Abstract

The gut is traditionally recognized as the central organ for the digestion and absorption of nutrients, however, it also functions as a significant endocrine organ, secreting a variety of hormones such as glucagon-like peptide 1, serotonin, somatostatin, and glucocorticoids. These gut hormones, produced by specialized intestinal epithelial cells, are crucial not only for digestive processes but also for the regulation of a wide range of physiological functions, including appetite, metabolism, and immune responses. While gut hormones can exert systemic effects, they also play a pivotal role in maintaining local homeostasis within the gut. This review discusses the role of the gut as an endocrine organ, emphasizing the stimuli, the newly discovered functions, and the clinical significance of gut-secreted hormones. Deciphering the emerging role of gut hormones will lead to a better understanding of gut homeostasis, innovative treatments for disorders in the gut, as well as systemic diseases.

Keywords: Enteroendocrine cells, Gut, Gut hormones, Intestinal homeostasis, Intestinal epithelial cells

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of secretin by Bayliss and Starling in 1902 marked a pivotal moment in endocrinology, introducing the concept of hormones and establishing the gastrointestinal tract as an endocrine organ (Bayliss and Starling, 1902). This seminal finding paved the way for the identification and characterization of numerous gut hormones. Since then, more than 30 hormones have been reported to be produced from the gut, each playing crucial roles in digestion, absorption, metabolism, and homeostasis (Rehfeld, 2014).

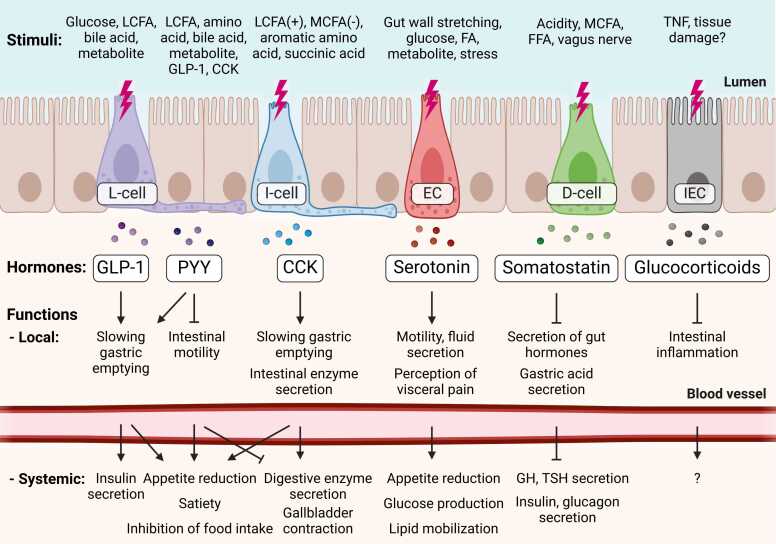

The gastrointestinal epithelium, long recognized for its roles in digestion, absorption, and barrier function, has also emerged as a source of gut hormones (Gribble and Reimann, 2019). This dynamic cellular interface comprises various specialized enteroendocrine cells (EECs) dispersed among the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), secreting a diverse array of hormones in response to luminal and neuronal stimuli (Bany Bakar et al., 2023). Enterochromaffin cells (ECs), the most abundant EECs, primarily secrete serotonin (5-HT), which not only regulates motility, secretion, and visceral sensation, but also influences central nervous system (CNS) functions (Bayrer et al., 2023). l-cells, predominantly found in the ileum and colon, produce glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which are key players in glucose-dependent insulin secretion, satiety, gastric emptying, and gastric motility and secretion, respectively (Ahren, 2011, Habib et al., 2012). K-cells, located in the duodenum and jejunum, secrete glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), which enhances insulin secretion and regulates lipid metabolism (Holst et al., 2021). I-cells in the duodenum and jejunum release cholecystokinin (CCK), stimulating pancreatic enzyme secretion, gallbladder contraction, and inducing satiety (Barakat et al., 2024). S-cells, scattered throughout the small intestine, produce secretin, which regulates pancreatic bicarbonate secretion (Modvig et al., 2020). Additionally, d-cells secrete somatostatin, a universal inhibitor of other endocrine and exocrine secretions throughout the gastrointestinal tract (Shamsi et al., 2021). More recently, IECs themselves have been shown to synthesize and produce glucocorticoids that regulate local immune responses, adding another layer of complexity to the endocrine function of the gut (Ahmed et al., 2019a). This diverse array of EECs and their hormone products forms an intricate network that fine-tunes digestive processes, modulates appetite, and influences systemic metabolism, underscoring the gut as a major endocrine organ.

Recent advances in molecular biology and high-throughput sequencing technologies have significantly expanded our understanding of gut hormones and their functions. These developments have revealed the remarkable complexity of IECs and their interactions with the enteric nervous system (ENS), immune cells, and the gut microbiome (Haber et al., 2017). This review aims to summarize the latest updates on the biogenesis, physiological functions, regulatory networks, and potential therapeutic implications of 6 key intestinal hormones: GLP-1, PYY, CCK, serotonin, somatostatin, and glucocorticoids.

MAIN TEXT

GLP-1: A Master Regulator of Metabolism With Significant Drug Potential

GLP-1 is synthesized and secreted from enteroendocrine l-cells, primarily located in the distal ileum and colon (Arora et al., 2021) (Fig. 1). The ingestion of nutrients, especially carbohydrates and fats, serves as the primary trigger for GLP-1 release (Gribble and Reimann, 2016) (Table 1). Glucose via the sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1, as well as long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) via free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFAR1) and FFAR4, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) via FFAR3 and FFAR2 are responsible for the stimulation of l-cells (Bodnaruc et al., 2016). This process can be further enhanced by other hormones, bile acids, and neural signals from the vagus nerve (Rocca and Brubaker, 1999). For example, feedback mechanisms involving the autonomic nervous system and other gut hormones, such as CCK, GIP, and serotonin, regulate the GLP-1 secretion to align with the metabolic demand (Hansen and Holst, 2002).

Fig. 1.

Summary of stimuli and functions of gut hormones. Illustration of representative stimuli and functions (local and systemic) of 6 gut hormones. The position of each cell type is arbitrary and does not reflect anatomical location. LCFA, long-chain fatty acid; MCFA, medium-chain fatty acid; FFA, free fatty acid; EC, enterochromaffin cell; IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; PYY, peptide YY; CCK, cholecystokinin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor, GH, growth hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone. For more detailed information, refer to Table 1. Created with BioRender.com.

Table 1.

