Abstract

Background

Recent studies have indicated that coffee consumption is inversely correlated with sarcopenia in the elderly population. Data regarding the association between caffeine intake and muscle mass in young adults are scarce.

Objective

We aimed to investigate how dietary caffeine correlates with muscle mass and sarcopenia in the young and middle-aged people.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study utilizing data from NHANES. Muscle mass was evaluated using DXA and caffeine intake was derived from 24-h dietary recalls. Multivariable regression analysis was adopted to explore association between caffeine and sarcopenia. Restricted cubic spline analysis was conducted to investigate dose-response effect of dietary caffeine on muscle mass. Mediation effect of high-sensitivity C reactive protein was examined by mediation analysis.

Results

A total of 9116 adults aged from 20 to 59 years old were included. Higher ingestion of caffeine was not associated with sarcopenia. Association between dietary caffeine and muscle mass was found to be W-shaped in males and U-shaped in young females, wherein mediation effect of hs-CRP was not discovered.

Conclusions

Caffeine consumption is associated with muscle mass in a nonlinear pattern. ASMI peaks at a daily caffeine intake of 1.23 mg/kg in young adults, while 0.64–1.49 mg/kg is recommended for middle-aged men.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12891-024-08063-z.

Keywords: Caffeine, Muscle mass, Sarcopenia, NHANES

Introduction

Sarcopenia is commonly deemed as an aging-related process with excessively accelerated loss in muscle quantity and quality, and also associated with numerous adverse outcomes, including falls, physical disabilities, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [1–3]. It is estimated that individual’s skeletal muscle mass usually peaks at the age of 40 [4]. Once an individual reaches 50s, the muscle mass progressively decline off 1–2% yearly [5]. However, sarcopenia never is a geriatrics-only disorder and can take place in early adulthood, which poses an even more long-standing detriment to health [6]. Risk factors towards muscle decline, including genetic backgrounds, malnutrition, lifestyle behaviors and contemporaneous diseases across lifespan have been established [1, 7]. Although clinical and experimental trials are currently ongoing, no effective pharmacological approaches are available for the treatment [8–11]. Thus, an effort should be initiated earlier in order to reach a maximal muscle mass, postpone its decline to prevent sarcopenia.

Coffee, abundant with caffeine and multiple bioactive polyphenols, is the most prevalent beverage worldwide. Ingestion of two to four regular cups of coffee provides the equivalent of 3–6 mg/kg of caffeine, which has been proven to enhance sports performance and muscular strength [12–14]. As a popular ergogenic and psychoactive substance, caffeine consumption has also captured the interests of researchers in terms of its influence on overall health, driven by its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effect. For instance, caffeine may improve Parkinson’s disease, cognitive performance and depression [15–17]. Increases in caffeine intake is associated with favorable body composition change, glucose and lipid metabolism, alleviated liver steatosis and fibrosis, decreased risk in hepatic carcinoma [18–22]. Epidemiological evidences also indicate that coffee may reduce death from cardiovascular causes and all-cause mortality [23–26]. We assume that caffeine, but not other ingredients within coffee, is positively associated with muscle mass and may prevent or delay the development of sarcopenia among young adults.

Existing knowledge of coffee consumption on skeletal muscle and its relationship with sarcopenia is limited and mainly restricted to older adults [27, 28]. Whether it is the caffeine or other components inside coffee that affects muscular system is currently indeterminate. Herein, we aim to investigate the association of dietary caffeine intake with sarcopenia and explore its dose-response relationship with muscle mass in US adults.

