Abstract

Eukaryotic cytochrome P450 enzymes, generally colocalizing with their redox partner cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) on the cytoplasmic surface of organelle membranes, often perform poorly in prokaryotic cells, whether expressed with CPR as a tandem chimera or free-floating individuals, causing a low titer of heterologous chemicals. To improve their biosynthetic performance in Escherichia coli, here, we architecturally design self-assembled alternatives of eukaryotic P450 system using reconstructed P450 and CPR, and create a set of N-termini-bridged P450-CPR heterodimers as the counterparts of eukaryotic P450 system with N-terminus-guided colocalization. The covalent counterparts show superior and robust biosynthetic performance, and the N-termini-bridged architecture is validated to improve the biosynthetic performance of both plant and human P450 systems. Furthermore, the architectural configuration of protein assemblies has an inherent effect on the biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged P450-CPR heterodimers. The results suggest that spatial architecture-guided protein assembly could serve as an efficient strategy for improving the biosynthetic performance of protein complexes, particularly those related to eukaryotic membranes, in prokaryotic and even eukaryotic hosts.

Subject terms: Protein design, Biocatalysis, Synthetic biology, Multienzyme complexes

Cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s) and their redox partner cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) often perform poorly in bioproduction of natural products by engineered prokaryotic microbes. Here, the authors report spatial architecture-guided P450-CPR assembly for improving the biosynthetic performance of both plant and human P450s in E. coli.

Introduction

Cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s) are biocatalysts of great industrial importance and extensively involved in the oxyfunctionalization of natural products1. In nature, P450s perform a broad range of metabolic chemistries2, participating not only in the formation of core skeleton molecules3 but also in the regio- and stereo-selective decoration of natural products4. For instance, three P450s are involved in the biosynthesis of salutaridine—the (R)-benzylisoquinoline scaffold of morphinan alkaloids in opium poppy, namely, CYP719B1 for the C-C coupling of (R)-reticuline5, CYP80B3 for hydroxylation6 and CYP82Y2 for dehydrogenation7, 8. Given that the naturally favored oxyfunctionalization of inert carbons under mild conditions with dioxygen1,9,10, P450s have great potential to enable the inaccessible chemical reactions to achieve in a readily scalable biochemical process, which is of particular interest in metabolic engineering for the economically feasible and ecologically sustainable bioproduction of natural products in microbes from simple and renewable feedstocks11–17.

However, the functional manipulation of P450s is challenging, especially those from eukaryotes. Eukaryotic P450s are microsomal monooxygenases, and belong to Class II P450 system specifically depending on the shared redox partner—reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR)—for electron transfer from NADPH18. CPR proteins sequentially transfer two electrons from NADPH via cofactors flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and flavin mononucleotide (FMN) to the P450 heme19. P450 and CPR of eukaryotic Class II P450 system generally reside in endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and colocalize on the cytoplasmic surface of the ER membrane through a short hydrophobic N-terminal anchor (NTA)20 (Fig. 1a). It has been reported that, in yeast, heterogenous P450s from plants or humans receive electrons from fungal CPR with a low efficiency21–23. While in E. coli, the components of eukaryotic P450 system have poor compatibility with the protein targeting machine of the bacterial host24. Therefore, these existing mismatches have caused eukaryotic P450 systems suffering from poor solubility, weak functionality and low turnover rate in microbes, especially in prokaryotic hosts such as E. coli.

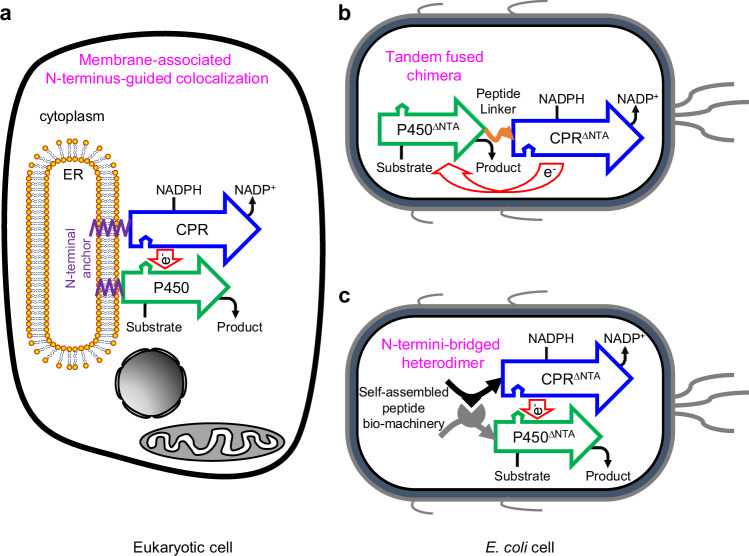

Fig. 1. Employing self-assembled peptide bio-machinery for spatial organization of eukaryotic P450 system.

a Eukaryotic P450 enzymes belong to Class II P450 system, in which P450 enzymes and their redox partner NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) generally colocalize on the cytoplasmic surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane through a short hydrophobic N-terminal anchor (NTA). b In E. coli, soluble cytoplasmic regions of eukaryotic P450 system are manipulated to form a functional chimera, using a flexible peptide linker indicated by the orange curve with a single arrow. c Self-assembled peptide bio-machinery, in this study, was harnessed to modularly reconstruct eukaryotic P450 system and finely tune the protein architecture in E. coli. The N-termini-bridged heterodimer was achieved via self-assembling the N-terminus-reconstructed P450 and CPR as a mimic counterpart of eukaryotic P450 system. The hollow arrow represents a polypeptide from the N-terminus to the C-terminus. The superscript ∆NTA indicates that the N-terminal anchor of the protein was truncated.

As a tractable host, E. coli is an attractive vehicle for P450 chemistry12. To date, in E. coli, two strategies have been developed for functionally organizing eukaryotic P450 system in vivo: (1) tandem fusion or (2) co-expression of the soluble cytoplasmic regions of both P450 and CPR. The former approach artificially combines the two protein regions to form a tandem fused P450-CPR chimera via mimicking the architecture of Bacillus megaterium CYP102A124 (Fig. 1b), which is a catalytically self-sufficient monooxygenase consisting of a P450 heme domain and a diflavin-containing CPR-like domain in a single polypeptide chain25. However, when one pathway comprises several P450s, for example, no less than eight P450s are involved in Taxol biosynthesis26, such chimeric approach requires that each of P450s should be fused with a CPR protein, making the molecular construction and subsequent optimization of P450-CPR chimeras labor-intensive. The other strategy achieves the functionality of eukaryotic P450 enzyme via co-expressing the N-terminus-modified P450 and CPR in a free-floating pattern. It has been found that the modification of native NTA is pivotal to the biosynthetic performance of eukaryotic P45015. For instance, an eight-residue peptide (8RP) originally derived from the N-terminus of bovine CYP17A1 has recently been found to promote CYP725A4-based taxadiene oxyfunctionalization, consequently improving the titer of oxygenated taxanes at least 10-fold in E. coli12.

In this work, we report that the membrane-imposed bonding of the native eukaryotic P450 system generates the N-terminus-guided colocalization pattern, resulting in a noteworthy geometric architecture between P450 and CPR. The engineered tandem chimera displays an apparently distinct architecture from the native eukaryotic P450 system due to the changes in the manner of spatial organization (Fig. 1a, b). Therefore, we speculate that the architecture for organizing P450 and CPR would play an indispensable role in controlling the biosynthetic capability of eukaryotic P450. Accordingly, we design several architectures for reconstructing eukaryotic P450 system, and assess the biosynthetic performance of the engineered P450s in the endomembrane-free prokaryote E. coli. In order to fine-tune the protein architecture, self-assembled peptide bio-machinery is harnessed to modularly reconstruct eukaryotic P450 system. We envision that an N-termini-bridged P450-CPR heterodimer derived from the self-assembly of N-terminus-reconstructed P450 and CPR would be achieved as a mimic counterpart of eukaryotic P450 system (Fig. 1c). We create a number of eukaryotic P450-CPR heterodimers with different architectures via peptide-mediated self-assembly in E. coli, and find that N-termini-bridged P450-CPR heterodimers are superior in the biosynthesis of plant natural product. Moreover, we demonstrate that this spatial architecture-guided protein assembly approach is adaptable to both plant and human P450 systems for improving the bioproduction of bio-chemicals in E. coli.

Results

The biosynthetic performance of plant CYP73A5 affected by the tandem architecture

To test the effect of the architecture of tandem fused chimeras on the biosynthetic performance of eukaryotic P450 in E. coli, we targeted the plant-specific CYP73A subfamily (Fig. 2a), which catalyzes the formation of p-coumaric acid from trans-cinnamic acid in the plant phenylpropanoid pathway27. Considering the different codon preference between the host and plants, we synthesized the E. coli codon-optimized coding sequences for Arabidopsis thaliana CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 (i.e. A. thaliana CPR2). Then, employing a flexible peptide linker24 as an inserted hinge, we fused CYP73A5Δ2-28 to either the N-terminus or the C-terminus of ATR2Δ2-77, and thus constructed two types of tandem fused chimeras: (i) CYP73A5Δ2-28-L-ATR2Δ2-77 and (ii) ATR2Δ2-77-L-CYP73A5Δ2-28 (Fig. 2b).

