Abstract

Objectives

We elucidate the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on assisted reproductive technology (ART) services and birth outcomes and establish an evidence-based framework to maintain the high quality of ART healthcare services and ensure continuous improvement of birth outcomes.

Methods

A total of 19,170 pregnant women from Sichuan, Guizhou and Chongqing in Southwest China between 2018 and 2021 were included in this study. The log-binomial regression model was employed to analyse the changes in the probability of adverse birth outcomes, such as low birth weight (LBW), preterm birth (PTB), Apgar score < 7 at 1 min and congenital anomalies (CAs) and their relationship with ART before and after the pandemic. In this analysis, confounding factors such as family annual income, maternal ethnicity, delivery age, subjective prenatal health status, vitamin or mineral supplementation during pregnancy and level of prenatal care provided by the hospital were controlled.

Results

ART mothers had the highest probability of giving birth to LBW babies (relative risk (RR): 2.82, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.32–3.41), experiencing PTB (RR: 2.72, 95% CI: 2.78–3.22) and delivering babies with an Apgar score < 7 at 1 min (RR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.05–2.69). Before the pandemic, the ART rate increased from 4.42% in 2018 to 6.71% in 2019 (rate difference of 2.29%, P < 0.001). After the pandemic, the ART rate decreased from 6.71% in 2019 to 6.55% in 2020 (rate difference of − 0.16%, P = 0.752). Compared with the pre-pandemic period, the rate difference for LBW decreased from − 0.21% (P = 0.646) in 2018–2019 to an increase of + 0.89% (P = 0.030) in 2019–2020. Similarly, PTB showed an increase in rate difference from + 0.20% (P = 0.623) before the pandemic to + 0.53% (P = 0.256) afterwards. Apgar score < 7 at 1 min had a negative rate difference of − 0.50% (P = 0.012), which changed to a positive value of + 0.20% (P = 0.340). For CAs, the rate difference increased from + 0.34% (P = 0.089) prior to the outbreak to + 0.59% (P = 0.102) at post-outbreak. In 2018 (pre-pandemic), ART was the most significant predictor of LBW, exhibiting an RR of 3.45 (95% CI: 2.57–4.53). Furthermore, in 2020, its RR was 2.49 (95% CI: 1.78–3.42). Prior to the onset of the pandemic (2018), ART (RR: 3.17, 95% CI: 2.42–4.08) was the most robust predictor of PTB. In 2020, its RR was 2.23 (95% CI: 1.65–2.97).

Conclusion

ART services have been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the resulting delays in ART services have had notable implications for maternal birth outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-024-06935-9.

Keywords: COVID-19, PTB, LBW, CA, Apgar

Background

What is known

The application of ART is increasing in China and abroad

Since the world’s first test-tube baby appeared in 1978, assisted reproductive technology (ART) has been rapidly promoted worldwide. At present, more than 8 million ART pregnancies have been achieved globally, and the proportion of ART neonates in different regions or countries continues to increase. From 2016 to 2018, the proportion of ART neonates increased from 2.9% to 3.5% in Europe and from 1.8% to 2.0% in the United States. According to official reports, the annual total number of ART treatments in China has exceeded 450,000, which is lower than the 1 million in the European Union, close to that in Japan, approximately 1.5 times that in the United States, about 4.4 times that in Latin America and approximately 5.4 times that in Australia and New Zealand [1].

ART users have a high risk of adverse birth outcomes

ART encompasses various techniques, including in vitro fertilisation, intracytoplasmic sperm injection and frozen embryo [2]. Studies utilising extensive datasets from the United Kingdom, Finland, China and other regions suggested that ART itself does not augment the risk of adverse birth outcomes, such as low birth weight (LBW) or preterm birth (PTB) [3–5]. Nevertheless, existing evidence indicates that individuals utilising ART face an elevated risk of adverse birth outcomes compared with those undergoing natural pregnancies. This disparity may be attributed to diminished fertility due to advanced maternal age and the high likelihood of multiple gestations among ART users [3].

COVID-19 infection does not impact art success rate

Although men with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may carry the virus in their sperm [6], no significant disparity in reproductive capacity has been observed between those infected and those not infected [7]. Moreover, a number of patients with a history of COVID-19 (317 patients) exhibited no statistically significant divergence in artificial insemination outcomes compared with those without such history [8]. A study in China also found no variation in the success rate of ART pregnancies or miscarriage rates during the peak and post-control periods of the COVID-19 pandemic [9].

Reduction in ART services during the pandemic

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, certain countries or regions temporarily halted their ART services in accordance with local government mandates, recommendations or suggestions [10, 11]. A nationwide survey conducted in China also revealed a significant decline of 45% in outpatient and service volumes at reproductive centres’ sperm banks during the first four months of 2020 compared with those during the same period in 2019 [12]. With previous research indicating the increased vulnerability of pregnant women to COVID-19 compared with other populations [13], concerns about contracting the virus within hospital settings led to a decrease in the active seeking of ART services among this demographic during the pandemic [14].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on regional disparities in adverse birth outcomes

A study involving 438,548 pregnant women suggested that compared with uninfected women, pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 have an increased risk of experiencing PTB, LBW and stillbirth to varying degrees [15]. Collectively, evidence indicates a significant increase in certain adverse birth outcomes, such as stillbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, a decrease in PTBs was observed in high-income countries such as the United States, the Netherlands and Japan [16–18]. Conversely, mid- or low-income countries, including Nepal [19], Turkey [20] and India [21], have experienced a significant rise in stillbirth rates due to the relatively inadequate healthcare services and limited capacity to respond effectively to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on foetal health may have enduring intergenerational effects and exacerbate social demographic disparities in birth outcomes [22].

