Abstract

Background

The increasing number of young adults seeking cheaper and easily accessible orthodontic treatment from unlicensed practitioners in Malaysia poses significant risks to patients. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate their motivations and awareness regarding such practices. The objective of our study was to assess the knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of non-dentists offering orthodontic treatment among the Malaysian young adult population.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study. An online self-administered questionnaire was distributed to Malaysian citizens aged 18–37 years. The questionnaire consisted of 11 questions that investigated their awareness of non-dentists offering orthodontic treatment, the harmful effects of braces fitted by non-dentists, and potential strategies to mitigate this phenomenon.

Results

The study was completed by 426 participants, predominantly Malay, with a mean age of 22.9 years. A total of 76.1% reported awareness of braces fixed by non-dentists, primarily through social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook. Lower cost emerged as the predominant motive (83.6%) for opting for non-dentist orthodontic treatment, followed by no waiting list (48.8%). Notably, the majority of participants acknowledged the illegality (70%) and potential harm (77%) associated with non-dentists providing orthodontic treatment. Legal enforcement (53.1%) was identified as the preferred method for mitigating this practice. Occupation significantly influenced knowledge of illegal orthodontic treatment (p < 0.05), however no significant association was found for gender and level of education (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

The survey revealed that young adults are aware of and informed about non-dentists offering orthodontic treatment. While they identified cost as the primary reason for seeking such services, they also recognized legislation and public awareness through campaigns and social media as effective strategies to address this issue. Additionally, significant differences in legal awareness were observed among different occupational levels.

Keywords: Non-dentist, Young adults, Knowledge, Influence, Perception

Introduction

The global rise in demand for orthodontic treatment has been accompanied by a concerning increase in orthodontic treatment provided by non-dentists. Non-dentists refer to unqualified practitioners or individuals lacking proper dental credentials and regulatory approval who provides dental treatment. These illegal practices are often termed “fashion braces” or “fake braces” depending on the region [1–3].

This issue is particularly prevalent in Malaysia [4, 5], where societal pressures and social media trends influence young adults to seek these risky alternatives [6]. Orthodontic procedures performed by non-dentists, often marketed as affordable and convenient, pose significant health risks and underscore critical barriers within the healthcare system that drive individuals toward unsafe practices [4]. Patients may also experience damage to their teeth and oral mucosa, and a lack of adherence to safety and hygiene standards can result in the transmission of disease. Furthermore, treatments provided by non-dentists’ individuals are not regulated, making patients ineligible to claim any damages or compensation resulting from these practices.

Globally, orthodontic treatment provided by non-dentist reflects systemic barriers in healthcare access, awareness, and treatment costs [7–9]. In Thailand, these illegal practices have been a concern since 2006, with a reported death linked to this unsafe practice [10]. In India, dental procedures provided by non-dentists are referred to as quackery. It is widespread, and has extended beyond orthodontics to various specialties mainly prosthodontics, indicating broader issues of inadequate access and high treatment costs [11, 12].

This problem is not confined to middle- and low-income countries. In the United States, there are increasing reports on the use of fake orthodontic brackets and wires that resemble real braces but are non-functional in aligning teeth [13]. This phenomenon, known as “basement braces,” is the latest addition to rising online trends and highlights the widespread unawareness of the dangers of these practices. In Malaysia, the issue was further exposed when a non-dentist practitioner reported herself to the authorities because some of her customers did not pay for her services, revealing a lack of understanding not only among patients but also among the practitioners themselves [14].

Cost barriers play a significant role in the prevalence of non-dentists providing orthodontic procedures [1]. In many countries, the high cost of licensed orthodontic treatment is attributed to the initial cost of setting up the dental clinic and the operational costs of running a licensed dental clinic. These include purchasing of dental materials, instruments, salary, rental, utility bills and others. The need for licensed facilities that adhere to stringent safety and regulatory standards also contributes to costly orthodontic treatment. Meanwhile, the non-dentists carry out their procedure at home, in hotel rooms and beauty salons reduces the cost of orthodontic treatment but poor infection control will expose patient to infections such as Hepatitis B, C and HIV [5].

In Malaysia, the public sector provides orthodontic treatment at a significantly reduced cost due to subsidies provided by the government. However, due to limited resources, the waiting time to receive the treatment is about 2–3 years and is only available to patients aged 18 or younger with an Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need score (IOTN) of 4 and 5 [15]. Consequently, patients older than 18 and or with an IOTN score of 1 to 3 have no other option but to seek treatment in the private sector. Private orthodontic care is not covered by health insurance and costs are significantly higher. This makes the cheaper and readily available services offered by non-dentists more enticing to patients.

