Abstract

Introduction

People from minoritised ethnic groups are diagnosed with dementia later in the disease. We explored pathways that may determine the timing of diagnoses in a UK ethnically diverse, urban area.

Methods

We conducted 61 semi-structured interviews: 10 community-dwelling older people from minoritised ethnic backgrounds with diagnosed and undiagnosed dementia (mean age = 72 years; males = 5/10), 30 family members (51; 10/30), 16 health or social care professionals (42; 3/15), 3 paid carers and 2 interpreters for people with dementia. We used reflexive thematic analysis and the Model of Pathways to Treatment to consider diagnostic delay.

Findings

We identified three themes: (1) Cultural identity and practices shape responses: gendered expectations that families relieve elders of household roles reduce awareness or concern when functioning declines; expectations that religious practices are maintained mean problems doing so triggers help-seeking. Second-generation family members often held insider and outsider identities, balancing traditional and Western perspectives. (2) Becoming like a tourist: daily experiences became unfamiliar for people developing dementia in an adopted country, sometimes engendering a need to reconnect with a home country. For professionals and interpreters, translating meanings faithfully, and balancing relatives’ and clients’ voices, were challenging. (3) Naming and conceptualising dementia: the term dementia was stigmatised, with cultural nuances in how it was understood; initial presentations often included physical symptoms with cognitive concerns.

Conclusion

Greater understanding of dilemmas faced by minoritised ethnic communities, closer collaboration with interpreters and workforce diversity could reduce time from symptom appraisal to diagnosis, and support culturally competent diagnostic assessments.

Keywords: dementia, diagnosis, inequalities, ethnicity, qualitative, older people

Key Points

People from minoritised ethnic groups are diagnosed with dementia later in the disease.

Greater understanding of dilemmas faced by minoritised ethnic communities.

Closer collaboration with interpreters and workforce.

We used reflexive thematic analysis and the Model of Pathways to Treatment to consider diagnostic delay.

Introduction

People typically wait >3 years from symptom onset to dementia diagnosis [1]. Timely diagnosis empowers people to understand symptoms, make plans and access symptomatic treatments [2]. Dhedhi [3] distinguished timely diagnosis, which is timed to be person-centred and beneficial, from early diagnosis, referring to a chronological stage, acknowledging criticism that early diagnosis can lead to overdiagnosis and stigma.

People living in less affluent areas and from ethnic and other minoritised groups are typically diagnosed with dementia later and with processes characterised by less accuracy [4–7]. Three percent of people currently living with dementia in the UK are from ethnic minority backgrounds [8] with the figure expected to double by 2026 and South Asian communities experiencing the steepest increase. As the dementia prevalence is set to rise in UK minority ethnic communities, there is a risk that under-capture of cases will limit understanding of community needs [9]. Studies in Norway [10, 11] and Canada [12] suggest reasons for this underdiagnosis include inappropriate attribution of symptoms to normal ageing, stigma, lack of professional knowledge regarding diagnostic tools and language barriers. Symptom attribution refers to the personal and social construction of meaning surrounding dementia, and is context dependent [13]. Associated stigma and limited culturally specific or translated materials can mean that even where awareness is increased, knowledge is not [14, 15].

Among Indian people with mild dementia and family carers in New Zealand, dementia was often attributed to ‘karma’, engendering feelings of acceptance and delaying help-seeking [16]. McCleary [12] described how South Asian family carers modified environments to account for symptoms rather than seek medical help. Families may conceal problems stigmatised within a cultural context, especially where culturally sensitive services are unavailable [17–19]. Sagbakken describes the challenge to services ‘to become familiar with each person’s way of being ill’ [20]. There is a risk that people from minority ethnic groups are positioned as culturally ‘other’ and their individual uniqueness under-recognised and that health professionals should avoid community- and culture-based stereotypes [21]. To our knowledge, only one UK published study has qualitatively interviewed people from ethnic minoritised ethnic groups affected by dementia to explore diagnostic delay. Family carers from South Asian communities described how early cognitive changes were often initially conceptualised as physical or affective changes [22].