What are the problems

As a lower- to middle-income country, China was severely affected during the pandemic. Different from most Western countries that ended their control measures in mid-2020, China’s lockdown policy lasted until 2022, when the control measures were gradually lifted. This prolonged lockdown raises questions about how the pandemic has influenced the proportion of ART usage, the incidence of adverse birth outcomes and the probability of adverse birth outcomes among ART users. However, this matter has not been clarified due to incomplete ART-related data sets and complication records [12].

Existing studies in China primarily relied on case–control studies comparing infected and non-infected pregnant women and rare birth cohort studies [23], which may not be as efficient. Longitudinal birth cohort studies spanning pre- and post-pandemic periods are even scarcer but offer an excellent design for investigating the impact of the pandemic.

The problems this study aims to solve

This study aims to demonstrate the inherent trajectory of birth outcomes before the pandemic and the subsequent changes during the pandemic to mitigate the confusion associated with natural trends and provide a precise assessment of the pandemic’s impact.

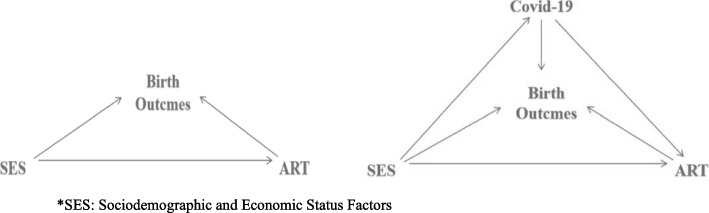

Another objective of this study is to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ART services, birth outcomes and their correlation (Fig. 1) and to identify priority intervention strategies by exploring potential causes.

Fig. 1.

Association between assisted reproductive technology and birth outcomes before (left) and during (right) the pandemic. *SES: Sociodemographic and Economic Status Factors

Potential significance or value of this study

This study can serve as a valuable reference for individuals infected with COVID-19 deciding whether to receive ART or not. We elucidate the impact of the pandemic on ART services and birth outcomes to establish an evidence-based framework for maintaining the high quality of ART healthcare services and ensuring continuous improvement in birth outcomes. Most importantly, this work offers valuable Chinese evidence for effectively addressing changes in ART services and birth outcomes during unknown infectious disease outbreaks in the future.

Methods

Study design

We selected 17 maternity hospitals in Sichuan, Chongqing and Guizhou provinces, including 3 provincial, 5 municipal and 9 district-level institutions as the research sites. A total of 20,730 singleton pregnant women who came to the hospital for antenatal care in their first trimester and agreed to participate in our cohort were investigated by trained medical staff. Exclusion criteria were pregnant women with psychosis or under 18 years of age.

