Abstract

Abstract

Introduction

Teleworking is one of the most significant legacies of the pandemic. Great attention is now being paid to its effects on workers’ health. One of the arguments that emerged on this issue is that ‘working away from the office’ affects the time we spend with significant others. This calls into question all those processes that make relatives and colleagues important to our health, such as forms of mentoring and social support, but also conflicts, work interruptions or control over workers’ activities. So far, no study has evaluated the impact that teleworking has on these processes using data on personal networks. The Empty Office is the first study to use social network analysis to measure the impact that telework has on social relations and, in turn, workers’ health and well-being.

Methods and analysis

The project draws on a total sample of 4400 participants from Switzerland, the Netherlands, Spain and Germany (n=1100 per country). The choice of these countries is due to their specificity and diversity in socioeconomic features, which make them particularly interesting for studying teleworking from a comparative point of view. The research is conceived as a sequential mixed-method design. First, quantitative data collection will administer an online questionnaire to gather information on telework modalities, health and well-being markers, and data on personal networks collected by a name generator. A qualitative module, administered one year later, will consist of in-depth interviews with a subsample (n=32) of teleworkers selected for delving narratively into the mechanisms identified with the quantitative analyses.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has obtained 2 years of funding from the Swiss Network for International Study and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Geneva (CUREG-20230920-292-2). All participants will be asked to provide informed consent to participate in this study. The results will be shared with international organisations and disseminated in scientific journals and conferences. Fully anonymised data will be made available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) data-repository platform.

Keywords: Psychological Stress, Social Support, Social Interaction, Research Design, Quality of Life, Public health

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The mixed-method design allows the question to be approached through different research angles, taking advantage of quantitative, network and narrative data.

Through network analysis, the research explores the links between telework and well-being not only by looking at teleworkers as such, but also by constructing a large sample of their personal contacts.

This is an international study collecting data in Switzerland, Spain, Germany and the Netherlands.

One limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the quantitative data collection, which will allow causal mechanisms between telework and well-being to be explored through retrospective information alone.

Introduction

Today, there is a great deal of interest in how remote work is changing the labour market and what the consequences are for workers’ well-being1,2. Research on teleworking grew tremendously during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a fragmented picture of evidence that still needs to be strengthened. A variety of factors have emerged regarding the impact of teleworking on health, calling into question the characteristics of the work environment, the intensity of remote work, but also, and not least, workers’ preferences, which are often dictated by the stage of life they are in, for example, parenthood.3 From this set of different factors, multiple intertwined mechanisms have arisen, from which have emerged the benefits of more flexible schedules, less commuting and more time for self and family care.4 However, research has also shown that full-time teleworking can overload individuals cognitively, blur work–life boundaries and cause them to lose physical contact with others.3,6However, much of this evidence was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and has been affected by the contingencies and stressors of that period. Today, it seems necessary to lead telework research away from these exceptional circumstances.

With this goal in view, this project studies the effects of teleworking on well-being 2 years after the end of the pandemic, and it does so with a particular focus on social relationships. The rationale for having this focus is that, whether on the good or bad side of teleworking, experts and scholars place great emphasis on its effects on people’s social ties, especially those with family members and colleagues7 8; see also Ref 9 on ‘The Empty Office’. Yet, despite this, there is to date no research in this field using social network analysis (SNA), the main framework used to analyse the properties and structure of personal relationships.10 This is a very significant gap, as there are many advantages in applying SNA from both the theoretical and methodological points of view. SNA is an interdisciplinary scientific framework that offers a common grammar to scholars from a wide variety of sciences.11 Network research provides advanced data collection and analytical tools, as well as theories and concepts that are now well established. Conflicts, forms of support, control mechanisms and interruptions to work activities are mechanisms at the heart of teleworking studies that can best be understood through SNA concepts, including social capital, dormant ties, strong and weak ties, and reciprocity, to name but a few. From a methodological point of view, SNA allows the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data and enables the analysis of teleworking to be extended through a multiplicity of units of analysis: not only analysing the characteristics of teleworkers as such (ego), but also those of their personal contacts (alters) and of the relationships they establish with others (ego-alter).10

