Abstract

Background

The present study is an intervention-based qualitative study that explores the factors causing depression among antenatal women and analyses coping strategies based on the modified version of the Thinking Healthy Programme (THP) intervention in the urban setting of Lahore, Pakistan.

Methods

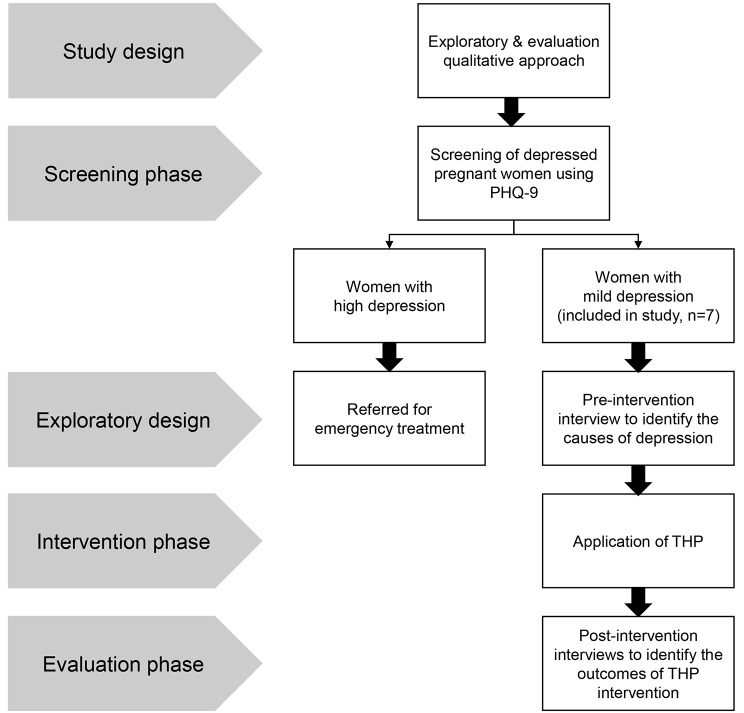

An exploratory qualitative evaluation approach was used in the present study. The study comprises four phases, i.e., the screening phase, exploratory phase, intervention phase, and evaluation phase. During the first phase, pregnant women aged 18–45 years were screened for anxiety and depression by using the Urdu-translated Patient Health Care Questionnaire-9. In the second phase, identified women were interviewed to explore the factors responsible for depression. In the third phase, the intervention was administered via the THP intervention. In the last phase, the same women were reinterviewed to analyse the outcomes of the intervention. Thematic analysis was performed for the analysis of the interviews.

Results

Data was analyzed using thematic analysis following an deductive and indictive approach in both pre- and post-intervention phase. Three main themes emerged in the pre-intervention phase: (1) the impact of adverse life events on the mental health of pregnant women, (2) the adverse effects of marital relationship issues on pregnant women, and (3) depression-causing factors due to the joint family system. Furthermore, four themes emerged in the post-intervention stage: (1) development of positivity in thinking and attitude, (2) learning about stress management through the provision of compassion and sharing avenues, (3) gaining self-esteem to address matters positively, and (4) improving relationships with the unborn child and family. Numerous pregnant women praised the THP project and recommended that hospitals adopt it to assist pregnant patients in the Pakistani health system.

Conclusion

The study concludes that THP can be a valuable tool for helping many pregnant women who are experiencing prenatal depression recover, however, there is a further need for exploring its benefits in varying social and cultural contexts.

Trial registration

The study has been registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (NCT04663243).

Keywords: Pregnancy, Depression and anxiety, Power of decision, Sociocultural environment, Social support

Background

Antenatal depression (AD) is a significant concern in public health in developing countries. Pregnant women are more prone to different psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression. However, these issues are more prevalent in developing countries such as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh than in other developed and high-income countries [1]. Statistics have revealed that AD is dependent on income groups across countries, with a 30% prevalence of AD in low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), a 24% prevalence in upper-middle-income countries, and an 18% prevalence in high-income countries [2].

The reasons behind the high prevalence of AD in LMICs could be traced to improper antenatal care given depressive symptoms, lack of an integrated healthcare system, and lack of acknowledgement and understanding of ill mental health conditions [3]. The healthcare-seeking patterns of mothers and children are also affected by maternal depressive symptoms combined with AD in women, resulting in poor health outcomes and low birth weight [4]. Previous research revealed that depressed women have a greater risk of preterm birth, giving birth to a child with lower birth weight, and intrauterine growth than women who do not experience symptoms of depression [5].

Many quantitative studies have been performed to highlight different AD symptoms and their causes. Previous quantitative studies have demonstrated various predictors of depression in pregnant women, including poverty, poor intimate relationships, intimate partner violence, inadequate emotional support from family, lack of assistance in adverse situations, social distress, financial problems, lack of autonomy in making household decisions due to husbands’ and mothers-in-laws’ authoritative behaviour, family history of psychiatric illness, previous history of miscarriage or stillbirth and unplanned pregnancy [6–9]. In addition, preferences for male children and lack of freedom for women to use family planning techniques for reproductive health are additional factors in AD among pregnant women in the patriarchal system of Pakistani society [10]. Other socioeconomic factors contributing to increasing rates of AD among pregnant women in Pakistan include no autonomy to access husbands’ earnings, unstable husbands’ employment, food insecurity, rented houses, or not having adequate money to buy a house [11].

