Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a risk factor for drug-induced arrhythmias. It is unknown whether HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) also increases the risk.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine if the risk of ventricular tachycardia (VT) and sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is increased in patients with HFpEF prescribed dofetilide or sotalol.

Methods

Using Medicare claims and pharmacy benefits from 2014 to 2016, we identified patients taking dofetilide or sotalol and non-dofetilide/sotalol users among 3 groups: HFrEF (n = 26,176), HFpEF (n = 33,304), and no HF (n = 580,249). Multinomial propensity score matching was performed. We compared baseline characteristics using Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel statistics and standardized differences, and tested associations of VT and SCA among dofetilide/sotalol users and those with HFpEF, HFrEF, or no HF using a generalized Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

VT and SCA occurred 166 (10.68%) and 16 (1.03%) of 1,554 dofetilide/sotalol users with HFpEF, 543 (38.76%) and 40 (2.86%) of 1,401 dofetilide/sotalol users with HFrEF, and 245 (5.06%) and 13 (0.27%) of 4,839 dofetilide/sotalol users without HF. Overall VT risk was increased in HFrEF and HFpEF patients (HR: 7.00 [95% CI: 6.10-8.02] and 1.99 [95% CI: 1.70-2.32], respectively). The risk of VT in patients prescribed dofetilide/sotalol was increased in HFrEF and HFpEF patients (1.53 [95% CI: 1.07-2.20] and 2.34 [95% CI: 1.11-4.95], respectively). While the overall SCA risk was increased in HFrEF and HFpEF patients (5.19 [95% CI: 4.10-6.57] and 2.53 [95% CI: 1.98-3.23], respectively), dofetilide/sotalol use was not associated with an increased SCA risk.

Conclusions

In patients with HF who are prescribed dofetilide or sotalol, the risk of VT, but not SCA, was increased.

Key words: drug-induced, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, sudden cardiac arrest, ventricular tachycardia

Central Illustration

Torsades de pointes (TdP) is a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) associated with QT interval prolongation. TdP can cause sudden cardiac arrest (SCA).1 More than 200 medications can cause QT prolongation/TdP, including commonly prescribed antimicrobials, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiarrhythmics, and many others.1 Heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is an independent risk factor for drug-induced TdP. Patients with HFrEF demonstrate enhanced sensitivity to drug-induced QT lengthening.2 Guidelines recommend enhanced electrocardiogram monitoring or avoidance of QT-prolonging drugs in patients with HFrEF.3,4

At least 50% of patients with HF have preserved ejection fraction.5 QT prolongation is predictive of diastolic dysfunction6 and is associated with an increased risk of arrhythmic death or resuscitated cardiac arrest.7 QT intervals are longer in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those without HF.8 Patients with HFpEF demonstrate enhanced response to drug-induced QT lengthening9 and are at increased risk of drug-induced QT prolongation compared to patients with normal ventricular function.10 However, it remains unknown whether patients with HFpEF are at increased risk for drug-induced TdP and/or SCA.

About 40% to 50% of patients with HFpEF have atrial fibrillation,5 for which the antiarrhythmic agents dofetilide and sotalol are used commonly.5 Dofetilide and sotalol cause TdP in 0.8% to 1.3%11,12 and 1.7% to 3.6%13,14 of patients, respectively, with an increased risk in those with HFrEF.15,16 Assessment of the potential for enhanced risk of proarrhythmia and SCA in patients with HFpEF is important.

We tested the hypothesis that patients with HFpEF are at increased risk for drug-induced VT and SCA compared to patients who do not have HF.

Methods

Data source

Our population consists of a nonrandom sample of 1 million Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries from pharmacies that provided appointment-based model medication synchronization programs and were identified by the Research Data Assistance Center, which provides assistance to academic, government, and nonprofit organizations or researchers using Medicare data sets. We used the National Provider Identifier for these pharmacies to request data from the Research Data Assistance Center. We adhered to the reporting guidelines for cohort studies provided by the Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology project.17 This study was considered exempt by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board.

The chronic conditions warehouse data sets consist of Medicare FFS institutional and noninstitutional claims. The cohort included Medicare claims data (Parts A, B, and D) from deidentified patients from January 2014 to December 2016. These data do not include death records. The Master Beneficiary Summary File was used to obtain baseline characteristics including age, sex, race, residence, geographical location, and enrollment information. Number of hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and emergency department visits were obtained through the Part B carrier file, Part A and Part B outpatient file, and Part A and Part B inpatient data sets. Medications were identified through Medicare Part D claims, including drug names and days of supply. Overlapping days of supply (<0.01% in Part D claims) prescriptions were adjusted using a drug adherence calculation algorithm.

Study population

Patients ≥18 years old diagnosed with HFpEF or HFrEF and those without a history of HF were included. Patients with overlapping diagnoses of HFrEF and HFpEF, <365 days of continuous enrollment in Medicare FFS, missing diagnosis code(s), and missing values for age, sex, or ethnicity were excluded.

Supplemental Figure 1 displays the flow of patient selection. Beneficiaries were required to have at least 365 days of continuous Medicare Part A, Part B, and Part D enrollment in FFS medical and pharmacy benefits. To ensure data set integrity, patients having claims and drug-using records but without any diagnosis code were removed. Patients with missing demographic records and those <18 years old were deleted. To identify patients with HFpEF, HFrEF, and patients without a history of HF, we extracted the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 Clinical Modification codes from home health, skilled nursing facility, inpatient claims, and outpatient and carrier claims (Supplemental Table 1). Patients having overlapping diagnoses of HFrEF and HFpEF were removed. Patients with cardiovascular-related visits, noncardiovascular-related visits, and comorbidities were also identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 Clinical Modification codes.