Methods

Study population

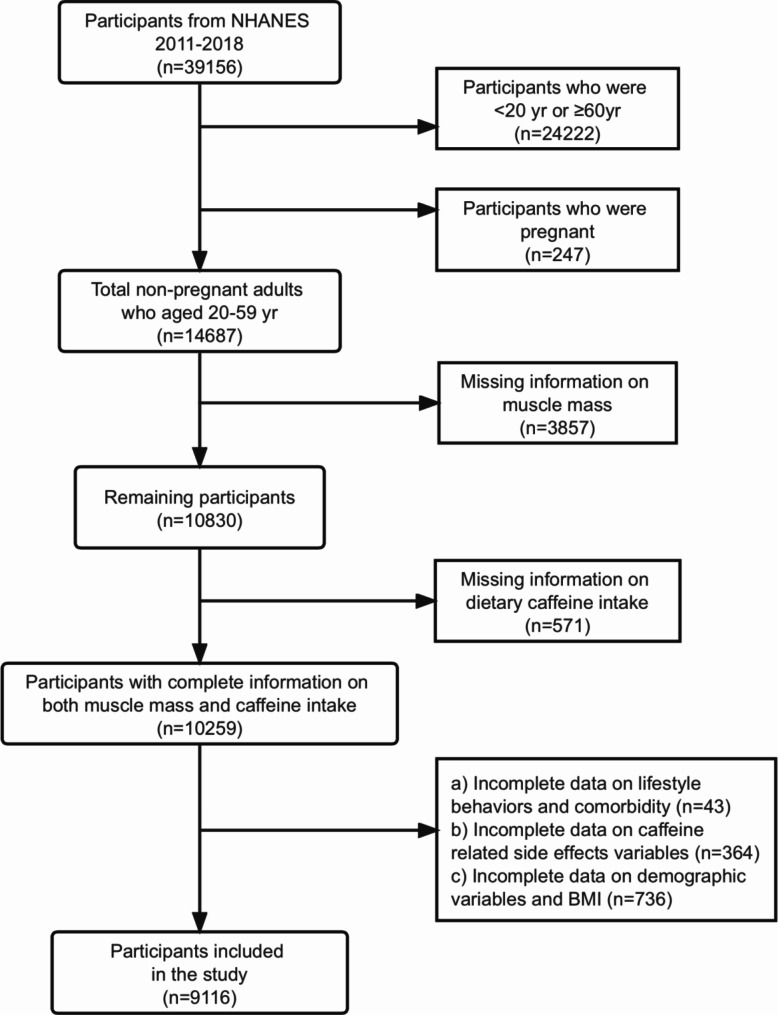

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database is a freely accessible database with information from a continuously collected, cross-sectional survey of non-institutionalized civilian residents of the United States. Interview, physical examination, laboratory data are included in the dataset and can be downloaded from the website. A total of 39,156 participants from 2011 to 2018 were screened. We screened those who were 20–59 years old and not pregnant (n = 14687). We excluded those with missing information on muscle mass (n = 3857). Participants without data on dietary caffeine intake were also excluded (n = 571). Those who had incomplete data on other important variables such as demographic factors, lifestyle behaviors, comorbidity and side-effects related variables were further excluded (n = 815). Finally, 9116 adults (4526 males and 4590 females) were eligible for the study, as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the included participants

Assessment of sarcopenia and muscle mass

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is a widely used and non-invasive instrument to determine individual’s body composition, i.e., lean tissue, fat tissue mass, and bone mineral density. Muscle mass is generally related to body size. Thus the absolute amount of lean mass of both right and left arms and legs, was adjusted for height squared (ASM/height2), namely appendicular skeletal muscle mass index (ASMI). Sarcopenia was then diagnosed according to EWGSOP2 criteria cut-off points, that is, an ASMI less than 7.0 kg/m2 for men or 5.5 kg/m2 for women [4].

Assessment of daily caffeine and nutrition intake

Daily caffeine intake was standardized by body weight. If an individual completed both 24-h dietary recalls, we used the average caffeine intake from the two recalls. Otherwise, we used the data from the first 24-h dietary recall. Similarly, same method was employed to calculate other essential dietary nutrients, including total calories, nutrients intake and alcohol consumption.

Covariates ascertainment

Variables including sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race, education level, ratio of family income to poverty), anthropometric parameters mainly body mass index (BMI), behavioral factors such as cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and chronic comorbidity were extracted from the database.

Participants were classified into young adults and middle-aged adults according to a cutoff age of 40. Ethnicity groups were comprised of Mexican American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black and Other Race. Educational level was divided into three categories. Smoking status was derived from questionnaire SMQ. Alcohol drinking status was confirmed using 24-h dietary recalls. Physical activity was illustrated as total minutes on moderate and vigorous intensity recreational activities per week. Time on sedentary activity in a typical day was derived from questionnaire PAQ. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, arthritis, stroke event, tumor history, medical history in terms of heart, lung, liver or kidney disease were based on BPQ, DIQ, glucolipid metabolism profiles, blood pressure documented in the mobile examination center, MCQ and KIQ. Participants who had any of these diseases were classified as having a comorbidity. In terms of potential side effects of caffeine, SLQ, pulse rate and total bone mineral density (BMD) evaluated by DXA were further extracted from the database. High-sensitivity C reactive protein (hs-CRP) level, though only detected in two cycles, was also included to explore purported mediation effect. Detailed explanations were presented in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

