Abstract

Halomonas species are renowned for their production of organic compatible solutes, particularly ectoine. However, the identification of key regulatory genes governing ectoine production in Halomonas remains limited. In this study, we conducted a combined transcriptome-proteome analysis to unveil additional regulatory genes influencing ectoine biosynthesis, particularly under ultraviolet (UV) and salt conditions. NaCl induction resulted in a 20-fold increase, while UV treatment led to at least 2.5-fold increases in ectoine production. The number of overlapping genes between transcriptomic and proteomic analyses for three comparisons, i.e., non-UV with NaCl (UV0-NaCl) vs. non-UV without NaCl (UV0), UV strain 1 (UV1-NaCl) vs. UV0-NaCl, and UV strain 2 (UV2-NaCl) vs. UV0-NaCl were 137, 19, and 21, respectively. The overlapped Gene Ontology (GO) enrichments between transcriptomic and proteomic analyses include ATPase-coupled organic phosphonate, phosphonate transmembrane transporter activity, and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport complex in different comparisons. Furthermore, five common genes exhibited different expression patterns at mRNA and protein levels across the three comparisons. These genes included orf01280, orf00986, orf01283, orf01282 and orf01284. qPCR verification confirmed that three of the five common genes were notably under-expressed following NaCl and UV treatments. This study highlighted the potential role of these five common genes in regulating ectoine production in Halomonas strains.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-024-11003-9.

Keywords: Ectoine, Halomonas, Transcriptome, Proteome, Ultraviolet, Salt treatments

Introduction

Gram-negative Halomonas species are halophilic bacteria thriving in saline or hypersaline environments [1]. Halomonas are renowned as prominent producers of organic compatible solutes, especially 1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2-methyl-4-pyrimidine carboxylic acid (ectoine). Ectoine can facilitate the osmotic equilibrium of the cytoplasm with the surrounding medium. Among compatible solutes, ectoine is used as a protector of cells and tissues. As a stabilizer of enzymes and antibodies, it is not only essential for extremophiles to survive in extreme environments but also widely used in cosmetic and medical industries. Skin cares containing ectoine are warmly welcomed in cosmetic preparation. Given the protective role of ectoine against noxious extracellular stimulus, e.g., ultraviolet (UV) rays, mutant strains subjected to UV mutagenesis may exhibit increased ectoine production [2]. So far, various species (e.g., H. ventosae, H. elongate, H. boliviensis, H. salina, and H. hydrothermalis) can be used to synthesize ectoine, and there is a huge demand for facilitating the mass over-production of ectoine.

Ectoine was traditionally produced by Halomonas strains (e.g., H. elongate and H. campaniensis) through a “bacterial milking” process, of which the marked feature is using a high-salt medium to stimulate ectoine biosynthesis and then excreting ectoine into a low-salt medium by osmotic shock [3]. The biosynthesis of ectoine can be enhanced by glutamate (used as a source of carbon and nitrogen) in response to salt stress, and practice, sodium L-glutamate is a useful agent to promote ectoine synthesis. Theoretically, ectoine biosynthesis is closely related to the L-aspartate biosynthetic pathway and relies on the highly conserved gene cluster operons ectA, B, and C [4, 5].

First, L-aspartate is converted by LysC (aspartate kinase) and Asd (aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase) to L-aspartate-β-semialdehyde, which is regarded as ectoine precursor substrate. Then, with the contribution of L-diaminobutyrate aminotransferase (EctB), L-diaminobutyrate acetyltransferase (EctA) and tetrahydropyrimidine synthase (EctC), ectoine is synthesized. In addition, tetrahydropyrimidine hydroxylase (EctD), can convert ectoine into hydroxyectoine [6].

In this study, we used the H. campaniensis strain XH26 to optimize the ectoine synthesis. This strain can accumulate compatible solute ectoine at the extracellular level of 0.43 ± 0.01 g/L when no salt stress was given, and after UV treatments, the output of ectoine was increased significantly. To further identify the key genes from both mRNA and protein levels that were responsible for ectoine, we performed transcriptomic and proteomic combined analysis to uncover the key genes (as well as the essential pathways and networks) regulating ectoine biosynthesis and potentially involved in the adaptation of both salt and UV mutagenesis treatments. The presented data aims to demonstrate the differentially expressed genes in comparisons between mutant strains with UV vs. NaCl and non-UV strains vs. NaCl. These results, derived from the same key gene list, suggested that these genes are associated with NaCl treatment but not specifically with UV mutagenesis treatment. This study provided a promising strategy for the improvement of ectoine fermentation in H. campaniensis.

Methods

Strains

Wild-type H. campaniensis strain XH26 (CCTCCM2019776) in this study was isolated from Xiaochaidan Salt Lake in the Chaidamu Basin, China (37.8°N, 94.3°E). The isolation and characterization of the XH26 strain were previously described [2]. Two mutant strains, i.e., UV mutant strain 1 and UV mutant strain 2 with high ectoine yield were obtained by classic UV mutagenesis treatments for different rounds of exposure times (8 rounds and 16 rounds), namely UV1 and UV2, respectively. The culture medium for ectoine accumulation (CMEA) contained 0.1 M MgSO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2 (w/v), 0.25 M KCl, 30 mM Sodium L-Glutamate, and 12.5 g/L (w/v) Casein enzymatic hydrolysate (Solarbio Life Science, China). For the NaCl treatment, 1.5 M NaCl was added to the CMEA medium. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 8.0, and the temperature for ectoine fermentation was at 35 °C in a rotary shaker (120 rpm). Cell growth for 48 h was periodically determined by measuring OD600 using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (SP-754, Shanghai, China). In total, six strain types were applied: UV0 (non-UV, non-NaCl), UV0-NaCl (non-UV, 1.5 M NaCl), UV1 (UV mutant strain 1), UV1-NaCl (UV1, 1.5 M NaCl), UV2 (UV mutant strain 2), and UV2-NaCl (UV2, 1.5 M NaCl). Three biological replicates in each group were used for high-throughput analysis of transcriptome and proteome.

