Abstract

Background

Informant discrepancies in physical activity parenting practices (PAPP) are prevalent, but their effect on adolescent physical activity (PA) remains underexplored. This study aims to examine the relationship between the (in)congruence in the parent-adolescent reports of PAPP and adolescent physical activity (PA).

Methods

Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect perceptions on nine types of PAPP and adolescents’ PA levels from 373 Chinese parent-adolescent dyads. Multiple linear regression, polynomial regression, and Response Surface Analysis were employed to explore the relationship between parent-adolescent (in)congruence in PAPP reports and adolescent physical activity.

Results

Over half of the dyads exhibited incongruence in their PAPP reports, with parents generally reporting higher PAPP scores compared to adolescents. Neither parent-reported nor adolescent-reported punishment, pressuring, and restriction were significantly associated adolescent PA. In contrast, adolescent-reported disengagement, expectation, facilitation, monitoring, non-directive support, and autonomy support demonstrated stronger significant associations with their PA levels compared to parent-reported measures. Congruence in reporting expectation, facilitation, monitoring, non-directive support, and autonomy support was positively associated with adolescent PA, while incongruence in these practices showed inverse associations. In addition, adolescents’ gender-specific analyses demonstrated different informant effects on disengagement, monitoring, and non-directive support.

Conclusion

Parent-adolescent (in)congruences on positive PAPP rather than negative PAPP showed significant relationships with adolescents’ PA levels, highlighting the importance of aligning parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions on positive PAPP to promote adolescent PA. Moreover, adolescent girls appear to be more sensitive to PAPP involving parents’ presence than boys.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20709-0.

Keywords: Adolescents, Physical activity, Parenting practices, Response surface analysis, Informant discrepancy

Introduction

Promoting physical activity (PA) among children and adolescents is widely recognized as a public health priority, given its significant benefits for both physical fitness and mental health [1, 2]. However, recent global surveillance data indicate that 81% of students aged 11–17 did not meet the recommended minimum of one hour of moderate to vigorous PA per day [3]. Factors that influence youth PA operate across multiple ecological levels [2]. At the interpersonal level, parents serve as crucial change agents by providing enabling conditions and fostering autonomous motivations for their children’s PA engagement [4, 5]. Specifically, parents influence their children’s PA through words and actions, known as PA parenting practices (PAPP). These childrearing approaches are considered one of the most significant determinants of PA outcomes [5–8].

Systematic reviews have confirmed significant correlations between PAPP and youth PA outcomes [9, 10]. But a meta-analysis of 115 studies demonstrates that the correlations are generally weak and the across-study heterogeneity is large [11]. Experts attribute the inconsistencies to the discordance in the conceptualization and operationalization of PAPP. To address this issue, scholars have proposed a unified conceptual framework to standardize the operationalization of measures, which categorizes PAPP into three parenting domains [8]. The control domain reflects Baumrind’s definition of control with an emphasis on practices that are inconsistent with child interests and values [12, 13]. The structure domain focuses on parenting practices that shape child’s physical and social environment to promote physical activity [8]. The autonomy support domain aligns with Baumrind’s definition of responsiveness that parents promote child PA participation by fostering individuality and self-assertion [8, 12]. This conceptual framework supports the development of an item bank for measuring nine types of PAPP [14].

Another important issue infringes PAPP research is that most PAPP studies rely on parent-reported data. Informant discrepancy is a well-documented phenomenon in parenting research [15–18]. A meta-analysis encompassing 313 studies noted that the degree of concordance between parent-adolescent dyads was markedly low, with a significant but weak correlation coefficient (r) of 0.28 [18]. Although only a few studies have examined the discrepancy in parent-adolescent perceptions of PAPP, all have reported high levels of discrepancies [16, 19–23]. According to Family Systems Theory, effective family functioning can contribute to adolescent health benefits [24, 25]. Informant discrepancy in parent-adolescent reported parenting practice can serve as an indicator for family functioning [26]. Congruence between parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions on supportive parenting indicates reciprocal understanding and cohesive familial environment [27]. While incongruent perceptions often reflect alienated and conflicted relationship and suboptimal communication between parents and their children [28, 29]. A previous study found that the informant discrepancy in paternal expectation for PA was inversely correlated with adolescents’ moderate to vigorous PA [23], indicating that informant discrepancy in parent-adolescent reports on PAPP may affect adolescents’ PA. Thus, the potential influence of perceptional discrepancy on PAPP warrants further examination. In addition, several studies found that adolescents’ reports are more strongly associated with their PA [16, 19–21]. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating both parents’ and their children’s perspectives to address perceptual discordances and fully capture the diverse impacts of PAPP on adolescents’ PA levels.

Careful consideration of methodology is essential to comprehensively investigate the informant discrepancy in parent-adolescent reports on different PAPP. The available study examined the informant discrepancy effect of PAPP using the different score approach [23]. This method has multiple limitations. It confounds the separate impacts of each predictor, making it impossible to isolate their unique contributions [30–32]. When a significant correlation exists between the difference score and the outcome variable, this method cannot distinguish whether the effect comes from the difference score itself or the individual predictors that comprise it [31]. What’s more, this method treats high and low levels of congruence as equivalent, though minor discrepancies at different levels may carry varying weights, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions about the congruence effect [33, 34]. It also assumes that the two predictors correlate with the outcome variable in opposite directions, whereas evidence suggests that informants’ reports generally exhibit consistent correlations with the outcome [35, 36]. Thus, the different score approach may not accurately reflect the effect of informant discrepancy.

Polynomial regression analysis combined with response surface analysis (RSA) can overcome the limitations of the difference score method [30, 32, 34, 37]. This method can elucidate the fit pattern of paired observations and demonstrate how combinations of two variables produce optimal effects on an outcome variable [34]. Scholars have applied this approach to investigate how informant discrepancy in parenting behaviors affect adolescents’ psychological and behavioral outcomes [37–41]. Their findings indicate that both consistency and discrepancy in parent-adolescent reports can both influence adolescents’ psychological and behavioral outcomes [37–41]. However, this methodology has not yet been utilized to explore the impact of informant discrepancy in PAPP on adolescent PA.