The NHANES sampling weights were considered in the complex sample analyses by “survey” package to achieve nationally representative estimates. Basic characteristics were presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables, and frequencies (proportions) for categorical variables. Descriptive analyses by both genders and caffeine intake quartile were performed, and differences in characteristics were compared using Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA or Chi-squared tests accordingly. We first performed univariable logistic regression analyses to identify potential confounders. Complex sample multivariable logistic regression analyses were further introduced to investigate the association between caffeine intake and the risk of sarcopenia, with the lowest quartile selected as a reference. Model 1 was adjusted for gender and age; Model 2 was further adjusted for ethnicity and PIR; Model 3 was additionally adjusted for lifestyle factors. Dietary nutrition including energy, protein, fat, carbohydrate, sugar, vitamin D and comorbidity status were lastly fitted in the fully adjusted Model 4. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses with four knots adjusted for all covariates were conveyed to further explore possible dose-response effect. Due to muscle mass intrinsically varied between sex and age, the RCS analyses were also preformed stratified by gender and age groups. Finally, “Mediation” package was used to explore putative mediation role of hs-CRP in the link between dietary caffeine intake and muscle mass. Participants who had hs-CRP level tested and those not were also compared to avoid skewed results.

All hypothesis tests were two sided. Significance was defined at α = 0.05 level. Analyses were performed using R, version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with R Studio, version 2022.07.1 Build 554 (R Studio Inc).

Results

Characteristics of participants stratified by gender

Basic characteristics of the included participants were shown in Table 1. Female adults had a higher prevalence of sarcopenia (11% vs. 7%, P < 0.0001) and a lower ASMI (7.01 ± 1.42 vs. 8.90 ± 1.38, P < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in dietary caffeine intake between genders. Compared to male participants, female citizens were older and had higher educational attainment. Male participants were more physically active but more prone to hypertension and other unfavorable behaviors, including cigarette and alcohol consumption. Men had more dietary energy and food intake, mainly carbohydrates, protein, total fat, sugar and vitamin D, than women participants.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the participants by gender from NHANES 2011–2018

| Variables | Overall (N = 9116) |

Male (n = 4526) |

Female (n = 4590) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 39.20 ± 11.87 | 38.70 ± 11.88 | 39.72 ± 11.84 | 0.0078 |

| Ethnicity | 0.4401 | |||

| Mexican American | 1319 (10.5%) | 651 (11.0%) | 668 (10.0%) | |

| Other Hispanic | 909 (7.0%) | 421 (7.0%) | 488 (6.9%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3348 (61.6%) | 1660 (60.9%) | 1688 (62.2%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1854 (10.8%) | 918 (10.9%) | 936 (10.7%) | |

| Other Race | 1686 (10.1%) | 876 (10.2%) | 810 (10.1%) | |

| Education level | < 0.0001 | |||

| below college | 3506 (33.8%) | 1933 (37.9%) | 1573 (29.6%) | |

| some college | 3039 (33.9%) | 1382 (32.0%) | 1657 (35.8%) | |

| college graduate or above | 2571 (32.3%) | 1211 (30.0%) | 1360 (34.7%) | |

| PIR | 2.92 ± 1.68 | 2.95 ± 1.67 | 2.88 ± 1.70 | 0.0999 |

| Caffeine intake (mg/kg) | 2.05 ± 2.44 | 2.00 ± 2.33 | 2.09 ± 2.54 | 0.2091 |

| Sarcopenia | 847 (9.0%) | 322 (7.0%) | 525 (11.0%) | < 0.0001 |

| ASMI (kg/m^2) | 7.96 ± 1.69 | 8.90 ± 1.38 | 7.01 ± 1.42 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m^2) | 28.67 ± 6.60 | 28.52 ± 5.78 | 28.83 ± 7.34 | 0.1082 |

| Lifestyle behaviors | ||||

| recreational exercise time (min) | 190.57 ± 298.00 | 217.11 ± 339.78 | 163.73 ± 245.85 | < 0.0001 |

| time on sedentary behaviors (min) | 385.61 ± 204.18 | 384.44 ± 204.95 | 386.78 ± 203.40 | 0.7223 |

| cigarette smoking | < 0.0001 | |||

| non-smoker | 5505 (58.5%) | 2419 (53.7%) | 3086 (63.3%) | |

| former smoker | 1553 (19.7%) | 911 (22.7%) | 642 (16.6%) | |

| current smoker | 2058 (21.8%) | 1196 (23.6%) | 862 (20.1%) | |

| heavy alcohol drinker (%) | 1760 (22.7%) | 982 (24.2%) | 778 (21.1%) | 0.0229 |

