Abstract

The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) can bind to DNA or RNA, eliciting transcriptional activation/repression or rapid messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation, respectively. Although GR-mediated transcriptional regulation has been well-characterized, the molecular details of rapid mRNA degradation induced by glucocorticoids are not yet fully understood. Here, we demonstrate that glucocorticoid-induced GR-mediated mRNA decay (GMD) takes place in the nucleus and the cytoplasm, acting on pre-mRNAs and mRNAs. We also performed cross-linking and immunoprecipitation coupled with high-throughput sequencing analysis for GMD factors (GR, YBX1, and HRSP12) and mRNA sequencing analysis to identify endogenous GMD substrates. Our comprehensive coupled with high-throughput sequencing and mRNA sequencing analyses reveal that a range of cellular transcripts containing a common binding site for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 are preferential targets for GMD, suggesting possible new functions of GMD in various biological events.

Keywords: Glucocorticoid, Glucocorticoid receptor, Heat-responsive protein 12, messenger RNA decay, Proline-rich nuclear receptor 2

INTRODUCTION

It has long been appreciated that, at the molecular level, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is a multifaceted protein that acts on DNA as a transcription factor (Kato et al., 2011, Lonard and O'Malley, 2012). GR is largely distributed throughout the cytoplasm in quiescent cells. In the presence of a glucocorticoid (GC, a specific GR ligand), cytosolic GR binds to the GC. The resulting GC-GR complex then translocates to the nucleus and binds to a specific cis-acting DNA element, eliciting transcriptional activation or repression.

Although the GR binds to cis-acting DNA elements in a ligand-dependent manner, GR is also associated with a subset of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) under ligand-free conditions (Cho et al., 2015, Dhawan et al., 2007, Dhawan et al., 2012, Ishmael et al., 2011, Kino et al., 2010). In the presence of GC, mRNA-bound GR binds more strongly to the proline-rich nuclear receptor 2 (PNRC2). The GR-bound PNRC2 then functions as an adapter protein to recruit up-frameshift 1 (UPF1) and decapping mRNA 1a (DCP1A, a component of the decapping complex) to form complex I. Complex I then recruits additional cellular factors: Y-box-binding protein 1 (YBX1) and heat-responsive protein 12 (HRSP12, also known as reactive intermediate imine deaminase A homolog, UK114 antigen homolog, and a 14.5-kDa translational inhibitor protein). The sequential recruitment of these cellular factors leads to the formation of complex II. This resulting complex elicits the rapid degradation of GR-bound mRNAs through a process known as GR-mediated mRNA decay (GMD) (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016). Notably, this molecular mechanism plays a regulatory role in chemotaxis and atherosclerosis by targeting chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) mRNA (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016, Tang et al., 2022). In addition, GMD counteracts cellular mechanoresponses in a lncRNA-dependent manner by targeting mRNAs encoding bone morphogenic protein 7, Cbp/P300-interacting transactivator 2, and early growth response protein 1 (Zhu et al., 2021).

The GMD factors UPF1 and PNRC2 are multifunctional factors commonly involved in several other mRNA decay pathways, such as nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, which downregulates aberrant and natural transcripts harboring a premature termination codon, staufen-mediated mRNA decay, which degrades mRNAs containing an inter- or intramolecularly generated stem-loop structure for staufen binding in the 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR), replication-dependent histone mRNA decay, which occurs during the late S phase of the cell cycle or under genotoxic stress conditions, and m6A modification-mediated RNA degradation (Boo et al., 2022, Cho et al., 2013, Cho et al., 2012, Cho et al., 2009, Choe et al., 2014, Fatscher et al., 2015, Jung and Kim, 2023, Karam et al., 2013, Karousis et al., 2016, Kim and Maquat, 2019, Kwon et al., 2023, Lai et al., 2012, Lykke-Andersen and Jensen, 2015, Marzluff et al., 2008, Popp and Maquat, 2014, Shin et al., 2024). Although all of these decay pathways share UPF1 and PNRC2 for rapid mRNA degradation, GMD is unique in that it is an inducible RNA decay pathway upon treatment with GCs. In addition to its role in mRNA destabilization, UPF1 facilitates the replacement of the nuclear cap-binding complex with eIF4E, promoting efficient mRNP remodeling (Jeong et al., 2019) and protein quality control by triggering the accumulation of misfolded polypeptides in the aggresome (Chang et al., 2021, Hwang et al., 2023, Hwang et al., 2021, Park et al., 2017, Park et al., 2020, Park et al., 2018).

Because of the translation independence of GMD, the cis-acting element for GR binding might be sufficient to elicit the efficient GMD of a target mRNA in the presence of GCs. In this study, we investigate this possibility and demonstrate that GMD occurs in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. In addition, our transcriptome-wide analyses using cross-linking and immunoprecipitation coupled with high-throughput sequencing (CLIP-seq) of each GMD factor and mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) reveal that GMD targets pre-mRNA and cognate mRNA, as long as cellular transcripts contain a common binding site (CBS) for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12. In addition, in-depth analyses uncover a number of endogenous GMD substrates, highlighting the possible roles of GMD in diverse biological events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction

The following constructs have been reported previously: pCMV-MYC-UPF1 (Isken et al., 2008); pC5′-RLuc (Cho et al., 2015); and pCMV-MYC-HRSP12, pcDNA3-FLAG-HRSP12-WT, -P105A/R107E, pCMV-MYC-YBX1, and pC5′-RL-gGL (Park et al., 2016).

