Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction are prevalent endocrine disorders that impose enormous burdens on patients and countries. However, access to essential medicines remains inadequate in many low-income countries. This study evaluated medications’ availability, price, and affordability for these conditions.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at health facilities in the South Wollo zone in 2022. Following World Health Organization (WHO)/Health Action International (HAI) guidelines, 34 medicines were evaluated across 60 medicine outlets. Data were collected using a standardized tool adapted from WHO/HAI. Availability was measured by the percentage of facilities where the medicines were in stock. Prices were reported as median prices and median price ratios (MPR). Affordability was assessed based on the number of days’ wages required for the lowest-paid government workers to cover the full course of therapy.

Results

The availability of lowest-priced generic (LPG) diabetes and thyroid dysfunction medicines in the public sector was 24.4% and 28.7%, respectively. In private pharmacies, availability was 26.3% for diabetes and 21% for thyroid dysfunction medicines. Median prices for LPG medicines were higher in private pharmacies than in public health facilities, with 81.81% showing a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). In private pharmacies, the prices of LPG diabetes (5, 71.43%) and thyroid dysfunction medicines (5, 83.33%) exceeded the reference price. None of the LPG diabetes and thyroid dysfunction medicines were affordable in either setting.

Conclusions

The study revealed a very low availability of medicines and a financial burden on patients. Therefore, the government should improve the availability of these essential medicines and regulate their prices.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-024-11935-8.

Keywords: Availability, Affordability, Price, Medicines, Diabetes mellitus, Thyroid dysfunction

Background

Endocrine disorders include a range of medical conditions that disrupt the normal functioning of the endocrine system, responsible for producing and regulating hormones throughout the body. Diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction are the most common endocrine disorders [1].

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, stemming from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both [2]. This condition can lead to pathological and functional changes in various organs even in the absence of severe symptoms [3]. The associated risks, including cardiovascular complications, contribute to approximately 2.2 million premature deaths annually [4].

Thyroid dysfunction, the most common endocrine disorder after diabetes mellitus, involves alterations in the production of thyroid hormones. It manifests as hypothyroidism, where insufficient hormone production occurs, and hyperthyroidism, characterized by excessive hormone production by the thyroid gland [5].

Thyroid dysfunction and diabetes mellitus frequently co-occur and share overlapping pathologies [6]. Approximately 20% of diabetes patients experience thyroid dysfunction [7], compared to around 6% in the non-diabetic population [8]. The global prevalence of diabetes mellitus has been steadily increasing. In 1995, it was estimated at 4.0% (135 million), projected to rise to 5.4% (300 million) by 2025 [9], and further to 592 million by 2035 [10]. This rise is particularly pronounced in low and middle-income countries [4], where more than 75% of people with diabetes mellitus are expected to reside by 2025 [9]. In Ethiopia, the pooled prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults is estimated to be 6.5% [11]. The number of diabetic cases is projected to reach 2.6 million by 2025 [12].

The growing burden of chronic diseases and their associated complications imposes significant social and economic challenges on patients, society, and the country [4, 13]. Globally, diabetes mellitus alone accounted for more than 11.6% of total health expenditure in 2015 [14, 15]. In particular, chronic diseases present a formidable economic challenge in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) [16], where the costs associated with their management increase with age [17].

Treatment for chronic diseases remains unaffordable in many countries across World Health Organization (WHO) regions [18]. Patients are experiencing the greatest economic burden [19], with the majority of low-income individuals (93.8%) unable to afford at least one essential medicine [20]. Moreover, escalating medicine prices continue to intensify financial strain, further limiting access to essential treatments for many individuals [21].

Long-term treatment requiring continuous medication is essential for patients with diabetes and thyroid dysfunction. The WHO aims for 80% availability of essential medicines for non-communicable diseases. However, availability varies across WHO regions, with generic medicines in the public sector ranging from 29.4 to 54.4% [18]. In low and middle-income countries, insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents are often unavailable [4]. In Zambia, a majority of diabetes mellitus medicines are inadequately available [21].

Affordable and high-quality essential medicines are critical components of a well-functioning health system [22]. Understanding the availability, price, and affordability of medicines for diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction is crucial for promoting access to healthcare, supporting treatment adherence, reducing economic burdens on patients, informing policy decisions, and ultimately improving health outcomes. A few studies have assessed access to essential medicines for managing non-communicable diseases [23] and diabetes [24]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the availability, pricing, and affordability of both diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction medicines using WHO and Health Action International (HAI) methodology.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the availability, price, and affordability of medicines for diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction. The study followed a standardized methodology developed by the WHO/HAI [25].

Study area and period

The study was conducted from August 1–31, 2022, in the health facilities of the South Wollo zone, northeast of the capital, Addis Ababa. According to the 2007 Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, the South Wollo zone has a total population of 3.5 million residents. The zone comprises 22 districts (Woredas) and 2 city administrations. According to the zonal health department, 144 health centers, 14 hospitals, 55 private pharmacies, and 233 drug stores are within the zone.

The study area was selected based on the following considerations: Firstly, given Ethiopia’s vast geographic expanse, the WHO/HAI methodology recommends conducting provincial surveys or a series of provincial-based surveys [25]. Secondly, the zone serves as a hub for medical tourism, offering healthcare services to patients from neighboring areas such as the Afar region, Oromia special zone, and North Wollo zone. Thirdly, the concentration of private health facilities in the South Wollo zone made it a suitable candidate for this study.

The study was conducted in both public and private health facilities across the districts of the South Wollo Zone, including Dessie, Kombolcha, Borena, Tehuledere, Legambo, and Delanta. Dessie, the capital city of the zone, is located 430 km from Addis Ababa. The population of the city is 289,589 according to the Zonal Statistics Office. Kombolcha, a town and district in north-central Ethiopia, is 23 km from Dessie and has a population of 172,215. Borena, located 180 km from Dessie in the western part of the South Wollo Zone, has a population of 199,406. Tehuledere is another district in the zone, located 30 km from Dessie, with a population of 156,604. Legambo, located 99 km southwest of Dessie, has a population of 215,660. Delanta is located 98 km northwest of Dessie, with a population of 143,888 [26].

