Abstract

Background

Dendrobium catenatum is a perennial herb of the genus Dendrobium orchidaceae. It has been known as “Golden Grass, Soft Gold” since ancient times with effects of strengthening the body, benefiting the stomach, generating body fluid, nourishing Yin and clearing internal heat. The flowers of D. catenatum have anti-oxidation, immune regulation and other biological activities. The composition analysis of flowers showed that flavonoid glycosides were significantly accumulated in floral tissue. However, in the flowers of D. catenatum, there was only one case of the UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) responsible for the glycosylation of flavonoids has been reported.

Result

In this study, a new UGT (named UGT708S6) was cloned from D. catenatum flowers rich in O-glycosides and C-glycosides, and its function and biochemical properties were characterized. Through homology comparison and molecular docking, we identified the key amino acid residues affecting the catalytic function of UGT708S6. The glycosyltransferase UGT708S6 was characterized and demonstrated C-glycosyltransferase (CGT) activity in vitro assay using phloretin and 2-hydroxynaringenin as sugar acceptors. The catalytic promiscuity assay revealed that UGT708S6 has a clear sugar donor preference, and displayed O-glycosyltransferase (OGT) activity towards luteolin, naringenin and liquiritigenin. Furthermore, the catalytic characteristics of UGT708S6 were explored, shedding light on the structural basis of substrate promiscuity and the catalytic mechanism involved in the formation of flavonoid C-glycosides. R271 was a key amino acid residue site that sustained the catalytic reaction. The smaller binding pocket resulted in the production of new O-glycosides and the reduction of C-glycosides. This highlighted the importance of the binding pocket in determining whether C-glycosides or O-glycosides were produced.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that UGT708S6 holds promise as a new glycosyltransferase for synthesizing flavonoid glycosides and offer valuable insights for further understanding the catalytic mechanisms of flavonoid glycosyltransferases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12896-024-00923-9.

Keywords: Flavonoid C-glycoside, C-glycosyltransferase, Dendrobium catenatum flower, Catalytic characteristics, Catalytic mechanism

Background

Flavonoids, as a class of secondary metabolites in plants, have a wide range of medicinal value and exhibit structural diversity due to various forms of modifications such as hydroxylation, methylation, acylation, and glycosylation [1]. Recent research has highlighted the pharmacological potential of flavonoid glycosides, demonstrating strong antioxidant properties, an inhibitory effect on the growth of melanoma and colon cancer cell growth [2, 3], and potential in curbing cancer progression regulating atherosclerosis [4, 5], cardiac function, and vascular biology in animal models [6, 7]. Additionally, flavonoid glycosides contribute to the prevention of chronic inflammation in humans [8]. Samoa Ethnomedicines have been found to contain flavonoid glycosides as their primary anti-inflammatory active components [9].

Glucose is the most common sugar moiety in naturally occurring flavonoid C-glycosides, arabinose, rhamnose and other sugars can also be present [10]. Through similarity and principal component analysis of the chromatographic fingerprinting profiles, it was found that the contents of flavonoid O-glycosides and C-glycosides were predominant in Dendrobium catenatum flowers, which included 11 C-glycosides and 6 O-glycosides, these glycosides were found to be glycosylated with glucose, arabinose, rutinose, rhamnose, xylose, and other sugar moieties [11].

D. catenatum is a perennial epiphytic herb belonging to the genus Dendrobium in the Orchidaceae family [12, 13]. It is known for its beneficial properties such as soothing the liver and the gallbladder, delaying aging and strengthening the spleen and stomach [14]. The flowers of D. catenatum serve as a distinctive natural resource with a rich history of medicinal and culinary use in China. Studies have shown that the flowers possess antioxidant properties that can help lower blood pressure and enhance immune function. It is essential to further explore the medicinal potential of the flowers and to increase the overall economic value of D. catenatum [11].

Glycosylation is the most common modification of flavonoids in plants and flavonoids typically exist in O-glycosides or C-glycosides [15]. In O-glycosides, the sugar moiety is bound to the hydroxyl group of the aglycone, while in C-glycosides the sugar moiety is directly linked to a carbon atom in the aglycone skeleton [16, 17]. OGT (O-glycosyltransferase) catalyzes a reaction akin to an SN2 single displacement mechanism, often facilitated by specific histidine and aspartate residues. These residues form a His-Asp pair that deprotonates the substrate’s hydroxyl group, enabling it to attack the anomeric carbon of UDP-sugar, resulting in the formation of an O-glycosidic bond [18, 19]. This catalytic mechanism for O-glycosylation does not directly translate to C-glycosylation. CGT (C-glycosyltransferase) also mediates a single displacement reaction similar to SN2 [20]. However, in this case, it is suggested that the His-Asp pair deprotonates the substrate’s phenolic hydroxyl group, allowing the aromatic carbon, which has gained nucleophilicity through resonance, to launch a nucleophilic attack on the anomeric carbon of UDP-sugar, leading to the formation of a C-glycosidic bond [21, 22]. Generally, functional differences were dependent on structural differences.

Proteins with similar amino acid sequences may have similar biological functions [23]. What is interesting, there are also some reports that some proteins belong to the same family with high sequence identity but perform totally different biological functions [24]. Such as Mi CGTb and Mi CGT from Mangifera indica, which have a sequence identity of 90%, one of them has capacity di-C-glycosylation and showed high catalytic activity regioselectivity, the other does not have this ability [25]. There is another report of Ii UGT71B5a and Ii UGT71B5b from Isatis indigotica Fort., one of them was capable of efficiently producing both pinoresinol monoglycoside and diglycoside, but the other only produced monoglycoside, and exhibited considerably low activity [26].

In light of the research potential of flavonoid glycosides found in D. catenatum flowers, it is essential to uncover the biosynthetic pathway of these compounds for future genetic and metabolic engineering endeavors in plants. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate glycosyltransferases in D. catenatum flowers that possess the synthesis of flavonoid glycosides. There is only one report on the glycosyltransferase of D. catenatum, which demonstrating its ability to catalyze the production of di-C-glycosides and O- glycosides [10], This report also focuses on genomic and phylogenomic analysis, however, the underlying mechanisms have not been studied. If an enzyme’s sequence is highly similar to Dca CGT, will it exhibit catalytic differences, such as those combinations mentioned above? This finding could offer valuable insight and serve as a reference for further investigation.

In this work, glycosyltransferases in flowers were investigated for their ability to catalyze the synthesis of flavonoid glycosides. Through homology comparison and evolutionary tree analysis, UGT708S6 was identified. The tissue/organ-specific expression patterns and stress responses of UGT708S6 were analyzed using transcriptome data. The catalytic products of UGT708S6 were identified by UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. Structural biology and molecular docking were employed to analyze key amino acid sites that influence the catalytic properties and efficiency. Structure‒function relationships were explained by comparing the products catalyzed by the mutants and the wild-type protein. These findings underscore the significant role of glycosyltransferases in plant glycosylation and the regulation of physiological functions.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents, cell culture, plant material

In this study, all standards and chemical reagents were purchased from ChemFaces (Shanghai, China). All antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA, USA).

