Abstract

ETV2 is an essential transcription factor as Etv2 null murine embryos lack all vasculature, blood and are lethal early during embryogenesis. Previous studies have established that ETV2 functions as a pioneer factor and directly reprograms fibroblasts to endothelial cells. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms regulating this reprogramming process remain incompletely defined. In the present study, we examined the ETV2-RIG1 cascade as regulators that govern ETV2-mediated reprogramming. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) harboring an inducible ETV2 expression system were used to overexpress ETV2 and reprogram these somatic cells to the endothelial lineage. Single-cell RNA-seq from reprogrammed fibroblasts defined the induction of the transcriptional network involved in Rig1-like receptor signaling pathways. Studies using ChIP-seq, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and transcriptional assays demonstrated that ETV2 was a direct upstream activator of Rig1 gene expression. We further demonstrated that the knockdown of Rig1 and separately, Nfκb1 using shRNA significantly reduced the efficiency of endothelial cell reprogramming. These results highlight that ETV2 reprograms fibroblasts to endothelial cells by directly activating RIG1. These findings extend our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying ETV2-mediated reprogramming and will be important in the design of revascularization strategies for the treatment of ischemic tissues such as ischemic heart disease.

Keywords: ETV2, RIG1, Reprogramming

Subject terms: Reprogramming, Angiogenesis

Introduction

Direct cellular reprogramming holds tremendous promise as a regenerative therapy for restoration of damaged tissues and organs. This process is governed by master regulators or pioneer transcription factors (TFs), orchestrating the conversion of a somatic cell lineage into another lineage. These pioneer TFs modulate the epigenetic landscape through euchromatin/heterochromatin formation to initiate the networks of gene expression and signaling cascades1. We and others have shown that ETV2 is one of the pioneer TFs that governs the direct reprogramming of somatic cells into endothelial lineage cells2–4. Furthermore, these studies have also demonstrated the therapeutic potential in treating ischemia, although the application was limited to ex vivo reprogramming followed by cell transplantation. Despite its ability to reprogram and generate endothelial cells, the underlying mechanism behind ETV2-mediated reprogramming is incompletely defined.

The current attempts to define the mechanistic basis of pioneer TF-guided reprogramming focus largely on the modulation of epigenetic features. Owing to the uniqueness of each cell type, each pioneer TF adopts its unique method to remodel the epigenetic landscape. For example, some pioneer TFs (e.g. ASCL1) bind to target genes of both the closed and open chromatin with high specificity (canonical binding motifs), whereas other pioneer TFs (e.g. OCT4, SOX2) bind to both canonical and non-canonical binding motifs1,5,6. There are also variations regarding whether a TF affects the histone modification status and/or DNA methylation as well as whether it recruits other TFs or cofactors1. Our lab has recently pursued a single cell analysis in combination with other genomic analyses (MNase-seq, NOMe-seq, ATAC-seq, etc.) to decipher the role of ETV2 as a pioneer factor and examine ETV2-mediated direct reprogramming of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to the endothelial lineage. These studies demonstrated that ETV2 recruits the chromatin modifying ATPase, BRG1, to remodel the chromatin status of ETV2 downstream genes such as Flt1, Lmo2 and Tcf127–9. However, the complex process of changing the somatic cell identity, may not be solely attributable to a single mechanistic process of ETV2-BRG1-mediated euchromatin formation of endothelial-lineage genes. This is clearly evident in other reprogramming studies that demonstrate the role of RIG1 and TLR3 inflammatory pathway activation in iPSC (OCT3/4/SOX2/KLF4) production10,11, the involvement of ZFP281-mediated suppression of inflammatory response in enhancing cardiac reprogramming12, or the role of metabolic switching in neuronal reprogramming13. Collectively, these reprogramming studies emphasize the importance of multiple mechanisms that govern the reprogramming process including the inflammatory signaling networks.

In the present study, we mined our single cell databases during endothelial reprogramming and identified a significant enrichment of innate immune responses following ETV2 mediated reprogramming to the endothelial lineage. We hypothesized that ETV2 directly or indirectly regulated the innate immune response and reprogramming. We used ETV2 ChIP-seq, electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and transcriptional assays to demonstrate that ETV2 was a direct upstream regulator of the Rig1 gene. We then demonstrated that shRNA mediated knockdown of Rig1 transcript expression significantly decreased ETV2 mediated reprogramming to the endothelial lineage. These studies further examine and define the mechanisms whereby pioneer factors such as ETV2 mediate lineage specific reprogramming.

Materials and methods

Mouse ES cell lines

MEFs with inducible Tet-on, HA-tagged ETV2 expression system (iHA-ETV2 MEFs) were isolated from E14.5 embryos from the iHA-ETV2 transgenic mouse model as previously described8,14. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1× penicillin/streptomycin and 1× nonessential amino acids at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cells were positively sorted for THY1.2-APC (1:200, BioLegend, Cat. No. 105312) expression and negatively sorted for CD31 (1:200, BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 553373), CD41 (1:200, BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 558040), CD45 (1:200, eBioscience, Cat. No. 12-0451-82), CD144 (1:200, eBioscience, Cat. No. 12-1441-82), CD202b (1:200, BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 560052) and CD309 (1:200, eBioscience, Cat. No. 12-5821-82) expression, all in the PE channel (Supplementary Table 1).