Population

All healthcare facilities within the South Wollo zone and all medicines available therein constituted the source population for this study. Healthcare facilities that met the criteria set by WHO/HAI guidelines were the study population. Moreover, the study population comprised medicines listed in the WHO/HAI global core list and those used for managing diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included all medicines listed in the WHO/HAI global core list [25]. Essential medicines used for managing diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction, which are listed in the WHO [27] and the Ethiopian Essential Medicine List [28] were included. Medicines not registered in Ethiopia, had incomplete records, or were provided free of cost were excluded from the study. Drug stores were excluded from the study because they did not stock the majority of the medicines.

Sample size determination

Selection of healthcare facilities

Health facilities were selected following the WHO/HAI methodology [25]. Dessie, the capital city of the zone, was chosen as the major center. From Dessie, an additional five districts namely Kombolcha, Borena, Tehuledere, Legambo, and Delanta were randomly selected, all reachable within one day’s travel. One main public hospital was chosen in each selected district and major center. Subsequently, five public health facilities (health centers) were randomly selected within a three-hour drive radius from each main hospital. This process resulted in a total of 6 hospitals and 24 health centers being included in the public sector sample. For the private sector sample, the closest five pharmacies to each selected public health facility were chosen randomly. This selection method led to a total inclusion of 30 public health facilities and 30 private pharmacies in the study.

Selection of medicines

According to the WHO/HAI guideline, price-based studies should include both global core and supplementary medicines. Global core medicines are standardized across WHO/HAI surveys, facilitating international comparisons of medicine prices, availability, and affordability [25]. The supplementary list was employed to study commonly used medicines for addressing significant national/global health issues such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction. These essential medicines were selected from standard treatment guideline [29] and essential medicine list of Ethiopia [28].

Following WHO/HAI survey guidelines, all dosage forms and strengths specified in the essential medicine list were identified for inclusion. This included both single and fixed-dose combination products, ensuring compliance with survey requirements. In total, the study included 34 different dosages or strengths of medicines, comprising 14 global core medicines, 10 for diabetes mellitus, and 10 for thyroid dysfunction (Supplementary table).

Study variables

The dependent variables included the availability, price, and affordability of medicines. The independent variables included the type of health sector (public or private), duration of therapy, monthly income of the lowest-paid government worker (converted into daily wage), and type of medicine (original brand (OB) or lowest-priced generic LPG)).

Data collection tools and procedures

A standardized data collection tool adapted from WHO/HAI was used for data collection [25]. The collected data included medicine name, brand name, strength, dosage form, pack size, and price. All data were collected at a single point in time for each health facility. Five pharmacists participated in data collection using a printed version of the data collection form, with unique identifiers assigned to each health facility. The data collectors received half a day of training based on the WHO/HAI manual. One pharmacist was assigned to collect data in each district, while all pharmacists we involved in collecting data from the major center. The collected data were thoroughly verified by the principal investigators to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Data processing and analysis

Data entry and analysis were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2016. The analysis assessed the availability, price, and affordability of medicines both overall and within specific groups.

Availability

According to WHO/HAI, availability is defined as the percentage of outlets where an individual medicine was found on the day of data collection [25]. Availability was evaluated by determining the percentage of health facilities where the surveyed medicines were accessible at the time of the survey, along with calculating the mean percentage availability across the selected medicines. In the public sector, availability was further analyzed based on the levels of care (hospitals and health centers) where the medicines were expected to be stocked. Medicine availability was categorized into levels: very low (< 30%), low (30–49%), fairly high (50–80%), and high (> 80%) [30].

Price

Medicine prices were analyzed based on the median prices of individual medicines. Additionally, it was estimated using the median price ratio (MPR). The MPR was calculated as follows.

The WHO/HAI methodology recommended the International Medical Products Price Guide from Management Sciences for Health (MSH) as the source for international reference prices [25]. However, this guide was not updated after 2015. To address this, both the WHO/HAI guideline [25] and HAI [31] suggest using alternative sources for reference prices that offer more current data. For this study, the South African Government Medicines Price Registry was adopted as the source for reference prices [32]. Local currency prices (Birr) and South African currency (Rand) were converted into United States Dollars (USD) using the average exchange rate during the data collection period to standardize comparisons. Gelders et al. criteria were used to classify the MPR. Medicines with an MPR of 1.5 or less were considered acceptable [30].

For medicines where matching prices were identified, a price comparison was conducted between the MPR of OB products and the MPR of LPG, calculated using the following formula [25]: MPROB / MPRLPG.

Affordability

According to WHO/HAI [25], drug affordability is defined as the ability to pay for a course of treatment, measured by the daily wages of the lowest-paid unskilled government worker. The affordability of medicines assessed the ability of the lowest-paid unskilled government workers to pay for the full course of therapy, spanning 7 days for acute conditions and 30 days for chronic conditions [25]. It was estimated as follows.

The total cost of medicines was calculated by multiplying the daily defined dose, the number of days in the treatment course, and the median price. The daily defined dose of medicines was determined based on the WHO prescribed daily dose [33]. The daily wage of Ethiopia’s lowest-paid unskilled government worker is 0.44 Dollars (https://mywage.org/ethiopia/labour-law/wages). Affordability is evaluated by comparing the number of days’ wages required to pay for treatment with the daily wage of the lowest-paid unskilled government worker [34]. Medicines costing less than the daily wage of unskilled government workers are considered affordable, while those costing equal to or more than the daily wage are deemed unaffordable [25].

The price difference between public and private health facilities was assessed using a t-test for data with a normal distribution and a Mann-Whitney U test for data with a non-normal distribution. Normality and homogeneity of variances were tested, with significance set at a p-value < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29 (IBM, USA).

Results

Availability of medicines

Table 1 shows the availability of surveyed medicines. None of the OB medications were found in public health facilities. In private pharmacies, the overall pooled availability of OBs was 6.27%, ranging from 2 (6.67%) to 12 (40%). The only available thyroid dysfunction OB medicine was Propranolol 40 mg tablets. The available OB diabetes medicines included Glibenclamide 5 mg tablets (9, 30%), Metformin 850 mg tablets (2, 6.67%), Glimepiride 1 mg tablets (4, 13.34%), and Glimepiride 2 mg tablets (10, 33.34%).