Comparison of 6 gut hormones by stimuli, secretory cells, biogenic factors, and functions

| Stimuli | Secretory cells | Biogenic factors (TF/enzyme) | Function (local) | Function (systemic) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 |

|

L-cell of EEC in distal ileum, proximal colon | PDX1 NEUROD1/prohormone convertase 1/3 |

|

(Brain) Reducing appetite, satiety, and inhibition of food intake (Pancreas) Enhancing insulin secretion |

| PYY |

|

L-cell of EEC in ileum, colon | Prohormone convertase 1/3 |

|

(Brain) Reducing appetite, satiety, and inhibition of food intake (Pancreas) Inhibition of pancreatic enzyme secretion, enhancing insulin secretion (Gallbladder) Inhibiting gallbladder contraction (Adriaenssens et al., 2018) |

| CCK |

|

I-cell of EEC in duodenum, jejunum | Prohormone convertase 1/3 |

|

(Brain) Reducing appetite, satiety, and acute suppression of food intake (Pancreas) Promoting pancreatic enzyme secretion (Gallbladder) Stimulating gallbladder contraction |

| Serotonin |

|

ECs in duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon | LMX1A (Gross et al., 2016)/TPH1, and AADC |

|

(Brain) Reducing appetite (Liver) Increasing glucose production (Adipose tissue) Increasing lipid mobilization |

| Somatostatin |

|

D-cell of EEC in gastric fundus, antrum, duodenum, and jejunum | PDX1/prohormone convertase 1 |

|

(Brain) Inhibition of GH and TSH secretion (Nerve) Inhibition of neurotransmitter release (Pancreas) Inhibition of insulin and glucagon secretion (Rorsman and Huising, 2018) |

| Glucocorticoids |

|

IECs (intestinal crypt cells) in ileum, colon | LRH-1/CYP11A1, CYP11B1, and 11β-HSD1 |

|

Unknown |

GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; LCFAs, long-chain fatty acids; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; CCK, cholecystokinin; GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; IL, interleukin; EEC, enteroendocrine cell; TF, transcription factor; PDX-1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; NEUROD1, neurogenic differentiation 1; PYY, peptide YY; MCFAs, medium-chain fatty acids; ECs, enterochromaffin cells; GH, growth hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; LRH-1, liver receptor homolog-1; CYP, cytochrome P450 family; 11β-HSD1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1.

Of note, GLP-1 levels are elevated in germ-free mice, suggesting that microbiota generally suppress basal GLP-1 to maintain intestinal transit (Wichmann et al., 2013). However, a recent study demonstrated that P9, a specific protein derived from Akkermansia muciniphila, can significantly induce GLP-1 secretion in a manner distinct from SCFAs (Yoon et al., 2021). Moreover, luminal lipopolysaccharides or interleukin-6 (IL-6) can enhance GLP-1 secretion following gut barrier injury (Ellingsgaard et al., 2011, Lebrun et al., 2017), suggesting a critical role for GLP-1 in maintaining gut homeostasis. As l-cells act as pathogen sensors, proinflammatory and microbial signals may also trigger GLP-1 secretion (Lebrun et al., 2017). Therefore, the secretion of GLP-1 is coordinated in response to food intake and disruption of microbial homeostasis.

The production of GLP-1 is tightly regulated at the molecular level. Key transcription factors, including pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) and neurogenic differentiation 1 (NEUROD1), play crucial roles in the expression of the proglucagon gene, which encodes GLP-1 (MacDonald et al., 2002). Once the proglucagon precursor is produced, it is processed by the enzyme prohormone convertase 1/3 to generate GLP-1 (Holst, 2022, Mojsov et al., 1986). Notably, GLP-2 is also derived from the same proglucagon but primarily regulates IEC growth and repair, which are crucial for proper digestion and nutrient absorption (Drucker and Yusta, 2014).

GLP-1 has multiple functions. It enhances insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, thereby playing a crucial role in glucose homeostasis (Muller et al., 2019). Additionally, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying, promotes satiety (Kim et al., 2024), and reduces food intake by acting on the CNS, particularly the hypothalamus (Zhang et al., 2022). This multifaceted role makes GLP-1 an essential hormone for regulating glucose metabolism and energy balance. Of note, a recent study suggests that GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1Rs) on gut intraepithelial lymphocytes can inhibit proximal T-cell receptor signaling through a protein kinase A–dependent mechanism (Wong et al., 2022). This highlights a broader role for GLP-1 beyond glucose regulation, demonstrating its capacity to regulate both systemic and local inflammation by regulating the function of T cells within the gut.

Given the impact of GLP-1 on metabolism, GLP-1 analogs (also known as GLP-1 receptor agonists, GLP-1RAs) have been used as potent treatments for type 2 diabetes and obesity (Gallwitz, 2022, Knudsen and Lau, 2019, Nachawi et al., 2022). GLP-1RAs reduce blood sugar and food intake by mimicking GLP-1 activation through G-protein-coupled receptor (GPR) signaling (Gao et al., 2024). One of the successful drugs is Wegovy (semaglutide), which mimics GLP-1, promoting weight loss by reducing appetite and increasing satiety (Senior, 2023). Beyond the direct use of GLP-1 analogs, there is potential for targeting the enzymes or cytokines that regulate GLP-1 as therapeutic strategies. For example, the rapid degradation of GLP-1 by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 in the bloodstream limits its action, providing a mechanism to finely tune its physiological effects (Deacon, 2019).

PYY: The Link Between Food Intake, Digestion, and Perception

Similar to GLP-1, PYY is synthesized and secreted by enteroendocrine l-cells located in the ileum and colon (Ekblad and Sundler, 2002) (Fig. 1). The synthesis of PYY begins with the production of the precursor protein prepro-PYY, which is then processed by the enzyme prohormone convertase 1/3 into the active forms PYY1-36 and PYY3-36 (Medeiros and Turner, 1994) (Table 1). Among these, PYY3-36 is the most biologically active and plays a crucial role in regulating appetite and energy balance (Batterham et al., 2002).

The secretion of PYY is closely linked to food intake, particularly the ingestion of fats and proteins (Adrian et al., 1985, Batterham et al., 2006). The presence of LCFAs in the lumen is especially potent in triggering PYY release via GPR40 and GPR120 (Dirksen et al., 2019). In addition to being stimulated by nutrients, PYY levels are also influenced by the autonomic nervous system and other gut hormones like GLP-1 and CCK, which often act synergistically to promote satiety (Williams et al., 2016, Wu et al., 2013). Furthermore, microbial metabolites such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate increase the expression of PYY via histone deacetylase (Larraufie et al., 2018), while fermentation products drive the expansion of the PYY-producing l-cells (Brooks et al., 2017).