Hypothesis and research questions

Focusing on social relations, one of the most sensitive issues to emerge on teleworking concerns its intensity, that is, how many of the total work hours are spent remotely, and the consequent reduction of face-to-face interactions.12 A problematic aspect of a reduction of in-person encounters lies at the heart of social capital theory.13 Relations are indeed nurtured by social interaction, and without it they lose their functions, slowly becoming dormant.14 Dormancy is problematic because it deactivates the exchange of network resources, such as social support, which is a known protector of well-being.15 On one hand, therefore, a body of evidence suggests that, by reducing face-to-face interaction in favour of digital ones, teleworking may ‘turn off’ positive relations and social support, especially if this is done full time.16 17 On the other hand, the process of dormancy could also help reveal the flip side of social relationships, as some studies suggest: avoiding face-to-face encounters could be beneficial in avoiding interactions with difficult colleagues, thereby preventing forms of bullying or harassment.18 19 Considering these issues, this study tests two hypotheses linking the intensity of teleworking with professional relations: on one hand, the lesser ability to mobilise the social support of our positive relationships; and on the other hand, the benefits of keeping away ties that are sources of conflict, bullying and harassment. We therefore propose the following hypotheses:

H1. A high intensity of teleworking is associated with less bullying and harassment from collegues, with positive effects on well-being.

H2. A high intensity of teleworking is associated to lower levels of social support from colleagues, with negative effects on well-being.

In addition to the intensity of teleworking, it is also important to take into account ‘who’ performs teleworking. One interesting insight to emerge from the literature, still too little explored, is that bosses and managers can benefit more from being away from offices than most vulnerable workers.20 Those in authority may experience greater freedoms and have more time to spend with family and friends, who are often the main providers of bonding social capital, that is, support and care.21 On the other hand, less-skilled and lower-level workers could be more susceptible to forms of control on their time and schedules, as a few studies have suggested.22 23 Hence, in this study, we test two additional hypotheses that refer to the occupational status of people working remotely:

H3. Teleworkers with higher occupational status have higher levels of support and care from family networks and intimate ties, with positive effects on well-being.

H4. Teleworkers with lower occupational status report higher levels of social control from professional contacts, with negative effects on their well-being.

If ‘who’ teleworks and ‘how much’ are important questions, so is the ‘where’. The reason for this is that primarily, and from a relational point of view, the teleworking environment provides a context for social interactions.13 In the difficult time of lockdowns, for example, small and inadequate workspaces have been identified as susceptible to the emergence of conflict, especially among households with childcare duties.5 24 Teleworking spaces that are too small have also been associated with increased interruptions, as an indirect mechanism linked to lower job satisfaction.8 25 Two hypotheses also emerge that link teleworking with personal networks and in turn to well-being. The following hypotheses will be tested to quantify how the teleworking environment affects the presence of family conflicts and interruptions from coworkers:

H5. Appropriate spaces for teleworking are associated with fewer interruptions from contacts, with positive effects on well-being.

H6. Appropriate spaces for teleworking are associated with fewer family conflicts, with positive effects on well-being.

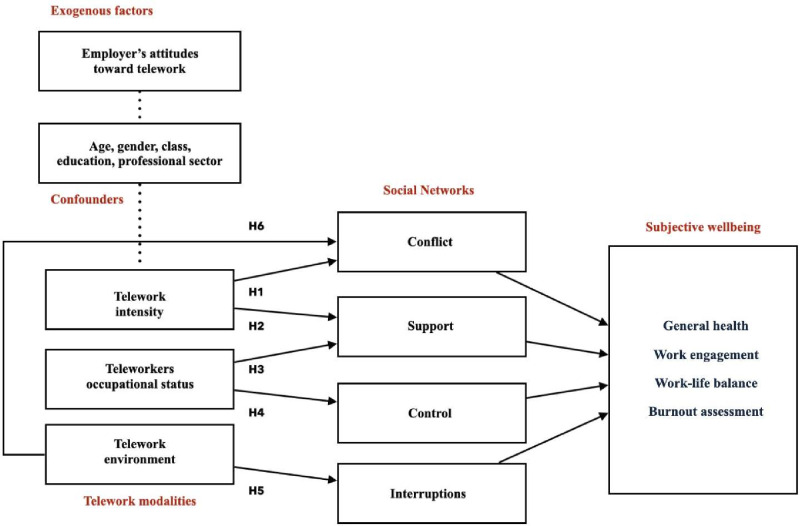

Considering these issues, in figure 1 we present an integrated model of analysis in which the links between teleworking, social networks and well-being emerge from these starting hypotheses. Support, conflict, control and interruptions are patterns of interaction that teleworkers assume, potentially, with each of their personal contacts. SNA offers a theoretical and methodological framework to verify these starting hypotheses by collecting personal network data.