Dendrobium catenatum was harvested from a standard greenhouse in the Lin’an District (30°20'30"N, 119°26'11"E, 280 m above sea level), Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China. The flowers were collected in May 2021 from original D. catenatum plants potted in a substrate of pine bark.

Phylogenetic tree construction and bioinformatics analysis

Combining the reported genomic and transcriptomic data of D. catenatum, we screened the candidate UGTs by performing an integrated genomic and transcriptomic data analysis of D. catenatum. The plant secondary product glycosyltransferase (PSPG) box is a highly conserved motif among plant UGTs, according to this, members of the UGT gene family in D. catenatum were identified using Hidden Markov Model (HMM), the candidate UGTs were confirmed in the NCBI database through BLASTp algorithm. Then completed amino acid sequences of UGTs known were collected from NCBI for analysis (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/), and constructed a phylogenetic tree by MEGA7 (https://www.megasoftware.net/) to screen the UGT sequences of D. catenatum. Accession numbers of known UGTs in the phylogenetic tree are shown in Supplementary Table S3. The hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of the amino acid sequence were analyzed using the Prot-Scala tool in ExPASy (https://web.expasy.org/protscale/). The physicochemical properties were predicted using the pI/Mw tool in ExPASy Compute (http://web.expasy.org/compute/Pi/) and are summarized in Table 1. The UGT sequence was analyzed with the TMHMM server (version 2.0, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) to predict potential transmembrane domains. SignalP-5.0 Server was used for signal peptide prediction (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-5.0/).

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of UGT708S6

| Bioinformatics | UGT708S6 |

|---|---|

| Number of amino acids | 453 |

| Molecular weight | 48609.33 |

| Theoretical isoelectric point (pI) | 5.32 |

| Instability index | 50.90 |

| Aliphatic index | 103.16 |

| Grand average of hydropathicity | 0.242 |

Molecular cloning of UGT708S6

The RNA extraction method was performed according to the instructions of the TaKaRa MiniBEST Plant RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Full-length cDNAs of UGT708S6 were amplified by PCR using gene-specific primer pairs (TableS2).

Subcellular localization of UGT708S6

The empty vector pEAQ-GFP (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) was digested with FastDigest enzymes Xho I and Age I (Thermo, USA). The UGT708S6 gene was inserted into the pEAQ-GFP vector, where it was fused with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and controlled by the 35 S cauliflower mosaic virus promoter. These constructs were then introduced into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 for infiltration and transient expression in N. benthamiana epidermal cells. The results were documented after 2 days of transformation with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. The GFP fluorescence was visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 laser confocal scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

The pattern of gene expression in vivo

The transcriptome data (the RNA-seq datasets) were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The tissue and organ expression profiling of UGT708S6: leaf (SRR4431601), root (SRX2938667), green root tip (SRR4431599), white part of root (SRR4431598), stem (SRR4431600), flower bud (SRR4431603), sepal (SRR4431597), labellum (SRR4431602), pollinia (SRR5722145) and gynostemium (SRR4431596). D. catenatum plantlets were treated with jasmonic acid (JA) and Sclerotium delphinii (P1): PRJNA732289 [27]. Drought stress: SAMN09269105-SAMN09269111 [28]. Cold stress: PRJNA314400. Then, the transcriptional information of UGT708S6 was statistically analyzed.

Protein expression, purification and Western blotting of UGT708S6

For the expression of UGT708S6, the pGEX-4T-1 vector containing UGT708S6 was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) through heat shock transformation. The expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, followed by continued growth at 16°C and 110 rpm for 16–18 h. Protein expression was detected using an anti-GST antibody (1:1,000) and a horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000), followed by enhanced chemiluminescence. Densitometric analysis of films was performed using ImageJ software. Supernatants were processed using an AKTA Purifier system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA), and protein concentrations were determined with a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer 300 (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). The purified proteins were then stored at 4°C for catalytic assays.

UGT708S6 activity and HPLC/electrospray-ionization exactive mass spectrometry (ESI-EX MS) analysis

Following protein purification, the catalytic performance of UGT708S6 was assessed through an enzymatic reaction conducted in a 30°C water bath for 1 h. The reaction mixture consisted of 20 µg of purified protein, phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1 mM each of uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-Glc), uridine diphosphate rhamnose (UDP-Rha), and uridine diphosphate xylose (UDP-Xyl), in addition to 8 µg of various flavonoid compounds. The total volume of the reaction system was 100 µL. The reaction was terminated by adding 100 µL of ethyl acetate, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 min to collect the upper layer (ethyl acetate layer) for subsequent HPLC analysis. The analysis platform was LC-Q/TOF-MS (Agilent, 1290 Infinity LC, 6530 UHD and Accurate-Mass Q-TOF/MS, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) Electrospray ionization (ESI) was used for negative ion mode mass spectrometry detection, and the mass spectrometry conditions as follows: capillary voltage, 2.5 KV; cone voltage, 30 kV; ion source temperature, 150°C; cone gas flow, 50 L h− 1; desolvation gas temperature, 450°C; desolvation gas flow, 600 L h− 1. The HPLC was equipped with a Agilent Poroshell 120 SB-C18 column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL⋅min− 1, and the column temperature was maintained at 30°C. The mobile phase consisted of A (0.1% formic acid aqueous solution) and B (acetonitrile). The chromatographic gradient was: 0–12 min: linear gradient from 5 to 95% mobile phase B.

Influence of reaction time, pH, temperature and metal ions

To investigate the optimal pH reaction conditions, the reaction system was adjusted using different buffer solutions with pH values ranging from 4.0 to 6.0 (citrate buffer), 7.0 to 8.0 (phosphate buffer) and 9.0 to 10.0 (glycine-NaOH buffer). The optimal reaction temperature was determined by incubating the reactions at various temperatures between 20 and 45°C. To assess the necessity of divalent metal ions for UGT708S6, CaCl2, BaCl2, NaCl, MgCl2, KCl, MnCl2, and ZnCl2 were used at a final concentration of 5 mM. Time-course experiments involved setting different reaction times ranging from 0 to 12 h. All reactions were repeated three times. All assays were performed with UDP-Glc as a donor and phloretin as an acceptor, and 100 µL ethyl acetate was added to terminate the reaction. Following centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 min, the upper layer (ethyl acetate layer) was collected for analysis.

Enzyme kinetic parameters of UGT708S6

The kinetic parameters Km and kcat were determined for the reaction efficiency of UGT708S6. In this study, UDP-Glc was used as the sugar donor, and phloretin and 2-hydroxynaringenin were used as sugar acceptors to determine the kinetic parameters. Dihydroquercetin was used as the internal standard. Phloretin/2-hydroxynaringenin and dihydroquercetin were mixed at a ratio of 9:1 (5 mg/mL each), these two solutions were mixed to the final concentration of 5 mg/mL (Phloretin: dihydroquercetin = 4.5 mg/mL: 0.5 mg/mL; 2-hydroxynaringenin: dihydroquercetin = 4.5 mg/mL: 0.5 mg/mL), then diluted with methanol to the concentration of 1, 0.9, 0.8, 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, 0.4 mg/mL. Purified protein was added into the experimental group, the negative control consisted of empty vector pGEX-4T-1. All reactions were analyzed by liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. LC-MS conditions are the same as Materials and methods 2.7. (TableS1). The resulting data was fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation to calculate the Michaelis constants (V0 = Vmax·[S]/(Km+[S])). The kinetic parameters were determined through the linear equation derived from the double-reciprocal plot (1/V0 = Km/Vmax·1/[S] + 1/Vmax).