Multiple rounds of ultraviolet radiation treatments

The wild-type strain XH26 was activated and grown in 150 mL of CMEA medium for 14 to 16 h, as previously reported [2]. Cultures were then diluted with 0.9% NaCl to achieve bacterial cell concentrations of 106 to 108 CFU/mL (Fig. 1). Bacterial suspensions (20 mL) were then distributed on a sterile glass plate (90 mm diameter) and exposed to a UV-C lamp at a wavelength of 253.7 nm (220-volt, 25-watt). The distance between the glass plate and the UV lamp was adjusted to 30 cm [7]. Exposure times of 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 s were evaluated. Next, 50 µL of bacterial suspensions treated for different times were spread on CMEA agar plates, with duplicates used for each time point. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 35 °C in the dark to prevent photoreactivation. Mutant colonies were identified based on their sizes and growth rates defined as increased rates of OD values recorded every 10 min. The OD600 value for each strain was measured using a UV spectrophotometer (Biochrom WPA Lightwave II, Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK) with appropriate dilution. Colonies were subsequently transferred to a liquid CMEA medium. Mutants were then isolated based on their ectoine content production and biomass productivity. At least eight rounds of UV exposure for one original strain were conducted using the above procedure. Strains treated with UV mutagenesis and NaCl were isolated through in vitro serial sub-culturing for 40 d. For phosphate treatment, NaH2PO4·2H2O (10.0 g L-1) was added to the CMEA medium used for the wild-type strain XH26. The strains were then harvested at 4 d and cultivated in CMEA medium.

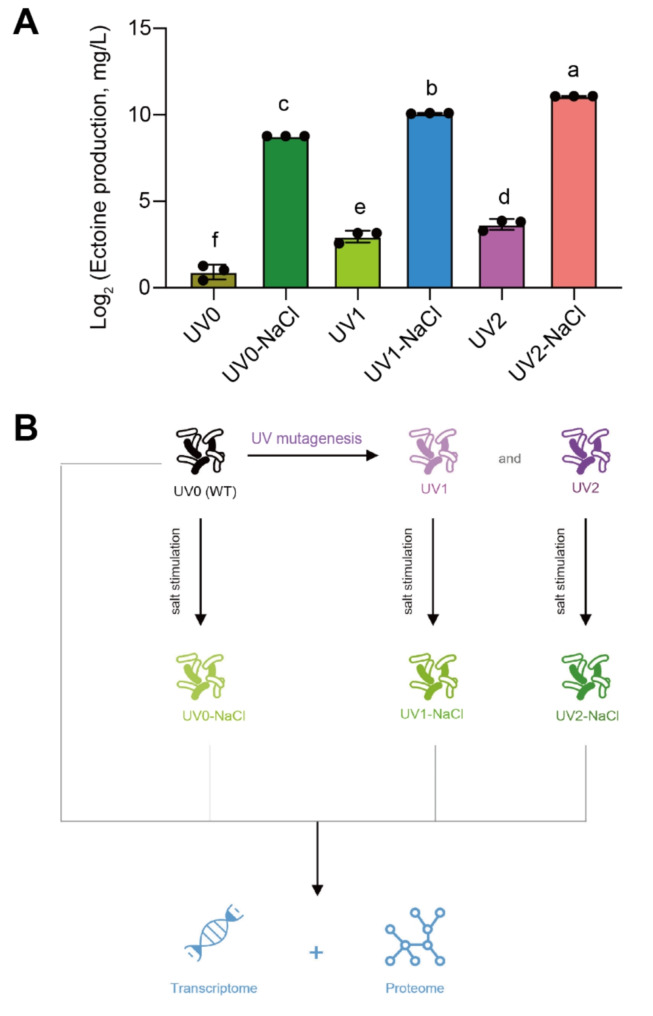

Fig. 1.

The workflow of this study and the increased ectoine production under salt stimulation and ultraviolet (UV) treatments in Halomonas campaniensis. (A) ectoine production in XH26 exposed to salt and UV treatment. Different letters represent significant differences in XH26 subjected to different treatment groups based on one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. n = 3. (B) The research workflow diagram. Six types of strains were applied: UV0 (non-UV and non-NaCl); UV0-NaCl (non-UV and 1.5 M NaCl); UV1 (UV mutant strain 1); UV1-NaCl (UV1-1.5 M NaCl); UV2 (UV mutant strain 2); UV2-NaCl (UV2-1.5 M NaCl)

Phosphate feeding experiment

To validate the causal relationship between cellular phosphate status and ectoine production, we have conducted an experiment involving the addition of H2PO4 − 1 to analyze ectoine production under phosphate-sufficient conditions. The wild-type strain XH26 was activated and grown in 150 mL of CMEA medium plus either phosphate sufficient conditions with NaH2PO4·2H2O (10.0 g L− 1) or control condition without phosphate supply for 14 to 16 h. Three independent experiments were conducted.

HPLC detection of ectoine production

For each sample, a total of 1.5 mL of fermentation liquor was harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 5 min. The pellets were suspended in ethanol solution (90%, v/v) with vigorous shaking for 2 min, and then smashed for 5 min with a high-speed tissue grinder (OSE-Y50, Tiangen Ltd., China). The ethanol extract was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-mm filter. The concentration of the ectoine extracts was determined by HPLC analysis, using an Aligent Technologies HPLC (1260 Series, USA) system. Chromatography was performed at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with acetonitrile/ultrapure water (4/1, v/v) as the mobile phase at 30 °C. The presence of ectoine was monitored at 210 nm using a UV/VIS detector.

Determinations of antioxidant enzyme activities

Activities of malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) were determined using modified standard methods previously described [8]. For each sample, a total of 3 mL of fermentation liquor was harvested. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min at 4ºC. CAT and MDA activity measurements relied on the reaction solution (3 ml) of 56 mm H2O2 and 0.2 ml enzyme extract, with absorbance changes at 240 nm recorded every 30 s defining activity as µmol H2O2 reduced/min/g protein. POD activity was determined using the measurement of absorbance changes at 470 nm.

mRNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing

For each sample, 1.5 mL of fermentation liquor was harvested after 40 d of sub-culturing XH26. RNA extraction was conducted employing the Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA), while the RNA concentration was assessed with the NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Assessment of RNA degradation and contamination was performed using 1% agarose gels. Purity was assessed utilizing the Nano-Photometer spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA), while RNA integrity was measured with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit. Each sample utilized 1.5 µg of RNA as input material for RNA sample preparations. The sequencing libraries were created using the NEB Next Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). Index codes were incorporated to assign sequences to individual samples. These index-coded samples were then clustered using a Bot Cluster Generation System with the HiSeq 4000 PE Cluster Kit (Illumina, USA) [9]. Following cluster generation, the libraries underwent sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads.