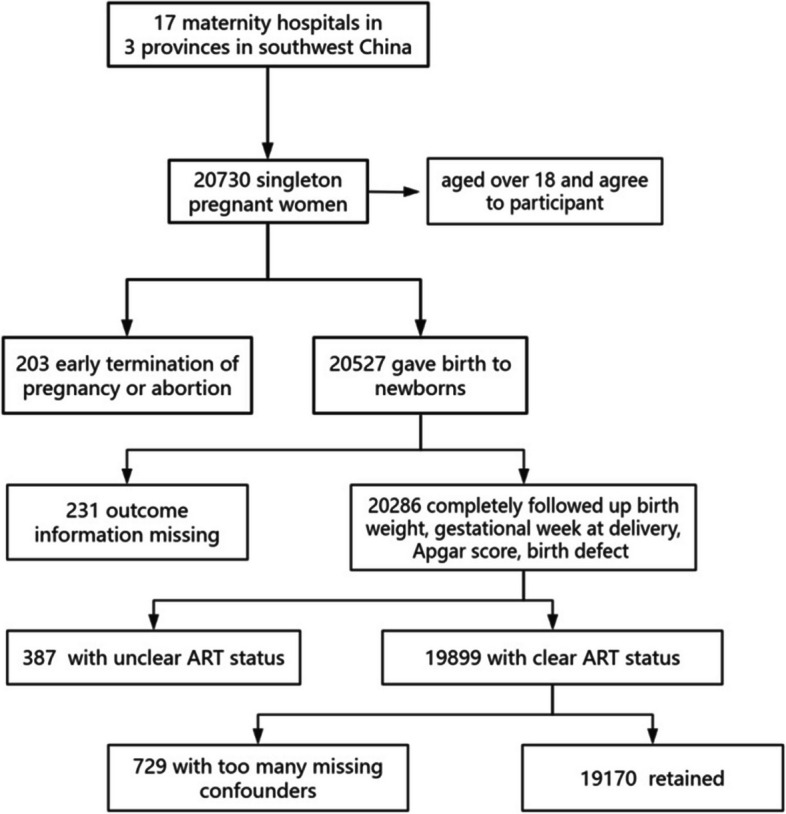

A total of 20,527 mothers gave birth to newborns, and 20,286 of them received newborn birth weighing, Apgar scoring, birth defect screening and diagnosis. After 387 pregnant women with unclear ART status were excluded, 19,899 pregnant women were retained. All basic information on lost follow-up was available in a previous study [24] and Supplementary materials. Cases with too many missing confounders were eliminated, leaving 19,170 singleton pregnancies and birth outcomes. Details are in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of data collection in this study

Variables

Time division

The COVID-19 pandemic was first reported in Wuhan at the end of 2019 and spread rapidly across China. Each province continuously and frequently adjusted its pandemic control strategies according to the local pandemic situation. Although the pandemic situation and prevention and control policies of each province at the same time point from 2020 to 2022 may be different, on the whole, China did not remove control until the end of 2022. Therefore, we roughly regard the period before 2020 as pre-pandemic and the period from 2020 to 2022 as the pandemic in Southwest China. Pregnancies with a presumed pregnancy date before 2020 were considered to be pre-pandemic, and those with a presumed pregnancy date later were considered to be post-pandemic.

Outcome variables

LBW denotes low birth weight (less than 2,500 g). PTB represents preterm birth (delivery gestational age less than 37 weeks). Apgar score (1 min) < 7 indicates poor health status. CAs refer to congenital anomalies (including congenital defects discovered after birth only).

Factor variables

ART (yes = 1, no = 0) signifies pregnancy achieved through ART.

Confounding variables

We divided annual household income into four levels: 0 (≥ 200,000 yuan), 1 (< 200,000 yuan), 2 (< 100,000 yuan) and 3 (< 60,000 yuan). For ethnicity, 0 represented the Han, and 1 represented all other ethnic minorities. Maternal age at delivery was divided into four grades: 0 (< 25 years), 1 (< 30 years), 2 (< 35 years) and 3 (≥ 35 years). Education level was divided into four levels: 0 (college and above), 1 (junior college), 2 (high school) and 3 (junior high school and below). Subjective health before pregnancy was rated on a 3-point scale: 1 (very good), 2 (good) and 3 (fair or below). For supplements, 1 was assigned for the supplementation of vitamins or minerals during pregnancy and 0 for no additional supplements. For delivery, 1 indicated delivery in county-level institutions and 0 for delivery in city-level and above institutions. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) ≥ 24 was scored 1, and < 24 was 0. Regarding parity, 1 was assigned for the first birth and 0 for the second or more.

Data analysis

Comparing changes in incidence rates of ART and birth outcomes before and after the pandemic

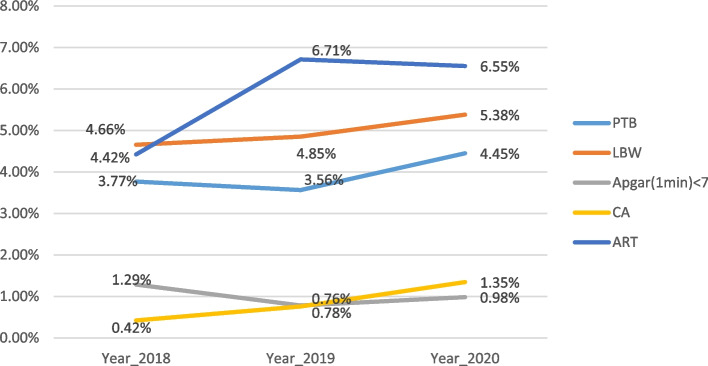

The chi-square test was employed in Rstudio 4.3.1 for comparing and analysing the differences in incidence rates of ART utilisation and various birth outcomes before and after the pandemic outbreak during two consecutive periods—from natural trends observed between 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 among pregnant women (Table 1). The results were also presented graphically (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Incidence of assisted reproductive technology and adverse birth outcomes from 2018 to 2020

| Variables | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019–2018 | 2020–2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Rate diff | P | Rate diff | P | ||

| LBW | yes | 340 | 3.77 | 155 | 3.56 | 258 | 4.45 | − 0.21% | 0.646 | 0.89% | 0.030 |

| No | 8682 | 96.23 | 4195 | 96.44 | 5540 | 95.55 | |||||

| PTB | yes | 420 | 4.66 | 211 | 4.85 | 312 | 5.38 | 0.20% | 0.623 | 0.53% | 0.256 |

| No | 8602 | 95.34 | 8278 | 190.30 | 5174 | 89.24 | |||||

|

Apgar (1 min) < 7 |

yes | 116 | 1.29 | 34 | 0.78 | 57 | 0.98 | − 0.50% | 0.012 | 0.20% | 0.340 |

| No | 8906 | 98.71 | 4282 | 98.44 | 5684 | 98.03 | |||||

| CA | yes | 38 | 0.42 | 33 | 0.76 | 78 | 1.35 | 0.34% | 0.089 | 0.59% | 0.102 |

| No | 8984 | 99.58 | 4317 | 99.24 | 5720 | 98.65 | |||||

| ART | yes | 399 | 4.42 | 292 | 6.71 | 380 | 6.55 | 2.29% | < 0.001 | − 0.16% | 0.752 |

| No | 8623 | 95.58 | 4058 | 93.29 | 5418 | 93.45 | |||||

| sum | 9022 | 100.00 | 4350 | 100.00 | 5798 | 100.00 | |||||

Fig. 3.

