Abstract

Zymoseptoria tritici is an ascomycete fungus and the causal agent of Septoria tritici leaf blotch (STB) in wheat. Z. tritici secretes an array of effector proteins that are likely to facilitate host infection, colonisation and pycnidia production. In this study we demonstrate a role for Zt-11 as a Z. tritici effector during disease progression. Zt-11 is upregulated during the transition of the pathogen from the biotrophic to necrotrophic phase of wheat infection. Deletion of Zt-11 delayed disease development in wheat, reducing the number and size of pycnidia, as well as the number of macropycnidiospores produced by Z. tritici. This delayed disease development by the ΔZt-11 mutants was accompanied by a lower induction of PR genes in wheat, when compared to infection with wildtype Z. tritici. Overall, these data suggest that Zt-11 plays a role in Z. tritici aggressiveness and STB disease progression possibly via a salicylic acid associated pathway.

Introduction

The fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici is the causal agent of Septoria tritici blotch (STB) disease in wheat, which causes on average, yield losses of around 20% on susceptible wheat cultivars in North-Western Europe [1]. Due to the rapid emergence of fungicide tolerance and evolution of virulence against resistant wheat cultivars, Z. tritici poses a threat to wheat production worldwide [2].

Successful plant colonization by filamentous plant pathogens is dependent on the ability of the pathogen to overcome host defences. This manipulation of host defence is achieved through the secretion of a repertoire of effector proteins [3, 4]. These effector proteins are typically small, secreted proteins (SSPs) that facilitate suppression of host cellular defence and/or protection from antimicrobial proteins [5]. Z. tritici secretes SSPs that play a role in virulence and aggressiveness [6–9]. For example, two lysin motif containing effectors; Mg3LysM and Mg1LysM play an important role in protection of the fungal cell wall of Z. tritici against host chitinases through chitin sequestration [10, 11]. Zt80707 is a secreted protein under positive selection that contributes to Z. tritici virulence [12]. Previously we found a conserved effector ZtSSP2, that can interact with a wheat host E3 ubiquitin ligase (TaE3UBQ) to promote STB infection [9].

Plants have also evolved receptors that can recognise some of these effectors and thus confer resistance to invading pathogens [13, 14]. Studies utilising association genetic mapping identified the Z. tritici effector gene AvrStb6 [15]. The Z. tritici effector AvrStb6 is recognised by wheat cultivars carrying the corresponding resistance gene, Stb6 which encodes a wall associated kinase [16]. The recently cloned resistance gene Stb16q provides broad spectrum resistance and encodes a cysteine rich receptor-like kinase (CRK) which recognises the avirulence gene product AvrStb16q [17]. While Stb15 which recognises AvrStb15, is a lectin receptor-like kinase [18]. Finally, Avr3D1 is recognised by wheat cultivars carrying the resistance gene Stb7 [19].

In this study, we show a role for the Z. tritici effector protein; Zt-11 in disease development. Zt-11 is a small (79 amino acid), cysteine rich (10 cysteine residues) secreted protein located on core chromosome 5 [7]. It was previously found to interact with the wheat secreted proteins TaSRTRG6 (Triticum aestivum Septoria Responsive Taxonomically Restricted Gene 6) [20], TaSSP6 and TaSSP7 [21]. Zt-11 appears to be specific to Z. tritici and since it interacts with several host defence proteins, one of which (TaSRTG6) is taxonomically restricted, we studied Zt-11 further to investigate a potential role in the Z. tritici-wheat interaction. Zt-11 expression peaks at the transition from the biotrophic to the necrotrophic phase of STB infection. Using a targeted gene replacement approach to knockout Zt-11 we demonstrate its role in the timing of aggressiveness, disease development and asexual sporulation of Z. tritici which is associated with salicylic acid (SA) related gene expression.

Materials and methods

Plant material and fungal strains

The susceptible wheat cultivar Longbow was used throughout this study. Plastic trays containing John Innes Compost No. 2 (Westland Horticulture, UK) were sown with 10–12 wheat seeds. The wheat plants were grown in a growth chamber at 16 hours day/8-hour night photoperiod at 13,000 lux, RH 80% ± 5% at 19°C/20°C.

Cultures of Z. tritici IPO323 [22] were grown on Yeast Peptone Dextrose Agar (YPDA) (yeast extract 10 g/l, peptone 20 g/l, glucose 20 g/L and technical agar 20 g/L) or Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) (potato dextrose broth 24 g/L, technical agar 20 g/L) for five to six days in a growth cabinet with a temperature of 20 °C and 16:8 light/dark cycles. For in vitro phenotyping fungal strains were grown in Yeast extract glucose agar (YEG) (1% Yeast extract, 2% glucose and 2% Agar) medium supplemented with H2O2 at concentrations 0, 2, 4 and 6mM and the plates were incubated for 7 days at 20°C.

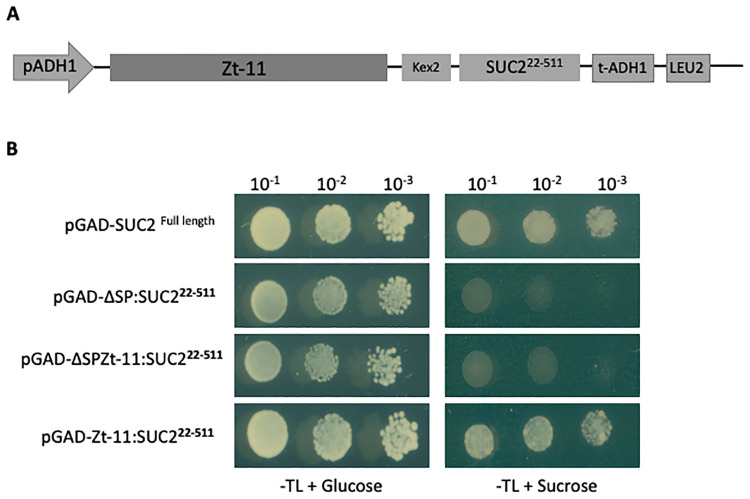

Validation of protein secretion using a yeast sucrose secretion system

A Gateway-compatible vector (pGADT7) for yeast secretion assay and suc2 yeast mutant (strain SEY6210) was utilized [20, 21]. Briefly, the invertase (SUC2) gene with and without signal peptide was amplified from the yeast strain BY4741 with a linker (Kex2 site) added between the Gateway reading frame and the SUC2 gene. This construct was ligated into the pGADT7 vector and verified by sequencing. Candidate Zt-11 and ΔSP-Zt-11 were cloned into the yeast secretion vector in-frame with the N-terminus of the SUC gene and transformed into the suc2 yeast mutant. Transformants were PCR validated using primers listed on S1 Table and selected on a synthetic dropout medium (minus Trp and Leu) with sucrose as a sole carbon source. Yeast spotting was performed with dilutions of 10−1, 10−2, and 10−3 respectively. The experiment was repeated twice independently with four replicates per independent experiment.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

For the Zt-11 gene expression studies, 14 day-old wheat leaves infected with Z. tritici IPO323 were collected at 0, 4, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17 and 21 days post-infection (dpi). Each sample consisted of 100mg pooled from two individual leaves from each seedling. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C. The experiment was repeated three times independently.