To construct the pC5′-MINX-RLuc plasmid, a DNA fragment containing CCL2 5′UTR sequences containing a CBS split by a MINX intron was synthesized by Integrated Device Technology. Its sequence is CTTAAGCTGCAGGAGGAACCGAGAGGCTGAGACTAACCCAGAAACATCCAATTCTCAAACTGAAGCTCGCACTCTCGguaagagccuagcauguagaacugguuaccugcagcccaagcuugcugcacgucuagggcgcaguaguccaggguuuccuugaugaugucauacuuauccugucccuuuuuuuuccacagCCTCCAGCATGACTTCGAA, where the underlined nucleotides specify the AflII and BstBI sites. The italicized nucleotides and lowercase letters denote the CCL2 5′UTR and MINX intron sequence, respectively. The synthesized DNA fragment was then digested with AflII/BstBI and ligated into the AflII/BstBI fragment of pC5′-RLuc.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HeLa and HAP1 cells were cultured in DMEM (HyClone) and IMDM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone), respectively. Cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Two days after transfection, the cells were harvested, and the total protein and RNA were isolated and purified as described previously (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016). Where indicated, the cells were treated with 100 nM dexamethasone (Dex, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 or 12 hours before cell harvesting.

To downregulate the expression of endogenous proteins, HeLa cells were transfected with 100 nM in vitro synthesized siRNA (Gene Pharma) using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). Three days later, the cells were harvested, and the total protein and RNA were purified.

siRNA Sequences

The following siRNA sequences were used in this study: 5′-r(ACAAUCCUGAUCAGAAACC)d(TT)-3′ for control (Boo et al., 2022, Park et al., 2019, Park et al., 2016), 5′-r(CCUAUGUGCUGGAAGGAAU)d(TT)-3′ for human GR (Park et al., 2016), and 5′-r(UGUAAUAGGGAGAGUUGAA)d(TT)-3′ for human HRSP12 (Boo et al., 2022, Park et al., 2019, Park et al., 2016).

Antibodies

Antibodies against the following proteins were used in this study: UPF1 (a gift from Lynne E. Maquat, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY), PNRC2 (Cho et al., 2009), DCP1A (Cho et al., 2012), GR (BD Biosciences, 611226), YBX1 (Cell Signaling Technology, D299), HRSP12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-31352), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, A5441), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; AbFrontier, LF-PA0212), MYC (Calbiochem, OP10L), and snRNP70 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed as previously described (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2017, Park et al., 2016). The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Nucleocytoplasmic Fractionation

Nucleocytoplasmic fractionation was performed using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunostaining

HeLa cells were cultured in media containing fetal bovine serum, which was charcoal-stripped to remove most hormones from the serum. The cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 minutes and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes. The cells were then incubated with 1.5% bovine serum albumin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in PBS for 1 hour, followed by incubation with primary antibodies against GR (BD Biosciences), MYC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and PNRC2 (Cho et al., 2009) in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488- or rhodamine-conjugated (Thermo Fisher Scientific) secondary antibodies for 1 hour, and the nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Biotium) for 5 minutes. The cells were mounted (Dako) and observed under a Zeiss confocal microscope (LSM 700). All the procedures were performed at room temperature.

CLIP-Seq

CLIP-seq experiments were conducted as previously described, with minor modifications (Murigneux et al., 2013, Park et al., 2019). Briefly, HeLa cells were irradiated with ultraviolet light (254 nm, 400 J/m2) using a ultraviolet light cross-linker before cell harvesting. The cross-linked cell pellets were then resuspended in lysis buffer (20.3 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM KH2PO4, 6.8 mM KCl, 342.5 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.5% NP-40 [pH 7.2]) and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. The cell extracts were mixed with 30 U of RNase-free DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes. Subsequently, 0.1 or 1.0 ng of RNase A (Affymetrix) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. After centrifugation at 13,000× g for 20 minutes at 4°C, the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation using protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) with bound antibodies. The beads were washed twice with lysis buffer and polynucleotide kinase (PNK) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% NP-40 [pH 7.4]).

To remove the phosphates from the ends of the RNAs, the beads were incubated with 3 U of alkaline phosphatase (Roche) for 10 minutes at 37°C. The beads were then washed twice with PNK+EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, and 20 mM EGTA [pH 7.4]) and twice with PNK buffer. For 5′-end phosphorylate of the RNAs, the beads were incubated with 40 U of T4 PNK (New England Biolabs) and 0.125 mM ATP in PNK buffer for 10 minutes at 37°C. The beads were then washed twice with PNK+EGTA buffer. Finally, the RNAs and proteins bound to the beads were denatured using lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen).

To purify the RNA covalently cross-linked to proteins, the samples were subjected to sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a Novex NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was excised to isolate proteins with molecular weights from the immunoprecipitated protein up to approximately 20 kDa above. The membrane piece was resuspended in PK buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, and 10 mM ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic acid [pH 7.4]) containing 4 mg/ml proteinase K (Roche), incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C, and further incubated in a PK/Urea buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic acid, and 7 M urea [pH 7.4]) for 20 minutes at 37°C. The soluble fractions were then subjected to organic solvent extraction and ethanol precipitation with GlycoBlue (Ambion) to isolate the RNA fragments.

Small-RNA libraries were constructed using a SMARTer smRNA-Seq Kit for Illumina (Clontech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quality checks of the complementary DNA libraries were performed with an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent). GR CLIP-seq was carried out using paired-end (2× 100 bp) sequencing, while MYC-YBX1 CLIP-seq and MYC-HRSP12 CLIP-seq were conducted using single-end (1× 50 bp) sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform (Illumina). Sequencing services were provided by Theragene (Republic of Korea) and Macrogen (Republic of Korea).

General Processing and Mapping of Reads

All sequencing data were processed in 2 steps: first, adapter and poly(A) sequences were trimmed using Cutadapt; second, ribosomal sequences were removed using riboPicker software (Schmieder et al., 2012) with a customized ribosomal RNA library. During adapter trimming, reads longer than 15 bp with Phred quality scores >30 were selected for further analysis. The processed reads were then mapped to a reference human genome (hg19) using STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2013). Only uniquely mapped reads were used for subsequent analyses. The number of reads before and after processing is summarized in Table S2.