Table 1.

Availability of medicines in health facilities of South Wollo zone, 2022

| Medicine, strength, dosage form | Lowest price generics | Originator brand | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public health facilities | Private | Private | |||

| Hospital (n = 6) | Health centre (n = 24) | Total (n = 30) | Pharmacy (n = 30) | Pharmacy (n = 30) | |

| Salbutamol 0.1 mg/dosea | 5(83.33) | 16(66.67) | 21(70) | 18(60) | 12(40) |

| Atenolol 50 mg tableta | 5(83.33) | 10(41.67) | 15(50) | 25(83.33) | 0(0) |

| Captopril 25 mg tableta | 4(66.67) | 0(0) | 4(13.33) | 5(16.67) | 2(6.67) |

| Simvastatin 20 mg tableta | 4(66.67) | NA | 4(13.33) | 8(26.67) | 2(6.67) |

| Amitriptyline 25 mg tableta | 5(83.33) | 14(58.33) | 19(63.33) | 28(93.33) | 2(6.67) |

| Ciprofloxacin 500 mg tableta | 5(83.33) | 16(66.67) | 21(70) | 18(60) | 4(13.33) |

| Co-trimoxazole 8 + 40 mg/mL suspensiona | 6(100) | 17(70.83) | 23(76.67) | 23(76.67) | 6(20) |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg capsulea | 6(100) | 16(66.67) | 22(73.33) | 24(80) | 2(6.67) |

| Ceftriaxone 1 g/vial injectiona | 6(100) | 17(70.83) | 23(76.67) | 28(93.33) | 0(0) |

| Diazepam 5 mg tableta | 5(83.33) | 9(37.5) | 14(46.67) | 11(36.67) | 0(0) |

| Diclofenac 50 mg tableta | 6(100) | 17(70.83) | 23(76.67) | 25(83.33) | 0(0) |

| Paracetamol 120 mg/5 ml suspensiona | 6(100) | 19(79.17) | 25(83.33) | 26(86.67) | 7(23.33) |

| Omeprazole 20 mg capsulea | 6(100) | 18(75) | 24(80) | 24(80) | 0(0) |

| Glibenclamide 5 mg tableta | 5(83.33) | 10(41.67) | 15(50) | 20(66.67) | 9(30) |

| Metformin 500 mg tabletb | 5(83.33) | 8(33.33) | 13(43.33) | 19(63.33) | 0(0) |

| Metformin 850 mg tabletb | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 6(20) | 2(6.67) |

| Biphasic Isophane Insulin (Soluble/Isophane mixture, 30/70, 100 unit/vial)b | 5(83.33) | 6(25) | 11(36.67) | 14(46.67) | 0(0) |

| Insulin Soluble / Neutral 100 unit/vialb | 4(66.67) | 6(25) | 10(33.33) | 12(40) | 0(0) |

| Isophane/NPH Insulin 100 unit/vialb | 5(83.33) | 5(20.83) | 10(33.33) | 13(43.33) | 0(0) |

| Glimepride 1 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 6(20) | 4(13.33) |

| Glimepride 2 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 9(30) | 10(33.33) |

| Gliclazide 30 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Gliclazide 30 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Dapagliflozin 10 mg tableb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Iodine + Potassium Iodide 5% + 10% solutionb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 3(10) | 0(0) |

| Carbimazole 5 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 3(10) | 0(0) |

| Propylthiouracil 25 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 2(6.67) | 0(0) |

| Propylthiouracil 50 mg tabletb | 2(33.33) | NA | 2(6.67) | 4(13.33) | 0(0) |

| Propylthiouracil 100 mg tabletb | 4(66.67) | NA | 4(13.33) | 14(46.67) | 0(0) |

| Levothyroxine 0.025 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 2(6.67) | 0(0) |

| Levothyroxine 0.5 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 2(6.67) | 0(0) |

| Levothyroxine 0.1 mg tabletb | 0(0) | NA | 0(0) | 4(13.33) | 0(0) |

| Propranolol 10 mg tabletb | 4(66.67) | 7(29.17) | 11(36.67) | 14(46.67) | 0(0) |

| Propranolol 40 mg tabletb | 5(83.33) | 9(37.5) | 14(46.67) | 15(50) | 2(6.67) |

| Total | 108 | 220 | 328 | 425 | 64 |

| Maximum expected | 204 | 480 | 684 | 1020 | 1020 |

| Overall average (pooled) | 52.94 | 45.83 | 47.95 | 41.77 | 6.27 |

NA: medicines expected to be stocked by hospital only

aGlobal core list of medicines

bSupplementary list of medicines

The overall percent availability of LPGs was 47.95% in public health facilities and 41.67% in private pharmacies. Except for Captopril 25 mg tablet, all LPG global core medicines were available in more than 50% of surveyed public health facilities. The available LPG diabetes medications were Glibenclamide 5 mg tablets (15, 50%), Metformin 500 mg tablets (13, 43.33%), Biphasic Isophane Insulin (11, 36.67%), Insulin Soluble / Neutral (10, 33.34%), and Isophane/NPH Insulin (10, 33.34%). Regarding thyroid dysfunction treatments, the available medications included Propylthiouracil 50 mg tablets (2, 6.67%), Propylthiouracil 100 mg tablets (4, 13.33%), Propranolol 10 mg tablets (11, 36.67%), and Propranolol 40 mg tablets (14, 46.67%). Among LPGs in private pharmacies, 14 (41.18%) were available in more than 50% of surveyed locations. The highest availability (28, 93.33%) was for Amitriptyline 25 mg tablet and Ceftriaxone 1 g/vial injection.