Baseline characteristics

Data collected included demographics (age, sex, race, geographic region, residential area), comorbidities (arrhythmias, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), health care utilization before the index date (cardiovascular-related emergency visits, cardiovascular-related inpatient visits, cardiovascular-related inpatient stays >5 days, cardiovascular-related outpatient visits, noncardiovascular-related emergency visits, noncardiovascular-related inpatient visits, and noncardiovascular-related outpatient visits), drug history before the index date (drugs known to cause TdP, using >1 drug known to cause TdP, using drugs with a possible risk of TdP, using drugs with a conditional risk of TdP),18 calcium channel blockers, loop and thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, digoxin, and aldosterone receptor antagonists.

Age >65 and <80 years of age were grouped into 5-year increments (≤65, 66-70, 71-75, 76-80, and >80 years). Sex was categorized as female or male. Race was categorized as White, Black, or other. Geographic region and residential area were grouped by people living in the Midwest, Northeast, South, West, and other U.S. territory; people residing in rural, urban, urban-metro adjacent, and metro, respectively. The missing residential area (0.2%) was replaced with the most frequent residential area and standardized mean differences (SMDs) of all the baseline characteristics were checked. Other missing demographic (<0.01%) information was removed. To avoid perfect separation, we defined comorbidities of cardiac arrhythmia using different ICD-9 and 10 Clinical Modification codes (Supplemental Table 2). Health care utilization and drug use history before the index date were defined as yes and no. For prescriptions, we excluded ophthalmic ointment and epidermal use. We included nonparametric frequency-matched patients who did not take dofetilide or sotalol for the purpose of selecting as many samples as possible while having similar characteristics as those who used dofetilide or sotalol. As a result, preindex (6 months before the index date) characteristics that were relevant to drug use were used for matching (age, sex, race, disease groups, patients who have cardiovascular-related emergency department visits, cardiovascular-related hospitalization, and cardiovascular-related outpatient visits).

Exposure, outcomes, and covariates

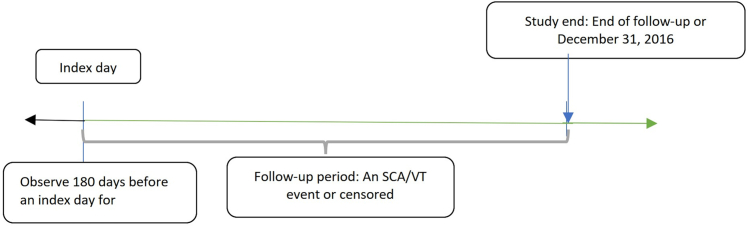

Primary outcome measures were: 1) VT; and 2) SCA. Baseline risk was defined as the day patients started to take medication. The endpoints were determined by ICD-9 (VT: 427.1; SCA: 427.5) and ICD 10 (VT: I47.2; SCA: I46.9) codes. Because each patient may have had multiple endpoints in this data set, a data structure that incorporated time-variant and time-invariant covariates was developed for capturing the longitudinal aspect of outcomes.19 The first day that a dofetilide or sotalol prescription was filled was designated as an index date and follow-up began on that day. Patients were continuously observed unless they encountered an endpoint or were censored. Figure 1 shows the study design.

Figure 1.

Study Design

Index day: 1) First day taking dofetilide or sotalol; 2) the index days of patients not taking dofetilide or sotalol were randomly assigned based on the year and the month of patients taking dofetilide or sotalol. Baseline covariates were observed 180 days before an index date. The follow-up begins after the index date immediately. The observation periods when patients were not taking dofetilide or sotalol were also counted and adjusted as an intraperson time-variant variable. Censored events are defined: 1) Lost to follow-up (not continuously enrolled in medicare in the following year); or 2) discontinuing dofetilide or sotalol; or 3) starting using dofetilide or sotalol; or 4) December 31, 2016 SCA = sudden cardiac arrest; VT = ventricular tachycardia.

All analyses used per-protocol or on-treatment approach unless specified otherwise. If a patient discontinued dofetilide or sotalol, the event was defined as censored. We started patient observation from the first day of discontinuation of medication to the day that they restarted dofetilide or sotalol. Observation periods when patients were not taking medications were also counted and adjusted as an intraperson time-variant variable. The observation period ended when patients were lost to follow-up (not continuously enrolled in Medicare in the following year) or end of study (December 31, 2016). Concomitant drug use during the 30-day intervals was evaluated and treated as a time-variant covariate.

