Abstract

Background

Asthma is a chronic, heterogeneous disease characterized by airway inflammation. Asthma exacerbations significantly increase the disease burden, necessitating new therapeutic approaches. Emerging evidence suggests probiotics, through the gut-lung axis, may benefit asthma management by modulating immune responses and reducing inflammation.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to PRISMA guidelines and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023480098). A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase was conducted up to March 2024. Inclusion criteria encompassed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating probiotic interventions in asthma patients. Statistical analysis was done using RevMan 5.3, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated, and heterogeneity assessed using I2 statistics.

Results

Twelve RCTs, comprising 1401 participants, met the inclusion criteria. The probiotic strains investigated included various Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Meta-analysis revealed significant improvements in asthma control test scores (OR 1.18, 95% CI: 1.18–3.64, p = 0.0001) following probiotic supplementation. Probiotics also improved fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in one study, but pooled FeNO and eosinophil data were not statistically significant (p = 0.46 and p = 0.29, respectively). One study observed fewer asthma exacerbations in the probiotic group (24/212) compared to placebo (67/210), with no difference in exacerbation duration.

Conclusion

Probiotic supplementation may be beneficial in improving asthma symptom control with no significant impact on lung function indices or eosinophil levels. Probiotics can be a potential adjunctive therapy in asthma management, particularly for asthma symptom control.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13223-024-00922-7.

Keywords: Asthma, Probiotics, Efficacy, Randomized controlled trials, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation [1]. In 2019, there were an estimated 262 million prevalent cases of asthma globally, with an age-standardized prevalence of 3415.53 per 100,000 population [2]. The age-standardized mortality rate due to asthma globally in 2019 was 5.8 per 100,000 population [2]. Though symptoms of asthma get commonly resolved either spontaneously or through medication, certain patients may face exacerbations, which carry the potential for life-threatening outcomes [3]. These exacerbations markedly increase the disease's burden. One emerging area of interest is probiotics as a potential adjunctive therapy for asthma. Probiotics are "live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host" [4]. The gut-lung axis represents a bidirectional communication pathway between the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems [5]. Disruption of the gut microbiota composition, known as dysbiosis, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various respiratory diseases, including asthma [5]. Understanding this axis offers new insights into disease pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions. Modulating the gut microbiome through probiotics and diet holds promise for various systemic conditions and improving overall health [6]. The mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of probiotics in asthma are multifaceted. Probiotics can interact with the host immune system, promoting the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory mediators [7].

Moreover, probiotics may strengthen the epithelial barrier in the gut and respiratory tract, reducing the translocation of allergens and pathogens and subsequently attenuating airway inflammation [7, 8]. A diverse array of probiotic strains, like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, are under investigation for their potential role in asthma management [9, 10]. Research on lung microbiota suggests its transient nature in health, influenced by adjacent body sites and the environment. Gut-lung microbiota interactions impact respiratory health, with potential for novel therapies through improved understanding and functional guild identification via 'omics' approaches [5]. Recent randomized controlled trials show evidence that probiotics have a role in asthma control and reducing exacerbations [11, 12]. Hence, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to study the beneficial impact of probiotics on asthma.

Methodology

Registration and protocol

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting the findings [13]. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42023480098) before searching.

Objectives

The research question for this systematic review is: 'What is the efficacy of probiotics in managing bronchial asthma?' The research question was deconstructed into the PICO framework, where 'population' refers to individuals diagnosed with bronchial asthma, irrespective of age, gender, or ethnicity. The 'intervention' entails the administration of probiotics, while the 'comparison' encompasses standard treatments or placebo. The primary 'outcome' is the efficacy and safety of probiotics in managing bronchial asthma. The systematic review aims to comprehensively evaluate the existing evidence regarding the potential benefits and risks associated with probiotic supplementation in individuals with bronchial asthma.

Eligibility criteria

The studies were considered eligible to be included according to the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Randomized controlled trials, (2) Individuals diagnosed with bronchial asthma, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, or severity of the condition, (3) Studies involving the administration of probiotics as an intervention, regardless of the dosage forms (e.g., capsules, tablets, powders, fermented foods), (4) Studies with a comparison group, which may include a placebo, standard treatment for asthma, or no treatment (5) Studies reporting relevant outcome measures related to the efficacy and safety of probiotics in managing bronchial asthma, and (6) Studies published in any language with no restriction on publication date.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies involving probiotic interventions combined with other treatments or interventions unrelated to asthma management will be excluded, (2) Animal studies, (3) Non-retrievable articles or abstract-only papers.