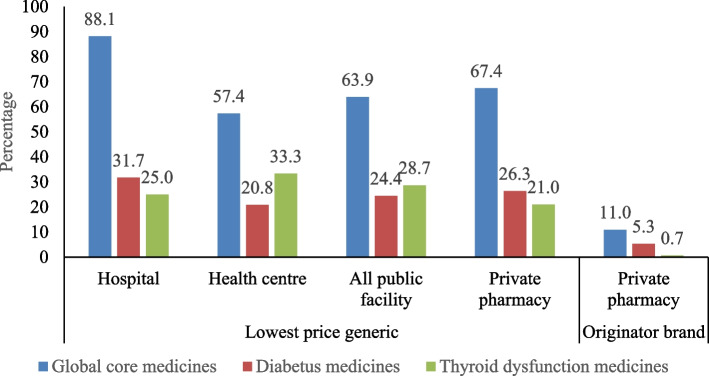

The availability of LPG global core medicines, diabetes medicines, and thyroid dysfunction medicines in public health facilities was 63.9%, 24.4%, and 28.7%, respectively (Fig. 1). Generally, the mean availability of sampled medicines was higher in public hospitals compared to health centers, except for thyroid dysfunction medicines. The generic product availability was higher in private pharmacies than in public facilities, except for thyroid dysfunction medicines. In private pharmacies, the availability of OBs global core medicines, diabetes medicines, and thyroid dysfunction medicines was 11%, 5.3%, and 0.7%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Availability of medicine in health facilities of South Wollo zone, 2022

Price of medicines

Table 2 presents the median prices (USD) of medicines along with their 25th and 75th percentiles. The median prices of LPG medicines were higher in private pharmacies compared to public health facilities. Specifically, 18 medicines (81.81%) exhibited a statistically significant difference. The median prices of Atenolol 50 mg tablets, Captopril 25 mg tablets, Simvastatin 20 mg tablets, Amitriptyline 25 mg tablets, Ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablets, Amoxicillin 500 mg capsules, Ceftriaxone 1 g/vial injections, Diazepam 50 mg tablets, Diclofenac 50 mg tablets, Omeprazole 20 mg capsules, Glibenclamide 5 mg tablets, Metformin 500 mg tablets, and Propranolol 40 mg tablets in the private sector were more than double than those in the public sector.

Table 2.

The median price (USD) of medicines in health facilities of South Wollo zone, 2022

| Medicine, strength, dosage form | Lowest price generics | Originator brand | Comparison between public and private LPG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public health facilities | Private pharmacy | Private pharmacy | ||||||||

| Median | 25th | 75th | Median | 25th | 75th | Median | 25th | 75th | P-value | |

| Salbutamol 0.1 mg/dose | 2.23 | 1.68 | 2.74 | 2.91 | 1.91 | 4.55 | 4.16 | 2.57 | 6.10 | 0.26 |

| Atenolol 50 mg tablet | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.01 | |||

| Captopril 25 mg tablet | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Simvastatin 20 mg tablet | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.06 |

| Amitriptyline 25 mg tablet | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.01 |

| Co-trimoxazole 8 + 40 mg/mL suspension | 0.58 | 0.27 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 1.24 | 0.95 | 1.53 | 0.01 |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg capsule | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Ceftriaxone 1 g/vial injection | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.01 | |||

| Diazepam 50 mg tablet | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.01 | |||

| Diclofenac 50 mg tablet | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |||

| Paracetamol 120 mg/5 ml suspension | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 1.25 | 0.76 | 1.64 | 0.01 |

| Omeprazole 20 mg capsule | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Glibenclamide 5 mg tablet | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.01 |

| Metformin 500 mg tablet | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |||

| Metformin 850 mg tablet | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.25 | ||||

| Biphasic Isophane Insulin (Soluble/Isophane mixture, 30/70, 100U/vial) | 2.50 | 2.13 | 2.81 | 4.08 | 2.86 | 5.24 | 0.01 | |||

| Insulin Soluble / Neutral 100u/ml/vial | 2.33 | 2.24 | 2.41 | 3.49 | 2.83 | 3.57 | 0.005 | |||

| Isophane/NPH Insulin 100u/ml/vial | 2.42 | 2.23 | 2.71 | 3.50 | 2.95 | 4.12 | 0.01 | |||

| Glimepride 1 mg tablet | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.33 | ||||

| Glimepride 2 mg tablet | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.37 | ||||

| Iodine + Potassium Iodide 5% + 10% solution | 1.47 | 1.14 | 1.62 | |||||||

| Carbimazole 5 mg tablet | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.22 | |||||||

| Propylthiouracil 25 mg tablet | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Propylthiouracil 50 mg tablet | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.57 | |||

| Propylthiouracil 100 mg tablet | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.11 | |||

| Levothyroxine 0.025 mg tablet | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.13 | |||||||

| Levothyroxine 0.1 mg tablet | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Levothyroxine 0.5 mg tablet | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.18 | |||||||

| Propranolol 10 mg tablet | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.006 | |||

| Propranolol 40 mg tablet | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

In public health facilities, the prices of 7 (36.94%) LPG medicines exceeded the reference price. Among these, three were global core medicines, three were diabetes medicines, and one was a thyroid dysfunction medicine. In private pharmacies, the prices of LPG global core medicines (4, 28.57%), diabetes medicines (5, 71.43%), and thyroid dysfunction medicines (5, 83.33%) were higher than the reference price. Additionally, all OB medicines, except Simvastatin 20 mg tablets, had prices higher than the reference price in private pharmacies. The OB products were about 2.18 times more expensive than LPG equivalents in private pharmacies (Table 3).

Table 3.

MPR of medicines in health facilities of South Wollo zone, 2022

| Medicine, strength, dosage form | LPG | OB | MPROB/MPRLPG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public health facilities | Private pharmacy | Private pharmacy | ||

| Salbutamol 0.1 mg/dose | 1.13 | 1.48 | 2.11 | 1.43 |

| Atenolol 50 mg tablet | 0.49 | 2.25 | ||

| Captopril 25 mg tablet | 0.32 | 0.86 | 3.39 | 3.95 |

| Simvastatin 20 mg tablet | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 1.88 |

| Amitriptyline 25 mg tablet | 0.05 | 0.68 | 1.33 | 1.96 |

| Ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet | 0.16 | 0.43 | 1.79 | 4.16 |

| Co-trimoxazole 8 + 40 mg/mL suspension | 1.73 | 2.61 | 3.67 | 1.41 |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg capsule | 0.44 | 0.99 | 1.88 | 1.89 |