Considering the alarming incidence of AD in LMICs, including Pakistan, different measures are being taken to address this issue. Similarly, to reduce the incidence of AD and prevent its hazardous effects on maternal and child health, the World Health Organization (WHO) designed the Thinking Healthy Programme (THP). This is a psychological intervention program intended to reduce depressive symptoms among pregnant women. It employs the core principles and techniques of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), such as building an empathetic relationship, focusing on the here and now, behaviour activation and problem-solving. The programme is fully manualised and has culturally appropriate pictorial illustrations aimed at helping mothers reflect on their thinking process and encouraging family support [6].

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, very few studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of this program in reducing AD levels among pregnant women. These studies claim that the intervention has a moderate to minimal effect on lowering AD levels [12, 13]. Pooled analysis of THP trials in Pakistan and India reflects the suitability of this program in low socio-economic and low literacy rate population of rural and urban areas [12]. In Peru and Vietnam, a pilot research was done to check the adaptability and acceptability of THP in rural Vietnamese people. These studies found the content and methodology highly relevant to local needs and encouraged the concept as a mental health promotion strategy that could be integrated into local universal mother and child health care mothers [14, 15]. All of the little evidence available on this topic is quantitative; however, there is a dearth of qualitative research exploring the complex mechanism of depression in women during pregnancy in developing countries such as Pakistan, as well as the effectiveness of THP. Given this, and the rich cultural dynamics of the country, the specific focus of the current study was to evaluate the impact of modified version of the THP on the mental state of preidentified pregnant women and to explore the causes of AD among them.

Methods

Study design

This paper is part of a broader quasi-experimental study conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the THP intervention for reducing depressive symptoms among pregnant women in urban clinical settings. The present paper uses an exploratory qualitative evaluation approach to explore the causes of AD and to evaluate the effectiveness of psychotherapy sessions among pregnant women with depression. This approach helps uncover the complexities of human experiences, beliefs, and behaviors that quantitative methods might miss [16]. Seven married and pregnant women aged 18–45 years were recruited from the gynaecological outpatient departments assessment room in the Public Tertiary Care Hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. In addition, purposive and random sampling techniques were used in the present study. This intervention-based study was conducted in four phases: (1) a screening phase, (2) an exploratory phase, (3) an intervention phase, and (4) an evaluation phase.

Phase 1: screening

The first phase involved screening pregnant women for depression. 24–26 weeks pregnant women were screened and assessed for depression by using the Patient Health Care Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is a pre-developed tool, used specifically for pregnant women. Women who understood the Urdu language and had PHQ-9 scores 10–19 were assessed as positive for depression (moderate depression) and were included in the study. Pregnant women who had a learning disability with a PHQ-9 score 20 or higher and had serious medical conditions were referred for emergency treatment and were excluded from participation in the study. Those women who had a PHQ-9 score of less than 10, were assessed as minimal or no depression and were also excluded from the study. Furthermore, women who had prior history of mental illness and those who declined consent were not included in the study.

Phase 2: exploration

The exploratory phase included pre-intervention exploratory, descriptive interviews with the selected women based on a semistructured interview guide. During this phase, factors related to depression among pregnant women were explored.

Phase 3: intervention

During the third phase of the present study, the THP intervention was applied. THP is a CBT-based intervention that the WHO mainly designed to reduce perinatal depression in low socioeconomic settings [6]. The THP intervention comprises sixteen sessions based on five modules. However, according to the sociocultural context of Pakistan and identified causes of antenatal depression among pregnant women in the pre-intervention phase of the study, a modified version of the THP comprising only four sessions were included: (1) psychoeducation and stress management, (2) personal well-being, (3) social support, and (4) mother-infant bonding. In total, four sessions were given to the recruited females. The first two sessions were given to pregnant women at 24–26 + 6 weeks, while two booster sessions were conducted in the third trimester for the participants for interactive discussions and practical exercises. Considering the societal pressure and stigma associated with the mental health issues in Pakistan, all the sessions were arranged within the premises of the health facility during the routine antenatal visit of the participants. Before conducting the sessions, permissions from the participants and their husbands were taken, given the patriarchal structure of Pakistani society and considering the ease and comfort of the participants.

Phase 4: evaluation

The last phase was the evaluation phase, in which interviews with the same women were conducted after the interventions took place to analyse and evaluate the outcome of the THP intervention.

Research site

The screening session (assessment of depression among women), pre- and post-intervention, and THP intervention were conducted in the Assessment Room of the Obstetrics & Gynaecology Outdoor Department of a Public Tertiary Care Hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. No prior relationship was established with the participants before the study, and participants were randomly selected from the hospital’s ward. To ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the participants, the research activities in all phases took place in the private space in the assessment room, and no other person was allowed to sit there except for the researchers and participants.

Interview guide and data collection

Face-to-face, in-depth semistructured interviews were conducted with the recruited women during the exploratory and evaluation phases of the study. Before the initiation of the data collection, the female researchers (QA and SA) were educated and trained to conduct the THP intervention sessions as well as the pre- and post-intervention interviews. The researchers who conducted the interviews were well-qualified (M.Phil. and PhD degree holders) and had previous experience in qualitative data collection and analysis. The study’s goal and the purpose of the interviews were explained thoroughly to all recruited participants before the data collection process and before the interviewers were introduced.