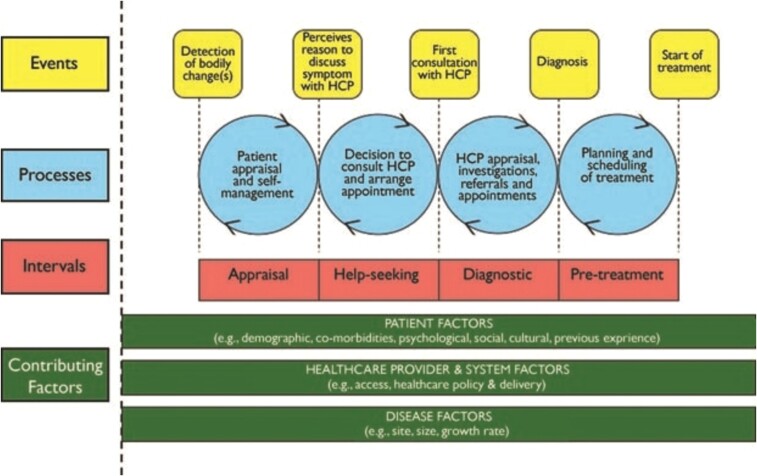

We used the Model of Pathways to Treatment [23] (Figure 1) as a theoretical framework to consider the pathways that determine the timing of dementia diagnosis in an ethnically diverse, London area. Based upon the Anderson model of treatment delay, this model encompasses existing psychological theory through Appraisal and Help-seeking intervals, previously applied to cancer diagnosis but not to dementia [24]. Dementia care pathways tend to focus upon assisting clinical diagnosis and assessment [25] rather than the psychological complexities surrounding this experience and process. The Model of Pathways to Treatment captures the psychological complexity and dynamic pathways that shape diagnosis. Its application supports our aims to understand the complex and dynamic pathways that shape dementia diagnosis and treatment delay. We included people from minoritised ethnic communities in East London, where the most common minority ethnic groups are Asian or Asian British, and Black or Black British, Caribbean or African. While experiences may differ between minority ethnic cultures, there is a common risk of being diagnosed with dementia later [6]. We sought to explore how experiences of immigration and effects of globalisation on family life and traditional kinships might explain delayed diagnosis and engagement with and by health services.

Figure 1.

Model of pathways to treatment.

Method

Study design

This qualitative, semi-structured interview study with thematic analysis was approved by Yorkshire and the Humber—Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (REC: 23/YH/0034) on 1 March 2023.

Study setting, population and recruitment

We advertised the study in East London community, health and social care settings. We recruited participants from non-statuary services and carers organisations and National Health Service (NHS) primary and secondary care organisations. We approached interpreters and professionals working within these organisations across East London who diagnosed dementia or supported people to access diagnostic services, via participating organisations and contacts of the team. We invited professionals to participate and approach their clients and family members of clients.

We purposively recruited people (aged 60+) living in East London and experiencing dementia symptoms, for diversities of culture, gender, ethnicity, disability and other experiences (migration, deprivation); and professionals, for role diversity across primary and secondary NHS care and non-statutory organisations, including professional interpreters and paid care workers. We included participants with a dementia diagnosis or symptoms (Noticeable Problems Checklist score of 5+ [26]) without a formal diagnosis. We planned our sample size to ensure sufficient diversity [27], with a priori intention to include 40–60 people.

Procedures

C.Ca., M.R. and E.W. (experienced qualitative researchers) conducted semi-structured interviews between April and September 2023 via video-call or face-to-face, as interviewees preferred. Interviews reflected the language interviewees used to describe their cognition. Interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. People with dementia were interviewed with carers if they preferred.

We consulted patient and public collaborators, the clinical and academic team to develop topic guides based around our aim (above), accounting for our theoretical framework [23] (Figure 1). They explored experiences of prodromal dementia; initial symptoms, help-seeking and, where appropriate, pathways to diagnosis.

Potential participants who expressed an interest in participating were provided with the information sheet, and after a minimum of 48 hours approached to discuss participation and where they decided to proceed, informed consent. We only interviewed participants with capacity to consent. We asked people living with dementia to consent to interviews with family and paid carers about their symptoms and care. For those who lacked capacity, we asked a personal consultee to complete a consultee declaration form around this decision, in line with the Mental Capacity Act (England & Wales), 2005. The personal consultee was the carer who took part in the interview. We added this step to ensure that the thoughts and feelings of the person with dementia were explicitly considered. They did not give consent for the person with dementia to take part as we only interviewed people who had capacity. Participants were offered a voucher as a thank you for their time and trouble.

Analysis

We used a reflexive thematic analytic approach [28], then mapped inductive themes to our theoretical framework [23] (Figure 1) to consider how they informed our understanding of diagnostic delay. We exported anonymised, professionally transcribed interviews to NVivo [29]. C.Ca./M.R. read interviews, then preliminarily coded five transcripts. Co-authors also read the transcripts and at an analysis meeting, we explored interpretations, meaning and initial codes and themes. We used manual coding to engage with the data [25], highlighting relevant text and tagging it with code labels. C.Ca. and E.W. conducted the analysis supported by the co-authors. We continued coding transcripts, iteratively developing the coding framework [19]. We drew on Braun and Clarke’s work to determine sample size and focused on recruiting a rich and diverse sample [27].

At a second analysis meeting, we presented data from 21 anonymised transcripts to a group including patient and public team members and community stakeholders, welcoming critical debate of emergent themes and new interpretations. We used these discussions to refine codes and themes, and led by our study aim, map them to intervals in our theoretical model: appraisal, help-seeking and diagnosis [23].

Findings

Recruitment

Of 15 individuals living with dementia symptoms, 36 family members, 25 health care professionals, 3 interpreters and 4 paid carers who expressed an interest in taking part, 61 were recruited. We included 10 individuals living with dementia, 9 of whom did not recall a dementia diagnosis, 30 family members, 18 of which were caring for a relative with a diagnosis of dementia, 12 did not report a diagnosis, 16 health care professionals, 2 interpreters and 3 paid carers. Reasons for not taking part included limited time due to commitments or people not responding after the initial contact and expression of interest. Sociodemographic characteristics and role characteristics for professionals are displayed in Table 1. Interviews lasted 20 to 45 min. Five interviews used professional interpreters, and in addition three family members translated where this was preferred by dyads.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Demographic | People with dementia (n = 10) | Family carers (n = 30) | Paid carers (n = 3) |