| Ceftriaxone 1 g/vial injection | 0.25 | 0.62 | ||

| Diazepam 5 mg tablet | 1.96 | 10.18 | ||

| Diclofenac 50 mg tablet | 0.06 | 0.31 | ||

| Paracetamol 120 mg/5 ml suspension | 5.71 | 10.63 | 1.81 | 1.67 |

| Omeprazole 20 mg capsule | 0.05 | 0.11 | ||

| Glibenclamide 5 mg tablet | 0.05 | 0.27 | 1.21 | 4.50 |

| Metformin 500 mg tablet | 0.27 | 0.95 | ||

| Metformin 850 mg tablet | 3.68 | 5.57 | 1.51 | |

| Biphasic Isophane Insulin (Soluble/Isophane mixture, 30/70, 100U/vial) | 1.14 | 1.87 | ||

| Insulin Soluble / Neutral 100u/ml/vial | 1.19 | 1.77 | ||

| Isophane/NPH Insulin 100u/ml/vial | 1.09 | 1.57 | ||

| Glimepride 1 mg tablet | 2.04 | 2.51 | 1.23 | |

| Glimepride 2 mg tablet | 1.24 | 1.48 | 1.19 | |

| Carbimazole 50 mg tablet | 0.52 | |||

| Levothyroxine 0.025 mg tablet | 2.84 | |||

| Levothyroxine 0.1 mg tablet | 2.51 | |||

| Levothyroxine 0.5 mg tablet | 2.22 | |||

| Propranolol 10 mg tablet | 2.20 | 4.02 | ||

| Propranolol 40 mg tablet | 0.86 | 7.78 | 11.67 | 1.50 |

Affordability of medicines

The affordability of essential LPG medicines varied between public health facilities and private pharmacies. Specifically, while the percentage of affordable global core LPG medicines was 35.71% in public health facilities, it dropped to 7.14% in private pharmacies. On average, it took 4.4 days of wages to purchase medicines in public health facilities, and 14.4 days of wages in private pharmacies. None of the LPG diabetes and thyroid dysfunction medicines were deemed affordable in either setting. In public health facilities, top unaffordable medicines included Propranolol 10 mg tablet, Propylthiouracil 50 mg, and Propylthiouracil 100 mg tablet, each requiring 17.67, 14.03, and 9.25 days’ wages of the lowest-paid government employee, respectively. In private pharmacies, the most unaffordable LPG medicines for diabetes and thyroid dysfunction were the Metformin 850 mg tablet and Levothyroxine 0.025 mg tablet, which required 22.74 and 52.63 days’ wages of the lowest-paid government employee, respectively. Notably, all OB medicines in private pharmacies were found to be unaffordable (Table 4).

Table 4.

Affordability of medicines in health facilities of South Wollo zone, 2022

| Medicine, strength, dosage form | Daily defined dose | Number of units | Number of days | Total dose | LPG | OB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public health facilities | Private pharmacy | Private pharmacy | |||||

| Salbutamol 0.1 mg/dose | 0.8 mg | 8 dose | 30 | 1 | 5.07 | 6.62 | 9.46 |

| Atenolol 50 mg tablet | 75 mg | 1.5 tab | 30 | 45 | 2.09 | 9.51 | |

| Captopril 25 mg tablet | 50 mg | 2 tab | 30 | 60 | 1.64 | 4.44 | 17.54 |

| Simvastatin 20 mg tablet | 30 mg | 1.5 tab | 30 | 45 | 5.95 | 15.63 | 29.39 |

| Amitriptyline 25 mg tablet | 75 mg | 3 tab | 30 | 90 | 2.03 | 26.90 | 52.63 |

| Ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet | 1 g | 2 tab | 7 | 14 | 0.73 | 1.95 | 8.10 |

| Co-trimoxazole 8 + 40 mg/mL suspension | 5 ml | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1.33 | 2.01 | 2.82 |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg capsule | 1.5 g | 3 cap | 7 | 21 | 1.52 | 3.39 | 6.41 |

| Ceftriaxone 1 g/vial injection | 2 g | 2 vial | 7 | 14 | 9.53 | 23.93 | |

| Diazepam 5 mg tablet | 10 mg | 2 tab | 7 | 14 | 0.50 | 2.58 | |

| Diclofenac 50 mg tablet | 0.1 g | 2 tab | 7 | 14 | 0.27 | 1.47 | |

| Paracetamol 120 mg/5 ml suspension | 1 | 0.91 | 1.70 | 2.85 | |||

| Omeprazole 20 mg capsule | 20 mg | 1 cap | 7 | 7 | 0.27 | 0.59 | |

| Glibenclamide 5 mg tablet | 10 mg | 2 tab | 30 | 60 | 1.46 | 8.24 | 37.09 |

| Metformin 500 mg tablet | 2 g | 4 tab | 30 | 120 | 3.07 | 10.97 | |

| Metformin 850 mg tablet | 2 g | 2 tab | 30 | 60 | 22.74 | 34.44 | |

| Biphasic Isophane Insulin (Soluble/Isophane mixture, 30/70, 100U/vial) | 40 | 40 | 30 | 1 | 5.69 | 9.27 | |