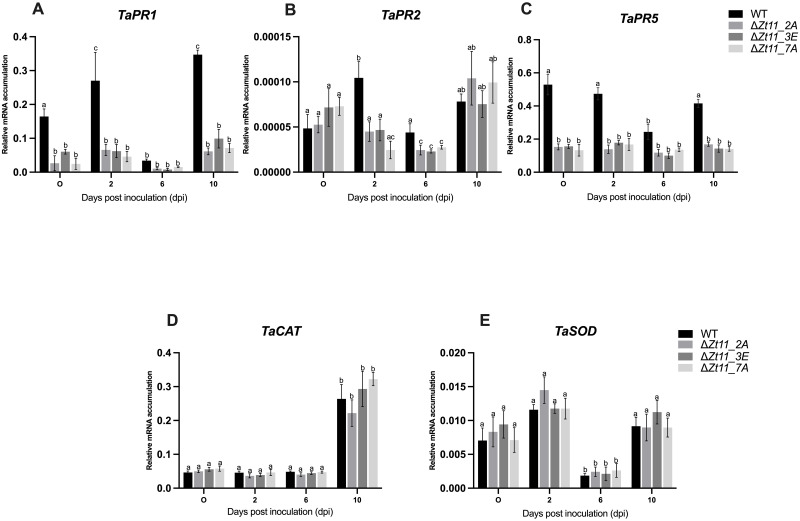

For plant defence gene expression, 14 days old wheat leaves were infected with either wild type strain (IPO323) or KO strains (designated ΔZt11_2B, ΔZt11_3E and ΔZt11_7A). Sampling was carried out at 0, 2, 6 and 10 days post inoculation (dpi). All samples (100mg) were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Defense marker genes were analyzed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) with primers for the following: pathogenesis-related (PR) genes TaPR1, TaPR2, and TaPR5; superoxide dismutase (TaSOD) and catalase (TaCAT). Primers are listed in S1 Table. Two independent experiments were carried out. Each experiment included three leaves each from three plants per strain per time point (n = 6).

Total RNA was extracted from Z. tritici-infected wheat leaves or YPDA cultures using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was then subjected to on-column DNase treatment (Sigma). Quantification of total RNA was carried out using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Reverse transcription of 1–2 μg of RNA for cDNA synthesis was carried out using the Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen).

Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out in 12.5 μl reactions including 1.25 μl of a 1:5 (v/v) dilution of cDNA, 0.2 μM of primers, and 1×SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Tli RNase H plus, RR420A; Takara). PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 1 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 20 s at 60 °C; and a final cycle of 1 min at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 30 s at 95 °C for the dissociation curve. qPCR was performed using the QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and the relative gene expression was calculated as 2^−(Ct target gene–Ct housekeeping gene) as previously described [23]. The Z. tritici β-tubulin gene [8] was used as reference gene for the Zt-11 time course. Wheat glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (TaGAPDH) was used as a reference gene for defence gene quantification. Average Ct and SEM values were calculated from six individual Ct values per strain per time point.

Construct generation

The gene deletion construct for Zt-11 was constructed using a yeast-based homologous recombination as described by Tiley et al. [24] Primers for plasmid construction are listed in S1 Table. Briefly, the 1.5 kb upstream and downstream flanking region was selected for the effector gene candidate Zt-11 (Mycgr3G104444), based on the reference genome database available for Z. tritici IPO323 available at JGI [25]. Yeast based homologous recombination was utilized for knockout (KO) plasmid construct using the pCAMBIA0380_YA (yeast-adapted) vector as a backbone, Hygromycin-trpC resistance cassette from pCB1003 [26] flanked by two 1.5 kb regions targeting the Zt-11 locus. The flanking regions and Hygromycin-trpC resistance cassette were amplified using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and successive PCR product purification.

A Zymoprep™ Yeast Plasmid Miniprep II kit (Zymo Research) was used to recover plasmid DNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, propagated into Escherichia coli DH5α cells and isolated using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or Gene JET Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Correct plasmid assembly was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation

The ΔZt-11 knockout vector was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA1126 and AGL1 cells. Agrobacterium–mediated transformation was then used to transform the Z. tritici IPO323 strain following the protocol outlined in Derbyshire et al. [27, 28].

Confirmation of ΔZt-11 strains

Following 10–14 days after transformation separate Z. tritici transformants were selected and transferred to YPDA (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose, and 20 g/L technical agar) supplemented with Hygromycin B (100 μg/ml) and Timentin™ (100 μg/ml). Potential mutants were then sub-cultured at least three times to acquire a pure culture. Double PCR was carried out on the Z. tritici genomic DNA extracted with the sonication method [29] using two primer pairs; the first primer pair (Fwd_Zt11_WT and Rvs_Zt11_WT) was designed to amplify the wild-type gene, and the second pair (Fwd_Hyg and Rvs_Hyg) to amplify the Hygromycin-trpC resistance cassette (S1 Fig). We further confirmed the deletion of Zt-11 gene by sequencing the insertions region (flanking regions and hygromycin insert) on all three independent KO strains (ΔZt11_2B, ΔZt11_3E and ΔZt11_7A) (S2 Fig). Complementation of the mutants was unsuccessful; thus, an ectopic strain was selected in order to validate the mutants. In the ectopic strain both bands are present due to the insertion of the Hygromycin-trpC resistance cassette in other genome coordinates with no deletion of the Zt-11 gene. Primers used for knockout confirmation and sequencing are listed in S1 Table.

In planta experiments

For plant infections, the Z. tritici IPO323, ectopic and three independent KO strains (designated ΔZt11_2B, ΔZt11_3E and ΔZt11_7A) were cultured onto YPDA and grown at 20°C under white light supplemented with blue/black ultraviolet (UV-A) light under a 12:12 hour light:dark photo cycle for approximately 7 days to achieve yeast-like growth of fungal isolates [24]. Fungal spores from the YPDA cultures were carefully harvested using an inoculating T-shaped spreader and suspended in deionised sterile water. Spore concentrations were adjusted to 1x10⁶ ml-1 in deionised sterile water containing 0.01% Tween20 solution. A spore suspension of 20 ml per plant tray was sprayed using plastic hand-held spray bottles. Control plants were sprayed with 20 ml of deionised sterile water containing 0.01% Tween20. The first true leaf of the wheat cv. Longbow was held adaxial side up on polystyrene blocks for inoculation [30]. Wheat seedlings were inoculated at 14 days old. At least 10–12 seedlings were potted in each tray for each strain per independent experiment. Inoculated plants were then covered with polythene bags for 72 h to ensure high humidity. Four independent experiments were carried out n ≥ 40 plants per strain.