Incidence of assisted reproductive technology and adverse birth outcomes from 2018 to 2020

Analysing the change in the probability of ART-related adverse birth outcomes before and after the pandemic

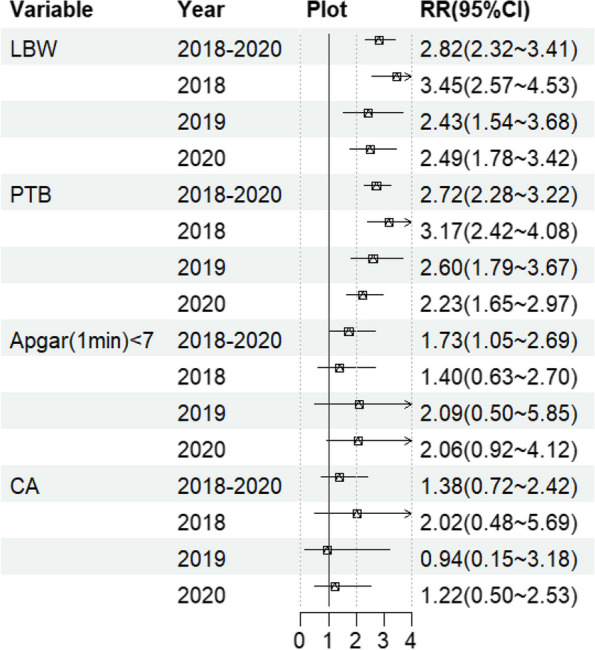

The log-binomial regression model in R software was employed to analyse the changes in the probability of adverse birth outcomes related to ART before and after the pandemic while controlling for confounding factors such as family annual income, maternal ethnicity, delivery age, subjective prenatal health status, vitamin or mineral supplementation during pregnancy and level of prenatal care provided by the hospital. The resulting probabilities of ART-related adverse birth outcomes were plotted to illustrate their temporal variation from 2018 to 2020 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Strength of the association between assisted reproductive technology and birth outcomes from 2018 to 2020. *The adjusted variables considered in this study encompass annual household income, ethnicity, maternal age at delivery, educational attainment, self-reported health status prior to pregnancy, vitamin or mineral supplementation status, hospital classification, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and parity

Other predictors of adverse birth outcomes

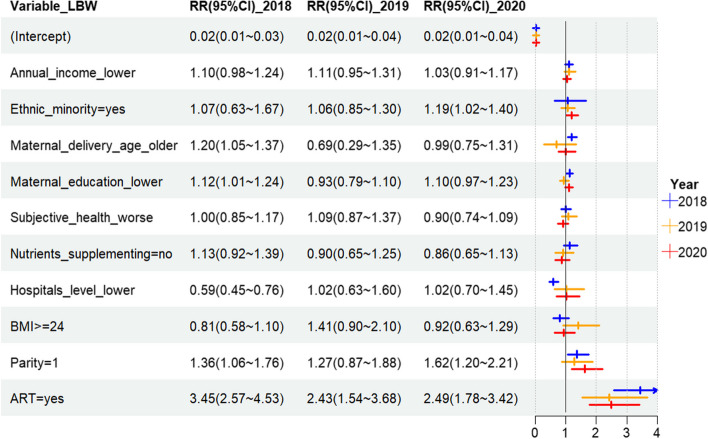

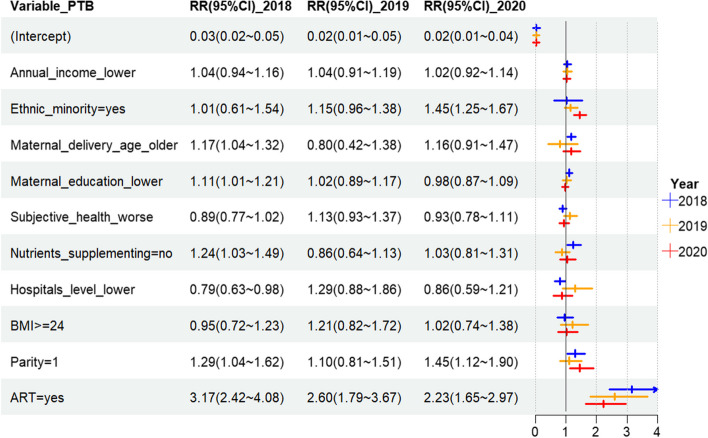

The ‘forestplot’ and ‘forestploter’ packages were used for forest mapping in R version 4.3.1 to demonstrate the predictors associated with LBW and PTB in 2018–2020 (Figs. 5 and 6) and compare the strength of association between various predictors and adverse birth outcomes.