Following the in-depth interviews conducted during the pre-intervention exploratory phase, the intervention was applied to depressed mothers in the form of psychotherapy sessions through the teaching of coping strategies for stress management during pregnancy. The effectiveness of these strategies was evaluated by conducting in-depth interviews with the same mothers recruited in the pre-intervention phase. Separate semi-structured interview guides were used during the pre- and post-intervention phases that were developed in the light of the themes of four sessions of THP included in the study and were validated by three subject experts (holding doctoral degrees) who were that were unrelated to the study. Further, both the guides were pilot-tested on two participants beforehand, which were not included in the final sample of the study. After informed consent was obtained, interviews were initiated. All the interviews took on average 45 to 60 min and were audio-recorded; additionally, field notes were taken. All pre- and post-intervention interviews (n = 7) were transcribed into the local language (Urdu) before they were translated into English for analysis. As all the women recruited were in the 24–26th week of pregnancy, belonged to lower socio-economic status, similar social contexts and were having the same quality of healthcare (as the women were recruited from a single public health facility), had similar circumstances and experiences, due to which the saturation point was achieved after five interviews during the pre-intervention phase; however, two more interviews were conducted to confirm the saturation point making a total sample of seven participants. During the post-intervention phase, the same participants were interviewed again. Furthermore, to ensure the validity of the data, two repeat interviews were conducted during the pre-and post-intervention phases, and all the transcribed interviews were presented to participants for their comments and corrections.

Data analysis

Pre- and post-intervention interviews were analysed using thematic analysis, following the deductive and inductive approach. This approach was used as it fosters theory generation, flexibility, and a deep understanding of participants’ experiences [16]. First, the collected data were subjected to verbatim transcription in Urdu (the native language) and then translated into English. Second, the researchers went through the process of iterative reading. The transcripts were critically read by the researchers in collective meetings to extract the codes from the data and discuss the data saturation points. In the next stage, many codes related to the broader sociocultural and socioeconomic factors that strongly contribute to developing depression and stress were identified, their management strategies were implemented during the antenatal period, and their effects were explored in the second stage. The final codebook was improved by the compilation of emergent codes and the development of categories in the fourth step, after which initial themes were developed about the factors causing depression and coping strategies that the women found helpful and compelling from psychotherapy sessions. In the last step, the initial themes were reviewed and all researchers approved the final themes. During this step, the findings were also presented to the participants to ensure that the proper meaning was extracted from their quotations. The steps of data analysis are described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design and phases of the study

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Sheikh Zayed Hospital (ID SZMC/IRB/EXTERNAL/PhD/210/2020) and the Ethical Review and Advanced Project Research Board at University of the Punjab (reference D/No 3330). The purpose of the study was explained to the pregnant women, and those who provided written informed consent to participate were included in the research. The confidentiality of the participants was ensured by pseudonymizing the data.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Seven married pregnant women were included in the study. The ages ranged between 22 and 32 years, with an average of 26 years. Nearly half of the patients were primigravida. Many women had educational backgrounds from primary school to postgraduate; however, their male partners had educational backgrounds from middle school to postgraduate. Some women also held prestigious positions in both the public and private sectors. Most of the women shared a joint family system with their in-laws, including mother-in-law, father-in-law, sister-in-law, younger brother-in-law, and older brother-in-law, while few lived in the nuclear family (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

| Participant | Education | Husband’s education | Family structure | Employment status | Income (in PKR) | Parity | Family issues | Housing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Secondary level | Middle | Joint family | Labour | 20,000 | 1 | Husband | Rented house |

| M2 | Postgraduation | Postgraduation | Joint family | Business | > 50,000 | 0 | Mothers in law | Own house |

| M3 | Religious scholar | Graduation | Joint family | Private job | > 50,000 | 0 | Mothers in law | Own house |

| M4 | Postgraduation | Postgraduation | Joint family | Private job | 30,000 | 1 | Mothers in law | Own house |

| M5 | Postgraduation | Postgraduation | Nuclear family | Private job | 30,000 | 3 | Husband | Rented house |

| M6 | High secondary | Postgraduation | Joint family | Private job | 50,000 | 0 | Mothers in law | Own house |

| M7 | Primary | Postgraduation | Joint family | Govt. job | > 50,000 | 3 | Husband | Own house |

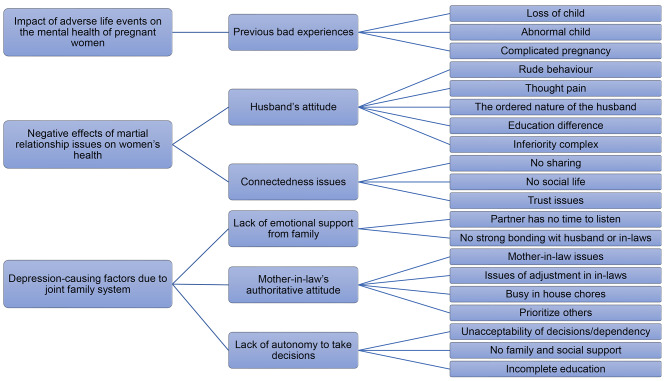

Pre-intervention phase

In the pre-intervention phase of the study, three main themes emerged from the collected data: (1) Impact of adverse life events on the mental health of pregnant women, (2) adverse effects of marital relationship issues on pregnant women’s health, and (3) depression-causing factors due to the joint family system. Figure 2 illustrates the emerged themes, subthemes/categories, and the codes from which the themes are derived.

