Abstract

Background

Despite the known benefits of modern contraceptives in preventing unwanted pregnancies and reducing unsafe abortions, their use remains low among women of reproductive age in several sub-Saharan African countries, including Sierra Leone. This study investigated the inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone based on data from 2008 to 2019.

Methods

We used data from the Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey data rounds (2008, 2013, and 2019). The World Health Organization's Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (WHO's HEAT) software was used to calculate both simple measures; Difference (D) and Ratio (R) and complex measures of inequality: Population Attributable Risk (PAR) and Population Attributable Fraction (PAF). The inequality assessment was done for five stratifiers: age, economic status, level of education, place of residence, and sub-national province.

Results

The study found that the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone increased from 6.7% in 2008 to 20.9% in 2019. There was an increase in age-related inequality from a Difference of 5.9 percentage points in 2008 to 7.0 percentage points in 2019. PAF decreased from 5.7% in 2008 to 1.6% in 2019, indicating that the national average of modern contraceptive use would have increased by 5.7% in 2008 and 1.6% in 2019 in the absence of age-related inequalities. For economic status, the Difference decreased from 14.9 percentage points in 2008 to 9.9 percentage points in 2019. PAF decreased from 166.3% in 2008 to 23.3% in 2019, indicating that the national average of modern contraceptive use would have increased by 166.3% in 2008 and 23.3% in 2019 in the absence of economic-related inequalities. For education, the Difference decreased from 15.1 percentage points in 2008 to 12.4 percentage points in 2019. The PAF shows that the national average of modern contraceptive use would have reduced from 189.8% in 2008 to 39.5% in 2019, in the absence of education-related inequality. With respect to place of residence, the Difference decreased from 10.4 percentage points in 2008 to 7.6 percentage points in 2019, and PAF decreased from 111.2% in 2008 to 23.0% in 2019. The decline in PAF indicates that the national average of modern contraceptive use would have increased by 111.2% in 2008 and 23.0% in 2019 without residence-related inequality. Provincial-related inequality decreased from a Difference of 15.5% in 2008 to 8.5% in 2019. The PAF results showed a decrease in inequality from 176.3% in 2008 to 16.7% in 2019, indicating that province would contribute 176.3% and 16.7% in 2008 and 2019 respectively to the national average of modern contraceptive use.

Conclusion

The use of modern contraceptives among women of reproductive age in Sierra Leone increased between 2008 and 2019 reflecting positive progress in reproductive health initiatives and access to family planning resources. The reductions in inequalities related to economic status, education, residence, and province indicate that efforts to promote equity in contraceptive access are yielding results, although age-related inequalities persist. To build on these advancements, it is recommended that policymakers continue to strengthen educational campaigns and healthcare services, particularly targeting younger women. Additionally, enhancing access to contraceptive methods through community-based programs and addressing socio-economic barriers will be crucial in further reducing inequalities and improving overall reproductive health outcomes in Sierra Leone.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12978-024-01900-3.

Keywords: Contraception, Modern, Health, Inequality, Sierra Leone, Demographic health survey

Introduction

Modern contraception refers to safe and effective methods that enable women to control unwanted pregnancies [1]. This includes a wide range of options like pills, injectables, implants, condoms, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). These methods allow women to space pregnancies, which reduces maternal mortality and morbidity risks [2]. They also help to improve child health outcomes by ensuring adequate spacing between births and allowing mothers time to recover their physical resources [2]. The potential non-health benefits include increased educational opportunities and empowerment for women, sustainable population growth, and economic development in countries [3, 4].

Out of the 1.9 billion women aged 15–49 worldwide in 2021, 1.1 billion require family planning. Among them, 874 million are now using modern contraceptive methods, while 164 million need contraception, which is not being satisfied [1]. The global satisfaction rate of the demand for family planning by modern methods, as measured by Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) indicator 3.7.1, has remained stagnant at approximately 77% from 2015 to 2022. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, this rate has increased from 52 to 58%[2]. The global contraceptive prevalence rate for any method in 2022 was 65%, while the prevalence rate for modern methods among married or women in a union was 58.7% [5]. The 2019 Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey reported that the contraceptive prevalence rate is 24% for all women, 21% for currently married women, and 53% for sexually active unmarried women [6]. The prevailing modern contraceptive methods used by currently married women are injectables (9%), implants (7%), and the pill (4%) [6]. These numbers are lower than what is reported globally and in sub-Saharan Africa, emphasising the presence of unmet need for contraception.