| Dietary factors | ||||

| energy (kcal/kg) | 27.70 ± 12.49 | 29.82 ± 13.15 | 25.56 ± 11.40 | < 0.0001 |

| protein (g/kg) | 1.08 ± 0.52 | 1.18 ± 0.56 | 0.99 ± 0.46 | < 0.0001 |

| fat (g/kg) | 1.07 ± 0.55 | 1.14 ± 0.59 | 1.00 ± 0.51 | < 0.0001 |

| carbohydrate (g/kg) | 3.27 ± 1.64 | 3.47 ± 1.70 | 3.07 ± 1.55 | < 0.0001 |

| sugar (g/kg) | 1.41 ± 0.95 | 1.47 ± 0.99 | 1.35 ± 0.91 | 0.0003 |

| vitamin D (mcg/kg) | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.06 | 0.0029 |

| Comorbidity status | ||||

| had comorbidity (%) | 6857 (74.8%) | 3397 (75.1%) | 3460 (74.5%) | 0.6482 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 961 (8.0%) | 492 (8.6%) | 469 (7.5%) | 0.1609 |

| Hypertension (%) | 2582 (27.0%) | 1355 (30.1%) | 1227 (23.7%) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 5835 (64.2%) | 2869 (63.7%) | 2966 (64.6%) | 0.6179 |

For continuous variables, data were presented as weighted mean ± SD, and P value was estimated using Student’s t-test; For categorical variables, data were presented as actual number (weighted proportion%), and significance was tested using the Chi-squared tests

Comparisons of characteristics and side effects by caffeine intake

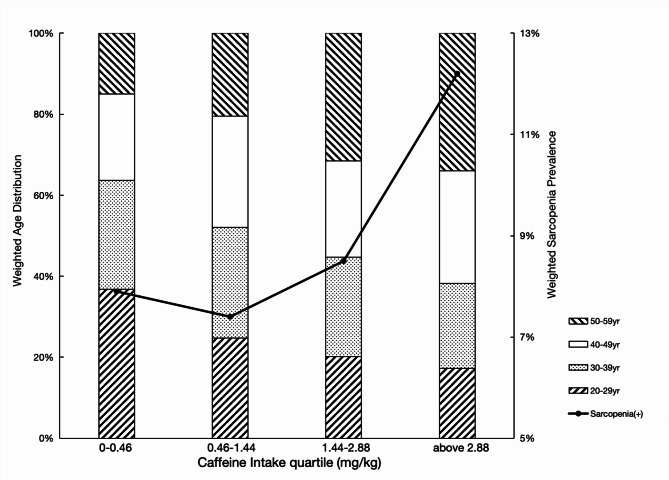

Weighed sarcopenia prevalence and age distribution by caffeine intake quartile were depicted in Fig. 2. Compared to those who were in the lowest quartile (< 0.46 mg/kg), participants in the highest quartile (≥ 2.88 mg/kg) were more subjected to sarcopenia (12.2% vs. 7.9%, P = 0.0003) and had a smaller ASMI (7.54 ± 1.54 vs. 8.26 ± 1.81, P < 0.0001). However, the proportion of middle-aged adults (aged more than 40 year) was also higher in accordance to the increment of dietary caffeine intake. Participants with higher caffeine intake were more incline to have trouble sleeping and a lower BMD. Detailed comparisons of characteristics and possible adverse side effects were presented in Table S2 and Table S3.

Fig. 2.

Graphic presentation of weighted age distribution and weighted sarcopenia by caffeine intake

Association between dietary caffeine intake quartile and sarcopenia

Results of survey univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis were given in Table S4 and Table 2, respectively. Participants who consumed more caffeine had a higher risk for sarcopenia after adjusting for demographic factors (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.02–1.07, P = 0.005, P for trend = 0.001). However, this association disappeared in fully adjusted model.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses for Sarcopenia

| Caffeine intake | P value | P for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |||

| Crude model | Ref. | 1(0.97, 1.02) | 1.01(0.99, 1.03) | 1.04(1.02, 1.07) | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Model 1 | Ref. | 1(0.98, 1.02) | 1.01(0.99, 1.03) | 1.06(1.03, 1.08) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | Ref. | 1(0.98, 1.02) | 1.01(0.99, 1.03) | 1.04(1.02, 1.07) | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| Model 3 | Ref. | 1(0.98, 1.02) | 0.98(0.97, 1) | 0.99(0.97, 1.02) | 0.4 | |

| Model 4 | Ref. | 1(0.98, 1.02) | 0.98(0.96, 1) | 0.99(0.96, 1.01) | 0.2 | |

Model 1: adjusted for gender, age; Model 2: adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, PIR; Model 3: adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, PIR, BMI, smoking, alcohol, physical exercise time; Model 4: adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, PIR, BMI, smoking, alcohol, physical exercise time, dietary factors and comorbidity