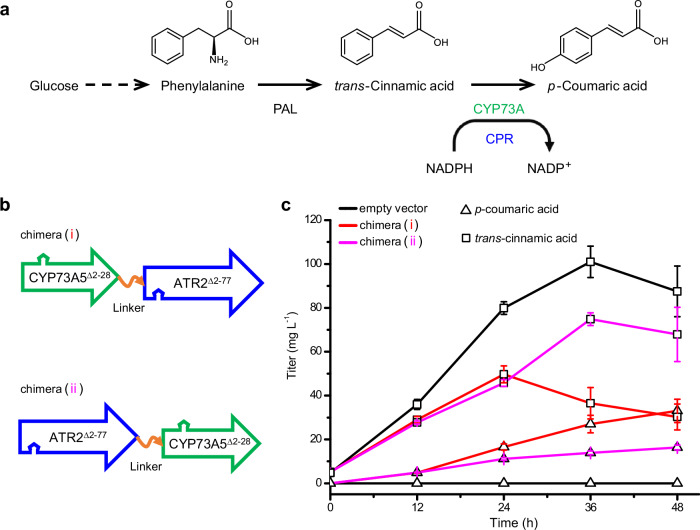

Fig. 2. Effects of the chimeric architecture on the biosynthetic performance of eukaryotic P450 enzyme.

a Plant p-coumaric acid biosynthesis, involving the plant-specific CYP73A subfamily along with CPR and the upstream phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), was targeted in prokaryotic E. coli. b Two types of tandem fused chimeras were constructed via fusing A. thaliana CYP73A5 in frame to either the N-terminus (i) or the C-terminus (ii) of A. thaliana P450 reductase 2 (ATR2) with a flexible peptide linker (L) as an inserted hinge, indicated by the orange curve with a single arrow. The N-terminal anchors of CYP73A5 (amino acid residues 2 to 28) and ATR2 (amino acid residues 2 to 77) were truncated. The arrow indicates a polypeptide from the N-terminus to the C-terminus. c p-Coumaric acid de novo biosynthesis (triangle) and trans-cinnamic acid accumulation (square) in A. thaliana PAL1-expressed E. coli strains with empty vector (black line), chimera (i) (red line), or chimera (ii) (magenta line). Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 9 biological independent clones). P value of p-coumaric acid titer at 48 hpi was calculated by two-sided t-test (P = 0.018). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Subsequently, the biosynthetic performance of both tandem fused chimeras was determined in a recombinant E. coli strain containing A. thaliana phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1 (AthPAL1), which can efficiently convert intracellular phenylalanine to trans-cinnamic acid in E. coli28 (Fig. 2a). The recombinant E. coli strain without the chimera could not biosynthesize p-coumaric acid but accumulated 87.51 mg L−1 trans-cinnamic acid at 48 h post-induction (hpi) (Fig. 2c), resulting in severe cell growth inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2c, at 48 hpi, the recombinant strain with chimera (i) produced 33.05 mg L−1 p-coumaric acid, which was 2.02-fold more than that of the recombinant strain with chimera (ii). The biomass-specific productivity of p-coumaric acid for the strains harboring chimera (i) or (ii) was 86 and 43 μg (g DW h)−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, in the medium of the recombinant strains with tandem fused chimera, trans-cinnamic acid was surplus in the range of 30.25 to 67.90 mg L−1 at 48 hpi (Fig. 2c).

It should be noted that the tandem fused chimera (i) CYP73A5Δ2-28-L-ATR2Δ2-77 had a similar arrangement of the catalytic domains to the bacterial CYP102A1, in which the P450 heme domain is also located in the N-terminus29. The result suggested that a nature-mimicking architecture for organizing eukaryotic P450 system would promote the biosynthetic performance of eukaryotic P450s even in a prokaryotic organism.

Architectural alternatives designed for plant CYP73A5 and ATR2 in E. coli

To expand the architectures for eukaryotic P450 system in E. coli, self-assembled peptide bio-machinery was harnessed to serve as a self-folded dual-track bridge to organize CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 in space at the post-translational level (Supplementary Fig. 2). Initially, a unique peptide ligation system SpySystem30, in which the side chains of Lys34 in SpyCatcher peptide and Asp7 in SpyTag peptide can post-translationally form an isopeptide bond, was adopted. By fusing SpyCatcher to CYP73A5Δ2-28 and SpyTag to ATR2Δ2-77 at either the N-terminus or the C-terminus, a set of heterodimers with distinct architecture could be generated due to the side chain self-assembly of SpySystem. As indicated in Fig. 3a, four CYP73A5Δ2-28-ATR2Δ2-77 heterodimers with different linkage architectures were created, of which all showed a molecular weight (MW) of about 130 KDa (Calculated MW = 139.7 KDa) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The target bands with the desired size were further identified by LC-MS/MS, showing that the matched peptides covered the full-length amino acid sequences in a range of 78%–85%. Moreover, all of the four components, i.e. SpyCatcher, SpyTag, CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77, were verified in each sample of interest (Supplementary Figs. 4–7), indicating that the reconstructed CYP73A5 and ATR2 were post-translationally assembled into a covalent heterodimer with a designed linkage architecture by virtue of the SpySystem. Heterodimer (I), CYP73A5Δ2-28SpyCatcher-SpyTagATR2Δ2-77, and heterodimer (II), ATR2Δ2-77SpyTag-SpyCatcherCYP73A5Δ2-28, were assumed to possess a similar architecture to the tandem fused chimeras (i) CYP73A5Δ2-28-L-ATR2Δ2-77 and (ii) ATR2Δ2-77-L-CYP73A5Δ2-28 (Fig. 2b), respectively. It’s worth noting that a C-termini-bridged heterodimer (III), CYP73A5Δ2-28SpyCatcher-ATR2Δ2-77SpyTag, and an N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV), SpyCatcherCYP73A5Δ2-28-SpyTagATR2Δ2-77, were also achieved, and the latter in AthPAL1-expressing E. coli was confirmed via Western blotting of the denatured whole-cell extracts (Supplementary Fig. 8 lane 1).

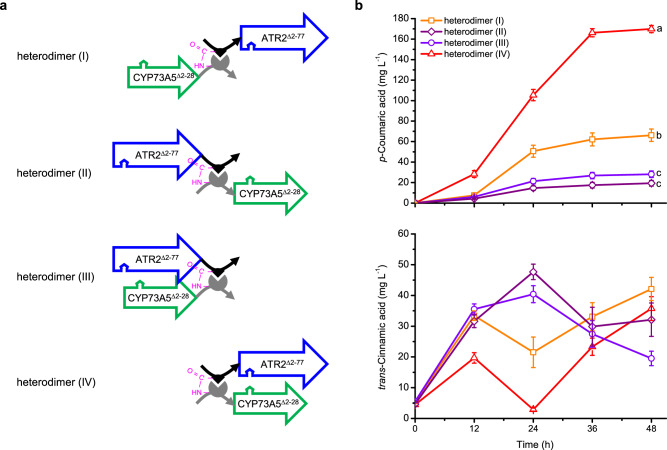

Fig. 3. Architectural organization of plant CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 based on self-assembled peptide bio-machinery in E. coli.

