Abstract

The proliferation of fake news on social media platforms has become a significant concern, influencing public opinion, political decisions, and societal trust. While much research has focused on the technological and algorithmic factors behind the spread of misinformation, less attention has been given to the psychological drivers that contribute to the creation and dissemination of fake news. Cognitive biases, emotional appeals, and social identity motivations are believed to play a crucial role in shaping user behaviour on social media, yet there is limited systematic understanding of how these psychological factors intersect with online information sharing. Existing studies tend to focus on individual aspects of fake news consumption, such as susceptibility to misinformation or partisan biases, leaving a gap in understanding the broader psychological mechanisms behind both the creation and dissemination of fake news. This systematic review aims to fill this gap by synthesizing current research on the psychological factors that influence social media users’ involvement in dissemination and creation of fake news. Twenty-three studies were identified from 2014 to 2024 following the PRISMA guidelines. We have identified five themes through critical review and synthesis of the literature which are personal factors, ignorance, social factors, biological process, and cognitive process. These themes help to explain the psychological factors contributing to the creation and dissemination of fake news among social media users. Based on the findings, it is evident that diverse psychological factors influence the dissemination and creation of fake news, which must be studied to design better strategies to minimize this issue.

Keywords: Fake news, Creation, Dissemination, Social media users, Psychological factors

Background

A social phenomenon known as “fake news” shows up in the framework of social interactions. It refers to information that has been widely shared without a factual foundation, verification, or explanation, whether on purpose or accidentally [1]. This issue has raised concerns across various academic fields, including social sciences such as sociology and journalism, as well as disciplines like psychology, communication studies, political science, and information technology. Researchers in these fields are concerned about the widespread impact of fake news on public opinion, mental health, political polarization, and the integrity of information shared on digital platforms. Each discipline examines the phenomenon from different angles, such as its influence on behaviour, media credibility, societal trust, and the role of algorithms in amplifying misinformation [2]. Spread through word-of-mouth and quickly spread by the development of social media and technology, misinformation demonstrates traits including fission dissemination, high propagation speed, broad effect, and significant impact. While it is common to find fake news on illegal websites, well-known social media platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram, Twitter, and others are important conduits for the quick dissemination of unverified material. According to Lazer et al., the spread of false information and fake news on social media platforms not only alarms the public and endangers people’s physical and mental well-being, but it also seriously disrupts the security and management of the social system [3].

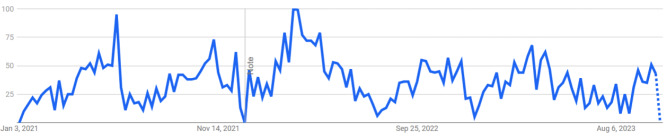

Based on Fig. 1, a Google trend analysis of the creation and dissemination of fake news for the past three years (2021–2023) shows that global fake news creation and dissemination showed a high percentage in 2021 compared to 2022 and 2023. The analysis likely involved tracking data from social media platforms, news websites, and fact-checkers, focusing on metrics such as shares, retweets, and geographic spread. Analytical tools like sentiment analysis and machine learning could have been used to detect and categorize fake news by themes such as political or health-related misinformation. The interpretation would highlight peaks in dissemination during events like elections or pandemics, regional differences in spread, and platform-specific trends, revealing how different factors and response efforts influenced the global distribution of fake news. As a result, 2021 marked a turning point for online information warfare, with fake news linked to COVID-19 being the most widespread issue globally. Upon reviewing the pertinent literature, it was discovered that almost all the research on fake news is related to detecting techniques that use machine learning algorithms to analyse social media feeds and platform features [4]. While a significant body of research has explored the spread of misinformation, much of the existing literature has focused on content analysis of social media communications, often overlooking the underlying psychological mechanisms that drive user engagement with fake news. Contrary to this narrow focus, several studies have examined audience behaviour, employing diverse methods such as surveys, experiments, and network analysis to investigate why individuals share fake news (5–6). Other research on the subject included sharing the history of the fake news that was identified, examining the core content of the material, and analysing information found in comments and articles [7–10].

Fig. 1.

Global patterns for the dissemination of fake news in 2021–2023

Other research concentrated on language traits and writing style, the sharing history of the fake news that was identified, the analysis of the content’s core ideas, and information found in articles and comments [11]. Fact-checking websites is another technical approach to detecting bogus news. To further understand the evolution pattern of the creation and dissemination of fake news in social networks, we need to understand the psychological factors that contribute to the following. Psychological elements, such as cognitive biases, emotional responses, and belief systems, fundamentally shape how individuals perceive, evaluate, and interact with information. Unlike structural or technological factors, which may facilitate the spread of fake news, psychological factors directly impact decision-making processes at the individual level. For instance, cognitive biases like confirmation bias lead people to accept and share information that aligns with their pre-existing beliefs, regardless of its accuracy [5]. Emotions such as fear, anger, or excitement can drive impulsive reactions, further amplifying the spread of misinformation [12]. Given that fake news often capitalizes on these emotional and cognitive tendencies, understanding the psychological underpinnings provides a deeper insight into why certain news is created and widely shared. Additionally, while factors like social network structure and algorithmic influence are significant, they often operate through psychological mechanisms. Therefore, a focus on psychological factors offers a more fundamental understanding of the issue, allowing for more targeted interventions to mitigate the spread of misinformation.

Psychological factors are multidimensional. They are defined as the factors such as core beliefs, emotions, anxieties, and self-perceptions that influence an individual’s behaviour and well-being. These psychological factors determine our reaction toward various situations and thus affect our behaviour [13]. Psychological factors are associated with the dissemination of fake news across social media platforms [14]. For example, emotions are one of the psychological factors that may impact how an individual reacts to bogus news. For instance, studies have shown that emotions like fear or anger significantly impact how individuals assess the credibility of information and their likelihood to share it without verification [12, 15]. Cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias, also shape how individuals interact with fake news, as they are more likely to believe and spread information that aligns with their pre-existing beliefs [5]. By exploring each dimension in depth, researchers can better understand how these psychological factors interrelate and influence the spread of misinformation, thereby identifying where future research is needed.

According to Martel et al., the following factors influence people’s willingness to believe fake news [16]. Firstly, certain moods connected with joy or higher motivation are often related with a negative propensity to detect deceit and a tendency to believe misleading information; on the other hand, certain moods linked to melancholy or lower drive are usually linked with doubt and disbelief. Second, one is more inclined to rely upon heuristic cues to choose whether to believe the facts when one is upset than when one is angry. Third, anxiety increases one’s willingness to entertain opposing viewpoints, but anger decreases this proclivity. Besides that, altruism is also another psychological factor that can be a driving force to help others without seeking compensation for oneself. It is acknowledged as one of the key elements contributing to the dissemination of false information [17, 18]. Altruism and anxiety are related when someone’s desire to assist others stems from concern for their welfare. Two types of research are relevant when considering altruism as a factor in a person’s vulnerability to deceit. The first category investigates the drive to gain as a factor. In addition, motivation is also another psychological factor that encompasses the fundamental reasons that individuals create and disseminate fake news [19]. The motive provided here is not only concerned with individual motivations to disseminate fake news but rather with why fake news is formed in the first place.