The quality of the RNA-seq data (fastq files) was evaluated using the FastQC software [10]. Adaptor and low-quality read trimming from the raw RNA-seq reads were performed using the trim_galore software [11]. The RNA-seq analysis was conducted using the STAR software (version 2.5.3a) [12], and aligned against the H. campaniensis reference genome obtained from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/taxonomy/213554/. The Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) values were computed using cutlinks software (v2.2.1) [13]. This was done to assess the relative abundance of genes across various comparisons of UV and NaCl-treated samples. The expression values were normalized using DeSeq2 with default normalization algorithms [14].

Protein extraction and proteomic analysis

For each sample, 1.5 mL of fermentation liquor was harvested after 40 d of sub-culturing XH26. The protein extraction procedure for H. campaniensis strain XH26 followed an improved TCA method [15]. Subsequently, the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method [16]. The protein solution was either utilized immediately for subsequent experiments or stored as a protein pellet at − 80 °C until use.

The proteins underwent initial treatment with 10 mM DTT at 37 °C for 2.5 h, followed by alkylation with 50 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) for 30 min at 37 °C in darkness. For trypsin digestion, the samples were incubated with a urea solution at a concentration of 1.5 M. Subsequently, the proteins underwent digestion with trypsin for 18 h. Following digestion, peptides were subjected to desalted using an SPE C18 column (Waters WAT051910) and then dried under vacuum. The treated peptides were analyzed using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with an easy nLC-1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In summary, the peptides were initially loaded onto the RP-C18 column (Thermo EASY column SC001 traps) and separated using an analytical column (EASY column SC200 150 μm×100 mm, RP-C18) at a flow rate of 0.3 µL/min. This separation was achieved using a linear gradient ranging from 0 to 55% solvent B (0.1% formic acid in 84% acetonitrile) over 110 min, followed by an increase to 100% solvent B over 8 min. The system then remained at 100% solvent B for 2 min. The resulting peptides were analyzed using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). During MS scans, the m/z (mass-to-charge ratio) scan ranged from 350 to 1800. Survey scans were acquired at a resolution of 60,000 at 210 m/z, while the resolution for HCD spectra was set to 12,000 at 200 m/z. The DIA proteome analysis was conducted by APT Biotech Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). The mass spectrometry data were analyzed using MaxQuant software featuring the integrated Andromeda search engine (v. 1.3.0.5). The search was conducted against the protein sequence database available at https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000011651.fasta.

Identification of DEGs and DAPs

For the proteome and transcriptome, both differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis and differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) were performed according to the following standards. A DEG was regarded as a gene with a fold‑change (FC) ≥ 2 or ≤ 0.5 and the adjusted p < 0.05. The volcanic plots were produced to present DAPs and DEGs in proteome and transcriptome analysis, respectively. Furthermore, a Venn diagram was drawn to analyze the intersection between DEGs and DAPs in different comparisons.

GO functional and KEGG pathway enrichments

Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment were analyzed based on the list of both DEGs and DAPs from different comparisons of UV and NaCl treatments. The enrichment p-value of the Pathway ID was calculated based on Fisher’s exact test. Terms with a p-value < 0.05 and gene counts ≥ 2 were selected as a differential term. The top-ranked GO and KEGG terms were presented as column charts.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

The common DEGs of three comparisons (appeared in two comparisons) were used to construct the PPI network using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database (http://www.string-db.org). The online tool of multiple proteins (organism: Halomonas) was used for batch analysis, and the active interaction source included all terms, including text mining, experiments, databases, co‑expression, neighborhood, gene fusion, and co‑occurrence. The criterion of node connection was the combined ≥ 0.4.

Verification of common DEGs by qPCR

The five common DEGs of three comparisons were verified by real-time qPCR, and the primers were listed (Table S1). Total RNA was extracted using the TrizolTM Reagent (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration was determined using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer. After reverse transcription with the PrimeScrip RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time, Takara) and the microRNA RT-PCR system (BioTNT, A2030A001-120T, China), cDNA was obtained and stored at -20 °C. The reaction volume included 10 µL UNICONTM qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix, 1 µL of the primer mixture (200 nM), 6 µL of cDNA templates, and 6 µL of RNase-free ddH2O. The thermocycler program was as follows: 3 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, and 20 s at 65 °C; 30 s at 72 °C. The relative expression mRNA was calculated using the comparative method with 16 S rRNA as the reference gene. All reactions were run in triplicate.

Results

Increased ectoine production by UV and NaCl stimulation

Halomonas are known as prominent producers of organic compatible solutes, especially ectoine. In this study, we obtained two mutant strains of Halomonas campaniensis induced by heavy UV mutagenesis and subsequent selection for salt-stress resistance. Ectoine production and antioxidant enzyme activities were then measured in Halomonas XH26 samples subjected to both UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). In the UV0-NaCl strain, ectoine yield increased more than 20-fold compared to UV0. For the UV1 and UV2 mutant strains, ectoine production increased by 2.5-fold and 4-fold, respectively (Fig. 1A). Compared to UV0, SOD activities in XH26 induced by UV increased at least 30% in both mutant strains (Fig. S1A). In contrast, compared to UV0, the OD values, as well as CAT and CAT activities, were similar or decreased in the various comparisons of UV and NaCl-treated samples (Fig. S1 B-D; Table S2).

Next, we sequenced the ectABC gene cluster in the two mutant strains of Halomonas to investigate potential mutations in the genomic regions of the ectoine biosynthetic genes. Results showed that the sequences of the ectABC cluster (including CDS and promoter region) were not changed (Figs. S2-S4).