a The peptide ligation system SpySystem, spontaneously forming a post-translational intermolecular isopeptide bond (magenta) between the side chains of Lys34 in SpyCatcher peptide (gray) and Asp7 in SpyTag peptide (black)30, was harnessed to serve as a self-folded dual-track bridge to organize CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77. When SpyCatcher and SpyTag were respectively fused to the C-terminus of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and the N-terminus of ATR2Δ2-77, the covalent heterodimer (I) formed post-translationally. When SpyCatcher and SpyTag were respectively fused to the N-terminus of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and the C-terminus of ATR2Δ2-77, the covalent heterodimer (II) formed post-translationally. When SpyCatcher and SpyTag were respectively fused to the C-termini of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77, the covalent heterodimer (III) formed post-translationally. When SpyCatcher and SpyTag were respectively fused to the N-termini of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77, the covalent heterodimer (IV) formed post-translationally. The arrow indicates a polypeptide from the N-terminus to the C-terminus. b p-Coumaric acid de novo biosynthesis (upper panel) and trans-cinnamic acid accumulation (lower panel) of the AthPAL1-expressing E. coli strains with the heterodimer (I), (II), (III) or (IV). Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 11 (I), 10 (II), 12 (III), 12 (IV) biological independent clones). Significant differences (P < 0.05) of p-coumaric acid titer at 48 hpi are evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s new multiple range test and indicated by different lowercase letters. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Subsequently, the biosynthetic performance of these four heterodimers was tested in AthPAL1-expressing E. coli via fermentation as the tandem fused chimeras (Fig. 3b upper panel). Consistent with the results of the two tandem fused chimeras (Fig. 2c), the titer of p-coumaric acid with heterodimer (I) was higher than that with heterodimer (II), reaching 66.17 and 19.35 mg L−1 at 48 hpi, respectively. The strain with C-termini-bridged heterodimer (III) biosynthesized 28.14 mg L−1 p-coumaric acid, only 42.53% of the strain with heterodimer (I). As expected, the p-coumaric acid titer of the strain with N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV) was dramatically elevated to 169.85 mg L−1. And the biomass-specific productivity of p-coumaric acid for the strains harboring heterodimer (I), (II), (III) or (IV) was 192, 52, 85 and 563 μg (g DW h)−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Meanwhile, the accumulation of the P450 substrate in the medium was measured (Fig. 3b lower panel). The accumulation of trans-cinnamic acid was in an inverse proportion to the production of p-coumaric acid regarding to each heterodimer, especially at 24 hpi. The results suggested that, in the AthPAL1-expressing strains, the titer of p-coumaric acid could mirror the biosynthetic performance of the reconstructed CYP73A5, which was also in agree with the order of the biomass-specific productivity, i.e. heterodimer (IV) > heterodimer (I) > heterodimer (III) > heterodimer (II). The N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV), showing the highest p-coumaric acid output, may deploy a resemblant architecture to the membrane-associated N-terminus-guided colocalization of CYP73A5 and ATR2 on the ER membrane in plant cells31 (Figs. 1a and 3a). Hence, this peptide-based N-termini-bridged heterodimer of P450 and CPR might be considered as a mimic counterpart of eukaryotic membrane-bound P450 system. The in vivo results of the four heterodimers suggested that the architecture of protein assemblies would be exert an effect on the enzymatic activity of the reconstructed eukaryotic P450 system.

Enzyme kinetic assays of SpySystem-mediated CYP73A5-ATR2 heterodimers

To demonstrate the contribution of the architecture to the enzymatic activities of the reconstructed CYP73A5 enzymes, we further purified the SpySystem-appended CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 to depict the enzyme kinetics in vitro. SpyCatcherCYP73A5Δ2-28 and SpyTagATR2Δ2-77 were labeled with hexahistidine at N-terminus, while CYP73A5Δ2-28SpyCatcher and ATR2Δ2-77SpyTag were tagged with hexahistidine at C-terminus for polyhistidine affinity chromatography. To circumvent the potential effect of the histidine tag on enzymatic activity, the hexahistidine tag was sandwiched by a glycyl-seryl-seryl linker at N-terminus and a seryl-seryl-glycyl linker at C-terminus. As a control, CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 were respectively tagged with hexahistidine at N-terminus and also purified for enzyme kinetic assays.

The kinetic parameters of SpySystem-mediated CYP73A5-ATR2 heterodimers as well as the free-floating individuals (CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77) were quantified as the rate of p-coumaric acid generation in the presence of trans-cinnamic acid as specific substrate and NADPH as electron source. When at increasing concentrations of the substrate trans-cinnamic acid (Supplementary Fig. 9), the Km values of reconstructed CYP73A5 in the four heterodimers were all lower than the concentration of trans-cinnamic acid accumulated in the medium (Table 1, Fig. 3b lower panel), indicating that the in vivo trans-cinnamic acid might not be the limited factor for the bioproduction of p-coumaric acid. The kcat values of SpyCatcher-appended CYP73A5 in the heterodimer (I), (II), (III) and (IV) were 11.00-, 4.72-, 1.11- and 48.94-fold higher than that of the free-floating truncated CYP73A5, respectively (Table 1). The results confirmed that both the CYP102A1-like architecture and the N-termini-bridged architecture significantly improved the in vitro turnover number of the reconstructed CYP73A5, especially the nature-mimicking architecture of heterodimer (IV), which were consistent with much higher in vivo titer of p-coumaric acid observed in the strains harboring heterodimer (I) or (IV) (Fig. 3b upper panel).

Table 1.

Enzymatic assay of SpySystem-mediated CYP73A5Δ2-28-ATR2Δ2-77 heterodimers and the free-floating CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 with trans-cinnamic acid

| Proteins | trans-Cinnamic acida | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 min−1, × 103) | h | |

| CYP73A5Δ2-28 & ATR2Δ2-77 | 68.83 ± 14.37 | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.26 | 1.49 ± 0.39 |

| heterodimer (I) | 23.35 ± 5.88 | 0.198 ± 0.020 | 8.48 | 1.02 ± 0.23 |

| heterodimer (II) | 125.62 ± 151.95 | 0.085 ± 0.035 | 0.68 | 0.78 ± 0.34 |

| heterodimer (III) | 69.51 ± 20.16 | 0.020 ± 0.002 | 0.29 | 1.08 ± 0.24 |

| heterodimer (IV) | 62.98 ± 15.05 | 0.881 ± 0.090 | 13.99 | 1.08 ± 0.15 |

aThe Hill’s equation was used to fit the formation rate of p-coumaric acid to the concentrations of trans-cinnamic acid. h is the Hill coefficient. Data are shown as mean±SE (n = 3 independent experiments).

The enzymatic activities of the heterodimers were also assayed at increasing concentrations of the electron donor NADPH (Supplementary Fig. 10). As shown in Table 2, heterodimer (II) and (III), containing ATR2Δ2-77SpyTag component, presented a significantly reduced Km for NADPH, indicating that appending the peptide-based scaffold at the ATR2 C-terminus containing the NADPH-binding domain19 had a considerable effect on the electron donor access. In terms of the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km), the heterodimer (I), (II), (III) and (IV) were 2.84-, 2.76-, 0.52- and 10.88-fold of the dissociative form, respectively (Table 2). The results revealed that the nature-mimicking architecture of heterodimer (IV) strongly boosted the catalytic efficiency of reconstructed CYP73A5-ATR2 heterodimer. It should be noted that the fitting Hill coefficients were all greater than one, indicating that the NADPH-driven p-coumaric acid generation in the reconstructed CYP73A5-ATR2 system was a positive synergistic reaction, regardless of the architecture.

Table 2.

Enzymatic assay of SpySystem-mediated CYP73A5Δ2-28-ATR2Δ2-77 heterodimers and the free-floating CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 at increasing concentration of NADPH

| Proteins | NADPHa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 min−1, × 102) | h | |

| CYP73A5Δ2-28 & ATR2Δ2-77 | 171.60 ± 7.65 | 0.041 ± 0.001 | 2.39 | 1.68 ± 0.09 |

| heterodimer (I) | 235.91 ± 11.29 | 0.160 ± 0.005 | 6.78 | 2.84 ± 0.30 |

| heterodimer (II) | 48.56 ± 6.81 | 0.032 ± 0.001 | 6.59 | 1.88 ± 0.58 |

| heterodimer (III) | 64.18 ± 2.63 | 0.008 ± 0.0002 | 1.25 | 2.88 ± 0.36 |

| heterodimer (IV) | 261.97 ± 21.52 | 0.681 ± 0.036 | 26.00 | 1.97 ± 0.22 |

aThe Hill’s equation was used to fit the formation rate of p-coumaric acid to the concentrations of NADPH. h is the Hill coefficient. Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 3 independent experiments).

As is evident from Tables 1 and 2, the turnover number and catalytic efficiency of heterodimer (IV) with the N-termini-bridged architecture were 4.45 and 3.83 times, respectively, higher than those observed in heterodimer (I) with the CYP102A1-like architecture. Thus, the in vitro quantitative results clearly illustrated that the nature-mimicking N-termini-bridged architecture of heterodimer (IV) contributed to the reconstructed eukaryotic P450 system the highest turnover number and catalytic efficiency, even though the self-assembled bio-machinery for architecture generation, the peptide-based SpySystem herein, had an influence on substrate access and electron transfer between CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77.

Configurational modulation of N-termini-bridged CYP73A5-ATR2 heterodimer

To further explore whether the biosynthetic performance was affected by the architectural configuration of the N-termini-bridged heterodimer, we next swapped the N-terminal peptide appendixes between CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77. Hence, an alternative N-termini-bridged heterodimer (V), SpyTagCYP73A5Δ2-28-SpyCatcherATR2Δ2-77, was created with a different configuration from the N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV), SpyCatcherCYP73A5Δ2-28-SpyTagATR2Δ2-77, mentioned above (Supplementary Fig. 8 lane 2; Supplementary Fig. 11). Then, the biosynthetic performance of heterodimer (V) was compared to that of heterodimer (IV) in AthPAL1-expressing E. coli. As shown in Fig. 4 panel 1, the titer of p-coumaric acid with heterodimer (V) was diminished to 83.64 mg L−1 at 48 hpi, which was merely 49.24% of that with heterodimer (IV). The biomass-specific productivity of p-coumaric acid for the strain harboring heterodimer (V) was 50.80% of that observed for the strain with heterodimer (IV) (Fig. 4). The results indicated that the architectural configuration of the N-termini-bridged CYP73A5Δ2-28-ATR2Δ2-77 heterodimer based on SpySystem exerted a significant effect on the biosynthetic performance of the reconstructed eukaryotic P450 system in E. coli.