Knockdown of Rig1 and Nfκb1 and MEF reprogramming

Lentiviral particles for gene knockdown with shRNA were made as previously described15,16. MEFs were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells per well in a six well plate. Rig1 and NFκB shRNA constructs were obtained from the University of Minnesota Genomics Center. Each of the shRNA lentiviruses were generated by transfecting HEK293T cells seeded on 15 cm cell culture dishes with the transfer vector (including the respective shRNA), dR8.2 packaging vector, and VSV.G envelope vector using Fugene HD transfection reagent (Promega). iHA-ETV2 MEFs were infected with the respective lentiviral constructs when seeding the cells and 24 h after the initial seeding using the Lentiblast Premium reagent (OZBiosciences, 1:1000). Doxycycline was added at 1 μg/ml 48 h post-2nd transduction. MEFs were cultured using the same media and conditions as with isolation process. Cells were harvested for flow cytometry analysis 24 h following doxycycline administration.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described17,18. MEFs were collected and stained as previously described using a FACS Aria (BD) machine18. FLK1-PE antibody (1:200, eBioscience, Cat. No. 12-5821-82) was used to quantify FLK1+ endothelial progenitor cells. Propidium iodide (1:1000, eBioscience, Cat. No. 1423090) was used as a viability dye. Briefly, cells were detached and dissociated using trypsin (0.25%, Gibco, Cat. No. 25200072). Trypsin was neutralized using the cell culture media described above. Cells were washed with FACS buffer (20% cell culture media, 80% PBS) and stained with the FLK1 antibody at the dilution described above for 30 min. Following a 30-min incubation period, the cells were diluted and washed twice with FACS buffer, then resuspended in 200 μl PI solution. All centrifugations were performed at 400×g for 4 min. The gating strategy is outlined in Supplementary Fig. 1.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was performed as previously described19. Briefly, MEFs were harvested as described in the flow cytometry analysis procedure (see above). RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 74104) was used to isolate total RNA from harvested cells. MEFs were lysed in RLT lysis buffer, then a gDNA column was used to eliminate genomic DNA. RNeasy column was then used to eliminate contaminants and elute RNA. SuperScript IV VILO kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 11756050) was used to synthesize complementary DNA from isolated RNA. RT-qPCR was performed using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 4444557) and TaqMan probes (Supplementary Table 2).

scRNA-Seq, ETV2 ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq data analysis

The processed Seurat object was derived from previous publications from our laboratory7. 3,539, and 7,202 high-quality single cells from 24 h, and 7 days post-induction of ETV2 in MEFs, as well as 948 undifferentiated MEFs were retrieved from the data set. Manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) were used for visualizing the scRNA-seq results. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using the fgseaMultilevel function from the fgsea package (v1.24.0). We focused on Gene Ontology (GO) terms under the Defense Response category (GO:0006952). A one-sided enrichment test was used to evaluate significance, with p-value adjustment performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. The statistical cutoff was set at p-value < 0.05, and we chose the top 11 GO terms to present in the figure.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed as described previously19,20. Briefly, TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega, Cat. No. L1170) was used to translate HA-tagged ETV2 in vitro (Western blot of the HA-ETV2 protein is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2). Protein identity was confirmed using western blot analysis. The ETV2 consensus binding site was identified within 1000 base pairs from the Rig1 transcription start site. The identified binding site was synthesized through integrated DNA Technologies with and without IR700 modification on the 5′ end, as well as AGG to TTC mutation in the ETV2 consensus binding site. Synthesized oligonucleotides are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Complimentary strands were annealed to generate labeled probes, unlabeled competitor, and unlabeled mutants by placing oligonucleotides in boiling water for 10 min and cooling them down overnight at room temperature. 5 nM unlabeled competitor, mutants, and HA antibody (1:3 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. C29F4) were allowed to prebind to 1 μl of in vitro synthesized HA-tagged ETV2 for 10 min at room temperature with binding buffer, poly dI-dC and poly-L Lysine. 0.1 nM labeled probe was added after prebinding reaction and the reaction was incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Protein-DNA complexes were loaded on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE (40 mmol/L Tris pH 8.3, 45 mmol/L boric acid, and 1 mmol/L EDTA) and electrophoresis was performed at 70 V for ~ 80 to 100 min. Fluorescence was detected using an Odyssey CLx imager (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed as previously described21,22. Briefly, 1 μl of translated protein from a 50 μl reaction was denatured and reduced using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 95 °C for 5 min. Denatured protein was loaded in a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. The electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 1 h and 30 min. Protein was then transferred to 0.2 µm polyvinyldene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Cat. No. 1704156) at 2.5 A, 25 V for 7 min. The PVDF membrane was then blocked with 10% (w/v) milk and incubated with primary and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Supplementary Table 2), overnight at 4 °C and 2 h at room temperature, respectively.