Figure 1. Model of analysis and hypothesis.

Methods and analysis

Design

The project plans to collect data on teleworkers and their personal networks through a sequential mixed-method design consisting of two work packages:

WP1: quantitative survey including a data collection of personal networks (n≥4400) during summer 2024.

WP2: qualitative module of in-depth interviews using Network Canvas (n≥32) during spring 2025.

This design combines both the formal structural analyses of personal networks and the qualitative assessment of the meaning that teleworking has in people’s lives. In using a sequential mixed-method methodology,26 WP1 aims at collecting the socioeconomic characteristics of the teleworkers, data on the intensity of the work activity, the tasks to be performed, the occupational positions they hold, the employer’s attitude towards teleworking and the characteristics of the working environment. Validated measurements will be used to collect information on subjective well-being during this WP1 (full questionnaire available as online supplemental material 1). As highlighted in the analytical model, the quantitative analyses must identify the associations between dissimilar socioeconomic features, teleworking patterns and well-being. Following such analysis and the identification of socioeconomic profiles of interest, a subsample of teleworkers will be selected during WP2 for qualitative data collection. With this aim in view, a total of eight in-depth interviews per country (n=32) are planned using the Network Canvas software.27 The rationale of this qualitative module is to explore narratively, and in diverse socioeconomic profiles of interest, those mechanisms that are at the core of the analytical model: professional conflicts, social support mechanisms, processes of control over workers and work interruptions. Overall, the design applies a classical mixed methods logic in which a quantitative module tests the hypotheses and the qualitative module complements the results on the associations identified using narrative information. The use of Network Canvas enriches a classic in-depth interview by providing an interface for visualising personal networks.

In this section on the methodological aspect of the project, we explain the rationale behind the selection of the countries in which to conduct the research fieldwork, the characteristics of the sample and process of recruitment, the features of the data-collection tool, the analyses that are planned, the outcomes that are anticipated and the ethical standard of the project.

Selected countries

The study will take place in Switzerland, Spain, Germany and the Netherlands (table 1). The selection of these four countries is based on the following rationale. The interest in the Netherlands is due to its high degree of teleworkability, that is, the technical ability to perform tasks remotely, in which this country was already the European leader before the pandemic.28 Spain, on the other hand, is at the bottom of European countries for teleworking use and is highly polarised in the gendered division of employment, which makes the study of family ties particularly interesting.29 Another research angle emerges in Switzerland, where teleworking has the potential to penetrate much further into its liberal economy, given its significant share of highly skilled workers.30 Germany completes this picture of countries with additional characteristics. Germany has experienced a strong increase in the use of teleworking and has recently started to implement policies to overcome a male breadwinner model, which offers a complementary angle of research.31 Overall, the selection of these countries offers an examination of a diverse set of socioeconomic characteristics on a significant proportion of Europe’s employed population.

Table 1. Selected countries.

| Switzerland | Spain | Netherlands | Germany | |

| Teleworkability | 45% | 34% | 44% | 39% |

| Welfare regimes | Postliberal | Southern | Hybrid | Conservative |

| Types of market economy | Liberal | Mixed | Continental | Continental |

| Family organisation | Multiple | Polarised | Multiple | Multiple |

Sample characteristics: eligibility criteria and recruitment process

Our target is the active population (+18) in occupational sectors with a high degree of teleworking rates (e.g., finance, information and communication, technology, education). Occupational sectors with this feature will be chosen by screening secondary data on the teleworking rate in the first phase of the project. A stratified random sampling by age and gender, with booster quotas of ‘full-time’, ‘hybrids’ and ‘in-presence’ workers, will be put in place to recruit 4400 workers in Switzerland, Spain, Germany and the Netherlands (n=1100 per country). The rationale behind the sample size follows the comparative objectives of the project and the descriptive nature of some of its outputs. As in each country one objective is to identify differences in telework patterns among dissimilar socioeconomic groups, the estimated sample size reflects the necessary breadth and variability required to have sufficient statistical power to apply to each identified group per country. A sample size of 1100 respondents was estimated to achieve these objectives after a power analysis performed with G*Power software.32

The quantitative data collection of WP1 is planned during summer 2024. Respondents will be selected through the research company Ipsos’ Interactive Services branch using a prerecruited group of individuals who have agreed to take part in online research surveys. A double screening procedure will ensure that respondents meet quality checks, controlling for duplicates, IP tracking and validating identity and contact details.