Statistical analysis

Normality of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Baseline characteristics summarized with percentages were compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, and those with continuous values were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test to account for non-normal distribution. Unadjusted 2-year incidence rates for VT and SCA were calculated. The unadjusted cumulative incidence rate, number of recurrent events, incident rate to the number of events, and the median (IQR) time to a specific number of events were calculated. The multinomial propensity score method was used to reduce baseline differences in the risk of VT and SCA by including various potential covariates (patient demographics, comorbidities, health care utilization, and drug history) between the HFrEF, HFpEF, and no HF groups.20 Multinomial logistic modeling was used to generate conditional probability for each patient, and inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to generate a similar distribution in which more weights were assigned to smaller groups.20 After propensity score calculation, we created SMDs and a probability distribution graph to assess the performance of the propensity score generated by multinomial logistic regression. In addition to time-dependent variables, any characteristics with SMDs larger than 0.1 were incorporated into the final model for double adjustment.21 For dofetilide or sotalol users, we included the time of drug discontinuation, and we controlled the intraperson discontinuation, meaning that the classification is maintained but adjusted by the model, which takes into account the time at which patients discontinued the drug. The generalized Cox proportional hazard model with recurrent event effect was performed to test the association between VT and SCA among dofetilide/sotalol users, HFpEF, HFrEF, and patients without HF. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Data and AI Solutions).

Sensitivity analyses

In our main sensitivity analysis, we mimicked the intent-to-treat method by grouping patients into nonuser and user, regardless of their medication-taking behavior until the end of the observation period (the event was not censored after discontinuation of dofetilide or sotalol). The second sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding patients who did not have two full years of observation. The intent-to-treat assumption was also examined in this step. Finally, a subgroup analysis was conducted including only individuals who used dofetilide or sotalol to assess the risk of VT/SCA among patients with HFrEF and HFpEF versus no HF.

Results

Patient cohort selection

There were 639,729 patients eligible for the final analysis, including 33,304 with HFpEF (1,554 patients identified as using dofetilide or sotalol after the index date), 26,176 with HFrEF (1,401 patients using dofetilide or sotalol after the index date), and 580,249 without HF (4,839 patients using dofetilide or sotalol after the index date). Baseline characteristics were significantly different across the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Cohort Baseline Characteristics (N = 639,279)

| HFpEF (n = 33,304, 5.2%) | HFrEF (n = 26,176, 4.1%) | No HF (n = 580,249, 90.7%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||

| ≤65 | 1,421 (4.3) | 1,872 (7.2) | 79,751 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| 66-70 | 5,228 (15.7) | 4,595 (17.6) | 174,393 (30.1) | |

| 71-75 | 6,295 (18.9) | 5,180 (19.8) | 135,525 (23.4) | |

| 76-80 | 6,628 (19.9) | 5,436 (20.8) | 91,761 (15.8) | |

| >80 | 13,732 (41.2) | 9,093 (34.7) | 98,819 (17.0) | |

| Age, y | 78.1 ± 8.5 | 76.5 ± 8.9 | 71.7 ± 10.0 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 21,580 (64.8) | 11,513 (44.0) | 352,827 (60.8) | <0.001 |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 1,234 (3.7) | 967 (3.7) | 20,338 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 2,487 (7.5) | 1,992 (7.6) | 41,811 (7.2) | |

| Urban-metro adjacent | 4,271 (12.8) | 3,599 (13.7) | 68,099 (11.7) | |

| Metro | 25,312 (76.0) | 19,618 (74.9) | 450,001 (77.6) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 32,406 (97.3) | 25,084 (95.8) | 541,433 (93.3) | <0.001 |

| Black | 525 (1.6) | 705 (2.7) | 18,606 (3.2) | |

| Other | 373 (1.1) | 387 (1.5) | 20,210 (3.5) | |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 8,964 (26.9) | 6,478 (24.7) | 135,238 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Northeast | 4,857 (14.6) | 3,329 (12.7) | 74,536 (12.8) | |

| South | 16,312 (49.0) | 13,552 (51.8) | 298,134 (51.4) | |

| West | 3,160 (9.5) | 2,806 (10.7) | 71,823 (12.4) | |

| Other | 11 (0.03) | 11 (0) | 518 (0.09) | |

| Utilization before index date | ||||

| CV-related ED visits | 6,380 (19.2) | 5,532 (21.1) | 12,924 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| CV-related inpatient visits | 5,681 (17.1) | 5,225 (20.0) | 10,708 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| CV-related inpatient stays >5 days | 1,663 (5.0) | 1,654 (6.3) | 1,797 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| CV-related outpatient visits | 18,167 (54.5) | 17,733 (67.7) | 96,627 (16.7) | <0.001 |

| Non-CV related ED visits | 10,824 (32.5) | 7,858 (30.0) | 87,659 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| Non-CV related inpatient visits | 8,536 (25.6) | 6,581 (25.1) | 47,471 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Non-CV related outpatient visits | 32,432 (97.4) | 25,222 (96.4) | 546,082 (94.1) | <0.001 |

| Drug history before index date | ||||

| Drugs known to cause TdPa | 15,053 (45.2) | 11,285 (43.1) | 170,607 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| Using >1 known TdP drug during same perioda | 6,591 (19.8) | 5,090 (19.4) | 59,723 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Using drugs with a possible risk of TdPa | 12,791 (38.4) | 9,203 (35.2) | 163,758 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Using drugs with a conditional risk of TdPa | 17,386 (52.2) | 12,115 (46.3) | 225,668 (38.9) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 12,035 (36.1) | 6,616 (25.3) | 122,716 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics | 13,132 (39.4) | 11,299 (43.2) | 33,035 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 7,436 (22.3) | 4,287 (16.4) | 121,825 (21.0) | 0.176 |

| Beta-blockers | 19,089 (57.3) | 17,450 (66.7) | 164,807 (28.4) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 11,059 (33.2) | 10,831 (41.4) | 153,587 (26.5) | <0.001 |