Peak Analysis

To assess the distribution of GR-, YBX1-, and HRSP12-binding sites, we first performed peak calling using the Piranha peak-calling algorithm with parameters (-b 20 -a 0.85). Information on the annotations of mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) was obtained from 2 publicly available databases: RefSeq Genes (hg19, UCSC table browser [http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables]) and GENCODE (Release 19). Intronic regions were identified using the subtractBed module in bedtools v2.25.0 (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Six hierarchical genomic region categories were set based on the annotations: coding sequence (CDS) > 5′UTRs > 3′UTRs > lncRNAs > introns of mRNAs > intron of lncRNAs. The center of each peak was assigned to one of these categories using the intersectBed function in bedtools. To calculate relative peak enrichment, the number of peaks in each category was divided by the length of the corresponding genomic regions. For metagene analysis, the longest mRNA among the alternative isoforms (RefSeq Genes) was considered the representative. Peak centers were plotted in the corresponding regions: 5′UTR, CDS, and 3′UTR. Each region was binned into 50 segments and smoothed using the nearest-neighbor method (k = 3).

Integrative Data Analysis

For subsequent integrative analyses, only the peaks shown by both biological CLIP-seq replicates were considered. The peaks of GR, MYC-YBX1, and MYC-HRSP12 CLIP were initially extracted. Genes downregulated by Dex treatment were identified based on existing mRNA-seq data (SRP078311) (Park et al., 2016). Genes with fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads in all mRNA-seq data, and no CLIP peaks were defined as group I (negative control). To compute the log2 ratio of the siFactor (Dex +/−)/siControl (Dex +/−), genes with 0 fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped read values were ignored.

Gene Ontology Analysis

For gene ontology (GO) analysis, the list of group III genes was uploaded to DAVID (Huang da et al., 2009a, Huang da et al., 2009b) and investigated using a functional annotation tool. The resulting file was downloaded, and the GO terms and corresponding P values were acquired.

Motif Analysis

Consensus motif sequences were identified in 484 CBSs located within group III transcripts using the HOMER package (v4.8.3) (Heinz et al., 2010). Using the length option (12 bp), the top-3 consensus-binding motifs were identified based on their P values (Fig. S4).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed, equal-sample variance Student’s t-tests were performed to calculate the P values. Differences with P < .05 were considered statistically significant. For integrative data analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test was used.

Code Availability

All next-generation sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive of the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the accession number PRJNA1147324.

RESULTS

GMD Targets Pre-mRNA as Well as Its Spliced Form, mRNA

Previous studies using reporter mRNAs have shown that GMD triggers rapid mRNA degradation in a manner independent of (1) the position of the GR-binding site within a target mRNA and (2) a translation event (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016). These data led us to hypothesize that GMD may target pre-mRNA as well as cognate mRNA generated by splicing as long as the transcript contains a GR-binding site. To test the hypothesis, we first generated a GMD reporter construct, C5′-RL-gGl, which contained, in the following order, the full-length 5′UTR of CCL2 mRNA, the open-reading frame of the Renilla luciferase (RLuc) gene lacking a translation termination codon, and the genomic sequence of the β-globin (Gl) gene harboring 2 introns and a translation termination codon (UAA) in the last exon (Fig. 1A). HeLa cells transiently expressing C5′-RL-gGl were either untreated or treated with the synthetic GC derivative dexamethasone (Dex). Total cell RNAs were then purified and analyzed via qRT-PCR with specific oligonucleotides to amplify either the pre-mRNA or mRNA generated from the reporter construct. The results showed that the levels of both pre-mRNA and mRNA were comparably reduced after Dex treatment (Fig. 1B), suggesting that GMD occurs on pre-mRNA as well as mRNA. Consistent with these results, both pre-mRNAs and spliced mRNAs of previously identified cellular GMD targets (CCL2, CCL7, BCL3, and ZSWIM4) (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016) decreased in abundance upon Dex treatment (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the observed decreases were significantly reversed by the downregulation of a GMD factor, either GR or HRSP12, using a specific small-interfering RNA (siRNA, Fig. 1D and E). In contrast, the level of endogenous CCL5 mRNA, which lacks a GR-binding site (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016), was not affected by either Dex treatment or downregulation of a GMD factor. These data indicate that GMD targets both pre-mRNA and mRNA.

Fig. 1.

GMD targets both pre-mRNA and mRNA. (A) Schematic of C5′-RL-gGl, a GMD reporter construct containing 2 introns. Oligonucleotides for the amplification of pre-mRNA and its spliced mRNA are indicated by arrows. (B) GMD of pre-mRNA and mRNA. HeLa cells transiently expressing C5′-RL-gGl mRNAs, and as a control, firefly luciferase (FLuc) mRNA, were either untreated or treated with Dex for 12 hours before harvesting. The levels of C5′-RL-gGl pre-mRNA and mRNA were normalized to those of FLuc mRNAs. Normalized levels obtained from cells not treated with Dex were arbitrarily set to 100%. (C) Relative levels of endogenous pre-mRNA and mRNA of GMD target transcripts. HeLa cells were either treated or not treated with Dex for 1 hour before harvesting. The levels of endogenous pre-mRNA and mRNA of GMD target transcripts were normalized to the levels of GAPDH. Normalized levels obtained from cells not treated with Dex were arbitrarily set to 100%. (D and E) The effect of downregulation of GR or HRSP12 on GMD. (D) Specific downregulation of GR or HRSP12 using siRNA was confirmed via western blotting. For a quantitative comparison, 3-fold serial dilutions of total cell extracts were loaded in the 3 leftmost lanes. (E) The levels of endogenous pre-mRNA and mRNA of GMD target transcripts were normalized to those of endogenous GAPDH mRNAs. Endogenous CCL5 pre-mRNA and mRNA lacking a GR-binding site served as a negative control. The columns and bars in each panel represent the mean and standard deviation of 3 independent biological replicates (n = 3). Two-tailed, equal-sample variance Student’s t-tests were used to calculate the P values. **P < .01; *P < .05. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GMD, GR-mediated mRNA decay; GR, glucocorticoid receptor.