In terms of individual-level factors, including beliefs and other cognitive states, some empirical research indicates that recipients of false political news are unlikely to have their opinions changed because of cognitive biases that keep them from accepting stories that contradict their ideas [20]. This, however, may be unique to the extremely divisive field of politics, since studies indicate that disinformation can be corrected in less divisive fields, such as health [21]. The personal consequences of misinformation might also show themselves as people sharing these messages on social media without even assessing them. Studies have indicated that people disseminate news articles on social media platforms due to the fact that it fulfils their desire for influence and social interaction [22]. This is because some erroneous statements are sensational, and people use social media with a hedonistic perspective, which may make sharing such messages more lucrative [23].

Although there have been studies examining psychological variables that contribute to the creation and spread of fake news, no research has directly explored the specific relationship between psychological factors and the production and dissemination of fake news. Due to the enormous number of studies exploring aspects of disinformation and the creation of fake news, a review of psychological factors on fake news can help us understand the extent to which psychological factors contribute to the creation and dissemination of fake news. It will also help us to identify individuals with those factors which will assist in the reduction of creation and dissemination of fake news. Hence, this study aims to carry out an extensive review of psychological factors, which contribute to the creation and dissemination of fake news among social media users.

Methodology

This review has been registered under PROSPERO (CRD42024551727). The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) 2020 guideline [24] was followed in conducting the systematic literature review search. This review focuses on the motivations behind the production and spread of fake news rather than how to spot it. The identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion phases made up the four stages of this systematic review’s analysis. The Covidence tool were utilized to complete this study.

Identification of literature

During the identification stage, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and PsycINFO are the four databases that were searched. These databases were chosen to ensure that a wide range of fake news dissemination and creation studies from various geographical regions were included, as these databases provide publications that fulfil some level of acceptable research criteria. Four keywords were used to create search terms: (a) psychological factors; (b) dissemination; (c) creation, and (d) fake news. To capture the vast amounts of literature in each domain, each keyword was matched with its synonyms. These terms and derivatives were then converted into search strings, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| Category | Web of Science | Scopus | PsycINFO | PubMed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keyword 1: Psychological factors (independent variable) | |||||

| Synonyms: Personality, motivation, emotion, learning, socialization, attitudes, beliefs. | |||||

| Search String (#1): Psychological factors∗ OR emotion∗ OR “learning∗ approach∗” OR “attitudes∗” OR “beliefs∗” OR “socialization∗” OR “personality∗ factor∗” | |||||

| Keyword 2: Dissemination (dependent variable) | |||||

| Synonyms: Spreading, circulation, distribution, dispersal, publicizing, passing on, propagation | |||||

| Search String (#2): Spreading∗ OR circulation∗, “distribution∗” OR “dispersal∗” OR “publicizing∗” OR “passing on∗” OR “propagation∗” | |||||

| Keyword 3: Creation (dependent variable) | |||||

| Synonyms: Design, formation, making, building. | |||||

| Search String (#3): Design∗ OR formation∗ OR “making∗”, OR “building∗”. | |||||

| Keyword 4: Fake news (dependent variable) | |||||

| Synonyms: Misinformation, false information, disinformation, false rumor. | |||||

| Search String (#3): Misinformation∗ OR false information∗ OR “disinformation∗” OR “false rumor∗”. | |||||

| #1, #2 and #4 | 102 | 75 | 55 | 8 | 240 |

| #1, #3 and #4 | 88 | 26 | 34 | 4 | 152 |

| Excluded by screening by reading titles, abstracts, and keywords | 134 | 60 | 50 | 4 | 245 |

| Removal of duplicates in the endnote | 17 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 33 |

| Excluded with inclusion/exclusion criteria | 37 | 26 | 25 | 3 | 91 |

| Total retained for review | 2 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 23 |

Eligibility and screening

Subsequently, the literature that was discovered was screened in phases. Examining the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the selected studies from the entire search string which contained all four keywords, and their synonyms was the first step. All retrieved papers were exported onto a reference manager (RIS) which was consecutively imported into Covidence, to assist with the title and abstract as well as the full-text review. We screened the titles and abstracts to shortlist relevant papers. Successively, full texts were assessed for aptness. Subsequently, the article’s entire content was carefully examined to determine whether it met the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 2. First, only English-language articles were reviewed to streamline the review process and prevent content misunderstandings resulting from translation issues. The second is a timeline that runs from 2014 to 2024, or a decade. Furthermore, since psychological elements are the main explanatory variable in the study, only research papers that examine or address any psychological issues related to the creation and dissemination of fake news were considered.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Inclusive | Exclusive |

|---|---|---|

| Year Duration | 2014–2024 | Articles before 2014 |

| Language | English/Malay article | Not English/Malay articles |

| Country | All countries | No exclusion |

| Study | All research articles | Review articles |

| Context | Creation and dissemination of fake news | Content related to factors in believing fake news |