Fig. 5.

Predictive power of influencing factors on low birth weight from 2018 to 2020. *The adjusted variables encompass all other factors listed in the variable column

Fig. 6.

Predictive power of influencing factors on preterm birth from 2018 to 2020. *The adjusted variables encompass all other factors listed in the variable column

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was received from the Sichuan University Medical Ethical Review Board (K2016038).

Informed consent

All the subjects agreed to participate in this study and signed an informed consent form on the premise that they fully understood the purpose, content and investigation procedures of this study.

Results

Changes in ART and birth outcomes before and after the pandemic

Before the pandemic, the ART rate increased from 4.42% in 2018 to 6.71% in 2019 (rate difference of 2.29%). After the pandemic, the ART rate decreased from 6.71% in 2019 to 6.55% in 2020 (rate difference of − 0.16%) (refer to Table 1). These findings suggest a potential decline in ART pregnancies during the pandemic.

Compared with those in the pre-pandemic period, each adverse pregnancy outcome exhibited varying changes following the pandemic (Fig. 3). The rate difference for LBW decreased from − 0.21% before the pandemic to an increase of + 0.89% afterwards. Similarly, PTB showed an increase from a rate difference of + 0.20% before the pandemic to + 0.53% afterwards. Furthermore, Apgar score < 7 at 1 min had a negative rate difference of − 0.50%, which changed to a positive value of + 0.20% after the pandemic. CA rate difference increased from + 0.34% prior to the outbreak to + 0.59% post-outbreak (Table 1). These observations indicate that the trends towards improved birth outcomes observed prior to the pandemic had slowed down or even reversed during this challenging period.

Comparison of characteristics between ART and spontaneous pregnancy

The proportion of ART women with annual household income of more than 100,000 yuan, ethnic minorities, delivery age over 30 years old, education level of high school or below, poor subjective health status before pregnancy, delivery in municipal and above institutions, pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 24 and first delivery was statistically significantly higher than that of women undergoing natural pregnancy. Compared with those with spontaneous pregnancy, ART women were more likely to give birth to babies with LBW and low Apgar scores and undergo PTB. Details can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of ART and non-ART women and their delivery outcomes

| Variables | non-ART | ART | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 18,099 (100%) | 1071 (100%) | |

| Annual household income | 0.017 | ||

| ≥ 200,000 yuan | 1923 (10.6) | 138 (12.9) | |

| < 200,000 yuan | 4662 (25.8) | 280 (26.1) | |

| < 100,000 yuan | 5085 (28.1) | 261 (24.4) | |

| < 60,000 yuan | 6429 (35.5) | 392 (36.6) | |

| Ethnic minority (yes) | 2035 (11.2) | 190 (17.7) | < 0.001 |

| Maternal age at delivery | < 0.001 | ||

| < 25 years | 3005 (16.6) | 100 (9.3) | |

| < 30 years | 8420 (46.5) | 357 (33.3) | |

| < 35 years | 5396 (29.8) | 421 (39.3) | |

| ≥ 35 years | 1278 (7.1) | 193 (18.0) | |

| Education level | 0.001 | ||

| College and above | 5754 (31.8) | 332 (31.0) | |

| Junior college | 5381 (29.7) | 273 (25.5) | |

| High school | 3649 (20.2) | 222 (20.7) | |

| Junior high school and below | 3315 (18.3) | 244 (22.8) | |

| Subjective health before pregnancy | 0.53 | ||

| Very good | 5744 (31.7) | 338 (31.6) | |

| Good | 9673 (53.4) | 561 (52.4) | |

| Fair or below | 2682 (14.8) | 172 (16.1) | |

| Supplement of vitamins or minerals during pregnancy(yes) | 7434 (41.1) | 400 (37.3) | 0.017 |

| Delivery in county-level institutions (yes) | 4516 (25.0) | 179 (16.7) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 24 (yes) | 2406 (13.3) | 168 (15.7) | 0.029 |

| Parity = 1 (yes) | 11,795 (65.2) | 853 (79.6) | < 0.001 |

| LBW (yes) | 632 (3.5) | 121 (11.3) | < 0.001 |

| PTB (yes) | 795 (4.4) | 148 (13.8) | < 0.001 |

| Apgar (1 min) score < 7 (yes) | 187 (1.0) | 20 (1.9) | 0.016 |

| CA (yes) | 137 (0.8) | 12 (1.1) | 0.255 |

Association between ART and adverse birth outcomes before and during the pandemic

Is there any association between adverse birth outcomes and ART? According to the pooled data from 2018 to 2020 after the adjustment for other factors, ART mothers had the highest probability of giving birth to LBW babies (relative risk (RR): 2.82, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.32–3.41), undergoing PTB (RR: 2.72, 95% CI: 2.78–3.22) and delivering babies with Apgar score < 7 (RR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.05–2.69). No significant difference in congenital malformations was observed between ART mothers and those with natural pregnancies (RR: 1.38, 95% CI: 0 0.72–2 0.42). Analysis of separate data before and during the pandemic revealed a shift from a decreasing to an increasing trend in the likelihood of LBW babies born to ART mothers due to the pandemic’s impact (RRs from 2018 to 2020: 3.45 → 2.43 → 2.49). Meanwhile, the reduction in PTB probability slowed down (RRs from 2018 to 2020: 3.17 → 2.60 → 2.23). Annual data did not show any statistically significant relationship between ART and Apgar scores. This finding suggests that the pandemic may have altered the decline rate of adverse birth outcomes among ART mothers.