The rise of dental treatments by non-dentists can also be attributed to the parallel increase in online marketplaces or e-commerce paltforms [16]. Traditionally, orthodontic products were sold by registered dental suppliers who ensured that purchasers were registered dentists. Online marketplaces bypass these checks, lacking safety standards and facilitating the proliferation of dental procedures provided by non-dentist. Regulatory barriers in controlling the sale of dental products on these platforms contribute significantly to the rise of this practice. It is challenging for regulators to monitor these sales due to the numerous online marketplaces available and the ability of sellers to mask items with different names or reopen accounts after being banned.

A significant barrier to addressing the rise of non-dentists offering orthodontic treatment is the challenge of raising awareness among young adults [1, 3]. Traditional methods of public health education often rely on print media, public service announcements, and educational campaigns conducted in colleges, universities, and community settings. These methods focused on broad information dissemination through controlled, reliable sources and were typically designed to reach a general audience [17].

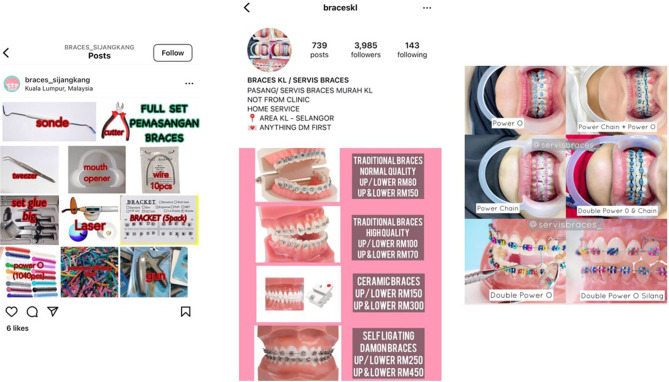

In contrast, current methods of information dissemination are dominated by digital platforms [18]. Influencers, podcasts, and social media such as Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok now play a central role in shaping perceptions and spreading information [4, 19]. These platforms offer rapid and widespread reach which enables the non-dentist to advertise their illegal dental services (Fig. 1). However, this contributes to the proliferation of unverified and misleading content. Young adults, who are the primary users of these platforms, are exposed to persuasive marketing and endorsements that may obscure the true risks associated with orthodontic treatment provided by non-dentist. This shift from traditional to digital media has created gaps in effective communication and education, as traditional public health campaigns may not adequately address the unique information-seeking behaviors and understanding of this demographic [20].

Fig. 1.

Example of social media post advertising orthodontic treatment by a non-dentist

The dramatic increase in reported cases of non-licensed orthodontic treatments in Malaysia, particularly among young adults from secondary schools in Kuala Lumpur, underscores the urgent need to address these barriers [21]. Reports indicate a significant rise in cases linked to this demographic, emphasizing the need for targeted public health interventions and regulatory reforms. Additional barriers to healthcare, such as high costs, limited access and long waiting time, create a challenging environment where young adults may turn to unsafe, non-licensed alternatives in their quest for affordable and fast cosmetic procedures.

This study aims to explore how these barriers to healthcare contribute to the rise in non-dentist orthodontic procedures. By examining the knowledge and awareness of young adults regarding these illegal treatments, the research seeks to identify gaps in understanding and misinformation. Insights from this study will inform public health strategies and policy developments, focusing on improving access to safe, licensed orthodontic treatment and addressing systemic barriers.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants characteristic

This study used a cross-sectional online survey and obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Research Board. The study was designed, conducted, and reported following best practice guidelines and in accordance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys [22]. Participants were selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure a relevant and representative sample. The inclusion criteria required participants to be young adults aged 18–37 years, Malaysian citizens, and proficient in either Malay or English. Additionally, participants needed access to the internet to complete the online survey. The exclusion criteria included individuals outside the age range of 18–37 years and those who did not provide informed consent.

Sample size calculation

An appropriate sample size was calculated using the software Raosoft (Raosoft, Inc., USA) with a confidence interval of 95%, a margin of error of 5% and an estimated population size of 11,000. This indicated that a minimum of 385 participants were required for this study; however, the sample size was increased to 424 to account for a potential dropout rate of 10%.

Development and validation of the questionnaire

An online survey, available in both Malay and English, was developed for this study to ascertain several key aspects: patient demographics and education levels, awareness of non-dentists and fake braces, the harmful effects of braces fitted by non-dentists, and potential strategies to mitigate this phenomenon. The questionnaire construction process involved a comprehensive review of previous studies and literature, examining socio-economic and educational factors influencing individuals seeking orthodontic treatment from non-dentists, as well as the common effects of such practices. Additionally, the current legal framework was analyzed, particularly focusing on the Malaysian Dental Act 1971 and 2018 and relevant healthcare guidelines, to provide a comprehensive context.