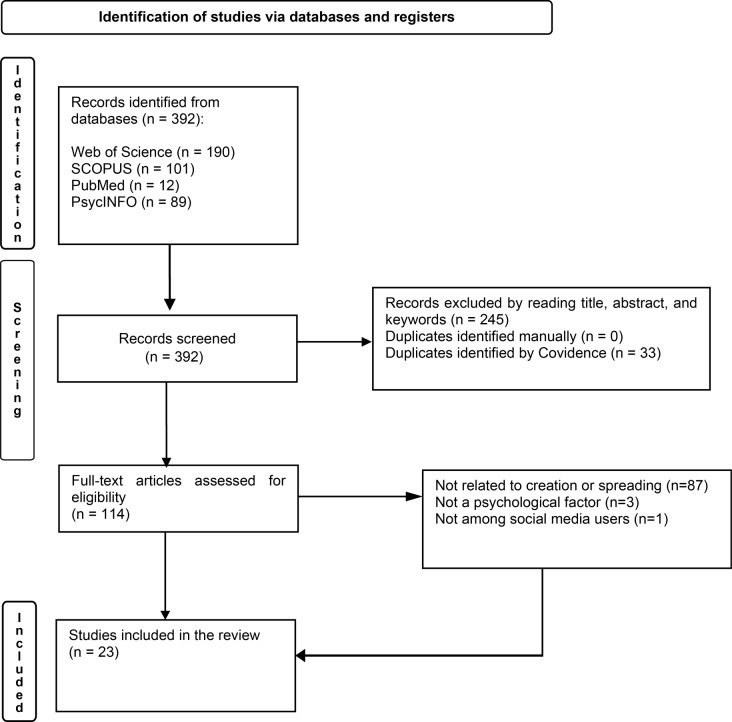

The current review classified psychological components as elements that impact an individual’s behaviour and overall well-being, including basic beliefs, emotions, worries, and self-perceptions. These psychological elements influence our behaviour by dictating how we respond to different circumstances. Furthermore, to prevent erroneous interpretations of the findings, papers that fail to explicitly pinpoint the psychological elements connected to the production or spread of false information were disregarded. A total of 392 papers were found through the initial literature search using the literature databases, and they were filtered according to their title and abstracts. As such, 137 articles were found and chosen for additional screening after the initial screening. Following that, 33 articles were omitted because they were duplicates, together 91 articles were omitted as they didn’t address the dissemination and creation of false information. The remaining articles were examined in their entirety to evaluate if they complied with the inclusion criteria. As a result, 23 pertinent papers were chosen as the best fit to be included in this systematic review and to achieve the goal of this study, which was to determine the variables linked to unfavourable bystander behaviour. The procedure is shown in Fig. 2 PRISMA flow diagram.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA Flowchart

Quality assessment

The Covidence software was used in this study to evaluate the quality of the included research. The study design, methodological rigor, sample size, and risk of bias domains were among the evaluation criteria that were predetermined in accordance with the research question. The evaluation of studies was based on how well they adhered to established quality standards in their respective domains. For documenting assessments on different bias domains, such as reporting bias, attrition bias, detection bias, performance bias, and selection bias, Covidence offered an organised framework. Before the formal assessment, a calibration exercise was carried out to guarantee consistency and dependability in the quality assessment procedure. Through consensus sessions, reviewers addressed differences and improved their comprehension of the assessment criteria. Using Cohen’s kappa coefficient to measure inter-rater reliability, significant agreement was found (κ = 0.80). Every included study was assessed in relation to the predetermined standards, and assessments of the potential for bias were noted. With few cases of notable bias, most studies showed moderate to high methodological quality overall.

Results

The data was analysed and interpreted using 23 peer-reviewed publications. The primary findings of all the chosen research focused on the psychological elements that influence the production or spread of false information. Table 3 provides an overview of the general features of the included studies as well as their research findings. A study used the longitudinal design [25], while the rest of the study assessed were cross-sectional studies. A large sample size was employed in twenty-two studies using a quantitative technique while only small sample size was included in two studies using a qualitative approach [26, 27]. The studies were from Malaysia [17, 19], Nigeria (18, 28–29), United Kingdom [25, 26], United States of America [30–35], India (27, 36–37), France [38], Vietnam [39], China [40, 41], Israel [42], Korea [43], and Singapore [44]. In this review, we had found different types of psychological factors, which can contribute to creation and sharing fake news among social media users. However, out of the 23 articles included in this study, only one article [32] explored on the creation of fake news.

Table 3.

Study Description

| Author | Psychological factors | Methodology | Findings | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opuke & Omar [18] | Altruism, socialization, motivation | Nigerian sample (n = 385), cross-sectional design | Social media users’ reasons for sharing information were found to be the second most significant factor after altruism. Socialization was found to be a predictor of the dissemination of misleading information regarding COVID-19. | Failed to investigate if distribution of bogus news would be mitigated by age, gender, income, or cultural background. |

| Talwar et al. [36] | Fear of missing out (FoMO), and social media fatigue |

Cross-sectional design 1022 social media users |

Online trust is positively correlated with self-disclosure; yet, distributing bogus news online is negatively correlated with social media fatigue and fear of missing out (FoMO). | Influenced by the methodologically biassed cross-sectional design. |

| Wei et al. [28] | Social media literacy | 1068 user |

• Social media trust and status-seeking were more influential in influencing the dissemination of false information. • Social media literacy plays a crucial role in moderating the association between sharing of bogus news. |

This study employed non-probability sampling, not every participant had an equal chance of being chosen. |

| Rodrigo et al. [26] | Motive | Qualitative, 21 interviews with social media users | Motivation is a key component affecting the public’s susceptibility to fake news and its ability to spread. | To investigate the functions performed by various sources (e.g., micro celebrities vs. friends and relatives vs. regular A-list celebrities). |

| Balakrishnan et al. [17] | Altruism, FoMO, pass time | 869 respondents, Malaysians and above 18 years old | Altruism and ignorance significantly predict the behaviour, pass time, and FoMO were found to be insignificant. | Methods of gathering data in order to guarantee a larger sample size of responders. |

| Omar et al. [19] | Altruism, information sharing, socialization | Malaysian sample (n = 451) | The dissemination of fake news is significantly impacted by both extrinsic and intrinsic variables. | The study just considers the Malaysian situation. |

| Ali et al. [30] | Emotion | 813 participants were recruited online, through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Service (MTurk) | In the anger condition compared to the fear condition, those with neutral attitudes towards vaccinations shown a noticeably higher self-expression motivation to spread the false information. | Participants in each category of the independent variables were exposed to a single stimulus under a single message design. |

| Aman et al. [37] | Motivation | 356 respondents | Government laws and the pleasure of missing out (JOMO) have a negative effect on the dissemination of bogus news. | The focus of the research is on social media users. |

| Micheal et al. [31] | Information sharing | 207 participants | Credibility positively influenced sharing behavior, regardless of condition. | Limited sample setting. |

| Ahmed & Metwaly [32] | Motivations | Male 59.2% (n = 802), females 40.8% of the sample (n = 502), between 19 and 35 years old (58.5%). | The main motivations were toobtain relevant information and reduce anxiety. | Types of misinformation and the results may differ in other countries. |

| Nurbakova et al. [38] | Personality characteristics | The tweets were posted between March 30, 2020, and July 13, 2020. 2,159,932 people were discovered to have published tweets in English in this dataset. | Contributors to information streams regarding COVID-19 treatments frequently show a propensity for high Neuroticism scores. | Sentiment analysis and user personality factors are used to forecast information distortion inside cascades. |

| Sharma et al. [27] | Individual moral consciousness | Respondents in India (n = 310) | Sharing political deepfake videos is positively moderated by individual moral consciousness. | Qualitative research is required to analyze the deepfake sharing phenomenon. |

| Oberiri & Bahiyah [29] | Socialization | Nigerian social media users (n = 650) | Information-seeking, parasocial interaction, and perceived herd are important indicators of the spread of bogus news. However, there was no discernible impact of status-seeking on the spread of false information. | Drew its sample from a single nation, Nigeria. |

| Anu & Fransesca [33] | Emotion | Undergraduate students (n = 363) from social science courses | Users’ tendency to share news is strongly influenced by their perceptions of the emotions sparked by the news item. | Limited range of age. |

