Abstract

Background

Existing researches have predominantly focused on the implications of dynamic alterations in the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index and traditional obesity measures for cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. However, the application of the weight-adjusted waist index (WWI), which incorporates the dynamically changing body composition factors of weight and waist circumference, alongside the TyG index for predicting CVD risk, remains unexplored. This study explores the relationships between baseline TyG-WWI index and its dynamic changes with CVD risk.

Methods

Subjects were drawn from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine the relationships between baseline and longitudinal changes in the TyG-WWI index and CVD risk, quantified through odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The robustness of results was confirmed via subgroup analyses and E-values. Additionally, restricted cubic spline and quartile-based methods evaluated the relationships between baseline and cumulative TyG-WWI indices and CVD risk.

Results

Over two survey waves, 613 CVD events were recorded. Analysis using adjusted multivariable models demonstrated a significant relationship between the cumulative TyG-WWI index and increased CVD risk, with an adjusted OR (95% CI) of 1.005 (1.000, 1.009). Class 2 of the TyG-WWI index change showed greater risk of CVD compared to Class 1, with ORs of 1.270 (1.008, 1.605). However, no significant connection was observed between the baseline TyG-WWI index and CVD risk (OR = 1.007, 95% CI: 0.996, 1.019). These findings were corroborated through extensive sensitivity analyses.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-024-02511-9.

Keywords: Baseline, Cardiovascular disease, China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, Dynamic changes, Triglyceride-glucose index, Weight-adjusted waist index

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) pose a significant global health burden. Despite the marked decline in age-standardised death rates over the past two decades, driven by the identification and proactive management of risk factors, the absolute number of deaths, as well as the incidence and prevalence of CVD worldwide, continue to escalate [1, 2]. Increasingly, the burden of metabolic risk factors, notably obesity, glucose metabolism dysregulation, and lipid abnormalities, has been identified as a key driver of this trend [3]. Given the central role of CVD in global health and the profound impact of metabolic risk factors on its development, there is a pressing need for the rigorous identification and management of CVD-related metabolic risks to enhance cardiovascular health.

Insulin resistance (IR) significantly heightens metabolic risk and is closely connected with various metabolic disorders, including impaired glucose and lipid metabolism, and notably, the accumulation of abdominal fat [4, 5]. Established researches underscore an independent relationship between IR and both the incidence and prognosis of CVD [6–8]. Although the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp stands as the gold standard for IR assessment, its complexity and high cost constrain its routine use in clinical settings [9, 10]. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, merging lipid and glucose levels, offers a practical and effective alternative for assessing IR [10]. Numerous studies have confirmed the strong correlation between the TyG index and both the occurrence and prognosis of CVD, validating its clinical relevance [11–13].

Obesity is a traditional driving risk factor for CVD, particularly in populations characterised by increased abdominal fat, which is strongly correlated with CVD incidence [14–16]. Although body mass index (BMI) is widely used as a straightforward obesity measure, it does not account for variations in fat distribution, contributing to the “obesity paradox” where individuals with a normal BMI may still carry high cardiovascular risk due to abnormal fat distribution [17]. Research, including a meta-analysis, has highlighted waist circumference and related measurements as more effective predictors of CVD development, underscoring the importance of measuring central obesity [18]. Consequently, the weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) has been introduced as a novel obesity metric that combines weight and waist circumference, offering a more precise evaluation of fat distribution and potentially improving risk assessment in clinical settings [19]. Unlike BMI, the WWI focuses specifically on local fat distribution, providing insights that are clinically more relevant than those derived from mere waist circumference measurements, enhancing its utility in predicting cardiovascular health outcomes. Moreover, unlike height, both body weight and waist circumference are dynamic indicators of body composition, providing a more precise reflection of the progressive changes connected with obesity, which enhances their usefulness in monitoring obesity-related health risks.

In this context, assessing the combined effects of IR indicators and obesity metrics on CVD risk is essential. Previous research has suggested that the integration of the TyG index with BMI or waist circumference may serve as a robust biomarker for assessing IR risk [20]. Furthermore, studies have shown that dynamic changes in the TyG index and BMI are connected with the risks of stroke and CVD [21, 22]. Therefore, integrating the IR indicator TyG index with the novel obesity metric WWI may enhance the effectiveness of identifying early signs of CVD.

Despite existing studies suggesting that combining the TyG index with various obesity metrics enhances CVD risk identification, research remains sparse on the impact of the TyG index alongside fat distribution indicators on CVD incidence. This study aims to bridge this gap by utilising large cohort data to evaluate the relationship, focusing on: (i) the impact of the baseline TyG-WWI index on CVD risk; and (ii) the effects of dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index on CVD risk.

Methods

Study design

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is a national, longitudinal cohort study collaboratively executed by Peking University and Wuhan University. This program, designed to investigate aging-related issues within China, seeks to inform policy-making. The methodologies applied in CHARLS have been detailed in prior publication [23]. Initially, in the first Wave from 2011 to 2012, the study utilised a multi-stage sampling technique to recruit participants from 150 counties (cities, districts) and has conducted biennial follow-up surveys since then. Data collection, comprising computer-assisted standardized questionnaires and blood sample collections during the first and third Waves (2015), was rigorously performed under stringent protocols. Ethical approval for this program was granted by the Biomedical Ethics Review Board of Peking University, with approval numbers IRB00001052-11015 and IRB00001052-11014. All participants provided informed consent before inclusion in this program.

