Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Continuous advancements and breakthroughs in flexible GI endoscopy have led to alternatives to colonic anastomosis.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of end-to-end colonic anastomosis using a single flexible endoscope with the novel through-the-scope “bow-tie” device and conventional metal clips in a porcine model.

DESIGN:

Animal study.

SETTINGS:

Animal laboratory at China Medical University.

PATIENTS:

Eight healthy pigs were included.

INTERVENTIONS:

Eight animals underwent total colonic severance and anastomoses with through-the-scope “bow-tie” devices and metal clips.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

The primary outcomes were the success rate of the anastomosis and survival rate during 3-month follow-up. Furthermore, the secondary outcomes were anastomotic site healing, reintervention rate, and rate of anastomotic complications such as bleeding, leakage, stenosis, and obstruction. Six pigs were euthanized, and necropsies were performed 3 months postoperatively, whereas 2 pigs were fed for long-term observation. The anastomotic stoma was histologically analyzed using hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome staining.

RESULTS:

End-to-end colonic anastomoses were successfully performed using through-the-scope “bow-tie” devices and metal clips, and satisfactory healing was achieved in all pigs. The success rate of anastomosis was 100% (8/8). All animals survived postoperatively without anastomotic complications, including bleeding, leakage, or obstruction; however, 2 cases of stenosis occurred (25%) and 1 case (12.5%) required reintervention.

LIMITATIONS:

Large-scale studies should be conducted to verify the feasibility and safety of the through-the-scope “bow-tie” device in other parts of the intestine.

CONCLUSIONS:

Flexible endoscopy with the through-the-scope “bow-tie” device is feasible and safe for intraluminal colonic anastomosis. This study may expand the indications for full-thickness endoscopic resection in the future. See Video Abstract.

LA FALTA DE ACCESO REGULAR A UN MÉDICO DE ATENCIÓN PRIMARIA SE ASOCIA CON UN AUMENTO DE VISITAS AL DEPARTAMENTO DE EMERGENCIA RELACIONADAS CON LAS NECESIDADES DE SUPERVIVENCIA ENTRE LOS SOBREVIVIENTES DE CÁNCER DE RECTO

ANTECEDENTES:

Con los avances en el tratamiento del cáncer de recto y el mejor pronóstico, hay un número creciente de sobrevivientes de cáncer de recto con necesidades únicas.

OBJETIVOS:

Presumimos que una proporción significativa de nuestros sobrevivientes de cáncer de recto carecen de acceso regular a un médico de atención primaria. El objetivo de nuestro estudio fue examinar la asociación entre el acceso a un médico de atención primaria y las visitas al departamento de emergencias relacionadas con la supervivencia.

DISEÑO:

Estudio de cohorte retrospectivo de supervivientes de cáncer de recto que finalizaron todo el tratamiento.

PACIENTES:

Pacientes con cáncer de recto que se sometieron a proctectomía y completaron el tratamiento entre 2005 y 2021.

ESCENARIO:

Centro único de atención terciaria en Quebec, Canadá.

MEDIDA DE RESULTADO PRINCIPAL:

Visitas al departamento de emergencias relacionadas con la supervivencia.

RESULTADOS:

En total, se incluyeron 432 sobrevivientes de cáncer de recto. La mediana de edad fue 72 (rango intercuartil 63-82) años, 190 (44,0%) eran mujeres y la mediana del índice de comorbilidad de Charlson fue 5 (rango intercuartil, 4-6). Había 153 (35,4%) personas no registradas con un médico de atención primaria. Sesenta personas visitaron el departamento de emergencias debido a preocupaciones relacionadas con la supervivencia. Utilizando el análisis de riesgos proporcionales de Cox, la falta de registro con un médico de atención primaria se asoció con una mayor probabilidad de tener visitas al departamento de emergencias relacionadas con la supervivencia.

LIMITACIONES:

Este estudio estuvo limitado por el diseño observacional.

CONCLUSIÓN:

La falta de acceso regular a un médico de atención primaria puede contribuir al aumento de las visitas al departamento de emergencia entre los sobrevivientes de cáncer de recto. Se necesitan esfuerzos para mejorar el acceso al médico de atención primaria y coordinar la atención interdisciplinaria para mejorar la atención a los sobrevivientes. (Traducción—Dr Osvaldo Gauto)

Keywords: Colonic anastomosis, Endoscopic defect closure, Endoscopic full-thickness resection, End-to-end anastomosis

Video Abstract

Video Abstract.