| Angiotensin-receptor blockers | 8,461 (25.4) | 6,003 (22.9) | 101,394 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| Digoxin | 2,152 (6.5) | 3,232 (12.3) | 5,895 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonists | 2,201 (6.6) | 3,341 (12.8) | 7,469 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiac arrhythmiab | 25,712 (77.2) | 22,263 (85.1) | 169,381 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 32,682 (98.1) | 25,613 (97.8) | 465,717 (80.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 17,941 (53.9) | 14,620 (55.9) | 194,153 (33.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16,845 (50.6) | 13,560 (51.8) | 85,681 (14.8) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 23,017 (69.1) | 21,960 (83.9) | 149,684 (25.8) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 8,818 (26.5) | 11,694 (44.7) | 31,613 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 29,288 (87.9) | 23,479 (89.7) | 432,773 (74.6) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 8,978 (27.0) | 6,681 (25.5) | 60,540 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 18,343 (55.1) | 13,710 (52.4) | 136,061 (23.4) | <0.001 |

Values are n (%).

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV = cardiovascular; ED = emergency department; HF = heart failure; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; TdP = Torsades de pointes.

From the QT drugs list at www.crediblemeds.org.

For the outcome of ventricular tachycardia, the percentage of cardiac arrhythmia in HFpEF, HFrEF, and no HF were 69.8%, 78.8%, and 22.2%, respectively, due to different ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for identifying cardiac arrhythmia (Supplemental Table 2).

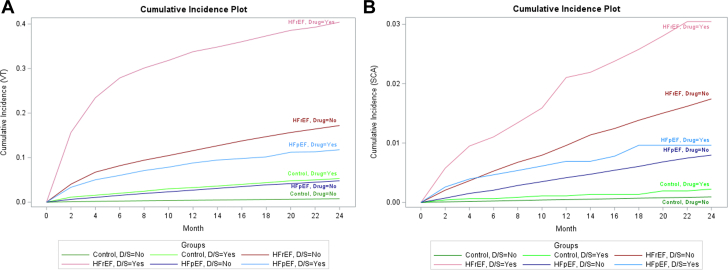

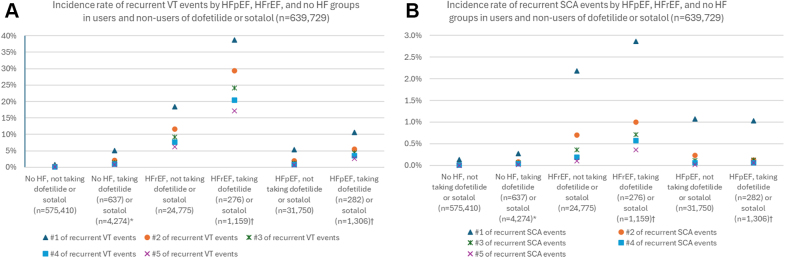

Incidence OF VT and SCA

The unadjusted cumulative incidence of VT was higher in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF than in those with no HF. Figure 2 shows the cumulative incident plot of VT and SCA. Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 3 show the number of recurrent VT events during observation periods. The unadjusted incidence rate of VT was higher in patients with HFpEF taking dofetilide or sotalol than in those with HFpEF not using dofetilide or sotalol (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 3). Figure 3B and Supplemental Table 4 show the number of recurrent SCA events over the observation periods. The unadjusted incidence rate of recurrent SCA was similar in patients with HFpEF taking dofetilide or sotalol and in patients with HFpEF not taking dofetilide or sotalol (Figure 3B, Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 2.

The Cumulative Incident Plot of Ventricular Tachycardia and Sudden Cardiac Arrest

(A) Ventricular tachycardia; (B) sudden cardiac arrest. D/S = Yes (represents patients using dofetilide or sotalol at least once); HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; Control = no heart failure; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Recurrent Ventricular Tachycardia and Sudden Cardiac Arrest Events by HFpEF, HFrEF, and No HF Groups in Users and Nonusers of Dofetilide or Sotalol (N = 639,729)

(A) Ventricular tachycardia; (B) sudden cardiac arrest. A total of 72 Patients were taking dofetilide and switched to sotalol, or vice versa; 34 patients were taking dofetilide and switched to sotalol, or vice versa. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Multinomial propensity score model

Supplemental Tables 5 and 6 show odds ratio estimates for generating propensity scores for HFpEF and HFrEF for the VT and SCA models, respectively. Supplemental Tables 7 and 8 present SMDs between HFpEF, HFrEF, and patients without HF before and after propensity score matching. Variables for which SMDs remained at ≥0.1 after propensity score matching were incorporated into a generalized Cox proportional model. Patients with HFpEF and HFrEF tended to have similar propensity scores. After matching, patients with HFpEF, HFrEF, and those patients without HF have similar SMDs, indicating that the covariates have achieved balance.