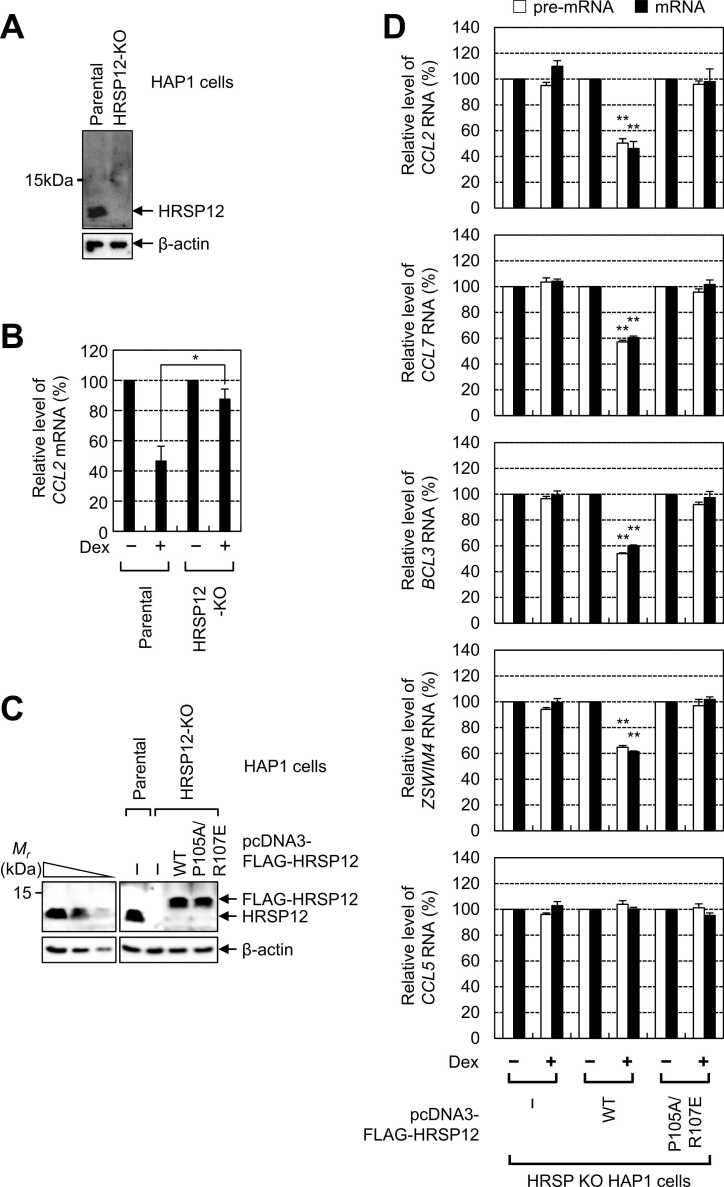

Efficient GMD of Pre-mRNA and Its Spliced mRNA Involves HRSP12 Trimerization

To clearly demonstrate that GMD targets pre-mRNA, we employed HRSP12-knockout (KO) HAP1 cells (Park et al., 2019), a near-haploid human cell line derived from a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia (Blomen et al., 2015, Carette et al., 2011, Elling and Penninger, 2014). The specific KO of HRSP12 was validated via western blotting with an α-HRSP12 antibody (Fig. 2A). As expected, Dex treatment reduced the level of endogenous CCL2 mRNA in parental HAP1 cells, but not in HRSP12 KO cells (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, complementation experiments with exogenously expressed FLAG-HRSP12-WT and its variant in HRSP12-KO HAP1 cells revealed that Dex treatment failed to induce GMD in both pre-mRNAs and the corresponding spliced mRNAs of previously identified cellular GMD targets (Fig. 2C and D), indicating the essential role of HRSP12 in the GMD of both pre-mRNA and mRNA. Notably, although exogenously expressed FLAG-HRSP12-WT restored GMD efficiency to a level comparable to that observed in the parental cells, exogenously expressed FLAG-HRSP12-P105A/R107E failed to restore GMD efficiency (Fig. 2C and D). Considering that the variant is not able to form a trimeric structure (Mistiniene et al., 2005, Park et al., 2019, Park et al., 2016) and cannot maintain the structural integrity necessary for a functionally active GMD complex (Park et al., 2016), our findings underscore the important role of HRSP12 trimerization in the efficient GMD of both pre-mRNA and mRNA.

Fig. 2.

GMD of both pre-mRNA and mRNA requires HRSP12 trimerization. (A and B) Effect of HRSP12 KO on the GMD of CCL2 mRNA. (A) Specific KO of HRSP12 in HAP1 cells was confirmed via western blotting. (B) GMD efficiency of endogenous CCL2 mRNA was analyzed via qRT-PCR. (C and D) Complementation experiments with FLAG-HRSP12-WT and -P105A/R107E. (C) Expression of FLAG-HRSP12-WT and its variant was comparable to that of endogenous HRSP12, as confirmed via western blotting. (D) GMD of pre-mRNA and mRNA of endogenous GMD target transcripts. n = 3; *P < .01; *P < .05. GMD, glucocorticoid receptor-mediated mRNA decay.

GMD Occurs in Both the Nucleus and Cytoplasm

Given that GMD acts on both pre-mRNA and mRNA (Fig. 1, Fig. 2), it is plausible that (1) all GMD factors may be located in the nucleus as well as the cytoplasm, and (2) GMD may occur both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. To test this hypothesis, cells, either untreated or treated with Dex, were fractionated into the nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. Next, the relative distribution of all known GMD factors was assessed via western blotting (Fig. 3A). The results showed that the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein U1 subunit 70 (snRNP70, a nuclear protein) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (a cytosolic protein) were enriched in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively, revealing the specificity of fractionation under our conditions. In line with other reports (Kato et al., 2011, Lonard and O'Malley, 2012), the majority of cytosolic GR was redistributed from the cytoplasm to the nucleus after Dex treatment, indicating that our Dex treatment conditions were effective. In contrast, all other proteins known to be involved in GMD, including UPF1, DCP1A, PNRC2, YBX1, and HRSP12, were largely enriched in the cytoplasmic fraction, and their intracellular distributions were not significantly affected by Dex treatment. It is worth noting, however, that significant proportions of GR and other GMD factors were still detectable in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively, even after Dex treatment. The preferential redistribution of GR from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon Dex treatment and the Dex-insensitive cytoplasmic distribution of other GMD factors were confirmed using immunostaining assays (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

GMD occurs both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Extracts of HeLa cells treated or not treated with Dex for 1 hour were fractionated into the nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) extracts. (A) The distribution of GMD factors was determined via western blotting. All results are representative of 3 biological replicates. (B) The GMD of pre-mRNA and mRNA among GMD target transcripts in the nucleus and cytoplasm was analyzed by qRT-PCR. n = 3; **P < .01; *P < .05. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GMD, GR-mediated mRNA decay; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR.

