Dear Editor,

Myasthenia gravis (MG) and Morvan’s syndrome (MoS) represent distinct neuromuscular disorders. The former manifests as an impairment of neuromuscular junction transmission, resulting in fatigable weakness, while the latter induces peripheral and central nervous system hyperexcitability, leading to neuromyotonia, autonomic instability, and encephalitis. The common thread uniting these conditions is the underlying autoimmune pathogenesis, coupled with close associations with neoplastic thymic pathologies. In both conditions, autoimmune-mediated pathogenesis involves autoantibodies that target postsynaptic receptors in MG and autoantibodies against the contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CASPR2) cell membrane protein in MoS.[1] Despite certain shared features, the coexistence of MG and MoS remains exceedingly rare, presenting diagnostic and management challenges. This case report aims to shed light on the clinical features, serology, thymic pathology, and the management outcomes associated with this unusual combination of autoimmune-mediated paraneoplastic disorders.

A 61-year-old male had onset of symptoms 5 years ago, characterized by fatigable weakness of limbs. Over the subsequent 2 years, he observed fatigable drooping of eyelids and fluctuating binocular diplopia. Three years into the illness, he was admitted to another facility with progressive dysphagia, dysarthria, fatigable chewing difficulty, and worsening limb weakness. A diagnosis of generalized MG was established, supported by a decremental response in repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) and positive acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibody titers. Treatment with oral steroids and pyridostigmine provided complete relief, and he remained well until 1 year ago when he was readmitted due to an impending myasthenia crisis following treatment discontinuation. Concurrently, he developed burning paresthesia in both feet, along with muscle twitching. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (2 g/kg over 5 days) was administered, and azathioprine was initiated, which resulted in a 60% improvement in his myasthenic symptoms.

Upon presentation to our center, the patient suffered severe burning paresthesia affecting all extremities along with muscle twitching, initially in the calves and progressively spreading throughout the body. In addition, he reported excessive sweating, urinary urgency and incontinence, prolonged sleep latency with fragmented sleep, worsening anxiety with mood fluctuations, and recent memory disturbances. Notably, there was no history of exposure to heavy metals or indigenous medications.

On examination, he had impaired attention, verbal, and visual memory. He had bilateral fatigable asymmetric ptosis with positive ice pack test, restriction of elevation and abduction of eyes not correctable with vestibulo-ocular reflex, bilateral lower motor neuron facial weakness, flaccid dysarthria, hypophonic speech, and mild neck and proximal limb weakness. There was florid myokymia prominently over both calves. The deep tendon reflexes were sluggish, and sensory examination revealed severe hyperalgesia over legs and normal vibration and proprioception.

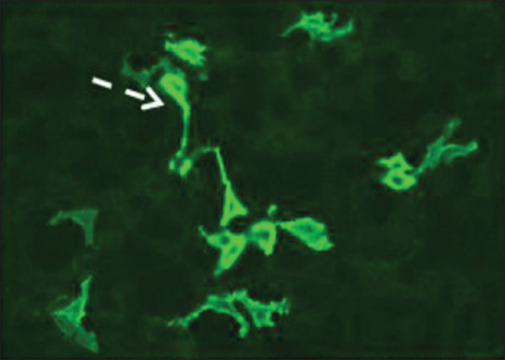

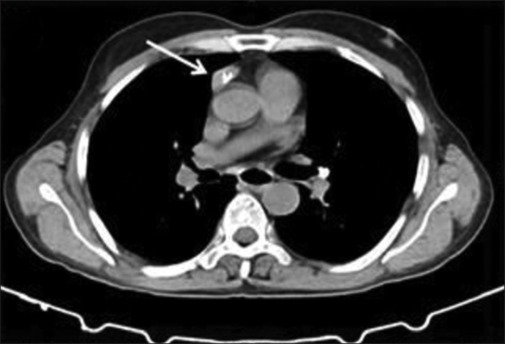

Electro neuro-myography showed diffuse myokymia [Supplementary Figure 1 (245.2KB, tif) ], and RNS showed decremental response [Supplementary Figure 2 (458KB, tif) ]. AChR antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) was positive (>8 u/L). Serum autoimmune profile showed anti-CASPR2 antibody strongly positive [Figure 1]. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest revealed thymoma [Figure 2], and whole-body positron emission tomography–magnetic resonance imaging showed no increased uptake.