Study population

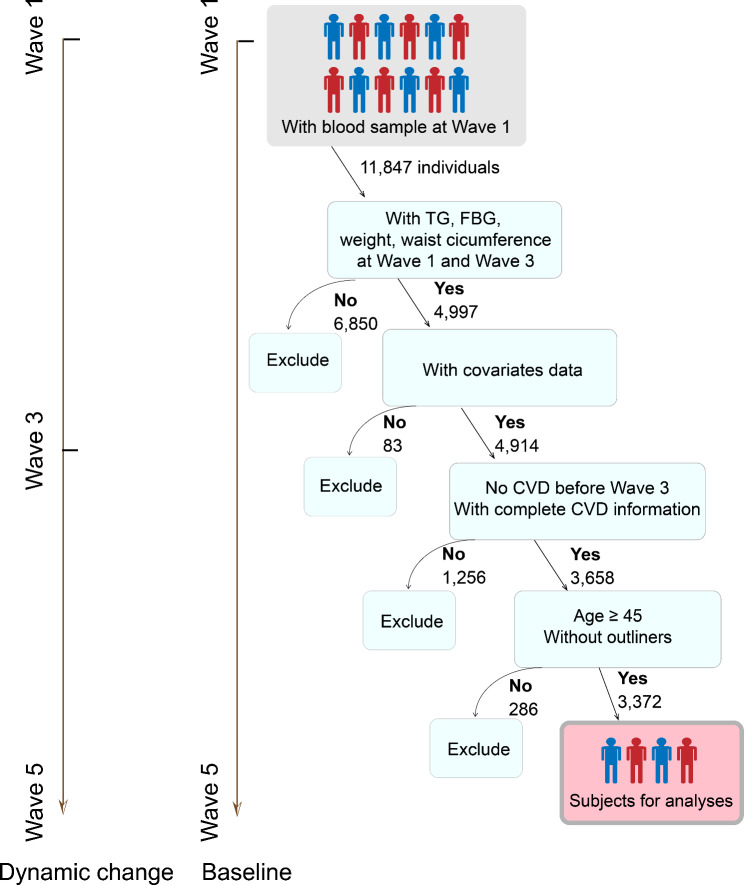

This investigation incorporated only participants with complete datasets. During the initial screening phase, exclusions were applied for several reasons: absence of triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, weight, and waist circumference in Waves 1 and 3 (n = 6,850); missing covariates information (n = 83); presence of CVD or incomplete CVD data at or before Wave 3 (n = 1,061); no CVD information in Waves 4 and 5 (n = 195); participants younger than 45 years (n = 72); and outliers in cumulative TyG-WWI index measurements (n = 214). After these exclusions, 3,372 participants qualified for inclusion to investigate the TyG-WWI index and its link to CVD risk (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study subjects. CVD, cardiovascular disease; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TG, triglyceride

Calculations of exposures

During baseline and follow-up surveys (Waves 1 and 3), participants’ fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, weight, and waist circumference were measured. Utilizing established methodologies from prior studies, the TyG, WWI, TyG-WWI, and cumulative TyG-WWI were computed as follows [19, 22]: (i) TyG = ln [triglycerides (mg/dl) × fasting blood glucose (mg/dl)/2]; (ii) WWI = waist circumference (cm)/√weight (kg); (iii) TyG-WWI = TyG × WWI; (iv) cumulative TyG-WWI = (TyG-WWI wave1 + TyG-WWI wave 3)/2 × time (2015 − 2012).

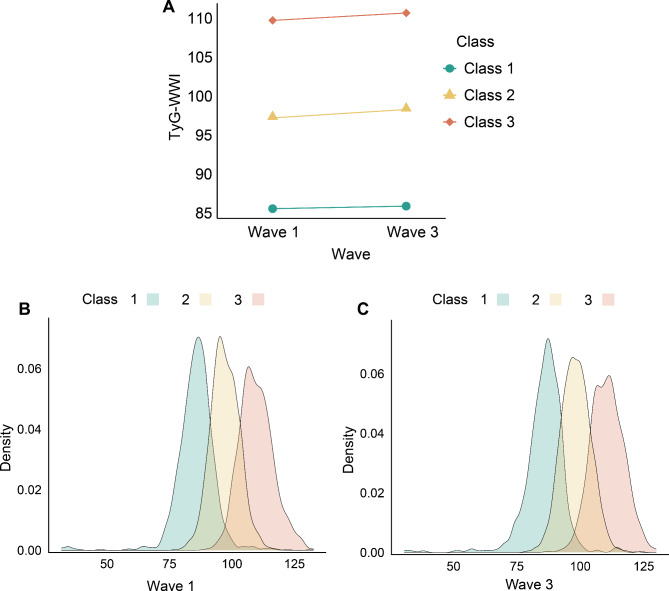

Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) was utilised to assess changes in the TyG-WWI index from Wave 1 to Wave 3, providing a robust statistical approach to identifying distinct latent categories of progression. LPA elucidates relationships between manifest continuous indicators through latent class variables, thus capturing the complex data structure and maintaining the independence of manifest variables [24]. Unlike K-means clustering, which is distance-based and involves subjectively set cluster numbers, LPA determines probabilistic memberships in distinct latent categories, offering a more statistically robust clustering method [24, 25]. The optimal LPA model captured the progression of TyG-WWI index changes across the waves. According to this model, three distinct categories were identified: (i) Class 1, with initial TyG-WWI index levels at 85.57 ± 0.24 and subsequent levels at 85.90 ± 0.24; (ii) Class 2, starting at 97.22 ± 0.14 and rising to 98.29 ± 0.15; and (iii) Class 3, beginning at 109.73 ± 0.25 and increasing to 110.68 ± 0.24 (Table S1 and Fig. 2). Class 1 consistently exhibited low TyG-WWI levels, Class 2 showed moderate levels with slight increases, and Class 3 displayed high levels with a similar upward trend.

Fig. 2.