Despite methodological limitations, existing studies on PAPP informant discrepancy also involve very limited population samples. Informant discrepancy in reports of parenting practices can vary across different racial and national context [40]. Given the limited social and physical resources for Chinese adolescent PA, the critical role of Chinese parents in promoting adolescent PA becomes even more pronounced [42–44]. Previous research has found that parental support and modeling for PA are associated with Chinese adolescents’ PA [11, 45, 46]. However, these studies have only assessed a few types of PAPP, and have solely utilized parent-reported PAPP scores, overlooking the potential impact of discrepancy in parent-adolescent reports. Therefore, the current study aims to investigate parent-adolescent perceptual (in)congruences across nine types of PAPP and examine their associations with adolescents’ PA levels. We employed polynomial regression analysis combined with Response Surface Analysis (RSA) to explore fit patterns for a more nuanced understanding [31, 32, 34].

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from three public secondary schools in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. These schools were selected based on socioeconomic status and willingness to cooperate with assistance from the local Center of Disease Prevention and Control and Education Bureau. One school had over 80% of its students from migrant families, while the second school had about 50% and the third schools had less than 20% of students from migrant families. As migrant families were from less developed rural or suburban areas for better employment opportunities, these three schools can represent three tiers of socioeconomic levels in Suzhou. Students and parents from the three schools were invited via oral and written announcements. Consent forms were distributed in classes at least one day prior to the survey. Participants were screened based on the following inclusion criteria: adolescents were aged between 12 and 15 years with no health conditions restricting daily physical activities, and parents were mothers or fathers who lived with the student, and both student and one of the parents signed the consent form. In total, 590 parents and 725 students provided valid survey data. Among them, 373 parent-adolescent dyads were identified based on family ID and included in the present study. The sample of adolescents comprised 200 girls (53.6%) and 173 boys (46.4%), and their mean age was 13.5 ± 0.7 years. Approximately one-third of the adolescents (31.9%) reported being the only child in their families. The majority of parents participating in the survey were mothers (77.8%), and nearly half had a bachelor’s degree or higher (48.5%). More than half of the families reported a monthly income of 6,001 yuan (equivalent to 825 USD) or above.

Procedure

This survey study applied a cross-sectional design. Data was collected between April and June 2023. Research assistants introduced the survey to students in classroom settings, and the students filled out paper questionnaires by themselves with additional assistance if needed. After adolescents completed the survey, an online survey was provided to the Headteachers to send to the parent group. Parents self-administrated the survey using their own electronic devices. To mitigate the potential influence of social desirability bias in self-reported surveys, the instruction page of the questionnaires stated that “Please read the questions and options carefully before selecting the answer that most closely match your situation. There are no right or wrong answers to your responses. We will process your questionnaire anonymously, and the information you provide will be strictly confidential and will not be disclosed to others.” In the student survey, this statement also announced verbally in class. Data entry of the study survey was done using EpiData3.1 adhering to a double-entry verification procedure to guarantee the accuracy and integrity of the data. The research procedure was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Suzhou Medical School of Soochow University and adhered strictly to the principles mentioned in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Adolescent physical activity parenting practice

Drawing upon the international PAPP framework and item bank as a reference [8, 14], the CYPAPP questionnaire was developed through a rigorous process involving translation, adaptation, expert consultation, and cognitive and psychometric tests, resulting in a 48-item questionnaire exhibiting adequate construct validity, internal consistency, predictive validity, and test-retest reliability. For the full sets of measurement items and scoring scheme, please refer to Appendix A and B.

The questionnaire has two versions concurrently solicited perspectives from both parents and adolescents regarding their experiences with nine types of PAPP. The definition and exemplar measurement items are as follows. Punishment refers to parents punishing or threating to punish if their children refuse to do PA, measured using 4 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.87/0.90, e.g. “I/My parents threaten to punish child/me, such as adding homework or housework, if my child/I refuse(s) to take part in physical activity or sports.”) Pressuring refers to parents forcefully demanding their children to participate in PA, measured using 7 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.82/0.79, e.g. “To help my child/me improve at sports or physical activity, I/my parents have to push my child/me hard.”) Restriction refers to parents restricting adolescent PA for various concerns, assessed using 4 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.78/0.72, e.g. “I/My parents restrict my child’s/my physical activity due to safety concerns.”) Disengagement means that parents disengage in adolescent PA by being inattentive, refusing or postponing doing PA with their children, evaluated with 3 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.61/0.68, e.g. “I/My parents have delayed or canceled plans to engage in physical activities with my child/me due to some reasons, such as fatigue, time conflicts, poor weather, etc.”) Expectation refers to the standards that parents set for their children regarding when, how much, and how well they do with PA, measured using 6 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.76/0.76, e.g. “I/My parents expect my child/me to get excellent physical score or performance.”) Facilitation is interpreted as parents facilitating adolescent PA by ensuring the availability of equipment and facilities, evaluated using 3 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.62/0.70, e.g. “I/My parents will actively purchase sports related products in order to promote child’s/my physical activity.”) Monitoring is defined as parents monitoring and supervising adolescent PA, measured using 4 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.80/0.80, e.g. “I/My parents supervise child’s/my physical activity from the side to ensure safety.”) Non-directive support refers to parents supporting adolescent PA by co-participation, modeling, and planning, measured using 6 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.88/0.84, e.g. “I/My parents engage in physical activities in front of my child/me.”) Autonomy support means that parents support adolescent autonomy in PA by providing information and emotional support and encouraging decision-making, evaluated using 11 items (Cronbach’s α of parent/adolescent measures: 0.88/0.90, e.g. “I/My parents listen attentively when child/I talk about physical activities.”) Responses to all PAPP items were measured using 5-point Likert scales.

Adolescent physical activity level and demographic information

Adolescents’ PA levels were measured using the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents [47]. The Chinese version of this questionnaire has demonstrated acceptable validity against an accelerometer [48]. Adolescents responded to 3 items regarding their PA levels at school, and 3 items regarding their PA levels out of school, and 1 item about their overall PA levels. The total scores of all questions reflected the adolescents’ overall PA levels. Please find the 7 items in Appendix C.