Information sources and search strategy

We have performed a systematic literature search to select eligible articles published in the electronic bibliographic databases from the establishment until March 2024. We systematically implemented an advanced electronic search in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase to search for eligible studies. The search strategy in the above database was performed using the keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms ‘Probiotics’, ‘Bronchial asthma’, and ‘Probiotic agent’ using ‘AND’ and ‘OR.’ We limited the search to English publications.

Study selection process and data extraction

The studies were screened by title and abstracts followed by full-text articles based on predefined criteria. Two independent reviewers (D.B. and T.B.) performed the study selection, and disagreements were resolved by mutual consultation with a third reviewer (M.K.M). A well-defined data extraction sheet was employed. Data from the final selected studies included authors’ names, year of publication, study design, sample size, study groups, and clinical outcomes. One reviewer (T.B.) extracted the data in a standardized extraction sheet, and the other reviewer (D.B.) checked for accuracy. Discussions or consultations with a third reviewer (M.K.M) resolved disagreements.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane risk of bias (CROB) assessment tool was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Two independent reviewers (D.B. and T.B.) performed the quality assessment, and any disagreements were settled through consensus or discussion with a third reviewer (M.K.M.).

Data synthesis

All the extracted information about the study was synthesized qualitatively and presented narratively. The data extracted from the included studies are represented in tabular form. The data synthesized in this review summarized the efficacy of current evidence for probiotic intervention supplementation in asthma.

Statistical analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis using Review Manager Software (RevMan, version 5.3 for Windows; The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. To evaluate statistical heterogeneity, we have used the I2 statistics. Studies were subjected to the fixed-effects model if no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 ≤ 50% or P ≥ 0.10).

Results

Study selection

A total of 2828 records have been identified after a systematic literature search from the abovementioned databases. Prior to the title and abstract screening, 1284 duplicate records were removed. Subsequently, 41 full-text articles were retrieved. Five articles were retrieved from a manual search as well. Full-text screening was performed on 46 articles based on our review eligibility criteria. Finally, 12 studies were incorporated into our review [11, 12, 14–23] (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the screening and selection process

Study characteristics

All 12 studies included were placebo-controlled randomized trials. The types of probiotic intervention used have been mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Type of probiotic intervention | Number of participants in the intervention group | Number of participants in the placebo group | Duration of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. 2022*[14] | Lactobacillus reuteri CCFM1040 | 4 | 4 | 8 weeks |

| Drago et al. 2022[11] | Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS01 (DSM 22775), Bifidobacterium breve B632 (DSM 24706) | 212 | 210 | 16 weeks |

| Liu et al. 2021[12] | Bifidobacterium lactis Probio-M8 | 30 | 26 | 3 months |

| Satia 2021[15] | Limosilactobacillus reuteri DSM-17938 | 114 | 4 weeks | |

| Huang et al. 2018**[16] | Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus fermentum & both of their combination | 114 | 38 | 3 months |

| Giudice et al. 2017[17] | Bifidobacterium longum BB536, Bifidobacterium infantis M-63, Bifidobacterium breve M-16 V | 20 | 20 | 2 months |

| Liu et al. 2016[18] | Clostridium butyricum | 15 | 14 | 6 months |

| Smith et al. 2016[19] | Lactobacillus acidophilus CUL60 (NCIMB 30157) and CUL21 (NCIMB 30156), Bifidobacterium bifidum CUL20 (NCIMB 30153) and B. animalis (var lactis) CUL34 (NCIMB 30172) | 652 | 632 | 6 months |

| Chen et al. 2010[20] | Lactobacillus gasseri PM-A0005 | 55 | 56 | 8 weeks |

| Gutkowski et al. 2010[21] | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidrum and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus | 22 | 24 | 12 weeks |

| Rose et al. 2010 [22] | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | 65 | 46 | 12 weeks |

| Giovannini et al. 2007[23] | Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 | 98 | 77 | 6 months |

*Values are taken for only asthma patients

**Huang 2018 has three intervention arms of two types of probiotics and their combination

Asthma exacerbation

Drago et al. 2022, reported a reported a significantly reduced proportion of patients in the probiotic group who experienced asthma exacerbations, with 24 out of 212 patients in the probiotic group and 67 out of 210 in the placebo group (11). However, the mean asthma exacerbation duration was similar in both groups, which were 3.3 ± 2.45 days and 3.3 ± 2.57 days in the probiotic and placebo groups, respectively. They have used a multi-strain probiotics formulation of Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS01 and Bifidobacterium breve B632.