To ensure content validity, an expert orthodontist and a language professional reviewed the item selection and language usage. This review was crucial in confirming that the questions accurately reflected the study’s objectives and were phrased clearly for the target population. The questionnaire was then pilot tested on a small sample of five individuals to identify any issues related to clarity, comprehension, reliability, and readability. Feedback from this pilot test was used to make necessary adjustments.

Given the bilingual nature of the survey, careful attention was paid to the translation process to maintain semantic equivalence in both languages. This involved not just direct translation but also cultural adaptation to ensure contextual relevance and comprehensibility. Ongoing validation was conducted throughout the data collection process, addressing any ambiguities or issues reported by respondents.

The final version of the questionnaire, consisting of 11 questions, is divided into three main components. Firstly, the demographic section collects information such as patient age, race, gender, occupation, and education level. Secondly, the section on patient knowledge and awareness focuses on participants’ understanding of the differences between non-dentists, dentists, and orthodontists, whether they have heard of non-dentists, and their awareness of the effects of treatment by unqualified practitioners. Lastly, the perception component gathers participants’ opinions on why individuals may seek orthodontic treatment from non-dentists, methods to enhance public awareness of this issue, and potential strategies to address it.

Data collection

A snowball sampling strategy was utilized for this study. The questionnaire was initially imported into Google Forms and distributed among the students at the research team’s institution. These students were then encouraged to share the questionnaire with others. During the initial distribution within the institution, participants were asked to provide feedback on clarity, which helped to further validate the questionnaire.

Following this pre-distribution phase, the link to the Google Forms was distributed to the target demographic via social media platforms, including WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram. The survey was available for a 7-month period. Participants were provided with an information sheet explaining the purpose of the study, and written consent was obtained prior to answering the questions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, USA). Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize the data, with results reported as means and percentages, providing a clear overview of the demographic characteristics of the sample and the prevalence of key variables of interest. Qualitative comments from the questionnaire were analyzed to identify trends and categorized into themes. Key phrases and sentences were highlighted to capture the main points. Similar codes were grouped into broader themes that represented significant trends. Each theme was named to reflect its core message and supported by direct quotes from participants. Additional Statistical analysis was conducted to examine the differences in responses to key questions based on demographic factors, including gender, level of education, and occupation. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were employed to determine the significance of the associations between these demographic variables and the participants’ responses. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 426 participants were recruited for this study. The mean age of the participants was 22.9 ± 3.5 years. The majority were of Malay ethnicity (n = 385, 90.4%) and students (n = 300, 70.4%), with 320 participants (75.1%) having attained a diploma or bachelor’s degree (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic of the participants

| Category | Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 106 (24.9) |

| Female | 320 (75.1) | |

| Ethnicity | Malay | 385 (90.4) |

| Chinese | 23 (5.4) | |

| Others | 18 (4.2) | |

| Occupation | Student | 300 (70.4) |

| Support staff | 28 (6.6) | |

| Management and professional | 65 (15.3) | |

| Self-employed | 33 (7.7) | |

| Level of education | Primary education (SPM/STPM) | 83 (19.5) |

| Secondary education (Dip/BD) | 320 (75.1) | |

| Tertiary education (Master/PHD) | 23 (5.4) |

Values are given as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

SPM, Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia; STPM, Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia; Dip, diploma; BD, bachelor’s degree

Approximately 60.8% of participants were unsure or did not know the difference between an orthodontist and a dentist (Table 2). However, if given the option of having braces fitted by a dentist or an orthodontist, 68.3% chose an orthodontist. Most participants (n = 364, 76.1%) had heard of braces being fitted by a non-dentist, with the majority hearing about it through social media platforms such as Instagram (n = 120, 37.1%) and Facebook (n = 155, 47.9%). A high proportion of participants were aware that it is against the law for non-dentists to fit dental braces (n = 298, 70%), that treatment by a non-dentist does not provide the same result as that achieved by a qualified dentist or orthodontist (n = 282, 66.2%), and that it is harmful to the wearer (n = 328, 77%).

Table 2.