Endoscopic resection (ER) procedures in the GI tract have experienced rapid progress in recent decades, making it possible and attractive to obviate surgical resection. Intraluminal ER procedures can establish the shortest access to the lesion, especially in areas where it is difficult for surgery and laparoscopy, such as the surgical site is far from the anus,1 the pelvic cavity is narrow,2 and the mesenteries are not long enough to be extracted outside the abdominal cavity.3 In 2001, Suzuki and Ikeda4 introduced endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) to treat GI malignancies. Gradually, it has been used in the resection of complex colorectal lesions, such as difficult adenomas, early carcinomas, and subepithelial tumors; in difficult anatomical locations; and even for diagnostic purposes.5,6 Because of the uncertainty of the preoperative diagnosis and staging, a full-thickness excision with adequate margins of clearance should be performed. However, colorectal EFTR is challenging in closing the wall defect after resection. Through-the-scope clip (TTSC) may only be used to treat small defects (<10 mm) because of their limited wingspan.7 Larger perforations (10–20 mm) may be treated with over-the-scope clips.8 Defects >30 mm, such as colonic avulsion and linear tear, are rather difficult to close endoscopically.9 The appearance of special suturing instruments solved the problem to some extent. However, bulkier instruments such as Endo Stitch devices and OverStitch systems may require more skills and also make some angles difficult to operate.10,11 This is due to the confined space of the operation area and the high levels of motion dexterity needed for stitching.

We have developed a relatively simple technology that enables gastroenterologists to achieve severed defect closure. A novel through-the-scope “bow-tie” (TTS-BT) device (Fig. 1A) grasps 2 opposite detection edges with 2 clips, and a string is attached to one of the jaws of each clip. Subsequently, a locking knotter device is used to knot the strings like a bow-tie, and the extra strings were cut off with complete locking (Fig. 1B–E). This novel study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of end-to-end colonic anastomosis using a flexible endoscope and accessories (TTS-BT device and TTSC, respectively) in a porcine model.

FIGURE 1.

Physical diagram of the TTS-BT device and schematic diagram illustrating the working principle. A, Image of the TTS-BT device, which consists of 3 components: 2 closure clips with strings and 1 locking device. B, The first clip with string grasps 1 side of the defect. C, The second clip with string grasps the opposite side of the defect. D, A locking device is applied to thread both strings, causing the edges of the defect to be approximated by gently pulling 2 strings. E, The TTS-BT device was successfully applied after cutting the suture and tying the knot. TTS-BT = through-the-scope bow-tie.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Preoperative Preparation

Eight Bama minipigs (6 months old, weighing 15–20 kg) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Science Department of Shengjing Hospital. The Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University, approved the study (registration No. 2022PS1060K). The study was performed in compliance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines.

All animals were fasted from solid food for 3 days; however, they had full access to a glucose solution for energy. One day before the procedure, the animals were administered 4 mL/kg sodium phosphate (Sodium Phosphates Oral Solution, Sinopharm Yibin Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, China) diluted with the same volume of normal saline into the duodenum using gastroscopy. All animals were stabilized in the left recumbent position, and venous access was established via the auricular vein. Anesthesia was induced with a 5 mg/kg IV propofol bolus and administered as a 5 mg/kg/h propofol continuous intravenous infusion. Tracheal intubation was performed to maintain airway patency. All animals underwent continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring and were administered 2 to 3 L/min oxygen using a low-flow nasal oxygen cannula.

Operation Procedure

Artificial colon severance

An endoscopist with experience in endoscopic submucosal dissection and EFTR used an endoscope (EPK-I; Pentax, Tokyo, Japan; EG-500L; SonoScape Medical Corporation, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a transparent cap for all the operations according to previously reported techniques5,6 (Fig. 2). All animals’ colons were severed circumferentially using an insulated-tipped knife (KD-611L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a triangle knife (KD-640L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A 20-gauge needle was inserted into the right abdomen to relieve the pneumoperitoneum after perforation. Subsequently, the endoscope was inserted to quickly scan the surrounding tissue and confirm the severance (Figs. 3A and B). Hemostasis was achieved using hot coagulation forceps (FD-410LR; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