Health care professionals

(n = 16) |

Interpreters

(n = 2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity: Asian | Other | – | 2 | – | – | – | |

| Bangladeshi | 4 | 13 | – | 1 | – | ||

| British | – | – | – | 2 | 1 | ||

| Chinese | 1 | 2 | – | 1 | – | ||

| Pakistani | – | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Filipino | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Vietnamese | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | ||

| Black | African | 2 | – | – | 2 | 1 | |

| British | – | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Caribbean | 2 | 5 | 1 | – | – | ||

| Mixed/other | Bangladeshi/British | – | 2 | – | – | – | |

| Bengali/Italian | – | 2 | – | – | – | ||

| Black British (mixed) | – | – | – | 3 | – | ||

| Black Caribbean/White | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Caribbean/Vietnamese | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Somalian | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| White | British | – | – | – | 3 | – | |

| European | – | – | – | 2 | – | ||

| Sex | Female | 5 | 20 | 3 | 13 | 2 | |

| Male | 5 | 10 | – | 3 | 0 | ||

| Age | Mean (SD) in years | 72 (14) | 51 (17) | 50 (15) | 42 (9) | 39 (3) | |

| Marital status | Married/civil partnership | 4 | 17 | – | – | – | |

| Single | 3 | 11 | – | – | – | ||

| Widowed | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Divorced | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Living with | Alone | 3 | 5 | – | – | – | |

| Partner/spouse | 3 | 6 | – | – | – | ||

| Parent(s) | – | 13 | – | – | – | ||

| Children | 3 | 6 | – | – | – | ||

| Daughter-in-law | 1 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Accommodation | Council rented | – | 4 | 2 | – | – | |

| Housing association | 4 | 10 | 1 | – | – | ||

| Private rented | – | 8 | – | – | – | ||

| Owner-occupied | 5 | 8 | – | – | – | ||

| Assisted living | 1 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Education | Degree/postgraduate | 2 | 14 | – | – | – | |

| Aged 16/18+ qualifications | 2 | 12 | 3 | – | – | ||

| No formal qualifications | 6 | 4 | – | – | – | ||

| Professional roles | Nurse | – | – | – | 5 | – | |

| General practitioner | – | – | – | 3 | – | ||

| Manager | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Occupational therapist | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Psychiatrist | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Psychologist | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Geriatrician | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Therapist | – | – | – | 2 | – | ||

| Neurologist | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Dementia subtype | Alzheimer’s disease | 1 | 10 | – | – | – | |

| Vas cular dementia | – | 5 | – | – | – | ||

| Mixed dementia | – | 3 | – | – | – | ||

| Memory problems | 5 | 7 | – | – | – | ||

| Not known | 4 | 5 | – | – | – | ||

| First language | English | 5 | 14 | 1 | 10 | – | |

| Bengali | 4 | 12 | – | 1 | – | ||

| Cantonese | 1 | 2 | – | 0 | 1 | ||

| French | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Polish | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Swedish | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Vietnamese | – | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Somalian | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Tangelo | – | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| Urdu | – | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Zulu | – | – | – | 1 | – |

Qualitative findings

We identified three themes.

Cultural identity and practices shape responses: How cultural, family and religious identities and practices shape appraisal and help-seeking.

Becoming like a tourist: how, for some people, developing dementia in an adopted country engendered a need to reconnect with a home country.

Naming and conceptualising dementia: exploring how stigma, mistrust and cultural norms might affect timing of a dementia diagnosis

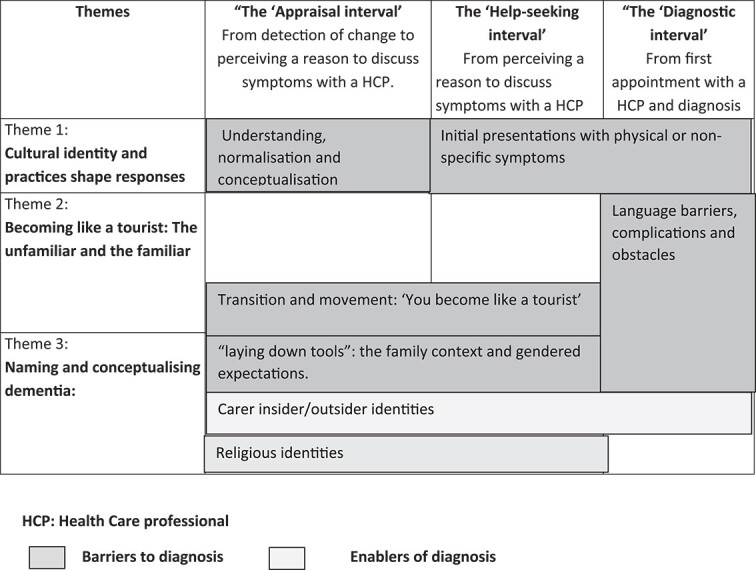

Table 2 illustrates how our themes informed our understanding of Appraisal, Help-seeking and Diagnostic intervals as related to our theoretical model.

Table 2.

How themes fit in the model of pathways to treatment framework

|

Theme 1: Cultural identity and practices shape responses

This theme represented the centrality of family context to symptom appraisal and help-seeking; family members often held insider and outsider identities, balancing more traditional values and attitudes with support from health care professionals. Gendered role expectations and religious identities shaped how families appraised difficulties and sought and provided support. Symptoms associated with dementia were equally impactful, regardless of whether the person recalled a diagnosis of dementia.