Participant knowledge and awareness

| Questions | Answer | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. Do you know the difference between a Dentist and an Orthodontist? | Yes | 168 (39.4) |

| No | 138 (32.4) | |

| Not sure | 120 (28.2) | |

| Q2. If you want to have braces or orthodontic treatment, who would you choose? | Dentist | 135 (31.7) |

| Orthodontist | 291 (68.3) | |

| Q3. Have you heard about braces which are fixed (put on) by a non-dentist? | Yes | 324 (76.1) |

| No | 77 (18.1) | |

| Not sure | 25 (5.9) | |

| Q4. Where did you hear about it? | News | 76 (23.5) |

| Newspaper | 86 (26.5) | |

| 155 (47.9) | ||

| 120 (37.1) | ||

| Friends | 89.1 (27.5) | |

| Family | 32 (9.90) | |

| Q5. Does the activity of fixing (putting on) dental braces by non-dentist is against the law? | Yes | 298 (70.0) |

| No | 14 (14.0) | |

| Not sure | 114 (26.8) | |

| Q6. Do braces (orthodontic treatment) provided by a non-dentist produce the same results as braces (orthodontic treatment) provided by a Dentist or Orthodontist? | Yes | 29 (6.8) |

| No | 282 (66.2) | |

| Not sure | 115 (27.0) | |

| Q7. Do braces that are fixed (put on) by a non-dentist can be harmful to the wearer? | Yes | 328 (77.0) |

| No | 13 (3.10) | |

| Not sure | 85 (20.0) | |

| Q8. What are the harmful effects of braces fixed (put on) by a non-dentist? | Gum disease | 298 (70.0) |

| Tooth decay | 132 (31.0) | |

| Tooth mobility | 285 (66.9) | |

| Mouth ulcer | 146 (34.3) | |

| Non-vital tooth | 171 (40.1) |

The top reason given by participants for accepting braces or orthodontic treatment from a non-dentist was lower cost (n = 356, 83.6%), followed by no waiting list (n = 208, 48.8%), easy availability (n = 193, 45.3%), being hassle-free (n = 173, 40.6%), following the latest fashion trend (n = 170, 39.9%), being trendy (n = 163, 38.3%), no follow-up needed (n = 160, 37.6%), and social status (n = 107, 25.1%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant perceptions

| Questions | Answer | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Q9. Reasons for receiving braces (orthodontic treatment) from a non-dentist |

Cheaper cost | 356 (83.6) |

| No waiting list | 208 (48.8) | |

| Hassle free (no X-ray, study model required) | 173 (40.6) | |

| Trendy | 163 (38.3) | |

| Latest fashion trend | 170 (39.9) | |

| Easily available | 193 (45.3) | |

| Do not require follow-up treatment | 160 (37.6) | |

| Appear to be in higher social status | 107 (25.1) | |

| Q10. How do we increase public awareness about the harmful effect of getting braces fixed (put on) by a non-dentist? | Awareness campaign | 208 (48.8) |

| Talks | 12 (2.8) | |

| Mass media | 164 (38.5) | |

| Law | 7 (1.6) | |

| Reduce cost of dental treatments | 12 (2.8) | |

| Dental education | 14 (3.3) | |

| Others | 9 (2.1) | |

| Q11. In your opinion, how can you help to curb the illegal practice of a non-dentist fixing braces? | Laws | 226 (53.1) |

| Report to higher authorities | 29 (6.8) | |

| Mass media | 21 (4.9) | |

| Reduce dental cost | 14 (3.3) | |

| Operation by higher authorities | 47 (11.0) | |

| Awareness campaign | 53 (12.4) | |

| Others | 36 (8.5) |

The two most effective ways perceived by participants to increase public awareness on the potential harmful effects of braces fitted by a non-dentist were by conducting awareness campaigns (n = 208, 48.8%) and using mass media (n = 164, 38.5%). Table 3 shows the range of opinions on how to curb the illegal practice of non-dentists, with legal enforcement (n = 226, 53.1%) considered the most preferable method.

No association was found in gender and level of education regarding knowledge and perceptions of illegal orthodontic treatment provided by non-dentists (p > 0.05) (Tables 4 and 5). Occupation significantly influenced knowledge that braces fixed by non-dentists are against the law (p < 0.05). However, it does not influence knowledge on differences between a dentist and an orthodontist as well as the harmful effect of braces provided by non-dentist (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 4.

Association of knowledge and perceptions by gender

| Question | Gender | Yes | No | Not sure | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | |||

| Q1: Do you know the difference between a Dentist and an Orthodontist? | Male | 34 | 40 | 32 | p > 0.05 |

| Female | 134 | 98 | 88 | ||

| Q5: Does the activity of fixing (putting on) dental braces by non-dentist is against the law? | Male | 67 | 4 | 35 | p > 0.05 |

| Female | 231 | 10 | 79 | ||

| Q8: Do braces that are fixed (put on) by a non-dentist can be harmful to the wearer? | Male | 76 | 4 | 26 | p > 0.05 |

| Female | 252 | 9 | 59 |

Chi-square test was applied to assess differences in responses between genders

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Table 5.