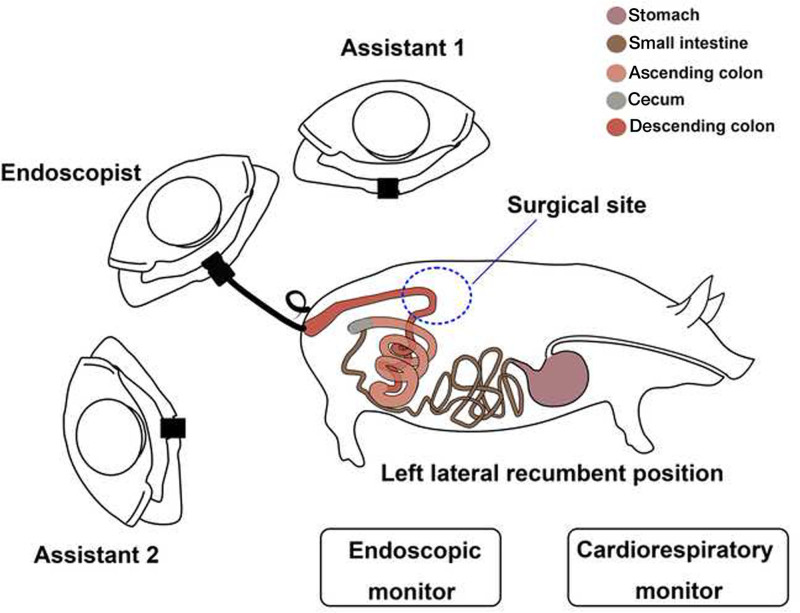

FIGURE 2.

Operating theater setup.

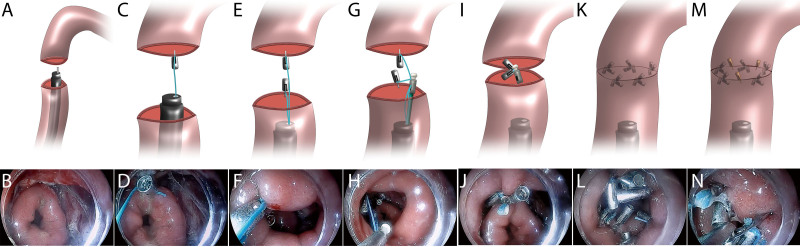

FIGURE 3.

Schema and representative images of end-to-end anastomosis procedure of a porcine colon with TTS-BT devices. A and B, The colon, located 35 cm from the anus, was cut transversally in half. C and D, The severed colon’s oral (proximal) side was clamped using a clip with string. E and F, The severed colon’s anal (distal) side was clamped using another clip with string. G and H, A locking device was applied, and both strings were threaded into it. I and J, Two strings were pulled to bring the clips closer, causing 2 parts of the severed colon to be approximated, and after that, the TTS-BT device was released. K and L, Four sets of TTS-BT devices were consecutively used to achieve primary end-to-end colonic anastomosis. M and N, The remaining small defects were closed with TTSCs. Endoscopy revealed successful end-to-end colonic anastomosis. TTS-BT = through-the-scope bow-tie; TTSC = through-the-scope clip.

All procedures were performed approximately 30 to 35 cm from the anus because the bowel segment is angulated (90° angle) and iatrogenic perforation is easy. Tearing in this colonic section can cause substantial tension, making the operation more challenging. We believe that the TTS-BT device can close iatrogenic perforations if we can achieve the challenge of restoring the continuity and integrity of the severed bowel segment. Online Resources (see Supplemental Fig. 1 at http://links.lww.com/DCR/C390, Supplemental Video 1 at http://links.lww.com/DCR/C426) illustrate procedures for closing large iatrogenic colonic perforations to validate our hypothesis.

End-to-end colonic anastomosis with TTS-BT device

An end-to-end colonic anastomosis was performed using a TTS-BT device (Micro-Tech Co. Ltd, Nanjing, China). First, a clip with an attached string was advanced through the endoscopic working channel. Thereafter, the proximal (oral) part of the severed colon was clamped with a clip (Figs. 3C and D), followed by another clip on the distal (anal) side (Figs. 3E and F). The string ends of the clips were threaded through the locking device and delivered to the colon via the endoscopic working channel. The ends of the severed colon were drawn by gradually pulling the free ends of the strings (Figs. 3G and H). The locking device knots and cuts the strings (Figs. 3I and J). Primary anastomosis of the severed colon was completed using several TTS-BT devices at intervals of <1 cm (Figs. 3K and L). Finally, several conventional metal clips were used to consolidate the anastomosis (Figs. 3M and N). Operating procedures of end-to-end colonic anastomosis are shown in Supplemental Video 2 at http://links.lww.com/DCR/C427 and Supplemental Video 3 at http://links.lww.com/DCR/C428.

