Abstract

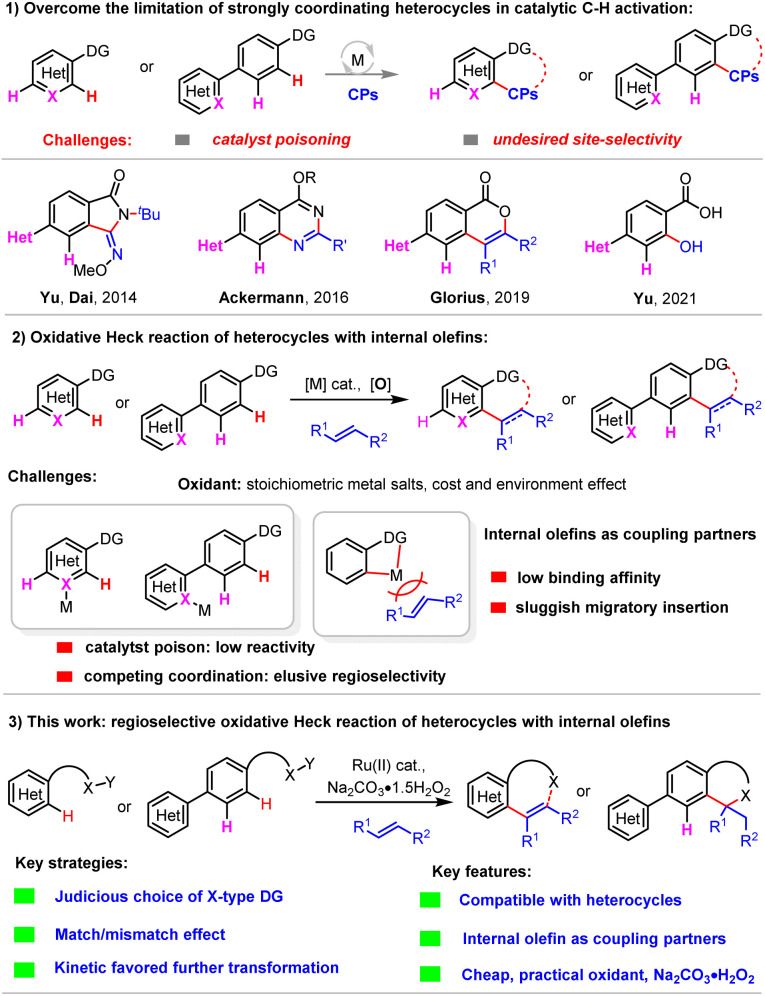

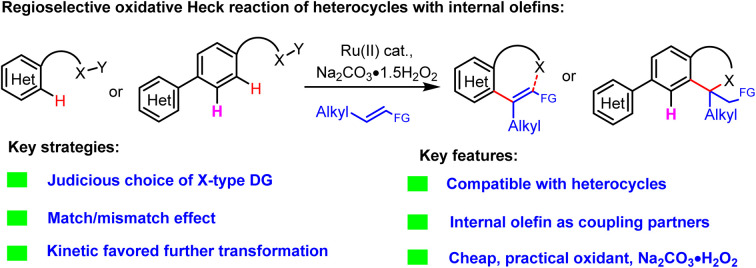

The oxidative Heck reaction of strongly coordinating heterocycles with internal olefins often led to elusive reactivity and regioselectivity. Herein, by judicious choice of X-type directing groups under Ru(ii) catalysis, we achieved the regioselective oxidative Heck reaction of strongly coordinating heterocycles with sterically demanding internal olefins. It was postulated that the “match/mismatch effect” of sterically demanding internal olefins as coupling partners and subsequent kinetically favoured Michael addition or oxidative aromatization act as driving forces to facilitate the desired reactivity and site-selectivity.

By using imidate esters, oxidative Heck reaction of strongly coordinating heterocycles with internal olefins was achieved with good reactivity and regioselectivity.

Introduction

The directing strategy-enabled oxidative Heck reaction (Fujiwara–Moritani reaction) has proven to be reliable for the expedient construction of olefins and ring systems, featuring step-economy and exquisite reactivity and selectivity.1 Despite significant advancement in the development of metal catalysts and directing groups, there remained some limitations: (1) sterically demanding internal olefins2 as coupling partners often exhibited low reactivity, probably due to the low binding affinity of internal olefins toward the metallocycle species and sluggish migratory insertion; (2) elusive reactivity and regioselectivity posed by the unproductive coordination of Lewis basic nitrogen and sulfur atoms of the heterocycle substrates; (3) costly stoichiometric metal oxidants3 were commonly employed which offset the synthetic advantages.

Currently, only limited success was obtained using sterically demanding internal olefins for the oxidative Heck reaction by meticulous design of directing groups and ligands under metal catalysis. Yu2a–g developed MPAA (mono-N-protected amino acids) and heterocycle ligands to promote the oxidative Heck reaction enabled by weak coordination compatible with internal olefin coupling partners.

Moreover, regioselective enhancement of strongly coordinating heterocycles remained synthetically appealing and challenging. In this context, Yu and Dai developed a Pd-catalyzed C–H activation with isonitriles that overrides the limitation of strongly coordinating heterocycles, using N–OMe amides as the sole ionic ligands and directing groups, where the formed localized PdIIX2 active species could cleave the specific C–H bonds.4a Ackermann demonstrated Co(iii)-catalyzed imidate enabled C–H amidation and annulation cascade with well-tolerated heterocycles.4b–d Glorius reported Ru-catalyzed C–H annulation with propargyl alcohol carbonates and an array of N-heterocycles.4e Recently, using a well-designed N,N bidentate tautomerizable pyridine-based ligand, Yu realized Pd(ii)-catalyzed C–H oxygenation of heterocycles with molecular oxygen, in which strongly coordinating heterocycles are compatible (Scheme 1).4f

Scheme 1. Regioselective oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins that tolerated strongly coordinating heterocycles.

Despite great advancement witnessed for the directed oxidative Heck reaction, including the development of green catalytic systems and synthetic application towards biologically active molecules,5–8 sterically demanding internal olefins with compatible strongly coordinating heterocycles remained underexplored.

Herein, by judicious choice of X-type directing groups, imidate esters, we developed the Ru(ii)-catalyzed oxidative Heck reaction7,8 of heterocycles with internal olefins, using the Na2CO3·H2O2 oxidant and biomass-derived solvent. Significantly, regioselective modification of complex pharmaceuticals that contained multiple functionalities, e.g., celecoxib that contained strongly coordinating heterocycles, was realized.