Association of knowledge and perceptions by level of education

| Question | Level of education | Yes | No | Not sure | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | |||

| Q1: Do you know the difference between a Dentist and an Orthodontist? | SPM/STPM/Matriculation | 40 | 25 | 18 | p > 0.05* |

| Diploma | 23 | 23 | 17 | ||

| Basic Degree | 92 | 84 | 81 | ||

| Master | 11 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Phd | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Q5: Does the activity of fixing (putting on) dental braces by non-dentist is against the law? | SPM/STPM/Matriculation | 55 | 2 | 26 | p > 0.05† |

| Diploma | 41 | 7 | 15 | ||

| Basic Degree | 183 | 5 | 69 | ||

| Master | 15 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Phd | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q8: Do braces that are fixed (put on) by a non-dentist can be harmful to the wearer? | SPM/STPM/Matriculation | 61 | 4 | 18 | p > 0.05† |

| Diploma | 46 | 5 | 12 | ||

| Basic Degree | 202 | 3 | 52 | ||

| Master | 15 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Phd | 4 | 0 | 0 |

†Fisher’s Exact Test

*Chi-Square Test

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

SPM, Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia; STPM, Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia; Dip, Diploma; BD, Bachelor’s Degree

Table 6.

Association of knowledge and perceptions by occupation

| Question | Occupation | Yes | No | Not sure | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Q1: Do you know the difference between a Dentist and an Orthodontist? | Student | 114 | 98 | 88 | p > 0.05* |

| Support staff | 11 | 12 | 5 | ||

| Management and professional | 26 | 19 | 20 | ||

| Self-employed | 17 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Q5: Does the activity of fixing (putting on) dental braces by non-dentist is against the law? | Student | 199 | 6 | 95 | p < 0.05† |

| Support staff | 25 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Management and professional | 51 | 4 | 10 | ||

| Self-employed | 23 | 3 | 7 | ||

| Q8: Do braces that are fixed (put on) by a non-dentist can be harmful to the wearer? | Student | 223 | 10 | 67 | p > 0.05† |

| Support staff | 27 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Management and professional | 53 | 3 | 9 | ||

| Self-employed | 25 | 0 | 8 |

†Fisher’s Exact Test

*Chi-Square Test

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Discussion

The findings of our study underscore the significant role that cost considerations and limited awareness play among young adults when it comes to non-dentist orthodontic procedures. Approximately 83.6% of participants identified lower costs as a critical factor in their decision to acquire orthodontic treatment from non-dentist. A study in four secondary schools in Malaysia revealed that 72.4% of adolescents aged 17 and below cited cost savings as the primary reason for opting for fake braces [23]. These findings highlight the persistent issue of cost as a driving factor for seeking orthodontic treatment from non-dentists.

Participants sought orthodontic treatment from non-dentists for other reasons such as no waiting list (48.8%), easy availability (45.3%), hassle-free procedures (40.6%), following fashion trends (39.9%), and requiring no follow-up (37.6%). In contrast, a study by Parlani et al. in India found that the primary reason for seeking dental treatment from non-dentists was a lack of awareness (50%), followed by cost (26%)[12]. Information about such practices mainly came from friends and family (59%), with the media contributing less (22.7%).

Currently, social media emerges as a pivotal platform in shaping perceptions, where its influence extends to both spreading misinformation and serving as a tool for awareness. Our study revealed that among participants 18–37 years of age, social media platforms such as Facebook (47.9%) and Instagram (37.1%) were the predominant source of information or advertisement on non-dentists providing orthodontic treatment. In comparison, participants aged 17 and below reported even higher percentages, with 62% receiving information via Instagram and 58% through Facebook. Nevertheless, 26.5% of participants aged 18–37 and 35% of those aged 17 and below cited newspapers as their source of information. This shows that traditional media still holds considerable influence among younger adolescents [23].

Apart from social media, 27.5% of our participants acquired information on non-dentists providing orthodontic treatment from peers or friends. Another study also revealed that among those aged 17 and below, 69% cited peers, highlighting the strong influence of social circles, especially among younger adolescents [23]. Family was the least reported source overall, with only 9.9% of participants aged 18–37 mentioning family. However, among participants aged 17 and below, 49.7% reported family as a source, indicating that younger adolescents may still rely more on family for information compared to older age groups.