Figure 1.

Indirect immunofluorescence for CASPR2 showing strong cytoplasmic and membrane labeling of cell lines expressing CASPR2 (interrupted arrow), CASPR2: contactin-associated protein-like 2

Figure 2.

CECT showing thymoma (white arrow), CECT: contrast-enhanced computed tomography

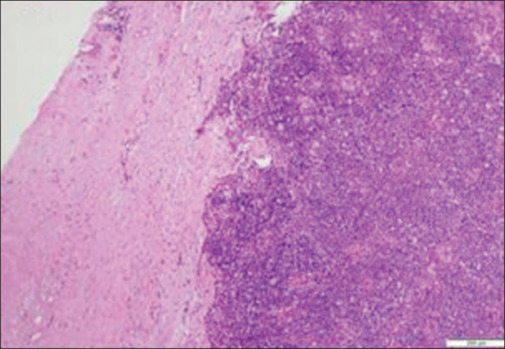

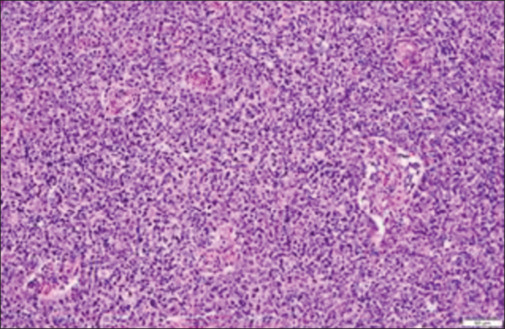

He received five cycles of high-volume plasmapheresis and was gradually titrated on steroids. Despite being on carbamazepine, pregabalin, lamotrigine, and clonazepam, he continued to have troubling paresthesia and myokymia. During the 1-month hospital stay, his myasthenia was stabilized and he underwent total thymectomy. The histopathologic examination revealed thymoma type 2B [Figures 3 and 4]. At 4 months follow-up after surgery, he had near-complete resolution of all his symptoms due to both MG and MoS and was continued on azathioprine with plan for steroid taper.

Figure 3.

Low magnification showing altered architecture of the thymus with intact capsule

Figure 4.

Higher magnification showing an admixture of epithelial cells and lymphocytes component in thymoma B2

The current case illustrates the coexistence of seropositive MG and MoS in a patient with thymoma B2, who had an excellent outcome with timely immunomodulation and thymectomy. Thymoma is observed in 10%–15% of patients with generalized MG, while it can be encountered in up to 40% of patients with MoS, hence MG and MoS are considered as paraneoplastic syndromes.[2,3] MG–MoS remains a very rare combination of two autoimmune/paraneoplastic disorders that manifests as an unusual multiaxial and potentially curable symptom complex.

Gastaldi et al.,[4] in their examination of 268 patients with thymomatous MG, identified two cases with MoS and an additional three patients with neuromyotonia that lacked central nervous system involvement. In contrast, in the largest series of 29 MoS cases, nine individuals were diagnosed with AChR-positive MG, and all of them had thymoma.[3] The intricate pathogenesis underlying this shared autoimmunity could involve a decreased immune tolerance due to the absence of autoimmune regulator and major histocompatibility complex class II expression, diminished T regulatory cells, and the escape of immature autoreactive T cells.[5] Furthermore, a genetic predisposition is suggested, supported by at least one case report associating pathogenic variants in the MEFV gene with MG–MoS.[6]

A review of MG–MoS cases reveals several consistent clinical features [Supplementary Table 1]. Notably, patients with MG–MoS tend to have a later age of onset compared to those with MG.[5] There is a pronounced male predominance, and MG typically manifests in a generalized form, either preceding or occurring simultaneous with the onset of MoS. Nearly all patients exhibit seropositivity for both AChR and CASPR/LGI antibodies, and the presence of thymoma or its recurrence is almost universally associated. Type B2 thymoma is the pathology most frequent in MG–MoS.