Virulence and aggressiveness of Z. tritici ΔZt-11 strains, IPO323 and the ectopic strain was assessed by monitoring and recording disease progression from the appearance of the first symptoms at 8 dpi. Disease symptoms on the infected leaves were scored from 1 to 5 by eye using a modified version of the scale from Skinner [31]. Briefly, the scale measurement was as follows: 1 representing no disease symptoms, 2 representing small chlorotic flecks, 3 representing chlorosis, 4 representing necrosis and lastly 5 representing necrosis with pycnidia.

Pycnidia and pycnidiospore production

Pycnidia production was analysed for each strain at 21 dpi. A total of ten leaves were sampled from each strain for four independent experiments (n = 40 per strain). Leaves were scanned (1200 dots per inch) using an Epson Perfection V600 Photo Scanner and analysed by ImageJ [32] with an automated technique protocol [33, 34]. Each leaf was designated a QR code and following parameters were automatically recorded from the scanned image: total leaf area, necrotic and chlorotic leaf area, number of pycnidia, and their positions on the leaf. Pycnidia production per centimetre square of leaf was calculated for the IPO323, ectopic, and ΔZt-11 strains.

The same leaves which were used for pycnidia production were then used to calculate the number of pycnidiospores. Six centimetres from each leaf, for a total of ten leaves for each strain (n = 40), were placed in a petri dish in high humidity for 48h at room temperature (20 ± 3°C). Each leaf was then suspended in 2 ml of sterile distilled water and vortexed for 5 seconds. Suspended macro pycnidiospores and micropycnidiospores were counted with a haemocytometer per each leaf and recorded [24]. Four independent experiments were carried out.

For pycnidia size measurements, two leaves from two plants per isolate at 21 dpi were harvested and stained with trypan blue. The leaf sections were then mounted with Polyvinyl Alcohol-Lactic acid (PVA-L) medium (8% v/v) microscopy glue and observed under light microscope (Leica DM5500B). Pycnidia width was calculated using the custom scale bar in Leica DM5500B microscope. This experiment was conducted twice independently with at least 100 pycnidia counted per leaf per plant.

Results

Zt-11 is a small, secreted protein specific to Z. tritici

Eight Z. tritici SSPs were previously shown to interact with wheat proteins that play a role in defence against Z. tritici [20, 21]. We conducted a BLASTP search to identify any potential homologues of these eight Z. tritici SSPs (S2 Table). Two SSPs from Z. tritici (Zt-11 and Zt-26) out of the eight lacked hits in any fungal species except Z. tritici (S2 Table).

Zt-11 is predicted to have a N-terminal signal peptide (0.9978 likelihood, SignalP-5.0) [35]. The secretion signal was validated using a yeast secretion assay (Fig 1A) [20, 21]. The full length Zt-11 construct was able to complement the suc2 knockout yeast strain, thus allowing the yeast cells to grow in selection media containing sucrose as the sole source of carbon (Fig 1B). No conserved domains were found for Zt-11 using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (NCBI CDD) [36].

Fig 1. Zt-11 is a secreted protein.

(A) Design of the gateway compatible yeast pGADT7-Zt-11-Suc2 vector and Invertase mutant yeast strain SEY6210 used for the secretion assay [20]. (B) Yeast strains carrying Zt-11 with secretion signal fused in frame with the Invertase gene Suc2 were able to grow in sucrose containing drop out media (SD-TL) sucrose therefore cells will grow if Invertase is secreted. SEY6210 carrying the pGAD-ΔSP:SUC222-511 vector was used as negative control while SEY6210 with pGAD-SUC2Full length acts as positive control. This experiment was repeated twice independently with four replicates per construct in each experiment.

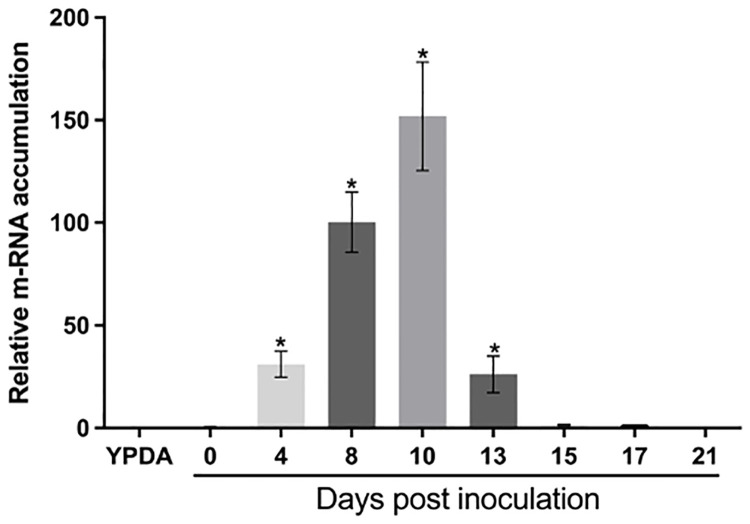

The timing of Zt-11 expression during infection of wheat was investigated using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). During wheat infection, Zt-11 was significantly upregulated (P < 0.01) from 4 dpi to 10 dpi compared to 0 dpi, with a peak of expression at 10 dpi. At the later necrotrophic phase of infection (15–21 dpi) Zt-11 expression was downregulated with low expression levels similar to those found at 0 dpi. Zt-11 was expressed at low levels in vitro compared to in planta conditions (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Zt-11 expression during Z. tritici infection.

Transcript levels of Zt-11 during in vitro (YPDA) compared with in planta infection of wheat at 0, 4, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17 and 21 days post inoculation (dpi) (cv. Longbow) with Z. tritici (IPO323). The expression levels of β-tubulin (Z. tritici) were used to normalize the expression levels of Zt-11. Each independent experiment had two leaves each from two individual plants. Three independent experiments were performed. The bars represent the mean relative expression ± SEM. Asterisk above bars indicate significant differences compared to 0 dpi, as determined by Tukey’s test (P < 0.01).

ΔZt-11 strains show delayed disease development

To understand whether Zt-11 plays a role in Z. tritici virulence and aggressiveness, we generated Zt-11 deletion strains using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (S1A Fig). Successful transformation was indicated by loss of the wild-type Zt-11 and the gain of the knockout (KO) fragment (S1B Fig). Additionally, Zt-11 deletion strains were also confirmed by amplicon sequencing (S2 Fig). Three independent deletion strains (ΔZt-11_2B, ΔZt-11_3E and ΔZt-11_7A) and an ectopic strain were selected.