Results and discussion

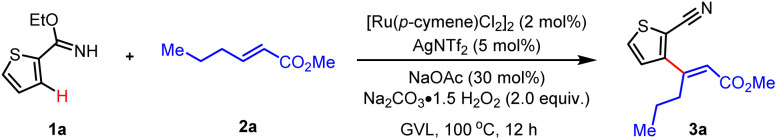

We commenced our study on the oxidative Heck reaction by using imidate ester 1a9,10 and internal olefin 2a as the model substrates. Optimization of reaction conditions revealed that with Ru[(p-cymene)Cl2]2 and AgNTf2 as the catalyst, NaOAc as the base, Na2CO3·1.5H2O2 as the practical and inexpensive oxidant, and biomass-derived GVL (γ-valerolactone) as the sustainable solvent, the desired olefin 3a was obtained in good yield (Table 1, entry 1). The Rh(iii) complex exhibited comparable reactivity, whereas other metal complexes such as Pd(ii), Ni(ii), Ir(iii) complex candidates showed no reactivity (entries 2 and 3). Control experiments indicated that the Ru(ii) catalyst was essential, and AgSbF6 could also serve as a halide scavenger to facilitate the generation of cationic Ru(ii) catalytically active species (entries 4–6).

Oxidative Heck reaction of heterocycles with internal olefinsa.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation of standard conditions | Yieldb (%) |

| 1 | Standard conditions | 76 |

| 2 | Pd(OAc)2, NiCl2 or [IrCp*Cl2]2 as the catalyst | n.r. |

| 3 | [RhCp*Cl2]2 as the catalyst | 73 |

| 4 | AgSbF6 instead of AgNTf2 | 65 |

| 5 | Without [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | n.r. |

| 6 | Without AgNTf2 | 27 |

| 7 | Without NaOAc | Trace |

| 8 | HOAc, PivOH instead of NaOAc | 30, 38 |

| 9 | NaOTFA, NaOPiv instead of NaOAc | 56, 67 |

| 10 | Without Na2CO3·1.5H2O2 | 24 |

| 11 | AgOAc, DTBP or Cu(OAc)2 as the oxidant | 68, trace, 66 |

| 12 | DCE, acetone, tBuOH, EA as the solvent | 72, 34, 53, 22 |

| 13 | 30 °C, 60 °C or 80 °C | Trace, trace, 46 |

| 14 | 1-AdCO2H (0.5 equiv.), EtOH | <10 |

Standard conditions: 1a (0.10 mmol), 2a (0.20 mmol), [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (2 mol%), AgNTf2 (5 mol%), NaOAc (30 mol%), Na2CO3·H2O2 (2.0 equiv.), GVL (1.0 mL), 100 °C, 12 h.

Isolated yield.

The utilization of acid, including HOAc, HOPiv or acetate salts such as NaOTFA or NaOPiv instead of NaOAc gave no improvement in the yield of 3a (entries 7–9). The Cu(ii) salt and Ag(i) oxidant effectively promoted the reaction with moderate yields, while DTBP prohibited the reactivity. It is noteworthy that Na2CO3·1.5H2O2 could serve as the synthetically practical oxidant (entries 10–12). DCE was also an amenable solvent to give comparable efficiency (entry 12). Reactions with decreased temperature furnished the desired product 3a in much lower yields (entry 13). Notably, only trace production of 3a was observed under Jeganmohan's conditions7 (entry 14).

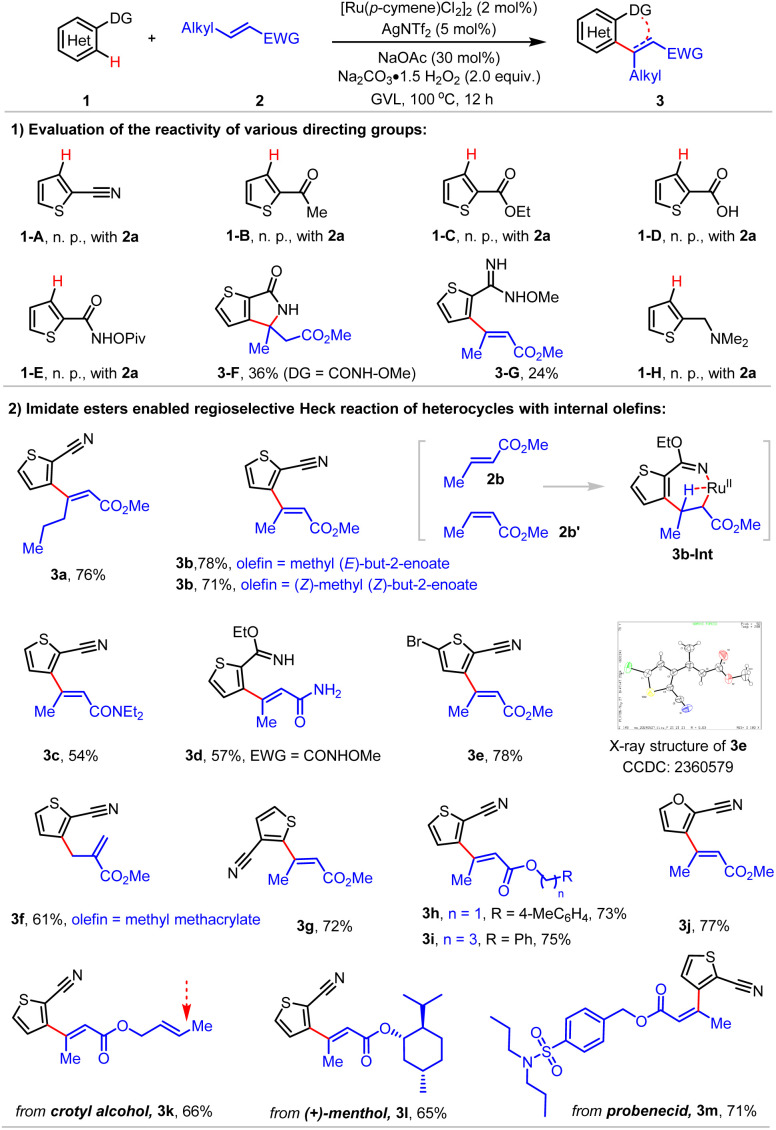

We then moved to examine reactivity of various directing groups for the oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins conducted under optimal Ru(ii) catalysis (Scheme 2). Notably, nitrile showed no reactivity (1-A), indicating that this transformation proceeded via the imidate ester directed oxidative Heck reaction where base promoted elimination of EtOH gave the desired product 3a. Moreover, ketone (1-B), ester (1-C) or carboxylic acid (1-D), and other X-type ligands such as N–OPiv amide (1-E) or NMe2 (1H) showed no reactivity.

Scheme 2. Regioselective oxidative Heck reaction of heterocycles with internal olefins.

