Abstract

Background

Heterotrimeric G proteins are crucial signaling molecules involved in cell signaling, plant development, and stress response. However, the genome-wide identification and analysis of G proteins in castor (Ricinus communis L.) have not been researched.

Results

In this study, RcG-protein genes were identified using a sequence alignment method and analyzed by bioinformatics and expression analysis in response to salt stress. The results showed that a total of 9 G-protein family members were identified in the castor genome, which were classified into three subgroups, with the majority of RcG-proteins showing homology to soybean G-protein members. The promoter regions of all RcG-protein genes contained antioxidant response elements and ABA-responsive elements. Go enrichment analysis displayed that RcG-protein genes were involved in the G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, regulation of root development, and response to the bacterium. Real-time PCR showed varying responses of all RcG-protein genes to salt stress. RcGB1 was notably expressed in both roots and leaves under salt treatment, suggesting that it may be an essential gene associated with salt tolerance in the castor.

Conclusions

This study offers a theoretical framework for exploring G-protein function and presents potential genetic assets for improving crop resilience through genetic enhancement.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-024-11027-1.

Keywords: Heterotrimeric G protein, Ricinus communis, Bioinformatics, Gene expression analysis, Salt stress

Background

The heterotrimeric G proteins, composed primarily of α, β, and γ subunits, are widely found in eukaryotes and are classified as signaling proteins that participate in signal transduction pathways [1], which is a conservative extracellular signaling pathway that controls signal perception, signal transduction, hormonal response, and immune response [2]. Recent studies have shown that G proteins in plants play a role in regulating physiological processes like morphological development [3, 4], light signaling response [5, 6], and stress response [7–9]. These processes affect organ formation and overall plant growth and development. Within plants, the Gα subunit consists of typical Gα and atypical Gα subunits (XLGs). The Extra-large G proteins include a nuclear localization signal (NLS) segment and cysteine-rich structural domains at the beginning of the protein compared to the typical Gα subunit [10]. Seven continuous WD40 repeats are located at the C-terminal of the Gβ subunit, creating a β-helix structure [11]. The Gγ subunit is more abundant than the Gα and Gβ subunits, categorized into three types based on their C-terminal structures, determining the functional diversity of plant heterotrimeric G proteins [12].

In recent years, G-protein genes have been discovered in several plants like maize (Zea mays) [13], buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) [14], and mulberry (Morus alba) [15], which are crucial for the growth, development, and response to challenges. Studies have shown that AtGPA1 functions as a positive regulator of the phyA signaling pathway and is involved in the regulation of photosensitive pigment for seed germination [16]. Furthermore, AtGPA1 is equally crucial in the immune defense mechanism. Recognition of the flg22 peptide by plant defense cells triggers dephosphorylation at the Thr19 region of AtGPA1, leading to the activation of AtGPA1. This activation causes the G protein complex to dissociate, allowing AtAGB1 and AtAGG1 to engage in downstream immune signaling and control the immune response [17, 18]. In response to abiotic stress, AtAGB1 negatively regulates the ABA pathway and drought response by down-regulating the Atmpk6-related pathway and ABA biosynthesis [8].

Salt stress significantly inhibits plant growth and development. It hinders the development and differentiation of plant tissues and organs, leading to stunted growth or potential mortality [19]. Salt stress is categorized into two stages: osmotic stress in the early phase and ionic toxicity in the late phase. Osmotic stress impacts the closure of plant stomata, leading to a drop in photosynthetic rate and subsequent reduction in biomass. Following exposure to ionic stress, there is an increase in Na+ ions, which can have harmful effects by stimulating the generation of reactive oxygen species. Oxidative stress leads to membrane peroxidation and damages the plant’s cellular structure [20]. Previous studies have demonstrated that G proteins mediate the salt response via various channels, including the ROS pathway and short peptide signaling [21–24]. Yixin et al. [25] study how the root length of NbXLG3, NbXLG4, and NbXLG5 strains changes under various salt concentrations and finds that the Nbxlg3,5-L1 and Nbxlg3,5-L2 mutant strains show enhanced resistance to 200 mmol/L NaCl and normal resistance under the treatment of 250 mmol/L NaCl. The findings show that NbXLG3 and NbXLG5 have a negative regulation under salt stress in tobacco, contrasting with the positive effect of AtXLGs in Arabidopsis on salt stress, which indicates that G proteins react to challenges through varying mechanisms in various species [26, 27]. There is a synergistic interaction between AtAGB1 and FER (RLK FERONIA) in plants’ response to salt stress, potentially facilitated by salt-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [28]. The atypical Gγ protein (AT1) in sorghum plays a role in the crop’s reaction to alkali stress by affecting PIP2s to prevent their phosphorylation and H2O2 efflux. The mechanism is widely preserved in monocotyledonous plants, including cereals (Setaria italica), rice (Oryza sativa), and maize (Zea mays). Knocking out SbAT1 improves the crops’ ability to tolerate alkaline conditions, offering an enlightening point for identifying and developing salt-tolerant crops [29]. However, the biological functions of heterotrimeric G proteins in different species and their specific regulatory mechanisms remain unclear. Therefore, identifying G-protein family members provides a basis for investigating G-protein activities in growth and development, metabolic regulation, and environmental adaptation.

Castor (Ricinus communis L.) is considered one of the world’s top ten oil crops within the Euphorbiaceae family. Currently, downstream products derived from castor are extensively utilized in various fields [30]. With advancements in new energy technology, there is a yearly rise in market demand for castor oil and its derivatives [31]. A minimum of 500 K tons of castor seeds are required to satisfy market demand. However, local production is insufficient, totaling less than 300K tons [32]. The significant disparity between supply and demand has impacted the castor industry chain. Tongliao, situated in the eastern region of Inner Mongolia, is recognized as the ‘hometown of castor’ in China [33]. According to the latest report, it has been found that the area of saline-alkali cultivated land in Tongliao City is 3.8889 million acres, with heavy saline-alkali land comprising 11.23% of this total [34]. In soils with significant salinization, the roots and leaves of castor may incur damage, resulting in stunted growth and development, which hinders their ability to achieve genetic potential and directly impacts castor bean productivity [35]. This indicates that salt stress is a significant limiting factor affecting castor yield. Therefore, identifying salt-tolerant genes in castor beans and breeding novel salt-tolerant cultivars have emerged as a significant objective. Previous studies indicate that G proteins are crucial for plant growth and salt tolerance. On the whole, it is necessary and meaningful to study castor G-protein related research under salt stress.

So far, the studies of G proteins have been concentrated on specific species, and most studies have focused on the biological functions of a single gene, like Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) [36, 37], rice (Oryza sativa) [38, 39], and wheat (Triticum aestivum) [40, 41]. However, the identification and research of gene function of the G protein family in the castor have not been reported yet. In this study, we used bioinformatics to identify G-protein members in the castor bean genome and analyzed the physicochemical properties, chromosome localization, phylogenetic tree, promoter cis-acting elements, and protein interactions. Unlike previous similar studies, the study focused on analyzing the expression pattern of RcG-protein genes in salt-tolerant castor and salt-sensitive castor. The aim was to provide a reference basis for further functional characterization of RcG-protein genes involved in salt stress.

Materials and methods

Identification of RcG-proteins in the castor genome

The castor genome sequence, protein sequence, and annotation data were downloaded from the Oil Plants Database (http://oilplants.iflora.cn). G protein sequences from Arabidopsis were acquired from the TAIR database (Araport11, https://www.arabidopsis.org). Maize G protein sequences were obtained from the MaizeGDB Database (https://maizegdb.org/). G protein sequences of soybean and tomato were obtained from Phytozome (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/). Rice G protein sequences were obtained from Rice Database Oryzabase (https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/rice/oryzabase/). In addition, Gα (PF00503), Gβ (PF00400), and Gγ (PF00631) were downloaded from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org). Candidate sequences were analyzed using HMMER search and BLAST with a significance threshold of E-value ≤ e− 5. To determine the accuracy of the candidate members, the protein sequences were submitted to Pfam and Smart (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) to remove redundant and non-conserved sequences. The candidate members were named RcG-proteins according to their chromosomal location.

Sequence analysis and chromosome location of RcG-proteins

The number of amino acids, isoelectric point, and molecular weight of RcG-proteins were analyzed using the ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) [42]. The WoLF PSORT tool (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) was used to forecast the subcellular positioning of RcG-proteins [43]. The chromosomal data of the RcG-protein genes was extracted from the castor genome annotation data, then evaluated and mapped for chromosomal positioning using TBtools [44].