Categories of change in the TyG-WWI index from Wave 1 to Wave 3. (A) Data visualization for the classes of the change in the TyG-WWI index from Wave 1 to Wave 3. (B) Data distribution of TyG-WWI index in Wave 1 in different classes. C Data distribution of TyG-WWI index in Wave 3 in different classes. TyG: triglyceride-glucose index; WWI: weight-adjusted waist index

Definition of outcome

The primary endpoint was CVD, adhering to the protocols previously established with the CHARLS dataset [26]. CVD events were identified predominantly from self-reported data on diagnoses or treatments related to heart disease and stroke, collected via a computer-assisted standardized questionnaire.

Covariates

Covariates encompassed sociodemographic characteristics, physical examination data, lifestyle factors, blood sample analyses, medical histories, antidiabetic agents, and antihyperlipidemic agents. Sociodemographic factors covered age, gender, educational level, and hukou. Reflecting the demographic profile of predominantly middle-aged and elderly participants with limited historical access to education, educational levels were classified as either “Less than high school” or “High school or above”. Lifestyle assessments focused on smoking and drinking habits, Participants were classified as smokers or non-smokers based on their historical and current smoking habits, and as drinkers or non-drinkers based on the frequency of alcohol consumption, both historically and currently. The physical examination covariate was the mean of three resting pulse rate measurements. Analyses of blood samples measured levels of serum uric acid (SUA), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). History of diabetes and hypertension were determined based on self-reported information, treatment, or clinical measures.

Statistical analyses

For the data characterisation of continuous variables, means ± standard deviations (SD) or medians [interquartile ranges (IQR)] were used, contingent upon the distribution of the data. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Univariate analyses to assess statistical differences between groups were conducted employing one-way ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test, or the Chi-squared test, depending on the nature of the data.

Three logistic regression models were utilised to evaluate the relationships between baseline, cumulative, and changes in the TyG-WWI index and the incidence of CVD. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, educational level, hukou, pulse, SUA, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C. Model 3 was fully adjusted, further incorporating smoking status, drinking status, histories of diabetes, hypertension, antidiabetic agents, and antihyperlipidemic agents.

To ensure the robustness of the findings, several sensitivity analyses were implemented. Firstly, restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression was utilised to investigate non-linear relationships between the baseline and cumulative TyG-WWI indices and CVD risk. Secondly, subgroup analyses were performed to substantiate the robustness of relationships across baseline, cumulative, and change in TyG-WWI index with CVD risk. These analyses were stratified by age (under 60 or 60 and over), gender, educational level, hukou, smoking status, drinking status, abnormal SUA levels (men: >7 mg/dL; women: >6 mg/dL), and histories of diabetes and hypertension. Thirdly, the potential impact of unmeasured confounding factors was assessed using E-values, further validating the study’s results [27]. Finally, the relationship between baseline TyG-WWI and CVD risk was assessed with larger samples.

The integrated discrimination improvement index (IDI) was employed to evaluate the enhancement in model performance of the TyG-WWI for forecasting CVD risk relative to the basic model. Moreover, the relative importance of the TyG-WWI index was evaluated using logistic regression analysis based on their significance.

All statistical procedures were executed using R software, version 4.3.1. The tests were two-sided, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was recognized statistically significant.

Results

Study sample

The baseline characteristics presented in Table 1. The median age of the cohort was 57.00 years (IQR: 51.00–63.00), with females comprising 54.48% of the participants. Based on the changes in the TyG-WWI index, the participants were categorised into three groups: Class 1, encompassing 33.16% of the cohort; Class 2, comprising 46.59%; and Class 3, accounting for 20.26%. Compared to Class 1, participants in Classes 2 and 3 were typically older, had a higher proportion of females, and achieved lower educational levels. These classes exhibited elevated pulse rates, increased levels of TC, LDL-C, and SUA, coupled with decreased HDL-C. Additionally, these groups demonstrated a higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline information according to the categories of change in TyG-WWI index

| Characteristic | Overall | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 3372) | (N = 1118) | (N = 1571) | (N = 683) | ||

| Age, years | 57.00 (51.00–63.00) | 56.00 (50.00–63.00) | 57.00 (51.00–63.00) | 59.00 (54.00–66.00) | < 0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 1837 (54.48%) | 394 (35.24%) | 918 (58.43%) | 525 (76.87%) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1535 (45.52%) | 724 (64.76%) | 653 (41.57%) | 158 (23.13%) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||||

| Less than high school | 3056 (90.63%) | 981 (87.75%) | 1424 (90.64%) | 651 (95.31%) | < 0.001 |

| High school or above | 316 (9.37%) | 137 (12.25%) | 147 (9.36%) | 32 (4.69%) | |

| Hukou | |||||

| Non-agricultural hukou | 454 (13.46%) | 128 (11.45%) | 227 (14.45%) | 99 (14.49%) | 0.054 |

| Agricultural hukou | 2918 (86.54%) | 990 (88.55%) | 1344 (85.55%) | 584 (85.51%) | |

| Pulse, bpm | 71.33 (65.33-78.00) | 69.67 (64.00–76.00) | 71.33 (65.33-78.00) | 73.67 (67.67-81.00) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Non-smokers | 2112 (62.63%) | 549 (49.11%) | 1038 (66.07%) | 525 (76.87%) | < 0.001 |

| Smokers | 1260 (37.37%) | 569 (50.89%) | 533 (33.93%) | 158 (23.13%) | |

| Drinking status, n (%) | |||||

| Non-drinkers | 2309 (68.48%) | 673 (60.20%) | 1104 (70.27%) | 532 (77.89%) | < 0.001 |