The essential data comprises the adolescent’s grade, gender, age, parental educational level, family monthly income, relationship with the adolescent, and the child’s status within the family. The delineation of monthly family income categories was derived by integrating relevant literature on the socioeconomic status of Chinese households [49, 50], analyzing the income distribution of urban residents in Suzhou City in 2020 [51], and considering the preliminary research results from the initial stages of this study [22]. Thus, four monthly family income level options were determined: ≤ 6000 yuan, 6001–10,000 yuan, 10,001–15,000 yuan, and > 15,001 yuan. Yuan is the currency of mainland China.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were performed through SAS 9.4. Associations between congruence scores and adolescent PA were examined using multiple linear regression models after adjusting for parents’ gender, education, adolescents’ gender, and single-child status. These covariates were also adjusted in subsequent analyses. Polynomial regression analysis and Response Surface Analysis (RSA) of the total sample and adolescents’ gender-specified sample were applied for further investigation of the discrepancy effect using the RSA package [34] in R 4.4.0 [52]. Following the steps outlined by Nestler [31], adolescent- and parent-reported data on adolescent PA were first centered around their respective mean values. Then, multiple polynomial models for each PAPP were performed to overcome the potential overfitting risk of full polynomial models [34]. The optimal model was selected based on the assessment of the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc), comparative fit index (CFI), and variance explained (R2adj). Since the magnitude of AICc depends on arbitrary constants in the calculation, a ΔAICc < 2 and CFI ≥ 0.95 are perceived as a relatively good fit [53]. If multiple models fitted the criteria, the model with higher R2adj was preferred [54, 55], and the model selection of the same PAPP construct for gender-specified samples also considered model consistency across samples.

The polynomial regression yielded five coefficients demonstrating the slope. The coefficient b1 signifies the linear association between parent-reported PAPP and adolescent PA. The coefficient b2 represents the linear association between adolescent-reported PAPP and adolescent PA. The coefficient b3 indicates the association between the squared terms of parents-reported PAPP and the adolescent PA. The coefficient b4 represents the association between adolescent- and parent-reported PAPP interaction terms and adolescent PA. The coefficient b5 represents the association between the squared terms of adolescent-reported PAPP and the adolescent PA. Response surface plots are practical solutions to visualize the hard-to-interpret polynomial regression results. The main features of RSA are the line of congruence (LOC), the line of incongruence (LOIC), and the first principal axis (FPA) of the surface. Coefficient a1 equals b1 + b2, indicating the slope of LOC at the point of (0, 0). Coefficient a2 equals b3 + b4 + b5, indicating whether the LOC has a linear shape (a2 = 0) or a curvilinear shape (a2 ≠ 0). Coefficient a3 equals b1 - b2, indicating the slope of LOIC at the point of (0, 0). Coefficient a4 equals b3 - b4 + b5, indicating whether the LOIC has a linear shape (a4 = 0) or a curvilinear shape (a4 ≠ 0). Coefficient a5 equals b3 – b5, indicating the equality of the FPA and the LOC (a5 = 0). In models allowing shifted and rotated ridge, new parameters of a4’, C and S are added to the model to represent the misfit effect, lateral shifting and rotation of the surface respectively. Covariates adjusted in the polynomial models included parent’s gender and education, adolescents’ gender and single child status.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of parent- and adolescent-reported PAPP scores, as well as their associations with adolescents’ PA levels. Both sets of data demonstrate relatively lower scores in punishment and restriction, and higher scores in expectation and non-directive supports. Parent-reported facilitation and autonomy support and adolescent-reported expectation, facilitation, monitoring, non-directive support, and autonomy support were significantly positively associated with adolescent PA (β = 0.14∼0.35). Adolescent-reported disengagement was inversely associated with adolescent PA (β = -0.13).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of parenting practices and their associations with adolescents’ physical activity levels

| Parenting practices | Parent reported | Adolescent reported | Difference score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | β | p | mean | SD | β | p | mean | SD | β | p | |

| Punishment | 1.70 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 1.40 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.91 |

| Pressuring | 2.39 | 0.66 | -0.02 | 0.64 | 2.22 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 0.85 | -0.01 | 0.72 |

| Restriction | 1.71 | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.68 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Disengagement | 2.30 | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 2.15 | 0.77 | -0.13 | < 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Expectation | 4.16 | 0.54 | -0.01 | 0.86 | 3.74 | 0.72 | 0.35 | < 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.81 | -0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Facilitation | 2.29 | 0.79 | 0.14 | < 0.01 | 2.46 | 0.90 | 0.29 | < 0.001 | -0.17 | 0.97 | -0.16 | < 0.001 |

| Monitoring | 3.41 | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 3.20 | 0.92 | 0.14 | < 0.001 | 0.21 | 1.01 | -0.09 | 0.01 |

| Non-directive support | 3.90 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 3.73 | 0.82 | 0.24 | < 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.87 | -0.19 | < 0.001 |

| Autonomy support | 3.41 | 0.59 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 3.16 | 0.84 | 0.30 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.86 | -0.21 | < 0.001 |

Difference scores were calculated from parent-reported scores subtracting adolescent-reported scores. Linear regression models were adjusted for parent’s gender and education, and adolescents’ gender and single child status

Parent-adolescent (in)congruences

Table 2 presents the correlational relationships and levels of congruence between parent- and adolescent-reported PAPP scores. Congruence levels were assessed by a cutpoint of |Δz| > 0.5, which ranged from 34 to 46%, indicating that parent-adolescent discrepancies exist in most parent-adolescent dyads. The correlations revealed weak agreement as well, with coefficients ranging from 0.11 to 0.34. Difference scores, calculated by subtracting adolescent scores from parent scores, were significantly greater than zero for all PAPP except for restriction and facilitation (Table 1), suggesting that parents generally reported higher PAPP scores. Linear regression analysis showed that the higher difference scores in positive parenting behaviors, namely expectation, facilitation, monitoring, non-directive support, and autonomy support, were associated with lower levels of adolescent PA (β = -0.28∼-0.09).