Data collection: features of the data-collection instrument

Quantitative data collection

During WP1, a name generator will be used to elicit respondents’ active family and professional networks.10 A name generator is a standard SNA tool which asks respondents for a list of their personal contacts by responding to one or more so-called ‘name-generating questions’. In order to elicit their professional contacts, respondents will answer to the question, ‘Could you list five of your most important work-related relationships?’ Respondents will be asked to think of different types of colleagues, such as hierarchical superior(s), colleagues under one’s direct responsibility, or colleagues with whom one interacts the most. Moreover, for eliciting family contacts, the generating question will be ‘Could you list the members of your household?’ In addition, WP1 will collect information on the socioeconomic characteristics of the teleworkers, data on the intensity of the work activity, job tasks, occupational positions held, the employer’s attitude towards teleworking and the characteristics of the working environment 33. Standard information on subjective well-being, work–life balance and general health will be collected with validated measures, that is, Utrecht Work-Engagement Scale with nine items (UWES-9) and the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT-12).34 35 The full questionnaire is available in the online supplemental material.

With all this information collected, two different datasets will be built: the first will consist of 4400 teleworkers, while the second will contain data on each of their social relations as the unit of analysis (n=4400 teleworkers * average number of elicited contacts). This design will allow for the construction of a multiplicity of indexes on the composition and structure of personal networks through four main types of information: the characteristics of the teleworkers (ego), the characteristics of their contacts (alters), the characteristics of the relations between the teleworkers and their contacts (ego-alter) and the characteristics of the relations between the contacts themselves (alters-alters).10

Qualitative data collection

During WP2, a subsample of respondents will be selected for qualitative data collection following a sequential mixed-method design.36 A total of 32 in-depth interviews are planned to be performed using the Network Canvas software.27 As mentioned earlier, the use of Network Canvas enriches a classic in-depth interview by providing an interface for visualising personal networks. This graphical projection will then serve as a support to help the discussion with the participants about their biographical experiences and provide directions to further understand the relational dynamic in the context of their telework activities. The interview grid will be developed after analysis of the quantitative data and will focus on investigating the four mechanisms identified in the analytical model: occupational conflicts, social support mechanisms, processes of control over workers and work interruptions. Interviews will be audio recorded and subsequently transcribed. While the quantitative module will allow us to test the hypotheses, the qualitative module will provide a more in-depth understanding of the social mechanisms linking telework and well-being through narrative information on the experiences of teleworkers.37

Data analysis

Using data collected during WP1, the hypotheses will be tested by means of multivariate (ego-level dataset) and multilevel techniques (alter-level dataset). The former will involve integrating indices of the composition and structure of personal networks, for example, the percentage of conflictive ties, in the context of standard analytical techniques such as factorial or principal component analyses, regression analyses or structural equation modelling.10 In the case of the alter-level dataset—that is, data where each contact represents a unit of analysis—multilevel modelling is envisaged due to the dependence on the observations that are extracted from the answers given by each teleworker. These types of procedure are typical of the systematic analysis of ego networks.10 This design will be rendered more robust in WP1 through the collection of data to build an instrumental variable related to the endogeneity of the teleworking activity (eg, the choice of its intensity), such as employers’ general attitudes towards teleworking and their ability to offer it.

Using data collected during WP2, network data collected during the interview with the help of Network Canvas will be analysed using standard qualitative methods tools.37 In SNA, qualitative methods are predominantly employed to comprehend the significance of networks for the individuals involved, as well as to explore the intersubjective meanings that are disseminated, shared and altered within networks. Thematic analyses and qualitative content analysis will therefore be performed to analyse the narrative information in the in-depth interviews.38 These standard narrative data analyses will be enriched by visualising and describing their social networks in terms of their structure and composition. The issues that will be covered during the in-depth interviews are related to the four mechanisms identified in the analytical model: occupational conflicts, social support mechanisms, processes of control over workers and work interruptions.