Asthma control test

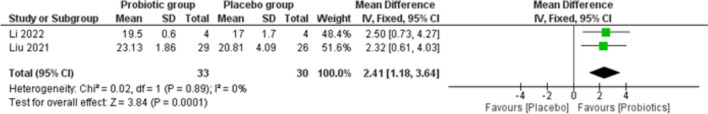

Of all the included studies, Liu et al. 2021 and Li et al. 2022 reported asthma control test scores after the probiotic intervention [12, 14]. Both studies showed improved asthma control test scores after the probiotic intervention. Li et al. 2022 used Lactobacillus reuteri CCFM1040 as an intervention, whereas Liu et al. 2021 used Bifidobacterium lactis Probio-M8 as their study intervention [12, 14].

The fixed effect model was chosen due to the absence of statistical heterogeneity among studies (I2 ≤ 50% or P ≥ 0.10). The pooled analysis of two studies with 63 asthma patients showed a significant p-value of 0.0001 and an OR of 1.18 with a 95% CI: 1.18–3.64. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for asthma control test

Airway inflammation biomarker

Out of all the studies included, we could extract the data on fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) from Liu et al. 2016 and Liu et al. 2021 [18, 24]. While Liu et al. 2016 did not conclude any significant impact of the probiotic intervention on FeNO, Liu et al. 2021 concluded that the probiotic-treated group improved FeNO compared to the placebo group [18, 24]. However, the pooled analysis revealed statistically non-significant (p-value of 0.46) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for FeNO

Liu et al. 2016 found lower eosinophils at six months of Clostridium butyricum intervention than the placebo group [18]. Likewise, Liu et al. 2021 observed with Bifidobacterium lactis Probio-M8 intervention [24]. However, from pooled analysis, we could not find a statistically significant (p-value of 0.29) impact of probiotics intervention on the eosinophilia condition (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for eosinophils

Lung function indices

Out of all the studies included, we could extract the data on forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) from Liu et al. 2016, Liu et al. 2021, Chen et al. 2010, and Gutkowski et al. 2010, none of the studies concluded any significant impact of probiotic intervention on FEV1. Since the data units were not uniform across the studies a meta-analysis could not be performed. [12, 18, 20, 21]

We also extracted data on peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) from Liu et al. 2016, Liu et al. 2021 and Chen et al. 2010. All three studies found no significant impact of probiotic intervention on PEFR. [12, 18, 20]

Adverse effects

Out of all the studies included, we could extract data on adverse effects from Li et al. 2022, Drago et al. 2022, Satia et al. 2021, Huang et al. 2018, Smith et al. 2016, Chen et al. 2010. Only Satia et al. 2021 reported that one patient developed a mild upper respiratory tract infection during the treatment period and one subject developed mild transient nausea with no serious adverse events. However, no adverse effects were reported with probiotics intervention in other studies [11, 14–16, 19, 20]

Risk of bias assessment

We have graded the risk of bias assessment as low, high, and unclear by using the CROB tool (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of all studies included

| Study (Ref) | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. 2022 [14] | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Drago et al. 2022 [11] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Liu et al. 2021 [12] | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Satia et al. 2021 [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Huang et al. 2018 [16] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Giudice et al. 2017 [17] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Liu et al. 2016 [18] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Smith et al. 2016 [19] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Chen 2010 [20] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Gutkowski et al. 2010 [21] | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Rose et al. 2010 [22] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Giovannini et al. 2007 [23] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

Discussion

Our systematic review included 12 studies of 1401 asthmatic patients who received probiotics as adjuvant therapy. We observed various probiotic strains used in asthma treatment, among which the most common probiotic genus was Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

Several strains of Lactobacillus have been studied for their potential benefits in asthma. Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus reuteri, and Lactobacillus gasseri are among the most investigated strains [9, 25, 26]. Studies have shown that Lactobacillus can modulate immune responses and reduce airway inflammation in the context of allergic asthma [9, 25, 26]. Lactobacillus species and their components (peptidoglycan etc.) enhance respiratory health via complex mechanisms. The gut-lung axis is critical, where oral probiotics activate immune cells and cytokines in the gut, migrating to the lungs to boost immunity [27]. Bifidobacteria are the predominant inhabitants of the human gut microbiota, playing a crucial role in gut homeostasis and immune function [11]. Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Bifidobacterium longum are among the most studied strains of asthma [11, 28]. Bifidobacteria have been shown to enhance mucosal barrier function, stimulate the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and regulate T-cell responses, thereby exerting immunomodulatory effects that may benefit asthma patients [10].