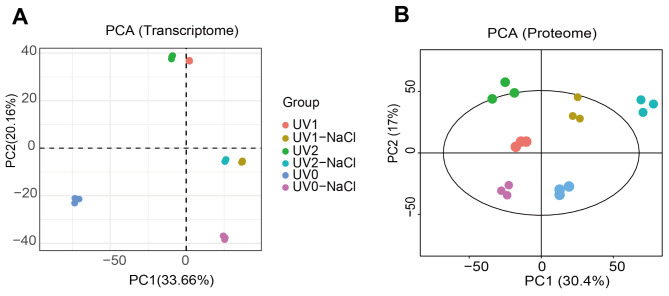

Samples quality analysis used for both transcriptome and proteome

Furthermore, to uncover some key genes underlying high ectoine yield under stimulation of both UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatment, we performed a transcriptomic and proteomic combined analysis following the pipelines indicated in Fig. 1B. Based on transcriptomes, we found that the log10FPKM values maintained at around 2 across different samples subjected to UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments (Fig. S5). The samples in each group performed good relatedness with Pearson correlation index (R2) > 0.93, except for samples in the UV0 group (Fig. S6). Consistently, based on principal component analysis (PCA), we found that the samples for transcriptome within the group were clustered together (Fig. 2A). In addition, we found that the samples for proteome within the group were clustered together as well (Fig. 2B). This evidence suggested that the samples possess good repeatability within the group that was suitable for both transcriptomic and proteomic analysis.

Fig. 2.

Principal component analysis on transcriptome and proteomic in Halomonas campaniensis in combined treatments of both UV and NaCl. A, transcriptome data. B, proteomic data

Expression profiling of known ecotine biosynthetic and degradation genes

Next, we analyzed the abundance of known genes involved in ectoine biosynthesis and degradation process in Halomonas XH26 samples subjected to both UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments, using both transcriptomic and qPCR approaches. The results suggested that transcript abundances of the known EctABC cluster, i.e., diaminobutyric acid acetyltransferase (EctA, orf01884), diaminobutyric acid aminotransferase (EctB, orf01884), and ectoine synthase (EctC, orf01882) were enhanced by up to 4-fold in response to either UV mutagenesis (in both mutant strains) or NaCl treatment (Fig. S7A-C). The expression patterns of the three ectoine genes (EctA, EctB, and EctC) were similar, as shown by qPCR experiments, but with lower fold changes (Fig. S7D-F). In addition, transcript abundances of several genes involved in the ectoine degradation pathway including EctD (Ectoine dioxygenase, orf03200), EctR1 (MarR family transcription factor, orf01032), EctR2 (MarR family transcription factor, orf02069), Ask (Aspartate kinase, orf00786), DoeD1 (Diaminobutyrate-2-oxoglutarate transaminase, orf02975), DoeD2 (Diaminobutyrate-2-oxoglutarate transaminase, orf01883), and DoeC (Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, orf01624) were dramatically increased in Halomonas XH26 samples induced by both UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments, except for DoeA (Ectoine hydrolase, orf02985) (Fig. S8A-H).

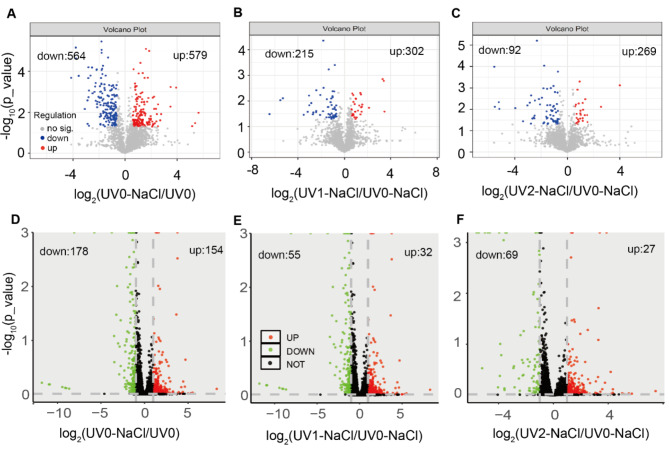

Identification of key genes underlying ectoine induced by both UV and NaCl

In the comparison of UV0-NaCl vs. UV0, there were 1,143 (564 downregulated, and 579 upregulated) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Fig. 3A; Table S3). In addition, there were less than 517 DEGs for the other two comparisons, i.e., UV1-NaCl vs. UV0-NaCl and UV2-NaCl vs. UV0-NaCl (Fig. 3B-C; Table S4-S5). Less numbers of downregulated DEGs than those of upregulated DEGs were found for the three comparisons (Fig. 3B-C). In addition, there were 332 differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) in comparisons of UV0-NaCl vs. UV0 (Fig. 3D; Table S6), and there were 87 and 96 DAPs for the other two comparisons, i.e., UV1-NaCl vs. UV0-NaCl and UV2-NaCl vs. UV0-NaCl (Fig. 3E-F and Table S7-S8). More numbers of downregulated DAPs than those of upregulated DAPs were found for the three comparisons, which was different from the cases performed in transcriptome (Fig. 3D-F).

Fig. 3.

Volcano plot analysis on differentially abundant protein and differentially expressed genes in different Halomonas strains in combined treatments of both UV and NaCl. A, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in UV0-NaCl versus UV0. B, DEGs in UV1-NaCl versus UV0-NaCl. C, DEGs in UV2-NaCl versus UV0-NaCl. D, differentially abundant proteins (DAPs) in UV0-NaCl versus UV0. E, DAPs in UV1-NaCl versus UV0-NaCl. F, DAPs in UV2-NaCl versus UV0-NaCl