| Drinkers | 1063 (31.52%) | 445 (39.80%) | 467 (29.73%) | 151 (22.11%) | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 190.59 (167.78-215.34) | 179.00 (159.28-202.39) | 194.07 (170.88–216.50) | 201.81 (177.06-230.41) | < 0.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 114.82 (94.33-138.02) | 106.89 (89.69-126.42) | 119.85 (99.16-142.46) | 116.75 (93.94-145.36) | < 0.001 |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 49.48 (40.98–60.31) | 55.28 (46.78–66.11) | 48.71 (40.98–58.76) | 42.53 (34.41–51.22) | < 0.001 |

| Serum uric acid, mg/dL | 4.19 (3.49–5.02) | 4.21 (3.45–4.98) | 4.12 (3.46–4.96) | 4.25 (3.60–5.19) | 0.013 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | |||||

| No | 2935 (87.04%) | 1046 (93.56%) | 1387 (88.29%) | 502 (73.50%) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 437 (12.96%) | 72 (6.44%) | 184 (11.71%) | 181 (26.50%) | |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | |||||

| No | 2184 (64.77%) | 854 (76.39%) | 1012 (64.42%) | 318 (46.56%) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 1188 (35.23%) | 264 (23.61%) | 559 (35.58%) | 365 (53.44%) | |

| Antidiabetic agents, n (%) | |||||

| No | 3275 (97.12%) | 1106 (98.93%) | 1536 (97.77%) | 633 (92.68%) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 97 (2.88%) | 12 (1.07%) | 35 (2.23%) | 50 (7.32%) | |

| Antihyperlipidemic agents, n (%) | |||||

| No | 3241 (96.12%) | 1098 (98.21%) | 1515 (96.44%) | 628 (91.95%) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 131 (3.88%) | 20 (1.79%) | 56 (3.56%) | 55 (8.05%) | |

| CVD status, n (%) | |||||

| No | 2759 (81.82%) | 967 (86.49%) | 1269 (80.78%) | 523 (76.57%) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 613 (18.18%) | 151 (13.51%) | 302 (19.22%) | 160 (23.43%) | |

| TyG-WWI wave1 | 95.41 (88.60-103.13) | 85.97 (81.88–89.57) | 96.95 (93.36-101.05) | 109.24 (105.17-113.89) | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WWI wave3 | 96.39 (89.18-104.14) | 86.65 (82.54–90.24) | 98.17 (94.34-102.22) | 110.51 (106.12-115.04) | < 0.001 |

| Cumulative TyG-WWI | 287.64 (267.38-309.41) | 260.21 (249.93–267.20) | 292.20 (284.36-302.29) | 327.99 (320.71-338.22) | < 0.001 |

CVD: cardiovascular disease; TyG: triglyceride-glucose index; WWI: weight-adjusted waist index

The effect of cumulative TyG-WWI index on the incidence of CVD

Over the course of two follow-up waves, 613 participants were diagnosed with CVD, resulting in an incidence rate of 18.18%. Multivariable logistic regression analyses indicated a linear positive relationship between the cumulative TyG-WWI index and CVD risk, with an adjusted OR of 1.005 (95% CI: 1.000, 1.009) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationships between TyG-WWI index and CVD risk

| No.events/total | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Baseline TyG-WWI index | |||||||

| Continuous | 613/3372 | 1.021 (1.012, 1.029) | < 0.001 | 1.012 (1.002, 1.024) | 0.028 | 1.007 (0.996, 1.019) | 0.211 |

| Quartile 1 | 107/843 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Quartile 2 | 146/843 | 1.441 (1.101, 1.891) | 0.008 | 1.277 (0.967, 1.691) | 0.086 | 1.238 (0.936, 1.642) | 0.135 |

| Quartile 3 | 173/843 | 1.776 (1.368, 2.315) | < 0.001 | 1.495 (1.125, 1.992) | 0.006 | 1.385 (1.039, 1.853) | 0.027 |

| Quartile 4 | 187/843 | 1.961 (1.515, 2.549) | < 0.001 | 1.505 (1.085, 2.093) | 0.015 | 1.290 (0.919, 1.813) | 0.142 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.129 | ||||

| Cumulative TyG-WWI index | |||||||

| Continuous | 613/3372 | 1.009 (1.006, 1.012) | < 0.001 | 1.007 (1.003, 1.011) | < 0.001 | 1.005 (1.000, 1.009) | 0.031 |

| Quartile 1 | 111/843 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Quartile 2 | 137/843 | 1.280 (0.977, 1.680) | 0.074 | 1.172 (0.887, 1.550) | 0.264 | 1.140 (0.862, 1.510) | 0.360 |

| Quartile 3 | 165/843 | 1.605 (1.236, 2.090) | < 0.001 | 1.384 (1.040, 1.848) | 0.026 | 1.298 (0.972, 1.739) | 0.078 |

| Quartile 4 | 200/843 | 2.051 (1.593, 2.653) | < 0.001 | 1.673 (1.217, 2.307) | 0.002 | 1.441 (1.039, 2.003) | 0.029 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.023 | ||||

| Change of TyG-WWI index | |||||||

| Class 1 | 151/1118 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Class 2 | 302/1571 | 1.524 (1.234, 1.888) | < 0.001 | 1.340 (1.066, 1.691) | 0.013 | 1.270 (1.008, 1.605) | 0.044 |

| Class 3 | 160/683 | 1.959 (1.531, 2.508) | < 0.001 | 1.563 (1.144, 2.135) | 0.005 | 1.322 (0.959, 1.824) | 0.088 |

a Unadjusted

b Adjusted for gender, age, educational level, hukou, pulse, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and serum uric acid

c Adjusted for gender, age, educational level, hukou, pulse, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum uric acid, smoking status, drinking status, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, antidiabetic agents, and antihyperlipidemic agents