Dual reporter firefly luciferase assay (transcriptional assay)

Firefly luciferase assay was performed as described previously19,23. Briefly, a 600 base pair promoter including the ETV2 binding motif from the Rig1 promoter was PCR amplified and cloned into the pGL3 vector to generate the pGL3-Rig1-Luc plasmid construct. HEK293T cells were seeded at 50,000 cells per well in a 24-well plate. 24 h upon seeding, cells were transfected with the generated construct, renilla luciferase expressing vector (pRL-null), increasing concentrations of ETV2 expression plasmid and reciprocal amount of empty expression plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000001) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were harvested 36 h after transfection to quantify luciferase activities using Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega, E1910) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were washed and lysed in 100 μl PLB buffer/well for 15 min, at room temperature by gently shaking the plate at 60 rpm. 20 μl of the lysate was plated into a 96 well dish. Each well was dispensed with 100 μl LAR II, shaken for 2 s, then firefly luciferase activity was measured over 8 s read time. Then 100 μl of Stop&Glo buffer was dispensed to the same well, shaken for 2 s and renilla luciferase activity was measured. Renilla luciferase activity was used to normalize the firefly luciferase activity.

Statistical analysis

All experiments are repeated at least three times, and the reported values are mean ± S.E.M. To determine the statistical significance of the data, Student’s t-test was used for comparing one independent variable between two groups, one-way ANOVA for comparing one independent variable across multiple groups and two-way ANOVA for comparing two-independent variables for across multiple groups. *p-value ≤ 0.05, **p-value ≤ 0.01, ***p-value ≤ 0.001, ****p-value ≤ 0.0001.

Results

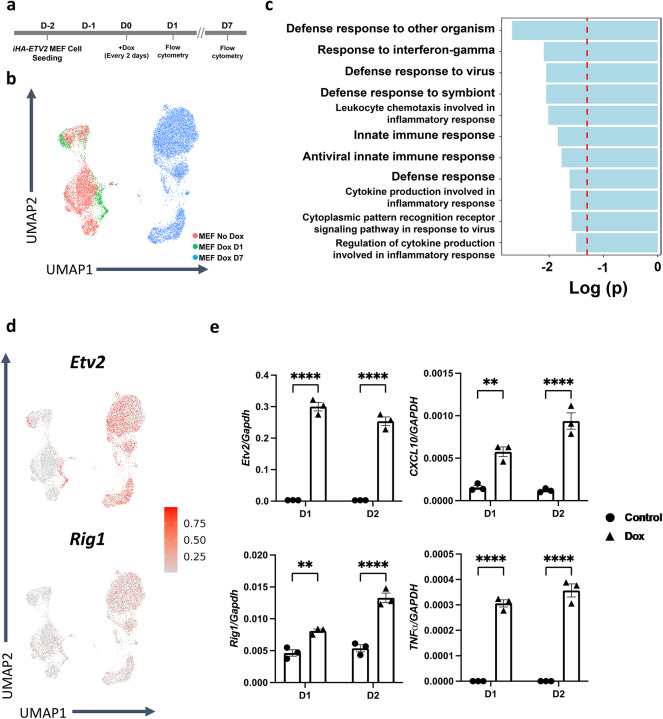

RIG1 is upregulated in reprogrammed endothelial cells

scRNA-seq dataset was obtained from reprogrammed E13.5 iHA-ETV2 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that were reprogrammed to the endothelial lineage by overexpressing ETV2 under the control of the doxycycline (dox) responsive element as previously described7. iHA-Etv2 MEFs were seeded two days prior to doxycycline administration, and doxycycline was administered every two days (Fig. 1a). Control iHA-Etv2 MEFs (no dox, day 7) and MEFs 24 h and 7 days post-ETV2 overexpression were analyzed from this dataset. Cells were clustered and plotted onto UMAP as shown in Fig. 1b. ETV2 expression level was increased upon doxycycline induction, leading to a robust expression of endothelial cell markers including: Flk1, Lmo2, Cdh5, and Smoc2 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Differential expression analysis and gene set enrichment analysis revealed numerous genes and pathways that were altered in ETV2 overexpressing cells, including upregulation of stress response pathways in reprogrammed cells (Fig. 1c). Three terms from the stress response pathways (defense response to virus, innate immune response, antiviral innate immune response) involved RIG1. The projection of Rig1 expression level onto the UMAP demonstrated that its RNA expression level followed the same trend as the Etv2 expression pattern, with Etv2 overexpressed cells showing higher Rig1 expression (Fig. 1d). The relative expression levels of Rig1 were experimentally quantified in reprogrammed fibroblasts at 24 and 48 h post-Etv2 overexpression, which verified the increase in Rig1 expression that was observed computationally. Proinflammatory cytokines, CXCL10 and TNF-α, which are downstream targets of the RIG1-like receptor (RLR) pathway, were also upregulated at both time points following ETV2 overexpression (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Upregulation of stress response transcripts in fibroblasts undergoing reprograming. (a) Timeline of ETV2 overexpression in MEFs with doxycycline administration (1 μg/ml). (b) UMAP of scRNA-seq for uninduced iHA-ETV2 MEFs (948 cells), 24 h (3539 cells) and 7 days (7202 cells) post-doxycycline induction (i.e. ETV2 overexpression). (c) GO terms upregulated in D1 reprogrammed MEFs compared to the wildtype. (d) Transcriptional expression level of Etv2 (left) and Rig1 (right) projected on top of the UMAP plot. (e) Relative transcriptional expression level of Etv2, Rig1, Cxcl10 and TNF-α in iHA-ETV2 MEFs at day 1 (D1) and at day 2 (D2) post-doxycycline administration to drive ETV2 overexpression (n = 3 biological replicates; two-way ANOVA; **p < 1.0 × 10−2, ****p < 1.0 × 10−4).