| Insulin Soluble / Neutral 100u/ml/vial | 40 | 40 | 30 | 1 | 5.30 | 7.93 | |

| Isophane/NPH Insulin 100u/ml/vial | 40 | 40 | 30 | 1 | 5.51 | 7.95 | |

| Glimepride 1 mg tablet | 2 mg | 2 tab | 30 | 60 | 33.50 | 41.27 | |

| Glimepride 2 mg tablet | 2 mg | 1 tab | 30 | 30 | 20.21 | 24.04 | |

| Iodine + Potassium Iodide 5% + 10% solution | 1 ml | 3 | 10 | 1 | 3.35 | ||

| Carbimazole 5 mg tablet | 15 mg | 3 tab | 30 | 90 | 41.28 | ||

| Propylthiouracil 25 mg tablet | 0.1 g | 4 tab | 30 | 120 | 27.70 | ||

| Propylthiouracil 50 mg tablet | 0.1 g | 2 tab | 30 | 60 | 14.03 | 16.24 | |

| Propylthiouracil 100 mg tablet | 0.1 g | 1 tab | 30 | 30 | 9.25 | 11.12 | |

| Levothyroxine 0.025 mg tablet | 0.15 mg | 6 tab | 30 | 180 | 52.63 | ||

| Levothyroxine 0.1 mg tablet | 0.15 mg | 1.5 tab | 30 | 45 | 15.24 | ||

| Levothyroxine 0.5 mg tablet | 0.15 mg | 0.3 tab | 30 | 9 | 3.65 | ||

| Propranolol 10 mg tablet | 0.16 g | 16 tab | 30 | 480 | 17.67 | 32.23 | |

| Propranolol 40 mg tablet | 0.16 g | 4 tab | 30 | 120 | 2.29 | 20.79 | 31.19 |

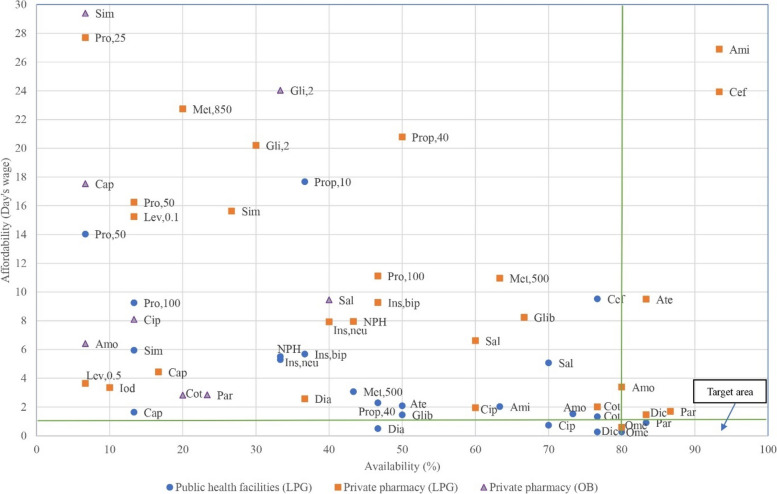

Figure 2 presents the WHO targets for the availability and affordability of medicines. The LPG of Paracetamol 120 mg/5 ml suspension and Omeprazole 20 mg capsules achieved the target availability of 80%, costing less than one day’s wage of the lowest-paid government employee in public health facilities. In private pharmacies, the LPG of Omeprazole 20 mg capsules also met the targets for availability and affordability.

Fig. 2.

Target availability and affordability of medicines in health facilities of South Wollo zone, 2022

Originator brand private pharmacy (affordability, availability) Ami (52.36, 6.67), glib (37.09, 30), Met 850 (34.44, 6.67), Gli 1 (41.27,13.33), Prop 40 (31.19, 6.67), Lowest price generic private pharmacy Glin 1 (33.5, 20), Car (41.28, 10), Lev 0.025 (52.63, 6.67), Prop 10 (32.23, 46.67).

Discussion

This study employed the WHO/HAI methodology to assess the availability, price, and affordability of diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction medications across 30 private and 30 public health facilities. Key findings include 1) a very low availability of LPG and OB diabetes and thyroid dysfunction medicines in public health facilities, 2) higher median prices observed for LPG medications in private pharmacies compared to public health facilities, 3) three diabetes mellitus and one thyroid dysfunction LPG medication were priced above the reference level, and 4) all LPG diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction medications were unaffordable in both settings.

The availability of LPG medicines for diabetes in public health facilities was 24.44%, while for thyroid dysfunction, it was 28.7%. These findings are consistent with a study conducted in central Ethiopia, where the availability of LPG diabetes medicines was 34.6% [24]. In Southern Ethiopia, essential medicines for noncommunicable diseases were available for 18.7% [23]. Similarly, the results of the present study align with findings from studies in Zambia and China, where more than 80% of essential medicines were inadequately available [21, 35]. Across WHO regions, the average availability of generic medicines in the public sector ranged from 29.4 to 54.4% [18]. Only two African countries have achieved the WHO’s global action plan target of 80% availability for essential medicines [36], and just three countries meet the target for isophane human insulin availability [4, 37, 38]. The inadequate availability of medicine may result from insufficient funding, limited local manufacturing capacity, and deficiencies in pharmaceutical logistics management systems.

The present study revealed the low availability of OB medicines. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in central Ethiopia, where the availability of OB diabetes medicines was 2.5% [24]. A study in China reported a mean availability of 34.3% for OB oral antidiabetic medicines in public hospitals [39]. A comparable finding was observed in the Lahore division, which falls below the WHO’s global action plan target for the availability of essential medicines [40]. The availability of OB medicines is crucial when LPG medicines are not accessible. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that at least one of each core medicine is available, preferably LPGs, as they are typically more affordable.

The WHO set a target of achieving 80% availability of essential medicines by 2025 to reduce premature mortality from chronic non-communicable diseases [41]. However, the availability of essential medicines for treating these diseases remains suboptimal in middle and lower-income countries [42]. The lack of medicine availability contributes to the poor prognosis experienced by people with chronic diseases [43]. Particularly in developing countries, many diabetes-related deaths are attributed to conditions that could be effectively managed with readily available medications [44, 45]. In sub-Saharan Africa, individuals with diabetes mellitus often face premature mortality due to inadequate access to insulin [36].

Access to essential medicines is recognized as a fundamental human right. Various factors affect the accessibility of medicines, including the selection of medications, their pricing, the effectiveness of healthcare systems, and the rational use of medicines [46]. The WHO has introduced a comprehensive framework to enhance access to essential medicines to tackle these challenges, thereby advancing universal health coverage by 2030. This framework includes four key components: rational selection of medicines, sustainable financing mechanisms, robust health systems, and ensuring medicines are priced affordably [47].

This study found that the median prices of medicines in private pharmacies were higher compared to those in public health facilities. Similarly, the prices of medicines were also higher in private facilities in central [24] and southern Ethiopia [23]. Private pharmacies operate in a competitive market influenced by supply and demand dynamics, where they must cover costs like rent, utilities, and staffing. Public facilities benefit from bulk procurement and government subsidies, allowing them to offer lower-price medicines. In contrast, private pharmacies incur higher procurement costs and apply markups to cover expenses and generate profit.