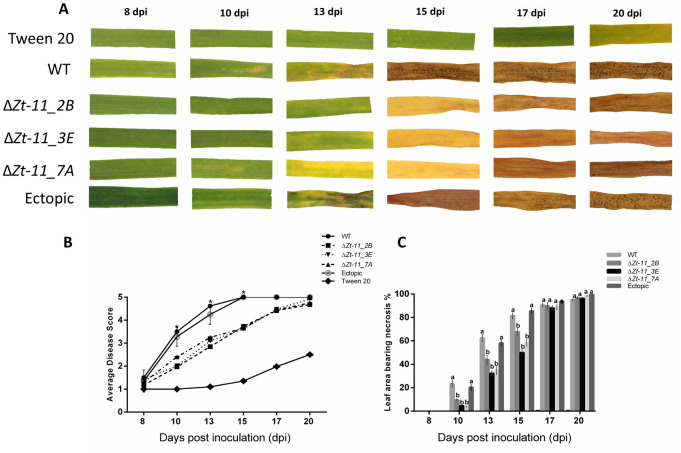

The parental IPO323 wild-type (WT) strain, the KO strains ΔZt-11_2B, ΔZt-11_3E and ΔZt-11_7A and ectopic strain were subsequently inoculated onto leaves of the susceptible wheat cultivar Longbow. Disease progression was monitored from 3 dpi and recorded from 8 dpi when the first signs of disease symptoms were observed. The first symptoms of disease were visible as small chlorotic lesions observed on leaves infected with the IPO323 and ectopic strain at 10 dpi (Fig 3A). The chlorotic lesions developed into necrotic lesions with pycnidia, visible from 13–15 dpi on leaves infected with IPO323 and the ectopic strain (Fig 3A). However, the leaves infected with ΔZt-11 strains developed chlorotic lesions only from 13 dpi, followed by necrosis and pycnidia production from 17 dpi (Fig 3A). Overall, the timing of symptom appearance for the ΔZt-11 strains was significantly delayed (P < 0.01) with lower disease scores at 10, 13 and 15 dpi compared to IPO323 and the ectopic strain (Fig 3B).

Fig 3. ΔZt-11 mutant strains show delayed disease development.

(A) Disease development of ΔZt-11 mutant on the susceptible wheat cv. Longbow compared to IPO323 and ectopic strain. Images are representative of four independent experiments (n ≥ 40). At least 10 leaves each from an individual plant per experiment were analysed. (B) Disease progression of wheat infected with Z. tritici ΔZt-11 mutant strains compared with IPO323 and the ectopic strain from 8 dpi to 20 dpi based on the 1 to 5 scale [31]. Each data point represents the average of four independent experiments, with at least 10 leaves per experiment per strain, each from an individual plant (n ≥ 40). Asterisks represent significant differences between the IPO323 strain and mutants (ΔZt-11_2B, ΔZt- 11_3E and ΔZt-11_7A) at P < 0.01, according to Mann-Whitney-U-test test. (C) Necrosis percentage of wheat cv. Longbow leaves infected with ΔZt-11 mutant strains compared with the IPO323 and ectopic strain from 8 dpi to 20 dpi. Bar chart showing necrosis progression with each data point represents the average of four independent experiments with at least 10 leaves each from an individual plant per experiment per isolate (n ≥ 40). Error bars are +/- SEM of the mean. Different letters indicate significant differences between each other (Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.01).

To further investigate the delayed disease symptoms displayed by leaves infected with the ΔZt-11 strains, we used percentage leaf area bearing necrosis as an additional disease index (Fig 3C). A significant reduction (P < 0.01) in the percentage of leaf area covered in necrosis was observed for the ΔZt-11 strains at 10, 13 and 15 dpi when compared to IPO323 and the ectopic strain (Fig 3C). However, from 17 dpi onwards there were no significant differences in necrosis between ΔZt-11 strains with the ectopic strain as well as IPO323.

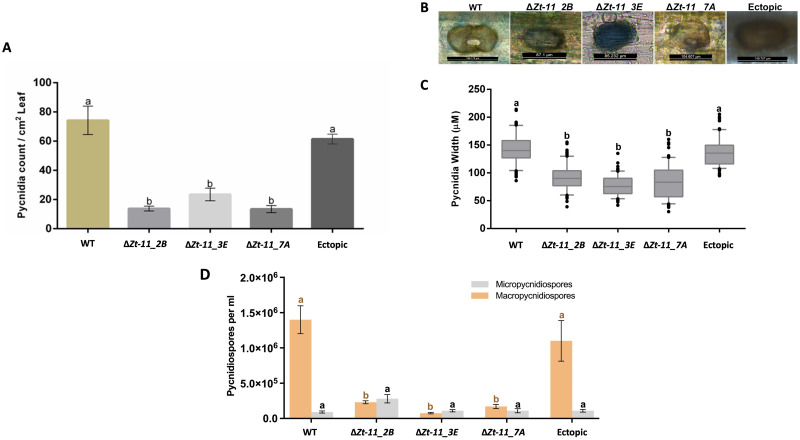

Deletion of Zt-11 impacts asexual sporulation

Further analysis was performed to determine if Zt-11 impacts pycnidia production. We measured pycnidia density on infected leaves [34]. At 21 dpi, the number of pycnidia on each leaf of the ΔZt-11 strains was determined and compared to the IPO323 strain (Fig 4A). The ΔZt-11 strains produced a significantly smaller number (P < 0.01) of pycnidia, in comparison to IPO323 and the ectopic strain. On average the mutants produced significantly less pycnidia compared to leaves infected with IPO323 and the ectopic strain (Fig 4A). In addition to differences in the number of pycnidia produced by the ΔZt-11 strains, we also measured the pycnidia size (Fig 4B and 4C) and found that ΔZt-11 strains produced significantly smaller pycnidia (P < 0.01) compared to the IPO323 and ectopic strain (Fig 4B and 4C). We found no significant differences in pycnidia production between the ectopic strain and IPO323.

Fig 4. Deletion of Zt-11 impacts asexual sporulation.

(A) ΔZt-11 mutants produced significantly fewer pycnidia compared to the IPO323 and ectopic strain. Inoculated leaves were scanned at 21 dpi and scanned images were analysed to obtain the number of pycnidia with the software Image J. Each data point represents the average of four independent experiments with at least 10 leaves per experiment per strain, each from an individual plant (n ≥ 40). (B) Representative images of Pycnidia size between the IPO323, ectopic and ΔZt-11 mutant strains. (C) Comparison of pycnidia size between IPO323, ectopic and Zt-11 mutant strains. For pycnidia size measurement, two leaves from two plants per isolate at 21 dpi were taken and stained with trypan blue and at least 100 pycnidia were counted per leaf using a light microscope (Leica DM5500B). Pycnidia width was calculated using the scale bar. The experiment was conducted twice independently. Error bars are +/- SEM of the mean. Different letters indicate significant differences between each other (Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.01). (D) Stacked bar chart showing macropycnidiospores and micropycnidiospores counts per ml at 21 dpi (Leaf = 6cm). ΔZt-11 mutants produced significantly lower macropycnidiospores numbers (indicated by different letters) but not fewer micropycnidiospores when compared to the IPO323 and ectopic strain. Each data point represents the average of four independent experiments, 10 leaves per experiment per strain, each from an individual plant (n ≥ 40). Different letters indicate significant differences between each other (Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.01).