In order to further examine the impact of the response of Rig1 expression to ETV2 mediated endothelial cell reprogramming, transcriptional expression levels of RLR pathway proteins were analyzed24–26. Compared to Control MEFs, D7 reprogrammed MEFs demonstrated significantly higher expression level of RLR pathway gene transcripts such as Mavs, Ikk-α, β, γ, NF-κB1 and Rela (Fig. 2). Altogether, the overall upregulation of Rig1 and RLR pathway genes following ETV2 overexpression suggested the notion that Rig1 was an ETV2 downstream target.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional expression level of Rig1, and RLR pathway transcripts are upregulated in ETV2 overexpressed MEFs. Data are obtained from the single cell analyses of ETV2 mediated reprogramming of MEFs to the endothelial lineage. MEF indicates iHA-ETV2 MEFs without doxycycline administration and ETV2-OE indicates ETV2-overexpressed iHA-ETV2 MEFs seven days post-doxycycline administration. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. in log scale (Two-tailed unpaired t-test; **p < 1.0 × 10−2, ****p < 1.0 × 10−4).

ETV2 binds and transcriptionally activates Rig1 gene expression

Previous studies have demonstrated that RIG1 and the RLR pathway were activated during cellular reprogramming following the introduction of a foreign RNA being introduced to the cell(s) using a retroviral vector11. Our iHA-ETV2 MEF reprogramming strategy utilizes a Tet-on expression system, which does not involve foreign RNA. To this end, we first verified that Rig1 expression was not upregulated in MEFs from the wildtype CD1 mouse following doxycycline administration. RT-qPCR was used to measure relative Rig1 expression levels in wild-type MEF cells with and without doxycycline administration at different time points. We observed no difference in the Rig1 transcript expression level between treated (Dox) and untreated (no Dox) cells (Supplementary Fig. 4).

This result demonstrated that the exposure to Dox alone did not induce Rig1 transcript expression. Therefore, we examined the hypothesis that ETV2 was a direct upstream regulator of Rig1 gene expression. ETV2 ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data from day 1 reprogrammed MEFs demonstrated that ETV2 binds to the Rig1 promoter and an intergenic peak within the intron 1 (Fig. 3a). We further evaluated the ETV2 binding site in the promoter region as this region is directly involved in transcription initiation and has a direct effect on gene expression. Within the Rig1 promoter, two adjacent, potential ETV2 binding sites were identified based on the consensus sequence (AGGAA)27–29. EMSA was then performed to determine whether ETV2 binds to these sites in vitro. Since two binding motifs were adjacent (four base pairs away) from each other, three unlabeled mutant oligos were used to identify whether ETV2 could bind to these two adjacent motifs. Mutant #1 had an AGG to TTC mutation for binding site 1 (Fig. 3b, top), mutant 2 had the same mutation for binding site #2, and mutant #3 had the same mutation on both binding sites. As shown in Fig. 3c, protein-DNA bands were observed in the lanes with ETV2 protein (translated in vitro and verified through Western blotting, Fig. S3) and labeled oligonucleotides, as well as with mutants #2 and #3. This indicates that the unlabeled mutant oligonucleotides still retained their ability to bind ETV2 as long as site 2 (Fig. 3c, Top) was preserved. Further controls included super shift (of the protein-DNA complex) and heat denaturation of the antibody used for the super shift of the complex. Collectively, these EMSA results demonstrate that ETV2 binds to Site #2 in the Rig1 promoter.

Fig. 3.

ETV2 binds and transcriptionally activates Rig1 gene expression. (a) ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq coverage map projected on to the UCSC genome browser. Red box indicates ~ 800 bp region upstream of Rig1 gene. (b) Schematic of two adjacent ETV2 binding motifs in the Rig1 promoter site (top). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing ETV2 binding to identified motifs. Infrared dye-labeled oligonucleotides with two ETV2 binding motifs were annealed (Lane 1) and incubated with HA-tagged ETV2 protein synthesized in vitro (Lane2), with unlabeled oligonucleotides (Lane 3), with unlabeled oligonucleotides with mutation of the binding motif 1 (Lane 4), with unlabeled oligonucleotides with mutation of the binding motif 2 (Lane 5), with unlabeled oligonucleotides with mutations of both binding motifs (Lane 6), with HA antibody (Lane 7), and with heat inactivation of the HA antibody (Lane 8) (bottom). (c) Schematic of firefly luciferase construct driven by the Rig1 promoter which harbors the ETV2 binding site (left). Dual luciferase reporter assay showing dose-dependent increase of firefly luciferase activity upon addition of increased HA-ETV2 plasmids. Luciferase activity was normalized with the renilla luciferase activity (n = 3 biological replicates; one-way ANOVA; ***p < 1.0 × 10−3, ****p < 1.0 × 10−4). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (right).