For many interviewees, being part of a traditional, often intergenerational household was central to symptom appraisal. Interviewees described how, within their local Bangladeshi community, it is considered respectful for a daughter to care for her mother and mother-in-law, even when the older person remained well: preparing food, shopping and sometimes washing and dressing. An interpreter translating for male Bangladeshi family carer referred to this relinquishing of roles by older women: ‘four years ago sister-in-law came and she’s not been cooking since.’

In this context, families sometimes did not realise that their parent had lost skills. A memory clinic nurse described this within multigenerational households:

In the Bangladeshi families the custom is that once there is a daughter in law in the household she takes over a lot of the things, so the mother or the person who is being assessed and if it’s a female, it’s almost an expectation that she would lay down her tools and let the young ones get on with things and that can be disabling for people, even though it’s a choice to do it. It means that, it’s difficult for us to know whether the person still can. (Memory clinic nurse, female, Black African)

Another nurse commented on the challenges of working with families where caring is perceived as a female, and liaising with health care professionals a male role:

You ask them, “Well, do you look after mum or dad and stay with them?” And they look at you and say, “Of course I don’t,” it’s like… or, “My wife.” And it’s like, “Well, could I speak to them?” And a lot of the time, the answer is yes, but not completely, sometimes “You cannot speak to a female in my family.” (Male consultant liaison nurse, White British)

Family members who were born in Britain to immigrant parents described inhabiting insider/outsider cultural identities, navigating a process of seeking help within a Western healthcare system that is sensitive to their parents’ or families’ cultural and ethnic background. This family carer relates her experiences of appraising when to seek help to living in an area with low ethnic diversity and how symptoms appear to be minimised:

I think because I’m their only child. So, me repeatedly saying something, you could class me as a community because where we live is a predominantly white area. We don’t live in an Asian area. So, if we did, there’s a thing of like other people would have noticed it, then it might have been more of a laughing talking point, “Uncle’s doing this again,” whatever’s doing it. It’s more of a joke. (Female family carer, no dementia diagnosis, Bangladeshi)

Cultural and religious expectations that caring was virtuous and duty-bound were inherent in accounts. The same family carer explained how people in her community did not identify with the label of carer since ‘if you label it, you’re failing’, and this may be an obstacle to accessing support. We observed religious practices as both a barrier and potentially a facilitator to help-seeking. Changes in religious practice often triggered recognition of a cognitive concern and a response. We heard examples of this within the Muslim community in relation to prayer and using the Quran, and within the Caribbean community when older members of the church community were unable to take part as independently as previously. The emotional impact of reduced ability to perform and observe religious roles is evident in the following account from a father, who chose for his daughter to translate:

So, he’s saying the fact he forgets, and especially when it comes to prayers, so you have certain times you have to do it, and he forgets whether he’d done it. So he performs it again, then when he’s performing, he makes mistakes as well, so he kind of, he remembers, did I say the specific verse? Then it’s a vicious circle he’s in, so he’s quite muddled in his brain, that’s what he said. (Male diagnosed with dementia, Bangladeshi)

When to pray, order of prayers and Quranic verses are learnt in childhood, so to forget was an indicator of cognitive loss, which impacted an individual’s role and identity. Religion also affected the appraisal of a situation as the following account illustrates.

I’ve seen, and I’ve heard patients talk about their religious beliefs. So that’s kind of also, I would say, a barrier to them reporting symptoms because they think, they believe, that whatever they’re experiencing is related to Allah, kind of directing or giving this to them, and therefore it’s Allah who will heal them, or will help them through this. (Occupational therapist, female, Filipino)

Theme 2: ‘You become like a tourist’ immigration experiences and language barriers

This theme encompasses areas linked to familiarity: how experiences and cultural practices that are familiar can become unfamiliar through dementia and how language barriers can become more disabling when dementia symptoms also challenge communication. It includes examples of people travelling back to a country of origin as part of a family’s response to cognitive concerns. Narratives about movement and travelling were identified across a number of accounts. These were arranged by members of the family members, usually adult children, and all involved travel to a country from which their parents originated, to appraise or seek help for dementia symptoms, with the following quotation illustrating this:

Yeah, because she wasn’t all that, so I said, “Let me take her to the Caribbean to see if she’s going to be the same. She (Mum) was OK for a while, then she started the same thing/pattern again”. (Female family carer, no dementia diagnosis, Black Caribbean)

Appraising changes following travel to the home country appears to happen regardless of a relative having a dementia diagnosis.

She said that before she can feel that his memory gone but it’s not strong like now. Before that he went to the hospital and they got an ear test done. But since he came back from Vietnam that is where she knew that he lost his memory. (Wife of man with dementia diagnosis, Vietnamese)

There were examples of first-generation individuals expressing a desire to return ‘one more time’ to a homeland, when they recognised that their memory was becoming worse. One participant described feeling like a ‘tourist’ due to memory problems after having lived in the UK for 50 years. He felt disorientated in a usually well-known location, which in the interview he compared to his early experience of unfamiliarity after arriving in the UK.

I have been living for long here but when this started I become like a stranger, like I just come to this country, now, if I go to the train station, I have to look at the map, you become a tourist. (Man with dementia, Caribbean background)

A manager of a centre described how important trust was to older people from the Caribbean community, suggesting that the yearning for home country might also be met through availability of specific cultural social resources.