The ΔZt-11 strains were able to exude cirrhus containing pycnidiospores (S3 Fig). The asexual spores produced by Z. tritici fall into two categories: macropycnidiospores, and micropycnidiospores [37, 38]. Since Zt-11 impacted pycnidia number and size we assessed the types of pycnidiospores produced. The number of macropycnidiospores and micropycnidiospores in the ΔZt-11 strains were counted and compared to IPO323 and the ectopic strain (Fig 4D). Macropycnidiospores production was significantly lower (80 ± 10%, P < 0.01) in leaves infected with the ΔZt-11 strains compared to IPO323 and the ectopic strain (Fig 4D). While, the number of micropycnidiospores produced was not significantly different between strains (Fig 4D).

ΔZt-11 strains lead to lower induction of host SA mediated defence genes during infection

To further determine whether delayed disease development by the mutant strains were due to changes in host defense gene related transcripts, qRT-PCR was used to examine the levels of wheat pathogenesis-related genes namely; TaPR1, TaPR2 and TaPR5 as markers of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in plants (Fig 5A–5C) [39–41] and two reactive oxygen species (ROS) related wheat genes Catalase (TaCAT) and Superoxide dismutase (TaSOD) (Fig 5D and 5E). The wheat plants infected with the Z. tritici strain IPO323 showed early induction of TaPR1 and TaPR5 at 2 dpi and also had significantly higher transcript accumulation of TaPR1 at 10 dpi compared to 0 dpi. The levels of TaPR1, TaPR2 and TaPR5 were significantly lower in wheat infected with the ΔZt-11 mutant strains than IPO323 at all timepoints with the exception of TaPR2 at 0 dpi and 10 dpi and TaPR1 at 6 dpi (Fig 5A–5C). The levels of TaCAT were significantly upregulated at 10 dpi compared to 0, 2 and 6 dpi for all Z. tritici strains. TaSOD was downregulated at 6 dpi compared to 0, 2 and 10 dpi for all Z. tritici strains. However, the transcript level of ROS scavenging genes TaSOD and TaCAT were not significantly different in infected wheat leaves between IPO323 or ΔZt-11 mutant strains (Fig 5D and 5E). We investigated the vegetative growth of the ΔZt-11 mutants on solid media (PDA and YEG) to determine the impact of H2O2 (2, 4 and 6 mM) on the ΔZt-11 mutants compared to IPO323. In line with no differences in antioxidant (TaSOD and TaCAT) gene expression between IPO323 and the ΔZt-11 strains, we observed no differences in vegetative growth, melanisation, nor in resistance/susceptibility to H2O2 between IPO323 and ΔZt-11 mutants (S4 Fig).

Fig 5. Transcript profile of wheat defence genes in wheat samples infected with the ΔZt-11 mutant strain compared with IPO323.

(A) TaPR1, (B)TaPR2, (C) TaPR5, (D) TaCAT and (E) TaSOD. The results represent the mean of three leaves (each from individual plants) per strain per time point over two independent experiments (n = 6) (error bars indicate ±SEM). Relative gene quantification was calculated by the comparative 2^-ΔCT method [23]. Normalization was carried out using wheat glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Different letters indicate significant differences between each other as determined using Tukey’s HSD test. (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Z. tritici is known to secrete an abundant number of effector proteins into the wheat host apoplast during infection [7, 8, 42]. Effectors are at the frontline during plant-pathogen interactions and a diverse array of these pathogen effectors are known to interact with host targets to allow infection and host colonization [43–45]. Owing to the importance in manipulation of host processes, studies have highlighted that most pathogen effector genes are cysteine rich secreted proteins and have increased expression in host plants. This reflects their function compared to in-vitro conditions [7, 8, 46]. Zt-11 was predicted to be a secreted protein, based on the presence of N-terminus signal peptide sequence and this was validated by using a secretion assay [20, 21].

Z. tritici has been described as hemibiotroph [8] or a late necrotroph with a long latent phase [47]. We examined the expression of Zt-11 in infected wheat leaves using qRT-PCR and found that Zt-11 displayed significantly induced expression in planta from 4 dpi to 10 dpi. This expression profile of Zt-11 corresponds to the switch from the biotrophic to necrotrophic phase of Z. tritici infection. A similar expression pattern of Zt-11 was also reported previously where Zt-11 expression was low at 2 dpi peaking at 8 dpi before decreasing from 12–20 dpi [7, 46].

Our previous studies indicated that Zt-11 interacts with wheat proteins TaSRTRG6, TaSSP6 and TaSSP7 [20, 21]. These are small, secreted wheat proteins highly expressed in response to Z. tritici infection. TaSRTRG6 has homology with a Bowman-Birk type proteinase inhibitor [20]. In rice, a similar proteinase inhibitor AvrPiz-t Interacting Protein 4 (APIP4) is an effector target protected by a nucleotide-binding and leucine-rich repeat (NLR) R protein (Piz-t) [48]. TaSSP6 has significant homology to a glycine rich protein [21]. Previously, a glycine rich protein in Lily (Lilium spp.) was found to be required for resistance against the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis elliptica [49]. TaSSP7 has significant homology to a papilin-like isoform which is an extracellular matrix glycoprotein [50]. Silencing of these genes in wheat increased susceptibility to STB, confirming their role in defence against Z. tritici [20, 21]. Owing to its interaction with Z. tritici responsive wheat resistance protein, we hypothesize that Zt-11 could be an important effector protein of Z. tritici and plays a role in disease. Therefore, the contribution of Zt-11 to the virulence and aggressiveness of Z. tritici was assessed using a targeted gene replacement approach to knockout Zt-11.

In Z. tritici, only a few small secreted protein effectors such as LysM and Zt80707, when deleted show an impact on fungal virulence [10, 12]. The Z. tritici mutants with deletion of Zt-11 were able to infect wheat, however, the mutants were found to be significantly delayed in disease development from 10 dpi. This timing of significant lower disease symptoms coincides with the expression of Zt-11 during the switch from the biotrophic to necrotrophic phase suggesting that Zt-11 may support the timely progression to necrotrophy. It is possible that the slower wheat infection observed for the ΔZt-11 mutants compared to the wildtype Z. tritici strain is due to lower fungal biomass produced over time. Z. tritici growth rate can predict the latent period and pycnidia coverage [51]. We observed that ΔZt-11 strains were impaired in the development of pycnidia, producing significantly reduced numbers of pycnidia. The pycnidia of the ΔZt-11 strains were also significantly smaller in width compared with pycnidia from the IPO323 strain. This impaired pycnidia development may be a result of slower infection and lower fungal biomass produced by the ΔZt-11 mutants.