To further examine whether ETV2 regulates Rig1 gene expression, we used transcriptional assays. In these assays, we fused the 0.6 kb Rig1 promoter fragment, which harbored the ETV2 binding motif, to the luciferase reporter and transfected this construct with increasing amounts of ETV2. As outlined in Fig. 3c, we observed that ETV2 in a dose dependent fashion increased the luciferase reporter expression, which correlated to the activation of Rig1 gene expression. The ChIP-seq, EMSA and transcriptional assays support the notion that Rig1 is a direct downstream target of ETV2.

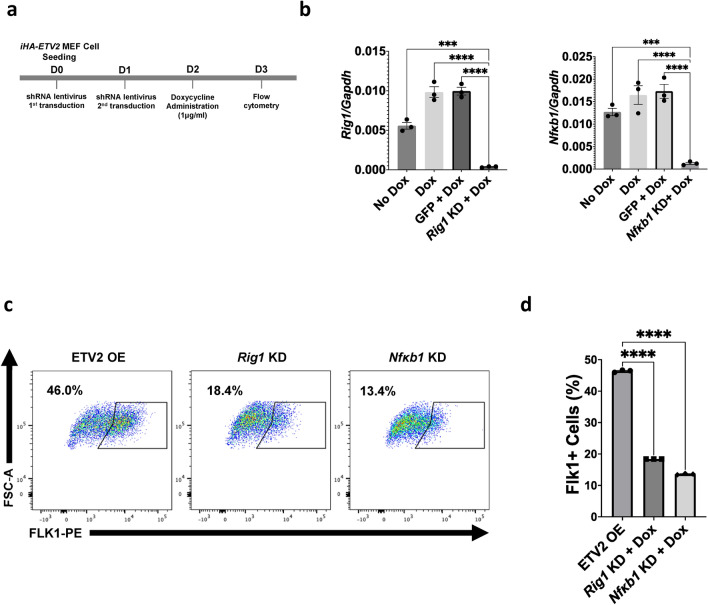

RIG1 signaling contributes to ETV2-mediated fibroblast to endothelial cell reprogramming

Having established that ETV2 induced RIG1 expression during endothelial reprogramming and that Rig1 was a direct downstream target for ETV2, we examined the impact of the RIG1 pathway during endothelial reprogramming. In these studies, we examined iHA-ETV2 MEF reprogramming under knockdown of RIG1 and RLR pathway effector protein NFκB1. We delivered selective shRNA lentiviral vectors to knockdown Rig1 and separately Nfκb1, two days prior to ETV2 (Dox) overexpression. The schematic of Rig1 shRNA lentivirus and doxycycline administration are outlined in Fig. 4a. iHA-ETV2 MEFs that were transduced with Rig1 and Nfκb1 shRNA lentivirus showed reduced Rig1 and Nfκb1 expression, respectively, as verified by qPCR (Fig. 4b). Upon reprogramming, transduced cells demonstrated reduced reprogramming into endothelial progenitor cells, as represented by the percentage of FLK1 expressing cells using flow cytometry analysis 24 h post-ETV2 overexpression (Fig. 4c,d). In these studies, ETV2-overexpressed iHA-ETV2 MEFs (treated with dox only) resulted in robust reprogramming of the MEFs to the endothelial lineage (47.23 ± 0.50% Flk1+ cells in the control group, n = 3). In contrast, ETV2-overexpressed iHA-ETV2 MEFs with Rig1 knockdown had a significant attenuation (20.90 ± 0.26% FLK1+ cells, n = 3) of ETV2 mediated reprogramming to the endothelial lineage. Additionally, ETV2-overexpressed iHA-ETV2 MEFS with Nfκb1 knockdown had 15.80 ± 0.06% Flk1 positivity (n = 3) for day 1. These studies provide further support that the RIG1 signaling pathway plays an important role in ETV2 mediated endothelial reprogramming.

Fig. 4.

Rig1 knockdown in iHA-ETV2 MEFs reduces reprogramming efficiency. (a) Schematic of Rig1 knockdown and ETV2 overexpression strategy that was used for iHA-ETV2 MEF reprogramming assay. (b) Relative expression level of shRNA lentivirus target—Rig1 and Nfκb1. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis (****p ≤ 0.0001). (c) Flow cytometry profile of ETV2-overexpressed MEFs at day 1 without Rig1 knockdown (left), with knockdown (middle), and with Nfκb1 knockdown (right). PE-conjugated FLK1 antibody was used to determine the percentage of reprogrammed cells. (d) Quantification (bar graph) showing the percentage of reprogrammed MEFs without Rig1 (Control) and with knockdown (Rig1, Nfκb1). Two-tailed unpaired t-test with unequal variances was used for statistical analysis (n = 3 for each group, ****p ≤ 0.0001). (n = 3 biological replicates; two-tailed unpaired t-test; ***p < 1.0 × 10−3, ****p < 1.0 × 10−4). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

To date, relatively few pioneer factors have been identified for mammalian lineage development and reprogramming. These pioneer factors bind to nucleosomal DNA, relax the chromatin landscape and recruit upstream factors to specify lineage development. In this capacity, these pioneer factors are at the top of the transcriptional hierarchy for specific lineages. Previous pioneer factors include: OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, GATA2, PDX1, ASCL1, FOXA1 and others including ETV29,30–35. Therefore, the mechanisms whereby these factors govern differentiation and reprogramming warrant further study in order to develop new regenerative therapies.