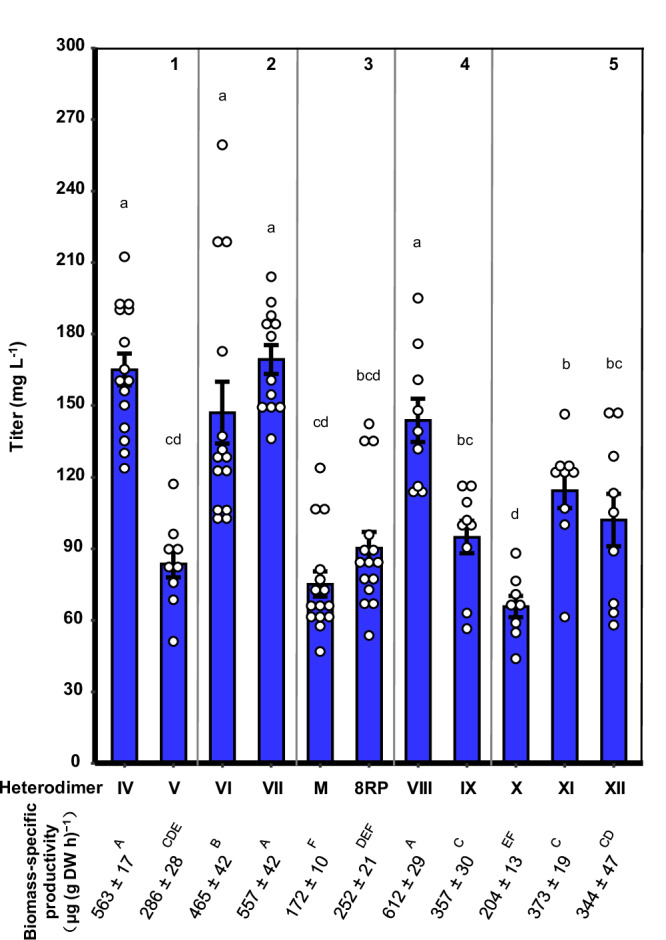

Fig. 4. Effects of the N-terminal peptide appendixes of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 on the bioproduction of p-coumaric acid in E. coli.

Panel 1 depicts the swapping of the peptide ligation system SpySystem between CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77. Panel 2 depicts an alternative self-assembly of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 based on the peptide ligation system SnoopSystem32 and the swapping of SnoopSystem between CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77. Panel 3 depicts the free-floating NTA-truncated CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77, including those modified with an 8RP octapeptide38. Panel 4 depicts the self-assembly of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 based on the interaction of the SH3 domain and the relevant SH3 ligand (SH3lig)40. Panel 5 depicts the site-directed mutation of SpySystem to abolish the formation of post-translationally covalent heterodimer. Heterodimer X contain SpyCatchermut while heterodimer XI with SpyTagmut. Heterodimer XII are introduced with both SpyCatchermut and SpyTagmut. SpyCatchermut and SpyTagmut indicate SpyCatcherE80Q and SpyTagD7A, respectively, with the isopeptide bond-forming amino acid substitution. Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 15 (IV), 9 (V), 14 (VI), 12 (VII), 15 (M), 15 (8RP), 9 (VIII), 9 (IX), 8 (X), 9 (XI), 9 (XII) biological independent clones). Significant differences (P < 0.05) in different N-terminal reconstructions are evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s new multiple range test and indicated by different lowercase letters (Titer) or different uppercase letters (Biomass-specific productivity). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Robust performance of N-termini-bridged CYP73A5-ATR2 heterodimer

To investigate the effect of the peptide scaffold on the biosynthetic performance of the N-termini-bridged heterodimers of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77, an alternative peptide ligation system SnoopSystem, of which SnoopCatcher and SnoopTag are able to form an intermolecular isopeptide bond spontaneously and post-translationally32, was applied. By pairwise appending SnoopCatcher peptide and SnoopTag peptide at both N-termini of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 to substitute SpySystem scaffold, two N-termini-bridged heterodimers, i.e. heterodimer (VI), SnoopCatherCYP73A5Δ2-28-SnoopTagATR2Δ2-77, and heterodimer (VII), SnoopTagCYP73A5Δ2-28-SnoopCatherATR2Δ2-77, were further created (Supplementary Fig. 8 lane 3 and 4; Supplementary Fig. 12).

The biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged heterodimers (VI) and (VII) was also assessed in AthPAL1-expressing E. coli. The titer of p-coumaric acid with heterodimer (VI) was 146.97 mg L−1 while that with heterodimer (VII) was 169.33 mg L−1 at 48 hpi (Fig. 4 panel 2). The biomass-specific productivity of p-coumaric acid for the strains harboring heterodimer (VI) or (VII) was 465 and 557 μg (g DW h)−1, respectively (Fig. 4). Quantitatively, the highest in vivo output of N-termini-bridged heterodimers based on SnoopSystem was comparable to that of heterodimers based on SpySystem (Fig. 4 panel 1 and 2). These results confirmed that the biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged CYP73A5Δ2-28-ATR2Δ2-77 heterodimers were robust, regardless of the covalent self-assembled peptide bio-machineries SpySystem or SnoopSystem employed in our experiments. Notably, unlike the N-terminal SpySystem swapping leading to a dramatical gap in the titer of p-coumaric acid (Fig. 4 panel 1), the N-terminal SnoopSystem swapping resulted in a much lower titer margin (Fig. 4 panel 2). The result suggested that SnoopSystem-based N-termini reconstruction of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 might endow the N-termini-bridged heterodimers with an enhanced structural fitness.

Superior performance of N-termini-bridged CYP73A5-ATR2 heterodimer

Considering that there are protein-protein interactions between P450 and its redox partner in eukaryotic cells33–37, we were wondering that whether altering both N-terminus-appended peptides of CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 affect the biosynthetic performance of the heterologous P450 in E. coli. We started with the free-floating NTA-truncated CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77. While both truncated individuals were co-expressed in AthPAL1-expressing E. coli, the titer of p-coumaric acid was 75.16 mg L−1 at 48 hpi (Fig. 4 panel 3 M). Subsequently, we appended both CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 at N-terminus with an octapeptide 8RP, which has been optimized at both codon level and amino acid level for the expression of eukaryotic P450s in E. coli38, 39 and is usually applied as an N-terminal modification element in P450-involved bioproduction of chemicals12, 14, 15. As shown in Fig. 4 panel 3, the N-terminal 8RP modification brought the titer of p-coumaric acid up to 90.29 mg L−1, 1.2-fold of that obtained with the NTA-truncated individuals. These results indicated that the biosynthetic performance of the free-floating CYP73A5 and ATR2 with NTA truncation or N-terminal 8RP modification were merely 44.25% and 53.16%, respectively, of the biosynthetic ability of the SpySystem-mediated N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV) (Fig. 3b).

We further attempted to tether CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 as a noncovalent N-termini-bridged heterodimer by taking advantage of the mouse SH3 domain and its high-affinity peptide ligand (SH3lig) (Kd = 0.1 μM)40. By N-terminal appending and swapping, two adhesive N-termini-bridged heterodimers were supposed to form post-translationally and named as heterodimer (VIII), SH3ligCYP73A5Δ2-28/SH3ATR2Δ2-77, and heterodimer (IX), SH3CYP73A5Δ2-28/SH3ligATR2Δ2-77. When heterodimer (VIII) or heterodimer (IX) was introduced into AthPAL1-expressing E. coli, the titer of p-coumaric acid was 143.82 or 94.83 mg L−1 at 48 hpi, respectively (Fig. 4 panel 4). Thus, the biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged heterodimer (VIII) and (IX) with SH3/SH3lig pair were 1.91- and 1.26-fold of the free-floating NTA-truncated CYP73A5 and ATR2, respectively (Fig. 4 panel 3 and 4). The results further confirmed that the N-termini-bridged architecture improved the biosynthetic performance of plant P450 system in E. coli, and also indicated that the architectural configuration of the N-termini-bridged CYP73A5Δ2-28-ATR2Δ2-77 heterodimer based on the SH3/SH3lig system effected the biosynthetic performance of the reconstructed eukaryotic P450 systems in E. coli. Whereas compared to the biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV) based on the covalent SpySystem, those of N-termini-bridged heterodimer (VIII) and (IX) with noncovalent SH3/SH3lig system were 84.67% and 55.83%, respectively (Figs. 3b and 4 panel 4). The results suggested that covalent tethering could improve the in vivo biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged P450-CPR heterodimer in E. coli.