Functionally, PYY helps slow gastric emptying and enhances intestinal motility, which allows for better nutrient absorption and prolongs the sensation of satiety (Duca et al., 2021, McCauley et al., 2020). In addition, PYY, which is released in response to fats, is crucial for the ileal brake. This mechanism slows intestinal transit when undigested fats are present in the distal small intestine (Lin et al., 1996). Systemically, PYY acts on the hypothalamus in the brain to reduce appetite, contributing to the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis (Batterham et al., 2006). This action on the brain is particularly important, as PYY3-36 binds to the Y2 receptors in the hypothalamus, inhibiting the release of neuropeptide Y, a potent stimulator of appetite, thus reducing food intake (Batterham et al., 2002, Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2005).

CCK: Regulation of Digestion and Appetite

CCK is primarily synthesized and secreted by enteroendocrine I-cells, which are located in the duodenum and jejunum (Bany Bakar et al., 2023) (Fig. 1). The secretion of CCK is stimulated by the presence of partially digested fats and proteins in the small intestine. For example, LCFAs induce the secretion of CCK via GPR40, whereas medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) inhibit the secretion of CCK via GPR120 (Liou et al., 2011, Murata et al., 2021) (Table 1). Aromatic amino acids, including phenylalanine and tryptophan, stimulate the release of CCK via the calcium-sensing receptor (Wang et al., 2011). In addition to nutrients, succinic acid can induce CCK release from EEC cells in a dose-dependent manner (Egberts et al., 2020). Also, microbial-derived products, lipopolysaccharides through TLR9, can regulate the secretion of CCK (Barakat et al., 2024, Daly et al., 2020).

CCK exerts a variety of effects that are essential for digestion and the regulation of food intake. One of its primary roles is to stimulate the gallbladder to contract and release bile into the small intestine, which is crucial for the emulsification and absorption of dietary fats (Gribble and Reimann, 2019). CCK also acts on the pancreas, promoting the secretion of digestive enzymes that further break down proteins, fats, and carbohydrates in the small intestine (Moran and Kinzig, 2004). These actions facilitate the efficient digestion and absorption of nutrients. Besides its local bowel functions, CCK also plays an important systemic role in regulating satiety. It acts on the vagus nerve, sending signals to the brain to induce feelings of fullness and reduce food intake (Gibbs et al., 1973). Moreover, CCK can regulate CD4 T-cell functions and inhibit inflammatory responses (Zhang et al., 2014).

Serotonin: A Multifaceted Hormone Produced Mainly in the Gut

Serotonin, a monoamine neurotransmitter, is predominantly synthesized and secreted in the gut, where more than 90% of the serotonin found in the entire organism is produced (Martin et al., 2018). This process begins with the conversion of the amino acid tryptophan into serotonin, primarily within EC cells, which are specialized EECs dispersed throughout the small intestine and colon (Bellono et al., 2017) (Fig. 1). The synthesis of serotonin in EC cells involves 2 key enzymes. First, tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) converts tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan (Walther and Bader, 2003) (Table 1). TPH1 is the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway and is crucial for the regulation of serotonin production in the gut (Walther and Bader, 2003). Then, aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) further converts 5-hydroxytryptophan into serotonin (Del Colle et al., 2020). Interestingly, AADC can also be derived from Firmicutes species from the microbiota, resulting in the stimulation of colonic serotonin production (Sugiyama et al., 2022).

The secretion of serotonin is primarily triggered by mechanical (Treichel et al., 2022) and chemical (Kaelberer et al., 2018) stimuli within the gut. For example, the stretching of the gut wall due to food intake or the presence of specific nutrients like glucose and fatty acids can stimulate EC cells to release serotonin into the gut lumen and the surrounding tissue (Nozawa et al., 2009). Specifically, mechanotransduction by Piezo2 can increase intracellular calcium in EC cells, thereby inducing the secretion of serotonin and epithelial fluid (Alcaino et al., 2018). Additionally, neuronal inputs and cytokines can control serotonin release. For instance, a recent study showed that IL-33 induces serotonin secretion in EC cells, facilitating intestinal helminth clearance (Chen et al., 2021). Apart from the secretion, serotonin can also be reabsorbed by the serotonin transporter (SERT), which is present on enterocytes and helps limit its action by removing it from the gut lumen (Bertrand and Bertrand, 2010). Dysregulation of serotonin production, secretion, or reuptake can lead to various gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, where altered serotonin signaling is often implicated (Tao et al., 2022).

Serotonin acts on both local and systemic levels. Locally, it binds to serotonin receptors on enteric neurons, smooth muscle cells, and epithelial cells, influencing gut motility, secretion, and sensation (Gershon, 2013). It acts locally to promote epithelial growth, enteric neurogenesis, and activity (Bellono et al., 2017). Moreover, serotonin is a key regulator of peristalsis, the coordinated contraction and relaxation of gut muscles that propel food through the digestive tract (Terry and Margolis, 2017). Recent studies have revealed that the microbiota can indirectly activate colonic motility by providing SCFAs to EC cells, which leads to enhanced expression of TPH1 and serotonin synthesis (Kwon et al., 2019, Singhal et al., 2019, Spohn and Mawe, 2017). It also stimulates the secretion of digestive fluids and influences the sensation of nausea and pain (Bayrer et al., 2023). In contrast, when serotonin enters the bloodstream, it systemically acts on distant organs, including the heart, liver, and blood vessels (Berger et al., 2009). Inhibition of serotonin synthesis in Tph1-deficient mice was linked to an increased metabolic rate and enhanced brown adipose tissue activity, highlighting its systemic effect (Crane et al., 2015).

Clinically, increased serotonin levels have been associated with the severity of symptoms and clinical outcomes in patients with colitis and visceral pain (Kim et al., 2013, Koopman et al., 2021, Shajib et al., 2013). Thus, targeted therapies against serotonin might be used to treat intestinal inflammation, chronic nausea, and visceral pain disorders (Mawe and Hoffman, 2013).

Somatostatin: A Unique Inhibitory Regulator

Somatostatin is a key regulatory hormone in the gastrointestinal system, synthesized and secreted by d-cells, which are specialized EECs found particularly in the stomach, small intestine, as well as delta cells in pancreas (Posovszky and Wabitsch, 2015) (Fig. 1). Somatostatin is specialized in inhibiting the secretion of various other hormones and enzymes, thereby acting as a suppressor of digestive processes (Lloyd, 1994).