The present study highlights several important discoveries. The first discovery demonstrates, for the first time, the direct activation of RIG1 signaling response pathway by a pioneer factor for cellular reprogramming. The RIG1 pathway is part of the innate immune response against foreign single or double stranded RNA invasion. Upon the recognition of a foreign virus, pattern recognition receptors (PRR) such as RIG1 is activated to drive RLR signaling pathways to induce expression of type I interferons and proinflammatory cytokines24. Previous reports that focused on the additive effect of the PRR response in nuclear reprogramming demonstrated the activation of the PRR pathways as part of the immune response against the retroviral delivery vectors10,11 or microRNAs36,37. Indeed, administration of 5′ppp-dsRNA or control retroviral vector, both agonists of RIG1, have been shown to increase reprogramming in MEF cell lines with dox-inducible Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, cMyc expression system or cell permeant peptide-mediated stem cell generation that do not have RLR pathway activation11. However, in this study, scRNA-seq datasets of iHA-ETV2 MEFs showed that Rig1 transcript and RLR pathway transcripts were upregulated without the introduction of foreign RNA nor RIG1 agonist in the doxycycline-inducible ETV2 overexpression system. Importantly, the present studies confirmed that doxycycline administration itself did not trigger the RIG1 response using wild-type MEFs, which indicated that RIG1 expression was regulated by the overexpression of ETV2.

The second discovery, using an array of techniques, demonstrated that ETV2 was a direct upstream regulator of Rig1 gene expression. We and others have defined important downstream targets for ETV2 including: FLK1 (KDR), FLT1, GATA2, SHH, RHOJ, YES1, TIE2, CD31, CDH5 and others19,23,28,38–41. The definition of these ETV2 mediated transcriptional networks have enhanced our understanding of the role of this pioneer factor regarding cellular proliferation, epigenetic regulation, hematoendothelial lineage specification, cell migration, metabolic control, recruitment of specifying factors and other functions7,19,21,23,28,39–41. In the present study, we demonstrated a new role for ETV2 as a regulator of the RIG1 signaling pathway. Additional studies from our laboratory support the notion that ETV2 functions as an important regulator, more broadly, of related signaling pathways that includes Toll like receptors (TLRs). Further efforts are warranted to examine this role during hematoendothelial differentiation and reprogramming.

The third discovery that emerged from the present studies, was the impact of the RIG1 and NFκB on ETV2 mediated reprogramming of fibroblasts to the endothelial lineage. Although the activation mechanism differs from previous findings, RIG1 and NFκB appear to play important roles in endothelial reprogramming as we observed a dramatic decrease in the ETV2-mediated fibroblast to endothelial reprogramming rate following either the knockdown of Rig1 or Nfκb1. The underlying mechanisms regarding how RIG1 and/or NFκB functions during ETV2 mediated reprogramming to the endothelial lineage are limited as RIG1 and NFκB may impact or modulate endothelial reprogramming in parallel (via separate mechanisms) or in series via a common pathway. For example, previous studies have demonstrated that RIG1 may collaborate and interact with other context dependent factors (such as YY1) or RIG1/NFκB may function as part of a common pathway and impact reprogramming. A recent report demonstrated that RIG1 collaborated and recruited YY1, which resulted in increased expression of cardiomyocyte specific genes and reprogramming to the cardiomyocyte lineage36. Although these findings are limited to the cardiac reprogramming process, the mechanisms regarding the RIG1-YY1 interaction may play a role in reprogramming to other lineages. Alternatively, studies have suggested a role for RIG1 in the epigenetic modification process as the addition of the RIG1 agonist 5′ppp-dsRNA has been shown to increase H3K4me3 and decrease H3K27me3 in Sox2 and Oct4 promoters to promote fibroblast to iPSC reprogramming11. Additionally, given that the activation of the canonical RLR pathway is dependent on the conformational change of RIG1 upon binding to foreign RNA to interact with the downstream target protein, MAVS42,43, RIG1 may be affecting the ETV2-mediated reprogramming in a noncanonical manner in the absence of foreign RNA. Future studies will be needed to further define the role of these factors during ETV2-mediated endothelial reprogramming and during reprogramming to other lineages.

Although both Rig1 and Nfκb1 knockdown attenuated the ETV2-mediated reprogramming capability of fibroblasts, and NFκB is the downstream activator of the RLR pathway, we recognize the possibility that ETV2 could also be a direct upstream activator of NFκB expression. Typically, NFκB acts downstream of RIG1 in the RLR pathway, where RIG1 activation leads to the activation of NFκB through MAVS and other downstream signaling cascades. However, ETV2 ChIP-seq data and ATAC-seq data of reprogrammed MEFs suggest strong ETV2 binding to the Nfκb1 promoter, as well as upregulation of Nfκb1 upon ETV2 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 5). Separately, ETV2 was also shown to bind to the CXCL10 promoter. These experimental results support the notion that ETV2 can upregulate innate immunity through multiple modes of activation. These insights prompt further investigation into the mechanisms whereby ETV2 might transactivate NFκB, thereby influencing reprogramming.