In this regard, the Sierra Leone government and partner organisations are working to improve access to modern contraception. Some measures include establishing nationwide family planning services in health facilities [7]. Mass media and community outreach programs address misconceptions and increase awareness about family planning benefits [8]. Initiatives aim to reduce the cost of contraceptives, making them more affordable for low-income women. However, challenges persist, and women in rural areas often face geographical barriers and lack of service availability compared to urban settings [7]. Gender norms and religious beliefs can influence women's autonomy over reproductive choices [9]. Uneven distribution and insufficiently trained healthcare providers can disrupt service delivery [7, 9]. In addition, the use of contraceptives varies across socioeconomic status, age and region of residence. Among currently married women, 29% of those with a secondary education utilise at least one modern method of contraception, while only 17% of those without any education do the same. Urban areas have a higher prevalence of modern contraceptive methods among currently married women, with 26% using them, compared to rural areas where only 18% use them. Contraceptive usage varies throughout districts, ranging from 7% in Falaba to 32% in Kailahun [6].

The use of contraceptives among women in Sierra Leone is influenced by a complex interplay of socio-economic and demographic factors that contribute to inequalities [10]. Key variables such as economic status, educational attainment, place of residence, and regional disparities play a pivotal role in shaping access to and utilization of contraceptive methods [11, 12]. Women from higher economic backgrounds are more likely to access contraceptive services, as financial constraints often limit options for those in lower income brackets [13]. Additionally, education emerges as a critical determinant; women with higher levels of education tend to have greater awareness and understanding of reproductive health options, leading to increased contraceptive use [14]. Geographic location also impacts access, with urban women generally enjoying better healthcare infrastructure and availability of services compared to their rural counterparts [15]. Furthermore, regional variations reflect local cultural norms and practices that can either facilitate or hinder the adoption of modern contraceptives [11]. By examining these factors, our study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the inequalities in contraceptive use, thereby informing public policy and contributing to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 3.7, which advocates for universal access to sexual and reproductive health services.

Prior research in Sierra Leone has investigated various aspects of contraception, including the impact of family planning messages and the utilisation of modern contraceptives [16], patterns and factors influencing modern contraceptive use among adolescents [17], the prevalence of contraceptive use among married or cohabiting women in Sierra Leone [18], the relationship between household decision making and contraceptive use [19], the underlying causes of unmet need for contraception [20], the intention to use contraceptives among married and cohabiting women [21], and the effectiveness of contraceptive counselling [22]. This leaves a gap in the literature on the trends and inequalities in modern contraceptive use. Therefore, this study aims to examine the trends and inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone. By identifying these inequalities, policymakers can design targeted interventions to address the specific needs of disadvantaged groups. The study can provide a baseline for measuring the effectiveness of existing programs and inform future strategies. By examining inequalities in modern contraceptive use from 2008 to 2019, this study can offer valuable insights for improving women's reproductive health and well-being in Sierra Leone. This will contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3.7, which focuses on ensuring universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including family planning, information & education, & the integration of reproductive health into national strategies.

Methods

Context of the study

Sierra Leone, a country in West Africa, has faced substantial challenges in reproductive health, particularly in the realm of modern contraceptive use, between 2008 and 2019 [10]. Following a decade-long civil war that ended in 2002, the country has been striving to rebuild its healthcare system and improve health outcomes for women [23]. During this period, the government, alongside various international organizations, implemented several policies and programs aimed at enhancing access to reproductive health services. Notably, the National Reproductive Health Policy, revised in 2015, emphasized the importance of family planning as a critical component of maternal and child health [24]. This policy aimed to increase the availability of contraceptive options and reduce unmet needs for family planning.

Additionally, the introduction of the Free Healthcare Initiative in 2010 aimed to eliminate financial barriers to healthcare for pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children under five, indirectly impacting access to reproductive health services, including modern contraception [25]. Various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) also played a crucial role in promoting awareness and providing contraceptive services, particularly in rural areas where access has historically been limited [7].

Despite these efforts, challenges remain, including cultural stigma surrounding contraceptive use, limited education regarding reproductive health, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure, particularly in remote regions [24]. Understanding these contextual factors is essential for interpreting the trends and inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone during the study period. By situating our research within this framework, we aim to elucidate how these policies and socio-cultural dynamics have influenced contraceptive access and usage, ultimately contributing to the broader discourse on reproductive health in the country.