Postoperative Management

All animals were fasted for 24 hours postoperatively and fed sweetened milk (2000 mL/day) for 6 days before resuming a regular diet. Cephalosporin antibiotics (Ceftiofur sodium, 0.5 g/d, China Animal Husbandry Co. Ltd) were administered intramuscularly for 3 to 5 days postoperatively. The weight changes, temperature, daily food intake, and bowel movements were recorded daily by an experienced veterinarian. Furthermore, abnormal behaviors indicating pain or disease were monitored. Six pigs were euthanized and necropsies were performed 3 months postoperatively; 2 pigs were observed for further survival experiments for 12 months and were not euthanized.

Evaluation of Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the success rate of the anastomosis and survival rate during 3-month follow-up. The success rate of anastomosis was defined as apposed defect edges and visible continuity. Secondary outcomes were the healing conditions of the anastomotic sites, reintervention rate, and rate of anastomotic complications, such as bleeding, leakage, stenosis, and obstruction.

The success rate of anastomosis, number of devices, and operative time were recorded. Repeat endoscopy was performed during follow-up to evaluate the healing conditions, which were defined as follows: good, featuring neovascularity and white anastomotic edge, and poor, characterized by the lack of neovascularity at the anastomosis, reflecting relative ischemia and predisposing to stricture formation.12 Reintervention was defined as any endoscopic treatment for anastomotic complications, such as hemostasis, leak repair, and dilation. Delayed bleeding was defined as bloody stools. Anastomotic leakage was diagnosed on the basis of the symptoms and signs of clinical peritonitis, including reduced food intake, fever, leukocytosis, abdominal protuberance, muscular tension, and fluid/air bubbles surrounding the anastomosis on CT. Stenosis was defined as anastomotic narrowing through which a 10-mm diameter flexible endoscope could not pass without resistance.

During necropsy, the abdominal cavity and anastomotic stoma were evaluated for peritonitis, ascites, adhesions, and deformities. Six pigs were euthanized in 3 months postoperatively to assess the healing of the anastomosis using hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome staining.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Data are presented as proportion (%, n/N), median (range), and mean ± SD.

RESULTS

The success rate of TTS-BT devices for colonic end-to-end anastomosis was 100% (8/8). The mean number of TTS-BT devices and TTSCs used were 5.0 (4.0–7.0) and 2.0 (0.0–3.0), respectively (Table 1). The learning curve was evident when evaluating the time to perform end-to-end anastomosis with TTS-BT devices, and the first procedural time was 51 minutes, which subsequently decreased to 20 minutes (Table 1; see Supplemental Fig. 2 at http://links.lww.com/DCR/C391). All animals survived postoperatively (100%), and anastomosis healing at 3 months postoperatively was good in all animals (Table 2; 100%). The complication of anastomotic stenosis was reported in 2 of 8 cases (25%) at 3 weeks; no other anastomotic complications, such as bleeding, leakage, or obstruction, occurred. One pig needed reintervention (12.5%) with endoscopic balloon dilation, which relieved the stenosis (see Supplemental Fig. 3 at http://links.lww.com/DCR/C392).

TABLE 1.

Procedure outcomes of end-to-end anastomosis

| Outcomes | Proportion, % (n/N)/median (range) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| The success rate | 100 (8/8) | NA |

| Mean TTS-BT devices | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.4 ± 0.9 |

| Mean TTSCs | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.8 ± 1.4 |

| Procedure time | ||

| Mean time of cutting the colon, min | 6.3 (5.0–23.0) | 9.3 ± 6.1 |

| Mean total procedure time of anastomosis, min | 30.3 (20.0–51.0) | 31.4 ± 10.0 |

| Mean procedure time with TTS-BT, min | 26.8 (20.0–45.0) | 28.6 ± 8.7 |

| Mean procedure time per TTS-BT, min | 4.9 (3.8–11.3) | 5.5 ± 2.4 |

NA = not available; TTS-BT, through-the-scope “bow-tie”; TTSC = through-the-scope clip.

TABLE 2.