They trust us. They trust us, and they could see how we are with their family members. And as I said, we go above and beyond to help and engage with them. And I think they probably need more out there. More, yes. (Manager, female Black Caribbean)

Language differences created challenges for people with dementia, their families and health care professionals to ensure that information is accessible, and concerns and needs are voiced, heard and understood. Translation may not convey meaning, and professionals and interpreters described challenges in balancing voices of relatives and clients. A general practitioner (GP) described the challenges of translating not only words but meaning:

The translation of the word dementia, when I say to the interpreter, can you tell this person they have dementia. I'm not really sure how, I am describing it and dementia means that. I am getting those bits translated but the word in itself, I'm not convinced that there is a word, I'm not convinced that there is a selective word that completely is a direct translation. (Consultant psychiatrist, male, White British)

There was a sense in several accounts of a ‘double jeopardy’ of communication barriers for people with dementia accessing healthcare via an interpreter, especially where accompanying relatives are able to engage directly with professionals in English. A family carer (female, Bangladeshi) stated that both her parents had symptoms consistent with dementia but only her father had a diagnosis, and she attributed this to his ability to speak English, while her mother did not. She felt that there was a difference in how they were heard and felt that the translator was not conveying everything reliably from her mother to the doctor in the memory clinic:

I mean, my personal view is, if you can speak English well, you have one service. If you can’t, you have a totally different one. (Daughter and carer, diagnosed with dementia Bangladeshi)

In the example below, a son felt his mum was repeating things or ‘telling too many stuff’ and therefore intervened through translating parts of the exchange. Due to the absence of a diagnosis, this possibly effects the son seeing it as a symptom of dementia.

No, she doesn’t go out, so basically even with an interpreter sometimes we still need to help her when she is seeing the doctor, she doesn’t remember, or she keep repeating. Or she probably telling too many stuff at the same time. We have to assist her even with the interpreter, she is fully dependent on us. (Male family carer, no dementia diagnosis, Bangladeshi background)

Health care professionals described challenges accessing professional interpreters, leading to use of telephone interpreting services. One GP felt this increased the risk of misunderstandings, as non-verbal cultural nuances were lost.

Theme 3: Naming and conceptualising dementia

In this theme, we discuss how the term dementia was stigmatised and there were cultural nuances to how it was understood. This theme held relevance across the three stages of our conceptual model—appraisal, help-seeking and diagnostic intervals.

Cognitive symptoms were the primary trigger for help-seeking for the majority of the people living with dementia and family carers that we interviewed; however, other symptoms were present and were a trigger for help-seeking for some. Health care professionals described how consultations with reoccurring physical concerns such as mobility pains and arthritis could mask dementia symptoms, extending the diagnostic interval. Several GPs interviewed described this, including the quotation below:

They do come with vaguer symptoms sometimes, like it’s often—yes, actually, I guess when they’re coming indirectly, it’ll be repeated appointments for the same thing, or sort of a preoccupation with an arthritic knee, something just coming again and again, and eventually, and you think, “Well, something’s not right here.” …. I had one patient like that, and it did take me a while for the penny to drop. (GP, female, described herself as mixed background)

Families also often sought help in this way, attributing behavioural or cognitive changes to physical illness, or sought help for their relative’s physical health problems, because they did not feel able to name cognitive symptoms, as in this quote:

So they won’t have been told it’s because of a memory problem that they’re coming to see the doctor. They’ll have been told you’re coming about the cough that you’ve had, or whatever it is, So then they want to tell you about that, and that’s why it’s like shh, shh, no don’t worry they’re just trying to tell you about the cough they’ve got. And it’s—so it will be brought under like under sort of false pretences to come and see me. (GP, female, white British)

A neurologist attributed initial presentations often including physical symptoms with cognitive concerns to a reluctance to address mental health issues, including cognitive concerns, which as the quote below illustrates, could extend the appraisal and help-seeking intervals:

From personal experience as an Asian person with an Asian family, I know that there is a huge emphasis on physical health, and it’s very, very difficult, I think, to talk to people about mental health, and even the idea that it could have aspects impact on physical health. So I don’t think it’s that the patients biologically are obviously presenting differently, I think it’s that it's what they are noticing and wanting to seek help for is different, and similarly, what their family are noticing and wanting to seek help for is different. (Consultant neurologist, male, Sri Lankan)

Many accounts described the terms dementia and forgetfulness being used interchangeably, with an implication that dementia is a normal part of ageing, but this was culturally specific. These included an account from a daughter caring for her father, from a Bangladeshi background, who commented about dementia: ‘essentially, it’s forgetting’. This Vietnamese interpreter described how cultural norms influenced how she translated during diagnostic appointments:

The translation for dementia in Vietnamese is very … basically, you’re forgetful, they don’t use that word “dementia”. (Female interpreter in memory clinic, Vietnamese)

Several interviewees described mild dementia as ‘forgetting’, while reserving the term dementia for severe dementia. A GP observed that patients reserved the term dementia for severe cognitive impairment, while mild or even moderate dementia was not accepted as such:

I think because I am from Trinidad it is fair for me to talk about it, so the patients I would be able to say to them, yes I get it, I get what you see as dementia. I know what dementia means when you are in the Caribbean, I don’t know how to phrase this in a correct way, but really completely lost all their cognitive functions, is what they see dementia as. (GP, female)

These appraisals potentially extended the help-seeking interval. Many interviewees described discomfort with the word dementia; one female Bangladeshi family carer referred to dementia and mental illnesses such as depression as being ‘taboo’, particularly for the older generation: ‘Mental health is taboo. You just don’t talk about it at all’.