Table 2.

Correlational results and level of congruence

| Adolescent reported | Parent reported | %P > A | %congruent | %P < A | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| 1 Punishment | 0.13* | 0.15** | -0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | -0.05 | 0.05 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 43% | 42% | 14% |

| 2 Pressuring | 0.18*** | 0.25*** | 0.06 | 0.04 | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.03 | -0.07 | -0.04 | 39% | 36% | 25% |

| 3 Restriction | 0.00 | -0.04 | 0.27*** | 0.06 | -0.10 | -0.09 | -0.05 | -0.09 | -0.13* | 31% | 42% | 27% |

| 4 Disengagement | -0.01 | -0.04 | 0.02 | 0.11* | -0.09 | -0.02 | -0.08 | -0.12* | -0.14** | 35% | 45% | 20% |

| 5 Expectation | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | -0.01 | 0.21*** | 0.27*** | 0.16** | 0.15** | 0.21*** | 48% | 40% | 13% |

| 6 Facilitation | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.19*** | 0.34*** | 0.15** | 0.20*** | 0.28*** | 25% | 38% | 37% |

| 7 Monitoring | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | -0.02 | 0.14** | 0.21*** | 0.22*** | 0.13* | 0.23*** | 42% | 34% | 25% |

| 8 Non-directive support | -0.01 | -0.08 | 0.03 | -0.12* | 0.14** | 0.19*** | 0.14** | 0.26*** | 0.31*** | 32% | 46% | 21% |

| 9 Autonomy support | 0.00 | -0.07 | 0.07 | -0.07 | 0.18*** | 0.21*** | 0.15*** | 0.22*** | 0.32*** | 42% | 36% | 22% |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. A cutpoint of |Δz| > 0.5 is used to determine numerical congruence. P > A indicates that parent-reported scores are higher than adolescent-reported scores, and vice versa

(In)Congruence effects from RSA models

RSA models were selected based on AICc, CFI, and variance explained. For detailed information on model comparisons, please refer to Supplementary Table 2. The selection of null models indicates that there were no congruence effects of punishment, pressuring, and restriction on adolescent PA.

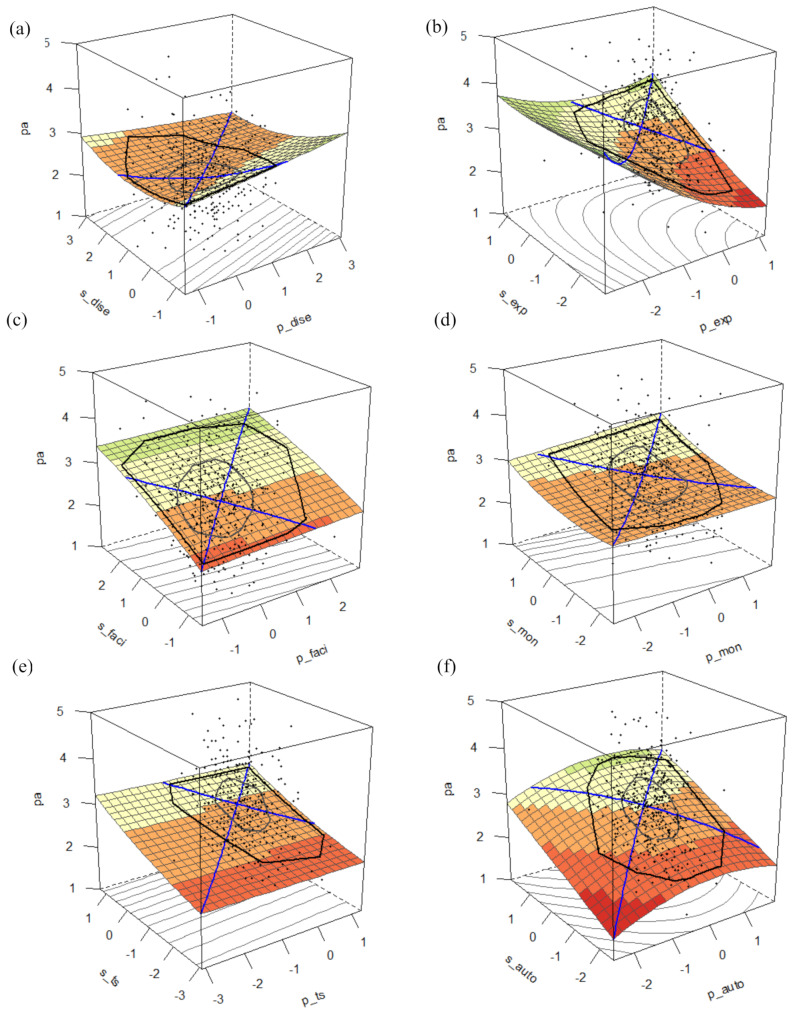

As shown in Table 3, the polynomial regression analyses found that adolescent PA was only significantly associated with adolescent-reported disengagement, expectation, facilitation, monitoring, non-directive support, and autonomy support (b2 = -0.16 to 0.37, all p < 0.001). The RSA models of these PAPP, excluding disengagement, yielded significantly linear positive effects of LOC (a1 = 0.18 to 0.33, all p < 0.001). The RSA model of these PAPP also yielded significantly linear negative effects of LOIC (a3 = -0.42 to -0.12, all p < 0.05), while the LOIC effect of disengagement was linearly positive (a3 = 0.21, p < 0.01). The visual presentations of these RSA models are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Model estimates of polynomial regression analyses and response surface analyses among 373 dyads

| Parenting practices | Model | Polynomial regression slope | RSA coefficient | R 2 adj | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | b5 | a1 | a2 | a3 | a4 | a5 | C | S | a4’ | |||

| Disengagement | SRSQD | 0.05 | -0.16** | 0.01 | -0.04 | 0.06 | -0.10 | 0.03 | 0.21** | 0.12 | -0.06 | 1.23* | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.04 |

| Expectation | SRRR | -0.05 | 0.37*** | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.31*** | 0.25 | -0.42*** | 0.221 | 0.05 | -2.16 | -1.53 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Facilitation | SRSQD | 0.03 | 0.30*** | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.02 | 0.33*** | -0.03 | -0.27*** | -0.02 | 0.02 | 6.59 | -0.10 | -0.09 | 0.17 |

| Monitoring | SRSQD | 0.03 | 0.15*** | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.18*** | 0.06 | -0.12* | 0.03 | -0.04 | -1.70 | -0.20 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| Non-directive support | SRSQD | -0.02 | 0.26*** | 0.00 | -0.00 | 0.02 | 0.24*** | 0.02 | -0.28*** | 0.02 | -0.02 | -6.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Autonomy support | SRR | -0.03 | 0.29*** | -0.01 | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.31*** | 0.00 | -0.26*** | -0.05 | 0.00 | 5.81 | - | - | 0.16 |