When it comes to awareness on the illegality of non-dentist providing orthodontic treatment, differences were observed across age groups. A high proportion of participants aged 18–37 (70%) knew that it was against the law for non-dentists to fit braces. However, among participants aged 18–20, 31% mistakenly believed that services provided at facilities other than dental clinics are lawful [24]. In addition, only 35% of those aged 17 and below were aware that non-dentists providing orthodontic treatment can be sentenced to court [23]. In addition, our study revealed a significant association between occupation with their knowledge on illegality of non-dentists providing braces. These findings highlight the need for targeted educational campaigns to enhance awareness about the illegality and risks of non-dentist providing orthodontic services.

A significant proportion of participants in our study (66.2%) were unaware that treatment by a non-dentist practitioner does not yield the same results as treatment by a qualified dentist or orthodontist. This finding aligns with the study by Kamarozaman et al. [24], which reported that 42.5% of participants believed the quality of teeth alignment is the same whether dental braces are applied at a dental clinic or elsewhere. Both studies underscore the urgent need to bridge this knowledge and awareness gap and emphasize the long-term risks associated with unqualified providers.

A high proportion of participants (77%) were aware of the potential harm caused by non-dentist orthodontic treatments. However, despite understanding the associated risks, many individuals still seek treatment from non-dentists. This behavior is likely driven by barriers to accessing quality care, such as high costs and limited availability, making non-dentist services the only viable option for some individuals. These individuals may hope or assume that the risks are minimal, influenced by misleading advertisements from non-dentist providers [19].

This barrier indirectly affects the public sector. As harm from these treatments impacts the teeth and gums, patients initially seeking low-cost alternatives may ultimately require treatment from the public sector to address complications. For conditions like dental caries and gingivitis, there is no age limit, and the cost of treatment is heavily subsidized by the government. Consequently, the government will indirectly bear the cost of these unlawful acts, further straining the healthcare system.

Most participants were aware that practicing fake dentistry is against the law and believed that legislation is one of the ways to curb this illegal practice. According to the Malaysian Dental Act, the practice of dentistry by an unqualified individual or in an illegal location is prohibited, and violators can be prosecuted in court [25]. To enforce the law effectively, authorities require public cooperation to report illegal practices and catch non-dentist practitioners in the act [26]. The public should be made aware not only of the potential harm of non-licensed dentistry but also of ways to report it. According to study participants, awareness campaigns and using mass media are the most effective ways to increase public awareness of fake dental practices. However, mass media should not be limited to news portals; greater emphasis should be placed on social media [27].

To effectively increase awareness and counteract the widespread misinformation online, there is a critical need for studies that compare the trustworthiness and influence of social media influencers versus healthcare professionals [28]. Misinformation disseminated through social platforms can significantly erode young adults’ trust in professional healthcare advice. By conducting research that measures the credibility perceived by young adults in information provided by influencers compared to qualified professionals, we can better understand the dynamics influencing patient decisions. This understanding is crucial for designing awareness campaigns that effectively rebuild trust in professional medical advice and educate the public about the risks associated with unverified sources.

The provision of braces in Malaysia can be done by either a qualified dentist or an orthodontist. The majority of participants in this study were unsure of the difference between a dentist and an orthodontist, likely because both can offer orthodontic treatment. Approximately 30% of participants preferred treatment by a dentist, highlighting the personal nature of dental services. Patients often choose a dentist they are familiar and comfortable with over an orthodontist [29].

Although the number of licensed orthodontists in Malaysia is increasing, it remains significantly lower compared to countries like the United States [24]. Efforts to increase the number of licensed practitioners may not effectively reduce procedural costs due to the depreciating Malaysian Ringgit against the US Dollar [30], which inflates the cost of materials and limits the potential for reduced costs. This financial barrier drives individuals toward non-licensed options, which are perceived as more affordable despite their substantial risks.

To reduce the cost barrier, it is essential to address the high expenses associated with dental materials, which are predominantly manufactured in high-cost regions like the United States and Europe. These significant expenses are often passed onto consumers, making dental treatments prohibitively expensive, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Dental manufacturers could benefit from adopting strategies similar to those used in the automotive industry [31], such as relocating parts of the manufacturing process to countries with lower operational costs. This practice could help maintain high standards of quality while significantly reducing costs, thereby decreasing retail prices and making dental treatments more accessible.

A new alarming trend is the rise of direct-to-consumer (DTC) orthodontic aligners, representing an emerging concern in high- and middle-income countries that is likely to spread to low-income countries [32]. These aligners are marketed and sold directly to consumers without the traditional intermediation of healthcare professionals [33]. Driven by digital healthcare transformation and consumer demand for convenient, cost-effective aesthetic solutions, DTC aligner services typically involve online platforms offering aligner kits for home use. These services often bypass standard regulatory checks and medical oversight, posing significant risks in terms of safety and treatment efficacy [34, 35].