Generalized Cox proportional regression analysis

The adjusted HR for VT and SCA in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF was elevated compared to patients with no HF 1.99 (95% CI: 1.70-2.32) and 2.53 (95% CI: 1.98-3.23), 7.00 (95% CI: 6.10-8.02), and 5.19 (95% CI: 4.10-6.57), respectively, Table 2 and Central Illustration. In the overall population, the risk of VT associated with dofetilide or sotalol was increased compared to that in patients who did not use dofetilide or sotalol, but the risk of SCA was not (HR: 2.47 [95% CI: 1.89-3.23] and 1.39 [95% CI: 0.70-2.76], respectively, Table 2, Central Illustration). Use of dofetilide or sotalol increased the risk of VT in patients with HFrEF (HR: 1.53 [95% CI: 1.07-2.20]) and in those with HFpEF (HR: 2.34 [95% CI: 1.11-4.95]) but did not increase the risk of SCA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted HRs for Ventricular Tachycardia and Sudden Cardiac Arrest

| Group | Comparison | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 7.00 (6.10-8.02) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 1.99 (1.70-2.32) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 2.47 (1.89-3.23) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 1.53 (1.07-2.20) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 2.34 (1.11-4.95) |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 5.19 (4.10-6.57) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 2.53 (1.98-3.23) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 1.39 (0.70-2.76) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 1.82 (0.60-5.52) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 0.86 (0.33-2.24) |

D = dofetilide; S = sotalol; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

The multinomial propensity scoremethod was used to select potential covariates (listed in Supplemental Tables 7 and 8), and any characteristics with SMDs larger than 0.1 (listed in Supplemental Tables 7 and 8) were incorporated into the final model for double adjustment. The inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to stabilize the covariates-induced differences and survival analysis for the recurrent events model was performed. HFrEF, HFpEF, and taking D or S are the main effects, and HFrEF taking D or S and HFpEF taking D or S are the interaction terms in the model.

Central Illustration.

Arrhythmias in Patients With Heart Failure Prescribed Dofetilide or Sotalol

Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Sensitivity analyses

Intent-to-treat analytical approach

The adjusted HR for VT and SCA in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF was elevated compared to patients with no HF (1.98 [95% CI: 1.69-2.34] and 2.54 [1.99-3.25], 7.01 [95% CI: 6.11-8.04], and 5.13 [95% CI: 4.05-6.50], respectively) (Table 3). The risk of VT associated with dofetilide or sotalol was increased across the overall population, but not SCA (HR: 2.51 [95% CI: 1.96-3.21] and 1.24 [95% CI: 0.64-2.40], respectively) (Table 3). In patients with HFrEF, the risk of VT and SCA associated with dofetilide or sotalol did not reach significance (Table 3). Use of dofetilide or sotalol increased the risk of VT in those with HFpEF (HR: 2.11 [95% CI: 1.08-4.12] Table 3), but not SCA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted HRs for Ventricular Tachycardia and Sudden Cardiac Arrest, Using an Intent-to-Treat Analytical Approach

| Group | Comparison | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 7.01 (6.11-8.04) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 1.98 (1.69-2.34) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 2.51 (1.96-3.21) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 1.35 (0.96-1.90) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 2.11 (1.08-4.12) |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 5.13 (4.05-6.50) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 2.54 (1.99-3.25) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 1.24 (0.64-2.40) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 2.06 (0.76-5.61) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 0.72 (0.28-1.82) |

The multinomial propensity score method was used to select potential covariates (listed in Supplemental Tables 7 and 8), and any characteristics with SMDs larger than 0.1 (listed in Supplemental Tables 7 and 8) were incorporated into the final model for double adjustment. The inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to stabilize the covariates-induced differences and survival analysis for the recurrent events model was performed. HFrEF, HFpEF, and taking D or S are the main effects, and HFrEF taking D or S and HFpEF taking D or S are the interaction terms in the model.

Cohorts restricted to beneficiaries with 2 years of data. Supplemental Figure 2 shows the flow diagram for selecting patients with 2 years of data from the individual index date. There were 3,082 dofetilide or sotalol and 63,665 non-dofetilide or sotalol users removed from the cohort. The total cohort was reduced from 639,729 to 572,982 individuals. The total number of subjects eligible for analysis was 27,207 patients with HFpEF (842 patients using dofetilide or sotalol at least once after index date), 20,820 patients with HFrEF (747 patients using dofetilide or sotalol at least once after index date), and 524,955 patients without HF (3,123 patients using dofetilide or sotalol at least once after index date.) The unadjusted incidence rate and recurrent of VT and SCA events remained similar to those in the primary analysis (Supplemental Figure 3, Supplemental Tables 9, and 10).

The adjusted HRs for VT and SCA were higher in patients with HFrEF compared to patients without HF (7.12 [95% CI: 6.18-8.20] and 5.40 [95% CI: 4.10-7.12], respectively) (Table 4). The risk of VT associated with dofetilide or sotalol was increased across the overall population but the risk of SCA was not elevated (HR: 2.50 [95% CI: 1.83-3.42] and 1.69 [95% CI: 0.78-3.65], respectively) (Table 4) in patients who used dofetilide or sotalol compared to those who did not. The risk of VT and SCA was not elevated significantly in patients with HFrEF using dofetilide or sotalol and in those with HFpEF using dofetilide or sotalol compared to patients with no HF (Table 4). Using intent-to-treat analytical approach yielded similar results as the on-treatment approach (Table 5).