Homology model construction, and site-directed mutagenesis

The proteins were analyzed using UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/), and the stereo conformation of UGT708S6 was obtained. Chem3D 20.0 (Cambridge Software Company, USA) was utilized to construct the three-dimensional conformation structures of phloretin and 2-hydroxynaringenin. The structures were parameterized using AutoDockTools [29]. ProteinsPlus online server (https://proteins.plus) was used to predict protein-ligand binding pockets and assess their properties [30]. Grid boxes were established based on literature findings and protein homology comparisons to determine the molecular docking range. The grid box coordinates for UGT708S6 were set as follows: X-center: -8.597. Molecular docking calculations were carried out utilizing AutoDockTools 1.5.7, and the structure of the protein-substrate complex was visualized, analyzed, and postprocessed with PyMOL 1.7.6. According to the results of molecular docking, point mutations were created using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, Palo Alto, USA). The primers utilized in this step are detailed in Table S2. The resulting product of site-directed mutagenesis was then introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3), the mutant proteins were purified using the same protocol for recombinant wild-type (UGT708S6) for the purpose of analyzing the ability to catalyze phloretin and 2-hydroxynaringenin.

Data analysis and graph preparation

All assays were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., San Diego, CA), and the data were presented as the mean ± SEM. Data that followed a normal distribution were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

Phylogenetic tree construction and bioinformatics analysis of UGT708S6

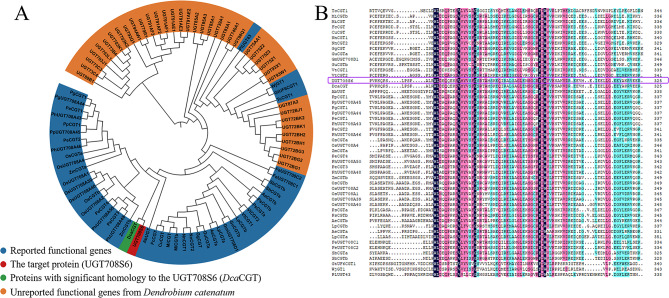

A phylogenetic tree of D. catenatum UGTs was constructed by comparing their full-length amino acid sequences with plant UGTs of known functional properties (Fig. 1A). Homology analysis shows that UGT708S6 is very similar to the identified plant CGT (Dca CGT). Amino acid sequence comparison results show that the two proteins are 99% similar (Fig. S6). Dca CGT is the only CGT that has been verified to responsible for the glycosylation of flavonoids in D. catenatum. It could specifically catalyze not only di-C-glycosylation but also O-glycosylation. UGT708S6 (GenBank accession No. LOC110103872) was identified as a potential CGT of D. catenatum, encoding a protein of 453 amino acids. The predicted molecular weight is 48.609, and the theoretical isoelectric point is 5.93 (Table 1). The hydrophobicity profile indicated that UGT708S6 is an unstable protein (instability index > 40) with an average hydrophobicity of 0.242 (Fig.S1A, Table 1). The N-terminal transmembrane domain might interfere with solubility (Fig. S1B). The signal peptide prediction results showed that there is no signal peptide because the probability is 0.007% as predicted by SignalP-5.0 Server. (Fig. S1C). Structural analysis revealed that UGT708S6 predominantly consisted of α-helix (45.03%), followed by irregular coiling (35.10%), extended strand (13.02%) and β-folding (6.84%) (Fig. S1D). These are consistent with the basic characteristics of the GT protein family, which contained the UGT conserved PSPG box (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

UGT708S6 is speculated to be involved in the biosynthesis of flavonoid glycosides. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of D. catenatum UGT family. (B) Conserved sequence obtained by multiple sequence alignment of UGT sequences

Subcellular localization and the pattern of gene expression in vivo

The UGT708S6 was successfully amplified from the cDNA of D. catenatum using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Subsequently, the coding sequence (CDS) region was inserted into a pEAQ-GFP vector (N-terminal fusion of GFP), and transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 for subcellular localization studies. The results revealed that in control group (empty vector) the GFP fluorescence dispersed throughout the entire cell, whereas the GFP-UGT708S6 fusion protein exhibited specific localization in the cytoplasm of tobacco mesophyll cells (Fig. 2A). These results clearly demonstrate that UGT708S6 is a cytoplasm-localized protein, similar to most UGTs of plants [31, 32]. Transcriptome data analysis revealed that UGT708S6 exhibited highest expression in flowers and pollinia, which are consistent with the preferential accumulation of flavonoid glycosides in these tissues [10, 11]. (Fig. 2B). To investigate the expression patterns of UGT708S6 under stress conditions, we conducted an expression analysis under Jasmonic acid (JA), Sclerotium delphinii (P1), drought, and cold stress. Under drought stress, UGT708S6 showed low expression levels and swiftly recovered upon rehydration, with a rhythmic expression pattern peaking during the night (Fig. 2C). JA is considered as a stress hormone implicated in plant response to stress [33]. Treatment with JA resulted in a significant increase in UGT708S6 expression, indicating that UGT708S6 can respond to the induction and may participate in the JA-mediated defense response (Fig. 2D). Sclerotium delphinii, a necrotrophic pathogen, is responsible for the southern blight disease, which causes widespread loss in the cultivation of D.catenatum [34]. P1 infection led to a slight reduction in the expression of UGT708S6, indicating that UGT708S6 may not be involved in the resistance to the southern blight disease (Fig. 2E). When P1 and JA were co-administered, UGT708S6 expression was significantly up-regulated (Fig. 2F). The expression level of UGT708S6 significantly increased under cold stress, suggesting its potential involvement in co-regulating plant physiology and metabolism to enhance cold tolerance (Fig. 2G). Overall, it is hypothesized that UGT708S6 may play a role in responding to abiotic stresses.

Fig. 2.

The expression pattern of UGT708S6 in vivo. (A) Subcellular localization of UGT708S in N. benthamiana epidermal cells. The pEAQ-GFP was used as control. Green fluorescence, bright field and merged images were taken under confocal. (B) Relative expression levels in different organs. Leaf: leaf, Root: root, RoGT: green root tip (SRR4431599), Rootw: white part of root, Stem: stem, Flow: flower bud, Sepa: sepal, Labe: labellum, Poll: pollinia and Gyno: gynostemium. (C) Effects of drought and re-watering treatment on relative expression levels, the re-watering time is 15:30 on the 1st and 8th day. Control: normal watering, DR2-2: 2nd day after drought treatment at 06:30, DR7-1/2: 7th day after drought treatment at 06:30 and 18:30, DR8-2: 8th day after drought treatment at 18:30, DR10-1/2: 10th day after drought treatment at 06:30 and 18:30. (D) Effects of JA treatment on the relative expression level. (E) Effects of P1 infection on the relative expression level. (F) Effect of combined administration of P1 and JA on the relative expression level. (G) Effect of cold treatment on the relative expression level

Substrate promiscuity of UGT708S6

The CDS of UGT708S6 was inserted into the vector of pGEX-4T-1 with a N-terminal GST tag and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The predicted molecular weight of the fusion proteins is 94.62 kDa. Western blot analysis revealed the presence of the fusion proteins as a band ranging from 70 to 100 kDa (Fig. S2).