The authors believe that if these trends are allowed to spread, they could become even more difficult to tackle than conventional non-dentist orthodontic treatments. Suppliers or providers can be located anywhere in the world, making it challenging to enforce regulations across different nations when providers and patients are not in the same jurisdiction. Furthermore, since these practices are conducted online, monitoring and prevention become even harder. The global nature of the internet allows providers to operate from locations with lax regulations, targeting patients in countries with stricter laws. This transnational aspect complicates efforts to control the spread of illegal orthodontic treatments. Additionally, the anonymity and ease of online transactions enable these providers to evade detection and continue their operations despite local enforcement efforts.

Limitation

While this study provides insightful data, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, including a limited demographic scope and potential biases inherent in self-reported data. The use of a snowball sampling strategy introduces several potential biases. One significant bias is selection bias, as the initial participants from the research team’s institution may share similar characteristics, leading to a lack of diversity in the sample. Additionally, there is a risk of non-response bias, where individuals who choose to participate may have different perspectives or characteristics compared to those who do not respond, potentially skewing the results.

While this method allows for the recruitment of a larger number of participants, it may not accurately reflect the broader population. The reliance on social networks for distribution means that the sample may be over-representative of certain groups (e.g., those more active on social media) and under-representative of others (e.g., those without social media access or less internet-savvy individuals). However, since young adults often receive information through social media, where these non-dentist services are advertised, this may reduce the representativeness bias of the sample. Additionally, the method relies heavily on the willingness and ability of initial participants to recruit others, which can lead to an uneven and potentially biased sample.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that members of the young adult population do have an awareness and knowledge of non-dentist performing orthodontic treatment. They perceive cost as the major driving factor for seeking treatment. Significant differences in legal awareness were observed across occupations. Legislation and raising public awareness through campaigns and social media are seen to be ways to curb this problem.

Author contributions

A.I.S: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. E.R.P : Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. N.D.A.A: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. N.A.Y: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Supervision, Data Curation. K.A.M.K: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Supervision, Data Curation. M.M.N: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Supervision, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, of this article: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Univesiti Kebangsaan Malaysia ethical review board (reference no: UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2017-002). Each participant provided informed consent after receiving a comprehensive explanation regarding the nature, risks, and benefits of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alhazmi AS, Al Agili DE, Aldossary MS, et al. Factors associated with the use of fashion braces of the Saudi Arabian Youth: application of the Health Belief Model. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1). 10.1186/s12903-021-01609-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.New York Post. Fashion braces rising among young people as hot new accessory. New York Post.

- 3.Hakami Z, Chung HS, Moafa S, et al. Impact of fashion braces on oral health related quality of life: a web-based cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1). 10.1186/s12903-020-01224-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Mohd Nor NA, Wan Hassan WN, Mohamed Makhbul MZ, Mohd Yusof ZY. Fake braces by quacks in Malaysia: an Expert Opinion. Ann Dent Univ Malaya. 2020;27:33–40. 10.22452/adum.vol27no6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahab RMA, Hasan SK, Yamin NEM, Ibrahim Z. Awareness of fake braces usage among Y- generations. J Int Dent Med Res. 2019;12(2):663–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorooshian S, Kamarozaman AA. Fashion braces: an alarming trend. Sao Paulo Med J. 2018;136(5):497–8. 10.1590/1516-3180.2018.0296250718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain A. Dental quackery in India: an insight on malpractices and measures to tackle them. Br Dent J. 2019;226(4):257–9. 10.1038/s41415-019-0014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humagain M, Bhattarai BP, Rokaya D. Quackery in dental practice in Nepal. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2020;58(227):543–6. 10.31729/jnma.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Sun. M’sian quack dentist slapped with RM8k fine for performing procedures in Singapore. The Sun. Published 2024. https://thesun.my/style-life/going-viral/m-sian-quack-dentist-slapped-with-rm8k-fine-for-performing-procedures-in-singapore-OB12316668

- 10.Post B. Doctors warn fashionable dental braces can kill. Bangkok Post. Published online. 2018. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1393582/doctors-warn-fashionable-dental-braces-can-kill