The secretion of somatostatin is stimulated by several factors, including increased acidity in the stomach, the presence of nutrients in the gut, and neurotransmitters (Goo et al., 2010, Lucey, 1986) (Table 1). For instance, after a meal, the rise in gastric acidity and the presence of partially digested food in the stomach and small intestine prompt d-cells to release somatostatin (Bany Bakar et al., 2023). d-cells are able to sense various nutrients via a range of receptors, specifically GPR84, which is able to sense MCFAs. Then, the activation of 5 G-protein-coupled somatostatin receptor subtypes (SSTR1-5) enhances somatostatin secretion (Li et al., 2021).

The somatostatin secretion is tightly regulated to ensure that digestive processes are neither overly stimulated nor excessively inhibited. As the pH levels in the stomach return to normal and nutrient absorption in the intestine progresses, the stimulus for somatostatin release decreases, allowing other digestive hormones to resume their activity. This negative feedback loop is essential for maintaining a balanced and efficient digestion (Rorsman and Huising, 2018). Moreover, somatostatin release from the intestine is controlled by the vagus nerve and various local ENS neurotransmitters (Lewin et al., 2016).

Somatostatin acts locally in a paracrine manner as well as systemically through the bloodstream. In the intestines, somatostatin reduces the secretion of digestive enzymes and slows down intestinal motility (Shamsi et al., 2021). In the stomach, it inhibits the release of gastrin from G-cells, thereby reducing gastric acid secretion and slowing down gastric emptying (Egerod et al., 2015). This helps protect the stomach lining from excessive acidity and regulates the digestive process. In the pancreas, somatostatin inhibits the release of insulin and glucagon through SSTR2 and SSTR5, respectively, playing a role in glucose homeostasis (Jepsen et al., 2019, Orgaard and Holst, 2017). In addition to gut hormones, somatostatin can inhibit the secretion of growth hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone from the pituitary gland, as well as regulate neurotransmitter release in the CNS (Marciniak and Brasun, 2017).

Glucocorticoids: Inhibition of Intestinal Inflammation by Local Stress Hormones

Glucocorticoids, commonly known as stress hormones, are primarily synthesized in the adrenal cortex (Nicolaides et al., 2017). However, recent studies increasingly suggest that the gut can also produce these hormones locally (Ahmed et al., 2019a, Cima et al., 2004, Noti et al., 2010b). Interestingly, IECs are capable of expressing a critical transcription factor, NR5A2 (also known as liver receptor homolog-1, LRH-1), which in turn drives the expression of key enzymes necessary for glucocorticoid synthesis, including cytochrome P450 family (CYP) 11A1 and CYP11B1 (Mueller et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). It was demonstrated that IECs exhibit confined expression of key steroidogenic enzymes, specifically CYP11A1 and CYP11B1, as well as NR5A2 (Cima et al., 2004). In line with this, the level of intestinal glucocorticoids can be regulated by the small heterodimer partner (SHP) that acts as a transcriptional repressor of NR5A2 and downregulates the expression of steroidogenic enzymes (Benod et al., 2013).

While systemic glucocorticoids are produced in response to various stressors or adrenocorticotropic hormone via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, the stimuli for locally secreted stress hormones in the intestine remain poorly characterized. So far, colitis-induced tumor necrosis factor-⍺ and antibiotic-induced microbiome depletion have been shown to upregulate the steroidogenic enzymes, implying that perturbations of gut homeostasis due to inflammation or dysbiosis might be responsible for the local production of glucocorticoids in the gut (Mukherji et al., 2013, Noti et al., 2010a). Thus, current understanding suggests that local synthesis in the gut is triggered by inflammation or stress, though the precise mechanisms are yet to be determined (Slominski et al., 2020). In addition to be directly synthesized, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 can convert inactive cortisone or 11-dehydrocorticosterone into active cortisol or corticosterone, increasing local glucocorticoid levels, while 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 reverses this process, reducing glucocorticoid levels (Chapman et al., 2013, Taves et al., 2023) (Table 1).

Local glucocorticoids play a crucial role in maintaining gut homeostasis by mitigating inflammation, protecting epithelial cells, and ensuring the integrity of the gut barrier. It is achieved by modulating immune responses, facilitating epithelial cell survival, and promoting cellular regeneration (Atanasov et al., 2008). Unlike other gut hormones, the systemic effects of local glucocorticoids remain unknown and require further investigation.

Given the importance of LRH-1 as a regulator of local glucocorticoid synthesis, targeting LRH-1 could be a promising therapeutic strategy for alleviating intestinal inflammation (Ahmed et al., 2019b, Ghosh et al., 2024, Landskron et al., 2022). By modulating its transcriptional activity, it may be possible to enhance local glucocorticoid synthesis, thereby improving outcomes of colitis or inflammatory bowel disease.

DISCUSSION

The gut is unique among organs due to its complex interactions with the microbiome and its extensive network of neurons, known as the ENS. Its nickname, “the second brain,” indicates that the gut can perform various tasks autonomously (Schneider et al., 2019). The gut independently manages digestion, absorption, defense, and even influences mood and systemic metabolism in a well-coordinated fashion. This feature may, in part, be attributed to its ability to communicate with diverse cell types within the tissue, including epithelial cells, immune cells, and neurons. In this regard, gut hormones can act as key mediators between those intestinal cells, playing indispensable roles in maintaining both local and systemic homeostasis.

Traditionally, endocrine hormones are released from glands, such as the thyroid, pancreas, and adrenal glands, into the bloodstream to systemically act on distant organs without directly affecting their organ of origin. For instance, insulin from the pancreas regulates blood glucose levels, while thyroid hormones control overall metabolic rate. In contrast, gut hormones can act both locally and systemically. The local effects are typically mediated through paracrine and neurocrine mechanisms, allowing for rapid and precise responses to alterations in the luminal environment. To rapidly respond to changing conditions in the gut, many gut hormones—such as CCK, which has a half-life of 1 to 2 minutes, and somatostatin, which has a half-life of 2 to 3 minutes—have very short half-lives, allowing for tight regulation of their effects and ensuring reversibility (Blake et al., 2004, Shechter et al., 2005, Wren and Bloom, 2007). When diffused into the bloodstream, these same hormones can also have systemic effects on other organs through sustained secretion or by acting on high-affinity receptors although they may also be produced in situ (Steinert et al., 2017). For systemic glucose metabolism, not only the intestine, but organs such as the liver and pancreas are stimulated by gut hormones. For appetite, satiety, and food intake, the systemic effects are primarily mediated through the CNS which receives and relays signals from gut hormones. This mechanistic connection forms one of the fundamental bases for the gut-brain axis.