Expected outcomes

Primary outcome measure: well-being indicators

The primary outcomes are related to well-being markers. The measures include standardised scales and subjective assessments of general health, work–life balance, work engagement and burnout. Indicators on job and telework satisfaction were also included and measured using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘completely satisfied’. To assess burnout, we use the standardised BAT-12. This scale uses a 12-item 5-point Likert scale to capture exhaustion, mental distance, impaired emotional control and impaired cognitive control. The work engagement of teleworkers is assessed using the UWES-9.34 35 UWES-9 includes nine 7-point Likert-scale questions (ranging from never to always) related to vigour, dedication and absorption. In addition to the preceding outcomes, four items investigate the work–life balance of the teleworkers based on Ref 39. Self-rated health markers are also included in the questionnaire, as shown in the online supplemental material.

Secondary outcome measures: the mediating role of personal networks

As mediating factors (or secondary outcome measures), several dimensions of ego-alter relations are studied, such as social support,16 the presence of conflict and unsolicited interruptions40 and the control that contacts may perform over workers’ activities.41 In addition, questions about the social background of each contact are gathered, such as their gender, level of education, nationality and place of residence. Moreover, in a last section, data are collected on relations among the professional contacts themselves (the so-called data on alter-alter ties), that is, if they know each other, share support or have some sort of conflict. A maximum number of five persons will be deployed to collect data on professional networks to allow the computation of structural network measures from such alter-alter ties (e.g., density, betweenness and closeness) and to make them comparable among teleworkers.42

Patient and public involvement

None.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Geneva (CUREG-20230920-292-2). All data will be anonymised in accordance with the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection, as outlined by the Federal Data Protection and Information Commissioner. Participants in the research project will be fully informed of their right to withdraw consent at any point during completion of the questionnaire. Prior to participation, they will receive detailed information sheets and consent forms outlining:

The individuals within the research team responsible for data processing and analysis.

The nature and extent of data collection, processing and analysis.

The objectives behind data processing and analysis.

The voluntary nature of participation and the option to withdraw consent.

The storage and potential secondary analysis of data.

Only participants who provide informed consent will be included in the study. Furthermore, participants will be assured that their data will remain anonymous. They will also be given the opportunity to indicate whether they agree to their data being used anonymously for follow-up or secondary analyses. Data will be stored in the OSF repository, an international platform designed to support scientific research in managing institutional data repositories. OSF adheres to international archiving standards and processes to ensure the long-term preservation and accessibility of data, in line with the FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) .43 Each research dataset will be assigned a Digital Object Identifier along with the associated metadata, facilitating data citation in publications and enabling the traceability of data downloads, reuse and publications. Results will be shared with international organisations and disseminated in scientific journals and conferences.

Discussion

Today, we have fragmented evidence for the positive and negative sides of teleworking. More complex data are needed to provide sounder evidence on its effects on workers' well-being. This project aims to achieve this goal by using SNA.11 This means focusing on telework as a relational phenomenon and studying its influence on the personal networks of teleworkers, an unexplored angle of research in this field of study. Scholars placed great emphasis on the consequences of teleworking for social support, conflicts, work interruptions or control over work activities. The emphasis on these relational aspects makes the lack of use of SNA in telework research a significant gap.3

Using an integrated model of analysis and six starting hypotheses, the project aims to test empirically the effects of telework intensity and environment on personal networks and, in turn, on workers’ well-being. The main originality of this idea is that it multiplies the units of analysis, shifting the focus from the teleworkers as such and building a large database of their family and professional contacts. In the context of a sequential mixed-method design, the quantitative analyses will thus identify the associations between dissimilar socioeconomic features, teleworking patterns and well-being. Following such analysis and the identification of socioeconomic profiles of interest, a subsample of teleworkers will be selected for qualitative data collection to explore narratively, and in diverse socioeconomic profiles of interest, the following mechanisms at the core of the analytical model: professional conflicts, social support mechanisms, processes of control over workers and work interruptions. The mixed-method design allows the question to be approached through different research angles and, through network analysis, permits the links between telework and well-being to be explored not only by looking at teleworkers as such, but also by constructing a large sample of their personal contacts. One limitation of this design is the cross-sectional nature of the data collection. This lack of a longitudinal approach will allow causal mechanisms between telework and well-being to be explored through retrospective information alone.