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analysis: Adjusted HRs for Ventricular Tachycardia, Using an On-Treatment Approach, Among Patients Having 2 Years of Observations

| Group | Comparison | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 7.12 (6.18-8.20) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 1.98 (1.68-2.33) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 2.50 (1.83-3.42) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 1.55 (1.00-2.41) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 2.18 (0.93-5.12) |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 5.40 (4.10-7.12) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 2.34 (1.68-3.28) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 1.69 (0.78-3.65) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 2.04 (0.58-7.12) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 0.58 (0.15-2.27) |

The multinomial propensity score method was used to select potential covariates (listed in Supplemental Tables 11 and 12), and any characteristics with SMDs larger than 0.1 (listed in Supplemental Tables 11 and 12) were incorporated into the final model for double adjustment. The inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to stabilize the covariates-induced differences and survival analysis for the recurrent events model was performed. HFrEF, HFpEF, and taking D or S are the main effects, and HFrEF taking D or S and HFpEF taking D or S are the interaction terms in the model.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Analysis: Adjusted HRs for Ventricular Tachycardia, Using an Intent-to-Treat Approach, Among Patients Having 2 Years of Observations

| Group | Comparison | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 7.13 (6.18-8.22) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 1.98 (1.68-2.33) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 2.51 (1.88-3.36) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 1.39 (0.91-2.11) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 1.99 (0.91-4.36) |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 5.29 (4.01-6.98) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 2.35 (1.68-3.29) |

| Taking D or S | Taking D or S vs not taking D or S | 1.47 (0.68-3.22) |

| HFrEF taking D or S | HFrEF taking D or S vs HFrEF not taking D or S | 2.58 (0.81-8.18) |

| HFpEF taking D or S | HFpEF taking D or S vs HFpEF not taking D or S | 0.56 (0.15-2.14) |

The multinomial propensity score method was used to select potential covariates (listed in Supplemental Tables 11 and 12), and any characteristics with SMDs larger than 0.1 (listed in Supplemental Tables 11 and 12) were incorporated into the final model for double adjustment. The inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to stabilize the covariates-induced differences and survival analysis for the recurrent events model was performed. HFrEF, HFpEF, and taking D or S are the main effects, and HFrEF taking D or S and HFpEF taking D or S are the interaction terms in the model.

Subgroup analysis (only including patients using dofetilide or sotalol)

The subgroup analysis included patients using dofetilide or sotalol only, including 1,554 HFpEF patients, 1,401 HFrEF patients, and 4,839 patients without HF. The risk of VT and SCA associated with dofetilide/sotalol in patients with HFrEF was higher than in those without HF, and the risk of dofetilide/sotalol-associated VT and SCA in patients with HFpEF was higher than that in patients without HF (Table 6).

Table 6.

Subgroup Analysis: Adjusted HRs for Ventricular Tachycardia and Sudden Cardiac Arrest for Patients Using Dofetilide or Sotalol

| Group | Comparison | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 9.72 (7.12-13.28) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 3.53 (2.22-5.62) |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | ||

| HFrEF | HFrEF vs no HF | 11.22 (4.69-26.85) |

| HFpEF | HFpEF vs no HF | 2.63 (1.00-6.87) |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

The multinomial propensity score method was used to select potential covariates (listed in Supplemental Table 13), and any characteristics with SMDs larger than 0.1 (listed in Supplemental Table 13) were incorporated into the final model for double adjustment. The inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to stabilize the covariates-induced differences and survival analysis for the recurrent events model was performed.

Discussion

The risk of VT, but not SCA, is increased in patients with HFpEF prescribed dofetilide/sotalol. Our results confirm previous findings that the risk of drug-associated VT is increased in patients with HFrEF.

Increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias was reported in an experimental HFpEF model.22,23 In rats with salt-induced HFpEF, the arrhythmogenicity index was increased, and ventricular arrhythmias induced by programmed electrical stimulation occurred more frequently compared to controls.22 VT is significantly more prevalent in patients with HFpEF than in those without HF, and HFpEF was the only variable independently associated with an increased risk of VT.8

While these previous studies have reported an increase in overall risk of ventricular arrhythmias associated with HFpEF, whether patients with HFpEF are at increased risk of drug-induced arrhythmias has not been well-studied. We reported previously that patients with HFpEF demonstrate enhanced responsiveness to drug-induced QT interval lengthening,9 and the risk of QT prolongation associated with dofetilide and sotalol was increased significantly in patients with HFpEF compared to patients without HF.10 In the present study, the risk of VT associated with dofetilide and sotalol was higher in patients with HFpEF than in individuals without HF. However, this did not translate into an increased risk of drug-associated SCA. Mechanisms of increased risk of overall and drug-induced arrhythmias in patients with HFpEF include electrophysiologic and ion channel alterations that occur in patients with HFpEF, including downregulation of IKr, Ito, and IK122 and up-regulation of inward calcium22 and/or late sodium current,24 leading to increasing arrhythmia.8,22,23

Incidences of VT associated with dofetilide and sotalol in patients without HF in our study are comparable to those previously reported. In a retrospective cohort of 327 patients undergoing inpatient initiation of dofetilide or sotalol, 7% developed ventricular arrhythmias,25 slightly higher than the 5% incidence in our patients without HF. Boriani et al26 reported a 7.8% incidence of VT associated with dofetilide and sotalol during the 3- to 5-day initiation phase in patients with mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 40%. This is lower than the incidence of dofetilide/sotalol-associated VT that we report in this study. However, the Boriani study reported the incidence of VT during 3-5 days of inpatient dofetilide/sotalol initiation, while our analysis was longitudinal, and we reported the incidences of recurrent VT associated with these drugs over a much longer period of time, resulting in a higher incidence of dofetilide/sotalol-associated ventricular proarrhythmia.