Note: SRR shifted rising ridge model; SRRR rotated and shifted rising ridge model; SRSQD rotated squared difference model. The b1 to b5 are the coefficients in the polynomial regression equation of the corresponding model. The a1 coefficient (b1 + b2) represents the slope of the line of congruence (LOC); the a2 coefficient (b3 + b4 + b5) represents the linear or curvilinear shape of the LOC; the a3 coefficient (b1 - b2) represents the slope of the line of incongruence (LOIC); the a4 coefficient (b3 – b4 + b5) represents the linear or curvilinear shape of the LOIC; the a5 coefficient (b3– b5) represents whether the first principal axis (FPA) and LOC are equal. In the SRSQD model, the C coefficient (-1/2(b2/b5)) is a shifting constant applied to the X predictor. the S coefficient (-b4/(2b5)) is scaling factor for X. the a4’ (b3/S2 − b4/S + b5) coefficient is the relevant index that tests for the presence of a misfit effect. Covariates adjusted for parent’s gender and education, adolescents’ gender and single child status. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Fig. 1.

Response surface plots of parent- and adolescent-reported physical activity parenting practices in explaining adolescent physical activity (p.a.). (a) plot of parent- and adolescent-reported disengagement (p_dise, s_dise); (b) plot of parent- and adolescent-reported expectation (p_exp, s_exp); (c) plot of parent- and adolescent-reported facilitation (p_faci, s_faci); (d) plot of parent- and adolescent-reported monitoring (p_mon, s_mon); (e) plot of parent- and adolescent-reported non-directive support (p_ts, s_ts); (f) plot of parent- and adolescent-reported autonomy support (p_auto, s_auto)

Adolescents’ gender-specific analyses yielded similar results regarding the informant effects, with exceptions for disengagement, monitoring, and non-directive support. Among parent-daughter dyads, adolescent PA was associated with parent- and adolescent-reported disengagement, as well as the level of parent-adolescent incongruence (b1 = 0.12, b2 = -0.12, a3 = 0.23, all p < 0.01). In addition, the LOC of monitoring and non-directive support exhibited significantly curvilinear positive effects on girls’ PA (a1 = 0.12, a2 = -0.10 and a1 = 0.15, a2 = -0.17, respectively). In contrast, these effects were insignificant among parent-son dyads. Detailed model estimates of the gender-specific analyses are in Supplementary Tables 3, and visual comparisons of the informant effects by adolescents’ gender are in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Discussion

A large volume of research has focused on PAPP [9, 11], but their weak and inconsistent findings regarding the influence of PAPP on youth PA are somewhat discouraging [11]. Despite that, several studies have observed discrepancies in parent- and child-reported PAPP [17, 19, 20], existing studies mainly rely on parents’ reports of their own PAPP [56] and neglect the effect of discrepancies in parent- and adolescent-reported PAPP. To address this gap, the present study assessed nine types of PAPP among parent-adolescent dyads and employed polynomial regression combined with RSA to comprehensively examine how perception congruences and incongruences on these nine PAPP would influence adolescents’ PA levels, respectively.

When it comes to parent-adolescent discrepancies in reporting PAPP, the agreement between adolescents and parents on reporting the nine types of PAPP was generally low, with the agreement percentages ranging from 34 to 46%. Our findings align with previous studies on parenting practices, which reported an average agreement of 44.1% between adolescents and parents [41]. In addition, the weak correlations between parent- and adolescent-reported PAPP (r = 0.11 ∼ 0.34) were similar to the pooled correlational effect size (r = 0.28) from a meta-analysis of 313 studies that examined relationships between parent- and adolescent-reported five parenting attributes (i.e., warmth, behavioral control, psychological control, relationship quality, family functioning) [18]. The difference scores revealed that parents reported higher levels of positive PAPP, such as expectation, monitoring, non-directive support, and autonomy support, compared to adolescents. A plausible explanation for this discrepancy is that parents may be influenced by social desirability, leading them to over-report positive behaviors [16, 57]. However, parents reported lower scores in facilitation than adolescents, likely because facilitation involves purchasing sports products and ensuring access to sports facilities. Adolescents may focus more on their frequency of using these products and services, which exceeds the frequency of their parents’ acquisition. Our research also found that, compared to adolescents, parents reported higher levels of punishment, pressuring, restriction, and disengagement. This contrasts with previous study showing that adolescents typically report higher levels of negative parenting practices [58]. One possible explanation for these differing results is that adolescents may have become accustomed to parental pressure and punishment, perceiving them as being done “for their own good” [59–61]. Furthermore, middle-aged parents of adolescents, who often face life stressors such as demanding work schedules and financial constraints [40], may not be able to proactively participate in their children’s PA. Once adolescents get used to these situations, they may pay less attention to the frequency of parental controlling behaviors and disengagement.

