Dear Editor,

Primary central nervous system vasculitis (PCNSV) is a rare inflammatory disorder affecting the blood vessels of the brain and spinal cord. The involvement of spinal cord is much less frequent when compared to the involvement of the brain. Its prevalence ranges between 5% and 40% in different cohorts.[1,2,3,4] Spinal cord involvement can be the first manifestation of PCNSV, although occurrence after a prior cerebral involvement is commoner.[1] We describe a case of chronic progressive paraparesis due to isolated spinal cord involvement in PCNSV, which mimicked a non-compressive dorsal cord myelopathy and was diagnosed by a spinal cord biopsy.

A 23-year-old gentleman presented with progressively increasing paraparesis over the past 2 years. He initially had sudden falls during running due to a feeling of “giving way” of the knees, and thereafter developed difficulty in climbing stairs 2–3 months later. One year after the onset of the disease, he complained of slippage of footwear (with awareness) from the right foot, followed by the left foot a few weeks later. He also developed a band-like sensation over his umbilicus with decreased sensations below it for the past 6 months, along with urinary urgency with occasional incontinence. He was bedridden for the past 4 months, along with complaints of intermittent, brief, painful spasmodic contractions of both legs. There was no associated fecal incontinence, loss of weight or appetite, vision loss, upper limb or brainstem symptoms, fever, constitutional symptoms, rash, orogenital ulcerations, or photosensitivity. He was an active smoker for the past 4 years (8–10 cigarettes/day), and he denied any similar complaints in the family.

Examination revealed spastic paraparesis with power at the hip and knee of 2 / 5 bilaterally and 1 / 5 at the ankle on the Medical Research Council scale. He had lower limb hyperreflexia with bilateral extensor plantar reflex. Sensory examination revealed pan-sensory loss below the umbilicus. The remaining neurologic examination was normal.

A presumptive diagnosis of non-compressive dorsal myelopathy was made. Investigations revealed normal hemogram, liver and renal functions, glycosylated hemoglobin, thyroid functions, and viral markers for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C. Serum venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), antinuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigen, p- and c-anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, rheumatoid factor, and complement levels were normal. Serum aquaporin 4 and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein IgG antibodies were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed 30 cells (all lymphocytes) and mildly increased protein (90 mg/dl) with normal sugar. CSF testing for malignant cytology, stains, cultures, and VDRL were negative.

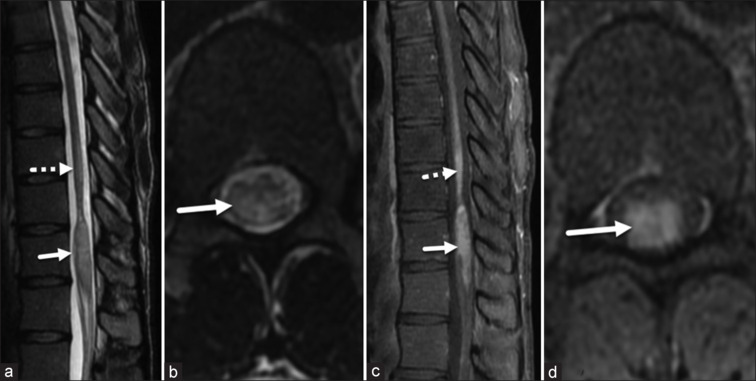

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine done at the onset showed long segment central cord hyperintensity with patchy enhancement in the lower dorsal cord extending from D8 to D11 vertebral levels with sparing of the conus [Supplementary Figure 1 (588.3KB, tif) ]. Another spine MRI was repeated 2 years after the onset of the disease when he presented to us, which showed regression of cord signal change but persistent enhancement, with a new lesion involving the conus [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sagittal (a) and axial (b) T2-WIs demonstrate a partial reduction in the previous expansion and T2 hyperintensity of the spinal cord (dotted arrow in a), alongside persistent enhancement (dotted arrow in c) at the D10–D11 level. In addition, the conus at the D12–L1 level shows expansion, T2 hyperintensity (arrows in a, b), and enhancement (arrows in c, d)