And then, we tested the role of the covalent isopeptide bond of the SpySystem in improving the biosynthetic performance of N-termini-bridged heterodimer (IV). To abrogate the isopeptide bond, the participant amino acids in SpyCatcher (E80Q) and/or SpyTag (D7A)30 were substituted via site-directed mutation, resulting in the absence of the covalent heterodimer (IV) (Supplementary Fig. 8 lane 9). As shown in Fig. 4 panel 5, the titer of p-coumaric acid dropped to 65.71 mg L−1 (heterodimer X with SpyCatcherE80Q), 114.38 mg L−1 (heterodimer XI with SpyTagD7A) and 101.99 mg L−1 (heterodimer XII with both SpyCatcherE80Q and SpyTagD7A), which were 38.69%, 67.34% and 60.05% of heterodimer (IV), respectively. Among these heterodimers with N-terminus-appended deficient SpySystem, the heterodimer with SpyCatcher and mutated SpyTagD7A showed the highest titer and biomass-specific productivity (Fig. 4), probably due to the high affinity (Kd = 0.2 μM) between SpyCatcher and SpyTagD7A30.

These results further confirmed that N-terminal tethering of plant P450 and the redox partner was beneficial to improve the biosynthetic performance of the eukaryotic P450 enzyme in E. coli, and also indicated that the reconstructed plant P450 system with N-terminal covalent joint, such as the heterodimers (IV) and (VII), possessed superior performance, suggesting that the mechanical stability of the self-assembled peptide bio-machinery, employed for spatially organizing a multienzyme cascade bioreactor, could have a considerable effect on the efficiency of bioproduction.

N-termini-bridged protein self-assembly adaptable to improve the biosynthetic performance of human P450 system in E. coli

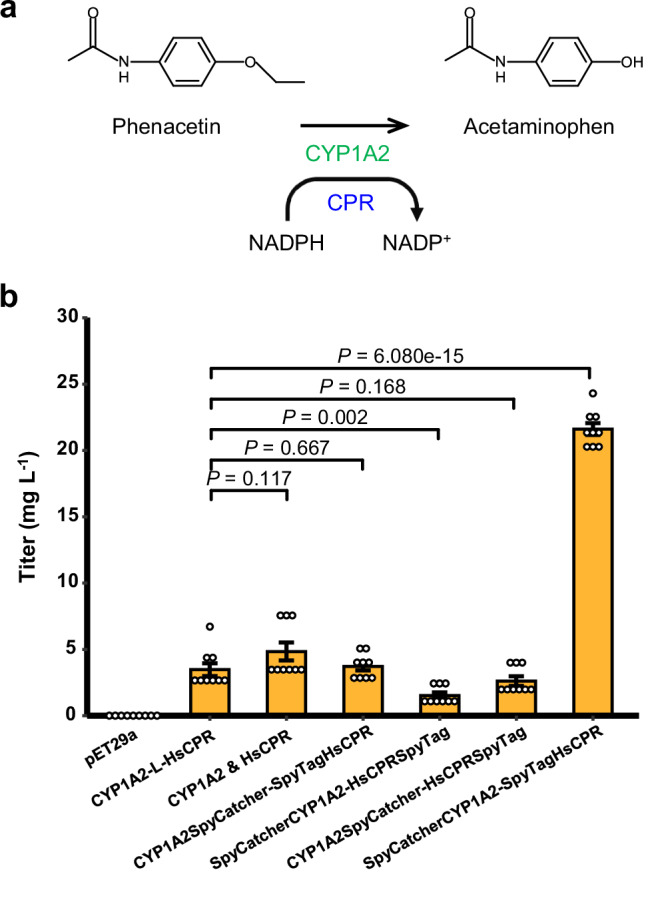

Furthermore, we examined the effect of architectural organization on the biosynthetic performance of animal P450 system in E. coli. Human CYP1A2, one of the major oxidative drug-metabolizing enzymes in liver41–43, was chosen for the drug metabolite bioproduction. According to the spatial organization of the plant CYP73A5Δ2-28 and ATR2Δ2-77 described above, the NTA-truncated CYP1A2Δ2-37 and HsCPRΔ2-52 were architecturally organized with the self-assembled peptide bio-machinery SpySystem (Supplementary Fig. 13a−d). Meanwhile, CYP1A2Δ2-37 was also expressed in a tandem pattern at N-terminus of HsCPRΔ2-52 (Supplementary Fig. 13e), or co-expressed with HsCPRΔ2-52 individually (Supplementary Fig. 13f).

To assess the biosynthetic performance of CYP1A2 variants, the bioproduction of the analgesic drug acetaminophen from phenacetin was carried out via whole-cell biotransformation (Fig. 5a). The product of CYP1A2 variant was confirmed to be authentic acetaminophen, whereas E. coli strain with empty vector was of inability to biosynthesize acetaminophen from phenacetin. As shown in Fig. 5b, the strain with the CYP102A1-like tandem chimera, CYP1A2Δ2-37-L-HsCPRΔ2-52, produced 3.47 mg L−1 acetaminophen, while the strain with the free-floating individuals, CYP1A2Δ2-37 and HsCPRΔ2-52, produced 4.84 mg L−1 acetaminophen. Regarding the SpySystem-organized heterodimers, the strain with the CYP102A1-like heterodimer, CYP1A2Δ2-37SpyCatcher-SpyTagHsCPRΔ2-52, produced 3.73 mg L−1 acetaminophen, which was comparable to the output of the strain with the CYP102A1-like chimera. Obviously, the strain harboring the N-termini-bridged heterodimer, SpyCatcherCYP1A2Δ2-37-SpyTagHsCPRΔ2-52, produced the most acetaminophen, which was 21.61 mg L−1. The results indicated that the SpySystem-based counterpart of human CYP1A2 and CPR system showed 6.23-fold higher biosynthetic performance than the CYP102A1-like chimera in E. coli, and also confirmed that the N-termini-bridged architecture favored human P450 system for bioproduction in space. Therefore, these results indicated that the N-termini-bridged protein self-assembly strategy was feasible and adaptable to organize human P450 system to improve the bioproduction of drug metabolites in E. coli.

Fig. 5. Spatial organization of human P450 system for acetaminophen bioproduction in E. coli.

a Human CYP1A2 was reconstructed with the redox partner CPR for the bioproduction of acetaminophen via phenacetin O-deethylation, a marker reaction of CYP1A2. b CYP1A2-mediated acetaminophen bioproduction. The recombinant E. coli strain with the empty vector was used as a control. Human CYP1A2 and CPR, of which NTA were truncated, were expressed either as a CYP102A1-like chimera or free-floating individuals. And also, based on the self-assembled peptide bio-machinery SpySystem, NTA-truncated CYP1A2 and CPR were organized to form four heterodimers. Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 9 biological independent clones). P value was calculated by two-sided t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The physical association among proteins is ubiquitous in metabolic systems. Metabolite channeling, which involves the assembly and disassembly of metabolic enzymes, is considered as one of the significant contributions of protein-protein interactions44. In this study, we have demonstrated that the architectural organization of proteins tethered in space facilitates the formation of electron channeling in eukaryotic P450 systems, thereby improving the bioproduction of phytochemicals and human drug metabolites in a prokaryotic host.

Proteins form dynamic protein assemblies necessary to perform specific functions in cells. Natural protein assembly offers many intrinsic advantages including enhanced stability, controllable stoichiometry, activity regulation, functional coupling, metabolite channeling, redox homeostasis, spatiotemporal organization, and genetic robustness and plasticity, thus efficiently participating in global metabolic network45. In eukaryotic cells, membrane-anchored proteins usually have physical associations in the crowded habitats, where numerous functional links occur via membrane fluidity and protein-protein interactions. However, the contact between eukaryotic membrane proteins, such as the P450s and their shared cognate electron-transferring partner proteins, is generally weak but beneficial to organize an incompact encounter complex. Notably, there is a 15- to 20-fold excess of P450 enzymes over the shared redox partner in the liver microsomes46–48, even though the NADPH-driven dual-electron oxyfunctionalization performed by P450 enzymes requires both protein components assembling a functional transient complex with a molar ratio of 1:149. Hence, the partnerships among the redox partner and P450 enzymes can dynamically shift depending on the required intracellular function50. Due to the incompatible membrane signals, eukaryotic P450 systems are usually heterogeneously expressed in the absence of N-terminal membrane-embedded regions in prokaryotic cells51. Herein, by expressing in a free-floating pattern, the cytoplasmic regions of either plant or human P450 systems formed functional protein assemblies in E. coli (Fig. 4 panel 3 and Fig. 5). Compared to the corresponding tandem fusions, both plant and human P450 systems expressed in the free-floating pattern showed higher biosynthetic performance in E. coli (Figs. 2, 4 and 5). These strongly suggest that a proper geometry structure, forming during the spontaneous protein assembly, is crucial in ensuring a favorable electron channeling in eukaryotic P450 systems. In the structural dynamics, protein assembly for the efficient function coupling is probably accessible while using the uncommitted components; nevertheless, it is potentially restricted in space when the components are tandem fused. To improve the engagement of these free-floating engineered membrane proteins, modifying their N-terminal regions can enhance the reactive performance of eukaryotic P450 enzymes in prokaryotic cells12, 52. In our efforts, through N-terminal reconstruction using the self-assembled peptide bio-machinery, such as SpySystem and SnoopSystem for N-terminal covalent bridging and SH3/SH3lig for N-terminal affinitive adhesion, we observed significantly improved biosynthetic performance of the protein assemblies of plant CYP73A5 and ATR2 (Fig. 4 panels 1, 2 and 4). The results indicate that establishing a firm N-terminal tethering between eukaryotic P450 enzyme and its redox partner can not only strengthen their association but also enhance the biosynthetic performance of eukaryotic P450 system. This finding was further validated with human P450 system, tethered by SpySystem, for the bioproduction of drug metabolite in E. coli (Fig. 5).