Fig. 2.

Pre-intervention themes, subthemes, and codes

Impact of adverse life events on the mental health of pregnant women

For many women with depression, pregnancy has proven to be difficult due to their history of traumatic life events. In addition, life events included the death of a child, a divorce from the partner, and a mother’s serious illness, to name a few. The negative thoughts brought about by a negative experience were among the potential AD aggravators. Pregnant women who are in the middle or late stages of pregnancy are more likely to experience depression than postpartum women. Antenatal depression is a devastating condition that can cause a wide range of issues and aftereffects. For instance, depressed pregnant women may deal with a variety of conflicting roles, a lack of social support, uncertainty about the future, emotional instability, and issues with body image. Preterm birth and obstetric complications are additional potential risks.

Additionally, depression in mothers and wives can endanger the mental and physical well-being of newborns as well as their husbands. Different participants shared the adverse life events of their lives that impact their mental health:

“My greatest fear is losing another child. As five years ago, I delivered an abnormal child who could not survive afterwards; I am petrified that it might happen again.” (M1).

“This is my second pregnancy. Last year, I had a miscarriage, and I had a blood pressure problem during pregnancy. That is why I lost my baby.” (M6).

In addition, one participant shared the poor experience of her mentally dysfunctional child:

“I have a 7-year-old mentally disabled child. He cannot eat or urinate himself. He beats his siblings very brutally, which is why I must tie him with a chain. I felt great pain from seeing him in this condition. Many times, the environment of our home gets too stressed.” (M5).

Adverse effects of marital relationship issues on women’s health

Another significant factor identified as contributing to depression in pregnant women was difficulty in relationships. It seems that relationship problems caused by the husband’s or family member’s rudeness and lack of cooperation resulted in symptoms of depression in pregnant women. Due to the emotional highs and lows that pregnancy hormones can cause, many women may feel more vulnerable or anxious. Some women may struggle to manage their symptoms or even experience complications during pregnancy, which can add to extra stress. If pregnant women have a positive relationship with their partners, women who feel loved and supported will better cope with these situations. However, the majority of pregnant women may experience anxiety, depression, or self-doubt due to unhealthy relationships. The majority of the mothers reported that they had to suffer from domestic violence while they were pregnant. Pregnancy could be experienced for the first-time during pregnancy, or preexisting abuse might worsen one’s mental health and pregnancy.

“My husband does not like me and beats me very brutally, even during my pregnancy. When he shouts at me, I tremble with fear, and I cry. He scolds and misbehaves with me all the time.” (M5).

“My husband is very short-tempered and dislikes talking or discussing routine matters. I feel that we lack a friendly relationship. I could not share my problems with him due to fear. He criticises me on different issues and taunts me, blaming my parental family.” (M1).

“I had primary education, and my husband did a master’s degree and had a good Government job. There is a significant difference in education between me and my husband. He does not like me and is not happy with me. I always feel an inferiority complex. He says you are dumb and dull and make dramas; whenever I complain about my bad health and pain, he does not believe me.” (M7).

Depression-causing factors due to the joint family system

Pakistan has a widespread trend of joining families where extended families live together, sharing a typical household environment, household chores, and many other family responsibilities. Usually, the mother-in-law or father-in-law is considered the head of the family, which restricts and interferes with the lives of their son and daughter-in-law. Ultimately, these circumstances create issues for daughters-in-law, for instance, a lack of social support from husbands and families, excessive interference from mothers-in-law, a lack of decision-making capacity from females, and mothers-in-law’s authoritative behaviour.

On the other hand, in a patriarchal society such as Pakistan, household chores are exclusively the domain of women, which also exacerbates the mental condition of pregnant women. This process becomes significantly more difficult for mothers during pregnancy and other difficult times. Some mothers identified stress-inducing factors as the burden of household work and the absence of support from husbands or in-laws. Additionally, women with greater responsibilities and less support from their husbands and families reported sleep problems and fatigue, which harmed their interactions with their husbands and children. Low rewards and lack of visibility in housework are also determining factors for pregnant women.

Therefore, this theme has three subthemes: lack of emotional support from family, mother-in-law’s authoritarian attitude toward a joint family, and lack of autonomy in making decisions.

Lack of emotional support from the family

Another factor that seemed to contribute to the mothers’ depression was a lack of emotional support; when they had nowhere to turn for help, this led to depression. When physical and emotional changes occur during pregnancy, family support and sympathy are crucial, and expectant mothers need kind and caring people close together to share their feelings and struggles. This can help halt the development of depression. An unstable marriage can prevent the wife from discussing her problems with her husband, other family members, or in-laws. Individuals may begin to lack maternal confidence if they do not trust others and do not share their problems with their immediate family. A healthy relationship between partners, family members, and pregnant women is essential for overcoming stress and mood disorders during the transition to parenthood. Women who move to far-off places and different cultures after marriage experience adjustment problems; in such a circumstance, a lack of emotional support results in sadness and depressive symptoms.