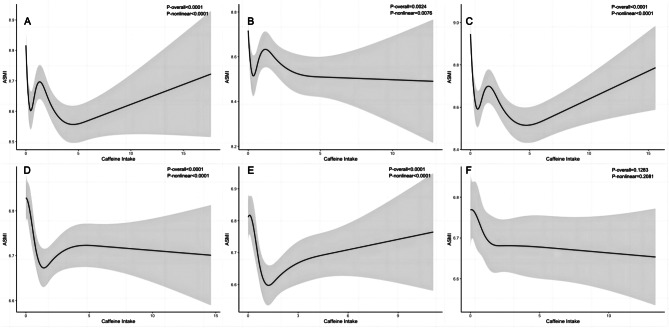

Nonlinear association between caffeine intake and muscle mass

We further testified possible nonlinear relationship between dietary caffeine intake and muscle mass, both as continuous variables, using restricted cubic spline analyses adjusting for all covariates. As shown in Fig. 3, there was a nonlinear correlation between ASMI and caffeine intake in middle-aged male adults (P < 0.0001, P nonlinear < 0.0001), young males (P = 0.0024, P nonlinear = 0.0076) and young females (P < 0.0001, P nonlinear < 0.0001). Detailed cutoff points of caffeine intake and corresponding muscle mass, either maximal or minimal, were presented in Table S5. There was a W-shaped downward trend in male participants. Among middle-aged male participants, ASMI reaches at 8.70 kg/m2 when taking caffeine at 1.49 mg/kg. The threshold caffeine value for a high ASMI in young males is 1.23 mg/kg. A U-shaped curve was identified in females aged 20–39 year, indicating an upward trend in muscle mass when caffeine consumption reached at 1.23 mg/kg. There was no statistically significant association in women aged more than 40 year (P = 0.1283, P nonlinear = 0.2081). No mediator effect of hs-CRP was found (ACEM: P = 0.682 in men; P = 0.236 in women), as demonstrated in Figure S1.

Fig. 3.

Dose response relationship between ASMI and caffeine intake (A: overall male; B: young male; C: middle-aged male; D: overall female; E: young female; F: middle-aged female). Model was adjusted for age, ethnicity, PIR, BMI, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical exercise time, dietary factors and comorbidity status

Discussion

To our best knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the association between dietary caffeine intake with muscle mass and sarcopenia in nonelderly people. Nonlinear relationship between caffeine intake and muscle quantity is noticed in young and middle-aged men and young female participants, which high-sensitivity C reactive protein poses no mediation effect on. However, caffeine intake is not associated with sarcopenia after adjusting for multiple covariates.

Accumulating evidences supported an inverse link between self-reported coffee consumption and sarcopenia. Lee DY et al. insisted that elderly individuals who consumed fewer than one cup of coffee per day had a greater risk of sarcopenia than those who drank more than three [28]. Another study found sarcopenia prevalence was lower in men who drink coffee, but not in women [29]. Evidences from Japanese middle-aged and older population showed a significant positive association between coffee intake and SMI, evaluated by a BIA method [27, 30]. However, coffee is a complex matrix of numerous constituents but not simply synonymous with caffeine, which has not been accurately measured in aforementioned studies. Besides, existing data are merely from East Asian middle-aged and elderly population, evidences from a younger generation are scarce.

Here in our study, the association between dietary caffeine and sarcopenia did not reach a statistical significance after we introducing several lifestyle traits such as time of recreational physical activities, alcohol and smoking habits or other dietary factors. Meanwhile we adopted the EWGSOP2 criteria in this study, due to a vacancy in the diagnosis of sarcopenia for young people. We therefore hypothesized this null relationship could be explained as follows i). the impact of those lifestyle traits outweighs that of caffeine, ii). the less stringent diagnosis criteria may underscore the importance of caffeine, iii). adults aged 20–59 year are barely mainstream population for sarcopenia, potentially leading to a selection bias in the first place, iv). similarly, up to 90% of the study participants were non-Asians, who are relatively not subjected to sarcopenia [1], v). people from Western cultures habitually consume more caffeine, also served as a non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist [31], which might induce a receptor tolerance through a long-term caffeine intake [32].