| Thanh et al. [30] | Generosity, amusement, socializing, and instantaneous information exchange | Intentional sampling in a cross-sectional survey (n = 200) conducted in Vietnam | The dissemination of fake news is positively and significantly impacted by altruism, entertainment, socialization, self-promotion, and fast information sharing. | Does not fully reflect on targeted population’s characteristics. |

| Buchanan [25] | Personality trait | 4 longitudinal studies (total n = 2,634) | Demographic factors (male gender, lower age, and lower education) and personality traits (lower extraversion and neuroticism, higher conscientiousness and agreeableness, and greater neuroticism) were sporadically and weakly correlated with self-reported likelihood of sharing. | It was not measured how much time was spent reading and responding to the misinformation stimuli. |

| Lawson & Kakkar [34] | Role of Conscientiousness | 488 participants (MAge = 39.6 years old) | Respondents with poor conscientiousness almost primarily drove cross-party sharing behaviour. | To gather a participant sample that is nationally representative, it could be required to generalize the findings. |

| Chuai & Zhao [40] | Anger | Eight datasets were collected on Weibo from 2011 to 2016 (with409,865 users), employed five basic cross-cultural.emotions. There are three methods for calculating the distribution of emotions: deep neural networks, classical machine learning models, and emotion lexicons. | Fake news spreads more easily online and is positively correlated with increased rage. | Effects of false information spreading throughout various social structures. |

| Li [41] | Personality traits | 452 university students | The Big Five personality qualities of conscientiousness, emotional instability, and extroversion are positively correlated with fear of COVID-19, and this fear positively influences the spread of rumours online. | Limited generalization of the results. |

| Lobato et al. [35] | Individualdifferences in political orientation | There are two orthogonal models that predict an individual’s propensity to spread false information on social media. | According to both models, political belief plays a significant influence in predicting the propensity to spread various types of misinformation, most notably conspiracy theories. | The main political ideas of individuals, and particularly their propensities for social domination, are significant factors. |

| Vered et al. [42] | Attitudes and beliefs | 503 valid questionnaires were collected. | The more favourable attitudes and ideas people have about information and its dissemination, the more likely it is that they will do so. | It is difficult to draw broader conclusions about other communities. |

| Han et al. [43] | Anger | Between April 9 and April 13, 513 South Koreans participated in an online survey. | Anger and sharing fake news are highly correlated. | As with testing multiple populations to determine the representative dependability of the instrument, repeating the same population’s testing with the same instrument would aid in verifying its stability and reliability. |

| Xinran et al. [44] | information’s perceived characteristics and socializing | Compared to men (n = 73, 42.7%), women (n = 98) made up 57.3%. | Self-expression and socialization, along with the information’s perceived qualities, were the main justifications. | The sample that was produced is not typical of all college students. |

Additionally, we looked at psychological aspects such as biological processes (e.g., eat, pain, love, emotion), social processes (e.g., family and friends), cognitive processes (e.g., think, cause, thoughts, attitudes, belief), and personal concerns (e.g., work, leisure, achieve, home, money, religion, death, motivations, intention). The study of the data showed that the variables most frequently researched were those that the current review classified as “personal factors” in relation to the elements linked to creation and distributing fake news, while social effects were the variables that were studied the least. Emotional aspects have also been covered in numerous studies. Subsequently, the evaluation process yielded factors linked to the creation and dissemination of fake news, which were then classified into four groups: (a) individual characteristics; (b) cognition; (c) affection; and (d) societal processes. The psychological elements are categorized based on their domain in Table 4.

Table 4.

Psychological factors domain

| Psychological Factors | Subdomain |

|---|---|

| (A) Individual Characteristics | Altruism, motivation, moral consciousness, personality, fear of missing out, social media fatigue, role of conscientiousness |

| (B) Cognition | Attitudes and belief |

| (C) Affection | Emotion |

| (D) Social Processes | Socialization, social media literacy, entertainment |

Findings and discussion

Individual characteristics

Few studies show evidence that altruism contributes to sharing fake news among social media users [17–19, 39]. The driving force behind altruism is the desire to better the welfare of another person to better one’s own well-being. Altruism and associated concepts such as collaboration and reciprocity are commonly regarded as uniquely human characteristics [45]. Besides that, altruism influences the decision to disseminate fake news on social media platforms [46]. Previous studies have also discovered that social media information dissemination is influenced by benevolence [47]. This indicates that a selfless person finds satisfaction in helping others. However, we argue that people may contribute to the propagation of false information if they do not pay closer attention to what is being shared. In a study done by Apuke and Omar [18], it has been shown that altruism is a distinct trait of the average Nigerian, and it is more of a cultural characteristic [18]. Motivation is another psychological factor, which helps in the dissemination of fake news (17–18, 26, 32, 36–37). Motivation is defined as the energy that drives someone to complete a goal. Motivation is frequently motivated by some rationale where it makes sense in the context of the individual [48].

The motive behind disseminating fake news is also linked to elements including social media weariness, self-promotion, internet confidence, self-reporting, and fear of missing out [17, 36]. Self-promotion drive is a type of motivation that appears when users want to show other users that they are highly competent or that they are intelligent or skilled [18, 49]. While promoting oneself is linked to projecting a positive image to others, this could discourage people from spreading false information [36]. Furthermore, studies have shown that those who spread false information out of a fear of missing out are more inclined to do so [36]. These findings go counter to the theory that exclusion anxiety, one of the factors influencing fear of missing out, causes a decline in self-regulation and an increase in undesirable behaviour [50]. This implies that people may share fake news online because of a need to use social media in spite of fatigue, as it can be an easy way to keep engaged without putting in a lot of work. Moreover, they might unknowingly disseminate false information. This result is in line with the findings of Logan et al., who contended that users experiencing social media fatigue make more mistakes and get confused [51]. Additionally, the sociotechnical model of media effects predicts that tired users will disseminate false information.

In terms of creation fake news, Shehata and Eldakar [32] had discovered that motivation demonstrated that individuals create false material on social media for a variety of reasons, while obtaining pertinent information and lowering anxiety were the primary drivers. The study’s findings suggested that although some social media users may create false information for other purposes, such as amusement, forming and strengthening friendships, or engaging with friends, the majority of users did so to obtain pertinent updates and feel less anxious [32]. Recent scholarly research has emphasised the various modern aspects that impact the production of fake news. The influence of social media platforms is one important component. Research has demonstrated that these platforms’ algorithm-driven content promotion helps spread disinformation quickly [52]. Furthermore, “echo chambers” on social media are a phenomenon that aids in the dissemination of fake news since people are more likely to come across and accept content that confirms their preconceived notions [53]. Fake news is also created and for the need for social approval and the attraction of sensational information [54]. These results highlight the intricate interactions of social, technological, and psychological elements in the creation of fake news.