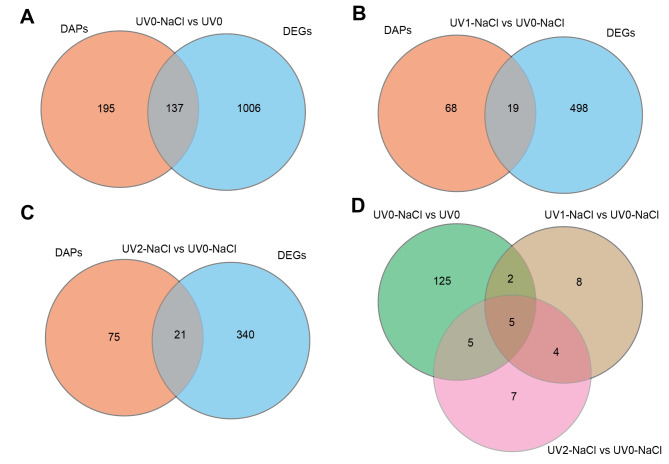

The overlapping genes between DEGs and DAPs in each comparison or across comparisons of UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments were further analyzed. We identified 137, 19, and 21 overlapping genes in the UV0-NaCl vs. UV0, UV1-NaCl vs. UV0-NaCl, and UV2-NaCl vs. UV0-NaCl comparisons, respectively (Fig. 4A-C). Furthermore, five common genes were identified with significant expression at both the mRNA and protein levels across all three different comparisons of UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram of common genes between DEGs and DAPs in Halomonas campaniensis under both UV and NaCl treatments. A, UV0-NaCl versus UV0. B, UV1-NaCl versus UV0-NaCl. C, UV2-NaCl versus UV0-NaCl. D, overlapped genes for the three combinations of UV and NaCl treatments

Expressed abundance analysis of the five common DEGs

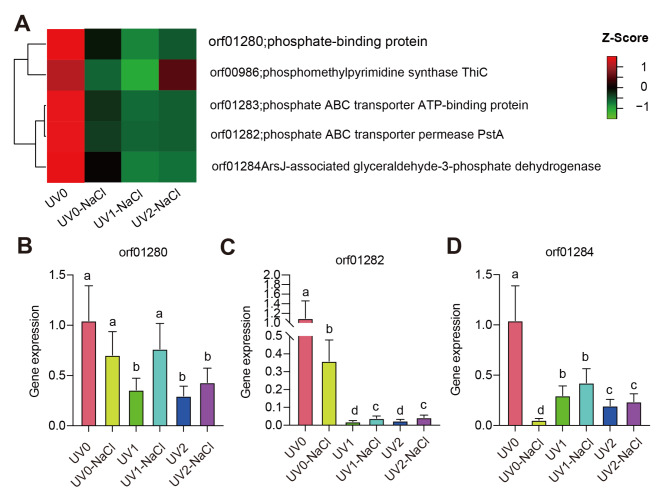

As mentioned above, we found five common DEGs that overlapped in both mRNA and protein levels across three comparisons of UV and NaCl treatments (Fig. 5A and Table S10), these five DEGs include orf01280 (phosphate-binding protein), orf00986 (phosphomethylpyrimidine synthase, ThiC), orf01283 (phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein), orf01282 (phosphate ABC transporter permease, PstA) and orf01284 (ArsJ-asociated glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). We found a higher abundance of genes in groups of UV0 than that of genes in groups of UV0-NaCl, UV1-NaCl, and UV2-NaCl (Fig. 5A), suggesting the decrease in the mRNA abundance of the five common DEGs in the two mutant strains exposed to UV mutagenesis (Fig. 6A-B). To further confirm the expression pattern of the five common DEGs, we performed qPCR (Fig. 5B–D). The results suggested that orf01282, orf01284, and orf01280 show higher expression in the UV0 group compared to other groups (Fig. 5B-D), which was consistent with the transcriptome dataset (Tables S3-S5). To better visualize the relationship between the five common DEGs, we constructed the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network generated by the STRING database. Results showed that orf01280, orf01282, orf01283, and orf01284 were in the same module of the PPI network (Fig. S9 and Table S11), suggesting the four common DEGs potentially worked together in the regulation of ectoine production.

Fig. 5.

Five common genes underlying ectoine changes in two mutant strains induced by NaCl. A, Heatmap representing the relative values of five common genes based on transcriptome analysis. B-D, relative gene expression levels of three common genes in XH26 exposed to UV and NaCl treatments. Different letters represented significant differences in XH26 subjected to different treatment groups based on one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. n = 3

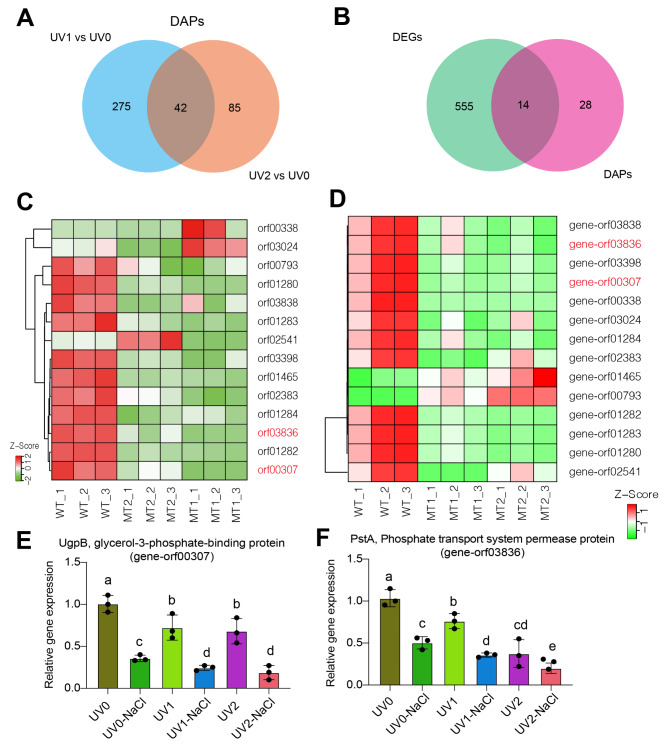

Fig. 6.