Study design and source

We used data from the 2008, 2013, and 2019 Sierra Leone Demographic Health Surveys (SLDHS). The SLDHS is a nationwide survey that aims to identify consistent trends and changes in demographic indicators, health indicators, and social issues among individuals of all genders and age groups. The SLDHS had a cross-sectional design in which participants were chosen using a stratified multi-stage cluster sampling method. A detailed description of the sampling methodology can be found in the SLDHS report [6]. This study comprised of women aged 15–49 in the corresponding SLDHS cycles. The 2008, 2013, and 2019 SLDHS data were available for direct use using the WHO HEAT online platform [26]. This study was done following the guidelines specified in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [27].

Variables

The dependent variable for the study was modern contraceptive use. Women who used modern contraceptives were classed as “using”, while those who did not use modern contraceptives were classified as “not using”. The assessment of inequality in modern contraceptives utilised five stratifiers: age (15–19 and 20–49), economic status measured by wealth quintile (quintile 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), level of education (no education, primary education, secondary/higher education), place of residence (rural, urban), and sub-national province (Eastern, Northern, Northwestern, Southern, Western).

Data analysis

The online version of the WHO HEAT software was used to analyze the trends and inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone [26]. HEAT is designed primarily for descriptive analysis, allowing researchers to assess health equity by comparing health indicators across different population subgroups [28, 29]. This tool facilitates the identification of disparities related to socio-economic factors, education, and geographic location. The factors encompassed are age, economic status, level of education, place of residence, and sub-national province. Estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess modern contraception use among women, considering the specified stratifiers. Four metrics were utilised to calculate inequality: Difference (D), Population Attributable risk (PAR), Population Attributable Fraction (PAF), and Ratio (R). Two simple measurements, D and R, are not affected by weight, while two more complex measures, PAR and PAF, are influenced by weight. R and PAF are relative metrics. However, D and PAR are absolute measures. Considering summary measures is grounded in the WHO's recognition that absolute and relative summary measurements are essential for deriving policy-driven findings. In contrast to simple measurements, complex measures consider the magnitude of categories within a specific population subset. The literature has comprehensively provided information about the World Health Organization's summary measures and calculations [28, 29].

Results

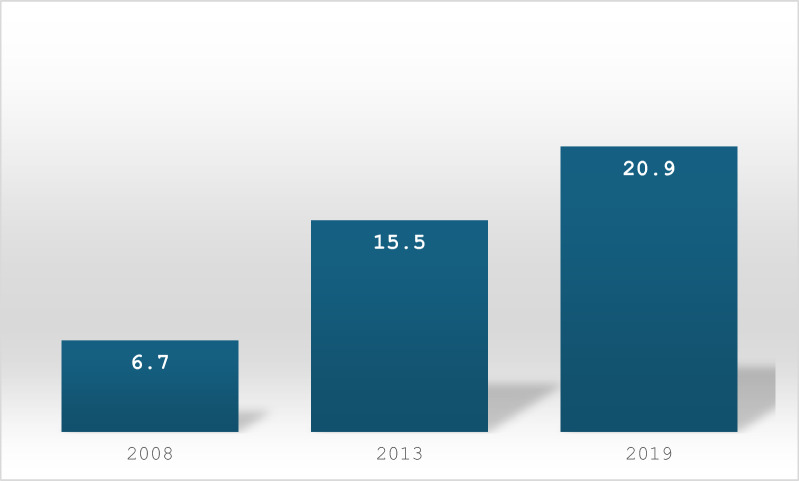

Figure 1 shows the modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone. Modern contraceptive use increased from 6.7% in 2008 to 20.9% in 2019.

Fig. 1.

Modern contraceptive use prevalence among women in Sierra Leone.

Source: Authors analysis, 2024

Table 1 shows trends in modern contraceptive use in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019. Use increased across all age groups, but the most significant increase was among older women (20–49). Consistently, the wealthier quintiles had a higher prevalence of modern contraceptive use compared to poorer ones. The gap narrowed slightly over time. Like economic status, women with higher education had a significantly higher prevalence of modern contraceptive use compared to those with no education. Over time, the gap decreased marginally. Urban women consistently had a higher prevalence of modern contraceptive use compared to rural women. The gap became smaller over time. Modern contraceptive use prevalence increased in all provinces, but the Western area consistently had the highest prevalence, followed by the Southern and Eastern. The Northern and Northwestern provinces had the lowest prevalence. It’s important to note that between 2008 and 2013 Sierra Leone had four regions and could have contributed to the low prevalence in Northwestern province which was only created recently.

Table 1.