Factors of adverse pregnancy outcomes before and during the pandemic

Figure 5 shows that prior to the pandemic outbreak in 2018 (pre-pandemic), ART was the most significant predictor of LBW, exhibiting an RR of 3.45 (95% CI: 2.57–4.53). Primiparity demonstrated a moderate association with LBW (RR:1.36, 95% CI: 1.06–1.76), followed by advanced maternal age (RR:1.20, 95% CI: 1.05–1.37) and low educational level (RR:1.12, 95% CI: 1.01–1.24). At post-outbreak in 2020, ART continued to be the primary predictor for LBW with an RR of 2.49 (95% CI: 1.78–3.42), followed by primiparity with an RR of 1.62 (95% CI: 1.20–2.21). Ethnic minority status also exhibited some influence on LBW with an RR of 1.19 (95% CI:1.02–1.40).

Figure 6 demonstrates that prior to the onset of the pandemic (2018), ART (RR:3.17, 95% CI: 2.42–4.08) was the most robust predictor of PTB, followed by primiparity (first-time mother) (RR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.04–1.62), inadequate nutrient supplementation (RR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.03–1.49), advanced maternal age (RR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.04–1.32) and low educational attainment level (RR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.01–1.21). At post-outbreak in 2020, the primary predictor for predicting PTB remained to be ART (RR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.65–2.97). Ethnic minority status (RR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.25–1.67) and primiparity (RR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.12–1.90) emerged as significant secondary predictors.

Discussion

Current situations of ART in Southwest China and comparison with other regions

The findings from research in Southwest China are consistent with those from multiple countries or regions worldwide [25], all of which demonstrate a high risk of LBW, PTB and birth defects among ART users. Some scholars reported the ART rate to be as high as 6.3% in Denmark, between 3 and 4% in Finland, Iceland and Sweden and approximately 2% in Switzerland [26]. Compared with Northern Europe, Southwest China exhibits a higher ART rate ranging from 4.42% to 6.71%. Inequities in birth outcomes between ART users and naturally conceived individuals are a significant social and public health concern that warrants top priority in areas with relatively elevated ART rates.

Causes of changes in ART and birth outcomes before and after the pandemic

In late 2019, a coronavirus outbreak emerged in China, prompting local governments to implement stringent control measures. In Southwest China, ART utilisation declined while the incidence of adverse birth outcomes continued to rise because of the pandemic. This contradictory trend deviates from previous studies that generally found a positive association between ART and adverse birth outcomes. The decrease in ART usage can be attributed to the early impact of the outbreak, with 63.3% of ART service providers and 95.5% of human sperm banks suspending operations in China [27]. The main reason for this decline in ART utilisation rate is the subjective adherence to government recommendations [28] to suspend or delay receiving ART services due to concerns about contracting COVID-19. To date, no evidence suggests that COVID-19 infection affects the successful pregnancy rate among ART users [29]. On the contrary, ample evidence indicates that ART services themselves do not lead to differences in birth outcomes compared with natural births [2–5]. The increase in adverse birth outcomes is attributed to the overall decline in technical service levels related to ART and delays caused by the pandemic’s impact on these services. For instance, during the pandemic, public medical institutions experienced a significantly higher drop in ART services compared with private institutions; given that certain high-tech services could only be provided by public institutions, this drop may have contributed to the decline in the overall quality of ART services [30]. Additionally, the disruption of ART services during the pandemic may have led to a decline in live births, particularly among older women. A delay of 6 months can result in a reduction of over 10% in the live birth rate for women aged 35 years and above, significantly increasing the likelihood of adverse birth outcomes for those who are compelled to postpone their receipt of ART services [31].

In addition to China, the rates of adverse birth outcomes have increased by 11%–30% in Nepal, Uruguay and California following the pandemic, with a concurrent rise in stillbirth rates [32]. During the initial months after the pandemic, Australia witnessed a decrease in PTB rate by 29%–36%, Israel by 40% and certain European countries by 16%–91%. Nevertheless, an increase in stillbirths and neonatal deaths was observed [32]. Precise evidence explaining these regional differences is currently lacking. The primary reason may be the heightened strain on healthcare systems due to the pandemic [33], such as the postpartum care service utilisation rate within the Boston area dropping to 41.7% during the early stages (1–3 months) of the pandemic before gradually rising to 60.9% four months later when COVID-19 became global [34]. Furthermore, the variations in medical care levels across different regions might have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

During the pandemic, the correlation strength of ART services with PTB and LBW increased. Additionally, the correlation of adverse birth outcomes with ethnic minorities and primiparas increased. Different from the findings of this study, the racial birth outcome disparity that existed before the pandemic in the United States did not change during the pandemic (2020/03–2021/04) [35]. This finding suggests that the degree of impact of the pandemic on different regions and populations with varying characteristics may be different. Primiparas may be highly affected by the reduction in healthcare services during pandemic control due to their lack of self-care experience. Meanwhile, ethnic minorities generally live in areas with poor medical resources, and the reduction in healthcare services may have a great impact on them.