“I am unable to discuss my issues with my husband or my mother-in-law. It frustrates me and makes me feel unimportant in the family that I am not even allowed to discuss my problems with my mother because my husband does not like this.” (M2).

“I did not like to share anything with my husband. Whenever I share my mother-in-law’s attitude, my husband always supports his mother and considers me guilty, not in my home even in front of their relatives, which makes me more annoyed. Therefore, I stopped sharing anything with him and did not consider him trustworthy.” (M3).

“I belong to Karachi, and we are married in Lahore. We live in a joint family system. I do not have friends here. I miss my parents and family a lot. I could not visit my parents’ home because it was too far away and required a lot of money and time. I am not frank with my in-laws. Sometimes, I discuss my problems with my sister-in-law, but I cannot discuss many things with her; this makes me feel useless and helpless.” (M4).

Authoritative attitudes of mothers-in-law in joint families

The conflict between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law seems to be a significant source of stress for married women in Pakistan, affecting their psychological health and ability to adjust to marriage and further their period of pregnancy.

The majority of the participants reported that in-laws are a significant cause of depression because of poor behaviour, poor treatment by mothers-in-law during the antepartum period, and lack of support from husbands and family. Increased household responsibilities and a lack of support from the husband and other family members are additional factors that contribute to maternal depression. The family environment significantly impacts the physical and mental health of mothers. More importantly, it appeared that mothers’ poor behaviour directly resulted from husbands’ and mothers’ negative behaviour. Social support was found to be an essential tool for resolving disputes with mothers-in-law. A daughter-in-law may require support from those close to her to deal with the conflict successfully. These support systems could include empathy, a sense of competence, or suggestions for potential resolutions. Positivity may be associated with a daughter-in-law based on how she is viewed by others, either directly or by attenuating the perceived intensity of conflict and psychological well-being.

“My husband is the eldest son of his family and works in a factory; he and I have a significant responsibility at home. We live in a joint family system in a rented house. I was the first daughter-in-law, and my mother-in-law and father-in-law put many restrictions on me; I had no permission to make decisions about my life and family.” (M1).

“My mother-in-law constantly criticises me for her little interest. She creates big issues with minor things. She brainwashes my husband against me, which makes him rude to me. Sometimes I feel I will get mad in such a suffocating environment.” (M2).

This reflects that the family environment is vital to mothers’ physical and mental well-being.

Lack of autonomy in terms of decision

Women do not have the authority or complete freedom to make decisions that affect their own lives, families, or children. They do not receive respect from a family member and frequently rely on their husbands, mothers-in-law, and other relatives to make decisions about their matters. Even when they came to move freely to access medical care and meet basic needs for themselves and their children, women faced restrictions from their husbands and in-laws. Women are prevented from obtaining education and working due to the restrictive and controlled environment created by their in-laws, which causes stress, anxiety, and hopelessness. Mothers’ physical and mental health is impacted by their partners’ harsh and unsupportive attitudes toward their families and children. Females felt frustrated and stressed due to their domestic responsibilities, uncooperative family members, and abuse of power by in-laws, which resulted in antenatal depression.

“I was an MPhil student and had to freeze my semester due to family problems. I have no permission to move independently, even for my gynaecological check-ups. I must wait or request someone to take me to the hospital, which is why I missed some of my routine visits.” (M2).

“My father owns a school, and before marriage, I used to teach there. I still want to continue my job, but my husband does not allow me to teach or do any other job or further studies. I am unhappy with my married life because it greatly restricts me. I cannot continue my studies and teaching when I compare myself with my other sisters and friends; they live joyful lives at university.” (M1).

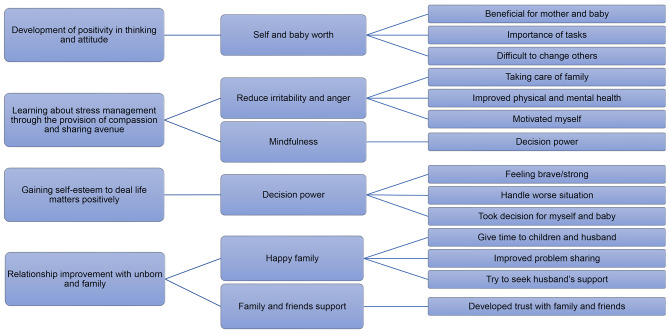

Post-intervention themes

The post-intervention phase focused on THP effectiveness and assessed the intervention’s contribution to reducing depression, as described by the participants. The THP’s objectives were to cure mothers with depression and encourage optimism. Following the postintervention interviews, the four main themes appeared: (1) Development of positivity in thinking and attitude, (2) gaining self-esteem to deal matters positively, (3) relationship improvement with unborn and family, and (4) learning about stress management through the provision of compassion and sharing avenues. Figure 3 represents the themes, subthemes and codes that emerged in the post-intervention phase.

Fig. 3.