Trends in the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone by different inequality dimensions, 2008–2019

| Dimension | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | LB | UB | N | % | LB | UB | N | % | LB | UB | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 15–19 | 358 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 729 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 10.3 | 477 | 14.2 | 11.0 | 18.2 |

| 20–49 | 5166 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 1017 | 16.1 | 14.9 | 17.4 | 9237 | 21.2 | 20.0 | 22.5 |

| Economic status | ||||||||||||

| Quintile 1 (poorest) | 1178 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 2341 | 11.4 | 9.6 | 13.4 | 2079 | 15.8 | 14.1 | 17.7 |

| Quintile 2 | 1143 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 2323 | 11.4 | 9.8 | 13.3 | 2134 | 17.8 | 15.8 | 20.1 |

| Quintile 3 | 1185 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 2306 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 14.2 | 1979 | 20.8 | 18.4 | 23.3 |

| Quintile 4 | 1050 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 10.9 | 2086 | 19.1 | 16.9 | 21.5 | 1770 | 25.9 | 23.7 | 28.2 |

| Quintile 5 (richest) | 966 | 17.9 | 14.6 | 21.8 | 1845 | 26.3 | 23.4 | 29.4 | 1750 | 25.8 | 22.7 | 29.1 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education | 4280 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 5.2 | 7869 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 5956 | 16.7 | 15.4 | 18.1 |

| Primary education | 601 | 9.4 | 7.0 | 12.5 | 1425 | 18.9 | 16.4 | 21.6 | 1297 | 24.5 | 21.6 | 27.7 |

| Secondary or higher education | 643 | 19.5 | 16.2 | 23.3 | 1607 | 24.6 | 21.9 | 27.5 | 2460 | 29.2 | 27.0 | 31.5 |

| Place of residence | ||||||||||||

| Rural | 3964 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 7980 | 12.2 | 10.9 | 13.6 | 6136 | 18.1 | 16.6 | 19.6 |

| Urban | 1560 | 14.2 | 11.7 | 17.1 | 2922 | 24.7 | 22.2 | 27.3 | 3578 | 25.7 | 23.7 | 27.8 |

| Province | ||||||||||||

| Eastern | 1027 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 7.1 | 2557 | 16.5 | 14.3 | 18.9 | 2007 | 23.4 | 20.8 | 26.2 |

| Northern | 2434 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 4398 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 13.3 | 2172 | 17.5 | 15.1 | 20.3 |

| Northwestern | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1760 | 15.9 | 13.5 | 18.5 |

| Southern | 1205 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 9.0 | 2434 | 16.2 | 14.1 | 18.6 | 1894 | 23.2 | 20.7 | 26.0 |

| Western | 857 | 18.6 | 15.0 | 22.8 | 1512 | 24.9 | 20.9 | 29.4 | 1880 | 24.4 | 21.4 | 27.6 |

LB: lower bound; UB: upper bound; N: sample size; NA: Not available

Table 2 shows the inequality in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone between 2008 and 2019. The inequality in age increased over time from a Difference of 5.9 percentage points in 2008 to 7.0 percentage points in 2019, indicating a slight increase in age-related disparities. The PAF shows that if there were no age-related inequality, the national average for modern contraceptives would have been 5.7% and 1.6% higher in 2008, and 2019 respectively.

Table 2.

Inequality measures of estimates of factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone, 2008–2019

| Dimension | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | LB | UB | Est | LB | UB | Est | LB | UB | |

| Age | |||||||||

| D | 5.9 | 4.0 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 5.7 | 10.9 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 10.8 |

| PAF | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| PAR | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| R | 5.9 | 1.6 | 22.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| Economic status | |||||||||

| D | 14.9 | 11.2 | 18.7 | 14.8 | 11.3 | 18.4 | 9.9 | 6.3 | 13.6 |

| PAF | 166.3 | 166.0 | 166.6 | 68.8 | 68.7 | 69.0 | 23.3 | 23.3 | 23.4 |

| PAR | 11.2 | 9.3 | 13.0 | 10.7 | 8.9 | 12.4 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 6.7 |

| R | 6.0 | 3.8 | 9.4 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Education | |||||||||

| D | 15.1 | 11.5 | 18.7 | 11.5 | 8.4 | 14.5 | 12.4 | 9.8 | 15.1 |

| PAF | 189.8 | 189.4 | 190.1 | 58.1 | 57.9 | 58.2 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.6 |

| PAR | 12.8 | 10.2 | 15.3 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 10.9 | 8.2 | 6.7 | 9.7 |

| R | 4.4 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| D | 10.4 | 7.6 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 9.6 | 15.3 | 7.6 | 5.0 | 10.1 |

| PAF | 111.2 | 111.0 | 111.4 | 58.6 | 58.5 | 58.6 | 23.0 | 22.9 | 23.0 |

| PAR | 7.5 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 10.3 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 5.9 |