CI: confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; OR: odd ratio; TyG: triglyceride-glucose index; WWI: weight-adjusted waist index

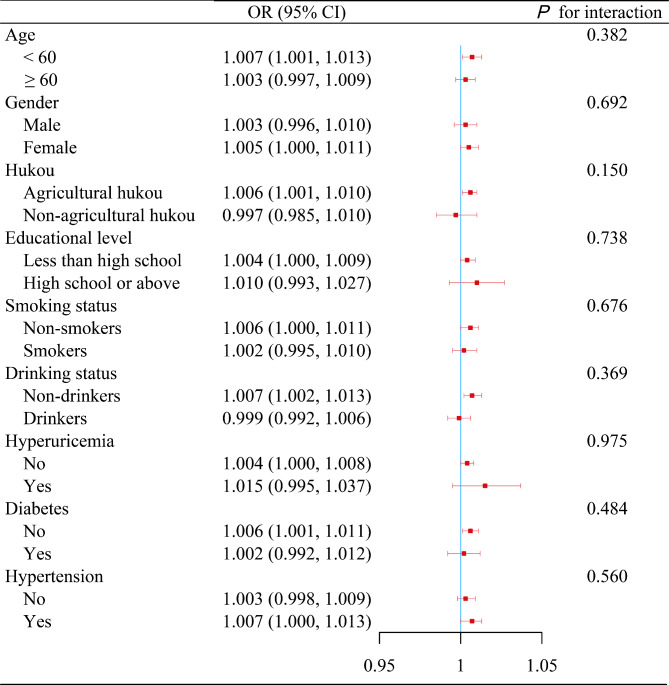

Several sensitivity analyses further affirmed the robustness of these findings: (i) Stratification of the cumulative TyG-WWI index into quartiles revealed progressively elevated CVD risks in higher quartiles, with ORs of 1.140, 1.298, and 1.441 respectively, indicating a significant trend (P for trend = 0.023) (Table 2). (ii) RCS regression analysis substantiated a linear augmentation in CVD risk connected with increasing values of the cumulative TyG-WWI index (Fig. S1A). (iii) No statistically significant interactions emerged from various subgroup analyses (Fig. 3). (iv) The E-value, estimated at 1.053 with a lower confidence limit of 1.023, underscored the substantial robustness of these findings, even accounting for potential unmeasured confounding factors.

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analyses of the relationships between cumulative TyG-WWI index and CVD risk. Data are presented as OR (95% CI) unless indicated otherwise. Adjusted for gender, age, educational level, hukou, pulse, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum uric acid, smoking status, drinking status, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, antidiabetic agents, and antihyperlipidemic agents. The stratified variable was excluded from the model when analyses were stratified by that variable. CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; OR, odd ratio; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; WWI, weight- adjusted waist index

Fig. 4.

Relative importance of cumulative (A), change (B), and baseline (C) TyG-WWI index in CVD risk. DM, history of diabetes; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HTN, history of hypertension; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; UA, uric acid; TC, total cholesterol; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; WWI, weight- adjusted waist index

The effect of change in TyG-WWI index on the incidence of CVD

Following the adjustment for various potential confounders, the impact of changes in the TyG-WWI index on the incidence of CVD was attenuated. Compared with the Class 1, the adjusted ORs for Class 2 and Class 3 were 1.270 (95% CI: 1.008, 1.605) and 1.322 (95% CI: 0.959, 1.824), respectively (Table 2). Further corroboration through sensitivity analyses revealed no statistically significant interactions across any subgroups (Table 3). Additionally, the E-values for the independent effects of the changes in TyG-WWI index for Classes 2 and 3 on CVD risk were 1.505 and 1.565, respectively, with their lower confidence intervals noted at 1.067 and less than one.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses of the relationships between change of TyG-WWI index and CVD risk

| Subgroup | Change of TyG-WWI index | P for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||

| Age | ||||

| < 60 | 1 (Reference) | 1.276 (0.934, 1.753) | 1.708 (1.092, 2.672) | 0.290 |

| ≥ 60 | 1 (Reference) | 1.260 (0.889, 1.796) | 1.090 (0.687, 1.732) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 (Reference) | 1.281 (0.929, 1.769) | 1.036 (0.564, 1.858) | 0.581 |

| Female | 1 (Reference) | 1.247 (0.884, 1.782) | 1.402 (0.924, 2.146) | |

| Hukou | ||||

| Agricultural hukou | 1 (Reference) | 1.329 (1.037, 1.710) | 1.499 (1.064, 2.113) | 0.173 |

| Non-agricultural hukou | 1 (Reference) | 1.067 (0.547, 2.136) | 0.570 (0.203, 1.574) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Less than high school | 1 (Reference) | 1.250 (0.978, 1.603) | 1.290 (0.923, 1.806) | 0.988 |

| High school or above | 1 (Reference) | 1.521 (0.716, 3.288) | 1.329 (0.338, 4.874) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Non-smokers | 1 (Reference) | 1.266 (0.929, 1.739) | 1.431 (0.963, 2.138) | 0.768 |

| Smokers | 1 (Reference) | 1.296 (0.906, 1.857) | 1.028 (0.557, 1.865) | |

| Drinking status | ||||

| Non-drinkers | 1 (Reference) | 1.492 (1.111, 2.017) | 1.593 (1.078, 2.362) | 0.416 |

| Drinkers | 1 (Reference) | 0.975 (0.663, 1.436) | 0.910 (0.496, 1.651) | |

| Hyperuricemia | ||||

| No | 1 (Reference) | 1.295 (1.023, 1.646) | 1.283 (0.922, 1.785) | 0.305 |

| Yes | 1 (Reference) | 0.575 (0.147, 2.250) | 2.220 (0.438, 12.28) | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 1 (Reference) | 1.362 (1.065, 1.745) | 1.469 (1.025, 2.103) | 0.787 |

| Yes | 1 (Reference) | 1.127 (0.516, 2.600) | 1.054 (0.450, 2.580) | |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 1 (Reference) | 1.210 (0.905, 1.623) | 1.266 (0.802, 1.985) | 0.892 |

| Yes | 1 (Reference) | 1.433 (0.968, 2.152) | 1.505 (0.931, 2.456) | |

Data are presented as OR (95% CI) unless indicated otherwise

Adjusted for gender, age, educational level, hukou, pulse, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum uric acid, smoking status, drinking status, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, antidiabetic agents, and antihyperlipidemic agents. The stratified variable was not included in the model when stratifying by itself

CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; OR, odd ratio; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; WWI, weight- adjusted waist index

The effect of baseline TyG-WWI index on the incidence of CVD

Multivariable adjustments indicated that the baseline TyG-WWI index had a negligible impact on CVD risk, with OR of 1.007 (95% CI: 0.996, 1.019) (Table 2). Subsequent sensitivity analyses, which included stratification of the baseline TyG-WWI index into quartiles and RCS regression, also failed to reveal any significant correlations with CVD risk (Table 2 and Fig. S1B). Additionally, no significant interactions were observed in subgroup analyses (Fig. S2). The E-value estimate of 1.063, with a lower bound of the confidence interval below one, further underscores the limited independent impact of the baseline TyG-WWI index on CVD risk. Besides, analyses utilising an expanded sample size in this study did not affect the statistical significance (Table S2).

Enhanced model performance and relative importance of the TyG-WWI index in CVD

Comparative analyses using the IDI revealed that the cumulative TyG-WWI index emerged as the most potent predictor of CVD, achieving IDI of 0.0015 (95% CI: 0.0001–0.0029), surpassing the change of TyG-WWI index (IDI 0.0013, 95% CI: 0.0001–0.0025), the baseline TyG-WWI index (IDI 0.0005, 95% CI: -0.0003-0.0013), the cumulative TyG-BMI index (IDI 0.0003, 95% CI: 0.0000-0.0006), and the baseline TyG-BMI index (IDI 0.0003, 95% CI: 0.0000-0.0006) (Table 4). Furthermore, comparisons were also made between TyG-WWI index, TyG index, and WWI. Utilising a logistic regression model, the relative significance of each variable was evaluated by root mean square error loss after permutations. The results underscored that the cumulative TyG-WWI index was the most significant, overshadowing the baseline TyG-WWI index and changes in the TyG-WWI index (Fig. 4). Notably, the relative importance of the TyG-WWI index surpassed those of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking status, drinking status, and history of diabetes.

Table 4.

Comparison of integrated discrimination improvement index

| Characteristics | IDI | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative index | |||

| Cumulative TyG vs. Basic model | 0.0002 | (-0.0006, 0.0009) | 0.640 |

| Cumulative WWI vs. Basic model | 0.0014 | (0.0002, 0.0026) | 0.023 |

| Cumulative TyG-WWI vs. Basic model | 0.0015 | (0.0001, 0.0029) | 0.035 |

| Cumulative TyG-BMI vs. Basic model | 0.0003 | (0.0000, 0.0006) | 0.028 |

| Change of index | |||

| TyG-WWI change vs. Basic model | 0.0013 | (0.0001, 0.0025) | 0.034 |

| Baseline index | |||

| Baseline TyG vs. Basic model | 0.0000 | (-0.0004, 0.0004) | 0.973 |

| Baseline WWI vs. Basic model | 0.0006 | (-0.0002, 0.0014) | 0.131 |

| Baseline TyG-WWI vs. Basic model | 0.0005 | (-0.0003, 0.0013) | 0.216 |

| Baseline TyG-BMI vs. Basic model | 0.0003 | (0.0000, 0.0006) | 0.030 |

Basic model adjusted for gender, age, educational level, hukou, pulse, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum uric acid, smoking status, drinking status, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, antidiabetic agents, and antihyperlipidemic agents

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; IDI: integrated discrimination improvement index; TyG: triglyceride-glucose; WWI: weight-adjusted waist index

Discussion

Utilising data from the CHARLS cohort, which targeted individuals aged 45 and above, our investigation uncovered two notable findings. Firstly, both the cumulative and the changes in the TyG-WWI index independently exerted a significant influence on CVD risk. Secondly, the baseline TyG-WWI index demonstrated no significant correlation with CVD risk. Extensive sensitivity analyses reinforced the robustness of these observations. The practical implications of this research are profound. By monitoring dynamic changes in fasting blood glucose, triglyceride, waist circumference, and weight, clinicians can effectively identify individuals at elevated risk of CVD.

Our research underscores the potential risk posed by dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index for the development of CVD. Accumulating evidence indicates that dynamic changes in IR pose a distinct and vital risk factor for CVD [6–8]. IR induces a spectrum of metabolic anomalies such as dyslipidaemia and glucose dysregulation, which directly contribute to the pathogenesis of CVD and escalate various connected risk factors [28]. In the state of IR, elevated levels of free fatty acids lead to increased lipid synthesis while lipid breakdown and oxidation are impaired, thus disturbing lipid metabolism [29]. Moreover, IR affects the contractility and relaxation capacity of blood vessels, reducing arterial elasticity and enhancing stiffness, thus elevating the incidence of CVD [30, 31]. The TyG index, a contemporary marker for evaluating IR, has proven effective in predicting both the emergence and outcomes of CVD [12, 13]. Previous investigations, including the Kailuan study involving 49,579 subjects undergoing three health assessments, have validated the connection between TyG index fluctuations and increased CVD risk [32]. This study revealed that persistently high TyG index values significantly correlate with a higher incidence of CVD [32]. Furthermore, another analysis using a multi-trajectory model confirmed that individuals with consistently high TyG trajectories face a heightened risk of CVD, even when leading generally healthy lifestyles [33]. These insights affirm the importance of monitoring changes in the TyG index to identify individuals at an elevated risk of CVD proactively.