The biological activity of protein assemblies depends on the geometric architecture of the enzyme complexes. In nature, protein assemblies exhibit a remarkable structural diversity as a result of the thermodynamic folding of the components and various protein-protein interactions53–55. Herein, by appending the BioBricks of self-assembled peptide bio-machinery to N-terminus or C-terminus of eukaryotic P450 system, four stable protein assemblies with distinct architectures were achieved. As depicted in Figs. 3 and 5, among the four SpySystem-based architectures, the N-termini-bridged geometry endowed eukaryotic P450-CPR assemblies the highest biosynthetic performance in E. coli, no matter that plant or human P450 system was organized. Whereas protein assembly is susceptible to the environment and concentration of the components, the in vitro quantitative enzymatic assays indicated that the peptide-based geometric architecture had an influence on substrate access of eukaryotic P450 system, and further confirmed that the N-termini-bridged architecture dramatically boosted the turnover number and catalytic efficiency of plant P450-CPR assemblies (Tables 1 and 2). Presumably, on one hand, a quaternary structure of eukaryotic P450-CPR complex assembled in the N-termini-bridged architecture in E. coli resembles a native membrane-bound P450-CPR complex in eukaryotic cells, facilitating substrate access and electron transfer-required conformation change. On the other hand, the N-terminal tethering reinforces the protein-protein interactions of the reconstructed eukaryotic P450 system, and may promote the association of the cofactor-binding domains, consequently favoring the formation of electron channeling.

It’s worth noting that, the configuration of the tethered protein components on the peptide-based scaffold has an inherent role in the output of the engineered assemblies. In regard to the distinguished N-termini-bridged architectures, the swapping of the N-terminus-appended peptide BioBricks of the SpySystem resulted in a 50.76% decline in the biosynthetic performance of plant CYP73A5-CPR assemblies (Fig. 4 panel 1); swapping the BioBricks of the SnoopSystem or the SH3/SH3lig led to a reduction of 13.20% and 34.06%, respectively (Fig. 4 panels 2 and 4). The robust biosynthetic performance of SpySystem- and SnoopSystem-tethered CYP73A5-ATR2 assemblies (Fig. 4 panels 1 and 2) indicates that the biosynthetic performance of the engineered assemblies depends on the forming geometric structure rather than the possible changes in the expression level of the reconstructed components, resulted from the swapping of N-terminal peptide BioBricks. The results demonstrate that a well-designed architecture, in terms of the configuration, can impose spatial constraints on either the structural docking of the protein assemblies or the conformational flexibility of the redox partner required for the long-distance electron transfer in eukaryotic P450 system. The potentially spatial constraints may be resolved via optimizing the linkers between the BioBricks of self-assembled peptide bio-machinery and eukaryotic P450 system. What’s suggested in the context is that when protein complex is organized in space, the natural topology structure should be considered in priority to learn for designing the spatial architecture of the reconstructed protein assemblies, of which the configuration should not be excluded meanwhile.

The engineered covalent protein assembly paves an alternative way to investigate and unravel the structure-function relationships of membrane protein complexes with various spatial architectures. The membrane-associated protein assemblies are often dynamic and difficult to separate and purify, causing the structure of membrane protein complexes hard to access in practice56. Outside the native membrane, membrane proteins often suffer from low expression, poor solubility and high instability, making their recombinant production and structural characterization challenging57. Aiming at the membrane anchors, the peptide-based covalent protein assembly can build the counterparts of the membrane protein complexes with some kind architectures, and enable the researchers to purify the reconstructed protein complexes via incorporating a proper affinity tag, offering an opportunity to characterize their structures. The structural characterization of the engineered protein assemblies would be conducive to appreciate key protein-protein interactions, and elucidate molecular mechanisms in the geometric organization of protein assemblies.

We have modularly and successfully reconstructed the Class II P450 system from plants and humans by taking advantage of the post-translational self-assembly approach to form a type of N-termini-bridged heterodimers for improving the P450-involved bioproduction of chemicals in a prokaryotic host. Our results have shown that an architectural and biosynthetic orchestration of eukaryotic P450 system is achieved in E. coli. Therefore, based on the CPR-shared characteristic of eukaryotic P450 system, such a modular spatial architecture-guided protein assembly approach should enable the efficient bioproduction of chemicals, of which the biosynthetic pathway involves two or even more P450 enzymes.

Methods

Plasmids and bacterial strains

All plasmids and strains used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2, respectively. During the construction of the plasmids, DNA fragments were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the relevant primer pairs listed in Supplementary Data 3 and were assembled into restriction endonuclease-digested p15A-trcOAthPAL128, pET29a or its derivatives with a one-step cloning method using the ClonExpress One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). The sequences of these synthesized PCR templates optimized for E. coli expression are listed in Supplementary Data 4. For in-frame gene fusion in the DNA assembly process, the termination codon TAA of the prefixed gene and the initiation codon ATG of the following gene were deleted in the primers. All of the fusion genes constructed in this study were verified by DNA sequencing, and the encoded amino acid sequences are listed in Supplementary Data 5. In all DNA manipulations, Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, and 10 g L−1 NaCl, pH 7.2) was used. Antibiotics were added if necessary (kanamycin 50 μg mL−1, tetracycline 25 μg mL−1 and spectinomycin 100 μg mL−1).

p-Coumaric acid de novo biosynthesis

Frozen glycerol stocks of recombinant E. coli strains were thawed and streaked on LB agar plates. Three randomly picked single clones of each recombinant strain were independently incubated in 3 mL of LB medium with suitable antibiotics at 37 °C at 200 rpm for 8 h. Then, 2.5 mL of each cell culture was transferred into 50 mL of fermentation medium28 in a 250 mL baffled shake flask and grown at 37 °C and 120 rpm. Upon reaching an OD600 of approximately 0.6, the cells were induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and the de novo biosynthesis of p-coumaric acid was initiated at 30 °C and 200 rpm. The medium was maintained at approximately pH 7.0 by adding ammonium hydroxide periodically. Samples were taken at an interval of 12 h, added with an equal volume of methanol to terminate the reaction, and then analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Expression and purification of SpySystem-reconstructed CYP73A5 and ATR2

E. coli BL21(DE3) was used to express the hexahistidine-labeled SpySystem-appended CYP73A5 and ATR2 for protein purification. Cells were grown at 37 oC and 200 rpm in LB medium containing kanamycin to OD600 of 0.4–0.6, and then were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG at 16 oC and 120 rpm for 20 h. When CYP73A5 derivatives were induced, 0.5 mM 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) was added. About 400 mL cell cultures were then harvested by centrifugation at 6439 × g and 4 oC for 5 min, and resuspended with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in 40 mL Buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl). Cell suspension was disrupted in an ice-water bath at 250 W for 30 min with a 1 sec short burst followed by 3 sec rest for cooling using a JY92-2D sonifier (Scientz Biotech, Ningbo, China). The soluble protein, present in the supernatant after centrifugation at 14,489 × g and 4 °C for 30 min, was applied for ÄKTA pure 25 M1 protein purification system with a 5 mL HisTrapTM HP affinity column (Cytiva, MA, USA). Buffer A and Buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole) were used to wash non-specifically bound proteins and elute the His-tagged target protein via gradually increasing the ratio of Buffer B in the system buffer. The target protein was desalted into Buffer A with a 5 mL HiTrapTM desalting column (Cytiva, MA, USA). The target proteins were condensed into stock solution (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol) at 3,000 × g and 4 °C with an Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter Ultracel®-10 KDa for CYP73A5s and Ultracel®-30 KDa for ATR2s (Merck Millipore, Ireland). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford’s assay58.

Kinetic assay of SpySystem-reconstructed CYP73A5 and ATR2

The steady-state kinetics experiments of SpySystem-reconstructed CYP73A5 and ATR2 were performed with trans-cinnamic acid and NADPH as substrates via monitoring the formation of p-coumaric acid with HPLC. The reaction was conducted in 200 μL Buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5) with 2 μM FMN (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The components of one heterodimer were premixed at an equal concentration of 10 μM at 30 °C for 30 min, and then added to the reaction system with a final concentration of 1 μM. The characterization of SpySystem-reconstructed CYP73A5s was initiated by 1 mM NADPH with the use of 20 mM NADPH stock solution (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). While SpySystem-reconstructed ATR2s were characterized with 500 μM trans-cinnamic acid (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and triggered by NADPH addition. The reaction system was incubated in 30 °C for 10 min, and then methanol was added to a final concentration of 20% (v/v) to quench the reaction for HPLC analysis.