Previous studies have reported that the identified glycosyl acceptors for flavonoid glycosides in flowers are kaempferol, isorhamnetin and apigenin [11]. Additionally, to explore the substrate spectrum of UGT708S6, a variety of flavonoids were chosen as potential glycosyl acceptors. We used a panel of 14 flavonoid compounds as potential sugar acceptors, and used uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-Glc), uridine diphosphate rhamnose (UDP-Rha) and uridine diphosphate xylose (UDP-Xyl) as sugar donors to investigate the substrate promiscuity of UGT708S6 (Fig. 3A). The crude protein was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. The purified protein was used to investigate the catalytic activity. The empty pGEX-4T-1 vector was used in the same procedure to produce control GST protein as the control group. LC-Q/TOF-MS analyss of reaction products revealed substrate promiscuity of UGT708S6 for both the acceptors and donors. UGT708S6 was found to catalyze the glycosylation of phloretin (1), luteolin (4), naringenin (9), liquiritigenin (12) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) with three different sugar donors (Fig. 3B). UGT708S shows good catalytic activity for phloretin (1) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14).

Fig. 4.

LC/MS analysis of enzymatic reaction products of UGT708S6 in vitro. (A) Phloretin (1) and the enzymatic product 1a, 1b. (B) 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) and the enzymatic product 14a, 14b, 14c. (C) Luteolin (4) and the enzymatic product 4a. (D) Naringenin (9) and the enzymatic product 9a, 9b. (E) Liquiritigenin (12) and the enzymatic product 12a, 12b. The sugar donors, sugar acceptors, experimental procedures and conditions of the control group were the same as those of the test group, except that UGT708S6 was not used. For flavonoid C-glycosides, when the sugar moiety is glucose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C4H8O4 (120) and C3H6O3 (90). When the sugar moiety is xylose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C3H6O3 (90) and C2H4O2 (60). When the sugar moiety is rhamnose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C4H8O3 (104) and C3H6O3 (74). For flavonoid O-glycosides, when the sugar moiety is glucose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C6H10O5 (162). When the sugar moiety is xylose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C5H8O4 (132). The sugar donors and sugar acceptors that cannot be catalyzed to form glycosides using UGT708S6 are shown in Fig. S3

Fig. 3.

Catalytic promiscuity of UGT708S6 in vitro. (A) The structure of flavonoid acceptors. 1: phloretin, 2: daidzein, 3: kaempferol, 4: luteolin, 5: apigenin, 6: quercetin, 7: diosmin, 8: dihydroquercetin, 9: naringenin, 10: isorhamnetin, 11: eriodictyol, 12: liquiritigenin, 13: myricetin, 14: 2-hydroxynaringenin. (B) Relative activity of each flavonoid accoptor catalyzed by UGT708S6 when using UDP-Glc, UDP-Xyl and UDP-Rha as sugar donors. N.D.: products not detected. The total product yield of phloretin with UDP-Glc was defined as 100% relative activity

In the present LC-Q/TOF-MS analysis, new products showed the characteristic fragmentation patterns of C-glycosides and O-glycosides. In the reaction mixtures of phloretin (1)-UDP-Glc and phloretin (1)-UDP-Xyl, new products 1a and 1b were observed (Fig. 4A). The MS/MS spectrum showed the fragment ions of 1a were at m/z 345 [M-H-90]− and m/z 315 [M-H-120]−, and the fragment ions of 1b were at m/z 345 [M-H-60]− and m/z 315 [M-H-90]−. [M-H-60]−, [M-H-90]− and [M-H-120]− are characteristic ions of C-glycosidic flavonoids, indicating that 1a and 1b were C-glycoside of phloretin (1) [35–37]. Likewise, the 14a and 14b were identified as C-glycosides (Fig. 4B). In addition, [M-H-104]− and [M-H-74]− are characteristic ions of C-rhamnosides [36], indicating 14c was a C-rhamnoside (Fig. 4B). The new products 4a (Fig. 4C), 9a (Fig. 4D) and 12a (Fig. 4E) were identified as O-glucosides according to the diagnostic [M-H-162]− fragment ions in the MS/MS spectra. The new product 9b (Fig. 4D) and 12b (Fig. 4E) were identified as O-xylosides according to the diagnostic [M-H-132]− fragment ions in the MS/MS spectra. The above phenomenon implied that UGT708S6 was an interesting enzyme, that could not only be responsible for phloretin (1) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) C-glycosylation, but also had a wide range of sugar donors and sugar acceptors.

Fig. 5.

Biochemical properties of UGT708S6 in vitro. (A) Reaction temperature. (B) Reaction buffer pH values. (C) Reaction time. The ordinate is the relative activity level

Biochemical properties and kinetic parameters of UGT708S6

Biochemical properties of UGT708S6 were investigated using phloretin (1) as the acceptor and UDP-Glc as the sugar donor. Catalysis activity of UGT708S6 was tested in a temperature range of 20–60°C, the optimal activity was detected at 35°C (Fig. 5A). Analysis of the enzyme activity between pH 4.0 and 10.0 showed that the optimal pH value was observed at pH 7.0. When the reaction pH was close to its pI (pI = 5.32), UGT708S6 had the lowest solubility and lowest catalytic activity (Fig. 5B). The yield of the glycosylation product 1a increased within 4 h, when the reaction time was between 0.5 and 2 h, the reaction between enzyme and substrate showed a relatively good linear relationship with time, and the growth rate was leveling off after 4 h (Fig. 5C). To test the effects of metal cations on activity of UGT708S6, different cations including K+ (control), Ba2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Na+ and Zn2+ were individually used. The result showed that metal cations had no effect on activity, probably because there was no interaction between the ions and the catalytic residues (Fig. S5). The kinetic parameters of UGT708S6 were determined when UDP-Glc was used as a donor and phloretin (1) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) were used as acceptors (Table 2). The kcat/Km value showed that the catalytic efficiency for 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) was higher than that for phloretin (1) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Enzymatic kinetic parameters of recombinant protein UGT708S6

| UGT | Sugar acceptor | Vmax (µM/s) | Km (µM) | kcat (s− 1) | kcat/Km (µM− 1·s− 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGT708S6 | Phloretin | 0.158 | 545.831 | 0.563 | 1.03 × 10− 3 |

| 2-Hydroxynaringenin | 0.128 | 276.900 | 0.907 | 3.283 × 10− 3 |

Site-specific mutants of UGT708S6

Extensive enzyme reactions revealed that UGT708S6 could catalyze the C-glycosylation of phloretin (1) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) into their corresponding C-glycosides. To identify key residues influencing catalytic activities of UGT708S6, we conducted homology modeling, molecular docking, and site-directed mutagenesis studies. Homology modeling was performed with SWISS-MODEL using the crystal structure of Mi CGT (PDB ID: 7VA8) as a template. Among the glycosyltransferases with determined protein structures, Mi CGT displays the highest sequence similarity to the target protein UGT708S6, exhibiting a 44.8% sequence homology. Additionally, Mi CGT is also capable of catalyzing the glycosylation of flavonoid compounds [38]. The homology model showed that UGT708S6 has a typical GT-B fold that consists of two β/α/β Rossmann-like domains [39]. Their N- and C-terminal domains form a cleft that forms the substrate-binding site, and the acceptor mainly binds to the N-terminal domain (Fig. 6A).