Phylogenetic analysis of RcG-proteins

The G-proteins from Arabidopsis, maize, tomato, rice, and soybean were aligned using MEGA11. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining Method (NJ), and Bootstrap analysis was set to 1000 replicates [45].

Analysis of RcG-proteins motifs, conserved domains, and gene structures

Conserved motifs of RcG-proteins were predicted using the MEME online tool (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/ meme) [46]. Conserved domains were analyzed using NCBI-CDD Search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/) [47]. The exon/intron numbers of RcG-protein genes were illustrated based on the castor genome annotation data. All were visualized using TBtools.

Analysis of cis-acting elements in RcG-protein genes promoters

To predict the potential biological functions of RcG-protein genes, 2000 bp upstream sequences of the translation start site were searched to predict the cis-acting elements in their promoters using the PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/ht-ml/) [48].

Analysis of protein-protein interaction network

The String website (https://string-db.org/) and Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/download.html) assessed the castor G-protein interaction data and anticipated probable connections among family members [49, 50].

Expression analysis of RcG-protein genes in different tissues and under salt stress

To understand how RcG-protein genes regulate plant growth and development and respond to salt stress, the global expression profiles of RcG-protein genes were examined based on Brown’s RNA-seq data [51]. According to the research, these tissues included germinating seeds incubated in darkness for 3 days, developing male flowers, endosperm at stages II/III (endosperm free-nuclear stage), and stages V/VI (onset of cellular endosperm development).

Castor bean inbred lines were obtained from the key laboratory of castor breeding in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, Inner Mongolia Minzu University, China. Based on the evaluation of salt-tolerant germplasm, “2129” (salt-tolerant) and “Tongbi 5” (salt-sensitive) were selected. Criteria for screening: Salt index (Salt index (SI) is calculated as SI (%)=[(1×N1 + 2×N2 + 3×N3 + 4×N4)/(S×4)] × 100) was used as the seedling salt tolerance screening criterion of castor bean in the pre-laboratory stage, where S represents the total number of treated plants, and where N is the number of seedlings in salinity class. Castor seedlings with four leaves were chosen for salt treatment, and a water control was implemented 24 h before the salt treatment to enhance the diffusion of saltwater in the desiccated soil. Two hundred milliliters of 200 mmol/L NaCl solution (11.688 g of NaCl diluted in 1 L of distilled water) was applied above the castor leaves, while an equivalent volume of distilled water served as the control group. Sampling was carried out at 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h after salt stress treatments. Roots, stems, and leaves from different time treatments were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C in a refrigerator.

The total RNA of castor was extracted using the Trizol method, and the extracted RNA was subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and detected. Real-time PCR was used to examine the relative expression of RcG-protein genes in roots and leaves at various treatment durations. The RcSKIP gene was used as the internal reference gene, and the analysis was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method [52]. The primers for the RcG-protein genes and RcSKIP gene were listed in Table S1.

Results

Identification and analysis of RcG-proteins

Based on BLAST and HMM combined analysis, nine G-protein family members were identified in the castor genome, and their physicochemical properties were analyzed (Table 1). The results indicated that the castor G-protein family members consisted of five Gα, one Gβ, and three Gγ, with Gα including one RcGA1 and four extra-large Gα proteins (RcXLGs). The amino acid numbers of RcG-proteins ranged from 106 (RcGG3) to 1546 (RcXLG3) aa; the molecular weights ranged from 12.17 to 176.04 kD; the theoretical isoelectric points ranged from 4.35 (RcGG1)-6.88 (RcGB1), indicating that they might be acidic proteins functioning in weakly acidic cellular environments. RcGB1 was the only protein with an instability index below 40, while the rest of the members were considered unstable. As the average hydrophilicity coefficients were below 0, RcG-proteins were deemed hydrophilic. According to the results of subcellular positioning, RcG-proteins were mainly distributed in the nucleus, and the remaining few were distributed in the chloroplasts (RcGA1, RcGG3) and the cytoplasm (RcGG1).

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of G-protein family members in castor: an in-depth overview of amino acid numbers, molecular weight, isoelectric point, instability index, grand average of hydropathicity, subcellular localization, and conserved domains

| Gene name | Gene ID | Number of Amino Acid | Molecular Weight | pI | Instability Index | Grand Average of Hydropathicity | Subcellular localization | Pfam structure identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (KDa) | ||||||||

| RcGA1 | Rc03T005588.1 | 392 | 45.58 | 5.84 | 46.47 | -0.544 | chloroplast | Gprotein_alpha_subunit |

| RcXLG1 | Rc03T006762.1 | 260 | 30.34 | 4.93 | 47.78 | -0.532 | Nucleus | Gprotein_alpha_subunit |

| RcXLG2 | Rc05T011477.3 | 929 | 104.26 | 5.71 | 46.62 | -0.472 | Nucleus | Gprotein_alpha_subunit |

| RcXLG3 | Rc05T009920.1 | 1546 | 176.04 | 6.11 | 48.07 | -0.368 | Nucleus | Gprotein_alpha_subunit |

| RcXLG4 | Rc09T021771.1 | 917 | 102.06 | 5.18 | 45.65 | -0.423 | Nucleus | Gprotein_alpha_subunit |

| RcGB1 | Rc05T010514.1 | 377 | 40.83 | 6.88 | 30 | -0.163 | Nucleus | Guanine_nucleotide_bsu |

| RcGG1 | Rc01T000851.1 | 108 | 12.17 | 4.35 | 65.45 | -0.571 | cytoplasm | G protein_gamma-like_domin |

| RcGG2 | Rc02T004071.1 | 113 | 12.38 | 5.66 | 64.05 | -0.417 | Nucleus | G protein_gamma-like_domin |

| RcGG3 | Rc06T013310.1 | 106 | 12.18 | 5.43 | 52.86 | -0.812 | chloroplast | G protein_gamma-like_domin |

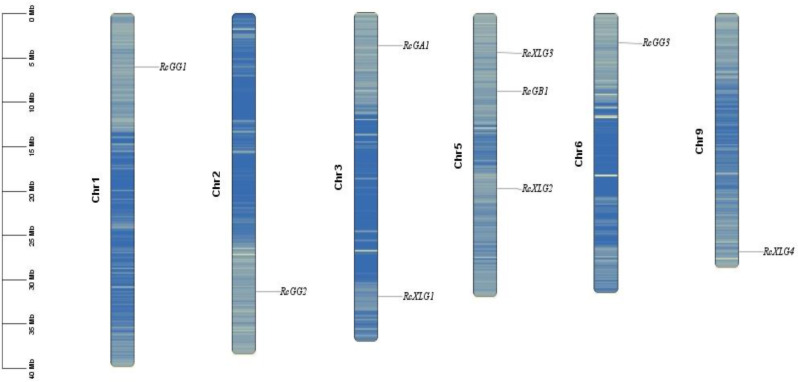

Chromosomal localization analysis of RcG-protein genes

According to the castor genome annotation, RcG-protein genes were located on six different chromosomes (Chr 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9) (Fig. 1). Chr5 had the highest number of family members (RcXLG3, RcGB1, and RcXLG2), Chr3 had RcGA1 and RcXLG1, while the other chromosomes each had one member. This study identified no duplicated genes resulting from gene duplication events in the castor G protein family.