Metabolites of caffeine are mainly generated in the liver and then excreted in the urine [33]. Approximately 84% of ingested caffeine is metabolized into paraxanthine [33]. It has been reported that paraxanthine supplementation increases muscle mass in mice [34, 35]. Other purported mechanisms underlying protective effects of caffeine on muscle quantity are mainly attributed to i). its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [36], since it is recognized that oxidative stress takes part in the progression of muscle decline; ii) enhancement in the cell proliferation rate and DNA synthesis, leading to muscle hypertrophy; iii) activation of intracellular Akt signaling pathway in satellite muscle cells and anabolic signals [37, 38].

Caffeine of excessive doses in fact might reverse potential benefits. For instance, current studies have demonstrated a nonlinear relationship between caffeine and muscle performance, metabolic disorders or other diseases [39–41]. However, potential dose-response association of caffeine with muscle mass has rarely been elucidated. We have found the increment of caffeine intake is nonlinearly related to ASMI, exhibiting a W-shaped fluctuating downward trend in male participants, but following a U-shaped curve among female young adults. Among middle-aged male participants, ASMI reaches at 8.70 kg/m2 when taking caffeine at 1.49 mg/kg. The threshold caffeine value for a high ASMI in young males is 1.23 mg/kg. In females aged 20–39 year, there is a gradual upward trend in muscle mass when caffeine consumption is above 1.23 mg/kg. As for middle-aged females, no association between caffeine ingestion and muscle mass has been observed. The CYP1A2 gene determines the rate of caffeine metabolism, and a clear variation in individual responses to caffeine ingestion exists, which might partly account for the non-linearity of the beneficial effects [42]. The ACTN3 gene encodes α-actinin-3, which is a protein expressed in fast-twitch muscle fibers. It has been suggested that tea and coffee related skeletal muscle benefits may be contingent upon ACTN3 genotype and sex difference [43]. In addition, different nonlinear patterns are also observed between age and gender subpopulations. We speculate that it could be due to the impact of sexual hormone changes outweighs that of caffeine intake across this transitional period. The skeletal muscle is the predominant tissue in which sex hormone receptors are located [44]. Either estrogen or testosterone deficiency can induce myosin dysfunction and hinder muscle regeneration, consequently leading to lower quantity and quality in muscle [45]. Caffeine has been suggested to affect bone through derangement of calcium metabolism, alteration of vitamin D responses, and regulation of osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation [46, 47]. Excessive ingestion of caffeine is associated with a decline in bone mineral density, which possibly overturns its benefits in muscle mass [48, 49]. To sum it up, the nonlinear association indicates that the impact of caffeine on the synthesis and catabolism balance of skeletal muscle is complex and ovonic. Further researches are warranted to illustrate its potential mechanisms.

As aforementioned, chronic inflammation plays a vital role in the development of sarcopenia [1, 50]. A substantial body of studies has been conducted on the potential anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects of nutritional ingredients [36, 51]. It is recognized that potential benefits of caffeine for specific health outcomes are partially mediated by its anti-inflammatory properties [52]. C reactive protein, one typical hallmark of systematic inflammation, was used in the current study to conduct a mediation analysis. Our result shows that hs-CRP is not an important mediator, which was to some extent coherent with that from previous study [30].

This study had several strengths. Given that existing data on caffeine and sarcopenia are neither conducted in young people nor quantitative in caffeine content, we have newly added a recognition that caffeine intake is not associated with sarcopenia, but rather correlated to muscle mass in a nonlinear pattern among adults aged from 20 to 59. In addition, we utilized data from NHANES and also incorporated a comprehensive range of covariates, which made the results more representative and convincing.

Nevertheless, results in the present study should also be interpreted in the context of some limitations. Dietary recall of two single days may not be representative enough of one’s habitual caffeine intake. Secondly, interindividual differences in response to caffeine metabolism and excretion are largely influenced by genetic discrepancies, which are not available and explored here. In addition, the definition of sarcopenia herein is based on EWGPO2 criteria which is generally applied in elders, but not for young adults. Furthermore, inherent to observational study, no causal relationship or underlying mechanisms could be determined.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our finding has newly invoked that the association between dietary caffeine and muscle quantity in young adults cannot be simply described by a linear relationship, but rather present with a complex nonlinearity. Young and middle-aged adults should be cautious when considering a higher intake of caffeine for the purpose of building muscle. A daily caffeine consumption of 1.23 mg/kg is seemingly appropriate for 20–30 year adults, while approximately 0.64–1.49 mg/kg is recommended for middle-aged males. Further research into the effect of caffeine on muscle mass is warranted.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the efforts given by the NHANES team for collecting and providing data publicly to researchers. We also acknowledge all participants and staffs involved in this research.