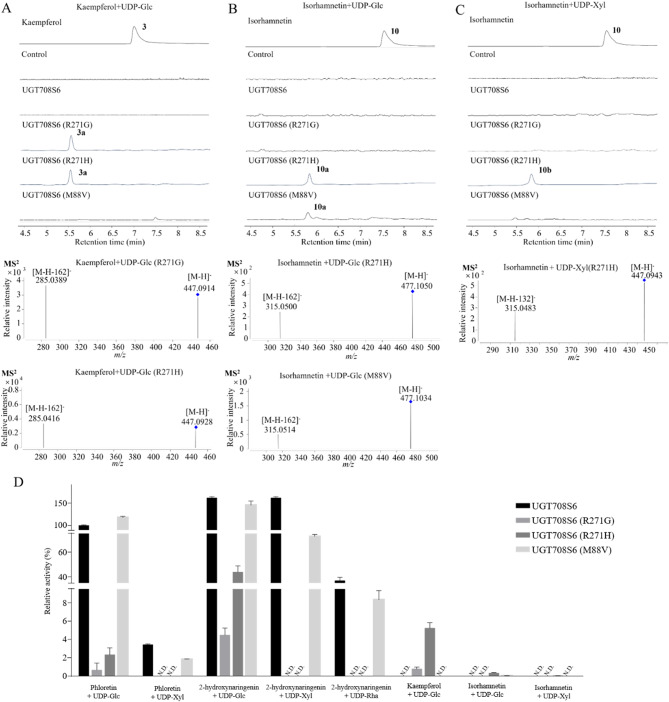

Fig. 7.

LC/MS analysis enzymatic products of UGT708S6 mutants in vivo. (A) Kaempferol (3) and the enzymatic product 3a. (B) Isorhamnetin (10) and the enzymatic product 10a. (C) Isorhamnetin (10) and the enzymatic product 10b. (D) Relative activity of C-/O- glycosylated compounds catalyzed by UGT708S6 mutants (Please see the Supplementary Fig. S9-S10 for each comparison results): The sugar donors, sugar acceptors, experimental procedures and conditions of the control group were the same as those of the test group, except that UGT708S6 mutants was not used. For flavonoid O-glycosides, when the sugar moiety is glucose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C6H10O5 (162). When the sugar moiety is xylose, the neutral loss from the mother ion ([M-H]−) are C5H8O4 (132). The sugar donors and sugar acceptors that cannot be catalyzed to form glycosides using UGT708S6 mutants are shown in Fig. S3

To further clarify the binding pocket and key amino acid residues of UGT708S6, molecular docking was performed. The UDP-Glc was prepared as the sugar donor. Phloretin (1) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) were prepared as the sugar acceptors respectively. The binding sites of the donor and acceptor were calculated and docking separately as shown in Fig. 6. The binding pocket contained the highly conserved catalytic dyad His21-Asp115 [40]. The acidic amino acid Asp115 helps the general base His21 deprotonate the hydroxyl group at 2’-/6’-position of phloretin (1) and 2’-/6’-position of 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) through conjugation effects, allowing the ortho-aromatic carbon to undergo nucleophilic attack to the anomeric carbon of the sugar donor and produce the C-glycosides (the black arrows in Fig. 6). In addition, the hydroxyl group at the 6’-position of phloretin (1) and 6’-position of 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) formed hydrogen bonds interaction with the 5-position nitrogen atom of Arg271 residues. The hydrogen bond played an important role in anchoring the sugar acceptor in the binding pocket. It brought the nucleophilic aromatic carbon in close proximity to the UDP-Glc hetero carbon at the appropriate position to initiate the catalytic reaction. Although Met88 did not directly interact with sugar acceptors, this residue contributed to the formation of the substrate-binding pocket. To verify the function of these predicted key residues and improve catalytic efficiency of UGT708S6, we mutated Met88 into valine and Arg271 to histidine or glycine [38, 41]. Protein structures were analyzed using the Proteins Plus online server to predict protein-ligand binding pockets and assess their properties. The results showed that the binding pocket volume of UGT708S6 (3336.45 Å3) was larger compared to the mutants (M88V: 2860.03 Å3, R271G: 2825.28 Å3, R271H: 2861.89 Å3). This indicated that both Met88 and Arg271 were important residues that constitute the binding pocket (Fig. 6). The AutoDock program was utilized to predict the binding energy of each docked structure (UGT708S6: -5.93 kcal·mol− 1, M88V: -7.46 kcal·mol− 1, R271G: -6.25 kcal·mol− 1, R271H: -5.63 kcal·mol− 1). These results suggest that the mutant M88V may catalyze phloretin (1) with reduced protein–ligand binding energy, potentially leading to increased activity. For 2-hydroxynaringenin (14), there was small difference in binding energy between the wild type and the mutants (UGT708S6: -6.06 kcal·mol− 1, M88V: -6.58 kcal·mol− 1, R271G: -6.58 kcal·mol− 1 and R271H: -6.31 kcal·mol− 1). These mutations might not yield an increase in catalytic activity (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Homology modeling, molecular docking and site-directed mutagenesis of UGT708S6. (A) Overall 3D modeling structure of UGT708S6. (B) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-phloretin. (C) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-M88V-phloretin. (D) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-R271G-phloretin. (E) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-R271H-phloretin. (F) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-2-hydroxynaringenin. (G) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-M88V-2-hydroxynaringenin. (H) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-R271G-2-hydroxynaringenin. (I) Catalytic structural domain of UGT708S6-R271H-2-hydroxynaringenin. The protein molecules are shown as cartoons. The key residues and substrate molecules are shown as sticks. Green: N-terminal structural domain, cyan blue: C-terminal structural domain. The yellow dashed lines are hydrogen bonding interactions. The black arrows indicate direction of electron transfer

We used a panel of 14 sugar acceptors and 3 sugar donors (Fig. 3) to investigate the catalytic activity of the mutants. The results showed that mutants can catalyze the formation of new glycosides (Fig. 7). The new products 3a (Fig. 7A) and 10a (Fig. 7B) were identified as O-glucosides of kaempferol (3) and isorhamnetin (10) respectively according to the diagnostic [M-H-162]− fragment ions in the MS/MS spectra. The new product 10b (Fig. 7C) were identified as the O-xyloside according to the diagnostic [M-H-132]− fragment ions in the MS/MS spectra.