This seemed to reflect shame around cognitive decline, poor mental health and dementia, which, although rarely voiced by patients or family carers, was referred to by professionals, including in this extract:

Different groups might feel less trust for health professionals and obviously going to the GP about your memory is really exposing. And there is lots of fears of stigma and not being taken seriously and even having your rights removed and what’s going to happen if I open up about this for myself. (GP, female, White British)

A family carer also linked reluctance to seek help and get a diagnosis to trust, commenting:

If you don’t really recognise/understand dementia conceptually and there is a stigma in it, then why would you seek help? (Family carer, female, no dementia diagnosis, Bangladeshi)

Another also linked an extended help-seeking interval to low expectations of the dementia care they would receive and an absence of a ‘mental model’ of help-seeking:

And there isn’t a preventable attitude in the countries that don’t have a free healthcare system. If you’ve come from somewhere that doesn’t have social services, doesn’t have a free healthcare system, you are not going to get intervention because you have to pay for it. So, you don’t have a natural mental model to go. (Female family carer, dementia diagnosis, Bangladeshi)

Discussion

We aimed to explore the complex pathways that determine timing of dementia diagnoses in an area of high ethnic density, to understand how services might be more culturally competent. We used the Model of Pathways to Treatment [23] to understand the multifaceted contexts in which people may or may not seek help, and the dynamics around giving and receiving a dementia diagnosis within diverse communities. We identified three themes responding to our aim. They explore how cultural identity and practices shape responses to dementia symptoms, with second-generation family members often balancing Western care systems with traditional values and attitudes, including expectations around gender and religious practice [30]. The onset of dementia held challenges for first-generation immigrants, sometimes engendering a need to reconnect with a home country. For those for whom English was a second language, linguistic and dementia-related communication barriers could cause a ‘double jeopardy’ in terms of communicating with health and care providers [31]. Interpreters described the challenges in translating meanings as well as words, and balancing relatives’ and clients’ voices. Discourses around stigma were evident in accounts, with this and feelings of mistrust in services proposed to explain the common observation that initial help-seeking was often for physical symptoms.

Our themes were relevant to the appraisal interval of the Model of Pathways to Treatment [23] (Figure 1 and Table 2). This posits that people consult a health care professional when they believe something is wrong or serious, or interfering with their functioning and beyond their ability to cope. We included people without a dementia diagnosis, to capture the views of those who remained at the appraisal stage of help-seeking, without seekingje help.

Our findings echo previous reports that in South Asian communities, ceding household duties to a daughter-in-law meant loss of such skills was not considered problematic [22, 32]. By contrast, decline in religious practice often indicated to families that help was needed. This was reported by Muslim and Christian participants and is not, to our knowledge, previously discussed in the literature. Notions of karma have been cited to explain how Hindu participants understood and responded, with acceptance to dementia [16, 20].

Scott et al. [23] discuss how expectations of whether services will reassure, help symptoms or improve prognosis can influence the duration of ‘appraisal’ and ‘help-seeking’ intervals. Negative expectations of unwanted treatment, investigations, embarrassment or disruption to self-esteem, self-identity or sense of independence delay help-seeking. For many interviewees, stigma delayed help-seeking, with presentations with physical rather than cognitive symptoms, due to embarrassment. Among minority ethnic carers in England, stigma and mistrust of services, and beliefs that physical illnesses, feigning or life changes were causing dementia symptoms are previously cited as reasons for delayed presentation [22]. Unlike in this previous study, our findings suggested that presentations with physical symptoms were strategies to raise cognitive concerns despite stigma, rather than due to a lack of attribution to dementia.

We identified the insider/outsider roles held by family carers as enabling help-seeking and obtaining a diagnosis. Family carers from Bangladeshi and Indian ethnic backgrounds in England have described wanting to be supported by services, but encountering unacceptable care models, and tensions between expectations of first-generation parents and their other, work and family roles [33]. Previous research has not distinguished between experiences in areas of high versus low ethnic diversity: one family carer participant felt her situation would be different in an area with higher ethnic density if she was supported by a larger local community. According to social cognitive theory, social contacts influence when and whether an individual decides to seek care [23]. Similarly, more adverse mental health outcomes are reported in areas with low ethnic diversity, where exclusion from local networks, geographically dispersed culturally specific services and more damaging effects from everyday racism are reported [34]. Perhaps this needs to consult trusted social contacts explained why some people developing dementia and their families wanted to return to a home country as part of their symptom appraisal.

While others have discussed the importance of biographical narratives within contexts of migration and associated stigma [14, 15, 21, 32], the concept of feeling ‘like a tourist’ has not, to our knowledge, been described previously. This novel finding builds on related work: Roche describes a similar theme denoting a state of precarity in the sense of belonging and social position Black African and Caribbean people with dementia experience in UK [35]. Johl likened migration to ‘repositioning of existence’ and caring for a family member with dementia as a further repositioning that may echo previous geographical translocations [32].