Post-intervention themes, subthemes, and codes

Development of positivity in thinking and attitude

Positive thinking concentrates on good things in life and expects good things to occur. Women may find this difficult, particularly during pregnancy. A positive outlook is a way of thinking that does not easily give in and is unaffected by obstacles, problems, or delays. Through the THP intervention, women were inspired to adopt a positive outlook and improve their physical health. THP intervention also aids pregnant women in changing their thought patterns. A mother’s ability to improve her health more effectively will ultimately help to ensure the child’s healthy development. Mothers can be encouraged to stay active by a healthy diet and sufficient sleep. Mothers are unable to adopt healthy habits that are harmful to both the mother and the unborn child because of negative thoughts. Sessions with a psychologist helped pregnant women handle routine tasks or daily life more positively, which ultimately seemed beneficial for the mother. Positive thinking, which is related to the mother’s physical and mental well-being, appears crucial for a healthy baby’s sake.

“Before sessions with a psychologist, I used to find faults in my thinking behaviour, which made me irritable and angry. I realised that we can do everything when we prioritise things for ourselves and our children. I averted my negative for me and my unborn baby. I feel much better about myself. I stopped overthinking about my mother-in-law’s behaviour; it improved my irritating behaviour and anger.” (M2).

“My previous practices during pregnancy were not good. I was not eating three meals and never asked for help or discussed my needs with anyone. I used to take my breakfast with my husband and wait until night to have dinner with him or with family. However, now, I started to eat my diet correctly. After seven years, I conceived and tried my best to perform all the practices to get a healthy and normal child. That motivated me a lot to take care of myself and my baby.” (M1).

Learning about stress management through the provision of compassion and sharing avenue

Stress management is a psychological intervention technique that reduces how the body responds to demanding environmental circumstances. These troubling responses could be the result of negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger, pain, or illness. The intervention helped the mothers by directing ways of reducing discomfort, which may include directly addressing the source of the stress through relaxation, altering one’s perspective of the situation (reappraisal), or changing the environment (e.g., making greater use of available social support). THP sessions assisted pregnant women in managing stress and opening up to share their issues rather than enduring them silently. Women who have learned stress-coping techniques attempt to control their problems by looking for solutions rather than thinking negatively about them. The meetings also gave them a sense of community and gave them a place to talk about their issues. Pregnant women find relief and relaxation from negative thinking by spending time with someone, talking about the positive aspects of life, and exploring solutions to the issues and difficulties of parenthood.

“I liked the way you counselled me about my mentally retorted child, and I felt relaxed knowing that there is someone who understands my difficulties and I am not facing them alone. These sessions motivated me to take care of myself and my unborn baby.” (M5).

“I decided to participate in the program for my mental relaxation. I did not share my problems with anyone. I was harming myself physically and mentally. You listened to all my concerns very carefully and made me very relaxed. I avoid overthinking useless things now. When I did not react to small things, my home environment automatically went well, and my mood also improved.” (M2).

Gaining self-esteem to deal life matters positively

People who are confident in themselves and their abilities appear at ease. They engender confidence and invite others to trust. All of these qualities are desirable to possess. However, it is not always simple to have self-confidence, especially if you tend to be critical of yourself or if other people criticise you. Almost all mothers asserted that every aspect of our lives requires self-confidence, but many people lack it. The THP intervention revived and boosted our self-confidence to address life matters positively and more efficiently.

“My mother is blind, and my elder sister also had a 3rd trimester of pregnancy. My mother-in-law also refused to take care of me. After delivery, I was alone in the hospital and had a C-section, and my husband was also not allowed to come there. I was terrified. I changed a lot. If I were my previous self, I would die, weeping and crying, and I could not manage the things that I could be able to do at this time.” (M2).

“In my opinion, I became brave now and gained some self-confidence in facing and handling the worst situation. I will be affectionate toward my children and develop a strong bond with them. I managed a helping hand to support me these days by discussing my situation with my husband and neighbourhood friend.” (M5).

“Can you believe I sold my gold set a couple of weeks ago? My husband tried to convince me to sell many times, but I refused. Through these sessions, I converted my thoughts from negative to positive and gave them to my husband without any bad behaviour. That was very unusual for my husband and my in-laws. This was very relaxing for me because it solved our problem, which can give me stress.” (M4).

Relationship improvement with the unborn child and family

One of the key focuses of these psychotherapy sessions, which were shared by some of the participants, was building relationships with the unborn individual and other family members that gave the mother a comforting feeling and a sense of connection. A woman’s life goes through a new stage with pregnancy, along with all the changes that may result from that new stage. People often discuss obvious factors, such as cravings, exhaustion, nausea, and body shape. Still, other circumstances, such as negotiating new employment terms and reorganising your finances, can make this a challenging time. Many women experience emotional, financial, physical, and social changes during pregnancy. A normal and important aspect of getting ready to have children is experiencing mixed emotions. Women’s relationships undergo significant changes because of their pregnancy, particularly if the pregnancy is the first child. While some women adjust to these changes without much difficulty, others struggle. It is quite typical for couples to argue while pregnant occasionally. It is crucial to understand that there are valid reasons for feeling closer and more in love during pregnancy and for occasional difficulty. The mother’s positive behaviour seemed to depend on her family’s ability to form a strong bond with her. Strengthening a mother’s bonds with her child and other family members can be facilitated by practising conflict resolution and problem-solving techniques.