Next, we assessed GMD efficiency using the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of HeLa cells. The results revealed that, although GMD efficiency varied among GMD substrates and by fraction, both pre-mRNAs and mRNAs of all the tested GMD substrates, except ZSWIM4, were significantly downregulated in both the nucleus and cytoplasm upon Dex treatment (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that GMD occurs in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm. In the case of ZSWIM4, pre-mRNA and mRNA levels were downregulated only in the nuclear fraction after Dex treatment. A simple interpretation of these results is that a putative RNA-binding protein in the cytoplasm may disrupt complex formation between the GMD complex and ZSWIM4 mRNA.

CLIP-Seq of GMD Factors in Human Cells

Considering that efficient GMD requires the presence of a GR-binding site within the transcript, we next determined the specific and direct interactions between cellular transcripts and GMD factors (GR, YBX1, and HRSP12) at the transcriptome level. Previous studies have shown that, although GR binds to GMD substrates in a ligand-independent manner, the interactions of YBX1 and HRSP12 with GMD substrates are promoted by the presence of a ligand (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016). Therefore, we performed 2 biological replicates of the CLIP-seq experiments (CLIP1 and CLIP2) on HeLa cells, either untreated (for CLIP-seq experiments with GR) or treated with Dex (for CLIP-seq experiments with MYC-YBX1 and MYC-HRSP12). The specificity of immunoprecipitation using antibodies against endogenous GR or the MYC tag was confirmed via western blotting (Fig. S2A-C). In each CLIP-seq assay, approximately 18.7 to 36.4 million raw reads were generated by high-throughput sequencing (Table S2). After the stepwise processing of the raw reads (see the “MATERIALS AND METHODS” section for details), we successfully obtained approximately 0.8 to 1.8 million uniquely mapped reads from each CLIP-seq assay (Table S2). Notably, the Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between CLIP1 and CLIP2 for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 in terms of the number of uniquely mapped reads per gene were >0.800, indicating strong correlations between the 2 biological replicates of the CLIP-seq experiment (Fig. 4A-C).

Fig. 4.

CLIP-seq analysis of endogenous GR, MYC-YBX1, and MYC-HRSP12 in HeLa cells. CLIP-seq experiments were conducted as described in the Materials and Methods section. (A-C) Scatter plots of reads obtained for individual genes. All CLIP-seq experiments with endogenous GR (A), MYC-YBX1 (B), and MYC-HRSP12 (C) were performed on 2 biological replicates. Each dot represents a gene. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) are indicated. (D-F) Relative peak distributions of GR (D), YBX1 (E), and HRSP12 (F). The number of peaks shown in Figures S2D-F was divided by the length of nucleotides of each region in the genome. 3′UTR, 3′-untranslated region; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HRSP12, heat-responsive protein 12; YBX1, Y-box-binding protein 1.

Using the uniquely mapped reads, we assessed the binding preferences of GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 to various regions of the transcripts. We first conducted peak calling and successfully obtained approximately 5,200 to 28,000 peaks from each CLIP-seq (Table S2). The positions of the peaks in the transcripts were categorized into 5′UTRs, CDSs, 3′UTRs, introns of a protein-coding gene, ncRNAs, or introns of ncRNA. Supporting our observation that GMD targets both pre-mRNA and mRNA (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3), most of the called peaks for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 from the CLIP-seq data were mapped to the introns of a protein-coding gene (Fig. S2D-F). Of note, when adjusting the number of peaks for the nucleotide length of the regions, the peaks obtained from the CLIP-seq data of GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 were significantly enriched in the 5′UTR and CDS regions (Fig. 4D-F). These results suggest that GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 preferentially bind to the 5′UTR and CDS at the transcriptome level.

Transcripts Harboring a Common Binding Site for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 Are Preferential Targets of GMD

To investigate the transcriptome-wide roles of GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 in GMD, we analyzed the peaks common to GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 in 2 independent CLIP-seq experiments (CLIP1 and CLIP2). We successfully identified 2,850, 5,205, and 11,090 peaks that overlapped between the CLIP1 and CLIP2 data from GR, YBX1, and HRSP12, respectively (Fig. 5A and Table S3). At the transcript level, GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 bound to 2,202, 3,930, and 7,253 genes, respectively (Fig. 5B). Among these, 697, 1,264, and 2,299 genes were downregulated upon Dex treatment (Fig. 5C). Moreover, 1,768 peaks (62% of the 2,850 peaks that overlapped between the 2 GR CLIP-seq experiments; Fig. 5, Fig. 1), 1,315 genes (60% of the 2,202 genes that overlapped between the 2 GR CLIP-seq experiments; Fig. 5B), and 419 genes downregulated upon Dex treatment (60% of the 697 genes downregulated by Dex treatment and overlapped between the 2 GR CLIP-seq experiments; Fig. 5C) were shared among GR, YBX1, and HRSP12, indicating a significant overlap among these 3 sets of binding sites (for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12). Of note, in agreement with previous reports (Cho et al., 2015, Dhawan et al., 2007, Dhawan et al., 2012, Ishmael et al., 2011, Kino et al., 2010, Park et al., 2016), we observed a strong enrichment of the common peaks in the 5′UTR of CCL2 mRNA (Fig. S3A).

Fig. 5.