When using phloretin (1) and 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) as sugar acceptors, the catalytic products of the mutant and wild type are comparable (1a, 1b, 14a, 14b and 14c). The catalytic activity of the mutants R271G and R271H using UDP-Glc as donor were significantly reduced compared with the wild-type, and were lost completely towards the sugar donors UDP-Xyl and UDP-Rha. This indicated the importance of R271 as a key residue for catalytic reaction. When using phloretin (1) and UDP-Glc as the sugar acceptor and the sugar donor, the mutant M88V showed the improvement of catalytic activity of 18.0% compared with wild-type. When using phloretin (1) and UDP-Xyl as the sugar acceptor and the sugar donor, the mutant M88V displayed similar activity to the wild-type. When using UDP-Xyl and UDP-Rha as sugar donors, the mutant M88V displayed lower activity to the wild-type.

Discussion

In plants, glycosylation is one of the most widespread modification patterns of secondary metabolites [39]. Several O- glycosyltransferases have been identified and characterized in plant species like Isatis indigotica [26], Arabidopsis thaliana [19], Clitoria ternatea [42] and Zea mays [43]. However, the number of identified O-glycosyltransferases in plants is greater than that of C-glycosyltransferases reported to date, resulting in fewer mechanistic studies focused on C-glycosyltransferases. Over the past few decades, Tc CGT1 was the first flavonoid CGT to have its crystal structure elucidated [41]. Through a combination of molecular docking and site-directed mutagenesis, the catalytic mechanism of Tc CGT1 has been clarified, thereby initiating the exploration of plant CGTs. Additionally, the molecular mechanism of Mi CGT was revealed through an alanine scan, iterative saturation mutagenesis, and crystallography [41]. The study of CGTs and their catalytic mechanisms has consistently been a prominent topic of interest. Studies on Ab CGT and Tc CGT1 have provided insights into carbon and oxygen glycosylation conversion, potentially facilitating the development of protein engineering to improve UGTs [41, 44].

In this study, the UGT708S6 gene was successfully cloned from D. catenatum cDNA. The expression patterns of this gene, as well as the catalytic function and characteristics of the protein, were investigated and confirmed for the first time. In the flowers of D. catenatum, only one case of the UGT (Dca CGT) responsible for the glycosylation of flavonoids has been reported. The study of Dca CGT primarily concentrates on genomic and phylogenomic analysis, and enzyme activity toward three different substrates, but the underlying catalytic mechanism is fascinating but not fully understood [10]. In comparison to Dca CGT, we tested UGT708S6’s ability to catalyze multiple flavonoid substrates, including but not limited to 2-hydroxynaringenin, phloretin, and apigenin. Additionally, the glycosylation reaction was optimized with other types of sugar donors, which not limited to UDP-Glc. Comprehensive validation of the catalytic versatility of UGT708S6 revealed a distinct sugar donor preference and demonstrated OGT activity towards luteolin, naringenin, and liquiritigenin. However, it was unable to catalyze di-C- glycosylation. A comparison of the amino acid sequences of Mi CGT, Dca CGT, and UGT708S6 revealed that the side chains of amino acids at positions 415 and 417 in Dca CGT are larger than those in UGT708S6. Consequently, we speculate that the substrate binding domain near Val415 and Gly417 of Dca CGT (Fig. S6-S8) is sufficiently spacious to accommodate monoglycoside products as substrates for the second step of the di-glycosylation reaction. Notably, the kinetic parameters of Dca CGT were not evaluated, leading us to select Ab CGT as a representative template [44]. When phloretin was used as the substrate, the kcat/Km value of UGT708S6 was approximately 7.5% that of Ab CGT. When 2-hydroxynaringenin was used as the substrate, the kcat/Km value of Ab CGT was five times that of UGT708S6. Compared with Sc CGT1, the kcat/Km values of UGT708S6 for phloretin and 2-hydroxynaringenin were found to be 5.4 × 105 and 2.4 × 105 times higher respectively [45]. In comparison to Os CGT, the kcat/Km values of UGT708S6 for phloretin and 2-hydroxynaringenin were found to be 2.2 × 109 and 3.8 × 108 times higher, respectively [46]. In comparison to Fc CGT, when phloretin was used as the substrate, the kcat/Km value of Fc CGT was 3.8 × 1010 times greater than that of UGT708S6. When 2-hydroxynaringenin was used as the substrate, the kcat/Km value of Fc CGT was 2.7 × 109 times higher than that of UGT708S6 [47]. Therefore, we believe that UGT708S6 has catalytic ability in vivo. Furthermore, the catalytic properties of UGT708S6, the structural basis of substrate promiscuity and the catalytic mechanism involved in the formation of flavonoid C-glycosides were also elucidated in this study. However, the catalytic mechanism of Dca CGT does not be reported.

For CGTs, one of the key factors affecting catalytic activity is the position of the sugar acceptors in the binding pocket When phloretin (1) was used as the substrate, the hydrogen bond between Arg271 and hydroxy group at the 4-position of phloretin (1), brought the nucleophilic aromatic carbon in close proximity to the UDP-Glc hetero carbon at the appropriate position to initiate the catalytic reaction. The Met88 contributed to the formation of the substrate-binding pocket (Fig. 6B). Upon mutating the arginine at position 271 to glycine and histidine, Gly271 and His271 were located at distances of 5.9 Å and 5.1 Å from the anomeric carbon of UDP-Glc respectively (Fig. 6D, E). In comparison, the wild type Arg271 was located at a distance of 3.6 Å (Fig. 6B). The increased distance between UDP-Glc and these residues led to a decrease or even a disappearance of catalytic activity (Fig. 6D, E). Conversely, the mutation of methionine at position 88 to valine led to the hydrogen bond distance from 3.6 Å to 3.3 Å (Fig. 6C). The shorter hydrogen bond distance was more conducive for the reaction to take place, leading to increased catalytic activity of M88V (Fig. 7D). Previously, Gg CGT from Glycyrrhiza glabra has been reported to catalyze the di-C-glucosylation of phloretin [48]. For further analysis, we studied the crystal structures of Gg CGT in complex with UDP/phloretin, and UDP/nothofagin, then compared it with our molecular docking results. As reported by Zhang et al., benefit from the spacious binding pocket, Gg CGT can either attach different substrates, and catalyze the di-C-glycosylation. Similar to His27 in Gg CGT, His21 in UGT708S6 initiates the glycosylation reaction through deprotonation. Unlike Gly389 in Gg CGT, the Asp374 in UGT708S6 has a bulkier side chain, which does not provide ample space to accommodate single-carbon glycoside compounds as substrates for the second step of di-C-glycosylation reaction.

When 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) was used as the substrate, Arg271 and Met88 still play an important role, while the aspartic acid at position 374 was able to form a hydrogen bond with the hydroxy group at the 7-position of 2-hydroxynaringenin (14). The combined action of Arg271 and Asp374 facilitated the approach of the aromatic carbon at position 6 towards the anomeric carbon of UDP-Glc, promoting the glycosylation reaction (Fig. 6F). When the arginine at position 271 was mutated to glycine or histidine, the distance between the aromatic carbon at position 6 and the anomeric carbon of UDP-Glc changed from 4.3 Å to 5.6 Å (R271H) and 6.1 Å (R271G) respectively (Fig. 6H, I). The increased distance made C6 less likely to be the optimal site for nucleophilic attack, which was not conducive to the deprotonation of the adjacent hydroxyl group and the progression of the catalytic reaction (Fig. 7D). Despite the mutation of methionine at position 88 to valine, the spatial orientation of the substrate was not significantly altered due to the hydrogen bonding from Arg271 and Asp374. The catalytic activity of the M88V towards 2-hydroxynaringenin (14) did not increase (Fig. 7D). These imply that modifying the properties of the side chains at critical amino acid positions can induce changes in the spatial configuration of the binding pocket and the interactions with the substrate. These alterations can impact the enzyme’s binding orientation with the substrate, resulting in a functional transformation of the enzyme [21].