| R | 3.7 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 2.01 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Province | |||||||||

| D | 15.5 | 11.5 | 19.5 | 13.5 | 8.8 | 18.1 | 8.5 | 4.5 | 12.5 |

| PAF | 176.3 | 176.0 | 176.6 | 60.0 | 59.9 | 60.1 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.8 |

| PAR | 11.8 | 9.8 | 13.9 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 11.3 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 5.2 |

| R | 6.0 | 4.2 | 8.4 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

Est; estimate; LB: lower bound; UB: upper bound

The economic status disparity decreased from a Difference of 14.9 percentage points in 2008 to 9.9 percentage points in 2019. The PAF reveal that the national average of modern contraceptive use could have been 166.3% higher in 2008, and 23.3% higher in 2019 without economic status inequality.

Inequality for education decreased slightly from a Difference of 15.1 percentage points in 2008 to 12.4 percentage points in 2019. The PAF indicates inequalities in education contributes 189.8% in 2008 and 39.5% in 2019 to the national average of modern contraceptive use.

For place of residence, the Difference increased from 10.4 percentage points in 2008 to 12.4 percentage points in 2013 but decreased to 7.6% in 2019. The PAF reveals that the national average of modern contraceptive use could have been 111.2% higher in 2008, and 23.0% higher in 2019, without inequalities related to place of residence.

Provincial disparity decreased from a Difference of 15.5 percentage points in 2008 to 8.5 percentage points in 2019. The PAF indicates that the national average of modern contraceptive use would have increased by 176.3% in 2008 and 16.7% in 2019, without provincial inequality.

Discussion

The study examined the inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone between 2008 and 2019. The study found that the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone has increased significantly from 6.7% in 2008 to 20.9% in 2019. Overall, the results show that Sierra Leone has made progress in reducing inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women across various dimensions from 2008 to 2019. The decreasing trends in disparity, PAF, PAR, and ratios indicate that the gaps in contraceptive use due to economic status, education, place of residence, and region are narrowing. This implies that interventions and policies implemented during this period may have effectively addressed these inequalities.

Our study found that the prevalence of modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone has increased significantly from 6.7% in 2008 to 20.9% in 2019. Our finding prevalence is similar to the 18.1% reported among married or in-union women in Sierra Leone[12]. However, this rate remains notably lower than the African regional average of approximately 50% [2]. Sierra Leone has faced significant socio-economic challenges, including the aftermath of a devastating civil war, which has hindered the development of healthcare infrastructure and access to essential services [23]. Limited availability of family planning resources, particularly in rural areas, can restrict women's access to modern contraceptives [7]. Additionally, cultural beliefs and stigma surrounding contraceptive use may further impede acceptance and utilization, particularly in more conservative communities [24]. Also, the effectiveness of family planning programs and policies in Sierra Leone may not have reached the same level of implementation and impact as seen in other African countries, where comprehensive strategies have been employed to enhance contraceptive access and education [8].

The disparity in modern contraceptive use by age in Sierra Leone increased from 2008 to 2019, specific initiatives, such as the National Family Planning Program, have aimed to improve access to contraceptive services for women, yet there remains a gap in targeted interventions for younger populations [7]. Factors contributing to persistent inequalities include cultural norms that prioritize reproductive roles for older women, limited access to youth-friendly services, and a lack of comprehensive education about contraceptive options for younger women [30]. Evidence from neighboring countries like Ghana and Nigeria shows that inclusive programs addressing the unique needs of all age groups can enhance contraceptive uptake [31]. For instance, Ghana’s community-based outreach strategies have successfully engaged both younger and older women, highlighting the importance of tailored interventions [32]. Further research is essential to explore the specific barriers faced by younger women in Sierra Leone, ensuring that family planning programs are effectively inclusive and responsive to the needs of all age groups.

The decrease in disparity in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone, particularly concerning education and economic status, indicates progress in making contraception more accessible across various backgrounds. This finding is consistent with the previous studies [33–35]. Specific initiatives, such as the Free Health Care Initiative and the National Family Planning Program, have aimed to provide subsidized or free contraceptives, particularly benefiting low-income women [24, 25]. Additionally, campaigns like Family Planning for All have focused on educating women in low-income communities about the benefits and availability of modern contraception through workshops and community leader engagement [9]. The establishment of more clinics and pharmacies in underserved areas has also improved access [36]. However, persistent inequalities remain, largely due to cultural norms that prioritize traditional reproductive roles, limited health literacy, and the socio-economic barriers that continue to affect low-income women disproportionately [37]. Evidence from low-and middle-income countries comprehensive family planning approach and targeted outreach programs, demonstrates the importance of inclusive strategies that address the unique needs of both low-income and educated women [38]. To further enhance contraceptive uptake, it is crucial to continue addressing cultural barriers and promote gender equality, ensuring that all women can make informed choices about their reproductive health in Sierra Leone.