Personality [25, 34, 38, 41]. Psychology uses personality to categorize several individual characteristics that affect behaviour [55]. All of them used the Big Five personality model to explain the personality characteristics of sharing fake news [21, 30, 34, 37] exhibiting traits of big five personality which are Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. The qualities of this five trait or dimension are derived from research into how people identify themselves and one another in normal or everyday language [55]. From these findings, we found that the individuals who disseminate fake news have high levels of Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism. While extraversion and agreeableness traits are consistent with previous research on the relationship between social media engagement and personality [56, 57]. The background of the COVID-19 epidemic, which sends messages of dread, loneliness, melancholy, anger, uncertainty, and grief, among other things, may help to explain why neuroticism initially seems odder. The information source and agreeableness attribute may interact, with more pleasant people being more driven to please those who are important to them. The stories might be important, and misinformation products are usually adversarial or critical in character. This may suggest that they are more likely to be shared by irascible individuals who don’t care to apologize to others or take offence at them. Moreover, agreeableness and general trusting behaviour are related. It may be that individuals who are unpleasant are more likely to read conspiratorial literature or other materials that are consistent with a lack of faith in public figures such as politicians.

However, a study done by Lawson and Kakkar [34], only explored the role of conscientiousness against fake news sharing behaviour. Besides that, individuals with lower conscientiousness are more inclined to share fake news, which is not surprising as they are less likely to verify the authenticity of a story before sharing it. This viewpoint is reinforced by the absence of a link with deliberate historical sharing. In addition, an individual’s moral consciousness [27] is referred to as thoughts about moral principles that vary according to the stage of moral development. Moral consciousness represents a deeply entrenched and pervasive conception of everyday life, unlike moral reasoning or judgement, which occurs in response to moral quandaries posed during measurement. From the findings, ideologically motivated political brand hatred is motivated by a desire to maintain one’s moral conscience, which amplifies the consequence of hatred by propagating bogus news.

Cognition

One study explored attitudes and beliefs as one of the psychological factors [41]. According to Bryanov and Vziatysheva [58], attitudes and beliefs relate to people’s perceptions and assessments of themselves and other people [58]. In this study, attitudes and belief factors contributing to the sharing of fake news among social media users are explored. The scientific study of cognition is the process by which a person uses reasoning to make sense of particular subjects or data, and comprehension is the process by which a person interprets ideas and reasoning correctly [12]. With so much content available on social media, users could find it difficult to decide which information is closest to the original source. This may have an impact on their attitudes and beliefs towards sharing certain information they have come across on social media [12]. The problem of people being unable to distinguish between real and fake news has been highlighted by numerous publications. There is a lower likelihood that social media users will research the content they read or post. Any unconfirmed content can therefore be swiftly shared and distributed over social media platforms [59].

Ignorance

Social media users’ mindless forwarding of erroneous information is one of the main factors contributing to the spread of inaccurate information [60]. The spread of false information is frequently the result of careless people who are unaware that certain websites imitate real websites [59]. These phony websites are designed to resemble the authentic ones, yet their content is entirely fabricated. Without verifying the facts and sources, social media users are more inclined to spread content with an attention-grabbing headline [61]. False information spreads because users don’t check the content on social media sites. Social media users frequently distribute content without checking its accuracy or source [59].

Affection

Emotion is also one of the psychological factors to be studied for its influence on fake news dissemination [30, 33, 40]. Different emotions have been proposed to influence judgement in general and perceptions of fake news sharing. This study has shown how emotions and personal attitudes interact to make people believe fake news more and feel more motivated to spread it online for self-expression [62]. Ali et al. [30] studied anger and fear, while Anu and Fransesca [34] explored different types of emotions such as rage, happiness, despair, contempt, fear, surprise, anticipation, and trust. Chuai & Zhao explored anger emotion with sharing fake news [40]. Emotions such as anger, fear, sadness, and anxiety make social media users share bogus news for amusement or enjoyment [49]. Emotion influences the user’s proclivity to interpret bogus news as true (16, 63–64). This suggests that the tendency of social media users to perceive news based on their emotions leads to them believing and sharing fake news with others [16].

Social processes

Socialization plays a key role in spreading false information. The frequency of social connection between people is the most important factor in determining socialization pleasure. The pleasure of socializing was investigated in relation to the desire to create social capital and contrast it with others while sharing news on social media (18–19, 39). Social media literacy is also another psychological factor that affects fake news sharing [28]. According to Schreurs and Vandenbosch, the technical and mental skills required for users to use social media effectively and efficiently for online communication and social participation are known as social media literacy skills [65]. In addition, entertainment is another factor, which contributes to fake news sharing. Entertainment is defined as the use of social media sites to simply eliminate boredom [17]. According to Chuai and Zhao, one of the most important motives for using social media is recognition and the fulfilment of time passes is intimately tied to the dissemination of false news [40]. Furthermore, disseminating fake news for the sake of entertainment when someone else is duped by it, or just because it’s an exciting experience. These people, who might know better, might tell others who are less wary about this “funny” news to provide them with a quick thrill.

Social media platforms are being used to spread fake news to mislead the public for political ends [12]. Numerous papers have asserted that people who use social media are more likely to look for information from people who hold similar opinions to them [12, 66]. An individual must socialize to modify their behaviour to fit within a certain social group [67]. Users of social media may submit facts to gain social acceptance and enhance their image out of a desire to better themselves, making it difficult for them to distinguish between accurate and false information [36]. Research indicates that messages pertaining to particular people or influencers on social media platforms like Twitter are amplified [68]. The ratings of significant users connected to the information determine the flow of information [60].

The effect and dissemination of many types of information are enhanced by social media users’ influence on their peers [68]. The information’s impact may be amplified by these influencers’ degree of power [69]. People may share information based on the thoughts and deeds of others because there is a dearth of pertinent material in online forums [60]. Certain studies indicate that people on social media will look for or spread information that supports their beliefs or worldviews [70]. One essential aspect of using social media is social media literacy, which is the capacity of users to distinguish between what is real and what is fake [71]. People are more likely to share information on social media when the contact is successful [36]. Social media users provide seemingly reasonable arguments to confirm the veracity of the content being offered [72]. Some people’s lack of intelligence is used by those who post inaccurate content and produce fake news websites [73]. Expert content judgement is required for social media users to determine if the material they get is authentic or incorrect [74].

This research contributes to the Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by providing insights into the psychological and motivational drivers behind the creation and dissemination of fake news on social media. UGT, which posits that individuals actively seek media to fulfil specific needs such as information, social interaction, and identity reinforcement, can explain how users engage with fake news to gratify personal or social desires like gaining social approval or validating pre-existing beliefs. In parallel, SDT, which emphasizes the role of intrinsic motivation such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness which helps to explain how individuals might create or spread fake news as a way to assert control (autonomy), demonstrate knowledge (competence), or foster social connections (relatedness). Through these lenses, this research sheds light on the complex interplay of personal, social, and psychological factors that drive fake news behaviour, thus extending the theoretical understanding of media consumption and interaction in digital environments.