“I am taking care of my diet all the time for my baby. I feel much better about myself and my well-being. I tried to develop a good relationship with my husband and in-laws. When I started practising developing a bond with the unborn child, it responded to me by giving me movements. My relationship with a 3-year-old child has also improved. I loved him more, tried to spend time with him, and enjoyed his playing activities, which relaxed me.” (M4).

“My husband was not cooperative, which made me so angry. However, now I have changed my thinking and found that he did so because he thought all these activities made me active and engaged with him. He made me realise I am not ill and I can do house chores. The development of relations with the unborn was fascinating for me. I feel my baby with love; I talk to him in my imagination, and he responds to me by making movements. This is my very pleasurable activity.” (M2).

Discussion

The overarching findings of this study revealed several themes and subthemes, which were divided into pre- and postintervention stages; some of them are unique to the sociocultural setting of Pakistan, but others are already known in the literature.

The impact of adverse life events on the mental health of pregnant women was identified as one of the significant causes of depression. This was interpreted in different ways, such as fear of losing a child or having another abnormal baby. This leads to AD in women who belong to families with low socioeconomic status. Furthermore, a lack of family support has also been identified by other researchers [17]. Suppose proper and timely psychological support is not provided: in that case, women are at greater risk of experiencing depression during pregnancy and later in the postpartum period [18], which is consistent with findings of previous studies [6, 9, 19]. Further, another qualitative study conducted in Pakistan has also identified women disempowerment as factor leading to anxiety and stress among pregnant women [20]. The current study showed that a lack of social support from family prevented women from sharing their daily life problems, which was another major cause of antenatal depression in women. The THP intervention was a similar platform that helped women share their concerns and fears; this would have been done in family settings with little help and little awareness.

Furthermore, in the Pakistani cultural context, in joint or extended family structures, lower social support from husbands, children and mothers-in-law is significantly associated with depression in the third trimester of pregnancy [20, 21]. The joint family system is considered a vital family setting in traditional societies that provides opportunities to live together by supporting each other rather than suffering alone. However, in this study, women felt neglected and less empowered. It was also noted that antenatal depression was more prevalent in women who lived in traditional joint families and had more family members [22].

Another cause of AD among pregnant women was relationship problems with their husbands; however, these problems were not as severe as those reported in earlier studies, such as domestic violence, physical and verbal abuse and humiliation [6, 9, 19]. Like the findings of the present study, community-based research revealed that intimate partner violence was reported by one out of every fifth pregnant mother and was directly associated with antenatal depression [7]. In addition, a study reported that 14% of women were affected by antenatal depression, while more than 15% of women experienced any form of intimate partner violence [23].

Keeping in sight Pakistan’s cultural and social context, out of sixteen, four sessions of THP were used in the intervention phase. The postintervention interviews resulted in the emergence of four themes that were found to be the critical dimensions for alleviating depression in women. These include developing positive thinking and attitudes, learning about stress management through providing compassion and sharing avenues, gaining self-esteem to address matters positively and improving relationships with the unborn child and family. The women included in the study reported the positive impacts of THP in alleviating depression and stress management, like in a previous study [12]. The present study’s THP intervention helped women revive their social and emotional support. They were encouraged to develop good social relationships with their husbands, family, friends, and neighbours to share problems and ask for help in emergencies to prevent the worst outcome. Likewise, another qualitative study has also reported strengthening social relationships in addition to believing in oneself, optimistic approach, dealing with emotions, identifying purpose of life and spirituality as the main coping strategies for promoting prenatal mental health [24]. Similarly, this intervention has been proven effective in helping women revive their self-confidence and manage depression by assisting them to understand that stress during pregnancy is normal and that women need only some stress management techniques to live healthy lives.

To avoid maternal depression or other psychological and physical illnesses, it is essential to provide psychological help before, after, and during pregnancy to battered and abused women [25]. Some techniques are straightforward and can be used by laypersons with little training or assistance. The selected THP techniques used in this study can be taught at the community level and used to provide relief to depressed women during pregnancy.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. First, the study was designed and conducted purely in the sociocultural context of Pakistan, which limits its generalizability to other settings having varying cultural underpinnings and socio-demographic characteristics. Future studies on local, provincial and national level as well as in the context of other socio-cultural settings are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the THP.

The strength of our research is that the present study is one of its kinds of studies that incorporate qualitative methods into a quasi-experimental design to obtain an in-depth understanding of the factors responsible for depression among pregnant women.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that depression during pregnancy is a serious problem among women for diverse cultural and personal reasons. Although the findings of the present study explored the usefulness of THP and found it as a valuable tool for helping many pregnant women who are experiencing prenatal depression recover, there is a need to further explore the benefits of THP in varying socio-cultural contexts. Numerous pregnant women praised the THP project and recommended that hospitals should adopt it to assist pregnant patients in the Pakistani health system. In future, these evidence-based interventions need to be implemented by engaging healthcare units and local communities in different cultural contexts to further understand their role in alleviating the maternal mortality rate and the worsening health outcomes faced by mothers and children in Pakistan.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and staff of Sheikh Zayed Hospital, Lahore and the University of Punjab Lahore.