The rise and subsequent fall of place of residence inequality in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019 reflects significant changes in access to family planning services. Between 2008 and 2013, limited availability of these services in rural areas likely perpetuated a consistent disparity, as many rural women faced barriers such as distance to health facilities, lack of transportation, and insufficient healthcare infrastructure [39]. However, the period from 2013 to 2019 may have seen a concerted effort to address these issues, with initiatives such as the expansion of mobile clinics, training programs for rural health workers, and community awareness campaigns that effectively increased access to contraceptives for rural populations [24]. Despite these advancements, persistent inequalities can still be attributed to factors such as cultural norms that discourage contraceptive use, limited education about reproductive health, and economic constraints that disproportionately affect rural women [40]. For instance, similar trends in neighboring countries like Liberia and Ghana highlight the importance of targeted interventions in rural areas; Liberia's community-based distribution programs have successfully improved contraceptive access [41], while Ghana's integration of family planning into primary healthcare has reduced disparities [31]. These examples underscore the need for continued focus on addressing the unique challenges faced by rural women in Sierra Leone, ensuring that family planning services are not only accessible but also culturally accepted and economically feasible.

The decrease in provincial disparity in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019 indicates progress toward more equitable access to family planning services. Engaging local communities has been crucial in promoting awareness and education about contraceptive use; initiatives that involve community leaders, women’s groups, and religious figures have been effective in addressing cultural barriers and fostering acceptance of family planning [24]. However, persistent inequalities can still be traced to underlying factors such as socio-economic disparities, varying levels of health literacy, and infrastructural challenges [7]. For instance, while investments in improving roads and transportation networks have facilitated access to clinics in some areas, remote regions may still lack adequate healthcare facilities and trained personnel, limiting service availability [42]. Evidence from similar countries, such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Malawi have successfully reduced regional disparities through community health worker programs and targeted outreach, underscores the importance of tailored interventions that consider local contexts [43]. To sustain the momentum in reducing provincial disparities in Sierra Leone, it is essential to continue addressing these systemic barriers while ensuring that all communities, particularly those in remote areas, benefit from improved access to comprehensive family planning services.

Policy and practice implications

Our study on modern contraceptive use in Sierra Leone (2008–2019) offers valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners working on family planning programs. The significant rise in modern contraceptive use suggests that existing policies and programs have been effective in raising awareness and improving access. This is a positive foundation for further progress. The decline in inequalities based on residence, and province indicates a broader reach of family planning services. This suggests a successful approach to reaching diverse populations. Although reduced, economic status remains a key factor in contraceptive access. Policies promoting women's economic empowerment and poverty reduction could have a significant impact. This could involve microfinance initiatives, vocational training, or childcare support. While educational gaps are narrowing, continued efforts to increase girls' education can have a long-term impact. This could involve scholarships, addressing gender biases, or improving rural education access. The study highlights the importance of acknowledging remaining provincial disparities. Policies and programs should be adapted to address the specific needs of lagging provinces. This might involve campaigns or clinics, culturally sensitive information campaigns, or training local healthcare providers. Continued monitoring of contraceptive use trends across different demographics is crucial. This allows policymakers to identify emerging inequalities and adapt programs accordingly. Evaluating the effectiveness of existing interventions is essential. Understanding what works best can help optimise resource allocation and program design. By implementing these policy and practice changes, Sierra Leone can ensure equitable access to modern contraception for all women, regardless of age, economic status, education level, residence, or province.

Strengths and limitations

The SLDHS is a nationally representative survey that provides data from a large and diverse sample of women in Sierra Leone. This ensures the study findings can be confidently generalised to the broader population. The SLDHS collects data on a wide range of variables related to contraception and reproductive health, including demographics, socioeconomic status, and contraceptive use. This allows for a comprehensive analysis of how different factors influence contraceptive use inequalities. WHO Heat software is a powerful tool for visualising complex data sets. It can be used to create clear and informative charts that effectively communicate the trends and inequalities in modern contraceptive use across different groups of women in Sierra Leone. The limitation of using SLDHS and WHO Heat software is that SLDHS provides data at a single point. While it can show trends over time (2008–2019), it cannot definitively establish cause-and-effect relationships between factors and contraceptive use. Like any survey, the SLDHS is susceptible to reporting bias. Women might be hesitant to answer truthfully about sensitive topics like contraception. The SLDHS and WHO Heat software primarily focus on quantitative data. They don't capture the lived experiences and reasons behind contraceptive use inequalities.