The Uses and Gratifications theory [75] is a well-liked theory that is frequently used to investigate social media gratifications. It postulates that people utilise technologies to satisfy their psychological and social needs. The theory focuses on what individuals do with media instead of what media does to them and was applied as an extension of requirements and motivation theory, despite its initial design and application to comprehend the factors influencing users’ choice of media [76]. The Uses and Gratifications theory can be broadly classified into four categories which are social, process, content, and technology. Self Determination Theory evaluates human motivation and personality and asserts that people have basic psychological needs to be met, such as relatedness, autonomy, and competence [77]. Individuals grow, feel good, and maintain their integrity when these basic needs are met. Self Determination Theory contributes to the explanation of how the need for relatedness and a sense of belonging drives the millennial generation’s version of fear of missing out. It also involves the fear of losing out on enjoyable and fulfilling experiences [78]. There is evidence that connects fear of missing out to unhealthy habits such as excessive Internet use [79, 80] and dissemination of fake news [36].

Theoretical and practical implications

The findings of this systematic review contribute to the development of a more comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding the psychological factors involved in the creation and dissemination of fake news on social media. By integrating cognitive, emotional, and social identity theories, this review extends existing research beyond isolated psychological processes to illustrate how these factors interact in complex ways. For instance, cognitive biases such as confirmation bias and the illusory truth effect, previously studied in isolation, are shown to work in tandem with emotional triggers and social identity-driven motivations to shape user behaviour. The review also has implications for social identity theory [81] which explains how individuals’ identification with particular social or political groups influences their information-sharing behaviour.

Weeks & Gil de Zúñiga [82] show that partisanship and group loyalty can increase the likelihood of sharing misinformation that aligns with one’s social identity, even when it is false. The review integrates these insights with social psychology theories of group polarization [83] suggesting that in-group dynamics and the need for social approval play key roles in the propagation of fake news. This more holistic approach highlights the importance of considering multi-level influences, advancing theories of media psychology, misinformation, and social identity in digital contexts. Additionally, by advancing these theoretical insights, this review encourages future research to adopt interdisciplinary approaches that incorporate psychological, communication, and sociological perspectives, thus filling gaps in existing theoretical models on the psychological underpinnings of fake news dissemination.

In addition, by incorporating Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) into this review highlights the psychological motivations behind fake news creation and dissemination, emphasizing that these behaviours are often rooted in deeper psychological needs for gratification, autonomy, and social belonging. This offers a more nuanced understanding of fake news engagement, suggesting that interventions should not only focus on debunking false information but also address the underlying psychological drivers that compel individuals to create and share misinformation. These theories also encourage future research to explore how satisfying these psychological needs might lead to a preference for emotionally charged, biased, or sensational content, further contributing to the persistence and spread of fake news.

From a practical standpoint, the insights from this review can inform strategies for mitigating the spread of fake news on social media. For social media platforms and policymakers, understanding the psychological drivers of misinformation dissemination can guide the design of more effective interventions, such as content moderation tools, educational campaigns, and user prompts that target specific cognitive biases or emotional responses. For example, increasing users’ awareness of cognitive biases could lead to more critical engagement with content, while strategies aimed at reducing emotional contagion, such as flagging highly emotive posts, may curb rapid misinformation sharing. Additionally, this review’s findings can help media literacy programs focus on building resilience against the psychological triggers that make users vulnerable to fake news, thereby empowering individuals to make more informed decisions online. Finally, insights into social identity dynamics can be used to develop community-based interventions that address group-based misinformation sharing, fostering healthier online environments.

Limitation and future studies

The conclusions drawn from the findings of this systematic study should be evaluated in light of the numerous limitations. Firstly, the 23 examined research used different types of research design. As a result, there is a possibility of bias in our perception, magnitude of impacts, and research lacks consistency. Furthermore, this review explored various types of psychological factors, alongside other significant construct, which can heavily influence the dissemination of fake news. Future reviews should consider focusing on a single psychological factor for emphasis. The main source of secondary data for our analysis is academic literature on misleading news. There aren’t many sources for the grey literature, despite our best efforts to incorporate it in our review. Future studies can therefore build on this work and produce a deeper understanding of the topic at hand. Besides that, to meet our research goals and provide support for our critical review effort, we have used significant databases and meaningful keywords to find pertinent papers.

We present our work as wholly unique, comprehensive, and important in nature given our keyword strategy. It serves as a launchpad for more study aimed at delving deeper into the rapidly developing field of fake news. Besides that, this review aims to focus on psychological factors in general. Future research should focus on just one factors to gain more insights on how the factors affects dissemination of fake news. Future studies should collect data on other potential factors or essential characteristics and their interactions in predicting the dissemination and creation of fake news, which would aid in developing a more specific profile in reducing this issue. Although this study focuses on creation and dissemination of fake news, but the research only able to include one study from creation of fake news where in future research equal number of studies should be included or the review should only focus on either creation or dissemination for a more comprehensive finding.

Besides that, future studies could investigate how specific psychological factors, such as cognitive dissonance, emotional contagion, or social identity theory, influence not only the reception but also the active creation of misinformation. Additionally, research could delve into how psychological characteristics differ across populations or cultural contexts in shaping susceptibility to fake news. There is also a need to explore the psychological impact of repeated exposure to misinformation on behaviour and belief systems, as well as how interventions targeting these factors might mitigate the spread of fake news. Lastly, interdisciplinary research combining psychological insights with technological solutions could offer a more holistic approach to addressing the issue. By suggesting these avenues for future inquiry, the authors would significantly contribute to advancing both the theoretical and practical understanding of the psychological dimensions driving the creation and dissemination of fake news.

Conclusion

Researchers concur that due to substantial personal and community costs, it should become a new public health priority on the impact of disseminating and creating fake news. This comprehensive review found that different types of psychological factors may play a significant effect in the dissemination and creation of fake news. Lastly, this review educates individuals on the significance of false information. Specifically, it will help individuals comprehend the effects that false information on social media can have on their lives. Furthermore, this research will assist policymakers in creating strategies to combat false news by offering a more comprehensive knowledge of the phenomena. The results of this study could help anyone making decisions during a serious emergency. It may be more successful to concentrate on the psychological factors rather than the emotional component of information control when attempting to curb the dissemination of rumours, particularly those that have the potential to significantly alter people’s actions. To put it another way, changing people’s attitudes and beliefs regarding rumours may prove to be far more significant than emphasising the feelings of individuals who hear about rumours and may end up distributing them to a large number of people.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the researchers whose articles were used in the present research.

Author contributions

S.M. and A.A.H.S. did the conceptualization, framework, literature search and screening of the literature under the supervision of M.R.K. and R.J. Besides that, K.S. and M.A.P. reviewed the paper.