A common binding site for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 is essential for efficient GMD. (A-C) In the transcriptome-wide analysis of CLIP-seq data on GR, YBX1, and HRSP12, only the peaks that overlapped from 2 biological replicates of each CLIP-seq experiment were selected. The Venn diagrams display the number of peaks (A), the number of genes (B), which have the corresponding peaks, and the number of genes (C), which have the corresponding peaks and are downregulated after Dex treatment. (D-F) Cumulative distribution function plots for GMD factor dependency. Fold-change values in transcript levels following Dex treatment were normalized to those without Dex treatment. Next, the relative fold changes after downregulation of GR (siGR, D), YBX1 (siYBX1, E), or HRSP12 (siHRSP12, F) were further normalized to those before downregulation. The relative changes were compared among group I (black), group II (blue), and group III (red). P values were calculated using the 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test. (G and H) Box plot analysis shows that GMD is independent of the position (G) and the number of (H) the common peaks. 3′UTR, 3′-untranslated region; 5′UTR, 5′-untranslated region; CDS, coding sequence; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HRSP12, heat-responsive protein 12; YBX1, Y-box-binding protein 1.

To test whether transcripts harboring a CBS for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 are subjected to GMD, we analyzed the effect of downregulating GR, YBX1, or HRSP12 on the levels of transcripts, which were categorized into 3 groups: group I (transcripts lacking any binding sites for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12), group II (transcripts downregulated by Dex treatment and overlapping between the 2 GR CLIP-seq experiments), and group III (transcripts harboring a CBS for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 and downregulated by Dex treatment). Cumulative fraction analysis showed that the downregulation of GR, YBX1, or HRSP12 significantly increased the levels of both group II and group III transcripts compared with group I transcripts (Fig. 5D-F), indicating that the transcripts harboring CBS are preferentially targeted by GMD.

Using group III transcripts, we next evaluated the correlations between the relative position or number of common peaks and transcript levels. Consistent with previous data (Cho et al., 2015, Park et al., 2016), the abundance of group III transcripts was not significantly affected by the relative positions or numbers of the common peaks (Fig. 5G and H). The position independence of GMD was further demonstrated by measuring the change in the levels of group III transcripts harboring CBS at different positions using qRT-PCR (Fig. S3B).

We also performed GO term enrichment analysis of the group III transcripts. The results suggested that these transcripts were significantly enriched in GO terms for cellular metabolic process, nitrogen compound metabolic process, and single-organism cellular process in biological processes, and nucleotide binding in molecular functions (Fig. S3C). This suggests that GMD regulates various cellular transcripts, affecting various biological processes.

Efficient GMD Requires an Intact Form of a CBS for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12

Our transcriptome-wide analysis revealed that GMD reduces the levels of both pre-mRNA and mRNA as long as the transcript contains a CBS. To further assess the role of a CBS for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 in GMD, we generated 2 GMD reporter constructs, C5′-RLuc and C5′-MINX-RLuc, both of which contained the full-length 5′UTR of CCL2 mRNA followed by an open-reading frame of the RLuc gene (Fig. 6A). The C5′-RLuc reporter contained the full-length 5′UTR of the CCL2 mRNA harboring an intact CBS. In the case of the C5′-MINX-RLuc reporter, on the other hand, the CBS was split by inserting a MINX intron sequence. Therefore, although C5′-MINX-RLuc pre-mRNA would not be targeted for GMD due to a lack of an intact CBS, C5′-MINX-RLuc mRNA is expected to be degraded by GMD because an intact CBS is generated by removal of the MINX intron after splicing. As expected, the qRT-PCR results showed that although both C5′-RLuc mRNA and C5′-MINX-RLuc mRNA were comparably downregulated, C5′-MINX-RLuc pre-mRNA was not affected by Dex treatment (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

GMD requires an intact CBS. (A) Schematic of a GMD reporter construct containing a CBS split by an intron. The full-length CCL2 5′UTR and CBS are indicated in red and yellow, respectively. Oligonucleotides for the amplification of pre-mRNA and its spliced mRNA are indicated by the arrows. (B) qRT-PCR of pre-mRNA and mRNA generated from the GMD reporter construct. (C and D) Read maps for transcripts harboring a CBS split by an intron. The reads obtained from each CLIP-seq experiment were mapped to the UCSC reference genome (hg19). Read maps for the HYI (C) and CCBE1 (D) transcripts are shown. Genomic regions corresponding to the identified peaks are underlined in green. (E) Validation for the GMD of newly identified transcripts containing a CBS split by an intron. Cellular transcripts containing a CBS split by an intron were identified in the CLIP-seq data. The efficiency of GMD of pre-mRNA and mRNA among the identified transcripts was analyzed via qRT-PCR. n = 3; **P < .01; *P < .05. 5′UTR, 5′-untranslated region; CBS, common binding site; GMD, glucocorticoid receptor-mediated mRNA decay; HRSP12, heat-responsive protein 12; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; YBX1, Y-box-binding protein 1.

To further corroborate our findings, we selected endogenous transcripts harboring CBS (in the CLIP-seq data), whose centers were located within 5 nucleotides upstream or downstream of an exon-exon junction. We successfully identified 9 transcripts with this criterion, including HYI and CCBE1 (Table S4). For the pre-mRNAs of these transcripts, the CBSs were split into 2 parts by an intron. An intact CBS was expected to form only after splicing. Therefore, it is likely that mRNAs, but not the pre-mRNAs of these transcripts, can be targeted for GMD. Indeed, the qRT-PCR results showed that only the spliced forms of HYI and CCBE1 transcripts were downregulated by Dex treatment (Fig. 6C-E). These data clearly show that efficient GMD requires intact CBS for the binding of GR, YBX1, and HRSP12.