The MPRs of the surveyed medicines exceeded the stipulated threshold of ≤ 1.5. Previous surveys have corroborated these findings [21, 35, 39, 48–50], highlighting variability among individual medicines despite using different international price references to estimate MPR. In this study, the South African government procurement price was used, contrasting with previous surveys that employed references such as the Management Sciences for Health [21, 35, 39, 48] and Australia Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (49, 50). These differences underscore the diverse factors influencing MPRs, including country-specific conditions such as medicine prices, procurement systems, currency strength, and the timing of studies [21]. The high MPRs observed in this study reflect substantial fluctuations in foreign currency exchange rates, the depreciation of the Ethiopian local currency, and the absence of legal or regulatory frameworks governing medicine pricing in the private sector.

The OB products were about 2.18 times more costly than their LPG equivalents in private pharmacies. Despite the increasing costs of treatment and limited evidence of OBs’ therapeutic advantages, there is a growing trend towards their prescription [4]. Conversely, when biosimilar products were accessible, LPG was generally more economical than originators [37]. The WHO advocates for generic prescribing, underscoring the importance of enhancing the availability of LPG to bolster the generic prescribing system [40].

All of the LPG diabetes mellitus or thyroid dysfunction medicines were unaffordable in both private and public sectors. Similarly, all OB medicines in the private sector were unaffordable. In central Ethiopia, 58.8% of LPG diabetes medicines were unaffordable in private facilities, while 84.6% were unaffordable in public facilities [24]. In southern Ethiopia, the overall unaffordability of medicines for noncommunicable diseases was 100% [23]. Previous surveys have reported the unaffordability of treatment in Zambia [21], Pakistan [40], and China [35, 39]. The high prices of these medicines made them unaffordable for several patients, particularly those with low incomes [50]. For example, patients with low income would have to work for 4 to 7 days to afford a single vial of human or analog insulin [37]. Therefore, diabetic patients in most African countries face higher monthly out-of-pocket expenses [51]. The persistent financial burden of managing diabetes poses substantial challenges in LMICs [16], where 72.1% of patients who cannot afford medications experience poor glycemic control [20]. These challenges are also evident in Ethiopia, where they contribute to patients discontinuing treatment [52].

The inadequate treatment of chronic diseases can lead to long-term organ damage and failure [3], resulting in significant economic and social burdens for patients and their families [4]. Challenges escalate when monotherapy proves insufficient, exacerbating the affordability issue [13, 53]. The availability of generic versions of medications can lower financial barriers and enhance universal access to essential treatments [54]. Promoting generic prescribing and exploring alternative financing mechanisms are critical steps toward increasing availability and improving affordability [18]. For example, in China, the affordability of drugs in both urban and rural areas increased by 35.5% and 12.9%, respectively, following insurance reimbursement initiatives [35].

Strengths and limitations of the study

The use of the validated WHO/HAI methodology allows for the standardized assessment of the price, availability, and affordability of medicines. The study also included a WHO global core list of medicines for international comparison. However, the study is not without limitations. First, the study was conducted in the South Wollo zone, which may not fully represent the entire country. Second, the study used the South African Government pharmaceutical procurement price as a reference due to the absence of updated international reference prices, potentially affecting the accuracy of price comparison. Third, the affordability estimation only takes into account medicine prices and does not include other costs such as insulin syringes and glucometers. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of the study means that it indicates the price, availability, and affordability of medicines at a single point in time. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to other settings.

Conclusion

The availability of medicines for diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction was very low in both public and private health facilities. In private pharmacies, the median prices of LPG medicines exceeded those in public health facilities. Additionally, OB products were priced at more than twice the cost of their LPG equivalents in private pharmacies. The MPRs of the surveyed medicines surpassed the stipulated threshold of ≤ 1.5. Notably, none of the LPG medicines for diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction were affordable in either sector. Similarly, all OBs were deemed unaffordable in the private sector. Ensuring a steady supply of these essential medicines is crucial for effective disease management. Recommendations include collaborative efforts between the government and stakeholders to enhance medicine availability. Furthermore, measures should be implemented to regulate medicine prices, particularly within the private sector.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge data collectors.

Abbreviations

- HAI

Health Action International

- LMICs

Low and middle-income countries

- LPG

Lowest Price Generic

- MSH

Management Sciences for Health

- MPR

Median Price Ratio

- OB

Originator Brand

- USD

United States Dollars

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

Solomon Ahmed Mohammed: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review, and editing. Haile Yirga Mengesha: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Abel Andualem: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Elham Seid: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Getnet Mengistu Assefa: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available within the paper.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Review Committee of Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS 660/14) approved this research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ogbera AO, Kuku SF. Epidemiology of thyroid diseases in Africa. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2011;15(Suppl2):S82-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti KGMM, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hailu S, Rockers PC, Vian T, Onyango M, Laing R, Wirtz VJ. Access to diabetes medicines at the household level in eight counties of Kenya. J Diabetol. 2018;9(2):45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. World health organization global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 5.Vanderpump MP, Tunbridge WMG. The epidemiology of thyroid diseases. Werner Ingbar’s Thyroid. 2005;9:398–406. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C. The relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus and related thyroid diseases. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:390534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadgu R, Worede A, Ambachew S. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction and associated factors among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, 2000–2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2024;13(1):119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed AA, Mohamed SB, Elmadi SA, Abdorabo AA, Ismail IM, Ismail AM. Assessment of thyroid dysfunctions in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Surman, Western-Libya. Int J Clin Exp Med Sci. 2017;3:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(9):1414–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):137–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeru MA, Tesfa E, Mitiku AA, Seyoum A, Bokoro TA. Prevalence and risk factors of type-2 diabetes mellitus in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watkins P, Alemu S. Delivery of diabetes care in rural Ethiopia: an experience from Gondar. Ethiop Med J. 2003;41(1):9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Susan D, Beulens JW, Yvonne T, van der Grobbee S, Nealb DE. The global burden of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehab. 2010;17(1suppl):s3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang P, Zhang X, Brown J, Vistisen D, Sicree R, Shaw J, et al. Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(3):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Internasional Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation. 2015. https://www.idf.org/e-library/../diabetes-atlas/13-diabetes-atlas-seventh-edition.html.