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal distribution of RcG-protein genes in castor. Chromosome numbers were displayed in black font on the side. The RcG-protein gene was shown in the black italicized font on the side. The scale of the chromosome was in millions of bases (Mb)

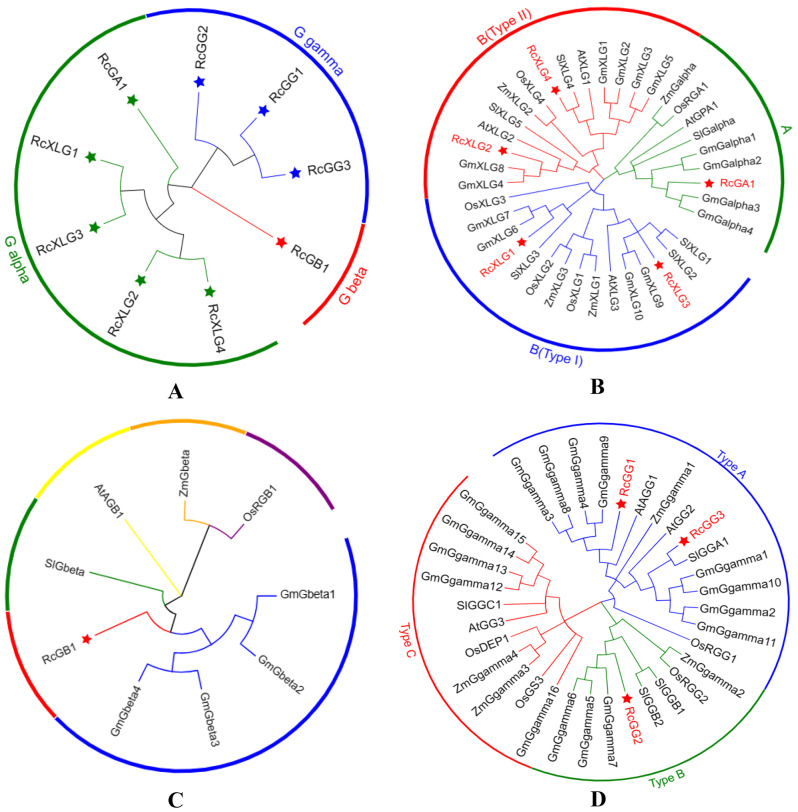

Evolutionary analysis of RcG-proteins

To investigate the function and evolutionary relationship of RcG-proteins, monocotyledonous plants (maize, rice) and dicotyledonous plants (soybean, Arabidopsis, tomato) were selected respectively for constructing phylogenetic trees (Fig. 2). RcG-proteins were classified into three subfamilies: Gα, Gβ, and Gγ, each with varying affinities (Fig. 2A). The results indicated a close relationship between RcGA1 and Gmalpha3, Gmalpha4 in soybean. Additionally, the extra-large G proteins consisted of four members (RcXLG1-4), which were divided into two categories: RcXLG1 and RcXLG3 were classed as type I, while RcXLG2 and RcXLG4 were categorized as type II (Fig. 2B). RcXLG1 and RcXLG2 were grouped along with GmXLG6 and GmXLG7, and GmXLG4 and GmXLG8, respectively. RcXLG4 was grouped with SlXLG4. The Gγ subunit proteins were categorized into three types (Type A, Type B, and Type C) according to their C-terminal sequences. RcGG1 and RcGG3 were classified in the Type A group, while RcGG2 was classified in the Type B group. None of the three RcGγ proteins were in the Type C group, possibly due to homologous gene loss in the evolutionary process (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

The phylogenetic analysis was conducted to explore the relationships among G proteins in Ricinus communis (Rc), Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Zea mays(Zm), Oryza sativa(Os), Solanum lycopersicum(Sl), and Glycine max(Gm). The Neighbor Joining (NJ) method used 1000 bootstrap replicates and was applied to draw the phylogenetic trees. A: Phylogenetic tree of RcG-proteins. B: Phylogenetic tree of Gα proteins of 6 plant species. C: Phylogenetic tree of Gβ proteins of 6 plant species. D: Phylogenetic tree of Gγ proteins of 6 plant species. Distinct groups were indicated by branches colored differently. Red stars indicated castor G proteins

Analysis of motifs, conserved domains, and gene structures in RcG-proteins

The three subfamily members of the RcG-proteins were analyzed using the motif, conserved domain, and gene structure analysis to gain a deeper understanding (Fig. S1). The results indicated that the motifs of RcG-proteins exhibited diversity. However, motifs within the same subfamily were largely similar in composition. Motif 1 and Motif 2 were prevalent in the Gα subfamily, indicating that these motifs represent conserved sequences among Gα members (Fig. S1A). Motif 3 and Motif 8 were exclusive to RcXLGs, differentiating between typical Gα and atypical Gα (Fig. S1A). Gβ contained repeated motifs for Motif 1-5 (Fig. S1B). Within the Gγ subfamily, Motif 1, Motif 2, and Motif 3 showed a high level of conservation, presumably closely related to their biological functions (Fig. S1C). According to conserved structural analysis results, all Gα subfamily members contained G-alpha binding domains, Gβ subfamily members had WD40 domains, and all Gγ subfamily members, except RcGG2, contained G-gamma domains. Gene structure analysis revealed significant variations among subfamilies of RcG-protein genes in terms of exon and intron numbers. Exon numbers ranged from 2 (RcXLG1) to 12 (RcGA1), while intron numbers ranged from 3 (RcGG1, RcGG3) to 13 (RcGA1). However, there was less diversity in the number of members within the same subfamily, indicating a higher degree of similarity that might suggest similar biological functions.

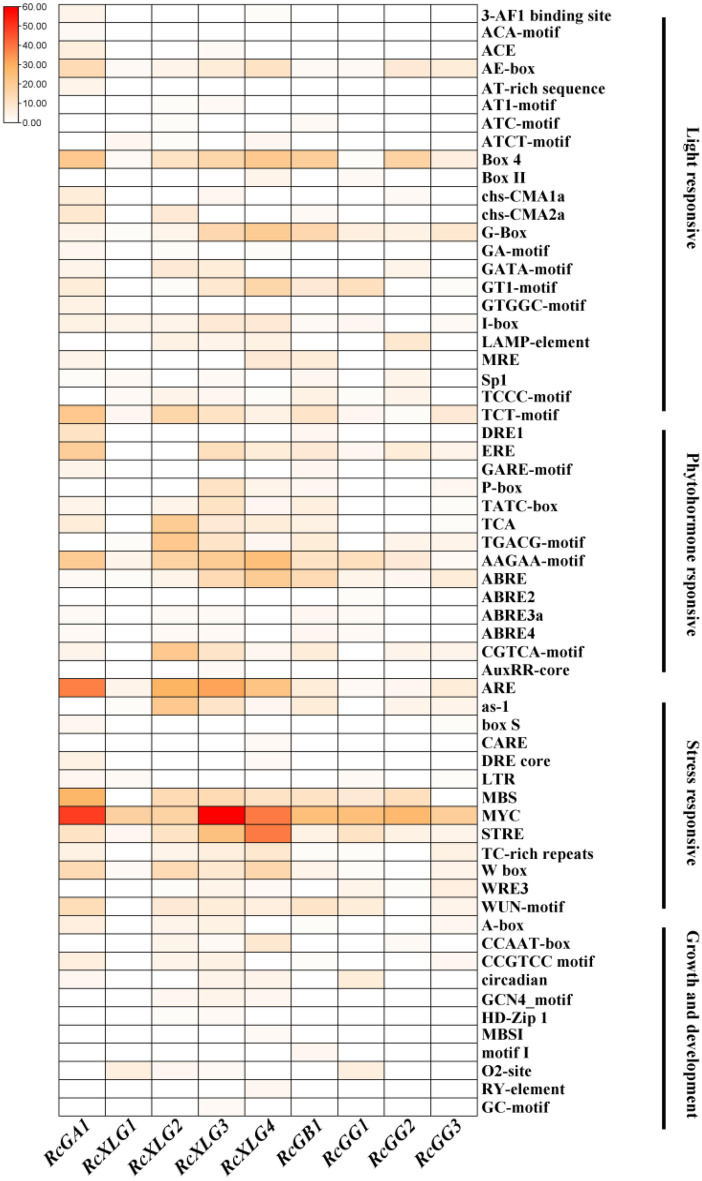

Analysis of cis-acting elements in the RcG-protein genes promoters

The existence and roles of cis-acting elements in the promoters of RcG-protein genes were investigated utilizing the PlantCARE online tool and TBtools. The results showed that a total of 61 cis-acting elements were found in the promoter region of RcG-protein genes. These elements fell into four categories, including light response, hormone response, stress response, and plant growth and development (Fig. 3). The RcG-protein genes had the most members associated with stress response elements, followed by hormone response elements and light response elements, with the fewest members related to plant growth and development. Among the stress response elements, antioxidant response element (ARE), damage-inducing element (WRE3, WUN-motif), defense and stress response elements (TC-rich repeats), drought-inducing element (MBS), and low-temperature response element (LTR) were included. The results indicated that all RcG-protein genes possessed antioxidant response elements, implying their potential function in neutralizing reactive oxygen species and safeguarding cells from oxidative harm. Various hormone response elements were present, such as abscisic acid (ABRE, ABRE2, ABRE3a, ABRE4, AAGAA-motif), methyl jasmonate (TGACG-motif, CGTCA-motif), gibberellin (P-box, TATC-box, GARE-motif), ethylene (ERE), and salicylic acid (TCA), etc. The investigation showed that all RcG-protein genes contained components associated with ABA hormone regulation, indicating that RcG-protein genes might play a role in ABA-mediated responses to environmental stress. Among the plant growth and development-related elements, including those involved in the regulation of zein metabolism regulation (O2-site), circadian control (circadian), and seed-specific regulation (RY-element), it was noteworthy that only RcXLG4 contained seed-specific regulatory elements, which was hypothesized to play an essential role in the regulation of seed growth possibly. In conclusion, RcG-protein genes may be involved in castor growth and development, hormone regulation, adversity stress, and light regulation.