DISCUSSION

Here, we describe a transcriptome-wide analysis of GMD using CLIP-seq with the GMD factors GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 (Fig. 4). Our data showed that cellular transcripts containing CBSs for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 are preferential targets for GMD (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). We also observed that all tested GMD factors are located in both the nucleus and cytoplasm; accordingly, GMD occurred in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Based on these observations, we concluded that if a transcript contains a CBS for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12, GMD can target pre-mRNA (in the nucleus) and mRNA (both in the nucleus and cytoplasm). In addition, we found that GMD occurs independently of the position and the number of CBSs within a transcript (Fig. 5G and H). These molecular properties of GMD may contribute to the regulation of GMD substrate expression. For instance, if the CBS is in an intron, the pre-mRNA may be targeted for GMD; consequently, its spliced product, mRNA, can also be downregulated. On the other hand, if the CBS is in an exon, both the pre-mRNA and mRNA are expected to be targeted for GMD. If the CBS is split by an intron, only the mRNA can be targeted for GMD, as shown in Figure 6.

We searched for putative consensus motif sequences using 484 CBSs located within the group III transcripts (Fig. 5C). Although we identified several consensus motifs with significant P values calculated using the HOMER program, fewer than 3% of the 484 peaks contained consensus motifs (Fig. S4). A possible explanation for this observation is that the secondary or tertiary structure of the RNA mostly contributes to the specific loading of GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 onto GMD target transcripts. In support of this idea, one report showed that the GR is directly associated with a secondary or tertiary structure located almost at the 3′-end of the growth arrest-specific 5 (GAS5) ncRNAs (Kino et al., 2010).

In our transcriptome-wide analyses of CLIP-seq and mRNA-seq data, we identified 1,315 genes, the transcripts of which contain CBSs for GR, YBX1, and HRSP12 (Fig. 5B). Among these, 419 transcripts (31.9%) were downregulated by Dex treatment (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that although the presence of a CBS is essential for efficient GMD, additional unknown factors may be involved in the recognition of GMD substrates and the activation of the GMD complex. In addition, we found that 1,134 of 3,930 genes (28.9%) from YBX1 CLIP-seq and 4,043 of 7,253 genes (55.7%) from HRSP12 CLIP-seq contain unique binding sites for YBX1 and HRSP12, respectively (Fig. 5B). Considering that YBX1 and HRSP12 are multifunctional proteins that participate in various molecular and cellular processes (Boo et al., 2022, Boo and Kim, 2020, Chen et al., 2019, Eliseeva et al., 2011, Lyabin et al., 2014, Park et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2019), it is plausible that cellular RNAs harboring unique binding sites for YBX1 or HRSP12 may be targeted by RNA-related pathways other than GMD.

In summary, this study provides transcriptome-wide evidence highlighting the essential role of GR-, YBX1-, and HRSP12 binding to the CBS in facilitating efficient GMD. Our findings shed light on the potential functions of GMD in various biological events.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sung Ho Boo: Writing–original draft, validation, investigation, formal analysis, and conceptualization. Min-Kyung Shin: Visualization, validation, investigation, formal analysis, and conceptualization. Hongseok Ha: Software, data curation. Jae-Sung Woo: Writing–original draft, supervision. Yoon Ki Kim: Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, supervision, project administration, and conceptualization.

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The author Yoon Ki Kim is an Associate Editor for Molecules and Cells and was not involved in the editorial review or the decision to publish this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (MIST) (RS-2024-00442502).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.mocell.2024.100130.

Contributor Information

Jae-Sung Woo, Email: jaesungwoo@korea.ac.kr.

Yoon Ki Kim, Email: yk-kim@kaist.ac.kr.

ORCID

Sung Ho Boo https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1717-902X

Min-Kyung Shin https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9335-5137