- 16.Moucheraud C, Lenz C, Latkovic M, Wirtz VJ. The costs of diabetes treatment in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4(1):e001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Köster I, Von Ferber L, Ihle P, Schubert I, Hauner H. The cost burden of diabetes mellitus: the evidence from Germany—the CoDiM study. Diabetologia. 2006;49(7):1498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9659):240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bansode B, Jungari S. Economic burden of diabetic patients in India: a review. Diab Metabol Syndr. 2019;13(4):2469–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdulganiyu G, Fola T. Poverty, Affordability of Anti-Diabetic Drugs and Glycemic Control: An Unholy Alliance in a Developing Economy. Internafional Journal of Pharma Sciences and Research (IJPSR). 2013;4:113 − 20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser AH, Hehman L, Forsberg BC, Simangolwa WM, Sundewall J. Availability, prices and affordability of essential medicines for treatment of diabetes and hypertension in private pharmacies in Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations Development Group. Indicators for monitoring the millennium development goals: definitions, rationale, concepts and sources. New York. United Nations, 2003. Available at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/Indicators_for_Monitoring_the_MDGs.pdf.

- 23.Asmamaw G, Shimelis T, Tewuhibo D, Bitew T, Ayenew W. Access to essential medicines used in the management of noncommunicable diseases in Southern Ethiopia: analysis using WHO/HAI methodology. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12:20503121241266320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deressa HD, Abuye H, Adinew A, Ali MK, Kebede T, Habte BM. Access to essential medicines for diabetes care: availability, price, and affordability in central Ethiopia. Global Health Res Policy. 2024;9(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Measuring medicine prices, availability, affordability and price components. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.South Wollo Zone Statistics Office. Population of South Wollo Zone. Dessie, 2021.

- 27.World Health Organization. WHO model list of essential medicines-22nd list. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2021.02.

- 28.Ethiopian Food and Drug Authority. Ethiopian Essential Medicines List. Six editions. Addis Abeba, 2020. Available at: http://www.efda.gov.et/publication/ethiopian-essential-medicines-list-sixth-edition-2020/?lang=amh.

- 29.Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority of Ethiopia. Standard treatment guideline for general hospital. Third Edition. Addis Ababa, 2014. Available at: https://www.pascar.org/uploads/files/Ethiopia_-_General_Hospital_CPG.PDF.

- 30.Gelders S, Ewen M, Noguchi N, Laing R. Price, availability and affordability. An international comparison of chronic disease medicines. Cairo: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. 2006. Available at: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa560.pdf.

- 31.Health Action International, Collecting evidence on medicine price and availability. Available https://haiweb.org/what-we-do/price-availability-affordability/collecting-evidence-on-medicine-prices-availability/. Accessed 9 June 2024.

- 32.South African Medicine Price Registry. Available at: http://www.mpr.gov.za/.

- 33.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD index. Oslo, Norway. Available at: https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/.

- 34.Auditable Pharmaceutical Transactions and Services Trainers’ Guide, last version. 2018. Available at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2018/07/26/378000.full.pdfT.

- 35.Gong S, Cai H, Ding Y, Li W, Juan X, Peng J, et al. The availability, price and affordability of antidiabetic drugs in Hubei Province, China. Health Policy Plann. 2018;33(8):937–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fralick M, Jenkins AJ, Khunti K, Mbanya JC, Mohan V, Schmidt MI. Global accessibility of therapeutics for diabetes mellitus. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2022;18(4):199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ewen M, Joosse H-J, Beran D, Laing R. Insulin prices, availability and affordability in 13 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4(3):e001410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satheesh G, Unnikrishnan M, Sharma A. Challenges constraining availability and affordability of insulin in Bengaluru region (Karnataka, India): evidence from a mixed-methods study. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2019;12(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang C, Hu S, Zhu Y, Zhu W, Li Z, Fang Y. Evaluating access to oral anti-diabetic medicines: a cross-sectional survey of prices, availability and affordability in Shaanxi Province, Western China. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0223769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saeed A, Saeed H, Saleem Z, Fang Y, Babar ZUD. Evaluation of prices, availability and affordability of essential medicines in Lahore Division, Pakistan: A cross-sectional survey using WHO/HAI methodology. PloS one. 2019;14(4):e0216122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- 42.Khatib R, McKee M, Shannon H, Chow C, Rangarajan S, Teo K, et al. Availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their effect on use in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: an analysis of the PURE study data. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ambachew Y, Kahsay S, Tesfay R, Tesfahun L, Amare H, Mehari A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus among patients visiting medical outpatient department of Ayder Referral Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia: three years pooled. Int J Pharma Sci Res. 2015;6(02):435–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization. Priority medicines for mothers and children 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kondro W. Priority medicines for maternal and child health. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(7):E371. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hinsch M, Kaddar M, Schmitt S. Enhancing medicine price transparency through price information mechanisms. Globalization Health. 2014;10(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Equitable access to essential medicines: a framework for collective action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- 48.World Health Organization. Price, availability and affordability: an international comparison of chronic disease medicines. Geneva, 2006. Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/116493.

- 49.Wang L, Dai L, Liu H, Dai H, Li X, Ge W. Availability, affordability and price components of insulin products in different-level hospital pharmacies: evidence from two cross-sectional surveys in Nanjing, China. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0255742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Z, Feng Q, Kabba JA, Yang C, Chang J, Jiang M, et al. Prices, availability and affordability of insulin products: a cross-sectional survey in Shaanxi Province, western China. Tropical Med Int Health. 2019;24(1):43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Internasional Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation. 2013. Available at: https://www.diabete.qc.ca/en/understand-diabetes/resources/.../IDF-DA-8e-EN-finalR3.pdf.

- 52.Feleke Y, Enquselassie F. An assessment of the health care system for diabetes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19(3):203–10. [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Mourik MS, Cameron A, Ewen M, Laing RO. Availability, price and affordability of cardiovascular medicines: a comparison across 36 countries using WHO/HAI data. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010;10(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor SI. The high cost of diabetes drugs: disparate impact on the most vulnerable patients. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(10):2330–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available within the paper.