The oxidative Heck reaction followed by Michael addition proceeded smoothly for internal oxidizing N–OMe amide (3-F). N–OMe-2-carboximidamide was also applicable for the stereoselective construction of tri-substituted olefins (3-G).

C2- and C3-substituted thiophenes (3a–3e) and furans (3j) led to tri-substituted olefins with exquisite stereoselectivity, which was confirmed by X-ray analysis (3e). Internal olefins including (E)-hex-2-enoates (3a), (E)-but-2-enoates (3e–3i) and (E)-but-2-enamides (3c and 3d) acted as amenable coupling partners. Notably, the reactions of both (E)-but-2-enoate 2b and methyl (Z)-but-2-enoate 2b′ as the coupling partners furnished the identical product 3b, indicating that intermediate 3b-Int that was enabled by imidate ester 1a under this Ru(ii) catalysis might be involved. Additionally, the oxidative Heck reaction with methyl methacrylate took place at the allylic C(sp3)-H position, affording α-olefin 3f as the sole product. Site-selective functionalization of natural products and drugs, including crotonate (3k), (+)-menthol (3l) and probenecid (3m) was also achieved.

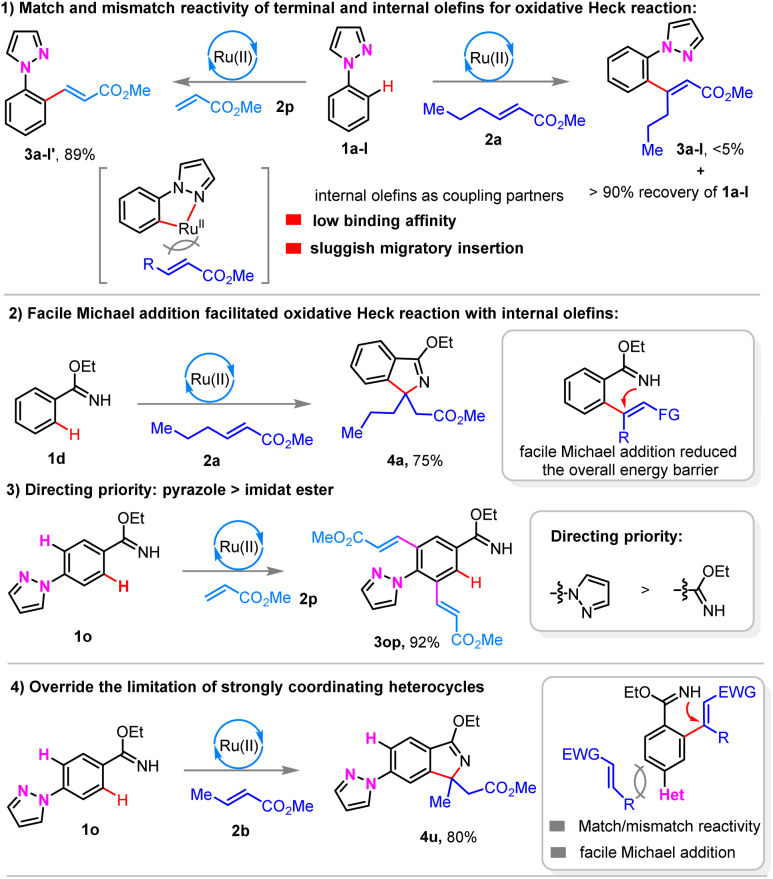

Preliminary mechanistic studies indicated that the oxidative Heck reaction of N-phenyl pyrazole 1a-I with terminal olefin 2o proceeded smoothly, while the use of internal olefin 2a led to low conversion with recovery of starting material 1a-I (Scheme 3(1)). The observed results might be attributed to the low binding affinity of sterically demanding internal olefins to the in situ formed metallocycles via directed C–H activation, and subsequent sluggish migratory insertion.

Scheme 3. Preliminary mechanistic studies.

Intriguingly, imidate ester 1d was applicable in the oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefin 2a, affording isoindole product 4a in a high yield (Scheme 3(2)). Moreover, the oxidative Heck reaction of pyrazole substituted acrylamide ester 1o with terminal olefin 2m gave olefination product 3op exclusively, indicating that the directing priority is that pyrazole is superior to imidate ester (Scheme 3(3)). Significantly, sterically demanding internal olefins 2 led to complementary regioselectivity (Scheme 3(4)).

Scheme 4. Regioselective oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins.

The facile Michael addition was envisaged to reduce the overall energy barrier, thus facilitating the oxidative Heck reaction with sterically demanding internal olefins. Consequently, terminal and sterically demanding internal olefins showed the ‘match and mismatch effect’4e for the directing strategy enabled oxidative Heck reaction, respectively, even using strongly coordinating heterocycles. Furthermore, this ‘match/mismatch effect’ could be tuned by the incorporation of X-type directing groups, in which the following facile transformation could accelerate the overall oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins, and thus, compatible with strongly coordinating heterocycles.