Suggestions

As a form of specialised medical care, ART services have been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The resulting delays have had notable implications for patients’ birth outcomes. Global pandemics are not uncommon, as evidenced by historical events such as the HIN1 influenza pandemic of 1918, the Ebola virus pandemic of 2013 and the Zika virus pandemic of 2016. Therefore, conducting further research and considering strategies for planning and preparing ART services in anticipation of future pandemics are imperative. This approach may involve strengthening prenatal care and healthcare provisions specifically tailored to first-time mothers and ethnic minorities.

Strengths

The main advantages of this study are as follows: first, the study sample is large, and the design is a prospective cohort study, which has strong causal inference power and is suitable for studying adverse birth outcomes with relatively low incidence. Second, the baseline survey and follow-up before and after the pandemic comprised a natural intervention experiment, which is an excellent experimental design to study the impact of the pandemic on perinatal health. Third, this study found that the pandemic has magnified the existing inferior pregnancy outcomes of ART women. An in-depth analysis of the underlying reasons will provide a reference for further improving the quality of ART services in Southwest China and even all low- and middle-income countries or regions.

Limitations

This study also has some limitations. The findings of a survey conducted in Italy on women who gave birth during the pandemic revealed a decrease in physical exercise and an increase in anxiety and other negative emotions [36]. Several works suggested that the pandemic has affected the mental well-being of pregnant women [37, 38]. Therefore, future research should consider exploring mediation variable as mental health between ART and adverse birth outcomes. Secondly, vaccination status was not included in the present study; however, existing literature reviews indicated that vaccination does not affect the association between ART and birth outcomes [39, 40]. Lastly, due to limitations in its sample size, the present study was unable to differentiate between periods of severe and relatively mild pandemics. Hence, the results were less defined.

Conclusions

This study revealed the increased strength of association between ART and various adverse birth outcomes in Southwest China after the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the potential reasons is that during the pandemic, the public institutions providing high-end and complex ART technologies suspended their services. Only private institutions providing low-end technologies continued to operate. China needs to further strengthen the regulation and management of private ART providers to reduce potential harm to ART users’ birth outcomes caused by other public health events.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

J.H, J.L and W.L were responsible for study design and helped with drafting. Q.Z, J.Z, and M.L performed the data collection. D.H, P.Z, Y.Z and J.M performed the statistical analysis. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019

- ART

Assisted reproductive technology

- LBW

Low birth weight

- PTB

Preterm birth

- CAs

Congenital anomalies

- RR

Relative risk

- CI

Confidence interval

- BMI

Body mass index

Authors’ contributions

J.H, J.L and W.L were responsible for study design and helped with drafting. Q.Z, J.Z, and M.L performed the data collection. D.H, P.Z, Y.Z and J.M performed the statistical analysis. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program(MZGC20230065),the Sichuan Psychological Society project(SCSXLXH2023024) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China(2017YFC0907304).

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary material.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval can be seen in the article “Cohort Profile: China Southwest Birth Cohort (CSBC)”. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jinnuo Hu and Jiaxin Liu as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Zheng Y, Dong J. Comparison and analysis of clinical data characteristics of assisted reproduction between different countries and regions. J Reprod Med. 2024;33(2):187–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaat T, Zagers M, Mol F, Goddijn M, van Wely M, Mastenbroek S. Fresh versus frozen embryo transfers in assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2(2):CD011184. 10.1002/14651858.CD011184.pub3. Published 2021 Feb 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelikh A, Smith KR, Myrskylä M, Goisis A. Medically assisted reproduction treatment types and birth outcomes: a between-family and within-family analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(2):211–22. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goisis A, Remes H, Martikainen P, Klemetti R, Myrskylä M. Medically assisted reproduction and birth outcomes: a within-family analysis using Finnish population registers. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1225–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31863-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lei LL, Lan YL, Wang SY, Feng W, Zhai ZJ. Perinatal complications and live-birth outcomes following assisted reproductive technology: a retrospective cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(20):2408–16. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenfeld Z. Possible impact of COVID-19 on fertility and assisted reproductive technologies. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(1):56–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ata B, Vermeulen N, Mocanu E, et al. SARS-CoV-2, fertility and assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29(2):177–96. 10.1093/humupd/dmac037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue Y, Xiong Y, Cheng X, Li K. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on clinical outcomes of in vitro fertilization treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1233986. Published 2023 Oct 6. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1233986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hu W, Zhu Y, Wu Y, Wang F, Qu F. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the pregnancy outcomes of women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques (ARTs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2022;23(8):655–65. 10.1631/jzus.B2200154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutting E, Catt S, Vollenhoven B, Mol BW, Horta F. The impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on fertility patients and clinics around the world. Reprod Biomed Online. 2022;44(4):755–63. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ESHRE COVID-19 Working Group , Vermeulen N, Ata B, et al. A picture of medically assisted reproduction activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020(3):hoaa035. Published 2020 Aug 17. 10.1093/hropen/hoaa035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.L Xuefeng, T Yulin, H Chuan, et al. Analysis of the recruitment of human sperm bank in the post-epidemic period. Chin J Androl. 2021;(6):29. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0848.2021.06.006.