More recently, gut hormones, including serotonin, CCK, and glucocorticoids, have been shown to play pivotal roles in shaping the immune system, especially immune cell differentiation and function (Cima et al., 2004, Wan et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2014). These findings underscore the intimate link between the gut hormones and immune system, further demonstrating the emerging role of gut hormones in regulating local and systemic homeostasis through the immune system. Collectively, the gut may serve as a central organ and hub for interorgan crosstalk between different organs via gut hormones as well as cytokines and exosomes. Further detailed investigations are necessary to elucidate the precise mechanisms by which the gut orchestrates interorgan communication through various signaling factors.

In addition to their effects on local and systemic variables, the gut hormones themselves can affect each other, demonstrating even more complex interactions. For instance, somatostatin inhibits the secretion of GLP-1 (Hansen et al., 2000), and CCK stimulates PYY through hydrolysis of fat (Degen et al., 2007). Also, PYY regulates the intestinal motility, secretion, and absorption, as well as visceral sensitivity via serotonin release from colonic EC cells (Kojima et al., 2015, Spohn and Mawe, 2017). Elucidating these interconnected processes can lead to a deeper understanding of disease pathogenesis and potentially enable more effective therapeutic interventions.

Since hormones generally serve as excellent soluble factors for drug development due to their high target specificity, gut hormones also hold promise in developing targeted therapeutics for various gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders. By leveraging the unique characteristics of gut hormones, one can design more precise and effective treatments, potentially improving patient outcomes and advancing the management of diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and inflammatory bowel disease. In fact, recent investigations into GLP-1 have yielded significant advancements, leading to the development and clinical implementation of GLP-1RAs for obesity and beyond (Drucker, 2024). Likewise, efforts to unravel the enteroendocrine system will open new avenues for innovative therapeutic strategies in the future (Gribble and Reimann, 2019).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.L. supervised and conceptualized the scope of the review. H.C. conducted the literature search. H.C. and J.L. prepared the figure and wrote the paper.

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the New Faculty Startup Fund (550-20230061), the Research Institute for Veterinary Science, Seoul National University, National Research Foundation (NRF), Ministry of Science, Information and Communication Technology (ICT), and Future Planning of Korea (RS-2024-00335057 and RS-2024-00398705).