Identification and verification of overlapped DEGs from transcriptome and proteome datasets. A, Venn diagram showing the overlapped genes in comparisons of UV1 vs. UV0 and UV2 vs. UV0 absence of NaCl treatment based on proteomic analysis. B, Venn diagram showing the overlapped DEGs between transcriptome and proteomic analysis. C-D, Heatmap representing the changes of 14 overlapped DEGs in their abundance from transcriptome and proteomic analysis. E-F, Relative gene expression levels of orf00307 and orf03836. Different letters represented significant differences in XH26 subjected to different treatment groups based on one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. n = 3

Identification of key genes for ectoine production induced by UV absence of NaCl

Ecotine production was dramatically increased in the two UV-induced mutant strains, as mentioned above (Fig. 1A). To further identify key genes in XH26 induced by UV in the absence of NaCl treatment, we performed comparisons of UV1 vs. UV0 and UV2 vs. UV0 using both transcriptomic and proteomic analysis. In the transcriptomic analysis, we identified 373 upregulated DEGs that were common between the UV1 vs. UV0 and UV2 vs. UV0 comparisons (Fig. S10A). In contrast, we identified 197 down-regulated DEGs that were common between UV1 vs. UV0 and UV2 vs. UV0 (Fig. S10B). Among these DEGs (both up and down-regulated DEGs), GO analysis revealed significant enrichment in pathways to ion transmembrane transport, cation transmembrane transport, and cation transport (Fig. S10C). KEGG analysis showed significant enrichment in the metabolic pathways of the pentose phosphate pathway, arginine and proline metabolism, and biotin metabolism (Fig. S10D).

In the proteomic analysis, we identified 42 overlapping genes in the comparisons of UV1 vs. UV0 and UV2 vs. UV0 (Fig. 6A). Of these, 14 genes were found to overlap between transcriptomic and proteomic analysis (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the expression of most genes in this 14-gene list was downregulated in both mutant strains compared to UV0, as observed in both transcriptomic and proteomic analysis (Fig. 6C-D). The expression levels of UgpB (glycerol-3-phosphate-binding protein) and PstA (phosphate transport system permease protein) were confirmed by qPCR, (Fig. 6E-F), consistent with the transcriptome dataset (Fig. 6D).

Promoted effects of ectoine production by phosphate

The evidence strongly suggested a close relationship between phosphate transporters and ectoine production. To confirm this, we conducted a phosphate-feeding experiment and found that ectoine production increased by 20% with phosphate treatment (Fig. S11A). In addition, the expression levels of the phosphate transporters genes showed similar or significantly reduced values under phosphate-sufficient conditions (Fig. S11B-F).

Discussion

Halomonas species are known for their significant production of ectoine an organic compatible solute valuable for various applications. However, the impact and mechanisms of UV and NaCl treatments on ectoine production remain relatively underreported. This study involved the creation of two mutant Halomonas strains via heavy UV mutagenesis and subsequent selection for salt-stress resistance. Our findings distinctly demonstrated the promotive effects of both UV and NaCl treatments on ectoine production. Both transcriptome and proteome analyses, specifically in strain XH26 of H. campaniensis, revealed enriched pathways related to phosphorate transporters and enzymes in DEGs and DAPs. Notably, five common DEGs across comparisons were identified, emphasizing their roles in regulating ectoine production.

Ectoine holds significant potential across various fields due to its ability to balance osmotic pressure, hydrate lipid membranes, and stabilize DNA structure [17–19]. Previously, different strategies have been developed to increase ectoine production, such as optimizing the agitation speed and medium composition [20, 21], and in-frame deletion of genes encoding ectoine hydroxylase (EctD) and ectoine hydrolase DoeA [22]. In this study, we successfully attempted to apply UV mutagenesis to stimulate ectoine production in the two mutant strains of H. campaniensis and it increased the output of ectoine from 1.93 mg/L to 2,167 mg/L (Fig. 1A). In the two UV-induced mutant trains, the expression levels of UgpB (glycerol-3-phosphate-binding protein) and PstA (phosphate transport system permease protein) were strongly inhibited compared to UV0, with even greater inhibition observed under NaCl simulations (Fig. 6E-F). The inhibitory effects were observed at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6C-D). PstA was responsible for phosphate internalization under phosphate-limited conditions [23], while UgpB played a major role in glycolysis and phospholipid biosynthesis in the cell [24], suggesting that the phosphate transport system was inhibited in both mutant strains and further suppressed by NaCl stimulations.

The production of ectoine can be affected by both biosynthesis and biodegradation, whereas ectoine degradative genes are not necessary for ectoine biosynthesis because the majority of ectoine producers do not possess ectoine degradative genes. In the aspect of biosynthesis, ectoine production can be affected by EctA, EctC, EutA, EutB, L-lysine biosynthesis, and EutC (EutC may be more important than other biosynthesis enzymes) [3, 25]. Interestingly, we found no changes in the sequences of the ectABC cluster, including CDS and promoter regions (Supporting Datasets 1 and 2). However, the expression of ectABC cluster genes was significantly enhanced by NaCl in both mutant strains (Fig. S7D-F), suggesting that factors other than structural changes in the ectABC cluster may be involved in promoting ectoine production. In the aspect of ectoine hydrolase regulation, ectoine hydrolase putative ectoine hydrolase (DoeA), Nα-acetyl-L-2,4-diaminobutyrate deacetylase (DoeB), aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (DoeC, gene-orf02976), diaminobutyrate transaminase (DoeD, gene-orf01883), and EctD (ectD gene-orf01882) are closely associated enzymes; and DoeA and EctD play particularly important roles [25]. In addition, mechanosensitive channels to osmoadaptation (e.g., osmoregulated transporter TeaABC) can also determine the ectoine excretion and accumulation [26]. In line with this, the expression of gene-orf01883, gene-orf02976, and gene-orf01882 were up-regulated with at least 1.8-fold change by NaCl treatment (Table S3), and the protein levels of orf01883 were also upregulated by 2.2-fold change, which confirmed that NaCl has promotive effects on ectoine production.

Transporters enable the uptake of ectoine when these nitrogen-rich compounds such as L-glutamate are exploited as nutrients [27–29]. In our enrichment analysis of GO terms, many pathways related to phosphate transport, phosphate ion transmembrane transport, phosphate ion transport, and ATPase-coupled anion transmembrane transport were significantly enriched in the list of both DEGs and DAPs in the comparison of UV2-NaCl vs. UV2 (Fig. 5 and Fig. S4). In transcriptomic and proteomic combined analysis on the list of overlapped DEGs between UV2-NaCl vs. UV2, we also found that pathways of ion transmembrane transporter activity, active and anion transmembrane transporter activity were significantly enriched.