Fig. 3.

Cis-acting elements analysis of the promoter region of RcG-protein genes. The PlantCARE software was used to analyze the 2000 bp DNA sequence upstream of RcG-protein genes. The heat map represented the number of elements. The color scale changes represented an increase in the number of cis-acting elements

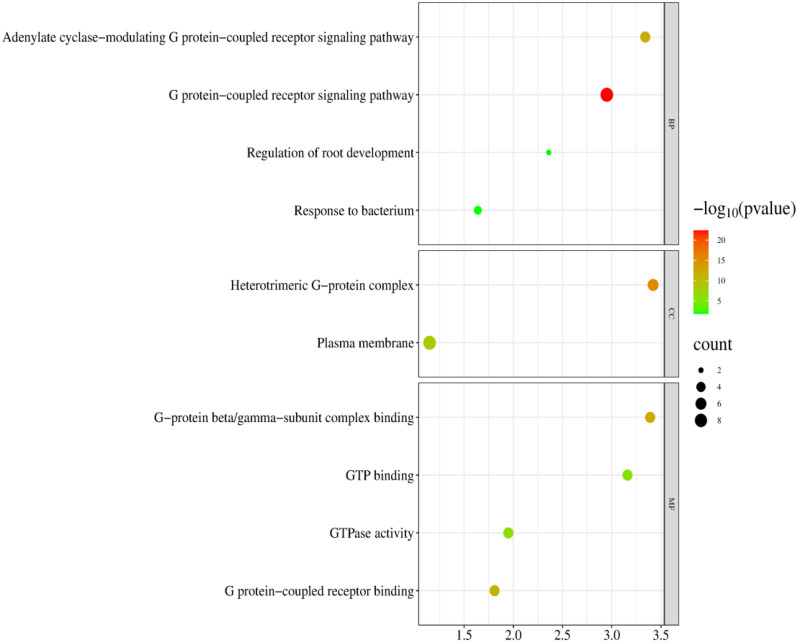

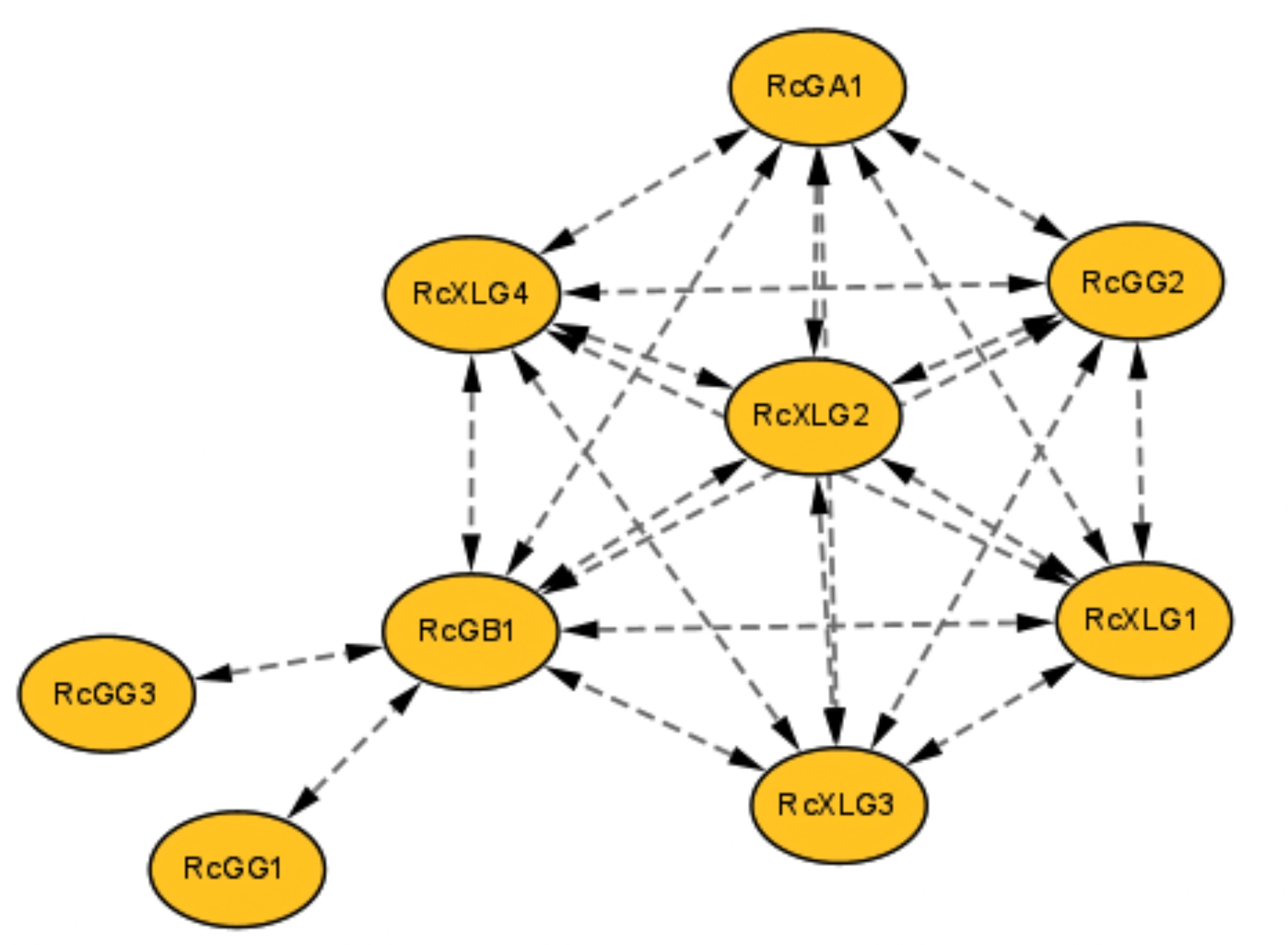

Analysis of protein-protein interactions

Protein interactions are a crucial process in living organisms, which influences various biological functions through interactions between proteins to form complexes or multiprotein networks. The results showed that, as shown in Fig. 4, there were nine nodes in the whole interactions network, and there were 23 groups of protein interactions between the nodes. RcGγ and RcGβ interacted to create a dimerization complex, which may be believed to enhance signaling. Moreover, RcGα and RcGβ subfamily proteins possibly interacted and collaborated in regulating a specific biological function. The GO enrichment analysis showed that RcG-protein genes were enriched in biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF) (Fig. 5). The biological process branch primarily emphasized G protein signaling (GO:0007188 and GO:0007186), regulating root development (GO:2000280), and responding to bacterial hazards (GO:0009617).

Fig. 4.

Protein-protein interaction network of heterotrimeric G-protein family members in castor. Interaction networks were constructed by using the STRING database. The yellow nodes represented castor G proteins. The double-arrowed dotted line represented the existence of an interaction between two proteins

Fig. 5.