ORCID

Hyeryeong Cho: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8287-7884

Jaechul Lim: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6075-2656

REFERENCES

- Adriaenssens A.E., Reimann F., Gribble F.M. Distribution and stimulus secretion coupling of enteroendocrine cells along the intestinal tract. Compr Physiol. 2018;8:1603–1638. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian T.E., Long R.G., Fuessl H.S., Bloom S.R. Plasma peptide YY (PYY) in dumping syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1985;30:1145–1148. doi: 10.1007/BF01314048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A., Schmidt C., Brunner T. Extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis in the intestinal mucosa: between immune homeostasis and immune escape. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1438. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A., Schwaderer J., Hantusch A., Kolho K.L., Brunner T. Intestinal glucocorticoid synthesis enzymes in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Genes Immun. 2019;20:566–576. doi: 10.1038/s41435-019-0056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahren B. The future of incretin-based therapy: novel avenues—novel targets. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011;13:158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaino C., Knutson K.R., Treichel A.J., Yildiz G., Strege P.R., Linden D.R., Li J.H., Leiter A.B., Szurszewski J.H., Farrugia G., et al. A population of gut epithelial enterochromaffin cells is mechanosensitive and requires Piezo2 to convert force into serotonin release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E7632–E7641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804938115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora T., Vanslette A.M., Hjorth S.A., Backhed F. Microbial regulation of enteroendocrine cells. Med. 2021;2:553–570. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasov A.G., Leiser D., Roesselet C., Noti M., Corazza N., Schoonjans K., Brunner T. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis in murine intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2008;22:4117–4125. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bany Bakar R., Reimann F., Gribble F.M. The intestine as an endocrine organ and the role of gut hormones in metabolic regulation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023;20:784–796. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00830-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat G.M., Ramadan W., Assi G., Khoury N.B.E. Satiety: a gut-brain-relationship. J. Physiol. Sci. 2024;74:11. doi: 10.1186/s12576-024-00904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham R.L., Cowley M.A., Small C.J., Herzog H., Cohen M.A., Dakin C.L., Wren A.M., Brynes A.E., Low M.J., Ghatei M.A., et al. Gut hormone PYY(3-36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature. 2002;418:650–654. doi: 10.1038/nature00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham R.L., Heffron H., Kapoor S., Chivers J.E., Chandarana K., Herzog H., Le Roux C.W., Thomas E.L., Bell J.D., Withers D.J. Critical role for peptide YY in protein-mediated satiation and body-weight regulation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss W.M., Starling E.H. The mechanism of pancreatic secretion. J. Physiol. 1902;28:325–353. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1902.sp000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayrer J.R., Castro J., Venkataraman A., Touhara K.K., Rossen N.D., Morrie R.D., Maddern J., Hendry A., Braverman K.N., Garcia-Caraballo S., et al. Gut enterochromaffin cells drive visceral pain and anxiety. Nature. 2023;616:137–142. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05829-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayrer J.R., Wang H., Nattiv R., Suzawa M., Escusa H.S., Fletterick R.J., Klein O.D., Moore D.D., Ingraham H.A. LRH-1 mitigates intestinal inflammatory disease by maintaining epithelial homeostasis and cell survival. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4055. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06137-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellono N.W., Bayrer J.R., Leitch D.B., Castro J., Zhang C., O'Donnell T.A., Brierley S.M., Ingraham H.A., Julius D. Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways. Cell. 2017;170:185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.034. e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benod C., Carlsson J., Uthayaruban R., Hwang P., Irwin J.J., Doak A.K., Shoichet B.K., Sablin E.P., Fletterick R.J. Structure-based discovery of antagonists of nuclear receptor LRH-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:19830–19844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M., Gray J.A., Roth B.L. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009;60:355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand P.P., Bertrand R.L. Serotonin release and uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. Auton. Neurosci. 2010;153:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake A.D., Badway A.C., Strowski M.Z. Delineating somatostatin's neuronal actions. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 2004;3:153–160. doi: 10.2174/1568007043482534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnaruc A.M., Prud'homme D., Blanchet R., Giroux I. Nutritional modulation of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion: a review. Nutr. Metab. 2016;13:92. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks L., Viardot A., Tsakmaki A., Stolarczyk E., Howard J.K., Cani P.D., Everard A., Sleeth M.L., Psichas A., Anastasovskaj J., et al. Fermentable carbohydrate stimulates FFAR2-dependent colonic PYY cell expansion to increase satiety. Mol. Metab. 2017;6:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman K., Holmes M., Seckl J. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: intracellular gate-keepers of tissue glucocorticoid action. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:1139–1206. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Luo J., Li J., Kim G., Stewart A., Urban J.F., Jr., Huang Y., Chen S., Wu L.G., Chesler A., et al. Interleukin-33 promotes serotonin release from enterochromaffin cells for intestinal homeostasis. Immunity. 2021;54:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.014. e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima I., Corazza N., Dick B., Fuhrer A., Herren S., Jakob S., Ayuni E., Mueller C., Brunner T. Intestinal epithelial cells synthesize glucocorticoids and regulate T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1635–1646. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J.D., Palanivel R., Mottillo E.P., Bujak A.L., Wang H., Ford R.J., Collins A., Blumer R.M., Fullerton M.D., Yabut J.M., et al. Inhibiting peripheral serotonin synthesis reduces obesity and metabolic dysfunction by promoting brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Nat. Med. 2015;21:166–172. doi: 10.1038/nm.3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly K., Burdyga G., Al-Rammahi M., Moran A.W., Eastwood C., Shirazi-Beechey S.P. Toll-like receptor 9 expressed in proximal intestinal enteroendocrine cells detects bacteria resulting in secretion of cholecystokinin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;525:936–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon C.F. Physiology and pharmacology of DPP-4 in glucose homeostasis and the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2019;10:80. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen L., Drewe J., Piccoli F., Grani K., Oesch S., Bunea R., D'Amato M., Beglinger C. Effect of CCK-1 receptor blockade on ghrelin and PYY secretion in men. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007;292:R1391–R1399. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00734.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Colle A., Israelyan N., Gross Margolis K. Novel aspects of enteric serotonergic signaling in health and brain-gut disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2020;318:G130–G143. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00173.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen C., Graff J., Fuglsang S., Rehfeld J.F., Holst J.J., Madsen J.L. Energy intake, gastrointestinal transit, and gut hormone release in response to oral triglycerides and fatty acids in men with and without severe obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019;316:G332–G337. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00310.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker D.J. The benefits of GLP-1 drugs beyond obesity. Science. 2024;385:258–260. doi: 10.1126/science.adn4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker D.J., Yusta B. Physiology and pharmacology of the enteroendocrine hormone glucagon-like peptide-2. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014;76:561–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duca F.A., Waise T.M.Z., Peppler W.T., Lam T.K.T. The metabolic impact of small intestinal nutrient sensing. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:903. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21235-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egberts J.H., Raza G.S., Wilgus C., Teyssen S., Kiehne K., Herzig K.H. Release of cholecystokinin from rat intestinal mucosal cells and the enteroendocrine cell line STC-1 in response to maleic and succinic acid, fermentation products of alcoholic beverages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:589. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerod K.L., Engelstoft M.S., Lund M.L., Grunddal K.V., Zhao M., Barir-Jensen D., Nygaard E.B., Petersen N., Holst J.J., Schwartz T.W. Transcriptional and functional characterization of the G protein-coupled receptor repertoire of gastric somatostatin cells. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3909–3923. doi: 10.1210/EN.2015-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekblad E., Sundler F. Distribution of pancreatic polypeptide and peptide YY. Peptides. 2002;23:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsgaard H., Hauselmann I., Schuler B., Habib A.M., Baggio L.L., Meier D.T., Eppler E., Bouzakri K., Wueest S., Muller Y.D., et al. Interleukin-6 enhances insulin secretion by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from L cells and alpha cells. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallwitz B. Clinical perspectives on the use of the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide for the treatment of type-2 diabetes and obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1004044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Ryu H., Lee H., Kim Y.J., Lee J.H., Lee J. ER stress and unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling modulate GLP-1 receptor signaling in the pancreatic islets. Mol. Cells. 