As for associations between PAPP and adolescent PA, results from multiple linear regression analysis showed that adolescent PA was significantly associated with all five positive PAPP reported by the adolescent but only with two parent-reported positive PAPP (facilitation and autonomy support). The polynomial regression analysis further revealed that adolescent PA was significantly associated only with adolescent-reported positive PAPP. Consistent with previous studies, adolescent-reported PAPP demonstrates stronger associations with their PA levels [20, 21], suggesting that adolescents’ perceptions of PAPP are more crucial than parents’ self-reports. Adolescent-reported PAPP also reflect adolescents’ endorsement of these practices, which influences their willingness to comply [13]. However, it is noteworthy that the adolescent self-reported their PA levels, which may introduce potential biases leading to higher associations with other adolescent-reported variables. Thus, the findings need to be further validated using objectively measured adolescent PA.

Multiple linear regression and polynomial regression analysis found no significant association between adolescent PA and parent- or adolescent-reported negative PAPP (punishment, pressuring, restriction), except for disengagement. Consistent with findings from previous studies [70], negative parenting practices (i.e., punishment and discouragement) were not significantly associated with adolescent PA. The potential reason for the insignificant relationship could be that the adolescent sample was relatively young, and they might perceive negative PAPP as legitimate. When adolescents get older, the legitimacy of negative PAPP tends to decline and the issue of negative PAPP may become more pronounced [62]. Hence, subsequent studies need to incorporate adolescents of other age groups for comparison and validate the long-term impact of negative PAPP on adolescent PA.

The RSA findings provided a more direct and nuanced depiction of the (in)congruence effect on adolescent PA. Regarding the three negative PAPP (punishment, pressuring, and restriction), the effect of informant discrepancy was not significant. The null findings may be attributed to confounding factors related to the study design. First, adolescents with controlling parents might over-report their PA levels out of fear of blame [63]. They may also deliberately under-report negative PAPP to avoid feelings of shame. Moreover, parental coercive behaviors may temporarily increase adolescent PA levels [64], which conflicts with the potential scenario where parents tend to exhibit controlling behaviors due to their adolescents’ undesirable PA levels. Given the complexity of these confounding factors, the effects of negative PAPP and related effects of informant discrepancy should be examined qualitatively or longitudinally in future studies.

Higher levels of congruence between parent and adolescent reports of expectation, facilitation, encouragement, non-directive support, and autonomy support were associated with increased adolescent PA, while greater incongruence was associated with lower adolescent PA. One possible explanation is that high levels of congruence indicate a favorable parenting atmosphere, enabling adolescents to perceive parental support and subsequently improve their PA levels [21, 65]. Conversely, greater incongruence in reporting supportive PAPP may reflect poor parent-adolescent communication and relationship quality [18, 65]. In such cases, ineffective communication can lead to misunderstanding, reducing adolescents’ perception of parental support and ultimately resulting in lower PA levels.

The gender-specific models revealed that the informant discrepancy effects of disengagement, monitoring, and non-directive support were more pronounced among girls than boys. These three types of PAPP shared a common feature of parental presence in adolescents’ PA participation. Our previous focus group interviews found that more girls favored co-participation with their parents in physical exercises compared to boys [22]. There are also survey findings showing that parental support had greater influence on Chinese female high school students’ PA levels, while boys were more influenced by their peers [66]. Our findings not only showed that both girls’ and boys’ PA levels were affected by the informant discrepancy effects of multiple PAPP but also highlighted that girls may have a stronger desire for parental PA companionship. Their perception discrepancies on the levels of parental involvement may reflect suboptimal support from parental engagement.

Implications

This study has practical implications for parents and public health professionals in their efforts to promote youth PA. Our findings indicate that discrepancies exist between parents and adolescents in reports of PAPP and adolescent-reported PAPP having a more significant influence on their PA levels. Therefore, it is essential to investigate PAPP from adolescents’ perspectives. The effects of (in)congruence may be linked with the quality of parent-adolescent relationships and the overall family atmosphere, so family-based PA interventions need to raise parents’ awareness of their application of positive PAPP and improve parents’ communication skills with adolescents to foster high-quality parent-adolescent relationships. For instance, encouraging parents to regularly communicate with their adolescents to understand their perceptions of PAPP and explore strategies to foster a positive perception of positive PAPP can be beneficial [40, 67].

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The current study holds several strengths compared with other studies on the same topic. We developed PAPP measurement specifically tailored to Chinese parenting, encompassing nine distinct types of PAPP. This approach enabled a comprehensive and systematic assessment of PAPP. In addition, our study addressed the limitations of difference scores by applying polynomial regression analysis in conjunction with RSA, which allowed for the concurrent assessment and visualization of the relationship between (in)congruence in reported PAPP and adolescent PA.

However, this study also has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. The relatively low representation of fathers in our sample limited our ability to analyze the potential differences in parenting practices between mothers and fathers Additionally, adolescent PA was self-reported rather than being objectively measured, making it susceptible to recall bias. Moreover, the cross-sectional design prevented us from making any causal inferences. Future studies should adopt qualitative or longitudinal designs to better explore the complex interplay between parenting practices and adolescent PA. Additional attention should also be given to addressing dyadic measurement invariance [68]. For example, the latent congruence model allows for examining dyadic scores while modeling dyadic similarity and accuracy at a latent level [69].

Conclusion

This multi-informant study, utilizing polynomial regression and RSA analysis, provided a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between parent- and adolescent-reported PAPP and adolescent PA. The findings reveal a notable discrepancy in perceptions of PAPP between parents and adolescents, with adolescent-reported PAPP being more strongly associated with their PA levels. Specifically, higher levels of congruence between parents and adolescents on PAPP corresponded with higher adolescent PA, while greater incongruence, particularly when adolescents reported lower levels of supportive PAPP, was associated with lower adolescent PA. These results highlight the importance of considering adolescents’ perspectives on parenting behaviors and the significant impact of parent-adolescent (in)congruence on adolescent PA. To effectively enhance adolescent PA, interventions should focus on improving PAPP by aligning parents’ actions with adolescents’ perceptions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the experts who contributed to the content validity assessment and all the parents and adolescents who participated in this study. The authors would like to extend their thanks to the Suzhou Municipal Education Bureau and Center for Disease Control and Prevention as well as the school nurses and staff from the participating schools for their support in participant recruitment and coordination.