The formation of O-glycoside or C-glycoside is influenced by the position of sugar acceptors in the binding pocket [41]. Additionally, the size of the active pocket is an important factor to determine the catalytic properties of C- and O-glycosylation. Mutants exhibited smaller binding pockets compared to the wild-type (UGT708S6: 3336.45 Å3, M88V: 2860.03 Å3, R271G: 2825.28 Å3, R271H: 2861.89 Å3). These mutants showed the ability to form new O-glycosides but had reduced catalytic activity towards C-glycosides (Fig. 7). The findings indicated that a wider binding pocket favors the generation of C-glycosides, which is crucial for the biosynthesis of D. catenatum flavonoids. Through targeted mutagenesis, we identified key amino acid residues that affect enzyme activity and catalytic efficiency, providing a valuable foundation for studying the mechanism of plant glycosyltransferases.

Conclusion

In this study, we characterized a new glycosyltransferase, UGT708S6, isolated from Dendrobium catenatum flowers. Our findings reveal that UGT708S6 is a cytoplasm-localized protein, consistent with the localization of most UGTs in plants. Under various stress conditions such as JA and cold stresses, expression of UGT708S6 showed significant up-regulation, suggesting its crucial role in stress response mechanisms. Transcriptome analysis indicated that UGT708S6 exhibited highest expression levels in the flower and pollen tissues, aligning with the presence of flavonoid glycosides in these locations. UGT708S6 demonstrated dual catalytic activity C-glycosylation and O-glycosylation of flavonoids, displaying promiscuity towards different sugar acceptors and donors. Structural analysis identified key active sites that determine the catalytic specificity of UGT708S6. Site-directed mutagenesis was utilized to alter the catalytic efficiency of UGT708S6, leading to the production of new O-glycosides. Specifically, we pinpointed Arg271 as a key residue that significantly affects the enzymatic function of UGT708S6. This research offers valuable insights into the control of flavonoid metabolism and elucidates the mechanisms involved in glycosylation reactions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- UGT

UDP-glycosyltransferase

- CGT

C-glycosyltransferase

- D. catenatum

Dendrobium catenatum

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- JA

Jasmonic acid

- P1

Sclerotium delphinii

- SRA

Sequence Read Archive

- UDP-Glc

Uridine diphosphate glucose

- UDP-Rha

Uridine diphosphate rhamnose

- UDP-Xyl

Uridine diphosphate xylose

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

- pI

Isoelectric point

Author contributions

L.Z., LY.Y., K.X. and XF.Z. conceived the original research; LY.Y., K.He. and Yu.W. designed and performed experiments and analyzed the data; Yun.W., K.Hao., JB.Y., and YX.Z. assisted with the experiments; MX.C., QX.Y. and YH.S. participated in data collection, LY.Y. and K.He. wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (No.82225047), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82170274), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2022YFC3501703). Natural Science Foundation of the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (Project number: 24ZR1480900). The Major Science and Technology Projects of Breeding New Varieties of Agriculture in Zhejiang Province (No.2021C02074).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Luyao Yu, Kun He and Yu Wu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ke Xu, Email: kx2129@tongji.edu.cn.

Xinfeng Zhang, Email: zhangxf73@163.com.

Lei Zhang, Email: starzhanglei@aliyun.com.