Author contributions

LLZ and CZ contributed to the conception and design of this study. LLZ, JW and CZ were involved in the conduct of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the results. HJQ, LS and QLZ were responsible for the visualization. LLZ, JW and HJQ performed the literature review and drafting of the manuscript. LLZ, HJQ and CZ revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 82100545) and the Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (Grant Number: 2023RC234).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article or supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The NHANES study protocols had already been approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board, and all NHANES participants included in current study had signed a written informed consent form in person.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA, Sarcopenia. Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31138-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song E, Hwang SY, Park MJ, et al. Additive impact of diabetes and Sarcopenia on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a longitudinal nationwide population-based study. Metabolism. 2023;148:155678. 10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaudart C, Demonceau C, Reginster JY, et al. Sarcopenia and health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14(3):1228–43. 10.1002/jcsm.13243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell WK, Williams J, Atherton P, et al. Sarcopenia, Dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. Front Physiol. 2012;3:260. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung HN, Jung CH, Hwang YC. Sarcopenia in youth. Metabolism. 2023;144:155557. 10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan S, Larsson SC. Epidemiology of Sarcopenia: prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. Metabolism. 2023;144:155533. 10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolland Y, Dray C, Vellas B, et al. Current and investigational medications for the treatment of Sarcopenia. Metabolism. 2023;155597. 10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155597 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Rooks D, Swan T, Goswami B, et al. Bimagrumab vs Optimized Standard of Care for treatment of Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling older adults: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020836. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker C, Lord SR, Studenski SA, et al. Myostatin antibody (LY2495655) in older weak fallers: a proof-of-concept, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(12):948–57. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00298-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton JT, Barnette KG, Bohl CE, et al. The selective androgen receptor modulator GTx-024 (enobosarm) improves lean body mass and physical function in healthy elderly men and postmenopausal women: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2011;2(3):153–61. 10.1007/s13539-011-0034-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowery LM, Anderson DE, Scanlon KF, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: coffee and sports performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2023;20(1):2237952. 10.1080/15502783.2023.2237952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karayigit R, Naderi A, Akca F, et al. Effects of different doses of caffeinated coffee on muscular endurance, cognitive performance, and Cardiac Autonomic Modulation in Caffeine naive female athletes. Nutrients. 2020;13(1). 10.3390/nu13010002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Church DD, Hoffman JR, LaMonica MB, et al. The effect of an acute ingestion of Turkish coffee on reaction time and time trial performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2015;12:37. 10.1186/s12970-015-0098-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Zhou C, Guo T, et al. Current coffee consumption is associated with decreased striatal dopamine transporter availability in Parkinson’s disease patients and healthy controls. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):272. 10.1186/s12916-023-02994-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson SC, Orsini N. Coffee Consumption and Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients. 2018;10(10). 10.3390/nu10101501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Woolf B, Cronje HT, Zagkos L, et al. Appraising the causal relationship between plasma caffeine levels and neuropsychiatric disorders through mendelian randomization. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):296. 10.1186/s12916-023-03008-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dam RM, Hu FB, Willett WC. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):369–78. 10.1056/NEJMra1816604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, et al. Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ. 2017;359:j5024. 10.1136/bmj.j5024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonekura Y, Terauchi M, Hirose A, et al. Daily Coffee and Green Tea Consumption is inversely Associated with Body Mass Index, Body Fat percentage, and Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index in Middle-aged Japanese women: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). 10.3390/nu12051370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Huang YW, Wang LT, Zhang M, et al. Caffeine can alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by augmenting LDLR expression via targeting EGFR. Food Funct. 2023;14(7):3269–78. 10.1039/d2fo02701a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Buchanan R, et al. Coffee, including caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee, and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e013739. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhang M, et al. Consumption of coffee and tea with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):449. 10.1186/s12916-022-02636-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y, Je Y, Giovannucci E. Coffee consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a meta-analysis by potential modifiers. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(8):731–52. 10.1007/s10654-019-00524-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loftfield E, Cornelis MC, Caporaso N, et al. Association of Coffee drinking with mortality by genetic variation in Caffeine Metabolism: findings from the UK Biobank. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1086–97. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosso G, Micek A, Godos J, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in smokers and non-smokers: a dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(12):1191–205. 10.1007/s10654-016-0202-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawakami R, Tanisawa K, Ito T, et al. Coffee consumption and skeletal muscle mass: WASEDA’s Health Study. Br J Nutr. 2023;130(1):127–36. 10.1017/S0007114522003099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DY, Shin S. Sarcopenic obesity is associated with coffee intake in elderly koreans. Front Public Health. 2023;11:990029. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.990029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JH, Park YS. Light coffee consumption is protective against Sarcopenia, but frequent coffee consumption is associated with obesity in Korean adults. Nutr Res. 2017;41:97–102. 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwasaka C, Yamada Y, Nishida Y, et al. Association between habitual coffee consumption and skeletal muscle mass in middle-aged and older Japanese people. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(10):950–8. 10.1111/ggi.14264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valenzuela PL, Morales JS, Emanuele E, et al. Supplements with purported effects on muscle mass and strength. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58(8):2983–3008. 10.1007/s00394-018-1882-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilk M, Krzysztofik M, Filip A, et al. The effects of high doses of caffeine on maximal strength and muscular endurance in athletes habituated to Caffeine. Nutrients. 2019;11(8). 10.3390/nu11081912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Arnaud MJ. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of natural methylxanthines in animal and man. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011;200:33–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jager R, Purpura M, Wells SD, et al. Paraxanthine supplementation increases muscle Mass, Strength, and endurance in mice. Nutrients. 2022;14(4). 10.3390/nu14040893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Stavric B. Methylxanthines: toxicity to humans. 3. Theobromine, paraxanthine and the combined effects of methylxanthines. Food Chem Toxicol. 1988;26(8):725–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merk D, Greulich J, Vierkant A, et al. Caffeine inhibits oxidative stress- and low Dose Endotoxemia-Induced Senescence-Role of Thioredoxin-1. Antioxid (Basel). 2023;12(6). 10.3390/antiox12061244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Guo Y, Niu K, Okazaki T, et al. Coffee treatment prevents the progression of Sarcopenia in aged mice in vivo and in vitro. Exp Gerontol. 2014;50:1–8. 10.1016/j.exger.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oishi Y, Tsukamoto H, Yokokawa T, et al. Mixed lactate and caffeine compound increases satellite cell activity and anabolic signals for muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;118(6):742–9. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00054.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(7):439–55. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu Y, Hu CX, Liu X, et al. Moderate coffee or tea consumption decreased the risk of cognitive disorders: an updated dose-response meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2023. 10.1093/nutrit/nuad089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo H, Wang S, Peng H, et al. Dose-response relationships of tea and coffee consumption with gout: a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62(9):3043–50. 10.1093/rheumatology/kead019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong O, Marshall K, Sicova M, et al. CYP1A2 genotype modifies the effects of Caffeine compared with placebo on muscle strength in competitive male athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2021;31(5):420–6. 10.1123/ijsnem.2020-0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwasaka C, Nanri H, Hara M, et al. Interaction between Habitual Green tea and coffee consumption and ACTN3 Genotype in Association with skeletal muscle Mass and Strength in Middle-aged and older adults. J Frailty Aging. 2024;13(3):267–75. 10.14283/jfa.2024.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins BC, Laakkonen EK, Lowe DA. Aging of the musculoskeletal system: how the loss of estrogen impacts muscle strength. Bone. 2019;123:137–44. 10.1016/j.bone.2019.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JH, Park I, Shin HR, et al. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis controls muscle stem cell senescence through autophagosome clearance. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(1):177–91. 10.1002/jcsm.12653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berman NK, Honig S, Cronstein BN, Pillinger MH. The effects of caffeine on bone mineral density and fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(6):1235–41. 10.1007/s00198-021-05972-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miao Y, Zhao L, Lei S, et al. Caffeine regulates both osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation via the AKT, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1405173. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1405173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lippi L, de Sire A, Invernizzi M, Editorial. The role of bone-muscle crosstalk in secondary osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1454743. 10.3389/fendo.2024.1454743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosas-Carrasco O, Manrique-Espinoza B, López-Alvarenga JC, et al. Osteosarcopenia predicts greater risk of functional disability than Sarcopenia: a longitudinal analysis of FraDySMex cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2024;28(11):100368. 10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H, Qi G, Wang K, et al. Oxidative stress: roles in skeletal muscle atrophy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;214:115664. 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moua ED, Hu C, Day N, et al. Coffee consumption and C-Reactive protein levels: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). 10.3390/nu12051349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Ochoa-Rosales C, van der Schaft N, Braun KVE, et al. C-reactive protein partially mediates the inverse association between coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: the UK Biobank and the Rotterdam study cohorts. Clin Nutr. 2023;42(5):661–9. 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article or supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.