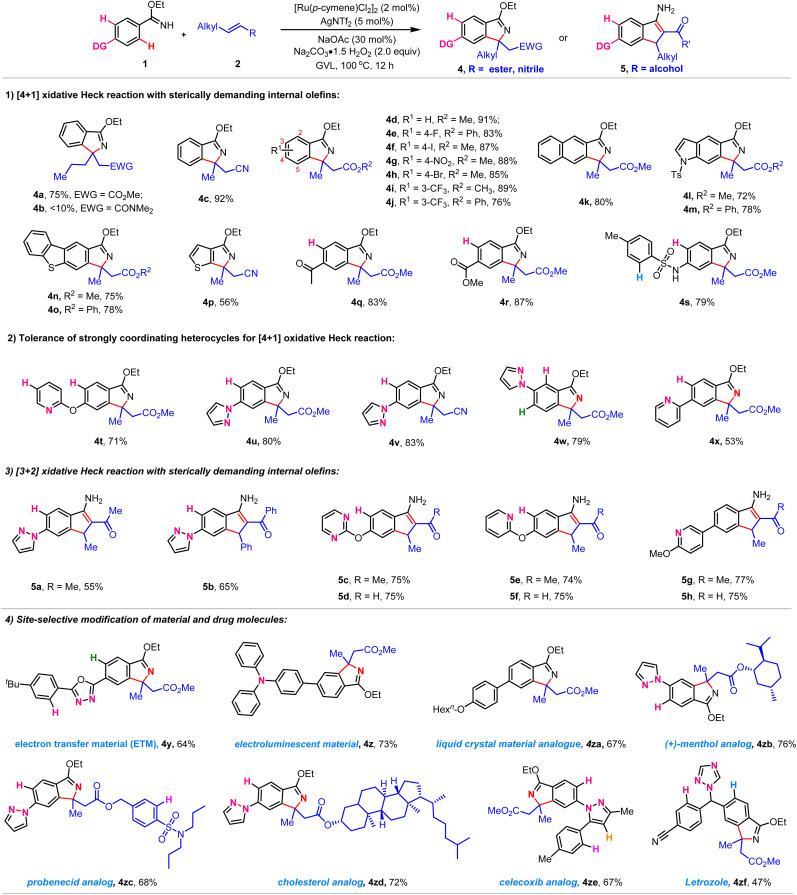

We thus investigated the imidate ester assisted oxidative Heck reaction (Scheme 4). The internal olefins bearing stronger electron-withdrawing nitrile (4c) exhibited better performance than ester, while crotonamide showed low reactivity (4b), which is probably due to the relative reactivity of these olefins for the further Michael addition step. Synthetically versatile functionalities including fluoride (4e), bromide (4h), iodide (4f), and nitro (4g) were tolerated. This oxidative Heck showed high regioselectivity and took place at less steric positions (4i and 4j). The reactions with fused ring systems including naphthalene (4k), indole (4l and 4m), dibenzo[b,d]thiophene (4n and 4o) proceeded smoothly. Notably, imidate esters exhibited directing priority to the competing coordinating ketone (4q), ester (4r), N–Ts aniline (4s), and O-bridged pyridine (4t) in this transformation. The oxidative Heck reaction of imidate esters with internal olefins is accessible in the presence of strongly coordinating heterocycles including pyrazole (4u and 4v). For meta-pyrazole acrylamide ester that contained multiple reactive C–H bonds, the oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins took place exclusively at the ortho position to imidate ester with less steric hindrance (4w). Significantly, commonly strongly coordinating pyridine could be also compatible for this imidate ester enabled oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins (4x).

We then performed site-selective functionalization of key skeletons of materials and drugs (Scheme 4(4)). For instance, 2,5-diaryl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles, potent scaffolds for electron transfer materials (ETM), underwent the regioselective oxidative Heck reaction successfully (4y). Triphenylamine (TPA), an electroluminescent material, was also an amenable substrate (4z). Natural products and drugs including (+)-menthol (4zb), probenecid (4zc), and cholesterol (4zd) derived internal olefins could serve as coupling partners for this oxidative Heck reaction.

Celecoxib analogue derived imidate ester, bearing diverse reactive C–H bonds, could assist the regioselective oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins (4ze). Late-stage modification of the letrozole drug analogue, which contained triazole and nitrile functionalities (4zf), was achieved. The observed high reactivity and regioselectivity for complex drugs and materials further demonstrated the synthetic potential of this oxidative Heck reaction with sterically demanding internal olefins in the presence of strongly coordinating heterocycles.

Further investigation of electron-unbiased allylic alcohols as the coupling partners11 disclosed that imidate esters enabled the [3 + 2] oxidative Heck reaction regioselectively. Notably, strongly coordinating heterocycles, including pyrazole (5a and 5b), pyridine (5g and 5h) and oxygen-bridged pyridine (5c and 5d), and oxygen-bridged pyrimidine (5e and 5f) were compatible for this regioselective oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins, furnishing indenes together with the release of ethanol and water. The obtained diverse indenes contained carbonyl and amine functionalities, which could serve as a synthetic handle for the synthesis of heterocycles (please see the ESI† for further discussion).

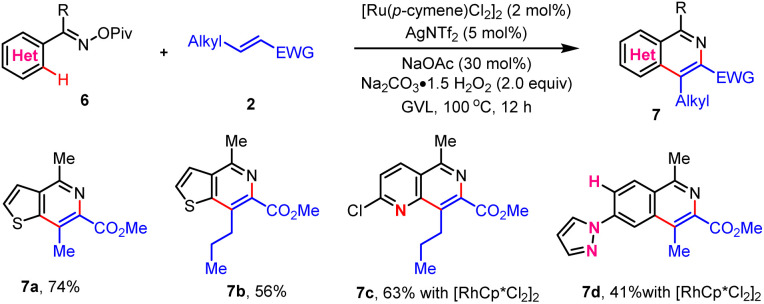

The oxime enabled Heck reaction has been demonstrated for the construction of heterocycles, while the use of heterocycles and sterically demanding internal olefin partners remained elusive to achieve regioselectivity and efficiency.12 Herein, we found that N–OPiv oxime esters could well assist the oxidative Heck reaction with sterically demanding internal olefins, affording fused heterocycles (Scheme 5), including thieno[3,2-c]pyridines (7a and 7b). Notably, 1,6-naphthyridines (7c) could be readily accessed, which exhibited superior performance in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs),12g while typical procedures suffered from limited substrate availability and harsh conditions. Moreover, this N–OPiv oxime enabled regioselective Heck reaction could also tolerate pyrazole (7d). It was speculated that the mismatch reactivity of pyrazole to the sterically demanding internal olefins and the oxidative Heck reaction followed by aromatization serve as key driving forces to the observed reactivity and regioselectivity.

Scheme 5. N–OPiv oxime enabled oxidative Heck reaction of heterocycles with sterically demanding internal olefins.