Acetaminophen bioproduction

Acetaminophen was produced via whole-cell biotransformation using human CYP1A2 in vivo in an NADPH supply-reinforced E. coli strain harboring the plasmid pSC101-anti(sthA)-OE(pntAB) constructed previously28. The recombinant strains harboring the plasmid with the genes encoding the reconstructed CYP1A2 and HsCPR were picked, inoculated, and cultured as the strains for p-coumaric acid described above, except for the addition of 0.5 mM 5-ALA in the medium. After induction with 0.1 mM IPTG for 15 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2515 × g for 5 min, washed twice and resuspended in 15 mL biotransformation buffer to an OD600 of 50. The biotransformation buffer contained 100 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propane sulfonic acid (MOPS), 28.71 mM K2HPO4, 25.72 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM citric acid, 5 mM MgSO4, 277.78 mM glucose, and 0.02 mM phenol red (pH 7.0). Then, 300 μM phenacetin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the resuspended cells to trigger acetaminophen bioproduction at 30 °C with a stirring rate of 200 rpm. The transformation system was maintained at approximately pH 7.0 by periodically adding ammonium hydroxide. Samples were taken with an interval of 2.5 h, mixed with a half volume of methanol to quench the reaction, and then subjected to HPLC analysis. The biotransformation was performed for 7.5 h.

Protein identification

The cell pellets induced for 12 h were washed twice, resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer, and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The target bands were cut off from the gel, cleaved by trypsin, and then subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano system interfaced with Q Exactive mass spectrometer (both ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Nanospray Flex ion source was equipped for the generation of nano-electrospray. Samples were loaded into a nanoViper C18 trap column (Acclaim PepMap 100, 75 μm × 20 mm) and separated on an Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 column (75 μm × 250 mm packed with 2 μm, 100 Å) (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The desalting procedure was performed with 20 μL mobile phase A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid). The elution was started with phase B (80% (v/v) acetonitrile, 0.1% (v/v) formic acid) at 5% in a gradient as follows: 0–5.1 min, 5% B (isocratic); 5.1–12 min, 5–40% B (linear); 12–14 min, 40–95% B (linear); 14–20 min, 95% B (isocratic); 20–20.1 min, 95–5% B (linear). The flow rate was 0.3 μL min−1. The ion spray voltage was 1.9 kV, and the interface heater temperature was set at 320 °C. Tandem MS data were collected in data-dependent acquisition mode with a full MS survey scan (scan range: 350–2000 m/z; resolution: 70,000; automatic gain control (AGC) target value: 3 × 106; maximum injection time: 100 ms) and 20 MS2 scans (AGC target value: 1 × 105; maximum injection time: 50 ms). The MS2 spectra were acquired in the ion trap in rapid mode, and only spectra with a charge state of 2–5 were selected for fragmentation by higher-energy collision dissociation with a normalized collision energy of 28 eV. Dynamic exclusion was used to remove unnecessary MS/MS information and set as follows: exclude isotope on, duration 25 s and peptide match preferred. The MS/MS data were processed in ProteoWizard (3.0.10577 64-bit)59, and then analyzed using Mascot V2.3.02 (Matrix Science, London, UK) for the protein identification. Trypsin was used as the enzyme definition, allowing two missed cleavages. Carbamidomethylation (C) was specified as a fixed modification. Acetylation (Protein N-term), Oxidation (M), Deamidation (NQ), pyro-Glu from Gln (N-term Q) and pyro-Glu from Glu (N-term E) were specified as variable modifications. Parent ion tolerance was set to 10 ppm while fragment ion mass tolerance was 0.05 Da.

Western blotting was performed according to the protocol60–62. Specifically, the primary antibody used for reconstructed CYP73A5s with 2×Flag tag was anti-FLAG tag mouse monoclonal antibody #D191041 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and the dilution ratio was 1:4000. The primary antibody used for reconstructed ATR2s with octohistidine tag was anti-6×His tag mouse monoclonal antibody #D191001 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) with a dilution ratio of 1:4000. The second antibody was horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG #D110087 from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) at a concentration of 1:5000 recommended by the manufacturer. The chemiluminescent substrate 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) of HRP was used to detect the target proteins at a concentration of 0.1 mg L−1 with 0.3‰ (v/v) hydrogen peroxide. The blotted membrane was imaged with Tanon 5200 Multi imaging system (Shanghai, China), and the integrated density of the target bands was measured using the ImageJ software63.

Sample analysis

Biomass was detected by measuring the optical density (OD) of the diluted suspensions at 600 nm with a spectrophotometer (MAPADA Instruments, Shanghai, China). Wet weight (WW) and dry weight (DW) of 1 OD600 cells were 1.70 and 0.39 g L−1, respectively. All samples taken from the cultures were centrifuged at 14,489 × g for 2 min, and the supernatants were used for measuring glucose with the SBA-40D biosensor analyzer according to the manufacturer’s specification (Institute of Biology, Shandong Academy of Sciences, Jinan, China). Samples with methanol were centrifuged at 14,489 × g for 5 min. After filtered through a 0.22 μm polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) filter, the supernatants were analyzed and quantified by HPLC (Shimadzu LC-20A, Kyoto, Japan) with a reversed-phase Shimadzu InertSustain C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) and a Shimadzu SPD-M20A photodiode array detector. The mobile phase used for p-coumaric acid and trans-cinnamic acid was a gradient of solvent A (H2O containing 1.3% (v/v) acetic acid) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile) applied as following time procedure: 0–20 min, 10–100% B (linear); 20–20.5 min, 100–10% B (linear); 20.5–30 min, 10% B (isocratic); the flow rate was set at 1.0 mL min−1 and the injection volume was 10 μL. The column was maintained at 35 °C, and the eluted compounds were monitored at 290 nm for both p-coumaric acid and trans-cinnamic acid. While acetaminophen was analyzed with a gradient of solvent A (H2O containing 0.05% (v/v) phosphoric acid) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile) applied as following time procedure: 0–10 min, 10–50% B (linear); 10–15 min, 50% B (isocratic); 15–17 min, 50–10% B (linear); 17–20 min, 10% B (isocratic); the flow rate was 1.0 mL min−1 and the injection volume was 10 μL. The column was maintained at 30 °C, and the eluted compounds were monitored at 254 nm. The concentration of chemicals were quantified by fitting the peak area with a standard curve (R2 > 0.999) of the corresponding standard.

Statistical analysis

During the batch cultivation, at least three clones of each recombinant strain were performed for the measurement. After each measurement, the average value and the standard error (SE) of at least three independent batches of each strain were calculated and used for analysis. The mean and the SE were calculated using Microsoft® Excel® 2019 and the final experimental data were represented as mean ± SE. To test whether the differences among different recombinant strains were significant, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS Statistics 19.0 with Duncan’s new multiple range test (P < 0.05). The exact P value was calculated by two-sided t-test using Microsoft® Excel® 2019.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 31600074) to Y.L. (Yikui Li), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 31770387) to R.W., the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (NO. BK20160599) to Y.L. (Yikui Li), and the Open Fund of Jiangsu Key Laboratory for the Research and Utilization of Plant Resources (NO. JSPKLB202201) to R.W. We thank Prof. Qingsheng Qi at Shandong University for his comments on this manuscript. We thank Prof. Qun Wan and Prof. Wen-Biao Shen at Nanjing Agricultural University, and Dr. Zheng-Xiong Zhou and Dr. Song-Feng Wang at Institute of Botany, Jiangsu Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences for their suggestions.

Author contributions

Y.L. (Yikui Li) and R.W. generated the idea. Y.L. (Yikui Li), J.L., W.K.C. and R.W. designed the project. J.L. and Y.L. (Yang Li) performed experiments. Y.L. (Yikui Li), J.L., W.K.C., B.X. and R.W. analyzed the data. Y.L. (Yikui Li), W.K.C., S.X., L.L. and R.W. wrote the manuscript with editing from all authors. R.W. supervised the research.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD056539. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yikui Li, Jie Li.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54259-1.

References

- 1.Lewis, J. C., Coelho, P. S. & Arnold, F. H. Enzymatic functionalization of carbon-hydrogen bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev.40, 2003–2021 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortiz de Montellano, P. R. Substrate oxidation by cytochrome P450 enzymes. In Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry (eds Ortiz de Montellano, P. R.) 111–176 (Springer, Cham, 2015).