Previously, no significant difference in pathogenicity was found between a single ΔZt-11 strain and wildtype Z. tritici, following leaf infection with 1x107spores/ml at 21 dpi [52]. However, in this study significant differences in disease progression were found between three ΔZt-11 strains and wildtype Z. tritici between 10–15 dpi using 1x10⁶ spores/ml. The lower inoculum density coupled with a time course and three independent ΔZt-11 strains may explain the detection of significant differences in disease progression here compared to observation at 21 dpi only. In addition measuring pycnidia number using an automated technique coupled with microscopy led to the discovery of reduced pycnidia number and size as well as altered macropycnidiospore production in planta, all of which had not been previously assessed.

The asexual reproduction of Z. tritici comprises macropycnidiospore and micropycnidiospore production. Macropycnidiospores are curved and elongated around 35–98 μm x 1–3 μm in size with a total of 3–5 septa and micropycnidiospores are smaller 8–10.5 μm x 0.81 μm with no septa. Both spore forms can form hyphal growth, and both are able to infect wheat [37, 38, 53]. Our investigation of asexual spore types suggests that Zt-11 deletion significantly decreases macropycnidiospores numbers rather than micropycnidiospores. Production of macropycnidiospores and micropycnidiospores are regulated by different pathways in Z. tritici [38] and this suggests that Zt-11 could contribute to macropycnidiospore production. The impaired pycnidia and pycnidiospores production of the ΔZt-11 strains in our study is similar with a study reporting the impact of the deletion of the extracellular effector, Zt80707 in Z. tritici which also led to delayed pycnidia formation, lower pycnidia numbers, reduced pycnidiospores production and smaller pycnidia [12].

Previously, a single ΔZt-11 strain was observed to have longer yeast-like spores (blastopores) produced in vitro (YPD) compared to wildtype Z. tritici. However, we did not observe morphological differences in yeast-like spores between the wildtype Z. tritici strain and three independently generated ΔZt-11 mutants in vitro (YPD). In addition, we did not find impaired mycelial growth across the three ΔZt-11 mutants compared to wildtype Z. tritici on PDA or YEG. In contrast, impaired mycelial growth was previously reported for a ΔZt-11 strain grown in vitro (PDA and water agar) [52].

Rapid induction of defence-related pathogenesis-related (PR) genes are triggered in wheat against infection by Z. tritici [54–57]. We found that the expression of PR genes especially TaPR1and TaPR5 were between 0 dpi and 10 dpi in ΔZt-11-infected wheat samples compared to WT-infected samples. Similarly, TaPR2 also showed significantly lower expression in ΔZt-11-infected wheat leaves at 2 dpi and 6 dpi compared to WT-infected samples. Similar results were reported recently, where deletion strains of Z. tritici adenylate cyclase enzyme (Δztcyr1) were unable to induce activation of the wheat defence response [58]. It was found that Δztcyr1-infected samples showed down-regulation of TaPR genes [58]. Our results suggest that ΔZt-11 strains do not activate a wheat immune response, potentially due to the absence of recognition via wheat proteins TaSRTRG6, TaSSP6 and TaSSP7 (or guards thereof). There is subsequently low SA accumulation, PR gene expression and, as a result, delayed necrosis symptoms compared to WT-infected samples. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) during Z. tritici- host interactions are important for resistance to host defences [59–61]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and Catalase (CAT) are known ROS scavengers and play a key role in antioxidant defence [62, 63]. However, we did not observe any significant differences in expression of TaSOD and TaCAT between WT and ΔZt-11-infected wheat samples nor on media supplemented with H2O2. This suggests no direct role of Zt-11 in host ROS metabolism and a possible action of Zt11 independent of host ROS production.

Conclusion

In summary, our work characterized a cysteine rich Z. tritici specific effector protein Zt-11, for a role in disease. We demonstrated that Zt-11 is a pathogen secreted protein with high expression at the transition phase during infection. Zt-11 contributes to pathogen aggressiveness and timely disease progression potentially due to activation of wheat SA responses including PR genes. However, the precise molecular mechanism of how Zt-11 functions with TaSRTRG6, TaSSP6 and TaSSP7 during the Z. tritici-wheat interaction remains to be elucidated.

Supporting information

A, Diagram showing the location of the two primer pairs used to confirm successful transformation of Z. tritici. The replacement of Zt11 by the hygromycin-trpC resistance cassette through homologous recombination is depicted by dotted blue lines on the flanking regions. B, Successful disruption of the Zt11 gene in the mutants indicated by presence of the KO amplicon (2340 base pairs) and absence of the Zt11 wild-type WT amplicon (2124 base pairs). 1kb (kilobase) ladder (Bioline).

(TIF)

Each row represents sequences (left flank, hygromycin and right flank) confirmed by amplicon sequencing in the mutant strains.

(TIF)

ΔZt11 mutant strain, WT (IPO323) and ectopic strain pycnidia on wheat cv. Longbow leaves at 21 dpi. Arrows indicate the cirrhus containing pycnidiospores, scale bars representative of 50μm.

(TIF)

Approximately 107 spores/mL of spores was spotted on to three different solid growth media; PDA, YPDA and YEG (supplemented with H2O2 at concentrations 0, 2, 4 and 6mM) and incubated for 7 days at 20°C. Scale bar = 5mm. Images are representative of three independent experiments, with a total of 2 plates per experiment per media type (n = 4).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr A. Bailey, University of Bristol, UK for providing us with the pCAMBIA0380_YA vector and IPO323 strains and Prof. F. Doohan for providing wheat cultivar longbow seeds used in the experiments.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) career development award 15/CDA/3451, Strategic Partnerships Programme (16/SPP/3296) and Frontiers for the Future Programme 20/FFP-P/8545.