2024;47 doi: 10.1016/j.mocell.2023.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon M.D. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:14–21. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835bc703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghamari-Langroudi M., Colmers W.F., Cone R.D. PYY3-36 inhibits the action potential firing activity of POMC neurons of arcuate nucleus through postsynaptic Y2 receptors. Cell Metab. 2005;2:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Devereaux M.W., Liu C., Sokol R.J. LRH-1 agonist DLPC through STAT6 promotes macrophage polarization and prevents parenteral nutrition-associated cholestasis in mice. Hepatology. 2024;79:986–1004. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J., Young R.C., Smith G.P. Cholecystokinin decreases food intake in rats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1973;84:488–495. doi: 10.1037/h0034870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo T., Akiba Y., Kaunitz J.D. Mechanisms of intragastric pH sensing. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2010;12:465–470. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Reimann F. Enteroendocrine cells: chemosensors in the intestinal epithelium. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016;78:277–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Reimann F. Function and mechanisms of enteroendocrine cells and gut hormones in metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15:226–237. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S., Garofalo D.C., Balderes D.A., Mastracci T.L., Dias J.M., Perlmann T., Ericson J., Sussel L. The novel enterochromaffin marker Lmx1a regulates serotonin biosynthesis in enteroendocrine cell lineages downstream of Nkx2.2. Development. 2016;143:2616–2628. doi: 10.1242/dev.130682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber A.L., Biton M., Rogel N., Herbst R.H., Shekhar K., Smillie C., Burgin G., Delorey T.M., Howitt M.R., Katz Y., et al. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature. 2017;551:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature24489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib A.M., Richards P., Cairns L.S., Rogers G.J., Bannon C.A., Parker H.E., Morley T.C., Yeo G.S., Reimann F., Gribble F.M. Overlap of endocrine hormone expression in the mouse intestine revealed by transcriptional profiling and flow cytometry. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3054–3065. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen L., Hartmann B., Bisgaard T., Mineo H., Jorgensen P.N., Holst J.J. Somatostatin restrains the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 and -2 from isolated perfused porcine ileum. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;278:E1010–E1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen L., Holst J.J. The effects of duodenal peptides on glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from the ileum. A duodeno—ileal loop? Regul. Pept. 2002;110:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J.J. Glucagon and other proglucagon-derived peptides in the pathogenesis of obesity. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.964406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J.J., Gasbjerg L.S., Rosenkilde M.M. The role of incretins on insulin function and glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2021;162 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen S.L., Grunddal K.V., Wewer Albrechtsen N.J., Engelstoft M.S., Gabe M.B.N., Jensen E.P., Orskov C., Poulsen S.S., Rosenkilde M.M., Pedersen J., et al. Paracrine crosstalk between intestinal L- and D-cells controls secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;317:E1081–E1093. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00239.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelberer M.M., Buchanan K.L., Klein M.E., Barth B.B., Montoya M.M., Shen X., Bohorquez D.V. A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Science. 2018;361 doi: 10.1126/science.aat5236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.J., Bridle B.W., Ghia J.E., Wang H., Syed S.N., Manocha M.M., Rengasamy P., Shajib M.S., Wan Y., Hedlund P.B., et al. Targeted inhibition of serotonin type 7 (5-HT7) receptor function modulates immune responses and reduces the severity of intestinal inflammation. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4795–4804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.S., Park J.S., Hwang E., Park M.J., Shin H.Y., Lee Y.H., Kim K.M., Gautron L., Godschall E., Portillo B., et al. GLP-1 increases preingestive satiation via hypothalamic circuits in mice and humans. Science. 2024;385:438–446. doi: 10.1126/science.adj2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen L.B., Lau J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Front. Endocrinol. 2019;10:155. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S., Tohei A., Ikeda M., Anzai N. An endogenous tachykinergic NK2/NK3 receptor cascade system controlling the release of serotonin from colonic mucosa. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:830–835. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150825220524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman N., Katsavelis D., Hove A.S.T., Brul S., Jonge W.J., Seppen J. The multifaceted role of serotonin in intestinal homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:9487. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y.H., Wang H., Denou E., Ghia J.E., Rossi L., Fontes M.E., Bernier S.P., Shajib M.S., Banskota S., Collins S.M., et al. Modulation of gut microbiota composition by serotonin signaling influences intestinal immune response and susceptibility to colitis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;7:709–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landskron G., Dubois-Camacho K., Orellana-Serradell O., De la Fuente M., Parada-Venegas D., Bitran M., Diaz-Jimenez D., Tang S., Cidlowski J.A., Li X., et al. Regulation of the intestinal extra-adrenal steroidogenic pathway component LRH-1 by glucocorticoids in ulcerative colitis. Cells. 2022;11:1905. doi: 10.3390/cells11121905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larraufie P., Martin-Gallausiaux C., Lapaque N., Dore J., Gribble F.M., Reimann F., Blottiere H.M. SCFAs strongly stimulate PYY production in human enteroendocrine cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:74. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18259-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun L.J., Lenaerts K., Kiers D., Pais de Barros J.P., Le Guern N., Plesnik J., Thomas C., Bourgeois T., Dejong C.H.C., Kox M., et al. Enteroendocrine L cells sense LPS after gut barrier injury to enhance GLP-1 secretion. Cell Rep. 2017;21:1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin A.E., Vicini S., Richardson J., Dretchen K.L., Gillis R.A., Sahibzada N. Optogenetic and pharmacological evidence that somatostatin-GABA neurons are important regulators of parasympathetic outflow to the stomach. J. Physiol. 2016;594:2661–2679. doi: 10.1113/JP272069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li X., Geng C., Guo Y., Wang C. Somatostatin receptor 5 is critical for protecting intestinal barrier function in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021;535 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2021.111390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.C., Zhao X.T., Wang L., Wong H. Fat-induced ileal brake in the dog depends on peptide YY. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1491–1495. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou A.P., Lu X., Sei Y., Zhao X., Pechhold S., Carrero R.J., Raybould H.E., Wank S. The G-protein-coupled receptor GPR40 directly mediates long-chain fatty acid-induced secretion of cholecystokinin. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:903–912. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd K.C. Gut hormones in gastric function. Baillieres Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994;8:111–136. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey M.R. Endogenous somatostatin and the gut. Gut. 1986;27:457–467. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald P.E., El-Kholy W., Riedel M.J., Salapatek A.M., Light P.E., Wheeler M.B. The multiple actions of GLP-1 on the process of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51:S434–S442. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak A., Brasun J. Somatostatin analogues labeled with copper radioisotopes: current status. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2017;313:279–289. doi: 10.1007/s10967-017-5323-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C.R., Osadchiy V., Kalani A., Mayer E.A. The brain-gut-microbiome axis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;6:133–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawe G.M., Hoffman J.M. Serotonin signalling in the gut—functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;10:473–486. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley H.A., Matthis A.L., Enriquez J.R., Nichol J.T., Sanchez J.G., Stone W.J., Sundaram N., Helmrath M.A., Montrose M.H., Aihara E., et al. Enteroendocrine cells couple nutrient sensing to nutrient absorption by regulating ion transport. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4791. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18536-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros M.D., Turner A.J. Processing and metabolism of peptide-YY: pivotal roles of dipeptidylpeptidase-IV, aminopeptidase-P, and endopeptidase-24.11. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2088–2094. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.5.7908871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modvig I.M., Andersen D.B., Grunddal K.V., Kuhre R.E., Martinussen C., Christiansen C.B., Orskov C., Larraufie P., Kay R.G., Reimann F., et al. Secretin release after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reveals a population of glucose-sensitive S cells in distal small intestine. Int. J. Obes. 2020;44:1859–1871. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0541-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojsov S., Heinrich G., Wilson I.B., Ravazzola M., Orci L., Habener J.F. Preproglucagon gene expression in pancreas and intestine diversifies at the level of post-translational processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11880–11889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran T.H., Kinzig K.P. Gastrointestinal satiety signals II. Cholecystokinin. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G183–G188. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00434.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M., Cima I., Noti M., Fuhrer A., Jakob S., Dubuquoy L., Schoonjans K., Brunner T. The nuclear receptor LRH-1 critically regulates extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis in the intestine. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2057–2062. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji A., Kobiita A., Ye T., Chambon P. Homeostasis in intestinal epithelium is orchestrated by the circadian clock and microbiota cues transduced by TLRs. Cell. 2013;153:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller T.D., Finan B., Bloom S.R., D'Alessio D., Drucker D.J., Flatt P.R., Fritsche A., Gribble F., Grill H.J., Habener J.F., et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) Mol. Metab. 2019;30:72–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y., Harada N., Kishino S., Iwasaki K., Ikeguchi-Ogura E., Yamane S., Kato T., Kanemaru Y., Sankoda A., Hatoko T., et al. Medium-chain triglycerides inhibit long-chain triglyceride-induced GIP secretion through GPR120-dependent inhibition of CCK. iScience. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachawi N., Rao P.P., Makin V. The role of GLP-1 receptor agonists in managing type 2 diabetes. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2022;89:457–464. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.89a.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides N.C., Charmandari E., Kino T., Chrousos G.P. Stress-related and circadian secretion and target tissue actions of glucocorticoids: impact on health. Front. Endocrinol. 2017;8:70. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noti M., Corazza N., Mueller C., Berger B., Brunner T. TNF suppresses acute intestinal inflammation by inducing local glucocorticoid synthesis. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1057–1066. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noti M., Corazza N., Tuffin G., Schoonjans K., Brunner T. Lipopolysaccharide induces intestinal glucocorticoid synthesis in a TNFalpha-dependent manner. FASEB J. 2010;24:1340–1346. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-140913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa K., Kawabata-Shoda E., Doihara H., Kojima R., Okada H., Mochizuki S., Sano Y., Inamura K., Matsushime H., Koizumi T., et al. TRPA1 regulates gastrointestinal motility through serotonin release from enterochromaffin cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3408–3413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805323106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgaard A., Holst J.J. The role of somatostatin in GLP-1-induced inhibition of glucagon secretion in mice. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1731–1739. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4315-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posovszky C., Wabitsch M. Regulation of appetite, satiation, and body weight by enteroendocrine cells. Part 2: therapeutic potential of enteroendocrine cells in the treatment of obesity. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2015;83:11–18. doi: 10.1159/000369555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeld J.F. Gastrointestinal hormones and their targets. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;817:157–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann F., Tolhurst G., Gribble F.M. G-protein-coupled receptors in intestinal chemosensation. Cell Metab. 2012;15:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca A.S., Brubaker P.L. Role of the vagus nerve in mediating proximal nutrient-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1687–1694. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorsman P., Huising M.O. The somatostatin-secreting pancreatic delta-cell in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018;14:404–414. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S., Wright C.M., Heuckeroth R.O. Unexpected roles for the second brain: enteric nervous system as master regulator of bowel function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019;81:235–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021317-121515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior M. After GLP-1, what's next for weight loss? Nat. Biotechnol. 2023;41:740–743. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01818-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shajib M.S., Wang H., Kim J.J., Sunjic I., Ghia J.E., Denou E., Collins M., Denburg J.A., Khan W.I. Interleukin 13 and serotonin: linking the immune and endocrine systems in murine models of intestinal inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi B.H., Chatoo M., Xu X.K., Xu X., Chen X.Q. Versatile functions of somatostatin and somatostatin receptors in the gastrointestinal system. Front. Endocrinol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.652363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter Y., Tsubery H., Mironchik M., Rubinstein M., Fridkin M. Reversible PEGylation of peptide YY3-36 prolongs its inhibition of food intake in mice. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2439–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal M., Turturice B.A., Manzella C.R., Ranjan R., Metwally A.A., Theorell J., Huang Y., Alrefai W.A., Dudeja P.K., Finn P.W., et al. Serotonin transporter deficiency is associated with dysbiosis and changes in metabolic function of the mouse intestinal microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2138. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38489-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski R.M., Tuckey R.C., Manna P.R., Jetten A.M., Postlethwaite A., Raman C., Slominski A.T. Extra-adrenal glucocorticoid biosynthesis: implications for autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Genes Immun. 2020;21:150–168. doi: 10.1038/s41435-020-0096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn S.N., Mawe G.M. Non-conventional features of peripheral serotonin signalling – the gut and beyond. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;14:412–420. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert R.E., Feinle-Bisset C., Asarian L., Horowitz M., Beglinger C., Geary N. Ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, and PYY(3-36): secretory controls and physiological roles in eating and glycemia in health, obesity, and after RYGB. Physiol. Rev. 2017;97:411–463. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama Y., Mori Y., Nara M., Kotani Y., Nagai E., Kawada H., Kitamura M., Hirano R., Shimokawa H., Nakagawa A., et al. Gut bacterial aromatic amine production: aromatic amino acid decarboxylase and its effects on peripheral serotonin production. Gut Microbes. 2022;14 doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2128605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao E., Zhu Z., Hu C., Long G., Chen B., Guo R., Fang M., Jiang M. Potential roles of enterochromaffin cells in early life stress-induced irritable bowel syndrome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.837166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taves M.D., Otsuka S., Taylor M.A., Donahue K.M., Meyer T.J., Cam M.C., Ashwell J.D. Tumors produce glucocorticoids by metabolite recycling, not synthesis, and activate Tregs to promote growth. J. Clin. Invest. 2023;133 doi: 10.1172/JCI164599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry N., Margolis K.G. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating the GI tract: experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017;239:319–342. doi: 10.1007/164_2016_103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treichel A.J., Finholm I., Knutson K.R., Alcaino C., Whiteman S.T., Brown M.R., Matveyenko A., Wegner A., Kacmaz H., Mercado-Perez A., et al. Specialized mechanosensory epithelial cells in mouse gut intrinsic tactile sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:535–547. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.026. e513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther D.J., Bader M. A unique central tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M., Ding L., Wang D., Han J., Gao P. Serotonin: a potent immune cell modulator in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:186. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chandra R., Samsa L.A., Gooch B., Fee B.E., Cook J.M., Vigna S.R., Grant A.O., Liddle R.A. Amino acids stimulate cholecystokinin release through the Ca2+-sensing receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G528–G537. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00387.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann A., Allahyar A., Greiner T.U., Plovier H., Lunden G.O., Larsson T., Drucker D.J., Delzenne N.M., Cani P.D., Backhed F. Microbial modulation of energy availability in the colon regulates intestinal transit. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E.K., Chang R.B., Strochlic D.E., Umans B.D., Lowell B.B., Liberles S.D. Sensory neurons that detect stretch and nutrients in the digestive system. Cell. 2016;166:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C.K., Yusta B., Koehler J.A., Baggio L.L., McLean B.A., Matthews D., Seeley R.J., Drucker D.J. Divergent roles for the gut intraepithelial lymphocyte GLP-1R in control of metabolism, microbiota, and T cell-induced inflammation. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1514–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.08.003. e1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren A.M., Bloom S.R. Gut hormones and appetite control. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2116–2130. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Rayner C.K., Young R.L., Horowitz M. Gut motility and enteroendocrine secretion. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013;13:928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.S., Cho C.H., Yun M.S., Jang S.J., You H.J., Kim J.H., Han D., Cha K.H., Moon S.H., Lee K., et al. Akkermansia muciniphila secretes a glucagon-like peptide-1-inducing protein that improves glucose homeostasis and ameliorates metabolic disease in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:563–573. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.G., Liu J.X., Jia X.X., Geng J., Yu F., Cong B. Cholecystokinin octapeptide regulates the differentiation and effector cytokine production of CD4(+) T cells in vitro. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014;20:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Perkins M.H., Chang H., Han W., de Araujo I.E. An inter-organ neural circuit for appetite suppression. Cell. 2022;185:2478–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.05.007. e2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]