This investigation merges the TyG index with the WWI to assess their correlation with CVD risk. Evidence increasingly indicates that particularly abdominal obesity, characterized by elevated triglyceride lipoproteins, significantly contributes to heightened CVD risk [17]. Studies have established that the WWI supersedes conventional obesity markers such as BMI, body shape index, and waist-to-height ratio in predicting CVD incidence and mortality [19, 34]. As individuals age, metabolic levels change, highlighting the relevance of monitoring changes in weight and waist circumference to assess metabolic shifts. Our results confirm that dynamic changes in the combined TyG index and WWI are substantially linked to CVD risk. Supporting literature suggests that incorporating the TyG index with various obesity metrics reveals that dynamic changes in the combination of TyG and waist circumference correlate more significantly with CVD risk than traditional measures like BMI and waist-to-height ratio [35]. This emphasizes the clinical importance of focusing on measurements that demonstrate significant dynamic alterations when evaluating CVD risk. Unlike BMI and waist-to-height ratio, which incorporate the less variable component of height, WWI represents a more dynamically sensitive anthropometric measure.

This study found no significant connection between the baseline TyG-WWI index and CVD risk, contrasting with findings from the UK Biobank, which identified a notable positive correlation in a cohort of 403,335 over 8.1 years [36]. Similarly, another nine-year study involving 21,750 participants documented a significant effect of the baseline WWI on CVD risk [37]. Conversely, Cui et al. [38] observed no significant linear relationship between the baseline TyG index and CVD risk when combined with traditional obesity indices in a study of 7,115 middle-aged and older adults. The absence of a significant relationship in our analysis may be attributed to several factors: the specific demographic focus on middle-aged and older individuals, the relatively small sample size, and the shorter duration of follow-up. Furthermore, while the IDI analysis showed no substantial improvement in model performance, effect size analysis indicated that the baseline TyG-WWI index was less effective compared to the baseline WWI alone. This suggests that the baseline TyG-WWI index may offer limited advantages for detecting CVD risk in baseline assessments.

Further subgroup analyses within distinct subgroups confirmed the baseline TyG-WWI index’s lack of significant connection with CVD risk, consistent with the overall analysis. However, analyses identified that significant correlations existed between the cumulative and change of TyG-WWI index and CVD risk in certain subgroups. It was observed that subgroups lacking significant findings typically had smaller sample sizes, which may have led to inadequate statistical power, thereby influencing the detection of significance. Consequently, future research should focus on enlarging these subgroup analyses or conducting prospective studies that assess the relationships of cumulative and change of TyG-WWI indices with CVD risk in targeted populations. This approach would significantly refine the evaluation of the TyG-WWI index’s risk prediction capabilities and its applicability to diverse demographic categories.

This study leverages a national, large-scale cohort and employs multiple analytical methods to comprehensively assess the impacts of baseline and dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index on CVD risk. The data collection was meticulously executed by trained professionals following stringent protocols, which enhances the reliability of the data. Despite its merits, the study faces several potential limitations. Firstly, its observational design precludes definitive causal inferences between the TyG-WWI index and CVD risk. Secondly, reliance on self-reported data to define CVD may introduce reporting bias. It is noteworthy that diagnostic data were corroborated through retrospective analysis of prior self-reports during follow-ups, lending greater validity to the findings. Moreover, while extensive adjustments were made for a broad range of variables, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Calculated E-values suggest that unmeasured confounders are unlikely to significantly alter the results. Additionally, subgroup analyses indicated that connections between dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index and CVD risk were statistically significant in specific subgroups only, likely due to the small sample sizes. Future research should aim to confirm these observations in larger, targeted population samples. Furthermore, despite the dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index are significantly associated with CVD risk, the IDI analysis reveals that its contribution to enhancing model performance is modest. Therefore, it should be integrated with other risk factors for the early identification of CVD risk. The evaluation of dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index is constrained by the fact that blood tests were conducted only during Waves 1 and 3; however, the use of LPA to identify changes in the TyG-WWI index helps to address some limitations connected with data.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal that dynamic changes in the TyG-WWI index, rather than baseline measurements, significantly correlate with the onset of new CVD events. Individuals exhibiting persistently high TyG-WWI index levels are at a considerably increased risk of developing CVD. Accordingly, it is essential to introduce early and effective interventions for those with consistently high TyG-WWI values to reduce their CVD risk. This underscores the importance of vigilant monitoring and management of TyG-WWI fluctuations in the prevention of CVD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Chenglin Duan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing– original draft, and Writing– review & editing. Meng Lyu: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, and Writing– original draft. Jingjing Shi: Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, and Writing– original draft. Xintian Shou: Formal analysis, Supervision, validation, and Writing– review & editing. Lu Zhao: Methodology, Visualization, and Writing– original draft. Yuanhui Hu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, validation, and Writing– review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by Scientific and technological innovation project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (ZZ15-XY-LCQ-02) and Central High level Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital Clinical Research and Achievement Transformation Ability Enhancement Project (HLCMHPP2023082).

Data availability

Online repositories contain the datasets used in this investigation. The names of the repositories and accession numbers can be found at https://charls.pku.edu.cn/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this program was granted by the Biomedical Ethics Review Board of Peking University, with approval numbers IRB00001052-11015 and IRB00001052-11014. All participants provided informed consent before inclusion in this program.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chenglin Duan, Email: 20230941377@bucm.edu.cn.