Funding

This review is based on the research supported by the Universitas Padjadjaran grant [Grant number: 1465/UN6.I/TU.00/2023] / SK-2023-017].

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Rahim Kamaluddin, Email: rahimk@ukm.edu.my.

Ratna Jatnika, Email: ratna@unpad.ac.id.

References

- 1.Shin J, Jian L, Driscoll K, Bar F. The diffusion of misinformation on social media: temporal pattern, message, and source. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;83:278–87. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo L, Zhang Y. Information flow within and across online media platforms: an agenda-setting analysis of rumor diffusion on news websites, Weibo, and WeChat in China. Journalism Stud. 2020;21(15):2176–95. 10.1080/1461670X.2020.1827012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazer DM, Baum MA, Benkler Y, Berinsky AJ, Greenhill KM, Menczer F, Metzger MJ, Nyhan B, Pennycook G, Rothschild D, Schudson M. The science of fake news. Science. 2018;359(6380):1094–6. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruchansky N, Seo S, Liu Y, Csi. A hybrid deep model for fake news detection. InProceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management 2017 (pp. 797–806). 10.1145/3132847.3132877

- 5.Pennycook G, Rand DG. The Implied Truth Effect: attaching warnings to a subset of fake news stories increases perceived accuracy of stories without warnings. Manage Sci. 2018;66(11):4944–57. 10.1287/mnsc.2019.3478. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH, Cook J. Beyond misinformation: understanding and coping with the Post-truth era. J Appl Res Memory Cognition. 2017;6(4):353–69. 10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faustini PH, Covoes TF. Fake news detection in multiple platforms and languages. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;158:113503. 10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113503. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang YF, Chen PH. Fake news detection using an ensemble learning model based on self-adaptive harmony search algorithms. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;159:113584. 10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113584. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin J, Thorson K. Partisan selective sharing: the biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. J Commun. 2017;67:233–55. 10.1111/jcom.12284. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang SM, Geng T, Queenie Li J-Y, Xia R, Huang C-T, Kim H, et al. A computational approach for examining the roots and spreading patterns of fake news: evolution tree analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;84:103–13. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.032. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrew S, Breakstone J, Ortega T, Smith M, Wineburg S. Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theor Res Soc Educ. 2018;46:165–93. 10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weeks BE. Emotions, partisanship, and misperceptions: how anger and anxiety moderate the effect of partisan bias on susceptibility to political misinformation. J Communication. 2015;65(4):699–719. 10.1111/jcom.12164. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas K, Nilsson E, Festin K, Henriksson P, Lowén M, Löf M, Kristenson M. Associations of psychosocial factors with multiple health behaviors: a population-based study of middle-aged men and women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1239. 10.3390/ijerph17041239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha YM, de Moura GA, Desidério GA, de Oliveira CH, Lourenço FD, de Figueiredo Nicolete LD. The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Public Health 2021 Oct 9:1–0. 10.1007/s10389-021-01658-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Friggeri A, Adamic LA, Eckles D, Cheng J. (2014). Rumor Cascades. Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM), 101–110. Retrieved from https://www.aaai.org

- 16.Martel C, Pennycook G, Rand DG. Reliance on emotion promotes belief in fake news. Cogn Research: Principles Implications. 2020;5:1–20. 10.1186/s41235-020-00252-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balakrishnan V, Ng KS, Rahim HA. To share or not to share–the underlying motives of sharing fake news amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. Technol Soc. 2021;66:101676. 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apuke OD, Omar B. Fake news and COVID-19: modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telematics Inform. 2021;56:101475. 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omar B, Apuke OD, Nor ZM. The intrinsic and extrinsic factors predicting fake news sharing among social media users: the moderating role of fake news awareness. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(2):1235–47. 10.1007/s12144-023-04343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moravec PL, Minas RA, Dennis AR. Fake news on social media: people believe what they want to believe when it makes no sense at all. MIS Q. 2019;43(4):1343–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bode L, Vraga EK. See something, say something: correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health Commun. 2018;33(9):1131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oeldorf-Hirsch A, Sundar SS. Posting, commenting, and tagging: effects of sharing news stories on Facebook. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;44:240–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan A, Brohman K, Addas S. The anatomy of ‘fake news’: studying false messages as digital objects. J Inform Technol. 2022;37(2):122–43. 10.1177/02683962211037693. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Buchanan T. Why do people spread false information online? The effects of message and viewer characteristics on self-reported likelihood of sharing social media disinformation. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0239666. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrigo P, Arakpogun EO, Vu MC, Olan F, Djafarova E. Can you be mindful? The effectiveness of mindfulness-driven interventions in enhancing the digital resilience to fake news on COVID-19. Inform Syst Front 2022 Mar 2:1–21. 10.1007/s10796-022-10258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Sharma I, Jain K, Behl A, Baabdullah A, Giannakis M, Dwivedi Y. Examining the motivations of sharing political deepfake videos: the role of political brand hate and moral consciousness. Internet Res. 2023;33(5):1727–49. 10.1108/INTR-07-2022-0563. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei L, Gong J, Xu J, Abidin NE, Apuke OD. Do social media literacy skills help in combating fake news spread? Modelling the moderating role of social media literacy skills in the relationship between rational choice factors and fake news sharing behaviour. Telematics Inform. 2023;76:101910. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apuke OD, Omar B. Modelling the antecedent factors that affect online fake news sharing on COVID-19: the moderating role of fake news knowledge. Health Educ Res. 2020;35(5):490–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali K, Li C, Muqtadir SA. The effects of emotions, individual attitudes towards vaccination, and social endorsements on perceived fake news credibility and sharing motivations. Comput Hum Behav. 2022;134:107307. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stefanone MA, Vollmer M, Covert JM. In news we trust? Examining credibility and sharing behaviors of fake news. InProceedings of the 10th international conference on social media and society 2019 Jul 19 (pp. 136–147). 10.1145/3328529.3328554

- 32.Shehata A, Eldakar M. An exploration of Egyptian Facebook users’ perceptions and behavior of COVID-19 misinformation. Sci Technol Libr. 2021;40(4):390–415. 10.1080/0194262X.2021.1925203. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shrestha A, Spezzano F (2021) An analysis of people’s reasoning for sharing real and fake news. Boise State University.

- 34.Lawson MA, Kakkar H. Of pandemics, politics, and personality: the role of conscientiousness and political ideology in the sharing of fake news. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2022;151(5):1154. 10.1037/xge0001120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobato EJ, Powell M, Padilla LM, Holbrook C. Factors predicting willingness to share COVID-19 misinformation. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566108. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talwar S, Dhir A, Kaur P, Zafar N, Alrasheedy M. Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. J Retail Consum Serv. 2019;51:72–82. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.026. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar A, Shankar A, Behl A, Arya V, Gupta N. Should I share it? Factors influencing fake news-sharing behaviour: a behavioural reasoning theory perspective. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2023;193:122647. 10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122647. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nurbakova D, Ermakova L, Ovchinnikova I. Understanding the Personality of Contributors to Information Cascades in Social Media in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. In2020 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW) 2020 Nov 17 (pp. 45–52). IEEE.