References

- 1.Plaza M, Pozzo T, Liu J, Gulshan Ara KZ, Turner C, Nordberg Karlsson E. Substituent effects on in vitro antioxidizing properties, stability, and solubility in flavonoids. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(15):3321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermejo-Bescos P, Jimenez-Aliaga KL, Benedi J, Martin-Aragon S. A Diet Containing Rutin ameliorates Brain Intracellular Redox Homeostasis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4863–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyal J, Verma PK. An overview of Biosynthetic Pathway and therapeutic potential of Rutin. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2023;23(14):1451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karadeniz F, Oh JH, Seo Y, Yang J, Lee H, Kong CS. Quercetin 3-O-Galactoside isolated from Limonium Tetragonum inhibits melanogenesis by regulating PKA/MITF signaling and ERK Activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3064–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antunes-Ricardo M, Guardado-Felix D, Rocha-Pizana MR, Garza-Martinez J, Acevedo-Pacheco L, Gutierrez-Uribe JA, Villela-Castrejon J, Lopez-Pacheco F, Serna-Saldivar SO. Opuntia ficus-indica Extracisorhamnetinmnetin-3-O-Glucosyl-Rhamndiminishminish growthGrowcolon cancerCcells xenograftedrafted in Isuppressedrmiced Mice througactivationvatiapoptosispintrinsicrpathwayathway. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2021;76(4):434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji L, Shi W, Li Y, He J, Xu G, Qin M, Guo Y, Ma Q. Systematic Identification, Fragmentation Pattern, And Metabolic Pathways of Hyperoside in Rat Plasma, Urine, And Feces by UPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS. J Anal Methods Chem 2022, 2022:2623018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Terao J. Potential role of Quercetin glycosides as anti-atherosclerotic food-derived factors for Human Health. Antioxid (Basel). 2023;12(2):258–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Zhang Y, Sheng H, Liang C, Liu H, Moran Guerrero JA, Lu Z, Mao W, Dai Z, Liu X, et al. Hyperoside suppresses renal inflammation by regulating macrophage polarization in mice with type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Front Immunol. 2021;12:733808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molimau-Samasoni S, Woolner VH, Foliga ST, Robichon K, Patel V, Andreassend SK, Sheridan JP, Te Kawa T, Gresham D, Miller D, et al. Functional genomics and metabolomics advance the ethnobotany of the Samoan traditional medicine matalafi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(45):e2100880118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren Z, Ji X, Jiao Z, Luo Y, Zhang GQ, Tao S, Lei Z, Zhang J, Wang Y, Liu ZJ, et al. Functional analysis of a novel C- glycosyltransferase in the orchid Dendrobium catenatum. Hortic Res. 2020;7:111–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Zhang S, Gao B, Qian Z, Liu J, Wu S, Si J. Identification and quantitative analysis of phenolic glycosides with antioxidant activity in methanolic extract of Dendrobium catenatum flowers and selection of quality control herb-markers. Food Res Int. 2019;123:732–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Si J, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Liu J, Liu Z. [Herbal textual research on relationship between Chinese medicineShihu (Dendrobium spp.) and Tiepi Shihu (D. Catenatum)]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi = Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi = China J Chin Materia Med. 2017;42(10):2001–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Śliwiński T, Kowalczyk T, Sitarek P, Kolanowska M. Orchidaceae-Derived Anticancer agents: a review. Cancers. 2022;14(3):754–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi L, Shi Y, Li C, Liu J, Chong S, Lim K, Si J, Han Z, Chen D. Glucomannan in Dendrobium catenatum: Bioactivities, Biosynthesis and Perspective. Genes. 2022;13(11):1957–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie L, Deng Z, Zhang J, Dong H, Wang W, Xing B, Liu X. Comparison of Flavonoid O-Glycoside, C- Glycoside and Their Aglycones on Antioxidant Capacity and Metabolism during In Vitro Digestion and In Vivo. Foods. 2022;11(6):882–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori T, Kumano T, He H, Watanabe S, Senda M, Moriya T, Adachi N, Hori S, Terashita Y, Kawasaki M, et al. C-Glycoside metabolism in the gut and in naidentificationcation, characterization, structural analyses and distribution of C-C bond-cleaving enzymes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tremmel M, Kiermaier J, Heilmann J. In Vitro Metabolisixof Six C-Glycoflavonoidsonoids from Passiflora incarnata L. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6566–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. Glycosyltransferases: structures, functions, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:521–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George Thompson AM, Iancu CV, Neet KE, Dean JV, Choe JY. Differences in salicylic acid glucose conjugations by UGT74F1 and UGT74F2 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tegl G, Nidetzky B. Leloir glycosyltransferases of natural product C- glycosylation: structure, mechanism and specificity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2020;48(4):1583–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutmann A, Nidetzky B. Switching between O- and C- glycosyltransferase through exchange of active-site motifs. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(51):12879–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M, Wang D, Li Y, Li X, Zong G, Fei S, Yang X, Lin J, Wang X, Shen Y. Crystal Structures of the C-Glycosyltransferase UGT708C1 from Buckwheat Provide Insights into the Mechanism of C- Glycosylation. Plant Cell. 2020;32(9):2917–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cozzetto D, Jones DT. Computational methods for annotation transfers from sequence. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1446:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou Y, Li J, Li Y, Dong Z, Xia Q, Yuan YA. Crystal structure of Bombyx mori arylphorins reveals a 3:3 heterohexamer with multiple papain cleavage sites. Protein Sci. 2014;23(6):735–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Fan S, Chen R, Xie K, Yin S, Sun L, Liu J, Yang L, Kong J, Yang Z, et al. Probing and Engineering Key residues for Bis-C-glycosylation and promiscuity of a C-Glycosyltransferase. ACS Catal. 2018;8(6):4917–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Chen J, Feng J, Wang Y, Li S, Xiao Y, Diao Y, Zhang L, Chen W. Tandem UGT71B5s catalyze Lignan Glycosylation in Isatis Indigotica with substrates Promiscuity. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:637695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen QY, Chen DH, Shi Y, Si WS, Wu LS, Si JP. [Occurrence regularity of Dendrobium catenatum southern blight disease]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2019;44(9):1789–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou LH, Wan X, Deng H, Zheng BQ, Li BJ, Wang Y. RNA-seq transcriptomic profiling of crassulacean acid metabolism pathway in Dendrobium catenatum. Sci Data. 2018;5:180252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schöning-Stierand K, Diedrich K, Fährrolfes R, Flachsenberg F, Meyder A, Nittinger E, Steinegger R, Rarey M. ProteinsPlus: interactive analysis of protein-ligand binding interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones P, Vogt T. Glycosyltransferases in secondary plant metabolism: tranquilizers and stimulant controllers. Planta. 2001;213(2):164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogt T, Jones P. Glycosyltransferases in plant natural product synthesis: characterization of a supergene family. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5(9):380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Najafi J, Brembu T, Vie AK, Viste R, Winge P, Somssich IE, Bones AM. PAMP-INDUCED SECRETED PEPTIDE 3 modulates immunity in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(3):850–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ying Z, Ling-Shang WU, Qiu-Yan C, Mei-Chen S, Cong LI, Jin-Ping SI. [Screening of endophytic fungi against southern blight disease pathogen-sclerotium delphinii in Dendrobium Catenatum]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2020;45(22):5459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu W, Yan C, Li L, Liu Z, Liu S. Studies on the flavones using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1047(2):213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XX, Li XB, Peng CS. [Comprehensive mass spectrum analysis of two flavone-6,8-C-di-glycosides and its application by high resolution electrospray ionization tandem mass spectroscopy in both negative and positive ion modes]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2019;44(22):4880–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiao X, He WN, Xiang C, Han J, Wu LJ, Guo DA, Ye M. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of flavonoids in Spirodela polyrrhiza by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. Phytochem Anal. 2011;22(6):475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen Z, Zhang Z-M, Zhong L, Fan J, Li M, Ma Y, Zhou Y, Zhang W, Guo B, Chen B, et al. Directed Evolution of a plant glycosyltransferase for chemo- and regioselective glycosylation of pharmaceutically significant flavonoids. ACS Catal. 2021;11(24):14781–90. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang J, Pang C, Fan S, Song M, Yu J, Wei H, Ma Q, Li L, Zhang C, Yu S. Genome-wide analysis of the family 1 glycosyltransferases in cotton. Mol Genet Genomics. 2015;290(5):1805–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahimi S, Kim J, Mijakovic I, Jung KH, Choi G, Kim SC, Kim YJ. Triterpenoid-biosynthetic UDP-glycosyltransferases from plants. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37(7):107394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He JB, Zhao P, Hu ZM, Liu S, Kuang Y, Zhang M, Li B, Yun CH, Qiao X, Ye M. Molecular and structural characterization of a promiscuous C-Glycosyltransferase from Trollius Chinensis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58(33):11513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiromoto T, Honjo E, Noda N, Tamada T, Kazuma K, Suzuki M, Blaber M, Kuroki R. Structural basis for acceptor-substrate recognition of UDP-glucose: anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase from Clitoria ternatea. Protein Sci. 2015;24(3):395–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bidart GN, Putkaradze N, Fredslund F, Kjeldsen C, Ruiz AG, Duus JO, Teze D, Welner DH. Family 1 Glycosyltransferase UGT706F8 from Zea mays Selectively Catalyzes the Synthesis of Silibinin 7-O-beta-d- Glucoside. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022;10(16):5078–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie K, Zhang X, Sui S, Ye F, Dai J. Exploring and applying the substrate promiscuity of a C- glycosyltransferase in the chemo-enzymatic synthesis of bioactive C- glycosides. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5162–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ni R, Liu XY, Zhang JZ, Fu J, Tan H, Zhu TT, Zhang J, Wang HL, Lou HX, Cheng AX. Identification of a flavonoid C-glycosyltransferase from fern species Stenoloma Chusanum and the application in synthesizing flavonoid C-glycosides in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2022;21(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brazier-Hicks M, Evans KM, Gershater MC, Puschmann H, Steel PG, Edwards R. The C-glycosylation of flavonoids in cereals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(27):17926–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ito T, Fujimoto S, Suito F, Shimosaka M, Taguchi G. C-Glycosyltransferases catalyzing the formation of di-C- glucosyl flavonoids in citrus plants. Plant J. 2017;91(2):187–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang M, Li F-D, Li K, Wang Z-L, Wang Y-X, He J-B, Su H-F, Zhang Z-Y, Chi C-B, Shi X-M, et al. Functional characterization and structural basis of an efficient Di-C-glycosyltransferase from Glycyrrhiza glabra. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(7):3506–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.