References

- 1.Fones H, Gurr S. The impact of Septoria tritici Blotch disease on wheat: An EU perspective. Fungal genetics and biology. 2015;79:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.004 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fones HN, Bebber DP, Chaloner TM, Kay WT, Steinberg G, Gurr SJ. Threats to global food security from emerging fungal and oomycete crop pathogens. Nature Food. 2020(6):332–42. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0075-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dou D, Zhou JM. Phytopathogen effectors subverting host immunity: different foes, similar battleground. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12(4):484–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Does HC, Rep M. Adaptation to the host environment by plant-pathogenic fungi. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 2017;55(1):427–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080516-035551 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Presti LL, Kahmann R. How filamentous plant pathogen effectors are translocated to host cells. Current opinion in plant biology. 2017;38:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morais do Amaral A, Antoniw J, Rudd JJ, Hammond-Kosack KE. Defining the predicted protein secretome of the fungal wheat leaf pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e49904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049904 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gohari AM, Ware SB, Wittenberg AH, Mehrabi R, M’Barek SB, Verstappen EC, et al. Effector discovery in the fungal wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Molecular plant pathology. 2015;16(9):931. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12251 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudd JJ, Kanyuka K, Hassani-Pak K, Derbyshire M, Andongabo A, Devonshire J, et al. Transcriptome and metabolite profiling of the infection cycle of Zymoseptoria tritici on wheat reveals a biphasic interaction with plant immunity involving differential pathogen chromosomal contributions and a variation on the hemibiotrophic lifestyle definition. Plant physiology. 2015;167(3):1158–85. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.255927 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karki SJ, Reilly A, Zhou B, Mascarello M, Burke J, Doohan F, et al. A small secreted protein from Zymoseptoria tritici interacts with a wheat E3 ubiquitin ligase to promote disease. Journal of experimental botany. 2021;72(2):733–46. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa489 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall R, Kombrink A, Motteram J, Loza-Reyes E, Lucas J, Hammond-Kosack KE, et al. Analysis of two in planta expressed LysM effector homologs from the fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola reveals novel functional properties and varying contributions to virulence on wheat. Plant physiology. 2011;156(2):756–69. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176347 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez-Vallet A, Tian H, Rodriguez-Moreno L, Valkenburg DJ, Saleem-Batcha R, Wawra S, et al. A secreted LysM effector protects fungal hyphae through chitin-dependent homodimer polymerization. PLoS Pathogens. 2020;16(6):e1008652. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008652 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poppe S, Dorsheimer L, Happel P, Stukenbrock EH. Rapidly evolving genes are key players in host specialization and virulence of the fungal wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici (Mycosphaerella graminicola). PLoS pathogens. 2015;11(7):e1005055. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005055 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. nature. 2006;444(7117):323–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05286 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Wit PJ, Mehrabi R, Van den Burg HA, Stergiopoulos I. Fungal effector proteins: past, present and future. Molecular plant pathology. 2009;10(6):735–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00591.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong Z, Marcel TC, Hartmann FE, Ma X, Plissonneau C, Zala M, et al. A small secreted protein in Zymoseptoria tritici is responsible for avirulence on wheat cultivars carrying the Stb6 resistance gene. New Phytologist. 2017;214(2):619–31. doi: 10.1111/nph.14434 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saintenac C, Lee WS, Cambon F, Rudd JJ, King RC, Marande W, et al. Wheat receptor-kinase-like protein Stb6 controls gene-for-gene resistance to fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Nature genetics. 2018;50(3):368–74. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0051-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saintenac C, Cambon F, Aouini L, Verstappen E, Ghaffary SM, Poucet T, et al. A wheat cysteine-rich receptor-like kinase confers broad-spectrum resistance against Septoria tritici blotch. Nature Communications. 2021;12(1):433. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20685-0 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafeez AN, Chartrain L, Feng C, Cambon F, Clarke M, Griffiths S, et al. Septoria tritici blotch resistance gene Stb15 encodes a lectin receptor-like kinase. bioRxiv. 2023:2023–09. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meile L, Croll D, Brunner PC, Plissonneau C, Hartmann FE, McDonald BA, et al. A fungal avirulence factor encoded in a highly plastic genomic region triggers partial resistance to septoria tritici blotch. New Phytologist. 2018;219(3):1048–61. doi: 10.1111/nph.15180 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan CJ, Zhou B, Benbow HR, Ajaz S, Karki SJ, Hehir JG, et al. Taxonomically restricted wheat genes interact with small secreted fungal proteins and enhance resistance to Septoria tritici blotch disease. Frontiers in plant science. 2020;11:433. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00433 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou B, Benbow HR, Brennan CJ, Arunachalam C, Karki SJ, Mullins E, et al. Wheat encodes small, secreted proteins that contribute to resistance to Septoria tritici blotch. Frontiers in Genetics. 2020;11:469. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00469 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kema GH, van Silfhout CH. Genetic variation for virulence and resistance in the wheat-Mycosphaerella graminicola pathosystem III. Comparative seedling and adult plant experiments. Phytopathology. 1997;87(3):266–72. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.3.266 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods. 2001; 25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiley AM, Foster GD, Bailey AM. Exploring the genetic regulation of asexual sporulation in Zymoseptoria tritici. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018;9:1859. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01859 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin SB, Ben M’Barek S, Dhillon B, Wittenberg AH, Crane CF, Hane JK, et al. Finished genome of the fungal wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola reveals dispensome structure, chromosome plasticity, and stealth pathogenesis. PLoS genetics. 2011; 7(6):e1002070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002070 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll AM, Sweigard JA, Valent B. Improved vectors for selecting resistance to hygromycin. Fungal Genetics Reports. 1994;41(1):22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derbyshire MC, Michaelson L, Parker J, Kelly S, Thacker U, Powers SJ, et al. Analysis of cytochrome b5 reductase-mediated metabolism in the phytopathogenic fungus Zymoseptoria tritici reveals novel functionalities implicated in virulence. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2015;82:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.05.008 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derbyshire MC, Gohari AM, Mehrabi R, Kilaru S, Steinberg G, Ali S, et al. Phosphopantetheinyl transferase (Ppt)-mediated biosynthesis of lysine, but not siderophores or DHN melanin, is required for virulence of Zymoseptoria tritici on wheat. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):17069. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35223-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilo P, Tiley AM, Lawless C, Karki SJ, Burke J, Feechan A. A rapid fungal DNA extraction method suitable for PCR screening fungal mutants, infected plant tissue and spore trap samples. Physiological and molecular plant pathology. 2022;117:101758. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keon J, Antoniw J, Carzaniga R, Deller S, Ward JL, Baker JM, et al. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycosphaerella graminicola to programmed cell death (PCD) of its susceptible wheat host. Molecular plant-microbe interactions. 2007;20(2):178–93. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-2-0178 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skinner W. Non-pathogenic mutants of Mycosphaerella graminicola (Doctoral dissertation, University of Bristol).http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.391093.

- 32.Schindelin J, Rueden CT, Hiner MC, Eliceiri KW. The ImageJ ecosystem: An open platform for biomedical image analysis. Molecular reproduction and development. 2015;82(7–8):518–29. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22489 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart EL, Hagerty CH, Mikaberidze A, Mundt CC, Zhong Z, McDonald BA. An improved method for measuring quantitative resistance to the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici using high-throughput automated image analysis. Phytopathology. 2016;106(7):782–8. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-01-16-0018-R . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karisto P, Hund A, Yu K, Anderegg J, Walter A, Mascher F, et al. Ranking quantitative resistance to Septoria tritici blotch in elite wheat cultivars using automated image analysis. Phytopathology. 2018;108(5):568–81. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-17-0163-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almagro Armenteros JJ, Tsirigos KD, Sønderby CK, Petersen TN, Winther O, Brunak S, et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nature biotechnology. 2019;37(4):420–3. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, et al. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic acids research. 2015; 43(D1):D222–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyal Z. The Septoria diseases of wheat: concepts and methods of disease management. Cimmyt; 1987.