Conclusion

The increase in modern contraceptive use among women in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019 reflects positive progress in reproductive health initiatives and access to family planning resources. The reductions in disparities related to economic status, education, residence, and region indicate that efforts to promote equity in contraceptive access are yielding results, although age-related inequalities persist. To build on these advancements, it is recommended that policymakers continue to strengthen educational campaigns and healthcare services, particularly targeting younger women and provinces with lower use. Additionally, enhancing access to contraceptive methods through community-based programs and addressing socio-economic barriers will be crucial in further reducing inequalities and improving overall reproductive health outcomes in Sierra Leone.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to MEASURE DHS and the World Health Organization for making the dataset and the HEAT software accessible. We wish to thank Abdul-Aziz Seidu for his contributions during the initial draft of the manuscript and his critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- D

Difference

- HEAT

Health Equity Assessment Toolkit

- DHS

Demographic Health Survey

- PAF

Population Attributable Fraction

- PAR

Population Attributable Risk

- R

Ratio

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

AO and BOA contributed to the study design and conceptualisation. AO and BOA performed the analysis. AO, CB, and BOA developed the initial draft. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. All authors read and amended drafts of the paper and approved the final version. AO had the final responsibility of submitting it for publication.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used can be accessed at https://whoequity.shinyapps.io/heat/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study did not seek ethical clearance since the WHO HEAT software and the dataset are freely available in the public domain.

Consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Family Planning 2022: Meeting the changing needs for family planning: Contraceptive use by age and method. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 4 (https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2023/Feb/undesa_pd_2022_world-family-planning.pdf).

- 2.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Estimates and Projections of Family Planning Indicators 2022. 2022.

- 3.Cleland J, Conde-Agudelo A, Peterson H, Ross J, Tsui A. Contraception and health. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):149–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenberg C, Hellwig F, Ewerling F, Barros AJ. Socio-demographic and economic inequalities in modern contraception in 11 low-and middle-income countries: an analysis of the PMA2020 surveys. Reprod Health. 2020;17:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Population Division: www.population.un.org/dataportal/home (https://population.un.org/dataportal/home. Accessed 10 Jun 2024.

- 6.Statistics Sierra Leone—StatsSL, ICF. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2019. StatsSL/ICF; 2020.

- 7.Family Planning. UNFPA Sierra Leone. https://sierraleone.unfpa.org/en/topics/family-planning-6 2017. Accessed 10 Jun 2024.

- 8.Keen S, Begum H, Friedman HS, James CD. Scaling up family planning in Sierra Leone: a prospective cost-benefit analysis. Womens Health. 2017;13(3):43–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sierra Leone—Family planning 2030. https://www.fp2030.org/sierra-leone/ 2020. Accessed 10 Jun 2024.

- 10.Barrie HA. Determinants of contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents aged 15–19 years in Sierra Leone: an analysis of the sierra leone demographic and health surveys 2008–2019 (Doctoral dissertation, University Of Ghana). 2022.

- 11.Lakew Y, Reda AA, Tamene H, Benedict S, Deribe K. Geographical variation and factors influencing modern contraceptive use among married women in Ethiopia: evidence from a national population based survey. Reprod Health. 2013;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutumba M, Wekesa E, Stephenson R. Community influences on modern contraceptive use among young women in low and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional multi-country analysis. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, Steinauer J. Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):214–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackstone SR, Nwaozuru U, Iwelunmor J. Factors influencing contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2017;37(2):79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakirijja DS, Xuili X, Kayiso MI. Socio-economic determinants of access to and utilization of contraception among rural women in Uganda: the case of Wakiso district. Health Sci J. 2018;12(6):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sserwanja Q, Turimumahoro P, Nuwabaine L, Kamara K, Musaba MW. Association between exposure to family planning messages on different mass media channels and the utilisation of modern contraceptives among young women in Sierra Leone: insights from the 2019 Sierra Leone demographic health survey. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olal E, Grovogui FM, Nantale R, Sserwanja Q, Nakazwe C, Nuwabaine L, Mukunya D, Ikoona EN, Benova L. Trends and determinants of modern contraceptive utilisation among adolescent girls aged 15–19 years in Sierra Leone: an analysis of demographic and Health Surveys, 2008–2019. J Global Health Rep. 2023;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agbadi P, Eunice TT, Akosua AF, Owusu S. Complex samples logistic regression analysis of predictors of the current use of modern contraceptive among married or in-union women in Sierra Leone: insight from the 2013 demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4): e0231630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincon C. Women’s participation in household decision-making and modern contraceptive use among married women in Sierra Leone.