Previous authors have described a need for ethnic and language matching between interviewers and participants in research in minority ethnic communities to elicit trust and shared understanding [36]. Interviewers in this study had different ethnic backgrounds (Black Caribbean and White British) to interviewees. Qualitative studies of this nature risk unintentionally ‘othering’ minoritised ethnic groups. Our intention was not to compare minoritised ethnic communities to other groups, but to understand why people from minoritised ethnic groups receive dementia diagnoses later, and how services could account for styles of appraisal and help-seeking to reduce this inequality. For example, the belief that dementia is part of normal ageing may be no more common in minoritised ethnic than majority ethnic populations [15]. Normalising bodily changes saves cognitive effort and allows functioning to continue [37]; as people grow older, they increasingly attribute sensations to ageing rather than illness [38]. Individuals across all cultures who are embarrassed, frightened or ashamed by symptoms will commonly delay seeking help [39]. Parker reflects on the role of normalisation behaviours in protecting people living with dementia from risks of disempowerment [17]. Our finding that fear of stigma and a sense of alienation from services in first-generation immigrants might underlie these processes for some minoritised people can inform interventions to reduce inequalities.

This is, to our knowledge, the first qualitative study exploring how people from ethnically minoritised communities seek help for dementia symptoms, to include perspectives of people with undiagnosed dementia and interpreters. Appraisal and help-seeking were influenced by complex cultural and religious responses, including wishes rooted in migratory histories to revisit home countries.

Complexities of translating and interpretation sometimes delayed diagnosis. Previous studies, which interviewed health care professionals but not interpreters, described difficulties assessing dementia due to language barriers, including interpreters changing sentences or meanings to facilitate translation and thus introducing errors [10].

Limitations

The range of stakeholders we recruited was a strength. Individuals who self-selected to participate may have had enhanced awareness of dementia symptoms and access to services.

Conclusion

Parker has advocated for a wider societal approach, including dementia-friendly communities, to support and empower in the pre-diagnosis period while deciding when to seek help [17]. More minority ethnic and culturally competent staff in dementia services and dementia training for interpreters [15] would enable support that continued that ethos into the diagnostic period. Clinicians should consider strategies to raise cognitive impairment sensitively in different cultures [10]. Perhaps for some communities, religious activities, rather than household tasks, for which families compensate for functional decline with collectivistic approach to support and care [10], are a helpful focus when exploring functioning.

Clinicians and interpreters should plan how to convey a diagnosis and key information collaboratively, acknowledging that will take longer than where interpretation is not required. Clinicians might usefully consider the cultural variations of symptom attribution, including the normalisation of cognitive health concerns through role and cultural beliefs.

Contributor Information

Christine Carter, Queen Mary University of London Wolfston Institution of Population Health—Centre for Psychiatry and Mental Health, Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Yvonne Carter House, London E1 2AD, UK.

Moïse Roche, UCL—Division of Psychiatry, London, UK.

Elenyd Whitfield, Queen Mary University of London Wolfston Institution of Population Health—Centre for Psychiatry and Mental Health, Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Yvonne Carter House, London E1 2AD, UK.

Jessica Budgett, Queen Mary University of London Wolfston Institution of Population Health—Centre for Psychiatry and Mental Health, Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Yvonne Carter House, London E1 2AD, UK.

Sarah Morgan-Trimmer, University of Exeter Medical School, Health and Community Services Exeter, UK.

Sedigheh Zabihi, Queen Mary University of London Wolfston Institution of Population Health—Centre for Psychiatry and Mental Health, Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Yvonne Carter House, London E1 2AD, UK.

Yvonne Birks, University of York—Social Policy Research Unit, Heslington, York, North Yorkshire YO10 5DD, UK.

Fiona Walter, Queen Mary University of London Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry—Wolfson Institute of Population Health, London, Charter House Square EC1M 6BQ, UK.

Mark Wilberforce, University of Exeter Medical School, Health and Community Services Exeter, UK.

Jessica Jiang, UCL—Dementia Research Centre, London WC1N 3BG, UK; UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK.

Refah Ahmed, East London NHS Foundation Trust Ringgold standard institution—Academic Centre Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry Centre for Mental Health, London, UK.

Wesley Dowridge, Queen Mary University of London Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry—Wolfson Institute of Population Health, London, Charter House Square EC1M 6BQ, UK.

Charles R Marshall, Queen Mary University of London Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry—Wolfson Institute of Population Health, London, Charter House Square EC1M 6BQ, UK.

Claudia Cooper, Queen Mary University of London Wolfston Institution of Population Health—Centre for Psychiatry and Mental Health, Wolfson Institute of Population Health, Yvonne Carter House, London E1 2AD, UK.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This work is funded by the NIHR Three Schools’ Dementia Research Programme Call 2022. C.R.M., C.C. and Y.B. are funded by the NIHR Dementia and Neurodegenerative Diseases policy unit at Queen Mary (DeNPRU-QM) (NIHR206110). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- 1. ARUK . Dementia Statistics [Internet]. Alzheimer's Research UK, 2022, [cited 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://dementiastatistics.org/about-dementia/.