The ABC module is known to bind and hydrolyze ATP, the primary sequence is highly conserved, displaying a typical phosphate-binding loop, therefore making contact with the gamma phosphate of the ATP molecule [28]. It was well known that some ABC transporters could be involved in either ectoine biosynthetic process or pre-formed ectoine import. For example, an Ehu-type binding-protein-dependent ABC phosphate transporter was involved in pre-formed ectoine import in P. lautus [28, 30, 31]. Notably, the relationship between phosphate transporters and ectoine biosynthesis was much less reported. Our study suggested that these transports could be required for the two mutant strains with promoted ectoine production. Overall, we observed that phosphate supply could enhance ectoine production and the expression of the five DEGs related to functional ABC phosphate transporters and ABC transporters related-regulatory enzymes was either slightly or dramatically inhibited under phosphate-sufficient conditions. Similar results were also observed in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 [32]. Lee’s work reported that the relative expression of some ABC phosphate transporter genes was highly stimulated in Pi-depleted conditions. In contrast, the expression levels of ABC phosphate transporters could be decreased under Pi-sufficient conditions as observed in our study. We hence inferred that the five promising DEGs related to functional ABC phosphate transporters and ABC transporters related-regulatory enzymes might play critical roles in regulating ectoine production through alterations in phosphate supply. However, the precise mechanism by which these five phosphate ABC transporters regulated ectoine production remained unknown. This aspect could be an interesting area for future research.

Consistent with the critical role of the ABC phosphate transporter in ectoine production in the two UV-induced mutant strains, we found that 3 out of the 5 common DEGs were annotated as phosphate-binding protein (orf01280), phosphate ABC transporter permease PstA (orf01282) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (orf01284) (Fig. 5A). Orf01282 was the most valuable target because the expression pattern of orf01282 was remarkably reduced in both UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatment groups, including UV0-NaCl, UV1-NaCl, and UV2-NaCl, relative to UV0 as shown in transcriptomic analysis (Fig. 5A) and validated by qPCR (Fig. 5C). It was worth mentioning that, together with orf01280 and orf01284, orf01282 was located at the core node in the PPI network (Fig. S9). Interestingly, this gene has been largely unknown in the fields of either Halomonas or ectoine production so far.

Notably, gene expression levels observed in the transcriptomic analysis did not fully correlate with the protein levels from the proteomic analysis. For instance, the expression of orf01280 declined, while its protein levels increased in UV0-NaCl compared to UV0. This discrepancy could be attributed to severval factors: (1) increased mRNA stability through mechanisms such as lengthening the poly-A tail [33] or reducing mRNA degradation to extend its half-life; (2) post-translational modification, such as reduced ubiquitination, which may extend protein half-life [34]; (3) enhanced translation efficiency [35].

In addition, there was a strong relationship between the primary metabolic pathway and the secondary metabolic pathway [36]. In the five common genes, we found that orf01284 is annotated as a G3PDH dehydrogenase, catalyzing G3P to OAA. During this process, it can also produce N-γ-acetyl-l-2,4-diaminobutyrate catalyzed by L-diaminobutyrate acetyltransferase (EctA), in another branch, which was a precursor substrate of ectoine [37], thereby G3PDH was very likely to promote the ectoine production. Consistent with this, we found that the orf01284 was strongly upregulated in protein levels, and it was in the same module of the PPI network. In addition, the expression of EctA (gene-orf01884) gene was significantly increased by UV0-NaCl relative to UV0 (Table S3). Interestingly, there was no significant alteration in the other two comparisons or protein levels across three comparisons of UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments.

Conclusions

In this study, we observed that ectoine production was increased in the XH26 strain with NaCl treatment, and two mutant strains with UV mutagenesis. Many pathways, including phosphate transport, phosphate ion transmembrane transport, phosphate ion transport, and ATPase-coupled anion transmembrane transport, were significantly enriched in the list of both DEGs and DAPs in the comparison of UV2-NaCl vs. UV2, and based on combined analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data. Additionally, we identified five common DEGs, including orf01280, orf01282, orf00986, orf01283, and orf01284, that exhibited negatively-correlation in both mRNA and protein levels with ectoine production under UV mutagenesis and NaCl treatments. This study highlighted the importance of gene editing the five common genes in the improvement of ectoine production, which provided a promising strategy for improving ectoine fermentation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We specially thank Dr. Yaozong Wu (Honest Biotech. Co., Ltd., ShangHai, China) and Zhongkang Omics Biotech Company for their contributions to the technical guidance and support concerning the LC-MS/MS analysis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Guoping Shen, Yanbing Lin; Methodology: Lijuan Qiao, Guoping Shen, Rui Han, Rong Wang; Investigation: Lijuan Qiao, Guoping Shen, Rui Han, Rong Wang, Xiang Gao, Jiangwa Xing; Writing: Derui Zhu, Yanbing Lin; Funding Acquisition: Derui Zhu; Resources: Derui Zhu; Supervision: Derui Zhu, Yanbing Lin.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation Project of China (32260019) and Applied Basic Research Program of Qinghai Province (2022-ZJ-771).

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomic data have been deposited to the Integrated Proteome Resources (https://www.iprox.cn) with the dataset identifier PXD057477.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yanbing Lin, Email: linyb2004@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Derui Zhu, Email: zhuderui2005@126.com.