The most recent forecasts agree that teleworking will increase in the coming years.44 2 45 46 More detailed and complex data are needed to go more deeply into its understanding.3 12 This project is built with this goal in mind and, given all its characteristics, we hope that it will generate new, well thought-out, unique data on the relationship between telework and well-being.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Swiss Network for International Studies (grant number C23018).

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-089232).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Mattia Vacchiano, Email: mattia.vacchiano@unige.ch.

Guillaume Fernandez, Email: guillaume.fernandez@unige.ch.

Eric Widmer, Email: eric.widmer@unige.ch.

Melanie Arntz, Email: melanie.arntz@zew.de.

Manal Azzi, Email: azzi@ilo.org.

Abdi Bulti, Email: Abdi.Bulti@etu.unige.ch.

Nicola Cianferoni, Email: nicola.cianferoni@seco.admin.ch.

Stéphane Cullati, Email: Stephane.Cullati@unige.ch.

Sander Junte, Email: Sander.Junte@uab.cat.

Koorosh Massoudi, Email: koorosh.massoudi@unil.ch.

Oscar Molina Romo, Email: oscar.molina@uab.cat.

Ana Catalina Ramirez, Email: acramirez@ilo.org.

Stephanie Steinmetz, Email: stephanie.steinmetz@unil.ch.

References

- 1.Barrero JM, Bloom N, Davis SJ. The Evolution of Work from Home. J Econ Perspect. 2023;37:23–49. doi: 10.1257/jep.37.4.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Economic Forum Remote working around the world. Feb 1, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/remote-working-around-the-world/ Available.

- 3.Vacchiano M, Fernandez G, Schmutz R. What’s going on with teleworking? a scoping review of its effects on well-being. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0305567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0305567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunde L-K, Fløvik L, Christensen JO, et al. The relationship between telework from home and employee health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:47. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12481-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twenge JM, Joiner TE. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76:2170–82. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung H. The Flexibility Paradox: Why Flexible Working Leads to (Self-) Exploitation. Policy Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fana M, Milasi S, Napierala J, et al. Telework, work organisation and job quality during the COVID-19 crisis: a qualitative study. J R C. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonner KL, Roloff ME. Why Teleworkers are More Satisfied with Their Jobs than are Office-Based Workers: When Less Contact is Beneficial. J Appl Commun Res. 2010;38:336–61. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2010.513998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tett G. The Guardian; 2021. The empty office: what we lose when we work from home.https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/jun/03/the-empty-office-what-we-lose-when-we-work-from-home Available. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarty C, Lubbers MJ, Vacca R, et al. Conducting Personal Network Research: A Practical Guide. New York: Guildford Publishers; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wöhrmann AM, Ebner C. Understanding the bright side and the dark side of telework: An empirical analysis of working conditions and psychosomatic health complaints. New Technol Work Employ. 2021;36:348–70. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin A, Hampton KN. Network Instability in Times of Stability. Sociol Forum (Randolph N J) 2019;34:313–36. doi: 10.1111/socf.12499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78:458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trógolo MA, Moretti LS, Medrano LA. A nationwide cross-sectional study of workers’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impact of changes in working conditions, financial hardships, psychological detachment from work and work-family interface. BMC Psychol. 2022;10:73. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00783-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Zoonen W, Sivunen AE. The impact of remote work and mediated communication frequency on isolation and psychological distress. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2022;31:610–21. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2021.2002299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bollestad V, Amland JS, Olsen E. The pros and cons of remote work in relation to bullying, loneliness and work engagement: A representative study among Norwegian workers during COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1016368. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offer S, Fischer CS. Difficult People: Who Is Perceived to Be Demanding in Personal Networks and Why Are They There? Am Sociol Rev. 2018;83:111–42. doi: 10.1177/0003122417737951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molina O, Godino A, Molina A. El control del teletrabajo en tiempos de Covid-19. aiet . 2021;7:57–70. doi: 10.5565/rev/aiet.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widmer ED, Girardin M, Ludwig C. Conflict Structures in Family Networks of Older Adults and Their Relationship With Health-Related Quality of Life. J Fam Issues. 2018;39:1573–97. doi: 10.1177/0192513X17714507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thulin E, Vilhelmson B, Johansson M. New Telework, Time Pressure, and Time Use Control in Everyday Life. Sustainability. 2019;11:3067. doi: 10.3390/su11113067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown J, Slatyer S, Jakimowicz S, et al. Coping with COVID-19. Work life experiences of nursing, midwifery and paramedic academics: An international interview study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;119:105560. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maillot AS, Meyer T, Prunier-Poulmaire S, et al. A Qualitative and Longitudinal Study on the Impact of Telework in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability. 2022;14:8731. doi: 10.3390/su14148731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergefurt L, Appel-Meulenbroek R, Maris C, et al. The influence of distractions of the home-work environment on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ergonomics. 2023;66:16–33. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2022.2053590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergman MM, editor. Advances in Mixed Method Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birkett M, Melville J, Janulis P, et al. Network Canvas: Key decisions in the design of an interviewer-assisted network data collection software suite. Soc Networks. 2021;66:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sostero M, Milasi S, Hurley J, et al. Teleworkability and the COVID-19 Crisis: A New Digital Divide. Seville: European Commission; 1211. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez-Mira N. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. 2016. La división social y sexual del trabajo en transformación: un análisis de clase en un contexto de crisis. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dingel JI, Neiman B. How many jobs can be done at home? J Public Econ. 2020;189:104235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seeleib‐Kaiser M. The End of the Conservative German Welfare State Model. Soc Policy Adm. 2016;50:219–40. doi: 10.1111/spol.12212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Working From Home Research: Survey of Workplace Attitudes and Arrangements. 2023. https://wfhresearch.com/ Available.