- 13.Jamieson DJ, Rasmussen SA. An update on COVID-19 and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):177–86. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published correction appears in Lancet Glob Health. 2021 Jun;9(6):e758]. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e759–72. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei SQ, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Liu S, Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2021;193(16):E540–8. 10.1503/cmaj.202604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Been JV, Burgos Ochoa L, Bertens LCM, et al. Impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth: a national quasi-experimental study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(11):e604–11. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berghella V, Boelig R, Roman A, et al. Decreased incidence of preterm birth during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(4): 100258. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasuga Y, Tanaka M, Ochiai D. Preterm delivery and hypertensive disorder of pregnancy were reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single hospital-based study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46(12):2703–4. 10.1111/jog.14518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kc A, Gurung R, Kinney MV, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1273–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayaz R, Hocaoğlu M, Günay T, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in the same pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Perinat Med. 2020;48(9):965–70. 10.1515/jpm-2020-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumari V, Mehta K, Choudhary R. COVID-19 outbreak and decreased hospitalisation of pregnant women in labour. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1116–7. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torche F, Nobles J. The Unequal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Infant Health. Demography. 2022;59(6):2025–51. 10.1215/00703370-10311128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(1):15–27. 10.1002/uog.22088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Z, Liu W, Hu J, et al. Cohort Profile: China Southwest Birth Cohort (CSBC). Int J Epidemiol. 2023;52(6):e347–53. 10.1093/ije/dyad103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuzaki S, Masjedi AD, Matsuzaki S, et al. Obstetric characteristics and outcomes of gestational carrier pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2422634. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22634. Published 2024 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Geyter C. Assisted reproductive technology: Impact on society and need for surveillance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33(1):3–8. 10.1016/j.beem.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei L, Zhang J, Deng X, et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Chinese assisted reproductive technology institutions and human sperm banks: reflections in the post-pandemic era. J Health Popul Nutr. 2023;42(1):82. 10.1186/s41043-023-00422-1. Published 2023 Aug 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith ADAC, Gromski PS, Rashid KA, Tilling K, Lawlor DA, Nelson SM. Population implications of cessation of IVF during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41(3):428–30. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaur H, Chauhan A, Mascarenhas M. Does SARS Cov-2 infection affect the IVF outcome - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2024;292:147–57. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2023.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bithorel PL, de La Rochebrochard E. The COVID-19 crisis and ART activity in France. Reprod Biomed Online. 2023;46(5):877–80. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2023.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharya S, Maheshwari A, Ratna MB, van Eekelen R, Mol BW, McLernon DJ. Prioritizing IVF treatment in the post-COVID 19 era: a predictive modelling study based on UK national data. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(3):666–75. 10.1093/humrep/deaa339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calvert C, Brockway MM, Zoega H, et al. Changes in preterm birth and stillbirth during COVID-19 lockdowns in 26 countries. Nat Hum Behav. 2023;7(4):529–44. 10.1038/s41562-023-01522-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashem NM, Abdelnour SA, Alhimaidi AR, Swelum AA. Potential impacts of COVID-19 on reproductive health: Scientific findings and social dimension. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(3):1702–12. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mi T, Hung P, Li X, McGregor A, He J, Zhou J. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care in the greater boston area during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6): e2216355. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16355. Published 2022 Jun 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molina RL, Tsai TC, Dai D, et al. Comparison of Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes Before vs During the COVID-19 Pandemic [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Sep 1;5(9):e2233824] [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May 1;6(5):e2314781]. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2226531. Published 2022 Aug 1. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.26531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Stampini V, Monzani A, Caristia S, et al. The perception of Italian pregnant women and new mothers about their psychological wellbeing, lifestyle, delivery, and neonatal management experience during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a web-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):473. Published 2021 Jul 1. 10.1186/s12884-021-03904-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic [published correction appears in J Affect Disord. 2021 Jan 15;279:377–379]. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:5–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Birkelund KS, Rasmussen SS, Shwank SE, Johnson J, Acharya G. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s perinatal mental health and its association with personality traits: n observational study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102(3):270–81. 10.1111/aogs.14525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chamani IJ, Taylor LL, Dadoun SE, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination and assisted reproduction outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2024;143(2):210–8. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y, Dong Y, Li G, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following natural conception and assisted reproduction treatment in women who received COVID-19 vaccination prior to conception: a population-based cohort study in China. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10: 1250165. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1250165. Published 2023 Oct 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the supplementary material.