Postoperative outcomes of end-to-end anastomosis

| Outcomes | Proportion, % (n/N) |

|---|---|

| Three-month survival rate | 100 (8/8) |

| TTS-BT device spontaneous detachment within 1 mo | 100 (8/8) |

| Endoscopic evaluation of healing condition | |

| Good | 100 (8/8) |

| Poor | 0 (0/8) |

| Complication rate | |

| Delayed bleeding | 0 (0/8) |

| Leakage | 0 (0/8) |

| Stenosis | 25 (2/8) |

| Obstruction | 0 (0/8) |

| Reintervention rate | 12.5 (1/8) |

| Macroscopic evaluation at autopsya (N = 6) | |

| Deformationa | 0 (0/6) |

| Ascitesa | 0 (0/6) |

| Mild and moderate adhesion with surrounding intestinesa |

83.3 (5/6) |

| Severe adhesion with surrounding intestinesa | 16.7 (1/6) |

| Other intraperitoneal adhesiona | 0 (0/6) |

TTS-BT = through-the-scope “bow-tie.”

Six pigs were euthanized for macroscopic evaluation, whereas 2 pigs continued feeding for long-term observation.

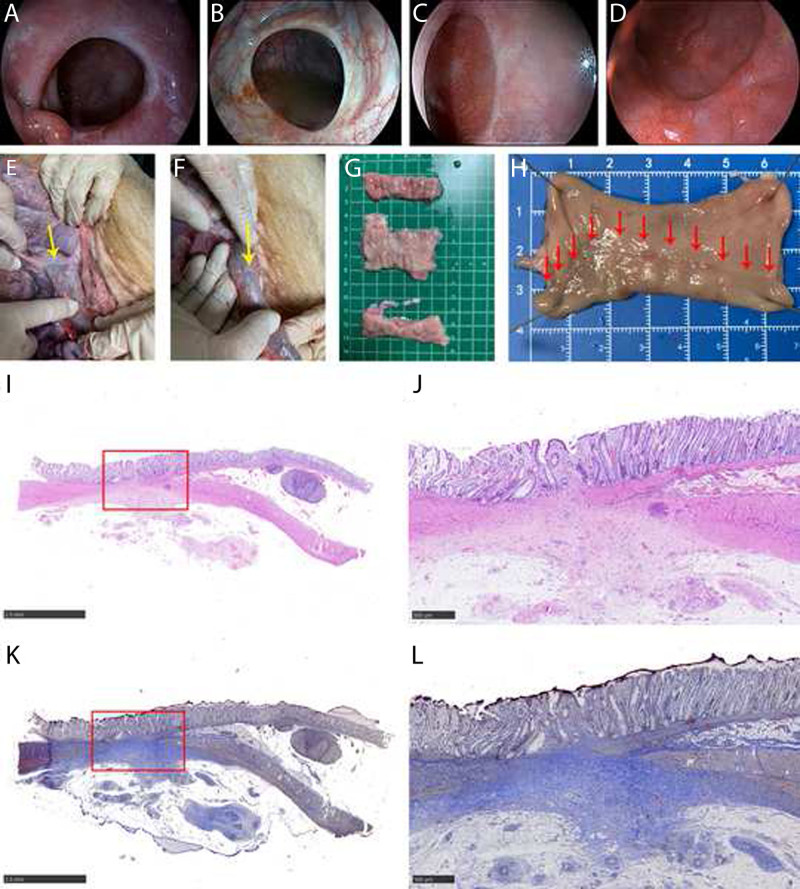

Endoscopy revealed no colonic deformations in any of the animals. Moreover, at necropsy, no peritonitis, ascites, or deformity outside the colon was observed in any of the animals (Fig. 4). The anastomosis mildly adhered to the surrounding intestines in 5 cases (5/6). In contrast, severe adhesion with the surrounding intestines was observed in 1 case (1/6). No intraperitoneal adhesions were observed (0/6). Hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichome staining at 3 months postoperatively revealed mild submucosal and serosal fibrosis, disorganized muscle fiber structure, and partial replacement of the muscle layer by collagen at the anastomotic site (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Representative images of the anastomotic site. A, The anastomosis healed well on POD 30; endoscopy could be easily passed without intervention. B, Endoscopic appearance on POD 90. Small vessels extending radially from the anastomotic line and the white anastomotic edge were typical of what would be seen normally. C and D, Endoscopic appearance on POD 180 and POD 360 made it difficult to identify the anastomosis with only a faint line typically seen. E and F, The serosal aspect of a well-healed colonic anastomotic site (yellow arrow). G, The anastomotic scar and 6 cm above and below the anastomotic line were evaluated. H, Mucosal aspect of a well-healed colonic anastomotic site (red arrow). I and J, HE staining of the anastomosis site: the healing condition was good, as evidenced by a complete colonic mucosa with a mature morphology, fibrous tissue hyperplasia, and collagen deposition. Muscle bundles in the tunica muscularis are disorganized and partially replaced by collagen, fusing with the muscularis mucosa. K and L, Masson trichrome staining of the anastomosis site: hyperplastic fibrous tissue hyperplasia and collagen are green-blue, whereas hyperplastic smooth muscle cells are red. HE = hematoxylin-eosin; POD = postoperative day.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that end-to-end colonic anastomosis using 1 flexible endoscope with TTS-BT devices is feasible. This technique is novel because end-to-end colonic anastomosis has not been addressed in traditional therapeutic endoscopies. All animals underwent successful end-to-end anastomosis, and good healing at anastomotic sites was confirmed during follow-up, demonstrating its technical feasibility. In addition, all pigs survived during the observation period with no serious complications and a low reintervention rate, suggesting the safety of the procedure.

Endoscopic excision of benign and malignant colorectal tumors is an attractive alternative to more invasive surgeries. Indications for EFTR are difficult adenomas, early carcinomas, subepithelial tumors, and EFTR,5,6 in which lesions have a diameter of <3 cm; however, the mean diameter in most reports is <2 cm. Schmidt et al13 reported that the R0 resection rate was lower for colonic lesions >2 cm versus ≤2 cm (58.1% vs 81.2%, p = 0.0038). An adequate extent of resection should be ensured to achieve a higher complete resection rate, which can reduce residual disease and recurrence. EFTR currently has problems with standardization and popularity because it requires closure of strong GI defects, which also limits lesion size (<30 mm) treated.14 Successful endoscopic anastomosis can ensure adequate treatment for defects after ER. This may broaden colonic EFTR indications.