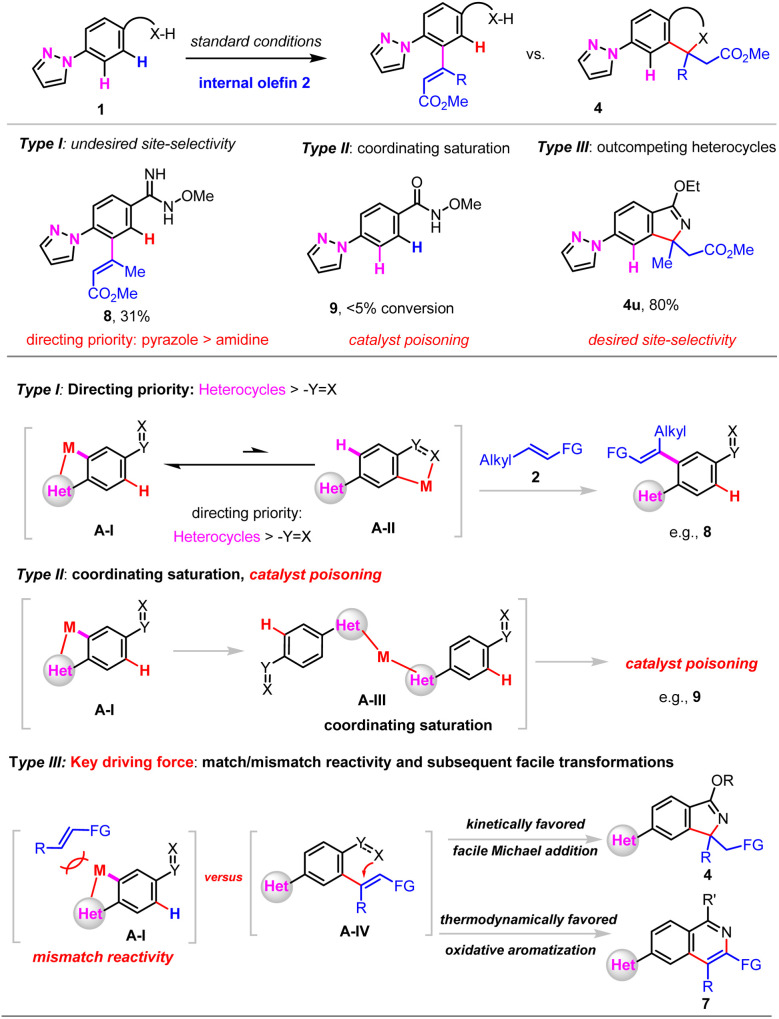

Extensive exploration of the reactivity of various X-type nitrogen directing groups revealed that the oxidative Heck reaction of N-methoxy benzimidamide 1a-I took place at the ortho position to pyrazole, which indicated that pyrazole showed directing priority to N–OMe benzimidamide. As for pyrazole substituted N–OMe amide 1a-II might be responsible for the coordinative saturation of pyrazole to the metal catalyst, thus leading to catalyst poisoning (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Mechanistic studies.

According to the experimental observations and related references, three typical reaction types might be involved in directed C–H functionalization of heterocycles. For type I reactivity, competing coordination of directing groups (DG) and heterocycles to the metal catalyst revealed that heterocycles showed directing priority to the DG, and undesired regioselectivity was often obtained, e.g., 8 (Scheme 6(1)).13,14

For type II reactivity, the strongly coordinating heterocycles led to coordinating saturation and catalyst poisoning, and thus, recovery of the starting materials, e.g., 9.

For type III reactivity, by judicious choice of X-type directing groups and exploring the match/mismatch effect (e.g., steric effect, low affinity of internal olefins for the oxidative Heck reaction in this work), as well as facile subsequent transformations (e.g., kinetically favoured facile Michael addition, or thermodynamically favoured aromatization with the release of small molecules) to reduce the overall energy barrier, C–H functionalization that overrides the limitation of strongly coordinating heterocycles might be achieved.15

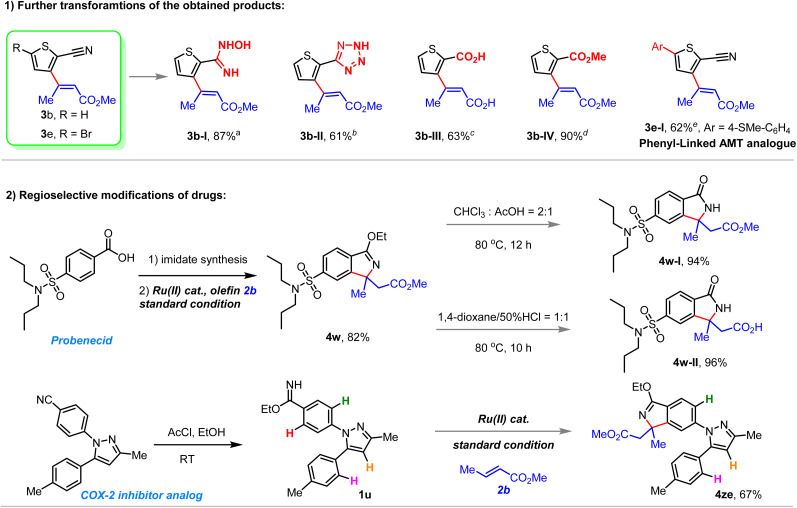

The native functionality-enabled oxidative Heck reaction of heterocycles with internal olefins remains underexplored; so while considering the versatile nitrile functionality, we thus conducted selective modification of the obtained products (Scheme 7). Nitrile in the product 3b was a versatile handle to an array of functionalities, including N-hydroxy carboximidamide (3b-I), tetrazole (3b-II), carboxylic acid (3b-III) and ester (3b-IV), which thus complement this directing strategy enabled oxidative Heck reaction of heterocycles with internal olefins (Scheme 7(1)).

Scheme 7. Synthetic transformations. Conditions: (a) 3b (0.1 mmol), NaOAc (2.0 equiv.), NH2OH·HCl (2.0 equiv.), MeOH/H2O (1.0 mL/1.0 mL), 90 °C, 2 h; (b) 3b (0.1 mmol), NaN3 (4.0 equiv.), NH4Cl (2.0 equiv.), DMF (1.0 mL), N2, 120 °C, 24 h; (c) 3b (0.1 mmol), NaOH aqueous solution (3 equiv., 3 M), 80 °C, 15 h; (d) 3b-V (0.05 mmol), K2CO3 (2.0 equiv.), MeI (2.0 equiv.), THF (1.0 mL), 40 °C, 5 h; (e) 3e (0.10 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.005 mmol), K2CO3 (0.4 mmol), Ar–B(OH)2 (0.12 mmol), EtOH/H2O/toluene = (0.3 mL/0.4 mL/1.0 mL), 95 °C, 12 h.

Moreover, Suzuki coupling of thiophene 3e proceeded to give phenyl-linked AMT analogue 3e-I, which further demonstrated the synthetic applications of this oxidative Heck reaction of heterocycles (please see the ESI† for details on the further synthetic applications).

Site-specific functionalization of drugs was also performed (Scheme 7(2)), e.g. the probenecid analogue (4w) could be further transformed to the corresponding isoindolin-1-ones (4w-I and 4w-II). Significantly, site-selective modification of the celecoxib analogue that contained diverse directing groups, using this internal olefin participated oxidative Heck reaction, proceeded smoothly that overrides the traditional directing priority (4ze). This transformation provided valuable insight into the precise modification of complex molecules that contained multiple reactive C–H bonds.

Conclusions

In summary, by judicious choice of X-type N-directing groups, we developed imidate ester enabled regio- and stereo-selective oxidative Heck reactions with internal olefins that tolerated strongly coordinating heterocycles. The match/mismatch effect and subsequent kinetically or thermodynamically favourable transformations served as key driving forces to achieve promising efficiency and regioselectivity. Synthetic applications were demonstrated by rapid construction of molecular libraries of heterocycle-containing drugs and materials, and modification of functional molecules that contained diverse functionalities with unconventional regioselectivity. Further exploration of the synthetic potential of this site-selective C–H functionalization that overrides the strongly coordinating heterocycles towards materials and drugs is underway.