GO enrichment analysis of RcG-protein genes. The enrichment results were classified into three categories: Biological Process, Cellular Component, and Molecular Function. The color scale represented the size of the p-value. The size of the circle represented the amount of enrichment

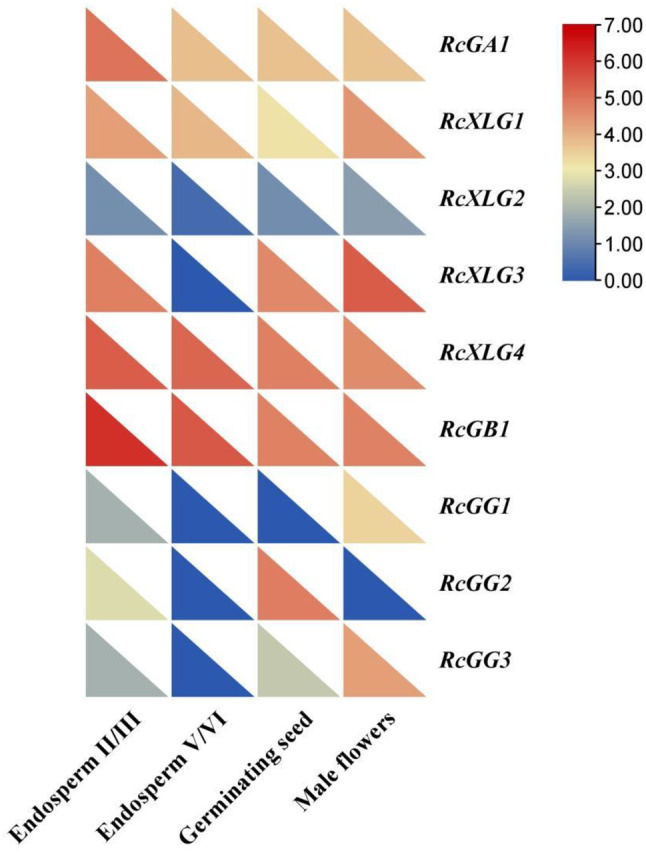

Analysis of tissue-specific expression of the RcG-protein genes

Based on the analysis of RNA-seq data, the expression patterns of RcG-protein genes during different developmental stages (germinating seeds, endosperm development II/III, endosperm development IV/V) and the tissue (male flower) were studied. The results revealed significant differences in the expression levels of RcG-protein genes at different developmental phases (Fig. 6). RcXLG4 and RcGB1 showed high expression levels at various developmental stages. RcGG1, RcGG2, and RcGG3 exhibited low expression levels in endosperm IV/V compared to the other two phases (endosperm IV/V and seed germination), which displayed that the mechanisms played by members of the Gγ family may be diverse at different stages of seed development. All members except RcGG2 were expressed in the male flowers, with RcXLG3 exhibiting the highest expression level. The expression patterns of RcGA1, RcGG1, RcGB1, RcXLG1, and RcXLG4 were relatively consistent in between RNA-Seq and Real-time PCR analysis, indicating the reliability of the RNA-Seq data (Fig S2).

Fig. 6.

Heatmap of expression levels for the RcG-protein genes in various tissues of castor (germinating seeds, male flowers, endosperm development II/III, endosperm development V/VI). The normalization of transcript levels for each specific RcG-protein across diverse tissues was performed using fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) values as a standard reference. The color scale changes indicated the difference in expression levels for each gene

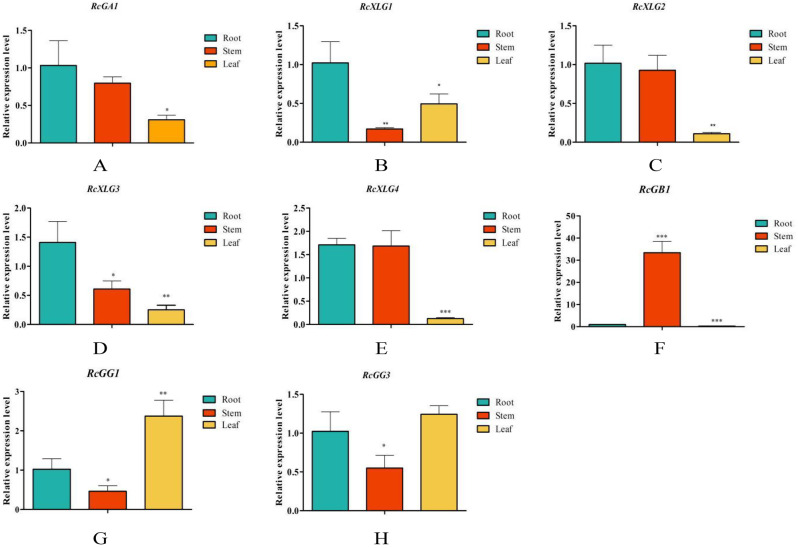

Further analysis using RT-qPCR investigated the expression patterns of the G-protein family members in the roots, stems, and leaves of castor (Fig. 7). The results indicated that the majority of RcG-protein genes exhibited tissue-specific expression, with a higher expression level in the roots or leaves of castor, and the expression patterns were analogous within the same subfamily. For example, the G protein γ subunits (RcGG1 and RcGG3) were expressed at the highest levels in the leaves; the G protein α subunits (RcGA1, RcXLG1, and RcXLG3) were comparatively more highly expressed in the roots. Furthermore, The member of the G protein β subfamily was distinct from the other two subfamilies, with RcGB1 exhibiting significantly high expression in the stems.

Fig. 7.

qRT-PCR analysis of RcG-protein genes in roots, stems, and leaves of castor. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent replicates. The X-axis showed different tissues, and the Y-axis represented relative expression level. T-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) was used to determine the significance of the differences with roots. Different colors represented different tissues of the castor

Expression patterns of the RcG-protein genes under salt stress

Analyzing the variations in physiology, biochemistry, and molecular processes among closely related species, distinct varieties, and ecotypes in response to salt stress might provide a more thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying salt tolerance in plants [53].