Abbreviations

- PA

Physical activity

- PAPP

Physical activity parenting practices

- RSA

Response surface analysis

Author contributions

YC analyzed the data and drafted the majority of the manuscript; SSP and YXL wrote the specific chapters; RHC performed data collection and data cleaning; YJZ (the corresponding author) designed the study, supervised all aspects of its implementation, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82204068].

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from Youjie Zhang (ujzhang@suda.edu.cn) on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Suzhou Medical College of Soochow University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent by signing a consent form before taking the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yu Chen, Shasha Pan and Yixi Lin contributed equally to this work and should be regarded as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Sluijs EMF, Ekelund U, Crochemore-Silva I, Guthold R, Ha A, Lubans D, et al. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet Lond Engl. 2021;398:429–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwardson CL, Gorely T. Parental influences on different types and intensities of physical activity in youth: a systematic review. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11:522–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jago R, Davison KK, Brockman R, Page AS, Thompson JL, Fox KR. Parenting styles, parenting practices, and physical activity in 10- to 11-year olds. Prev Med. 2011;52:44–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as Context: an integrative model. In: Interpersonal Development. Routledge; 2007.

- 7.Gustafson SL, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Med. 2006;36:79–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mâsse LC, O’Connor TM, Tu AW, Hughes SO, Beauchamp MR, Baranowski T, et al. Conceptualizing physical activity parenting practices using expert informed concept mapping analysis. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchens A, Lee RE. Parenting practices and children’s physical activity: an integrative review. J Sch Nurs. 2018;34:68–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu H, Wen LM, Rissel C. Associations of parental influences with physical activity and screen time among Young children: a systematic review. J Obes. 2015;2015:546925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao CA, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates in child and adolescent physical activity: a meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison KK, Mâsse LC, Timperio A, Frenn MD, Saunders J, Mendoza JA, et al. Physical activity parenting measurement and research: challenges, explanations, and solutions. Child Obes Print. 2013;9(Suppl Suppl 1):S103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mâsse LC, O’Connor TM, Lin Y, Carbert NS, Hughes SO, Baranowski T, et al. The physical activity parenting practices (PAPP) item Bank: a psychometrically validated tool for improving the measurement of physical activity parenting practices of parents of 5–12-year-old children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korelitz KE, Garber J. Congruence of parents’ and children’s perceptions of parenting: a Meta-analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:1973–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebholz CE, Chinapaw MJ, van Stralen MM, Bere E, Bringolf B, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Agreement between parent and child report on parental practices regarding dietary, physical activity and sedentary behaviours: the ENERGY cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Baltaci A, Overcash F, Druziako S, Peralta A, Hurtado GA, et al. Latino adolescent-father discrepancies in reporting activity parenting practices and associations with adolescents’ physical activity and screen time. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou Y, Benner AD, Kim SY, Chen S, Spitz S, Shi Y, et al. Discordance in parents’ and adolescents’ reports of parenting: a meta-analysis and qualitative review. Am Psychol. 2020;75:329–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr-Anderson DJ, Robinson-O’Brien R, Haines J, Hannan P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parental report Versus Child Perception of familial support: which is more Associated with Child Physical Activity and Television Use? J Phys Act Health. 2010;7:364–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niermann CYN, Wagner P, Ziegeldorf A, Wulff H. Parents’ and children’s perception of self-efficacy and parental support are related to children’s physical activity: a cross-sectional study of parent–child dyads. J Fam Stud. 2022;28:986–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Hager ER, Magder LS, Arbaiza R, Wilkes S, Black MM. A dyadic analysis on source discrepancy and a Mediation Analysis via self-efficacy in the parental support and physical activity relationship among black girls. Child Obes. 2019;15:123–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Cao R, Li C, Shi Z, Sheng H, Xu Y. Experiences, perspectives, and barriers to Physical Activity Parenting practices for Chinese early adolescents. 2023. 10.1123/jpah.2022-0433 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhang Y, Reyes Peralta A, Arellano Roldan Brazys P, Hurtado GA, Larson N, Reicks M. Development of a survey to assess latino fathers’ parenting practices regarding Energy Balance–related behaviors of early adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47:123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keith DV. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Psychosomatics. 1980;21:439–43. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grevenstein D, Bluemke M, Schweitzer J, Aguilar-Raab C. Better family relationships––higher well-being: the connection between relationship quality and health related resources. Ment Health Prev. 2019;14:200160. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Los Reyes A, Ohannessian CM. Introduction to the Special Issue: discrepancies in adolescent-parent perceptions of the Family and Adolescent Adjustment. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:1957–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trang DT, Yates TM. (In)congruent parent–child reports of parental behaviors and later child outcomes. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29:1845–60. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurizi LK, Gershoff ET, Aber JL. Item-level discordance in parent and adolescent reports of parenting behavior and its implications for adolescents’ mental health and relationships with their parents. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:1035–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehrlich KB, Richards JM, Lejuez CW, Cassidy J. When parents and adolescents disagree about disagreeing: observed parent-adolescent communication predicts informant discrepancies about conflict. J Res Adolesc off J Soc Res Adolesc. 2016;26:380–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laird RD, De Los Reyes A. Testing informant discrepancies as predictors of early adolescent psychopathology: why difference scores cannot tell you what you want to know and how polynomial regression May. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nestler S, Humberg S, Schönbrodt FD. Response surface analysis with multilevel data: illustration for the case of congruence hypotheses. Psychol Methods. 2019;24:291–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanock LR, Baran BE, Gentry WA, Pattison SC, Heggestad ED. Polynomial regression with response surface analysis: a powerful Approach for Examining Moderation and Overcoming limitations of difference scores. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25:543–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards JR. Ten difference score myths. Organ Res Methods. 2001;4:265–87. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schönbrodt F. Testing fitting patterns with polynomial regression models. 2016.