Data availability

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the ESI.†

Author contributions

X. Li conceived and directed the project. C. Chen and Q. Zhang performed the experiments, analysed the results and contributed equally to this work. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22071034). We appreciate Prof. Zhe Wang at Guangdong University of Technology, Yu-Feng Liang at Shandong University, and Dr Zihang Qiu for the revision of this manuscript. We also thank the Instrumental Analysis Center of Guangdong University of Technology for their support.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. CCDC 2360579. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d4sc07036d

Notes and references

- (a) Heck R. F. Palladium-Catalyzed Reactions of Organic Halides with Olefins. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:146–151. doi: 10.1021/ar50136a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jia C. Kitamura T. Fujiwara Y. Catalytic Functionalization of Arenes and Alkanes via C–H Bond Activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:633–639. doi: 10.1021/ar000209h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) The Mizoroki-Heck Reaction, ed. M. Oestreich, Wiley, Chichester, 2009 [Google Scholar]; (d) Dounay B. Overman L. E. The Asymmetric Intramolecular Heck Reaction in Natural Product Total Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2945–2964. doi: 10.1021/cr020039h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on the directed oxidative Heck reaction with internal olefins: ; (a) Leow D. Li G. Mei T.-S. Yu J.-Q. Activation of Remote meta-C–H Bonds Assisted by an End-on Template. Nature. 2012;486:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature11158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang G. Lindovska P. Zhu D. Kim J. Wang P. Tang R.-Y. Movassaghi M. Yu J.-Q. Pd(II)-Catalyzed meta-C–H Olefination, Arylation, and Acetoxylation of Indolines Using a U-Shaped Template. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10807–10813. doi: 10.1021/ja505737x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu J. Chen J. Gao F. Xie S. Xu X. Jin Z. Yu J.-Q. Sequential Functionalization of meta-C–H and ipso-C–O Bonds of Phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:1903–1907. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Park H. Yu J.-Q. Palladium-Catalyzed [3 + 2] Cycloaddition via Twofold 1,3-C(sp3)–H Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:16552–16556. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang P. Jiang Z. Fan Z. Li G. Ma Q. Huang J. Tang J. Xu X. Yu J.-Q. Jin Z. Macrocyclization via Remote meta-Selective C–H Olefination Using a Practical Indolyl Template. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:8279–8287. doi: 10.1039/D3SC01670F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Bag S. Patra T. Modak A. Deb A. Maity S. Dutta U. Dey A. Kancherla R. Maji A. Hazra A. Bera M. Maiti D. Remote para-C–H Functionalization of Arenes by a D-Shaped Biphenyl Template-Based Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11888–11891. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yu Z. Liu Q. Li Q. Huang Z. Yang Y. You J. Remote Editing of Stacked Aromatic Assemblies for Heteroannular C–H Functionalization by a Palladium Switch between Aromatic Rings. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202212079P. doi: 10.1002/anie.202212079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on the aerobic oxidative Heck reaction with terminal olefins: ; (a) Zhang Y.-H. Shi B.-F. Yu J.-Q. Pd(II)-Catalyzed Olefination of Electron-Deficient Arenes Using 2,6-Dialkylpyridine Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5072–5074. doi: 10.1021/ja900327e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Engle K. M. Wang D.-H. Yu J.-Q. Ligand-Accelerated C–H Activation Reactions: Evidence for a Switch of Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14137–14153. doi: 10.1021/ja105044s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Engle K. M. Wang D.-H. Yu J.-Q. Constructing Multiply Substituted Arenes Using Sequential Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Olefination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:6169–6173. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Piotrowicz M. Zakrzewski J. Aerobic Dehydrogenative Heck Reaction of Ferrocene with a Pd(OAc)2/4,5-Diazafluoren-9-one Catalyst. Organometallics. 2013;32:5709–5712. doi: 10.1021/om400410u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (e) Piotrowicz M. Zakrzewski J. Metivier R. Brosseau A. Makal A. Wozniak K. Aerobic Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Heck Reaction in the Synthesis of Pyrenyl Fluorophores. A Photophysical Study of β-Pyrenyl Acrylates in Solution and in the Solid State. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:2573–2581. doi: 10.1021/jo502619k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Liu B. Jiang H.-Z. Shi B.-F. Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Olefination of Phenols Bearing Removable Directing Groups under Molecular Oxygen. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:1521–1526. doi: 10.1021/jo4027403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Cong X. Tang H. Wu C. Zeng X. Role of Mono-N-protected Amino Acid Ligands in Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Heck Reactions of Electron-Deficient (Hetero)arenes: Experimental and Computational Studies. Organometallics. 2013;32:6565–6575. doi: 10.1021/om400890p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (h) Huang Q. Zhang X. Qiu L. Wu J. Xiao H. Zhang X. Lin S. Palladium-Catalyzed Olefination and Arylation of Polyfluoroarenes Using Molecular Oxygen as the Sole Oxidant. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015;357:3753–3757. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201500632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (i) Xu Y.-H. Chok Y. K. Loh T.-P. Synthesis and Characterization of a Cyclic Vinyl-palladium(II) Complex: Vinylpalladium Species as the Possible Intermediate in the Catalytic Direct Olefination Reaction of Enamide. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:1822–1825. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00262G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Liu Y.-J. Xu H. Kong W.-J. Shang M. Dai H.-X. Yu J.-Q. Overcoming the Limitations of Directed C–H Functionalizations of Heterocycles. Nature. 2014;515:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang H. Lorion M. M. Ackermann L. Overcoming the Limitations of C–H Activation with Strongly Coordinating N-Heterocycles by Cobalt Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:10386–10390. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shang M. Wang M.-M. Saint-Denis T. G. Li M.-H. Dai H.-X. Yu J.-Q. Copper-Mediated Late-Stage Functionalization of Heterocycle-Containing Molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:5317–5321. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xu L.-L. Wang X. Ma B. Yin M.-X. Lin H.-X. Dai H.-X. Yu J.-Q. Copper Mediated C–H Amination with Oximes: en route to Primary Anilines. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:5160–5164. doi: 10.1039/C8SC01256C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu Q. Mondal S. Cembellín S. Greßies S. Glorius F. Site-selective C–H Activation and Regiospecific Annulation Using Propargylic Carbonates. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:6560–6564. doi: 10.1039/C9SC01703H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Li Z. Wang Z. Chekshin N. Qian S. Qiao J. X. Cheng P. T. Yeung K.-S. Ewing W. R. Yu J.-Q. A Tautomeric Ligand Enables Directed C–H Hydroxylation with Molecular Oxygen. Science. 2021;372:1452–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.abg2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For the oxidative Heck reaction of strongly coordinating heterocycles with terminal olefins: ; (a) Ye M. Gao G.-L. Yu J.