From meta-analysis, we found that probiotic supplementation is associated with improvements in asthma control. Our pooled analysis supports the efficacy of probiotics in improving asthma control test scores. Despite the use of different probiotic strains (Lactobacillus reuteri CCFM1040 and Bifidobacterium lactis Probio-M8), the observed improvements suggest probiotics can modulate the host immune system and maintain the microbial balance in the gut [7]. It modifies the host's Th1/Th2 balance by producing cytokines that enhance the Th1 pathway and suppress the Th2 pathway, which is associated with asthma and other allergic conditions [29].

Enhanced asthma control is associated with reduced symptom burden, decreased risk of exacerbations, and improved quality of life for individuals with asthma [1]. Probiotics may be a valuable adjunctive therapy for optimizing asthma management and improving patient outcomes, particularly for individuals with suboptimal disease control. The absence of statistical heterogeneity among the studies suggests a consistent effect of probiotics on asthma control, despite differences in probiotic strains used.

The meta-analysis revealed no significant impact of probiotics on T2-inflammation biomarkers and blood eosinophil level reduction. Factors such as participant characteristics, probiotic strain type, and intervention durations might have influenced the overall findings of the pooled analysis.

We observed no adverse drug reactions associated with probiotics as adjuvant therapy. The diversity of probiotic strains used across studies reflects the wide range of commercial microbial species being explored for their potential benefits in asthma management [11, 14–24]. It demonstrates the complexity of the gut-lung axis and the potential for various microbial species to influence immune responses and airway inflammation in individuals with asthma.

We acknowledge that there are not many studies on any specific probiotic strain for treating asthma from where we could have narrowed it down to a particular strain for the meta-analysis. Therefore, we warrant that more controlled trials are needed to investigate specific probiotic strains’ potential role in reducing asthma exacerbations and improving asthma control. The robust evidence in this area could find the place of probiotics adjuvant therapy in asthma management guidelines.

Conclusion

This systematic review highlights the potential of probiotics in managing asthma by reducing exacerbations and improving asthma control. Evidence suggested significant improvements in asthma control test scores and a potential reduction in exacerbation rates, with no significant impact on lung function. Although there were trends toward reduced eosinophil levels, the pooled analysis lacked statistical significance, and no adverse events were reported. Therefore, comparative studies on strain-specific efficacy are required.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to Manipal Universal Press for their expert language editing assistance.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- MeSH

Medical subject headings

- CROB

Cochrane risk of bias

- OR

Odds ratios

- CI

Confidence interval

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- PEFR

Peak expiratory flow rate

Author contributions

D.B conceptualized the review question. D.B and T.B did the systematic search, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. D.B and T.B interpreted the extracted data. T.B performed the meta-analysis. D.B and T.B wrote the manuscript. M.K.M, S.S.M, and A.K.M critically evaluated the manuscript. All the authors approved the final draft of the article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. None.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma - GINA. 2023 GINA Main Report, 2023. https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/; Accessed 15 Apr 2024.