- 35.De Los Reyes A, Ehrlich KB, Swan AJ, Luo TJ, Van Wie M, Pabón SC. An experimental test of whether informants can report about child and family behavior based on settings of behavioral expression. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22:177–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Los Reyes A, Salas S, Menzer MM, Daruwala SE. Criterion validity of interpreting scores from multi-informant statistical interactions as measures of informant discrepancies in psychological assessments of children and adolescents. Psychol Assess. 2013;25:509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Human LJ, Dirks MA, DeLongis A, Chen E. Congruence and incongruence in adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions of the family: using response surface analysis to Examine Links with adolescents’ Psychological Adjustment. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:2022–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu J, Zhou T. Parent-adolescent congruence and discrepancy in perceived parental emotion socialization to anger and sadness: using response surface analysis to examine the links with adolescent depressive symptoms. J Youth Adolesc. 2024;53:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo R, Chen F, Yuan C, Ma X, Zhang C. Parent–child discrepancies in perceived parental favoritism: associations with Children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in Chinese families. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49:60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Hou Y, Chen J, Yang X, Wang Y. The Association between discrepancies in parental emotional expressivity, adolescent loneliness and depression: a multi-informant study using response surface analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2024. 10.1007/s10964-024-02033-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Hawk ST. Adolescent-mother agreements and discrepancies in reports of Helicopter parenting: associations with Perceived Conflict and Support. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52:2480–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Jee S, Fu J, Wang B, Zhu L, Tu Y et al. Psychosocial characteristics, Perceived Neighborhood Environment, and physical activity among Chinese adolescents. 2021. 10.1123/jpah.2020-0397 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Wang L, Tang Y, Luo J. School and community physical activity characteristics and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among Chinese school-aged children: a multilevel path model analysis. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:416–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Ge X, Li H, Zhang E, Hu F, Cai Y et al. Physical activity maintenance and increase in Chinese children and adolescents: the role of intrinsic motivation and parental support. Front Public Health. 2023;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Liu Y, Zhang Y, Chen S, Zhang J, Guo Z, Chen P. Associations between parental support for physical activity and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among Chinese school children: a cross-sectional study. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:410–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Liu Q-M, Ren Y-J, Lv J, Li L-M. Family influences on physical activity and sedentary behaviours in Chinese junior high school students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kowalski K, Crocker P, Donen R, Honours B. The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) and Adolescents (PAQ-A) Manual. 2004.

- 48.Li X, Wang Y, Li X, Li D, Sun C, Xie M, et al. Reliability and validity of physical activity questionnaire for adolescents(PAQ-A) in Chinese Version. J Beijing Sport Univ. 2015;38:63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Yang C, Zhang Y, Hu X. Socioeconomic status and Prosocial Behavior: the mediating roles of Community Identity and Perceived Control. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang F, Jiang Y, Ming H, Yang C, Huang S. Family Socioeconomic Status and adolescents’ academic achievement: the moderating roles of subjective Social mobility and attention. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49:1821–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzhou Municipal Government. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Suzhou City in 2020. 2021. https://www.suzhou.gov.cn/szsrmzf/tjgb2021/202104/b737f95065e84ef3bbc44679ca6b604d.shtml. Accessed 20 Jul 2024.

- 52.Edwards JR, Parry ME, ON THE USE OF POLYNOMIAL, REGRESSION EQUATIONS AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO DIFFERENCE SCORES IN ORGANIZATIONAL RESEARCH. Acad Manage J. 1993;36:1577–613. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caby E, McQuarrie ADR, Tsai C-L. Regression and Time Series Model Selection. Technometrics. 2000;42:214. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guthery FS, Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and Multimodel Inference: a practical information-theoretic Approach. J Wildl Manag. 2003;67:655. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mâsse LC, O’Connor TM, Tu AW, Watts AW, Beauchamp MR, Hughes SO, et al. Are the physical activity parenting practices reported by US and Canadian parents captured in currently published instruments? J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:1070–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abar CC, Jackson KM, Colby SM, Barnett NP. Parent–child discrepancies in reports of parental monitoring and their relationship to adolescent alcohol-related behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:1688–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dimler LM, Natsuaki MN, Hastings PD, Zahn-Waxler C, Klimes-Dougan B. Parenting effects are in the Eye of the beholder: parent-adolescent differences in perceptions affects adolescent problem behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:1076–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the Cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994;65:1111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen B, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Van Petegem S, Beyers W. Where do the Cultural Differences in Dynamics of Controlling Parenting Lie? Adolescents as active agents in the perception of and coping with parental behavior. Psychol Belg. 2016;56:169–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen-Bouck L, Patterson MM, Chen J. Relations of Collectivism socialization goals and training beliefs to Chinese parenting. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2019;50:396–418. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smetana JG. Adolescents, families, and social development: how teens construct their worlds. Wiley; 2010.

- 63.Taber SM. The veridicality of children’s reports of parenting: a review of factors contributing to parent–child discrepancies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patrick H, Hennessy E, McSpadden K, Oh A. Parenting styles and practices in Children’s obesogenic behaviors: scientific gaps and future research directions. Child Obes. 2013;9:S–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tian L, Xin C, Zheng Y, Liu G. Parent–adolescent discrepancies in positive parenting and adolescent problem behaviors in Chinese families. Heliyon. 2024;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Qiu N, Gao X, Zhang X, Fu J, Wang Y, Li R. Associations between Psychosocial variables, availability of physical activity resources in Neighborhood Environment, and out-of-school physical activity among Chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pelton J, Forehand R. Discrepancy between mother and child perceptions of their relationship: I. consequences for adolescents considered within the context of parental divorce. J Fam Violence. 2000.

- 68.Tagliabue S, Zambelli M, Sorgente A, Sommer S, Hoellger C, Buhl HM, et al. Latent congruence model to Investigate Similarity and Accuracy in Family Members’ perception: the challenge of cross-national and cross-informant measurement (non)Invariance. Front Psychol. 2021;12:672383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheung GW. Introducing the latent congruence model for improving the assessment of similarity, agreement, and fit in organizational research. Organ Res Methods. 2009;12:6–33. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su DLY, Tang TCW, Chung JSK, Lee ASY, Capio CM, Chan DKC. Parental Influence on Child and Adolescent Physical Activity Level: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 15;19(24):16861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from Youjie Zhang (ujzhang@suda.edu.cn) on reasonable request.