Despite the recent advances in endoscopic techniques, immediate and effective circumferential colonic anastomosis remains challenging. The technical constraints of available endoscopic tools and the narrow colonic lumen make it difficult to manipulate endoscopic platforms with therapeutic suturing function.15 TTSCs are convenient and efficient for managing small perforations but may be inadequate for large defects or complex locations.16 The over-the-scope clip has some limitations concerning its anatomical location, and its closure of defects >4 cm in size is not always successful.17 Moreover, recently invented devices include OverStitches (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX) and endoloop clips for colonic defect closure. However, it may not be possible to introduce special equipment in a narrow lumen. Maneuverability in some segments of the colon is more complicated than that in the stomach and esophagus. Particularly in cases of proximal colon, the long distance and tortuosity of the colon make it difficult for gastroenterologists to manage the defect promptly.

TTS-BT devices have emerged on the basis of TTSC and retain advantages such as simplicity and flexibility. A clip of the TTS-BT device clamps 1 side of the defect at a time. This clamping is easier than the simultaneous application of TTSC clamps on both sides of the defect. Because 1 clip only clamps 1 side of the defect, the TTS-BT device can clamp more tissues to ensure firm defect closure. This novel procedure offers other advantages. This technique can be performed in any endoscopic operating room (Fig. 2) with endoscopy experience without requiring complex machinery or additional infrastructure investment. Through continued innovation, more practice and a summary of the technique tips might help to shorten the procedure time. Furthermore, general anesthesia was administered during this experiment, and we expect intravenous sedation in an endoscopic suite to be an option soon. The anastomotic procedure can be performed using flexible endoscopes and accessories under conscious sedation.

This novel procedure may overcome difficulties for larger-size defects and may extend the application of EFTR to even larger lesions. One potential candidate for its use could be huge subepithelial tumors. In addition, endoscopic anastomosis is preferable in some circumstances, such as when the anastomosis site is far from the anus or at the dorsal side of the intestine,1 the pelvic cavity is narrow,2 or the mesenteries are not long enough to be extracted outside the abdominal cavity.3 We anticipate that the future use of this device will have special benefits at challenging sites in the constricted, fixed, and angulated colonic segments. Furthermore, direct endoscopic anastomosis using TTS-BT devices may be created for rescuers in cases where endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gastroenterostomy fails.18–20

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a pilot study with a relatively small sample size in a porcine model. Second, the anastomosis was performed in the same general area at 30 to 35 cm from the anal verge. Further studies can focus on endoscopic closure with the novel device in GI organs.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings demonstrated that the novel TTS-BT device is safe and effective for colonic anastomosis. In addition, the successful endoscopic colonic anastomosis may increase the indications for EFTR in the future.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.dcrjournal.com).