- 20.Osborne A, James PB, Bangura C, Kangbai JB. Exploring the drivers of unmet need for contraception among adolescents and young women in Sierra Leone. A cross-sectional study. Contraception Reproduct Med. 2024;9(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osborne A, Bangura C. Proximal factors influencing the likelihood of married and cohabiting women in Sierra Leone to use contraceptives. A cross-sectional study. Contraception Reproduct Med. 2024;9(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sserwanja Q, Nuwabaine L, Kamara K, Musaba MW. Determinants of quality contraceptive counselling information among young women in Sierra Leone: insights from the 2019 Sierra Leone demographic health survey. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omondi T, Sheriff ID. Sierra Leone’s long recovery from the scars of war. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:725–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sierra Leone National rmncah strategy 2017–2021. https://portal.mohs.gov.sl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/final-rmncah-strategy_may-2017-_word-doc.pdf. Accessed 24 September 2024.

- 25.Jalloh MB, Bah AJ, James PB, Sevalie S, Hann K, Shmueli A. Impact of the free healthcare initiative on wealth-related inequity in the utilization of maternal and child health services in Sierra Leone. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT). Software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. In: Built-in database edition. Version 6.0. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024.

- 27.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO. Handbook on health inequality monitoring with a special focus on low and middle-income countries. Geneva World Health Organization 2013.

- 29.Hosseinpoor AR, Nambiar D, Schlotheuber A, Reidpath D, Ross Z. Health equity assessment toolkit (HEAT): software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris JL, Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: the global challenges. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:S40–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogundele OJ, Pavlova M, Groot W. Examining trends in inequality in the use of reproductive health care services in Ghana and Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biney AA, Wright KJ, Kushitor MK, Jackson EF, Phillips JF, Awoonor-Williams JK, Bawah AA. Being ready, willing and able: understanding the dynamics of family planning decision-making through community-based group discussions in the Northern Region. Ghana Genus. 2021;77:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolarinwa OA. Inequality gaps in modern contraceptive use and associated factors among women of reproductive age in Nigeria between 2003 and 2018. BMC Womens Health. 2024;24(1):317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aviisah PA, Dery S, Atsu BK, Yawson A, Alotaibi RM, Rezk HR, Guure C. Modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Ghana: analysis of the 2003–2014 Ghana demographic and health surveys. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andi JR, Wamala R, Ocaya B, Kabagenyi A. Modern contraceptive use among women in Uganda: an analysis of trend and patterns (1995–2011). Etude De La Popul Afr. 2014;28:1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradley SE, Shiras T. Where women access contraception in 36 low-and middle-income countries and why it matters. Global Health Sci Pract. 2022;10(3):e2100525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conteh JG. Residents’ Perceptions of Healthcare Disparities in Rural Sierra Leone. Walden University; 2022.

- 38.Duminy J, Cleland J, Harpham T, Montgomery MR, Parnell S, Speizer IS. Urban family planning in low-and middle-income countries: a critical scoping review. Front Global Women Health. 2021;25(2): 749636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsawe M, Susuman AS. Inequalities in maternal Healthcare use in Sierra Leone: evidence from the 2008–2019 demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10): e0276102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.International Women’s Day—protecting reproductive rights of rural women: a pathway to a more equal world. UNFPA Sierra Leone. https://sierraleone.unfpa.org/en/news/international-womens-day-protecting-reproductive-rights-rural-women-pathway-more-equal-world. 2018. Accessed 24 September 2024.

- 41.Cooper CM, Fields R, Mazzeo CI, Taylor N, Pfitzer A, Momolu M, Jabbeh-Howe C. Successful proof of concept of family planning and immunization integration in Liberia. Global Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(1):71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caviglia M, Dell’Aringa M, Putoto G, Buson R, Pini S, Youkee D, Jambai A, Vandy MJ, Rosi P, Hubloue I, Della CF. Improving access to healthcare in Sierra Leone: the role of the newly developed national emergency medical service. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quak EJ, Tull K. Evidence of successful interventions and policies to achieve a demographic transition in sub-Saharan Africa: Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Malawi.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used can be accessed at https://whoequity.shinyapps.io/heat/.