Hongseok Ha https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0923-9187

Jae-Sung Woo https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9163-3433

Yoon Ki Kim https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1303-072X

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- Blomen V.A., Májek P., Jae L.T., Bigenzahn J.W., Nieuwenhuis J., Staring J., Sacco R., van Diemen F.R., Olk N., Stukalov A., et al. Gene essentiality and synthetic lethality in haploid human cells. Science. 2015;350:1092–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boo S.H., Ha H., Kim Y.K. m(1)A and m(6)A modifications function cooperatively to facilitate rapid mRNA degradation. Cell Rep. 2022;40 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boo S.H., Kim Y.K. The emerging role of RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020;52:400–408. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0407-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette J.E., Raaben M., Wong A.C., Herbert A.S., Obernosterer G., Mulherkar N., Kuehne A.I., Kranzusch P.J., Griffin A.M., Ruthel G., et al. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature. 2011;477:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Hwang H.J., Kim B., Choi Y.G., Park J., Park Y., Lee B.S., Park H., Yoon M.J., Woo J.S., et al. TRIM28 functions as a negative regulator of aggresome formation. Autophagy. 2021;17:4231–4248. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1909835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li A., Sun B.F., Yang Y., Han Y.N., Yuan X., Chen R.X., Wei W.S., Liu Y., Gao C.C., et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2019;21:978–990. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H., Han S., Choe J., Park S.G., Choi S.S., Kim Y.K. SMG5-PNRC2 is functionally dominant compared with SMG5-SMG7 in mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1319–1328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H., Kim K.M., Han S., Choe J., Park S.G., Choi S.S., Kim Y.K. Staufen1-mediated mRNA decay functions in adipogenesis. Mol. Cell. 2012;46:495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H., Kim K.M., Kim Y.K. Human proline-rich nuclear receptor coregulatory protein 2 mediates an interaction between mRNA surveillance machinery and decapping complex. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H., Park O.H., Park J., Ryu I., Kim J., Ko J., Kim Y.K. Glucocorticoid receptor interacts with PNRC2 in a ligand-dependent manner to recruit UPF1 for rapid mRNA degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112:E1540–1549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409612112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe J., Ahn S.H., Kim Y.K. The mRNP remodeling mediated by UPF1 promotes rapid degradation of replication-dependent histone mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9334–9349. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan L., Liu B., Blaxall B.C., Taubman M.B. A novel role for the glucocorticoid receptor in the regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10146–10152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan L., Liu B., Pytlak A., Kulshrestha S., Blaxall B.C., Taubman M.B. Y-box binding protein 1 and RNase UK114 mediate monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 mRNA stability in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:3768–3775. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00846-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliseeva I.A., Kim E.R., Guryanov S.G., Ovchinnikov L.P., Lyabin D.N. Y-box-binding protein 1 (YB-1) and its functions. Biochemistry. 2011;76:1402–1433. doi: 10.1134/S0006297911130049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elling U., Penninger J.M. Genome wide functional genetics in haploid cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2415–2421. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatscher T., Boehm V., Gehring N.H. Mechanism, factors, and physiological role of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Cell. and Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:4523–4544. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y.C., Laslo P., Cheng J.X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H.J., Park T.L., Kim H.I., Park Y., Kim G., Song C., Cho W.K., Kim Y.K. YTHDF2 facilitates aggresome formation via UPF1 in an m(6)A-independent manner. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:6248. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42015-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H.J., Park Y., Kim Y.K. UPF1: from mRNA surveillance to protein quality control. Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9080995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishmael F.T., Fang X., Houser K.R., Pearce K., Abdelmohsen K., Zhan M., Gorospe M., Stellato C. The human glucocorticoid receptor as an RNA-binding protein: global analysis of glucocorticoid receptor-associated transcripts and identification of a target RNA motif. J. Immunol. 2011;186:1189–1198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isken O., Kim Y.K., Hosoda N., Mayeur G.L., Hershey J.W., Maquat L.E. Upf1 phosphorylation triggers translational repression during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Cell. 2008;133:314–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong K., Ryu I., Park J., Hwang H.J., Ha H., Park Y., Oh S.T., Kim Y.K. Staufen1 and UPF1 exert opposite actions on the replacement of the nuclear cap-binding complex by eIF4E at the 5′ end of mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:9313–9328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung I., Kim Y.K. Exon junction complex is a molecular compass of N(6)-methyladenosine modification. Mol. Cells. 2023;46:589–591. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2023.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam R., Wengrod J., Gardner L.B., Wilkinson M.F. Regulation of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: implications for physiology and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1829:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karousis E.D., Nasif S., Muhlemann O. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: novel mechanistic insights and biological impact. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2016;7:661–682. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S., Yokoyama A., Fujiki R. Nuclear receptor coregulators merge transcriptional coregulation with epigenetic regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.K., Maquat L.E. UPFront and center in RNA decay: UPF1 in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and beyond. RNA. 2019;25:407–422. doi: 10.1261/rna.070136.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T., Hurt D.E., Ichijo T., Nader N., Chrousos G.P. Noncoding RNA gas5 is a growth arrest- and starvation-associated repressor of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H.C., Bae Y., Lee S.V. The role of mRNA quality control in the aging of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cells. 2023;46:664–671. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2023.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T., Cho H., Liu Z., Bowler M.W., Piao S., Parker R., Kim Y.K., Song H. Structural basis of the PNRC2-mediated link between mrna surveillance and decapping. Structure. 2012;20:2025–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard D.M., O'Malley B.W. Nuclear receptor coregulators: modulators of pathology and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012;8:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyabin D.N., Eliseeva I.A., Ovchinnikov L.P. YB-1 protein: functions and regulation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2014;5:95–110. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke-Andersen S., Jensen T.H. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: an intricate machinery that shapes transcriptomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16:665–677. doi: 10.1038/nrm4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzluff W.F., Wagner E.J., Duronio R.J. Metabolism and regulation of canonical histone mRNAs: life without a poly(A) tail. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:843–854. doi: 10.1038/nrg2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistiniene E., Pozdniakovaite N., Popendikyte V., Naktinis V. Structure-based ligand binding sites of protein p14.5, a member of protein family YER057c/YIL051c/YjgF. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2005;37:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murigneux V., Sauliere J., Roest Crollius H., Le Hir H. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA binding sites by CLIP-seq. Methods. 2013;63:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Park Y., Ryu I., Choi M.H., Lee H.J., Oh N., Kim K., Kim K.M., Choe J., Lee C., et al. Misfolded polypeptides are selectively recognized and transported toward aggresomes by a CED complex. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park O.H., Do E., Kim Y.K. A new function of glucocorticoid receptor: regulation of mRNA stability. BMB Rep. 2015;48:367–368. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.7.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park O.H., Ha H., Lee Y., Boo S.H., Kwon D.H., Song H.K., Kim Y.K. Endoribonucleolytic cleavage of m(6)A-containing RNAs by RNase P/MRP complex. Mol. Cell. 2019;74:494–507.e498. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park O.H., Park J., Yu M., An H.T., Ko J., Kim Y.K. Identification and molecular characterization of cellular factors required for glucocorticoid receptor-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 2016;30:2093–2105. doi: 10.1101/gad.286484.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Park J., Hwang H.J., Kim B., Jeong K., Chang J., Lee J.B., Kim Y.K. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay factor UPF1 promotes aggresome formation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3106. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16939-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Park J., Kim Y.K. Crosstalk between translation and the aggresome-autophagy pathway. Autophagy. 2018;14:1079–1081. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1358849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp M.W., Maquat L.E. The dharma of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in mammalian cells. Mol. Cells. 2014;37:1–8. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder R., Lim Y.W., Edwards R. Identification and removal of ribosomal RNA sequences from metatranscriptomes. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:433–435. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M.K., Chang J., Park J., Lee H.J., Woo J.S., Kim Y.K. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of mRNAs encoding a signal peptide occurs primarily after mRNA targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cells. 2024;47 doi: 10.1016/j.mocell.2024.100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Li Z., Yang H., Yang Y., Geng C., Liu B., Zhang T., Liu S., Xue Y., Zhang H., et al. YB1 dephosphorylation attenuates atherosclerosis by promoting CCL2 mRNA decay. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.945557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wang L., Han X., Yang W.L., Zhang M., Ma H.L., Sun B.F., Li A., Xia J., Chen J., et al. RNA 5-methylcytosine facilitates the maternal-to-zygotic transition by preventing maternal mRNA decay. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:1188–1202.e1111. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Li J., Li Y., Zheng Z., Guan H., Wang H., Tao K., Liu J., Wang Y., Zhang W., et al. Glucocorticoid counteracts cellular mechanoresponses by LINC01569-dependent glucocorticoid receptor-mediated mRNA decay. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd9923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material