Patients undergoing initiation of therapy or reloading with dofetilide or sotalol should be admitted for at least 3 days to an institution that can provide continuous electrocardiogram monitoring, to assess the QT interval and discharge patients on doses that are unlikely to result in proarrhythmia.5 However, there remains a risk of postdischarge QT prolongation and proarrhythmia associated with these drugs, particularly in patients with HF. Patients with HFrEF who continued dofetilide following inpatient initiation had a significantly higher 1-year mortality incidence than those who discontinued the drug during inpatient initiation.27 Among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the incidence of postdischarge QT prolongation associated with dofetilide and sotalol was 6% and 10%, respectively. Sotalol has been associated with an increased risk of mortality, presumably due to proarrhythmia.28 While we found that patients with HFpEF are at increased risk of dofetilide/sotalol-associated VT, this did not translate into an increased risk of SCA. In our population, fewer than 1% of those who developed VT experienced SCA.

Dofetilide and sotalol were investigated together in this study because both: 1) potently inhibit IKr and are high-risk drugs for QT prolongation and TdP; and 2) are guideline-recommended for the management of atrial fibrillation, which is a common comorbidity in patients with HFpEF.5 In the most recent American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/American College of Clinical Pharmacy/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation, both dofetilide (Class 2a) and sotalol (Class 2b) are recommended for maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with normal left ventricular function as well as in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction <40%.5 However, rather than to assess the effect of specific drugs, the purpose of this study was to determine whether patients with HFpEF are more susceptible to drug-induced arrhythmias than patients who do not have HF. Since dofetilide and sotalol are well-known to be proarrhythmic and used commonly in patients with HFpEF, these agents serve as good “probe” drugs to assess the risk of drug-induced proarrhythmia in this population.

In our sensitivity analyses, we mimicked the intent-to-treat method employed in prospective studies by carrying the first exposure of dofetilide or sotalol forward without considering discontinuation as censoring. We found similar results in the VT and SCA model compared to the main analysis, with a slightly decreased risk of drug-associated VT in the HFrEF and HFpEF groups associated with dofetilide and sotalol, suggesting that on-treatment dofetilide and sotalol may be the primary reason for drug-related VT. In the other sensitivity analysis, we restricted the population to patients who had at least 2 years of enrollment resulting in 3,082 patients (about 40% of the population of the main analysis) of dofetilide and sotalol users and 63,665 (about 10% of the population of the main analysis) non-dofetilide and non-sotalol users removed from the data sets. We observed similar results as the main analysis, although with a somewhat decreased risk of drug-associated VT that did not reach significance. The main reason may lie with the decreased sample size after removing the patients not enrolled in Medicare continuously for 2 years. Subgroup analysis among dofetilide and sotalol users shows HFpEF and HFrEF are significant predictors of VT and SCA, supporting the findings of previous studies that patients with HFpEF and HFrEF have an elevated risk of proarrhythmic events.

Our analysis has several strengths. The Medicare FFS data comprise large sample sizes, with large power to detect differences. While the effect of confounders is a concern in observational studies, we included steps to minimize the effect of covariates and adjusted possible repeated occurrences of VT/SCA in individual patients. We selected patients who may have similar cardiovascular conditions when taking dofetilide or sotalol, given that VT/SCA events may be moderated by patients' characteristics. As a result, we frequency-matched the study population based on the characteristics of dofetilide or sotalol users. In addition, we balanced the prevalence of recorded cardiovascular effects and other pre-existing conditions (demographics, utilization, and drug history) by propensity score matching the HFpEF and HFrEF groups and the patients without HF. After matching, we further adjusted repetitive measures using a generalized Cox proportional model capturing the longitudinal effect of HF while controlling for confounders, enabling a comprehensive understanding of disease progression, given that in our analysis, SCA and VT are not terminal events.

Limitations of this analysis warrant consideration. This data set comprises nonrandomized patients, so there is a possibility of unmeasured confounding; in particular, patients without access to a medication synchronization program were not included. The data set does not include death records, so we may underestimate the effect of dofetilide/sotalol-associated SCA and VT-associated death and were not able to investigate competing risks with death. However, we selected patients who were Medicare enrolled for at least 1 year during our observation period to minimize this effect. Diagnoses of HFpEF and HFrEF are dependent on ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes. Information regarding dofetilide or sotalol doses was not available. We used ICD-9 and ICD 10 to define VT, but we have no information on duration or morphology. The majority of Medicare patients are over 65 years old, so our findings may not be applicable to younger patients with HFpEF or HFrEF. Electrocardiograms are not available in the Medicare data set, so we had no information regarding QT intervals. Our data set predates the recommendation for use of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors for both HFrEF and HFpEF.29 Laboratory values were not available to include in the propensity score, so the possibility of confounding induced by residuals cannot be excluded. Finally, we did not stratify the generalized Cox proportional model according to a stratified risk score for VT/SCA because of the complexity of repeated events that warrant another study to address (eg, the risk factors for the 1st and 2nd VT/SCA event may not be the same) and the issue of sample size (numbers of patients who have 2nd or 3rd events diminish).