- 2. Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor JP. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350:h3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dhedhi SA, Swinglehurst D, Russell J. ‘Timely’ diagnosis of dementia: what does it mean? A narrative analysis of GPs’ accounts. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsoy E, Kiekhofer RE, Guterman ELet al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in timeliness and comprehensiveness of dementia diagnosis in California. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:657–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jitlal M, Amirthalingam GNK, Karania Tet al. The influence of socioeconomic deprivation on dementia mortality, age at death, and quality of diagnosis: a nationwide death records study in England and Wales 2001-2017. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;81:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pham T, Petersen I, Walters Ket al. Trends in dementia diagnosis rates in UK ethnic groups: analysis of UK primary care data. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:949–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White L, Ingraham B, Larson Eet al. Observational study of patient characteristics associated with a timely diagnosis of dementia and mild cognitive impairment without dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:2957–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alzheimer’s Society . Alzheimer’s Society Report [Internet]. Alzheimer's Society UK, 2022, [cited 2002 Sep 19]. Available from: https://arc-em.nihr.ac.uk/research/explore-our-research/what-works-well-people-ethnic-minority-groups-dementia.

- 9. Mukadam N, Marston L, Lewis Get al. Incidence, age at diagnosis and survival with dementia across ethnic groups in England: a longitudinal study using electronic health records. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:1300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sagbakken M, Spilker RS, Nielsen TR. Dementia and immigrant groups: a qualitative study of challenges related to identifying, assessing, and diagnosing dementia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Czapka EA, Sagbakken M. “It is always me against the Norwegian system.” barriers and facilitators in accessing and using dementia care by minority ethnic groups in Norway: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCleary L, Persaud M, Hum Set al. Pathways to dementia diagnosis among south Asian Canadians. Dement Lond Engl. 2013;12:769–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kirmayer LJ, Young A, Robbins JM. Symptom attribution in cultural perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39:584–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adamson J. Awareness and understanding of dementia in African/Caribbean and South Asian families. Health Soc Care Community. 2001;9:391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parveen S, Peltier C, Oyebode JR. Perceptions of dementia and use of services in minority ethnic communities: a scoping exercise. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:734–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krishnamurthi RV, Dahiya ES, Bala Ret al. Lived experience of dementia in the New Zealand Indian community: a qualitative study with family care givers and people living with dementia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parker M, Barlow S, Hoe Jet al. Persistent barriers and facilitators to seeking help for a dementia diagnosis: a systematic review of 30 years of the perspectives of carers and people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;6:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stigma and Dementia: East European and South Asian Family Carers Negotiating Stigma in the UK - Jenny Mackenzie. Sage Journals UK, 2006, [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 13]. Available from: 10.1177/1471301206062252. [DOI]

- 19. La Fontaine J, Ahuja J, Bradbury NMet al. Understanding dementia amongst people in minority ethnic and cultural groups. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:605–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sagbakken M, Ingebretsen R, Spilker RS. How to adapt caring services to migration-driven diversity? A qualitative study exploring challenges and possible adjustments in the care of people living with dementia. PloS One. 2020;15:e0243803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jutlla K. The impact of migration experiences and migration identities on the experiences of services and caring for a family member with dementia for Sikhs living in Wolverhampton. UK Ageing Soc. 2015;35:1032–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mukadam N, Cooper C, Basit Bet al. Why do ethnic elders present later to UK dementia services? A qualitative study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:1070–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scott SE, Walter FM, Webster Aet al. The model of pathways to treatment: conceptualization and integration with existing theory. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18:45–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walter F, Webster A, Scott Set al. The Andersen model of total patient delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17:110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saragosa M, MacEachern E, Chiu Met al. Mapping the evidence on dementia care pathways – a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levin E. Noticeable problems checklist. London Natl Inst Soc Work. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13:201–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–97. [Google Scholar]

- 29. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software v12 . USA: QSR International, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ahmed S, Hughes J, Davies Set al. Specialist services in early diagnosis and support for older people with dementia in England: staff roles and service mix. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:1280–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cooper C, Rapaport P, Robertson Set al. Relationship between speaking English as a second language and agitation in people with dementia living in care homes: results from the MARQUE (managing agitation and raising quality of life) English national care home survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;33:504–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johl N, Patterson T, Pearson L. What do we know about the attitudes, experiences and needs of black and minority ethnic carers of people with dementia in the United Kingdom? A systematic review of empirical research findings. Dementia. 2016;15:721–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herat-Gunaratne R, Cooper C, Mukadam Net al. ‘In the Bengali vocabulary, there is no such word as care home’: caring experiences of UK Bangladeshi and Indian family carers of people living with dementia at home. Gerontologist. 2020;60:331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Whitley R, Prince M, McKenzie Ket al. Exploring the ethnic density effect: a qualitative study of a London electoral ward. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2006;52:376–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roche MM. Exploring and Meeting the Needs of Black African and Caribbean Older People with Dementia and their Family Carers: A Qualitative Study [Internet] [Doctoral]. Doctoral thesis. UCL (University College London), UCL Library Repository, 2023[cited 2023 Sep 22], i–298. Available from: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10163628/. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Victor CR, Zubair M, Martin W. Families and caring in south Asian communities. In: The New Dynamics of Ageing: Volume 2 [Internet], 2018[cited 2023 Dec 23]. Policy Press, policy.bristoluniversitypress, 87–104. Available from: https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/display/book/9781447314813/ch006.xml. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bradley EJ, Calvert E, Pitts MKet al. Illness identity and the self-regulatory model in recovery from early stage gynaecological cancer. J Health Psychol. 2001;6:511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diefenbach MA, Leventhal H. The common-sense model of illness representation: theoretical and practical considerations. J Soc Distress Homeless. 1996;5:11–38. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Turris SA, Finamore S. Reducing delay for women seeking treatment in the emergency department for symptoms of potential cardiac illness. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34:509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]