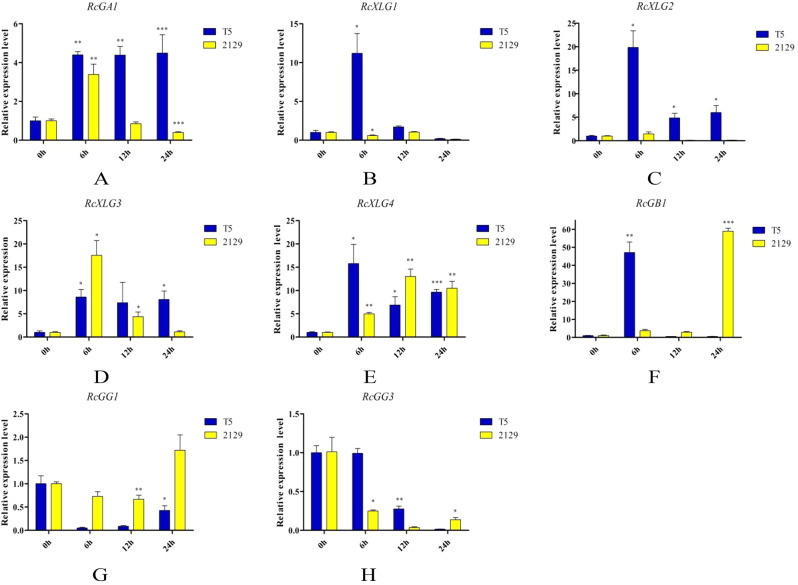

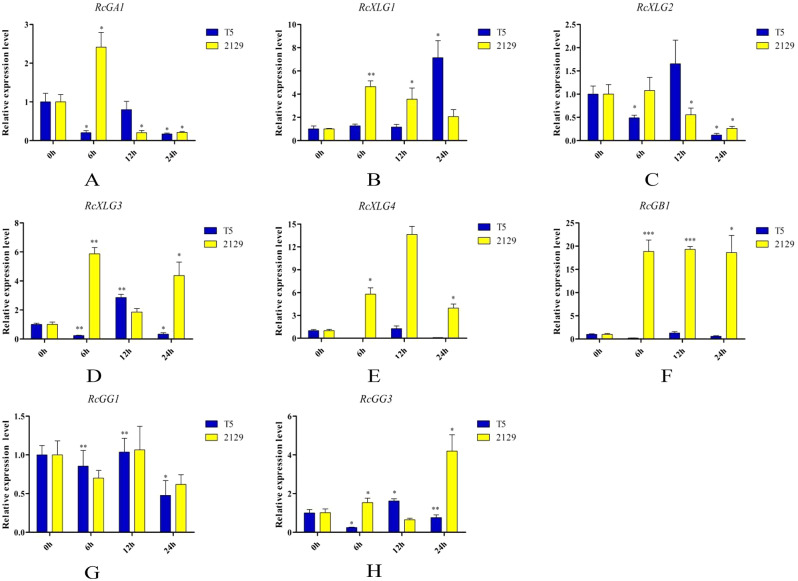

To better understand the potential functions of RcG-protein genes in different salt-tolerant castor varieties, the salt-tolerant variety “2129” and the salt-sensitive “Tongbi 5” were chosen. The gene expressions in leaves and roots were analyzed at different salt treatment times (Figs. 8 and 9). The results indicated that RcG-protein genes exhibited varying responses to salt stress, with distinct expression patterns observed in different salt-tolerant varieties and tissue types, showing that RcG-protein genes might have different roles and functions. For instance, RcGA1 was initially upregulated and subsequently down-regulated in the roots of both varieties. However, it consistently showed up-regulation in the leaves of “Tongbi 5” and displayed an up-regulation followed by a down-regulation pattern in the leaves of “2129”. RcXLG4 was strongly expressed in roots of the salt-tolerant variety “2129” after 12 h of salt treatment, while RcGB1 was upregulated in both leaves and roots. In the salt-sensitive variety “Tongbi 5”, RcXLG1 showed high expression in salt-treated roots and leaves, while RcGB1 had the highest expression in leaves treated for 6 h. From these two varieties with different tolerances, RcGB1 was significantly induced to be highly expressed under salt stress, indicating its potential role in salt tolerance in castor. These results potentially suggested the involvement of G-protein genes in the response of castor to salt stress.

Fig. 8.

qRT-PCR analysis of RcG-protein genes in leaves under salt stress. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent replicates. The X-axis showed different treatment times, and the Y-axis represented relative expression level. T-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) was used to determine the significance of the differences with the 0 h leaves. Different colors represented different varieties of castor

Fig. 9.

qRT-PCR analysis of RcG-protein genes in roots under salt stress. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent replicates. The X-axis showed different treatment times, and the Y-axis represented the relative expression level. T-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) was used to determine the significance of the differences with the 0 h roots. Different colors represented different varieties of castor

Discussion

Heterotrimeric G proteins, as a signaling molecule, are involved in various signaling pathways and play a significant part in the plant life cycle [54]. This study discovered nine G-protein family members divided into three subfamilies (α, β, and γ), consistent with findings in previous studies on maize [12, 13] and buckwheat [13, 14]. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, most of the members of RcG-proteins were more homologous to GmG-proteins. However, the number of RcG-proteins was lower than the number of soybean G proteins. It was hypothesized that this difference could be due to differential expansion events during plant evolution or could be affected by incomplete annotation of the castor genome [55]. Alterations in gene structure and its stability are crucial factors in the evolution of gene families [56]. The structures of RcG-protein genes were analyzed, revealing similar exon distribution and length within subgroups but variations in sequence distribution among the three subfamilies, possibly attributed to differences in intron and UTR region lengths. The motif analysis showed that the motif order of RcXLGs and RcGGs was highly conserved, with similar motif positions, suggesting that they might remain unchanged throughout evolution. By chromosomal localization analysis, it was found that there were no duplicated genes caused by gene duplication events in RcG-protein genes, illustrating that the members of the G-protein family in castor may have relatively separate evolutionary ties.

Gene expression control is intricately linked to cis-acting elements found in gene promoters. In this study, we analyzed the promoter region of RcG-protein genes that contained photosynthesis-related elements such as Box 4 and AE-box, antistress-related elements such as TC-rich repeats and WUN-motif, and growth and development-related elements such as O2-site and RY-element. This suggested that RcG-protein genes might be crucial for stress response and the growth and development of plants. It is worth noting that all RcG-protein genes contained ABRE (ABA-response elements) cis-acting elements, which were essential components of the ABA hormone signaling pathway. Proteins interacting with the ABRE element are AREBs or ABFs (ABRE-binding factors), which belong to class A bZIP-type transcription factors and play a crucial role in the ABA hormone signaling system [57, 58]. In this study, only RcGA1 and RcGB1 were identified to contain DRE cis-acting elements that primarily functioned in ABA-independent pathways. It could be inferred that RcGA1 and RcGB1 were influenced by the regulation or interactive activation of two ABA-dependent and non-dependent signaling pathways during stress, while RcXLGs and RcGGs might be primarily regulated by ABA-dependent signaling pathways. The osmotic stress, leading to a quick buildup of ABA, is induced by cold, drought, and salt stress [59]. The ABA signaling pathway comprises four essential components that create a double-negative regulatory system: (PYR/PYL/RCAR-|PP2C-|SnRK2-ABF/AREB) [60]. MaABI1/2 and MaSnRK2.1/2.4 in mulberry can directly interact with the G protein γ subunit, indicating that the G protein γ subunit improves drought stress by boosting the ABA signaling pathway [61]. It was speculated that RcG-protein genes might improve castor response to adversity tolerance by regulating the ABA pathway and gene expression. However, its regulatory mechanism needs to be further investigated.

Enrichment analysis can illustrate the significance of genes in particular biological processes and deduce their potential functions. In this study, RcG-protein genes were predominantly enriched in the G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, serving as intermediaries in the signaling cascade. The pathway has been reported for regulating cold tolerance mechanisms and its impact on crop output and quality [62]. In addition, RcG-proteins genes were enriched in the regulation of root development. There is a notable decrease in lateral roots in Atgpa1 mutant strains, while Atagb1 mutant strains showed a significant increase in lateral roots. Besides, AtGPA1 relies on AtAGB1 to control cell proliferation [63]. RcG-protein genes likely had a vital role in root system growth and development, impacting the growth traits of castor plants. Combining RNA-seq expression profiles with qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated significant differences in the expression of the RcG-protein genes among different tissues, implying potential differences in their functions in castor growth and development. For example, the expression levels of RcXLG4 and RcGB1 during the seed development stage were markedly elevated compared to other RcG-protein genes, indicating that these two genes may be essential for castor seed development. During the seedling stage of castor, the majority of G protein family members exhibited elevated expression levels in the roots or leaves relative to other tissues. Heterotrimeric G proteins have been shown to be involved in regulating various growth and developmental processes, such as seed germination, plant nutrient growth, and stomatal movement [11]. It can be inferred that the expression pattern of RcG-protein genes in various tissues may be linked to plants’ regulatory role in normal growth and development.

Salt stress is a significant environmental element that constrains plant development and productivity. As a crucial regulatory factor in plant growth and development, the G-protein genes family has been reported to respond to salt stress in numerous species. For example, In Arabidopsis, AtAGB1 is involved in the S1P and S2P-mediated hydrolysis of the bZIP17 protein during salt stress, hence controlling the activation of salt-responsive gene expression and improving the plant’s tolerance to salt stress [64]. Heterologous expression of MaGα can diminish the salt stress tolerance of transgenic lines [15]. In this study, under salt stress, the transcriptional expression levels of the genes encoding RcGα, RcGβ, and RcGγ were upregulated to varied extents, consistent with the results from species such as Arabidopsis and rice [65–67]. Under salt stress treatment, the transcription levels of RcGA1, RcXLG4, and RcGB1 in the roots and leaves were upregulated more than twofold, implying that these genes may be significant in the control of salt stress. Notably, most RcG-protein genes were significantly elevated following 6 h of salt treatment. This may be attributed to the stress response induced by salt stress in the first phase, which activates the expression of castor G-protein genes. However, further investigation is required to validate this hypothesis. Interestingly, this work revealed that the expression level of the RcGB1 gene was markedly induced in two distinct salt-tolerant types and tissues compared to other family members, suggesting that salt stress may substantially enhance RcGB1 gene expression. It was reasonable to speculate that RcGB1 gene may positively regulate the salt tolerance of castor under salt stress. A research examines the mutation analysis of different parts of G protein signaling and discovered that AtAGB1 has a role in Na+ efflux and transport, influencing plant salt resistance by controlling the expression of proline synthesis, oxidative stress, and other relevant genes [67]. The overexpression of RGB1 results in decreased electrolyte leakage in transgenic lines, increased chlorophyll levels, enhanced chlorophyll concentrations, and elevated expression of some antioxidant enzyme-related genes (such as SOD and POD) [68, 69]. Combined with previous studies, it can be inferred that the RcGB1 gene may regulate a certain signaling pathway, influencing the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes and augmenting the plant’s capacity to eliminate reactive oxygen species (ROS), therefore strengthening the plant’s tolerance to salt stress. However, the restriction should be noted, which the precise characteristics of this pathway in castor remained unclear. Consequently, it is imperative to elucidate the connection between RcGB1’s role in the regulation of the ROS pathway and its influence on the salt tolerance of the castor.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study discovered nine G-protein members in the castor genome and analyzed various aspects, such as physicochemical properties, conserved motifs, gene structures, and protein interaction networks. We also investigated the expression patterns of RcG-protein genes in different tissues and under salt stress, indicating that these genes may play roles in castor growth and stress response. Additionally, the work discovered that RcGB1 was induced to high expression in two different salt-tolerant castor varieties, suggesting it might be a key salt-tolerant gene. Overall, these results enrich the understanding of the potential functions of RcG-protein genes, which provide a foundation for further studies on genetic improvement of the castor yield and salt resistance.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31760399; 32060493) and projects of Inner Mongolia Collaborative Innovation Center for Castor Industry (MDK2023083, MDK20230779, MDK2023077) for this project.