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070683); Scientific Research Fund of Liaoning Province Education Department (LJKMZ20221170); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82000625); Young and middle-aged Science and Technology Innovation Talent Program (RC220482); and Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2019-MS-359).

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Drs. Ge and Hu contributed equally to this article.

Contributor Information

Nan Ge, Email: gen@sj-hospital.org.

Yue Hu, Email: huyue009@126.com.

Kai Zhang, Email: zhangkaidoctor@163.com.

Nan Liu, Email: cmu_ln@163.com.

Jitong Jiang, Email: 1873321039@qq.com.

Jianyu Wei, Email: wjy@micro-tech.com.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koizumi E, Goto O, Shinji S, et al. Feasibility of endoscopic hand suturing on rectal anastomoses in ex vivo porcine models. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Targarona EM, Balague C, Pernas JC, et al. Can we predict immediate outcome after laparoscopic rectal surgery? Multivariate analysis of clinical, anatomic, and pathologic features after 3-dimensional reconstruction of the pelvic anatomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lendzion RJ, Gilmore AJ. Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis and natural orifice surgery extraction/minimal extraction site surgery in the obese. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:1180–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki H, Ikeda K. Endoscopic mucosal resection and full thickness resection with complete defect closure for early gastrointestinal malignancies. Endoscopy. 2001;33:437–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier B, Stritzke B, Kuellmer A, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic full-thickness resection in the colorectum: results from the German Colonic FTRD Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1998–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boger P, Rahman I, Hu M, et al. Endoscopic full thickness resection in the colo-rectum: outcomes from the UK Registry. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33:852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JS, Kim B-W, Kim JI, et al. Endoscopic clip closure versus surgery for the treatment of iatrogenic colon perforations developed during diagnostic colonoscopy: a review of 115,285 patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:501–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JH, Kedia P, Stavropoulos SN, Carr-Locke D. AGA clinical practice update on endoscopic management of perforations in gastrointestinal tract: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2252–2261.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makarawo TP, Damadi A, Mittal VK, Itawi E, Rana G. Colonoscopic perforation management by laparoendoscopy: an algorithm. JSLS. 2014;18:20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchant AM, Lin E. Single-incision laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for a colon mass. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law R, Wong Kee Song LM. Closing the lid on iatrogenic colonic perforations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris MT, Laudito A, Waye JD. Colonoscopic features of colonic anastomoses. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt A, Beyna T, Schumacher B, et al. Colonoscopic full-thickness resection using an over-the-scope device: a prospective multicentre study in various indications. Gut. 2018;67:1280–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwager LW, Bastiaansen BAJ, Bronzwaer MES, et al. ; Dutch eFTR Group. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (eFTR) of colorectal lesions: results from the Dutch colorectal eFTR registry. Endoscopy. 2020;52:1014–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura T, Sugimoto S, Temma T, Oyamada J, Ito K, Kamei A. Suturing techniques with endoscopic clips and special devices after endoscopic resection. Dig Endosc. 2022;35:287–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staudenmann D, Choi KKH, Kaffes AJ, Saxena P. Current endoscopic closure techniques for the management of gastrointestinal perforations. Ther Adv Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;15:26317745221076705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiehua Z, Kashif A, YaoSheng C, YunYun S, Lanyu L. Analysis of the characteristics of colonoscopy perforation and risk factors for failure of endoscopic treatment. Cureus. 2022;14:e25677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanella G, Bronswijk M, Arcidiacono PG, et al. Current landscape of therapeutic EUS: changing paradigms in gastroenterology practice. Endosc Ultrasound. 2023;12:16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramai D, Facciorusso A, Crinò SF, Adler DG. EUS-guided gastroenteric anastomosis: a first-line approach for gastric outlet obstruction? Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:404–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossi G, Petrone MC, Vanella G, Archibugi L, Arcidiacono PG. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy in a COVID-19-infected patient with duodenal stenosing lymphoma (with videos). Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:221–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.