- 34.Schaufeli WB, Desart S, De Witte H. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)-Development, Validity, and Reliability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9495. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The Measurement of Work Engagement With a Short Questionnaire. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66:701–16. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field methods. 2006;18:3–20. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05282260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuhse J, Mützel S. Tackling connections, structure, and meaning in networks: quantitative and qualitative methods in sociological network research. Qual Quant. 2011;45:1067–89. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9492-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreier M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. SAGE Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brough P, Timms C, O’Driscoll MP, et al. Work–life balance: a longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2014;25:2724–44. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.899262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow JSF, Palamidas D, Marshall S, et al. Teleworking from home experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic among public health workers (TelEx COVID-19 study) BMC Public Health. 2022;22:674. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alok S, Kumar N, Banerjee S. Vigour and exhaustion for employees working from home: the mediating role of need for structure satisfaction. IJM. 2024;45:72–88. doi: 10.1108/IJM-04-2022-0168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsden PV. Core Discussion Networks of Americans. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:122. doi: 10.2307/2095397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJJ, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016;3:160018. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bloom N, Han R, Liang J. Hybrid working from home improves retention without damaging performance. Nature New Biol. 2024;630:920–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07500-2. Available. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.International Labour Organization . Healthy and Safe Telework: Technical Brief. Geneva: World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.International Labour Organization . Teleworking Arrangements during the COVID-19 Crisis and Beyond. Geneva: World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Esping-Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kammer A, Niehues J, Peichl A. Welfare regimes and welfare state outcomes in Europe. J Eur Soc Policy. 2012;22:455–71. doi: 10.1177/0958928712456572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hall PA. In: Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences. Scott R, Kosslyn S, editors. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. Varieties of capitalism; pp. 1–15.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118900772 Available. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trampusch C. The welfare state and trade unions in Switzerland: an historical reconstruction of the shift from a liberal to a post-liberal welfare regime. J Eur Soc Policy. 2010;20:58–73. doi: 10.1177/0958928709352539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Visser J. In: Industrial relations in Europe. Visser J, Beentjes M, Gerven M, et al., editors. 2008. The quality of industrial relations and the lisbon strategy; pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- 52.European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Transition Report 2021-22 System Upgrade: Delivering the Digital Dividend. London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Federal Statistical Office Place of work, teleworking. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/work-income/employment-working-hours/working-conditions/place-work.html n.d. Available.