Supplementary Table 1.

Reported cases of Myasthenia Gravis (MG) with Morvan’s syndrome (MoS)

| Author | Year of Publication | Number of Patients | Age/Gender | Initial Presentation | Duration From MG to MoS | Antibody Status | Thymus Status | Treatment | Outcome | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Briani et al.[8] | 2010 | 1 | 40/M | Generalised MG followed by MoS | 1 year | AchR and VGKC positive | Thymoma (B3) | IVIG with steroids | Death | MoS with recurrence of thymoma |

| Lee et al.[9] | 1998 | 1 | 46/M | Generalised MG followed by MoS | 1 year | AchR and VGKC positive | Non-invasive cortical thymoma (B2) | PE with steroids and azathioprine | Improved | Associated with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis |

| Nagappa et al.[7] | 2017 | 1 | 54/M | MG followed by MoS | NS | NS | Thymectomy not done | NS | Death | NS |

| Weiss et al. | 2012 | 1 | 22/M | Simultaneous | - | Both Positive | - | Steroids, IVIG and Rituximab | Improved | Associated with Kawasaki Disease |

| Anna Sadnika et al. | 2010 | 1 | 76/M | Generalised MG followed by MoS | 6 years | Both antibodies and anti-striational antibodies positive | Underwent thymectomy before MoS onset (Biopsy NA) | PE, IVIG, steroids and Rituximab | NS | Co-existent CIDP |

| Koge et al | 2016 | 1 | 40/F | MG followed by MoS | 1 year | Both positive | - | IVMP, PE and IVIG | Frequent relapses | complicated with MEFV gene mutations |

| Gwenolé Abgrall et al | 2015 | 1 | 60/M | MG followed by MoS | 8 years | Both positive | Thymoma | IVMP, PE and IVIG and Rituximab | Partially improved | Status dissociatus and disturbed dreaming |

| Huiqin Liu et al | 2022 | 1 | 49/M | MG followed by MoS | 1 year | Both positive with anti LGI-1, GABABR and titin positive | Thymoma | Steroids, IVIG and Rituximab | Improved | Associated nephrotic syndrome and cutaneous amyloidosis |

| Manera et al | 2007 | 1 | 46/F | Simultaneous | - | Both and anti-MuSK positive | Thymic hyperplasia | prednisolone, IVIG, ciclosporin, and rituximab | Improved | - |

| Yasuo et al | 1989 | 1 | 30/M | Simultaneous | - | NA | Thymoma | Steroids | Improved | - |

| Seong-il Oh et al | 2022 | 1 | 67/M | Generalised MG followed by MoS | 2 years | AchR positive and other anitbodies unavailable | Thymoma | Symptomatic treatment | Status quo | - |

| Masrori et al | 2020 | 1 | 63/M | Ocular myasthenia followed by MoS | 13 years | CASPR2 positive | Thymoma | Steroids, PE and azathioprine | Improved | - |

| Evoli et al.[10] | 2002 | 4 NMT; 1 LE out of 207 patients with MG operated for thymoma | NA | MG followed by MoS | NA | VGKC negative | Thymoma | PE | Improved | MoS was transient and improved quickly. |

| Irani et al.[3] | 2012 | 9 | NA | NA | NA | CASPR2 and AChR positive in all | Thymoma in all patients with MoS and MG | PE, IVIG, IVMP | Outcome poor compared to those without thymoma | NS |

| Gastaldi et al.[4] | 2019 | 5 NMT; 2/5 MoS | 42.2* (3F, 2M) | MG | NA | AChR positive, CASPR, LGI, Netrin | Thymoma B2 | Thymectomy, IST | 2 MoS- 1 death, 1 remission | NS |