T2-WIs: T2-weighted images

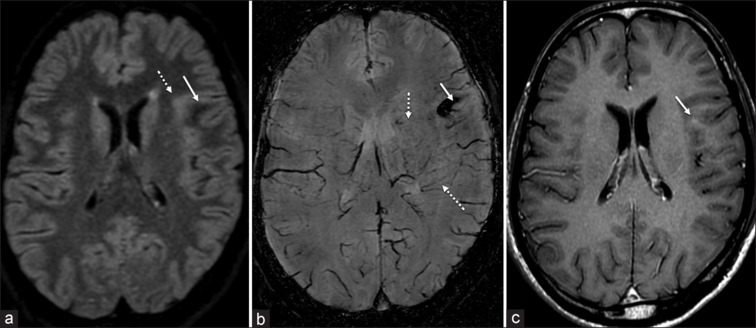

He underwent a targeted diagnostic biopsy of the spinal cord lesion, which revealed granulomatous vasculitis [Supplementary Figure 2 (261.6KB, tif) ]. MRI of the brain conducted at this stage revealed the presence of microhemorrhages with adjacent multiple dot-like and linear susceptibility signals, white matter hyperintensity on Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, and dot-like enhancement in the left frontal region, suggesting asymptomatic brain involvement [Figure 2]. He was treated with intravenous pulse methylprednisolone (1 g) for 5 days, followed by monthly intravenous infusions of cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2) for six doses. Oral steroids were gradually tapered and stopped over 3 months. He showed some improvement and could walk with support at 1-year follow-up.

Figure 2.

Axial FLAIR image (a) demonstrates a focal area of increased signal intensity (dotted arrow) surrounding an area of decreased signal intensity (arrow) in the left frontal lobe. The region of decreased FLAIR signal appears dark on SWI, indicating the presence of microhemorrhages with multiple adjacent dot-like and linear susceptibility signals. Post-contrast T1-weighted image (c) reveals punctate enhancement (arrow)

Spinal cord involvement in PCNSV is rare and was reported to be 5% by Salvarani et al.[1] Among the reported cases, only one patient was found to have spinal cord involvement without cerebral symptoms. An Indian cohort found spinal cord involvement in approximately 40% of patients.[4] However, not all these lesions were symptomatic and they were found because of an imaging protocol of spine screening in patients with cerebral symptoms of PCNSV. The usual age of occurrence of PCNSV is in the third or fourth decade,[5] as was in our patient. Our patient had an inflammatory CSF picture. Similar results have been reported in literature of nearly all PCNSV patients with spinal cord involvement.[1] Most previous histopathologically proven PCNSV cases with spinal cord manifestations underwent a brain biopsy due to concomitant brain lesions and were found to have either granulomatous or necrotizing type of PCNSV.[1] Ours is perhaps one of the very few cases of PCNSV to be diagnosed by a spinal cord biopsy. Our patient was also found to have a granulomatous vasculitis, probably indicative of predominance with regards to spinal cord involvement. He did not show remarkable improvement with treatment. Agarwal et al.[4] described the presence of spinal cord involvement as a poor prognostic factor in functional outcomes.

MRI of the brain was done post-histopathologic diagnosis, which revealed microbleeds on susceptibility-weighted imaging suggestive of PCNSV. We emphasize screening the brain in patients with suspected inflammatory involvement of the cord. This may reveal important diagnostic clues, for example, the presence of microbleeds on Susceptibility Weighted Imaging (SWI) of the brain should raise the suspicion of PCNSV.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Figures

Sagittal (a) and axial (c) T2-WIs show central cord hyperintensity with mild cord expansion in the lower dorsal cord (D8–D11). Sagittal (b) and axial (d) post-gad T1-WIs show patchy central cord enhancement

T1-Wis: T1-weighted images, T2-WIs: T2-weighted images

Spinal cord biopsy revealing granulomatous vasculitis

References

- 1.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Huston J, 3rd, Meschia JF, et al. Primary CNS vasculitis with spinal cord involvement. Neurology. 2008;70:2394–400. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000314687.69681.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Hunder GG. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis. Lancet. 2012;380:767–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.deBoysson H, Zuber M, Naggara O, Neau JP, Gray F, Bousser MG, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: description of the first fifty-two adults enrolled in the French cohort of patients with primary vasculitis of the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024;66:1315–26. doi: 10.1002/art.38340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal A, Sharma J, Srivastava MVP, Sharma MC, Bhatia R, Dash D, et al. Primary CNS vasculitis (PCNSV): A cohort study. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13494. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17869-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajj-Ali RA, Singhal AB, Benseler S, Molloy E, Calabrese LH. Primary angiitis of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:561–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sagittal (a) and axial (c) T2-WIs show central cord hyperintensity with mild cord expansion in the lower dorsal cord (D8–D11). Sagittal (b) and axial (d) post-gad T1-WIs show patchy central cord enhancement

T1-Wis: T1-weighted images, T2-WIs: T2-weighted images

Spinal cord biopsy revealing granulomatous vasculitis