Yuanhui Hu, Email: huiyuhui55@sohu.com.

References

- 1.Mensah GA, Fuster V, Murray CJL, Roth GA. Global Burden of Cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990–2022. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2350–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trends. World Heart Observatory (2019). Accessed 28 Aug 2024. https://world-heart-federation.org/world-heart-observatory/trends/

- 3.Mensah GA, Fuster V, Roth GA. A heart-healthy and stroke-free world: using data to inform global action. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SH, Reaven G. Obesity and insulin resistance: an ongoing saga. Diabetes. 2010;59:2105–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S-H, Park S-Y, Choi CS. Insulin resistance: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46:15–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louie JZ, Shiffman D, McPhaul MJ, Melander O. Insulin resistance probability score and incident cardiovascular disease. J Intern Med. 2023;294:531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J-H, Jeon S, Joung B, Lee HS, Kwon Y-J. Associations of Homeostatic Model Assessment for insulin resistance trajectories with Cardiovascular Disease incidence and mortality. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2023;43:1719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian X, Chen S, Xu Q, Xia X, Zhang Y, Wang P, et al. Magnitude and time course of insulin resistance accumulation with the risk of cardiovascular disease: an 11-years cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrannini E, Mari A. How to measure insulin sensitivity. J Hypertens. 1998;16:895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerrero-Romero F, Simental-Mendía LE, González-Ortiz M, Martínez-Abundis E, Ramos-Zavala MG, Hernández-González SO, et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quiroga B, Muñoz Ramos P, Sánchez Horrillo A, Ortiz A, Valdivieso JM, Carrero JJ. Triglycerides-glucose index and the risk of cardiovascular events in persons with non-diabetic chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:1705–12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36003671/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Zhang Q, Xiao S, Jiao X, Shen Y. The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: evidence from NHANES 2001–2018. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sánchez-Íñigo L, Navarro-González D, Fernández-Montero A, Pastrana-Delgado J, Martínez JA. The TyG index may predict the development of cardiovascular events. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016;46:189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keihani S, Hosseinpanah F, Barzin M, Serahati S, Doustmohamadian S, Azizi F. Abdominal obesity phenotypes and risk of cardiovascular disease in a decade of follow-up: the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238:256–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan H, Li X, Zheng L, Chen X, Lan Q, Wu H, et al. Abdominal obesity is strongly associated with Cardiovascular Disease and its risk factors in Elderly and very Elderly Community-dwelling Chinese. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després J-P, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e984–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després J-P, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S, Shai I, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:715–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Koning L, Merchant AT, Pogue J, Anand SS. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular events: meta-regression analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:850–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park Y, Kim NH, Kwon TY, Kim SG. A novel adiposity index as an integrated predictor of cardiometabolic disease morbidity and mortality. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J, Kim B, Kim W, Ahn C, Choi HY, Kim JG, et al. Lipid indices as simple and clinically useful surrogate markers for insulin resistance in the U.S. population. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huo R-R, Zhai L, Liao Q, You X-M. Changes in the triglyceride glucose-body mass index estimate the risk of stroke in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li F, Wang Y, Shi B, Sun S, Wang S, Pang S, et al. Association between the cumulative average triglyceride glucose-body mass index and cardiovascular disease incidence among the middle-aged and older population: a prospective nationwide cohort study in China. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha P, Calfee CS, Delucchi KL. Practitioner’s guide to latent class analysis: methodological considerations and common pitfalls. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e63–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford T, Lipson J, Miller L. Spiritually grounded character: A latent profile analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1061416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.He D, Wang Z, Li J, Yu K, He Y, He X, et al. Changes in frailty and incident cardiovascular disease in three prospective cohorts. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1058–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in Observational Research: introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill MA, Yang Y, Zhang L, Sun Z, Jia G, Parrish AR, et al. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. 2021;119:154766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yazıcı D, Sezer H. Insulin resistance, obesity and lipotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:277–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salomaa V, Riley W, Kark JD, Nardo C, Folsom AR. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and fasting glucose and insulin concentrations are associated with arterial stiffness indexes. The ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis risk in communities Study. Circulation. 1995;91:1432–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell GF, Hwang S-J, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Pencina MJ, Hamburg NM, et al. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;121:505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Zuo Y, Qian F, Chen S, Tian X, Wang P, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index variability and incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou H, Ding X, Lan Y, Chen S, Wu S, Wu D. Multi-trajectories of triglyceride-glucose index and lifestyle with Cardiovascular Disease: a cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dallongeville J, Bhatt DL, Steg PHG, Ravaud P, Wilson PW, Eagle KA, et al. Relation between body mass index, waist circumference, and cardiovascular outcomes in 19,579 diabetic patients with established vascular disease: the REACH Registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu X, Xu W, Song T, Wang X, Wang Q, Li J, et al. Changes in the combination of the triglyceride-glucose index and obesity indicators estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Che B, Zhong C, Zhang R, Pu L, Zhao T, Zhang Y, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index and triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as potential cardiovascular disease risk factors: an analysis of UK biobank data. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S, Yu J, Wang L, Zhang X, Wang F, Zhu Y. Weight-adjusted waist index as a practical predictor for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and non-accidental mortality risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;34:2498–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui C, Qi Y, Song J, Shang X, Han T, Han N, et al. Comparison of triglyceride glucose index and modified triglyceride glucose indices in prediction of cardiovascular diseases in middle aged and older Chinese adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Online repositories contain the datasets used in this investigation. The names of the repositories and accession numbers can be found at https://charls.pku.edu.cn/.