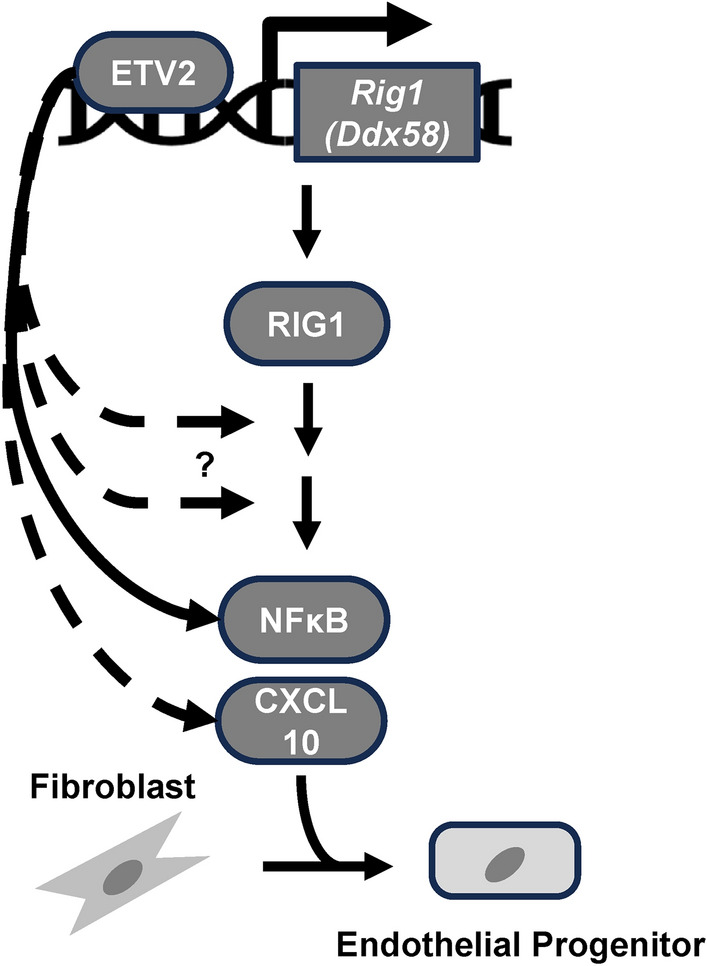

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that ETV2, a pioneer factor for the hemato-endothelial lineage, is a direct upstream regulator of Rig1 gene expression. Activation and induction of RIG1 and NFκB contribute to the ETV2-mediated fibroblast to endothelial cell reprogramming (Fig. 5). Our findings enhance our understanding of the multifaceted mechanisms of direct cellular reprogramming, highlighting the importance of RIG1 and NFκB. Further investigations into the precise mechanisms whereby inflammatory pathways impact epigenetic remodeling will be essential for harnessing the full potential of direct cellular reprogramming as a regenerative therapy.

Fig. 5.

Proposed model whereby ETV2-RLR pathway promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to the endothelial lineage. Dashed arrow indicates potential direct regulation of the genes of the respective proteins associated with the pathway.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Y.C., J.E.S.-P. and D.J.G. conceived the project and Y.C., S.D., J.E.S.-P., and D.J.G. wrote the manuscript. Y.C., S.D., and J.E.S.-P. designed the experiments. Y.C., X.M., W.G., and T.A.L. performed experiments. Y.C., J.E.S.-P., and S.D. analyzed the data. M.G.G., J.Z., H.A.S., S.D., and D.J.G. supervised the project. All authors commented on and edited the final version of the paper.

Funding

These studies were supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL148599; HL168647; P01HL160476), and the Department of Defense (PR200679).

Data availability

The scRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and ChIP-seq data for Etv2-mediated MEF reprogramming are deposited at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession no. GSE185684 (GSE168521, ChIP-seq of Etv2-induced MEF reprogramming; GSE168636, ATAC-seq of Etv2-induced MEF reprogramming; GSE185683, scRNA-seq of Etv2-induced MEFs reprogramming). All data will also be made available upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

Drs. Daniel J. Garry and Mary G. Garry are co-founders of NorthStar Genomics, LLC.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78115-w.