- 3.Tang, M. C., Zou, Y., Watanabe, K., Walsh, C. T. & Tang, Y. Oxidative cyclization in natural product biosynthesis. Chem. Rev.117, 5226–5333 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pateraki, I., Heskes, A. M. & Hamberger, B. Cytochromes P450 for terpene functionalisation and metabolic engineering. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol.148, 107–139 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gesell, A. et al. CYP719B1 is salutaridine synthase, the C-C phenol-coupling enzyme of morphine biosynthesis in opium poppy. J. Biol. Chem.284, 24432–24442 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frick, S., Kramell, R. & Kutchan, T. M. Metabolic engineering with a morphine biosynthetic P450 in opium poppy surpasses breeding. Metab. Eng.9, 169–176 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winzer, T. et al. Morphinan biosynthesis in opium poppy requires a P450-oxidoreductase fusion protein. Science349, 309–312 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrow, S. C., Hagel, J. M., Beaudoin, G. A., Burns, D. C. & Facchini, P. J. Stereochemical inversion of (S)-reticuline by a cytochrome P450 fusion in opium poppy. Nat. Chem. Biol.11, 728–732 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roiban, G.-D. & Reetz, M. T. Expanding the toolbox of organic chemists: directed evolution of P450 monooxygenases as catalysts in regio- and stereoselective oxidative hydroxylation. Chem. Commun.51, 2208–2224 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, R. K. et al. Enzymatic assembly of carbon-carbon bonds via iron-catalysed sp3 C-H functionalization. Nature565, 67–72 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galanie, S., Thodey, K., Trenchard, I. J., Filsinger Interrante, M. & Smolke, C. D. Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science349, 1095–1100 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biggs, B. W. et al. Overcoming heterologous protein interdependency to optimize P450-mediated Taxol precursor synthesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA113, 3209–3214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paddon, C. J. et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature496, 528–532 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajikumar, P. K. et al. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science330, 70–74 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang, M. C., Eachus, R. A., Trieu, W., Ro, D. K. & Keasling, J. D. Engineering Escherichia coli for production of functionalized terpenoids using plant P450s. Nat. Chem. Biol.3, 274–277 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ro, D. K. et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature440, 940–943 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo, X. et al. Complete biosynthesis of cannabinoids and their unnatural analogues in yeast. Nature567, 123–126 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hannemann, F., Bichet, A., Ewen, K. M. & Bernhardt, R. Cytochrome P450 systems–biological variations of electron transport chains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1770, 330–344 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanukoglu, I. Electron transfer proteins of cytochrome P450 systems. In Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology (eds Bittar, E. E.) 29–56 (Elsevier, 1996).

- 20.Laursen, T., Møller, B. L. & Bassard, J.-E. Plasticity of specialized metabolism as mediated by dynamic metabolons. Trends Plant Sci.20, 20–32 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennewein, S. et al. Coexpression in yeast of Taxus cytochrome P450 reductase with cytochrome P450 oxygenases involved in Taxol biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng.89, 588–598 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eberle, D., Ullmann, P., Werck-Reichhart, D. & Petersen, M. cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of CYP98A14 and NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase from Coleus blumei involved in rosmarinic acid biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol.69, 239–253 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducassou, L. et al. Expression in yeast, new substrates, and construction of a first 3D model of human orphan cytochrome P450 2U1: interpretation of substrate hydroxylation regioselectivity from docking studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1850, 1426–1437 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard, E. & Koffas, M. A. Engineering of artificial plant cytochrome P450 enzymes for synthesis of isoflavones by Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.73, 7246–7251 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narhi, L. O. & Fulco, A. J. Characterization of a catalytically self-sufficient 119,000-dalton cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase induced by barbiturates in Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem.261, 7160–7169 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croteau, R., Ketchum, R. E., Long, R. M., Kaspera, R. & Wildung, M. R. Taxol biosynthesis and molecular genetics. Phytochem. Rev.5, 75–97 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehlting, J., Hamberger, B., Million-Rousseau, R. & Werck-Reichhart, D. Cytochromes P450 in phenolic metabolism. Phytochem. Rev.5, 239–270 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, Y. et al. De novo biosynthesis of p-coumaric acid in E. coli with a trans-cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase from the Amaryllidaceae plant Lycoris aurea. Molecules23, 3185 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narhi, L. O. & Fulco, A. J. Identification and characterization of two functional domains in cytochrome P-450BM-3, a catalytically self-sufficient monooxygenase induced by barbiturates in Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem.262, 6683–6690 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zakeri, B. et al. Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA109, E690–E697 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunkley, T. P. et al. Mapping the Arabidopsis organelle proteome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA103, 6518–6523 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veggiani, G. et al. Programmable polyproteams built using twin peptide superglues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA113, 1202–1207 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson, J. R., Coon, M. J. & Porter, T. D. Purification and properties of a shortened form of cytochrome P-450 2E1: deletion of the NH2-terminal membrane-insertion signal peptide does not alter the catalytic activities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA88, 9141–9145 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott, E. E. et al. The role of protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions on P450 function. Drug Metab. Dispos.44, 576–590 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estabrook, R. W., Shet, M. S., Fisher, C. W., Jenkins, C. M. & Waterman, M. R. The interaction of NADPH-P450 reductase with P450: an electrochemical study of the role of the flavin mononucleotide-binding domain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.333, 308–315 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Im, S. C. & Waskell, L. The interaction of microsomal cytochrome P450 2B4 with its redox partners, cytochrome P450 reductase and cytochrome b5. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.507, 144–153 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnaba, C., Taylor, E. & Brozik, J. A. Dissociation constants of cytochrome P450 2C9/cytochrome P450 reductase complexes in a lipid bilayer membrane depend on NADPH: a single-protein tracking study. J. Am. Chem. Soc.139, 17923–17934 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes, H. J., Arlotto, M. P. & Waterman, M. R. Expression and enzymatic activity of recombinant cytochrome P450 17 alpha-hydroxylase in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA88, 5597–5601 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillam, E. M., Baba, T., Kim, B. R., Ohmori, S. & Guengerich, F. P. Expression of modified human cytochrome P450 3A4 in Escherichia coli and purification and reconstitution of the enzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.305, 123–131 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dueber, J. E. et al. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat. Biotechnol.27, 753–759 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iyanagi, T. Molecular mechanism of phase I and phase II drug-metabolizing enzymes: implications for detoxification. Int. Rev. Cytol.260, 35–112 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turpeinen, M. et al. A predominate role of CYP1A2 for the metabolism of nabumetone to the active metabolite, 6-methoxy-2-naphthylacetic acid, in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos.37, 1017–1024 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rendic, S. Summary of information on human CYP enzymes: human P450 metabolism data. Drug Metab. Rev.34, 83–448 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweetlove, L. J. & Fernie, A. R. The role of dynamic enzyme assemblies and substrate channelling in metabolic regulation. Nat. Commun.9, 2136 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han, J. D. et al. Evidence for dynamically organized modularity in the yeast protein-protein interaction network. Nature430, 88–93 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Estabrook, R. W., Franklin, M. R., Cohen, B., Shigamatzu, A. & Hildebrandt, A. G. Biochemical and genetic factors influencing drug metabolism. Influence of hepatic microsomal mixed function oxidation reactions on cellular metabolic control. Metabolism20, 187–199 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson, J. A., Ebel, R. E., O’Keeffe, D. H., Matsubara, T. & Estabrook, R. W. Temperature dependence of cytochrome P-450 reduction. A model for NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase:cytochrome P-450 interaction. J. Biol. Chem.251, 4010–4016 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shephard, E. A., Phillips, I. R., Bayney, R. M., Pike, S. F. & Rabin, B. R. Quantification of NADPH:cytochrome P-450 reductase in liver microsomes by a specific radioimmunoassay technique. Biochem. J.211, 333–340 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miwa, G. T. & Lu, A. Y. The association of cytochrome P-450 and NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase in phospholipid membranes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.234, 161–166 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laursen, T. et al. Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum. Science354, 890–893 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zelasko, S., Palaria, A. & Das, A. Optimizations to achieve high-level expression of cytochrome P450 proteins using Escherichia coli expression systems. Protein Expr. Purif.92, 77–87 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park, S. Y., Eun, H., Lee, M. H. & Lee, S. Y. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli with electron channelling for the production of natural products. Nat. Catal.5, 726–737 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nooren, I. M. & Thornton, J. M. Diversity of protein-protein interactions. EMBO J.22, 3486–3492 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dill, K. A. Dominant forces in protein folding. Biochemistry29, 7133–7155 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newberry, R. W. & Raines, R. T. Secondary forces in protein folding. ACS Chem. Biol.14, 1677–1686 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roel-Touris, J., Jimenez-Garcia, B. & Bonvin, A. Integrative modeling of membrane-associated protein assemblies. Nat. Commun.11, 6210 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birch, J. et al. The fine art of integral membrane protein crystallisation. Methods147, 150–162 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chambers, M. C. et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol.30, 918–920 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Towbin, H., Staehelin, T. & Gordon, J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA76, 4350–4354 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burnette, W. N. “Western blotting”: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal. Biochem.112, 195–203 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alegria-Schaffer, A. Western blotting using chemiluminescent substrates. Methods Enzymol.541, 251–259 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD056539. Source data are provided with this paper.