Conclusions

The risk of VT in patients prescribed dofetilide or sotalol was higher in those with HFpEF as well as in those with HFrEF compared to patients without HF. However, there was no elevated risk of drug-associated SCA in patients with HFpEF.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Patients with HFpEF are at increased risk of VT, but not SCA, associated with dofetilide and sotalol.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE: Clinicians should be particularly attentive to risk factors for QT interval prolongation and proarrhythmia in patients with HFpEF who are receiving dofetilide or sotalol for management of atrial fibrillation and enhanced QT interval monitoring may be warranted in this population.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK 1: Further study is needed to determine the risk of drug-induced proarrhythmia with other QT interval-prolonging drugs in patients with HFpEF.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK 2: While experimental models have documented some specific cardiac ion channel changes that occur during the development of HFpEF, further study is needed to assess the specific mechanisms by which patients with HFpEF may be at increased risk of drug-induced proarrhythmia.

Funding support and author disclosures

Funded in part, with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded, in part by Grant Number UL1TR002529 from the NIH, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. This project was also supported in part by the NHLBI (R01HL153114). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Tisdale J.E., Chung M.K., Campbell K.B., et al. Drug-induced arrhythmias: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;142:e214–e233. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tisdale J.E., Overholser B.R., Wroblewski H.A., et al. Enhanced sensitivity to drug-induced QT interval lengthening in patients with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:1296–1305. doi: 10.1177/0091270011416939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hindricks G., Potpara T., Dagres N., et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joglar J.A., Chung M.K., Armbruster A.L., et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:109–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redfield M.M., Borlaug B.A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. A review. JAMA. 2024;329:827–838. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox J.E., Rosenberg J., Vallakati A., Gheorghiade M., Shah S.J. Usefulness of electrocardiographic QT interval to predict left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1760–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pezawas T., Burger A.L., Binder T., Diedrich A. Importance of diastolic function for the prediction of arrhythmic death: a prospective, observer-blinded, long-term study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho J.H., Leong D., Cuk N., et al. Delayed repolarization and ventricular tachycardia in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tisdale J.E., Jaynes H.A., Overholser B.R., et al. Enhanced response to drug-induced QT interval lengthening in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Card Fail. 2020;26:781–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C.-Y., Overholser B.R., Sowinski K.M., Jaynes H.A., Kovacs R., Tisdale J.E. Drug-induced QT interval prolongation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. PLoS One. 2024;19(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0308999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S., Zoble R.G., Yellen L., et al. Efficacy and safety of oral dofetilide in converting to and maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: the symptomatic atrial fibrillation investigative research on dofetilide (SAFIRE-D) study. Circulation. 2000;102:2385–2390. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarlagadda B., Vuddanda V., Dar T., et al. Safety and efficacy of inpatient initiation of dofetilide versus sotalol for atrial fibrillation. J Atr Fibrillation. 2017;10:1805. doi: 10.4022/jafib.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason J. A comparison of seven antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Electrophysiologic Study versus Electrocardiographic Monitoring Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:452–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh B.N., Kehoe R., Woosley R.L., Scheinman M., Quart B. Multicenter trial of sotalol compared with procainamide in the suppression of inducible ventricular tachycardia: a double-blind, randomized parallel evaluation. Am Heart J. 1995;129:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torp-Pedersen C., Moller M., Bloch-Thomsen P.E., et al. Dofetilide in patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:857–865. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909163411201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann M.H., Hardy S., Archibald D., Quart B., MacNeil D.J. Sex difference in risk of torsade de pointes with d, l-sotalol. Circulation. 1996;94:2535–2541. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Br Med J. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woosley R.L., Heise C.W., Gallo T., Woosley R.D., Lambson J., Romero K.A. QTdrugs List. www.CredibleMeds.org AZCERT, 1457 E. Desert Garden Dr, Tucson, AZ 85718.

- 19.Braga J.R., Tu J.V., Austin P.C., Sutradhar R., Ross H.J., Lee D.S. Recurrent events analysis for examination of hospitalizations in heart failure: insights from the Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT) trial. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2018;4:18–26. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcx015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum P.R., Rubin D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen T.-L., Collins G.S., Spence J., et al. Double-adjustment in propensity score matching analysis: choosing a threshold for considering residual imbalance. BMC Medical Res Methodol. 2017;17:78. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho J.H., Zhang R., Kilfoil P.J., et al. Delayed repolarization underlies ventricular arrhythmias in rats with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2017;136:2037–2050. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho J.H., Zhang R., Aynaszyan S., et al. Ventricular arrhythmias underlie sudden death in rats with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pourrier M., Williams S., McAfee D., Belardinelli L., Fedida D. Crosstalk proposal: the late sodium current is an important player in the development of diastolic heart failure (heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction) J Physiol. 2014;592:411–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.262261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agusala K., Oesterle A., Kulkarni C., Caprio T., Subacius H., Passman R. Risk prediction for adverse events during initiation of sotalol and dofetilide for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38:490–498. doi: 10.1111/pace.12586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boriani G., Lubinski A., Capucci A., et al. A multicentre, double-blind randomized crossover comparative study on the efficacy and safety of dofetilide versus sotalol in patients with inducible sustained ventricular tachycardia and ischaemic heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:2180–2191. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham J.M., Saliba W.I., Vekstein C., et al. Safety of oral dofetilide for rhythm control of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:772–776. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valembois L., Audureau E., Takeda A., Jarzebowski W., Belmin J., Lafuente-Lafuente C. Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005049.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heidenreich P.A., Bozkurt B., Aguilar D., et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:e263–e421. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.