- 2.Wang Z, Li Y, Gao Y, Fu Y, Lin J, Lei X, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of asthma and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Respir Res. 2023;24:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitouni MO, Al-Moamary MS, Coussa ML, Riachy M, Mahboub B, AlHuraish F, et al. Challenges and recommendations for the management of asthma in the Middle East and Africa. Ann Thorac Med. 2022;17:71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:506–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DLA, Cooper MA, Morrison M, Hugenholtz P, et al. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut–lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quaranta G, Guarnaccia A, Fancello G, Agrillo C, Iannarelli F, Sanguinetti M, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and other gut microbiota manipulation strategies. Microorganisms. 2022;10:2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadrifar S, Abbasi-Dokht T, Forouzandeh S, Malek F, Yousefi B, Salek Farrokhi A, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotic supplementation in patients with asthma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol Off J Can Soc Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;19:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maldonado Galdeano C, Cazorla SI, Lemme Dumit JM, Vélez E, Perdigón G. Beneficial effects of probiotic consumption on the immune system. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;74:115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spacova I, Van Beeck W, Seys S, Devos F, Vanoirbeek J, Vanderleyden J, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotic prevents airway function deterioration and promotes gut microbiome resilience in a murine asthma model. Gut Microbes. 2020;11:1729–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sangkanjanavanich S, Pradubpongsa P, Mitthamsiri W, Sangasapaviliya A, Boonpiyathad T. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 efficacy in patients with uncontrolled asthma: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:790–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drago L, Cioffi L, Giuliano M, Pane M, Amoruso A, Schiavetti I, et al. The probiotics in pediatric asthma management (PROPAM) study in the primary care setting: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial with Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS01 (DSM 22775) and Bifidobacterium breve B632 (DSM 24706). J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:3837418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu A, Ma T, Xu N, Jin H, Zhao F, Kwok LY, et al. Adjunctive probiotics alleviates asthmatic symptoms via modulating the gut microbiome and serum metabolome. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9:e00859-e921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PRISMA statement, 2020. https://www.prisma-statement.org/; Accessed 29 Apr 2024.

- 14.Li L, Fang Z, Lee Y, Zhao J, Zhang H, Peng H, et al. Efficacy and safety of lactobacillus reuteri ccfm1040 in allergic rhinitis and asthma: a randomized. Placebo-Controlled Trial Front Nutr. 2022;9:862934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satia I, Cusack R, Stevens C, Schlatman A, Wattie J, Mian F, et al. Limosilactobacillus reuteri DSM-17938 for preventing cough in adults with mild allergic asthma: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:1133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang CF, Chie WC, Wang IJ. Efficacy of Lactobacillus administration in school-age children with asthma: a randomized. Placebo-Controlled Trial Nutrients. 2018;10:1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miraglia Del Giudice M, Indolfi C, Capasso M, Maiello N, Decimo F, Ciprandi G. Bifidobacterium mixture (B longum BB536, B infantis M-63, B breve M-16V) treatment in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis and intermittent asthma. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Chen F, Qiu SQ, Yang LT, Zhang HP, Liu JQ, et al. Probiotics enhance the effect of allergy immunotherapy on regulating antigen specific B cell activity in asthma patients. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:5256–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith TDH, Watt H, Gunn L, Car J, Boyle RJ. Recommending oral probiotics to reduce winter antibiotic prescriptions in people with asthma: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen YS, Lin YL, Jan RL, Chen HH, Wang JY. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of lactobacillus on asthmatic children with allergic rhinitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:1111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutkowski P, Madaliński K, Grek M, Dmeńska H, Syczewska M, Michałkiewicz J. Effect of orally administered probiotic strains Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in children with atopic asthma. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2011;35:233–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose MA, Stieglitz F, Köksal A, Schubert R, Schulze J, Zielen S. Efficacy of probiotic Lactobacillus GG on allergic sensitization and asthma in infants at risk. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovannini M, Agostoni C, Riva E, Salvini F, Ruscitto A, Zuccotti GV, et al. A randomized prospective double blind controlled trial on effects of long-term consumption of fermented milk containing lactobacillus casei in pre-school children with allergic asthma and/or rhinitis. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu A, Ma T, Xu N, Jin H, Zhao F, Kwok LY, et al. Adjunctive probiotics alleviates asthmatic symptoms via modulating the gut microbiome and serum metabolome. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9: e0085921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forsythe P, Inman MD, Bienenstock J. Oral treatment with live lactobacillus reuteri inhibits the allergic airway response in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen PC, Hsieh MH, Kuo WS, Wu LS, Kao HF, Liu LF, et al. Moonlighting glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein of Lactobacillus gasseri attenuates allergic asthma via immunometabolic change in macrophages. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du T, Lei A, Zhang N, Zhu C. The beneficial role of probiotic lactobacillus in respiratory diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 908010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciprandi G, Tosca MA, Drago L. Probiotics in asthma management: fiction or truth? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2023;19:457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuccotti G, Meneghin F, Aceti A, Barone G, Callegari ML, Di Mauro A, et al. Italian Society of Neonatology. Probiotics for prevention of atopic diseases in infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2015;70:1356–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.