- 39.Thanh NN, Tung PH, Thu NH, Kien PD, Nguyet NA. Factors affecting the share of fake news about covid-19 outbreak on social networks in Vietnam. J Lib Int Affairs. 2021;7(3):179–95. 10.47305/JLIA2137179t. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chuai Y, Zhao J. Anger can make fake news viral online. Front Phys. 2022;10:970174. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li K, Li J, Zhou F. The effects of personality traits on online rumor sharing: the mediating role of fear of COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:6157. 10.3390/ijerph19106157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weimann-Saks D, Elshar-Malka V, Ariel Y, Weimann G. Spreading online rumours during the Covid-19 pandemic: the role of users’ knowledge, trust and emotions as predictors of the spreading patterns. J Int Communication. 2022;28(2):249–64. 10.1080/13216597.2022.2099443. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han J, Cha M, Lee W. Emotion and misinformation in times of public health crisis. Harv Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Rev. 2020;1(3).

- 44.Chen X, Sin SC, Theng YL, Lee CS. Why students share misinformation on social media: motivation, gender, and study-level differences. J Acad Librariansh. 2015;41(5):583–92. 10.1016/j.acalib.2015.07.003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. The nature of human altruism. Nature. 2003;425(6960):785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plume CJ, Slade EL. Sharing of Sponsored Advertisements on Social Media: a uses and gratifications perspective. Inform Syst Front. 2018;20(3):471–83. 10.1007/s10796-017-9821-8. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma WWK, Chan A. Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;39:51–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. 10.1007/s10964-007-9178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Islam AN, Laato S, Talukder S, Sutinen E. Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: an affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2020;159:120201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Twenge JM. Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2005;88(4):589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Logan K, Bright LF, Grau SL. Unfriend me, please! Social media fatigue and the theory of rational choice. J Mark Theory Pract. 2018;26(4):357–67. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S. The spread of true and false news online. Science. 2018;359(6380):1146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cinelli M, Morales GDF, Galeazzi A, Quattrociocchi W, Starnini M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9), e2023301118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Pennycook G, Rand DG. The Implied Truth Effect: attaching warnings to a subset of fake news stories increases perceived accuracy of stories without warnings. Manage Sci. 2019;66(11):4944–57. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Costa PT, McCrae RR. A five-factor theory of personality. The five-factor model of personality. Theoretical Perspect. 1999;2:51–87. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee K, Mahmud J, Chen J, Zhou M, Nichols J. Who will retweet this? automatically identifying and engaging strangers on twitter to spread information. InProceedings of the 19th international conference on Intelligent User Interfaces 2014 Feb 24 (pp. 247–256). 10.1145/2557500.2557502

- 57.Mahmud J, Zhou M, Megiddo N, Nichols J, Drews C. Optimizing the selection of strangers to answer questions in social media. arXiv preprint arXiv:1404.2013. 2014 Apr 8.

- 58.Bryanov K, Vziatysheva V. Determinants of individuals’ belief in fake news: a scoping review determinants of belief in fake news. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0253717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bondielli A, Marcelloni F. A survey on fake news and rumour detection techniques. Inf Sci. 2019;497:38–55. 10.1016/j.ins.2019.05.035. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Q, Yang X, Xi W. Effects of group arguments on rumor belief and transmission in online communities: an information cascade and group polarization perspective. Inf Manag. 2018;55(4):441–9. 10.1016/j.im.2017.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rochlin N. Fake news: belief in post-truth. Libr Hi Tech. 2017;35(3):386–92. doi: 0.1108/LHT-03-2017-0062. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weeks BE. Emotions, partisanship, and misperceptions: how anger and anxiety moderate the effect of partisan bias on susceptibility to political misinformation. J Communication. 2015;65(4):699–719. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Germani F, Biller-Andorno N. The anti-vaccination infodemic on social media: a behavioral analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0247642. 10.1371/journal.pone.0247642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 64.Sudhir S, Unnithan AB. Marketplace rumor sharing among young consumers: the role of anxiety and arousal. Young Consumers. 2019;20(1):1–3. 10.1108/YC-05-2018-00809. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schreurs L, Vandenbosch L. Introducing the Social Media Literacy (SMILE) model with the case of the positivity bias on social media. J Child Media. 2021;15(3):320–37. 10.1080/17482798.2020.1809481. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buschman J. Good news, bad news, and fake news: going beyond political literacy to democracy and libraries. J Doc. 2019;75(1):213–28. 10.1108/JD-05-2018-0074. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colliander J. This is fake news’: investigating the role of conformity to other users’ views when commenting on and spreading disinformation in social media. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;97:202–15. 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.032. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vijaykumar S, Nowak G, Himelboim I, Jin Y. Virtual Zika transmission after the first U.S. case: who said what and how it spread on Twitter. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(5):549–57. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borges-Tiago MT, Tiago F, Cosme C. Exploring users’ motivations to participate in viral communication on social media. J Bus Res. 2018;101:574–82. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.011. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lor PJ. Democracy, information, and libraries in a time of post-truth discourse. Libr Manag. 2018;39(5):307–21. 10.1108/LM-06-2017-0061. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Figueira Á, Oliveira L. The current state of fake news: challenges and opportunities. Proc Comput Sci. 2017;121:817–25. 10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.106. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park K, Rim H. Social media hoaxes, political ideology, and the role of issue confidence. Telematics Inf. 2019;36:1–11. 10.1016/j.tele.2018.11.001. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burkhardt JM. History of fake news. Libr Technol Rep. 2017;53(8):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Obelitz Søe S. Algorithmic detection of misinformation and disinformation: gricean perspectives. J Doc. 2018;72(2):309. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blumler JG, Katz E. The uses of Mass communications: current perspectives on Gratifications Research. Beverly Hills, California: Sage; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katz E, Blumler JG, Gurevitch M. Uses and gratification research. Publ Opin Q. 1973;37:509–23. 10.1086/268109. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Przybylski AK, Murayama K, DeHaan CR, Gladwell V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29:1841–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014. [Google Scholar]

- 79.King DL, Delfabbro PH. The cognitive psychopathology of internet gaming disorder in adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44:1635–45. 10.1007/s10802-016-0135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dempsey AE, O’Brien KD, Tiamiyu MF, Elhai JD. Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use. Addict Behav Rep. 2019;9:100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. abrep.2018.100150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weeks BE, de Gil H. The role of social media in political participation: a social identity perspective. New Media Soc. 2019;21(6):1362–83. 10.1177/1461444818780971. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sunstein CR. Republic.com. Princeton University Press; 2002.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.