- 38.Tiley AM, White HJ, Foster GD, Bailey AM. The ZtvelB gene is required for vegetative growth and sporulation in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019;10:2210. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02210 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah J, Zeier J. Long-distance communication and signal amplification in systemic acquired resistance. Frontiers in plant science. 2013; 4:30. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00030 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ajigboye OO, Jayaweera DP, Angelopoulou D, Ruban AV, Murchie EH, Pastor V, et al. The role of photoprotection in defence of two wheat genotypes against Zymoseptoria tritici. Plant Pathology. 2021; 70(6):1421–35. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li R, Zhang X, Zhao B, Song P, Zhang X, Wang B, et al. Wheat Class III Peroxidase TaPOD70 is a potential susceptibility factor negatively regulating wheat resistance to Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici. Phytopathology®. 2023;113(5):873–83. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-01-23-0001-FI . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kettles GJ, Bayon C, Canning G, Rudd JJ, Kanyuka K. Apoplastic recognition of multiple candidate effectors from the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici in the nonhost plant Nicotiana benthamiana. New Phytologist. 2017; 213(1):338–50. doi: 10.1111/nph.14215 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamoun S. A catalogue of the effector secretome of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006. Sep 8; 44(1):41–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143436 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hogenhout SA, Van der Hoorn RA, Terauchi R, Kamoun S. Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Molecular plant-microbe interactions. 2009; 22(2):115–22. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0115 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rafiqi M, Jelonek L, Akum NF, Zhang F, Kogel KH. Effector candidates in the secretome of Piriformospora indica, a ubiquitous plant-associated fungus. Frontiers in plant science. 2013; 4:228. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00228 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palma-Guerrero J, Ma X, Torriani SF, Zala M, Francisco CS, Hartmann FE, et al. Comparative transcriptome analyses in Zymoseptoria tritici reveal significant differences in gene expression among strains during plant infection. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2017; 30(3):231–44. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-16-0146-R . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sánchez-Vallet A, McDonald MC, Solomon PS, McDonald BA. Is Zymoseptoria tritici a hemibiotroph?. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2015; 79:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C, Fang H, Shi X, He F, Wang R, Fan J, et al. A fungal effector and a rice NLR protein have antagonistic effects on a Bowman–Birk trypsin inhibitor. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2020; 18(11):2354–63. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13400 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin CH, Pan YC, Ye NH, Shih YT, Liu FW, Chen CY. LsGRP1, a class II glycine‐rich protein of Lilium, confers plant resistance via mediating innate immune activation and inducing fungal programmed cell death. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2020;21(9):1149–66. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12968 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kramerova IA, Kawaguchi N, Fessler LI, Nelson RE, Chen Y, Kramerov AA, et al. Papilin in development; a pericellular protein with a homology to the ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Development. 2000; 127(24):5475–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5475 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahman A, Doohan F, Mullins E. Quantification of in planta Zymoseptoria tritici progression through different infection phases and related association with components of aggressiveness. Phytopathology. 2020;110(6):1208–15. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-19-0339-R . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mustafa Z, Ölmez F, Akkaya M. Inactivation of a candidate effector gene of Zymoseptoria tritici affects its sporulation. Molecular Biology Reports. 2022; 49(12):11563–71. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07879-z . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perelló A, Cordo CA, Alippi HE. Características morfológícas y patogénicas de aislamientos de Septoria tritici Rob ex Desm. Agronomie. 1990;10(8):641–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adhikari TB, Balaji B, Breeden J, Goodwin SB. Resistance of wheat to Mycosphaerella graminicola involves early and late peaks of gene expression. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 2007; 71(1–3):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ray S, Anderson JM, Urmeev FI, Goodwin SB. Rapid induction of a protein disulfide isomerase and defense-related genes in wheat in response to the hemibiotrophic fungal pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Plant molecular biology. 2003; 53:741–54. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000019120.74610.52 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orton ES, Rudd JJ, Brown JK. Early molecular signatures of responses of wheat to Zymoseptoria tritici in compatible and incompatible interactions. Plant pathology. 2017; 66(3):450–9. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12633 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ors ME, Randoux B, Selim S, Siah A, Couleaud G, Maumené C, et al. Cultivar‐dependent partial resistance and associated defence mechanisms in wheat against Zymoseptoria tritici. Plant Pathology. 2018; 67(3):561–72. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Child HT, Deeks MJ, Rudd JJ, Bates S. Comparison of the impact of two key fungal signalling pathways on Zymoseptoria tritici infection reveals divergent contribution to invasive growth through distinct regulation of infection‐associated genes. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2023; 24(10):1220–37. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13365 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shetty NP, Kristensen BK, Newman MA, Møller K, Gregersen PL, Jørgensen HL. Association of hydrogen peroxide with restriction of Septoria tritici in resistant wheat. Physiological and molecular plant pathology. 2003; 62(6):333–46. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shetty NP, Jensen JD, Knudsen A, Finnie C, Geshi N, Blennow A, et al. Effects of β-1, 3-glucan from Septoria tritici on structural defence responses in wheat. Journal of experimental botany. 2009; 60(15):4287–300. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp269 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reilly A, Karki SJ, Twamley A, Tiley AM, Kildea S, Feechan A. Isolate-Specific Responses of the Nonhost Grass Brachypodium distachyon to the Fungal Pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici Compared with Wheat. Phytopathology®. 2021; 111(2):356–68. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-20-0041-R . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hückelhoven R, Kogel KH. Reactive oxygen intermediates in plant-microbe interactions: who is who in powdery mildew resistance?. Planta. 2003. Apr;216:891–902. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-0973-z . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nimchuk Z, Eulgem T, Holt BF Iii, Dangl JL. Recognition and response in the plant immune system. Annual review of genetics. 2003. Dec;37(1):579–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142628 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A, Diagram showing the location of the two primer pairs used to confirm successful transformation of Z. tritici. The replacement of Zt11 by the hygromycin-trpC resistance cassette through homologous recombination is depicted by dotted blue lines on the flanking regions. B, Successful disruption of the Zt11 gene in the mutants indicated by presence of the KO amplicon (2340 base pairs) and absence of the Zt11 wild-type WT amplicon (2124 base pairs). 1kb (kilobase) ladder (Bioline).

(TIF)

Each row represents sequences (left flank, hygromycin and right flank) confirmed by amplicon sequencing in the mutant strains.

(TIF)

ΔZt11 mutant strain, WT (IPO323) and ectopic strain pycnidia on wheat cv. Longbow leaves at 21 dpi. Arrows indicate the cirrhus containing pycnidiospores, scale bars representative of 50μm.

(TIF)

Approximately 107 spores/mL of spores was spotted on to three different solid growth media; PDA, YPDA and YEG (supplemented with H2O2 at concentrations 0, 2, 4 and 6mM) and incubated for 7 days at 20°C. Scale bar = 5mm. Images are representative of three independent experiments, with a total of 2 plates per experiment per media type (n = 4).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.