*Mean age (33- 57 range). AchR: Acetylcholine receptor, CASPR -2: Anti-contactin-associated protein-like 2, CIDP: Chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy, F: Female, IST- Immunosuppressive Therapy, IVMP: Intravenous Methylprednisolone, IVIG: Intravenous Immunoglobulin, LGI-1: Leucine rich glioma inactivated-1, LE: Limbic Encephalitis, M: Male, MoS: Morvan’s syndrome, MuSK: Muscle specific kinase, MG: Myasthenia Gravis, NMT: Neuromyotonia, NA: Not available, PE: Plasma exchange, VGKC: Voltage gated potassium channel, NS: Not specified

The present case aligns with previous reports in terms of male gender, MG as the inaugural symptom, association with B2 thymoma, and positive serology. However, it diverges in exhibiting an excellent outcome following thymectomy, despite the generally poor prognosis observed in patients with combined MoS and thymoma.[3,5,7] The antibodies mediating pathology in MG–MoS involve IgG1 and IgG3, triggering a complement-mediated attack on AChR. In contrast, MoS involves IgG4, which prevents CASPR2–contactin binding through non–complement-mediated mechanisms. Consequently, conventional immunomodulators like IVIG and steroids may prove insufficient, emphasizing the role of rituximab in such scenarios. This case underscores the significance of adequate pretreatment and timely thymectomy in effectively mitigating the autoimmune milieu.

Early recognition of MG–MoS is crucial and requires identification of red flag symptoms such as paresthesia, sleep disturbances, memory issues, and muscle twitches in MG. Caution is advised before dismissing these symptoms, which may be at times misconstrued as anxiety or drug related.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Screen shot of EMG from right vastus lateralis (sweep speed 100ms/division, sensitivity 200µV/division showing irregular bursts of myokymic discharges

Repetitive nerve stimulation showing decremental responses from left trapezius at baseline and successively 1,2,3 and 4 minutes after 60 seconds of exercise

References

- 1.Phillips WD, Vincent A. Pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis: Update on disease types, models, and mechanisms. F1000Res. 2016;5 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8206.1. F1000 Faculty Rev-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menon D, Katzberg H, Barnett C, Pal P, Bezjak A, Keshavjee S, et al. Thymoma pathology and myasthenia gravis outcomes. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63:868–73. doi: 10.1002/mus.27220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irani SR, Pettingill P, Kleopa KA, Schiza N, Waters P, Mazia C, et al. Morvan syndrome: Clinical and serological observations in 29 cases. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:241–55. doi: 10.1002/ana.23577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gastaldi M, De Rosa A, Maestri M, Zardini E, Scaranzin S, Guida M, et al. Acquired neuromyotonia in thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis: A clinical and serological study. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:992–9. doi: 10.1111/ene.13922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura K, Okada Y, Fujii C, Komatsu K, Takahashi R, Matsumoto S, et al. Clinical characteristics of autoimmune disorders in the central nervous system associated with myasthenia gravis. J Neurol. 2019;266:2743–51. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koge J, Hayashi S, Murai H, Yokoyama J, Mizuno Y, Uehara T, et al. Morvan’s syndrome and myasthenia gravis related to familial mediterranean fever gene mutations. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:68. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0533-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagappa M, Mahadevan A, Sinha S, Bindu PS, Mathuranath PS, Bineesh C, et al. Fatal Morvan syndrome associated with myasthenia gravis. Neurologist. 2017;22:29–33. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briani C, Cagnin A, Blandamura S, Altavilla G. Multiple paraneoplastic diseases occurring in the same patient after thymomectomy. J Neurooncol. 2010;99:287–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0130-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EK, Maselli RA, Ellis WG, Agius MA. Morvan’s fibrillary chorea: A paraneoplastic manifestation of thymoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:857–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.6.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evoli A, Minisci C, Di Schino C, Marsili F, Punzi C, Batocchi AP, et al. Thymoma in patients with MG: characteristics and long-term outcome. Neurology. 2002;59:1844–50. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000032502.89361.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Screen shot of EMG from right vastus lateralis (sweep speed 100ms/division, sensitivity 200µV/division showing irregular bursts of myokymic discharges

Repetitive nerve stimulation showing decremental responses from left trapezius at baseline and successively 1,2,3 and 4 minutes after 60 seconds of exercise