- 11.Oberoi S, Oberoi A. Growing quackery in dentistry: an Indian perspective. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59(3):210. 10.4103/0019-557x.164661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parlani S, Tripathi S, Bhoyar A. A cross-sectional study to explore the reasons to visit a quack for prosthodontic solutions. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2018;18(3):231–8. 10.4103/jips.jips-24-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Association of Orthodontists. The rise of fashion braces: Why you should avoid this new trend. American Association of Orthodontists. Published 2024. https://aaoinfo.org/whats-trending/the-rise-of-fashion-braces-why-you-should-avoid-this-new-trend/

- 14.Murali RSN, Marhom S. Fake dentist gave herself away. The Star. Published. 2017. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/10/11/fake-dentist-gave-herself-away-womans-report-on-patients-who-failed-to-pay-tips-off-health-dept/

- 15.Zreaqat M, Hassan R, Ismail AR, Ismail NM, Aziz FA. Orthodontic treatment need and demand among 12- and 16 year-old school children in Malaysia. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2013;12(4):217–21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24390019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahrul Naing AI, Abd Rahman ANA. Orthodontic Prod Sold via Online Marketplaces Malaysia. 2021;1(Act 737):106–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edgerly S. Seeking out and avoiding the News Media: young adults’ proposed strategies for obtaining current events information. Mass Commun Soc. 2017;20(3):358–77. 10.1080/15205436.2016.1262424. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaabah QE, Agartha O, Awankwah PM. Sources of nutrition information and level of nutrition knowledge among young adults in the Accra metropolis. BMC Public Health Published Online 2018:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mohd Nor NA, Ab Aziz MH, Ramasindarum C, Kamarudin Y. Fake Braces’: a content analysis of Instagram Posts by Unlicensed Providers. J Heal Transl Med. 2023;26(1):135–42. 10.22452/jummec.vol26no1.19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim SC, Molenaar M, Annika B, Linda R, Mike. McCaffrey Tracy. Young adults’ use of Different Social Media Platforms for Health Information: insights from web-based conversations. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malaysia M. of H. Achieving zero number of fake braces usage among school children in SMK Seri Pantai. Published 2024. https://qaconvention.nih.gov.my/download/oral/OP 06 Achieving Zero Number of Fake Braces Usage Among School Children in SMK Seri Pantai.pdf.

- 22.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e132. 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayuni Ahmad Shaai N, Farhan Kamaruddin A, Amatullah Madeehah Tengku Mohd T. Awareness of teenagers on orthodontic treatment and fake braces in Malaysia. Published Online 2022:1–13. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1859609/v1

- 24.Kamarozaman DMS, Chiew SC, Wen JLQ, Pang YR, Bujang MA, Mat Shafiei R. Situation Analysis of Fake Braces among teenagers in Manjung District, Perak. Malays Dent J. 2021;1:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gazette. FAAGC (AGC) F. Malaysian Dental Act (Act 804).; 2018.

- 26.Nor NAM, Ming CJ, Bahar AD, Abidin HZ, Kamarudin Y. Challenges in curbing illegal orthodontics: a qualitative study on dental enforcement officers in Malaysia. Australas Orthod J. 2023;39(2):145–54. 10.2478/aoj-2023-0037. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghahramani A, de Courten M, Prokofieva M. The potential of social media in health promotion beyond creating awareness: an integrative review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1). 10.1186/s12889-022-14885-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Junhan C, Yuhan Weng. Social Media Use for Health purposes: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lucarotti PSK, Burke FJT. Factors influencing patients’ continuing attendance at a given dentist. Br Dent J 2015 2186. 2015;218(6):E13–13. 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariadas PA, Murthy U. Exploring the ramifications of a declining ringgit. Published. 2024. https://university.taylors.edu.my/en/student-life/news/2024/exploring-the-ramifications-of-a-declining-ringgit.html

- 31.Zhiran X. Cost Reduction in the Automobile Industry- Case Studies of the Chinese Market.; 2012. https://hh.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:607507/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- 32.Belgal P, Mhay S, Patel V, Nalliah RP. Adverse events related to Direct-To-Consumer Sequential Aligners—A study of the MAUDE Database. Dent J. 2023;11(7). 10.3390/dj11070174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Carter A, Stokes S. Availability of ‘Do-It-Yourself’ orthodontics in the United Kingdom. J Orthod. 2022;49(1):83–8. 10.1177/14653125211021607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meade MJ, Dreyer CW. An assessment of the treatment information contained within the websites of direct-to-consumer orthodontic aligner providers. Aust Dent J. 2021;66(1):77–84. 10.1111/adj.12810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alsaqabi F, Madadian MA, Pandis N, Cobourne MT, Seehra J. The quality and content of websites in the UK advertising aligner therapy: are standards being met? Br Dent J. 10.1038/s41415-023-5740-x [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.