-Q. Ligand-Promoted C-3 Selective C–H Olefination of Pyridines with Pd Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6964–6967. doi: 10.1021/ja2021075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dai H.-X. Stepan A. F. Plummer M. S. Zhang Y.-H. Yu J.-Q. Divergent C–H Functionalizations Directed by Sulfonamide Pharmacophores: Late-Stage Diversification as a Tool for Drug Discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7222–7228. doi: 10.1021/ja201708f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews: ; (a) Ma W. Gandeepan P. Li J. Ackermann L. Recent advances in positional-selective alkenylations: removable guidance for twofold C–H activation, Org. Chem. Front. 2017;4:1435–1467. doi: 10.1039/C7QO00134G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dhawa U. Kaplaneris N. Ackermann L. Green strategies for transition metal-catalyzed C–H activation in molecular syntheses. Org. Chem. Front. 2021;8:4886–4913. doi: 10.1039/D1QO00727K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Samanta R. C. Meyer T. H. Siewert I. Ackermann L. Renewable resources for sustainable metallaelectro-catalysed C–H activation. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:8657–8670. doi: 10.1039/D0SC03578E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shang X. Liu Z.-Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:3253. doi: 10.1039/C2CS35445D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang K. Hu F. Zhang Y. Wang J. Sci. China: Chem. 2015;58:1252. doi: 10.1007/s11426-015-5362-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (f) Colby D. A. Tsai A. S. Bergman R. G. Ellman J. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:814. doi: 10.1021/ar200190g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liu B. Yang L. Li P. Wang F. Li X. Org. Chem. Front. 2021;8:1085–1101. doi: 10.1039/D0QO01159B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (h) Zhang J. Lu X. Shen C. Xu L. Ding L. Zhong G. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:3263–3314. doi: 10.1039/D0CS00447B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Ali W. Prakash G. Maiti D. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:2735–2759. doi: 10.1039/D0SC05555G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews: ; (a) Sarkar S. De. Liu W. S. Kozhushkov I. Ackermann L. Weakly Coordinating Directing Groups for Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Activation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:1461–1479. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201400110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arockiam P. B. Bruneau C. Dixneuf P. H. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Activation and Functionalization. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:5879–5918. doi: 10.1021/cr300153j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ackermann L. Vicente R. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Direct Arylations through C–H Bond Cleavages. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010;292:211–229. doi: 10.1007/128_2009_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected Ru-catalyzed oxidative Heck reactions: ; (a) Weissman H. Song X. Milstein D. Ru-Catalyzed Oxidative Coupling of Arenes with Olefins Using O2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:337–338. doi: 10.1021/ja003361n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Farrington E. J. Brown J. M. Barnard C. F. J. Rowsell E. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Oxidative Heck Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:169–171. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<169::AID-ANIE169>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kwon K.-H. Lee D. W. Yi C. S. Chelate-Assisted Oxidative Coupling Reaction of Arylamides and Unactivated Alkenes: Mechanistic Evidence for Vinyl C–H Bond Activation Promoted by an Electrophilic Ruthenium Hydride Catalyst. Organometallics. 2010;29:5748–5750. doi: 10.1021/om100764c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ackermann L. Pospech J. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Oxidative C–H Bond Alkenylations in Water: Expedient Synthesis of Annulated Lactones. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4153–4155. doi: 10.1021/ol201563r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Manikandana R. Jeganmohan M. Recent Advances in the Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Chelation-Assisted C–H Olefination of Substituted Aromatics, Alkenes and Heteroaromatics with Alkenes via the Deprotonation pathway. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:8931–8947. doi: 10.1039/C7CC03213G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Li B. Devaraj K. Darcel C. Dixneuf P. Ruthenium(II) Catalysed Synthesis of Unsaturated Oxazolines via Arene C–H Bond Alkenylation. Green Chem. 2012;14:2706–2709. doi: 10.1039/C2GC36111F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kozhushkov S. I. Ackermann L. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Direct Oxidative Alkenylation of Arenes through Twofold C–H Bond Functionalization. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:886–896. doi: 10.1039/C2SC21524A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (h) Shambhavi C. N. Jeganmohan M. Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Redox-Neutral C–H Alkylation of Arylamides with Unactivated Olefins. Org. Lett. 2021;23:4849–4854. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Bechtoldt A. Baumert M. E. Vaccaro L. Ackermann L. Ruthenium(II) Oxidase Catalysis for C–H Alkenylations in Biomass-derived γ-valerolactone. Green Chem. 2018;20:398–402. doi: 10.1039/C7GC03353B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (j) Bechtoldt A. Tirler C. Raghuvanshi K. Warratz S. Kornhaass C. Ackermann L. Ruthenium Oxidase Catalysis for Site-Selective C–H Alkenylations with Ambient O2 as the Sole Oxidant. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:264–267. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Li X. Hu X. Liu Z. Yang J. Mei B. Dong Y. Liu G. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Selectively Oxidative C–H Alkenylation of N-Acylated Aryl Sulfonamides by Using Molecular Oxygen as an Oxidant. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:5916–5926. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c00242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Trita A. S. Biafora A. Drapeau M. P. Weber P. Gooßen L. J. Regiospecific ortho-C–H Allylation of Benzoic Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57:14580–14584. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Li X. Rao J. Ouyang W. Chen Q. Cai N. Lu Y.-J. Huo Y. Sequential C–H and C–C Bond Cleavage: Divergent Constructions of Fused N-Heterocycles via Tunable Cascade. ACS Catal. 2019;9:8749–8756. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b03091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ouyang W. Cai X. Chen X. Wang J. Rao J. Gao Y. Huo Y. Chen Q. Li X. Sequential C–H Activation Enabled Expedient Delivery of Polyfunctional Arenes. Chem. Commun. 2021;57:8075–8078. doi: 10.1039/D1CC03243G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu B. Ouyang W. Nie J. Gao Y. Feng K. Huo Y. Chen Q. Li X. Weak Coordinated Nitrogen Functionality Enabled Regioselective C–H Alkynylation via Pd(II)/Mono-N-Protected Amino Acid Catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:11255–11258. doi: 10.1039/D0CC04739B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu B. Rao J. Liu W. Gao Y. Huo Y. Chen Q. Li X. Ligand-Assisted Olefin-Switched Divergent Oxidative Heck Cascade with Molecular Oxygen Enabled by Self-Assembled Imines. Org. Chem. Front. 2023;10:2128–2137. doi: 10.1039/D3QO00316G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples: ; (a) Yu D.-G. Suri M. Glorius F. RhIII/CuII-Cocatalyzed Synthesis of 1H-Indazoles through C–H Amidation and N–N Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8802–8805. doi: 10.1021/ja4033555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang X. Jin X. Wang C. Manganese-Catalyzed ortho-C–H Alkenylation of Aromatic N–H Imidates with Alkynes: Versatile Access to Mono-Alkenylated Aromatic Nitriles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016;358:2436–2442. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201600128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang X. Jiao N. Rh-and Cu-cocatalyzed aerobic oxidative approach to quinazolines via [4+ 2] C–H annulation with alkyl azides. Org. Lett. 2016;18:2150–2153. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lv N. Chen Z. Liu Y. Liu Z. Zhang Y. Synthesis of Functionalized Indenones via Rh-Catalyzed C–H Activation Cascade Reaction. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2588–2591. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wu X. Xiong H. Sun S. Cheng J. Rhodium-Catalyzed Relay Carbenoid Functionalization of Aromatic C–H Bonds toward Fused Heteroarenes. Org. Lett. 2018;20:1396–1399. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang X. Lerchen A. Glorius F. A comparative investigation: group 9 Cp*M(III)-catalyzed Formal [4+ 2] Cycloaddition as an Atom-Economic Approach to Quinazolines. Org. Lett. 2016;18:2090–2093. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Jiang B. Wu S. Zeng J. Yang X. Controllable Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Arylation and Dealcoholization: Access to Biphenyl-2-carbonitriles and Biphenyl-2-carbimidates. Org. Lett. 2018;20:6573–6577. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yu S. Tang G. Li Y. Zhou X. Lan Y. Li X. Anthranil: An Aminating Reagent Leading to Bifunctionality for Both C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H under Rhodium(III) Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:8696–8700. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Kong W.-J. Finger L. H. Messinis A. M. Kuniyil R. Oliveira J. C. A. Ackermann L. Flow Rhodaelectro-Catalyzed Alkyne Annulations by Versatile C–H Activation: Mechanistic Support for Rhodium(III/IV) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:17198–17206. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on the oxidative Heck reaction of C-H bonds with allylic alcohols: ; (a) Huang L. Wang Q. Qi J. Wu X. Huang K. Jiang H. Rh(III)-Catalyzed ortho-Oxidative Alkylation of Unactivated Arenes with Allylic Alcohols. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:2665–2669. doi: 10.1039/C3SC50630D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Qi J. Huang L. Wang Z. Jiang H. Ruthenium- and Rhodium-Catalyzed Oxidative Alkylation of C–H Bonds: Efficient Access to β-Aryl Ketones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:8009–8013. doi: 10.1039/C3OB41590B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shi Z. Boultadakis-Arapinis M. Glorius F. Rh(III)-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Alkylation of (Hetero)arenes with Allylic Alcohols, Allowing Aldol Condensation to Indenes. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6489–6491. doi: 10.1039/C3CC43903H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews and examples: ; (a) Huang H. Ji X. Wu W. Jiang H. Transition Metal-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization of N-Oxyenamine Internal Oxidants. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1155–1171. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00288A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Patureau F. W. Glorius F. Oxidizing Directing Groups Enable Efficient and Innovative C–H Activation Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:1977–1979. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Neely J. M. Rovis T. Rh(III)-Catalyzed Regioselective Synthesis of Pyridines from Alkenes and α, β-Unsaturated Oxime Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:66–69. doi: 10.1021/ja3104389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Neely J. M. Rovis T. Rh(III)-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Coupling of Acrylic Acids with Unsaturated Oxime Esters: Carboxylic Acids Serve as Traceless Activators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:2735–2738. doi: 10.1021/ja412444d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Romanov-Michailidis F. Sedillo K. F. Neely J. M. Rovis T. Expedient Access to 2,3-Dihydropyridines from Unsaturated Oximes by Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:8892–8895. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lee S. Semakul N. Rovis T. Direct Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis of δ-Lactams from Acrylamides and Unactivated Alkenes Initiated by RhIII-Catalyzed C–H Activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:4965–4969. doi: 10.1002/anie.201916332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Luo A. Bao Y. Liu X. Liu J. Han W. Yang G. Yang Y. Bin Z. You J. Unlocking Structurally Nontraditional Naphthyridine-Based Electron-Transporting Materials with C–H Activation–Annulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:6240–6251. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c14297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Engle K. M. Mei T.-S. Wasa M. Yu J.-Q. Weak Coordination as Powerful Means for Developing Broadly Useful C-H Functionalization Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:788–802. doi: 10.1021/ar200185g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang Y.-F. Hong X. Yu J.-Q. Houk K. N. Experimental-Computational Synergy for Selective Pd(II)-Catalyzed C–H Activations of Aryl and Alkyl Groups. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:2853–2860. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shao Q. Wu K. Zhuang Z. Qian S. Yu J.-Q. From Pd(OAc)2 to Chiral Catalysts: The Discovery and Development of Bifunctional Mono-N-Protected Amino Acid Ligands for Diverse C–H Functionalization Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:833–851. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Neufeldt S. R. Sanford M. S. Controlling Site Selectivity in Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Bond Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:936–946. doi: 10.1021/ar300014f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang Z. Dong G. Site-Selectivity Control in Organic Reactions: A Quest To Differentiate Reactivity among the Same Kind of Functional Groups. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:465–471. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartwig J. F. Larsen M. A. Undirected, Homogeneous C–H Bond Functionalization: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016;2:281–292. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Brückl T. Baxter R. D. Ishihara Y. Baran P. S. Innate and Guided C–H Functionalization Logic. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:826–839. doi: 10.1021/ar200194b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) He J. Wasa M. Chan K. S. L. Shao Q. Yu J.-Q. Palladium-Catalyzed Transformations of Alkyl C–H Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:8754–8786. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Shan G. Yang X. Ma L. Rao Y. Pd-Catalyzed C–H Oxygenation with TFA/TFAA: Expedient Access to Oxygen-Containing Heterocycles and Late-Stage Drug Modification. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:13070–13074. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lapointe D. Markiewicz T. Whipp C. J. Toderian A. Fagnou K. Predictable and Site-Selective Functionalization of Poly(hetero)arene Compounds by Palladium Catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:749–759. doi: 10.1021/jo102081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Desai L. V. Stowers K. J. Sanford M. S. Insights into Directing Group Ability in Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Bond Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13285–13293. doi: 10.1021/ja8045519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K. Lam N. Strassfeld D. A. Fan Z. Qiao J. X. Liu T. Stamos D. Yu J.-Q. Palladium (II)-Catalyzed C–H Activation with Bifunctional Ligands: From Curiosity to Industrialization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024:e202400509. doi: 10.1002/anie.202400509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the ESI.†