References

- 1.Wang, H., Yang, Y., Liu, J. & Qian, L. Direct cell reprogramming: approaches, mechanisms and progress. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Lee, S. et al. Direct reprogramming of human dermal fibroblasts into endothelial cells using ER71/ETV2. Circ. Res.120 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Morita, R. et al. ETS transcription factor ETV2 directly converts human fibroblasts into functional endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Garry, D. J. Etv2 is a master regulator of hematoendothelial lineages. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc.127, 212–223 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Soufi, A., Donahue, G. & Zaret, K. S. Facilitators and impediments of the pluripotency reprogramming factors’ initial engagement with the genome. Cell151, 994–1004 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wapinski, O. L. et al. Hierarchical mechanisms for direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to neurons. Cell155, 621–635 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gong, W. et al. ETV2 functions as a pioneer factor to regulate and reprogram the endothelial lineage. Nat. Cell Biol.24, 672–684 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koyano-Nakagawa, N. et al. Etv2 is expressed in the yolk sac hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors and regulates Lmo2 gene expression. Stem Cells30 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Sierra-Pagan, J. E. & Garry, D. J. The regulatory role of pioneer factors during cardiovascular lineage specification—A mini review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.9, 972591 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, J. et al. Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell151 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sayed, N. et al. Retinoic acid inducible gene 1 protein (RIG1)-like receptor pathway is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Stem Cells35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Zhou, H. et al. ZNF281 enhances cardiac reprogramming by modulating cardiac and inflammatory gene expression. Genes Dev.31, 1770–1783 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gascón, S. et al. Identification and successful negotiation of a metabolic checkpoint in direct neuronal reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell18, 396–409 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das, S. et al. ETV2 and VEZF1 interaction and regulation of the hematoendothelial lineage during embryogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.11 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Singh, B. N. et al. A conserved HH-Gli1-Mycn network regulates heart regeneration from newt to human. Nat. Commun.9, 4237 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiscornia, G., Singer, O. & Verma, I. M. Production and purification of lentiviral vectors. Nat. Protoc.1, 241–245 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sierra-Pagan, J. E. et al. FOXK1 regulates Wnt signalling to promote cardiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res.119, 1728–1739 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caprioli, A. et al. Nkx2-5 represses gata1 gene expression and modulates the cellular fate of cardiac progenitors during embryogenesis. Circulation123, 1633–1641 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh, B. N. et al. ETV2 (Ets variant transcription factor 2)-Rhoj cascade regulates endothelial progenitor cell migration during embryogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.40, 2875–2890 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh, B. N. et al. The Etv2-miR-130a network regulates mesodermal specification. Cell Rep.13, 915–923 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi, X. et al. The transcription factor Mesp1 interacts with cAMP-responsive element binding protein 1 (Creb1) and coactivates Ets variant 2 (Etv2) gene expression. J. Biol. Chem.290, 9614–9625 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmood, T. & Yang, P.-C. Western blot: technique, theory, and trouble shooting. North Am. J. Med. Sci.4, 429–434 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi, X. et al. Cooperative interaction of Etv2 and Gata2 regulates the development of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Dev. Biol.389, 208–218 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nan, Y., Nan, G. & Zhang, Y. J. Interferon induction by RNA viruses and antagonism by viral pathogens. Viruses6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kolli, D., Bao, X. & Casola, A. Human metapneumovirus antagonism of innate immune responses. Viruses4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Jaeger, M. et al. The RIG-I-like helicase receptor MDA5 (IFIH1) is involved in the host defense against Candida infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol.34, 963–974 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Val, S. et al. Combinatorial regulation of endothelial gene expression by ets and forkhead transcription factors. Cell135, 1053–1064 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koyano-Nakagawa, N. et al. Etv2 regulates enhancer chromatin status to initiate Shh expression in the limb bud. Nat. Commun.13, 4221 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lettice, L. A. et al. Opposing functions of the ETS Factor family define Shh spatial expression in limb buds and underlie polydactyly. Dev. Cell22, 459–467 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi, K. & Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell126, 663–676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, Y., Liu, Q., Zhou, Z. & Ikeda, Y. PDX1, Neurogenin-3, and MAFA: critical transcription regulators for beta cell development and regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther.8, 240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chanda, S. et al. Generation of induced neuronal cells by the single reprogramming factor ASCL1. Stem Cell Rep.3, 282–296 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vierbuchen, T. et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature463, 1035–1041 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cirillo, L. A. et al. Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol. Cell9, 279–289 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwafuchi-Doi, M. et al. The pioneer transcription factor FoxA maintains an accessible nucleosome configuration at enhancers for tissue-specific gene activation. Mol. Cell62, 79–91 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baksh, S. S., Hu, J., Pratt, R. E., Dzau, V. J. & Hodgkinson, C. P. Rig1 receptor plays a critical role in cardiac reprogramming via YY1 signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol.324 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Hodgkinson, C. P. et al. Cardiomyocyte maturation requires TLR3 activated NFκB. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio36, 1198–1209 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasmussen, T. L. et al. VEGF/Flk1 signaling cascade transactivates Etv2 gene expression. PloS One7, e50103 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koyano-Nakagawa, N. et al. Feedback mechanisms regulate Ets variant 2 (Etv2) gene expression and hematoendothelial lineages. J. Biol. Chem.290, 28107–28119 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh, B. N. et al. Etv2 transcriptionally regulates Yes1 and promotes cell proliferation during embryogenesis. Sci. Rep.9, 9736 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koyano-Nakagawa, N. & Garry, D. J. Etv2 as an essential regulator of mesodermal lineage development. Cardiovasc. Res.113, 1294–1306 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kowalinski, E. et al. Structural basis for the activation of innate immune pattern-recognition receptor RIG-I by viral RNA. Cell147, 423–435 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rehwinkel, J. & Gack, M. U. RIG-I-like receptors: their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat. Rev. Immunol.20, 537–551 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and ChIP-seq data for Etv2-mediated MEF reprogramming are deposited at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession no. GSE185684 (GSE168521, ChIP-seq of Etv2-induced MEF reprogramming; GSE168636, ATAC-seq of Etv2-induced MEF reprogramming; GSE185683, scRNA-seq of Etv2-induced MEFs reprogramming). All data will also be made available upon request.