handbook of life course health development. Stuber TH, Smith KA, editors. New York: Springer; 2018. Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course; pp. 123–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok E, Henderson M, Dasgupta K, et al. Group education for adolescents with type 1 diabetes during transition from paediatric to adult care: study protocol for a multisite, randomised controlled, superiority trial (GET-IT-T1D) BMJ Open. 2019;9:e033806. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John AS, Jackson JL, Moons P, et al. Advances in Managing Transition to Adulthood for Adolescents With Congenital Heart Disease: A Practical Approach to Transition Program Design: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025278. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.025278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simeone S, Mercuri C, Cosco C, et al. Enacted Stigma in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Italian Phenomenological Study. Healthcare (Basel) -> Healthc (Basel) 2023;11:474. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11040474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo L, Rohde J, Farraye FA. Stigma and Disclosure in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1010–6. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasalingam A, Brekke I, Dahl E, et al. Impact of growing up with somatic long-term health challenges on school completion, NEET status and disability pension: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:514. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10538-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng L, Jetha A, Cordeaux E, et al. Workplace challenges, supports, and accommodations for people with inflammatory bowel disease: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:7587–99. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1979662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trivedi I, Keefer L. The Emerging Adult with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Challenges and Recommendations for the Adult Gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807. doi: 10.1155/2015/260807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menon T, Afzali A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Practical Path to Transitioning From Pediatric to Adult Care. Am J Gastroenterol . 2019;114:1432–40. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Touma N, Zanni L, Blanc P, et al. Digesting Crohn’s Disease: The Journey of Young Adults since Diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/jcm12227128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fourie S, Jackson D, Aveyard H. Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A review of qualitative research studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;87:149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Wang D, Zhou Y. The Illness Experiences of Chinese Adolescent Patients Living with Crohn Disease: A Descriptive Qualitative Study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2023;46:95–106. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Zhou Y. The symptom experience of newly diagnosed Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease: A longitudinal qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79:3824–36. doi: 10.1111/jan.15721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical Association Chinese consensus on diagnosis and treatment in inflammatory bowel disease (2018, Beijing) J of Digest Dis. 2021;22:298–317. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it n.d.

- 22.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes C, Ashton JJ, Borca F, et al. Children and young people with inflammatory bowel disease attend less school than their healthy peers. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105:671–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langbrandtner J, Steimann G, Reichel C, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease - Challenges in the Workplace and Support for Coping with Disease. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2022;61:97–106. doi: 10.1055/a-1581-6497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saunders B. “It seems like you’re going around in circles”: recurrent biographical disruption constructed through the past, present and anticipated future in the narratives of young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39:726–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoefs E, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, et al. What are the Unmet Needs and Most Relevant Treatment Outcomes According to Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease? A Qualitative Patient Preference Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:379–88. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouncefield-Swales A, Carter B, Bray L, et al. Sustaining, Forming, and Letting Go of Friendships for Young People with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Qualitative Interview-Based Study. Int J Chronic Dis. 2020;2020:7254972. doi: 10.1155/2020/7254972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saidi SS, Abdul Manaf R. Effectiveness of family support health education intervention to improve health-related quality of life among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Melaka, Malaysia. BMC Pulm Med . 2023;23:139. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02440-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edmondson EK, Garcia SM, Gregory EF, et al. Emerging Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: Understanding Illness Experience and Transition to Adult Care. J Adolesc Health. 2024;75:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2024.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eleftheriadou V, Delattre C, Chetty-Mhlanga S, et al. Burden of disease and treatment patterns in patients with vitiligo: findings from a national longitudinal retrospective study in the UK. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:216–24. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljae133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mai K, Dawson AE, Gu L, et al. Common mental health conditions and considerations in pediatric chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2024;39:2887–97. doi: 10.1007/s00467-024-06314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho R, Wickert NM, Klassen AF, et al. Identifying Needs in Young Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Qualitative Study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2018;41:19–28. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng LL, Zhang Y, Li CL. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on emotional intervention among type 2 diabetes patients with mild to moderate anxiety and depression in community. Chin J Health Educ. 2024;40:647–51. doi: 10.16168/j.cnki.issn.1002-9982.2024.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu JQ, Zhao JG, Ma LL, et al. Research progress on application of problem-solving therapy in patients with chronic disease. Chin Nurs Res. 2024;38:2350–4. doi: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2024.13.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin QI, Im H, Kunshan LI, et al. Influence of herb-partitioned moxibustion at Qihai (CV6) and bilateral Tianshu (ST25) and Shangjuxu (ST37) acupoints on toll-like receptors 4 signaling pathways in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Trad Chin Med. 2021;41 doi: 10.19852/j.cnki.jtcm.20210310.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang L-H, Duan P-B, Hou Q-M, et al. Qigong Exercise for Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy and at High Risk for Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27:750–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su J, Dugas M, Guo X, et al. Building social identity-based groups to enhance online peer support for patients with chronic disease: a pilot study using mixed-methods evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2022;12:702–12. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibac008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo X, Zhao M, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of baduanjin exercise on blood glucose, depression and anxiety among patients with type II diabetes and emotional disorders: A meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2023;50:S1744-3881(22)00170-0. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng Y, Liu J, Liu P, et al. Traditional Chinese exercises on depression: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Abingdon) 2024;103:e37319. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akbaş Uysal D, Şenuzun Aykar F, Uyar M. The effects of aromatherapy and music on pain, anxiety, and stress levels in palliative care patients. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32:632. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feingold JH, Kaye-Kauderer H, Mendiolaza M, et al. Empowered transitions: Understanding the experience of transitioning from pediatric to adult care among adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and their parents using photovoice. J Psychosom Res. 2021;143:S0022-3999(21)00045-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou M, Xu Y, Zhou Y. Factors influencing the healthcare transition in Chinese adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a multi-perspective qualitative study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:445. doi: 10.1186/s12876-023-03080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sattoe JNT, Peeters MAC, Haitsma J, et al. Value of an outpatient transition clinic for young people with inflammatory bowel disease: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e033535. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louis E, Ramos-Goñi JM, Cuervo J, et al. A Qualitative Research for Defining Meaningful Attributes for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease from the Patient Perspective. Patient. 2020;13:317–25. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00407-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blunck D, Kastner L, Nissen M, et al. The Effectiveness of Patient Training in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Knowledge via Instagram: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e36767. doi: 10.2196/36767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tu W, Yan S, Yin T, et al. Mobile-based program improves healthy eating of ulcerative colitis patients: A pilot study. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231205741. doi: 10.1177/20552076231205741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huisman D, Burrows T, Sweeney L, et al. “Symptom-free” when inflammatory bowel disease is in remission: Expectations raised by online resources. Pat Educ Couns. 2024;119:S0738-3991(23)00415-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.108034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen C, Dai XJ, Xu ZQ, et al. Effect of traditional Chinese medicine transitional care among patients with ulcerative colitis. Chin Nurs Manage. 2016;16:164–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2016.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Yin L, Peng Y, et al. Effect of five-elements music therapy combined with Baduanjin qigong on patients with mild COVID-19. Hong Kong J Occup Ther . 2023;36:31–8. doi: 10.1177/15691861231167536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]