Abbreviations

- AD

Antenatal depression

- CBT

Cognitive behaviour therapy

- LMIC

Lower-middle-income country

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Care Questionnaire-9

- THP

Thinking Healthy Programme

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

The study was conceptualized by JS, MI, RZ and RS. QA was responsible for data curation and formal analysis. JS, MI, RZ and FF supported in data curation; MI and SA were involved in formal analysis. JS had a major role in validation and supervision. QA and SA prepared the original draft of the manuscript; JS, RZ, RS, SMK and FF revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Sheikh Zayed Hospital (ID SZMC/IRB/EXTERNAL/PhD/210/2020) and the Ethical Review and Advanced Project Research Board at the University of the Punjab (reference D/No 3330). The purpose of the study was explained to pregnant mothers, and those who provided written informed consent to participate were included.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Insan N, Forrest S, Jaigirdar A, Islam R, Rankin J. Social determinants and prevalence of antenatal depression among women in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin X, Sun N, Jiang N, Xu X, Gan Y, Zhang J, Qiu L, Yang C, Shi X, Chang J, Gong Y. Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;83:101932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyatt S, Ostbye T, De Silva V, Long Q. Antenatal depression in Sri Lanka: a qualitative study of public health midwives’ views and practices. Reprod Health. 2022;19:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith A, Twynstra J, Seabrook JA. Antenatal depression and offspring health outcomes. Obstet Med. 2020;13(2):55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghimire U, Papabathini SS, Kawuki J, Obore N, Musa TH. Depression during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight, preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction-an updated meta-analysis. Early Hum Dev. 2021;152:105243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atif M, Halaki M, Raynes-Greenow C, Chow CM. Perinatal depression in Pakistan: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Birth. 2021;48(2):149–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belay S, Astatkie A, Emmelin M, Hinderaker SG. Intimate partner violence and maternal depression during pregnancy: a community-based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0220003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishtiaque S, Sultana S, Malik U, Yaqoob U, Hussain S. Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Karachi, Pakistan. Rawal Med J. 2020;45(2):434. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan R, Waqas A, Mustehsan ZH, Khan AS, Sikander S, Ahmad I, Jamil A, Sharif M, Bilal S, Zulfiqar S, Bibi A, Rahman A. Predictors of prenatal depression: cross-sectional study in rural Pakistan. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:584287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omer S, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. The influence of social and cultural practices on maternal mortality: a qualitative study from South Punjab, Pakistan. Reprod Health. 2021;18:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bright KS, Norris JM, Letourneau NL, King Rosario M, Premji SS. Prenatal maternal anxiety in South Asia: a rapid best-fit framework synthesis. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuhr DC, Weobong B, Lazarus A, Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, Singla DR, Tabana H, Afonso E, De Sa A, D’Souza E, Joshi A. Delivering the thinking healthy Programme for perinatal depression through peers: an individually randomised controlled trial in India. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(2):115–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikander S, Ahmad I, Atif N, Zaidi A, Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, Nisar A, Tabana H, Ain QU, Bibi A, Bilal S. Delivering the thinking healthy Programme for perinatal depression through volunteer peers: a cluster randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(2):128–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eappen BS, Aguilar M, Ramos K, Contreras C, Prom MC, Scorza P, Gelaye B, Rondon M, Raviola G, Galea JT. Preparing to launch the ‘Thinking healthy Programme’ perinatal depression intervention in Urban Lima, Peru: experiences from the field. Glob Ment Health. 2018;5:e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher J, Nguyen H, Mannava P, Tran H, Dam T, Tran H, Tran T, Durrant K, Rahman A, Luchters S. Translation, cultural adaptation and field-testing of the thinking healthy program for Vietnam. Global Health. 2014;10:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter D, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. J Nurs Health Care. 2019;4(1).

- 17.Waqas A, Raza N, Lodhi HW, Muhammad Z, Jamal M, Rehman A. Psychosocial factors of antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan: is social support a mediator? PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazi A, Fatmi Z, Hatcher J, Kadir MM, Niaz U, Wasserman GA. Social environment and depression among pregnant women in urban areas of Pakistan: importance of social relations. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(6):1466–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowther AA, Kazi AK, Nazir H, Atiq M, Atif N, Rauf N, Malik A, Surkan PJ. A woman is a puppet. Women’s disempowerment and prenatal anxiety in Pakistan: a qualitative study of sources, mitigators, and coping strategies for anxiety in pregnancy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senturk V, Abas M, Berksun O, Stewart R. Social support and antenatal depression in extended and nuclear family environments in Turkey: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahsan Q, Hassan J, Akhtar T, Khan A, Malik A. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors during 2nd wave of COVID-19 among pregnant women in a tertiary hospital. Lahore Humanit Social Sci Reviews. 2021;9(3):846–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melby TC, Sørensen NB, Henriksen L, Lukasse M, Flaathen EM. Antenatal depression and the association of intimate partner violence among a culturally diverse population in southeastern Norway: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Midwifery. 2022;6:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhamani SS, Arthur D, Van Parys AS, Letourneau N, Wagnild G, Premji SS, Asad N, Degomme O. Resilience and prenatal mental health in Pakistan: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;;22:839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Mazza M, Caroppo E, Marano G, Chieffo D, Moccia L, Janiri D, Rinaldi L, Janiri L, Sani G. Caring for mothers: a narrative review on interpersonal violence and peripartum mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.