Author contributions

JXZ conceived and designed the experiments. MBF performed the experiments. MBF, JYL, TJZ, HYH, SYL, ZBH, XYW, and JXZ analyzed the data. MBF and JXZ wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31760399; 32060493) and projects of Inner Mongolia Collaborative Innovation Center for Castor Industry (MDK2023083, MDK20230779, MDK2023077).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and can be found in Supplementary Tables S1, Tables S2, Figure S1, and Figure S2. The RNA-seq data analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under BioProject PRJEB2660 (Accession: ERX021379, ERX021378, ERX021377, ERX021376, ERX021375).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhong CL, Zhang C, Liu JZ. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling in plant immunity. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(4):1109–18. 10.1093/jxb/ery426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choudhury SR, Pandey S. Specific subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins play important roles during nodulation in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2013;162(1):522–33. 10.1104/pp.113.215400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ullah H, Chen JG, Young JC, Im KH, Sussman MR, Jones AM. Modulation of cell proliferation by heterotrimeric G protein in Arabidopsis. Science. 2001;292(5524):2066–9. 10.1126/science.1059040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bommert P, Je BI, Goldshmidt A, Jackson D. The maize Gα gene COMPACT PLANT2 functions in CLAVATA signalling to control shoot meristem size. Nature. 2013;502(7472):555–8. 10.1038/nature12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto H, Matsui M, Deng XW. Overexpression of the heterotrimeric G-protein alpha-subunit enhances phytochrome-mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13(7):1639–52. 10.1105/tpc.010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrero-Serrano Á, Su Z, Assmann SM. Illuminating the role of the Gα heterotrimeric G protein subunit, RGA1, in regulating photoprotection and photoavoidance in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(2):451–68. 10.1111/pce.13113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magdalena Delgado-Cerezo, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Escudero V, Miedes E, Fernández PV, Jordá L, Hernández-Blanco C, Sánchez-Vallet A, Bednarek P, Schulze-Lefert P, Somerville S, Estevez JM, Persson S, Molina A. Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G-protein regulates cell wall defense and resistance to necrotrophic fungi. Mol Plant. 2012;5(1):98–114. 10.1093/mp/ssr082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu DB, Chen M, Ma YN, Xu ZS, Li LC, Chen YF, Ma YZ. A G-protein β subunit, AGB1, negatively regulates the ABA response and drought tolerance by down-regulating AtMPK6-related pathway in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1):e0116385. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakravorty D, Gookin TE, Milner MJ, Yu Y, Assmann SM, Extra-Large G. Proteins Expand the Repertoire of subunits in Arabidopsis Heterotrimeric G protein signaling. Plant Physiol. 2015;169(1):512–29. 10.1104/pp.15.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CY. Identification of the genes involved in G-protein signaling in mulberry and their regulation in response to abiotic stresses. Southwest University; 2019.

- 11.Tiwari R, Bisht NC. The multifaceted roles of heterotrimeric G-proteins: lessons from models and crops. Planta. 2022;255(4):88. 10.1007/s00425-022-03868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trusov Y, Chakravorty D, Botella JR. Diversity of heterotrimeric G-protein γ subunits in plants. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:608. 10.1186/1756-0500-5-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng XX, Wang YP, Zhang RY, Wang Z. Genome-wide Identification and Expression Analysis of G Protein Gene Family in Maize. Molecular Plant Breeding. 2024;1–13. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/46.1068.S.20231206.1844.031.html

- 14.Liu CY, Ye XL, Zou L, Xiang DB, Wu Q, Wan Y, Wu XY, Zhao G. Genome-wide identification of genes involved in heterotrimeric G-protein signaling in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) and their potential roles in regulating fruit development. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;171:435–47. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu CY, Xu YZ, Fan W, Long DP, Cao BN, Xiang ZH, Zhao AC. Identification of the genes involved in heterotrimeric G-protein signaling in mulberry and their regulation by abiotic stresses and signal molecules[J]. Biol Plant. 2018;62(2):277–86. 10.1007/s10535-018-0779-2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botto JF, Ibarra S, Jones AM. The heterotrimeric G-protein complex modulates light sensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana seed germination. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85(4):949–54. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue J, Gong BQ, Yao X, Huang X, Li JF. BAK1-mediated phosphorylation of canonical G protein alpha during flagellin signaling in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2020;62(5):690–701. 10.1111/jipb.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tunc-Ozdemir M, Urano D, Jaiswal DK, Clouse SD, Jones AM. Direct modulation of Heterotrimeric G protein-coupled signaling by a receptor kinase complex. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(27):13918–25. 10.1074/jbc.C116.736702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang W, Ma X, Wan P, Liu L. Plant salt-tolerance mechanism: a review. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495(1):286–91. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy SJ, Negrão S, Tester M. Salt resistant crop plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;26:115–24. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urano D, Colaneri A, Jones AM. Gα modulates salt-induced cellular senescence and cell division in rice and maize. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(22):6553–61. 10.1093/jxb/eru372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Y, Assmann SM. The heterotrimeric G-protein β subunit, AGB1, plays multiple roles in the Arabidopsis salinity response. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38(10):2143–56. 10.1111/pce.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swain DM, Sahoo RK, Srivastava VK, Tripathy BC, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Function of heterotrimeric G-protein γ subunit RGG1 in providing salinity stress tolerance in rice by elevating detoxification of ROS. Planta. 2017;245(2):367–83. 10.1007/s00425-016-2614-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng P, Gao YD, Li Z, Yu YW, Qin H, Guo Y, Huang RF, Wang J. Proteomic analysis of a rice mutant sd58 possessing a Novel d1 allele of Heterotrimeric G protein alpha subunit (RGA1) in salt stress with a focus on ROS scavenging. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(1):167. 10.3390/ijms20010167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li YX, Zhang Q, Gong LJ, Kong J, Wang XD, Xu GY, Chen XJ, Dou DL, Liang XX. Extra-large G proteins regulate disease resistance by directly coupling to immune receptors in Nicotiana Benthamiana. Phytopathol Res. 2022;4(49). 10.1186/s42483-022-00155-9.

- 26.Ding L, Pandey S, Assmann SM. Arabidopsis extra-large G proteins (XLGs) regulate root morphogenesis. Plant J. 2008;53(2):248–63. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urano D, Maruta N, Trusov Y, Stoian R, Wu QY, Liang Y, Jaiswal DK, Thung L, Jackson D, Botella JR, Jones AM. Saltational evolution of the heterotrimeric G protein signaling mechanisms in the plant kingdom. Sci Signal. 2016;9(446):93. 10.1126/scisignal.aaf9558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Y, Assmann SM. Inter-relationships between the heterotrimeric Gβ subunit AGB1, the receptor-like kinase FERONIA, and RALF1 in salinity response. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(10):2475–89. 10.1111/pce.13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang HL, Yu FF, Xie P, Sun SY, Qiao XH, Tang SY, Chen CX, Yang S, Mei C, Yang DK, Wu YR, Xia R, Li X, Lu J, Liu YX, Xie XW, Ma DM, Xu X, Liang ZW, Feng ZH, Huang XH, Yu H, Liu GF, Wang YC, Li JY, Zhang QF, Chang Chen C, Xie Q. A Gγ protein regulates alkaline sensitivity in crops. Science. 2023;379(6638):eade8416. 10.1126/science.ade8416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng L, Qi JM, Cheng SJ, Fang PP. Inheritance Breeding Research of Castor-Oil Plant and its potential utilization in Biological Energy sources and medicament. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2006;(09):109–13.