References

- 1.Corral P, Amoozegar MA, Ventosa A. Halophiles and their biomolecules: recent advances and future applications in biomedicine. Mar Drugs. 2019;18(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Z, Li Y, Gao X, Xing J, Wang R, Zhu D, Shen G. Comparative genomic analysis of Halomonas campaniensis wild-type and ultraviolet radiation-mutated strains reveal genomic differences associated with increased ectoine production. Int Microb. 2023;26(4):1009–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu M, Liu H, Shi M, Jiang M, Li L, Zheng Y. Microbial production of ectoine and hydroxyectoine as high-value chemicals. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong Y, Zhang H, Wang X, Ma J, Lei P, Xu H, Li S. Enhancing ectoine production by recombinant Escherichia coli through step-wise fermentation optimization strategy based on kinetic analysis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2021;44:1557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao Z, Deng W, Li S, He J, Ren S, Huang W, Lu Y, Zhao G, Cai Z, Wang J. GlnR-mediated regulation of ectABCD transcription expands the role of the GlnR regulon to osmotic stress management. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(19):3041–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker J, Schäfer R, Kohlstedt M, Harder BJ, Borchert NS, Stöveken N, Bremer E, Wittmann C. Systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of the chemical chaperone ectoine. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivaramakrishnan R, Incharoensakdi A. Enhancement of lipid production in Scenedesmus sp. by UV mutagenesis and hydrogen peroxide treatment. Bioresour Technol. 2017;235:366–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Essemine J, Shang C, Zhang H, Zhu X, Yu J, Chen G, Qu M, Sun D. Combined proteomics and metabolism analysis unravels prominent roles of antioxidant system in the prevention of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) against salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;30;21(3):909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Jiang C, Bi Y, Mo J, Zhang R, Qu M, Feng S, Essemine J. Proteome and transcriptome reveal the involvement of heat shock proteins and antioxidant system in thermotolerance of Clematis florida. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wingett SW, Andrews S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Res. 2018, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lohse M, Bolger AM, Nagel A, Fernie AR, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Usadel B. R obi NA: a user-friendly, integrated software solution for RNA-Seq-based transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(W1):W622–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Essemine J, Bunce JA, Shang C, Zhang H, Sun D, Chen G, Qu M. Roles of heat shock protein and reprogramming of photosynthetic carbon metabolism in thermotolerance under elevated CO2 in maize. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;168(1):103869.

- 13.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of Fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang W, Zhou Y, Wang L, You X, Zhang Y, Cheng C-L, Chen W. Ultrastructural, physiological and proteomic analysis of Nostoc flagelliforme in response to dehydration and rehydration. J Proteom. 2012;75(18):5604–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1–2):248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaccai G, Bagyan I, Combet J, Cuello GJ, Demé B, Fichou Y, Gallat F-X, Galvan Josa VM, Von Gronau S, Haertlein M. Neutrons describe ectoine effects on water H-bonding and hydration around a soluble protein and a cell membrane. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):31434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn MB, Smales GJ, Seitz H, Solomun T, Sturm H. Ectoine interaction with DNA: influence on ultraviolet radiation damage. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2020;22(13):6984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittmar J, Meyer S, Sieling T, Kunte J Jr, Brand I. What does ectoine do to DNA? A molecular-scale picture of compatible solute–biopolymer interactions. J Phys Chem B. 2020;124(37):7999–8011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W-C, Hsu C-C, Lan JC-W, Chang Y-K, Wang L-F, Wei Y-H. Production and characterization of ectoine using a moderately halophilic strain Halomonas salina BCRC17875. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;125(5):578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L-S, Ma C-R, Ji Q, Wang Y-F. Genome-wide identification, classification and expression analyses of SET domain gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Yi Chuan Hered. 2009;31(2):186–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhao Q, Li S, Lv P, Sun S, Ma C, Xu P, Su H, Yang C. High ectoine production by an engineered Halomonas hydrothermalis Y2 in a reduced salinity medium. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudek L, Premachandra D, Webster W, Bräu L. Role of phosphate transport system component PstB1 in phosphate internalization by Nostoc punctiforme. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(21):6344–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemieux MJ, Huang Y, Wang D-N. Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter of Escherichia coli: structure, function and regulation. Res Microbiol. 2004;155(8):623–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reshetnikov AS, Rozova ON, Trotsenko YA, But SY, Khmelenina VN, Mustakhimov II. Ectoine degradation pathway in halotolerant methylotrophs. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0232244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandrich J, Pfeiffer F, Alfaro-Espinoza G, Kunte HJ. Contribution of mechanosensitive channels to osmoadaptation and ectoine excretion in Halomonas elongata. Extremophiles. 2020;24:421–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwibbert K, Marin-Sanguino A, Bagyan I, Heidrich G, Lentzen G, Seitz H, Rampp M, Schuster SC, Klenk HP, Pfeiffer F. A blueprint of ectoine metabolism from the genome of the industrial producer Halomonas elongata DSM 2581T. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13(8):1973–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richter AA, Mais C-N, Czech L, Geyer K, Hoeppner A, Smits SH, Erb TJ, Bange G, Bremer E. Biosynthesis of the stress-protectant and chemical chaperon ectoine: biochemistry of the transaminase EctB. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz A, Stöveken N, Binzen IM, Hoffmann T, Heider J, Bremer E. Feeding on compatible solutes: a substrate-induced pathway for uptake and catabolism of ectoines and its genetic control by EnuR. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(3):926–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanekop N, Höing M, Sohn-Bösser L, Jebbar M, Schmitt L, Bremer E. Crystal structure of the ligand-binding protein EhuB from Sinorhizobium meliloti reveals substrate recognition of the compatible solutes ectoine and hydroxyectoine. J Mol Biol. 2007;374(5):1237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jebbar M, Sohn-Bösser L, Bremer E, Bernard T, Blanco C. Ectoine-induced proteins in Sinorhizobium meliloti include an ectoine ABC-type transporter involved in osmoprotection and ectoine catabolism. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(4):1293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J, Iwata Y, Suzuki Y, Suzuki I. Rapid phosphate uptake via an ABC transporter induced by sulfate deficiency in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Algal Res. 2021;60:102530. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passmore LA, Coller J. Roles of mRNA poly (A) tails in regulation of eukaryotic gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(2):93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tai H-C, Schuman EM. Ubiquitin, the proteasome and protein degradation in neuronal function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(11):826–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verma M, Choi J, Cottrell KA, Lavagnino Z, Thomas EN, Pavlovic-Djuranovic S, Szczesny P, Piston DW, Zaher HS, Puglisi JD. A short translational ramp determines the efficiency of protein synthesis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mo R, Han G, Zhu Z, Essemine J, Dong Z, Li Y, Deng W, Qu M, Zhang C, Yu C. The ethylene response factor ERF5 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in ‘Zijin’ mulberry fruits by interacting with MYBA and F3H genes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Pastor JM, Bernal V, Salvador M, Argandoña M, Vargas C, Csonka L, Sevilla Á, Iborra JL, Nieto JJ, Cánovas M. Role of central metabolism in the osmoadaptation of the halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter salexigens. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17769–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomic data have been deposited to the Integrated Proteome Resources (https://www.iprox.cn) with the dataset identifier PXD057477.