- 31.Shi ZP, Jiang YT, Chen F. Preliminary study on the current situation and future development of castor cultivation in Ghana. China Seed Ind. 2021;313(4):10–3. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-895X.2021.04.003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y, Lu JF, Zhou GS. Analysis of castor industry in China based on industrial chain perspective. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2011;27(29):124–7. 10.11924/j.issn.1000-6850.2011-0879. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang XY, Li M, Liu XM, Zhang L, Duan Q, Zhang JX. Quantitative proteomic analysis of Castor (Ricinus communis L.) seeds during early imbibition provided novel insights into cold stress response. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(2):355. 10.3390/ijms20020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang BL, Zhou CS, Hai Z, Lou YX. Effects of subsoiling and different irrigation amounts on soil physical and chemical properties and corn yield in Tongliao soda saline-alkali soil. Jiangsu Agricultural Sci. 2024;52(3):247–54. 10.15889/j.issn.1002-1302.2024.03.036. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YN, Jie WG, Peng XY, Hua XY, Yan XF, Zhou ZQ, Lin JX. Physiological adaptive strategies of oil seed crop Ricinus communis early seedlings (Cotyledon vs. True Leaf) under salt and alkali stresses: from the growth, photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence. Front Plant Sci. 2019;9:1939. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohanasundaram B, Pandey S. Moving beyond the Arabidopsis-centric view of G-protein signaling in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2023;28(12):1406–21. 10.1016/j.tplants.2023.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YP, Zhang HL, Wang PX, Zhong H, Liu WZ, Zhang SD, Xiong LM, Wu YY, Xia YJ. Arabidopsis EXTRA-LARGE G PROTEIN 1 (XLG1) functions together with XLG2 and XLG3 in PAMP-triggered MAPK activation and immunity. J Integr Plant Biol. 2023;65(3):825–37. 10.1111/jipb.13391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu R, Li N, Li Y. Control of grain size by G protein signaling in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2019;61(5):533–40. 10.1111/jipb.12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun SY, Wang L, Mao HL, Shao L, Li XH, Xiao JH, OuYang YD, Zhang QF. A G-protein pathway determines grain size in rice. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):851. 10.1038/s41467-018-03141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong XX, Liu Y, Zhang LL, Li XJ, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Yang QH, Yang Y, Min DH, Zhang XH. G-Protein β-Subunit gene TaGB1-B enhances Drought and Salt Resistance in Wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7337. 10.3390/ijms24087337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Zhou YJ, Zhang Y, Hu WG, Wu QH, Chen YX, Wang XC, Guo GH, Liu ZY, Cao TJ, Hong Zhao H. Cloning, characterization of TaGS3 and identification of allelic variation associated with kernel traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). BMC Genet. 2019;20(1):98. 10.1186/s12863-019-0800-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez JC, Williams KL, Appel RD, Hochstrasser DF. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;112:531–52. 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:5312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W585–7. 10.1093/nar/gkm2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CJ, Wu Y, Li JW, Wang X, Zeng ZH, Xu J, Liu YL, Feng JT, Chen H, He YH, Xia R. TBtools-II: a one for all, all for one bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol Plant. 2023;16(11):1733–42. 10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–7. 10.1093/molbev/msab120. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–8. 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang JY, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Lu SN, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yang MZ, Zhang DC, Zheng CJ, Lanczycki CJ, Marchler-Bauer A. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D384–8. 10.1093/nar/gkac10969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P, Rombauts S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–7. 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Gable AL, Fang T, Doncheva NT, Pyysalo S, Bork P, Jensen LJ, Mering C. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D638–46. 10.1093/nar/gkac1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Majeed A, Mukhtar S. Protein-protein Interaction Network Exploration using Cytoscape. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2690:419–27. 10.1007/978-1-0716-3327-4_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown AP, KroonJT, Swarbreck D, Febrer M, Larson TR, Graham LA, Caccamo M, Slabas AR. Tissue-specific whole transcriptome sequencing in castor, directed at understanding triacylglycerol lipid biosynthetic pathways. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e30100. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu C, Sun YG, Fu GR. Advances of salt tolerance mechanism in Hylophyate Plants. Biotechnol Bull. 2013;011–7. 10.13560/j.cnki.biotech.bull.1985.2013.01.026.

- 54.Zhang H, Xie P, Xu X, Xie Q, Yu F. Heterotrimeric G protein signalling in plant biotic and abiotic stress response. Plant Biology (Stuttg). 2021;23(1):20–30. 10.1111/plb.13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang XY, Zhang HY, Liu XM, Meng D, Yuang WP, Huo HY, Yu LL, Zhang JX. Identification of CNGC gene family and analysis of expression pattern under cold stress in castor (Ricinus communis L). Mol Plant Breed. 2021;19:7373–82. 10.13271/j.mpb.019.007373. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei X, Zhang JX, Wang N, Sun MD, Ding X, Xu H, Yu XY, Yue WR, Huo HY, Yu LL, Wang XY. Genome-wide identification and analysis of expression pattern of REVEILLE transcription factors in castor (Ricinus communis L). Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2024. 10.1007/s13580-023-00580-5. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiong ML, Dai X, Jian Y, Li K, Yang ZT. Advances in the study of Abscisic Acid-Dependent and non-dependent signaling pathway. Genomics Appl Biology. 2020;39(12):5796–802. 10.13417/j.gab.039.005796. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grill E, Himmelbach A. ABA signal transduction. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1(5):412–8. 10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Assmann SM, Jegla T. Guard cell sensory systems: recent insights on stomatal responses to light, abscisic acid, and CO2. Current. Opin Plant Biology. 2016;33:157–67. 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Umezawa TS, Nakashima KZ, Miyakawa T, Kuromori T, Tanokura M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Molecular basis of the core regulatory network in ABA responses: sensing, signaling and transport. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(11):1821–39. 10.1093/pcp/pcq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu CY, Hu J, Fan W, Zhu PP, Cao BN, Zheng S, Xia ZQ, Zhu YX, Zhao AC. Heterotrimeric G-protein γ subunits regulate ABA signaling in response to drought through interacting with PP2Cs and SnRK2s in mulberry (Morus alba L). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;161:210–21. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Q, Fu X. Can heterotrimeric G proteins improve sustainable crop production and promote a more sustainable Green Revolution? Innov Life. 2023;1(2):100024. 10.59717/j.xinn-life.2023.100024. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perfus-Barbeoch L, Jones AM, Assmann SM. Plant heterotrimeric G protein function: insights from Arabidopsis and rice mutants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7(6):719–31. 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho Y. Arabidopsis AGB1 participates in salinity response through bZIP17-mediated unfolded protein response. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):586. 10.1186/s12870-024-05296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jangam AP, Pathak RR, Raghuram N, Microarray. Analysis of Rice d1 (RGA1) Mutant Reveals the Potential Role of G-Protein Alpha Subunit in Regulating Multiple Abiotic Stresses Such as Drought, Salinity, Heat, and Cold. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:11. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Yadav DK, Islam SM, Tuteja N. Rice heterotrimeric G-protein gamma subunits (RGG1 and RGG2) are differentially regulated under abiotic stress. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7(7):733–40. 10.4161/psb.20356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma YN, Chen M, Xu DB, Fang GN, Wang EH, Gao SQ, Xu ZS, Li LC, Zhang XH, Min DH, Ma YZ. G-protein β subunit AGB1 positively regulates salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J Integr Agric. 2015;14(2):314–25. 10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60777-2. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Biswas S, Islam MN, Sarker S, Tuteja N, Seraj ZI. Overexpression of heterotrimeric G protein beta subunit gene (OsRGB1) confers both heat and salinity stress tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;144:334–44. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shafi A, Chauhan R, Gill T, Swarnkar MK, Sreenivasulu Y, Kumar S, Kumar N, Shankar R, Ahuja PS, Singh AK. Expression of SOD and APX genes positively regulates secondary cell wall biosynthesis and promotes plant growth and yield in Arabidopsis under salt stress. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;87(6):615–31. 10.1007/s11103-015-0301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–7. 10.1093/molbev/msab120. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and can be found in Supplementary Tables S1, Tables S2, Figure S1, and Figure S2. The RNA-seq data analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under BioProject PRJEB2660 (Accession: ERX021379, ERX021378, ERX021377, ERX021376, ERX021375).