Abstract

Background

Despite widespread use of high-intensity statin monotherapy, achieving target LDL-C levels and reducing cardiovascular events in patients with or at high risk of developing ASCVD remains challenging. Our study measured the effects of low/moderate-intensity statins and ezetimibe combination therapy compared to high-dose statin monotherapy on major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane CENTRAL register of trials for studies comparing the combination therapy to high-intensity statin monotherapy in terms of MACEs and coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death or major cardiovascular events (MI, HF, Revascularization, or non-fatal stroke). Other outcomes included other MACEs, lipid-lowering efficacy, and safety outcomes. A protocol was registered to PROSPERO under registration number [CRD42024545807].

Results

15 studies encompassing 251,450 participants were included in our meta-analysis. In our pooled analysis of observational studies, combination therapy was associated with lower rates of the primary composite outcome (HR = 0.76, CI 95% [0.73, 0.80]), cardiovascular death (HR = 0.80, CI 95% [0.74, 0.88]), all-cause death (HR = 0.84, CI 95% [0.78, 0.91]), and non-fatal stroke (HR = 0.81, CI 95% [0.75, 0.87]). However, the pooled analysis of RCTs did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between both arms concerning clinical endpoints. Combination therapy had a higher number of patients with LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (RR = 1.27, CI 95% [1.21, 1.34]), significantly lowered LDL-C (MD = -7.95, CI 95% [-10.02, -5.89]) and TC (MD = -26.77, CI 95% [-27.64, -25.89]) in the pooled analysis of RCTs. In terms of safety, the combination therapy lowered muscle-related adverse events (RR = 0.52, CI 95% [0.32, 0.85]) and number of patients with liver enzyme elevation (RR = 0.51, CI 95% [0.29, 0.89]) in the pooled analysis of RCTs and was associated with lower rates of new-onset diabetes (HR = 0.80, CI 95% [0.74, 0.87]) in the pooled analysis of observational studies.

Conclusion

Evidence from RCTs indicates that low/moderate statin therapy in combination with ezetimibe has a superior lipid-lowering effect and reduces side effects compared to high-dose statins. Observational studies suggest improved clinical outcomes but need to be corroborated by large, outcomes-powered RCTs over longer follow-up periods.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-024-04144-y.

Keywords: Statins, Ezetimibe, Cardiovascular events, Coronary artery disease, LDL-C

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is believed to be one of the leading risk factors of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [1]. ASCVD, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and peripheral arterial disease, is the number one cause of death and a major burden worldwide; it is of significant concern as the prevalence of ASCVD is rising globally [2, 3].

At present, statin therapy is a cornerstone for coronary heart disease treatment, decreasing blood lipids and preventing further progression of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [4]. International guidelines recommend intensively lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations with statins in patients with established ASCVD to reduce the risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACEs) [5]. Despite the widespread use of high-intensity statin therapy, achieving target LDL-C levels and reducing MACEs remains challenging, and rather than increasing doses of one drug, studies suggest that drug combination can provide higher efficacy with minimal risks [6, 7]. The high risk of dose-dependent adverse effects of statins acts as a barrier to the use of the highest approved statin dose, irrespective of whether adverse events are truly caused by the statin or are perceived to be caused by the statin [8–10].

Ezetimibe, a selective inhibitor of the Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 receptor, effectively inhibits dietary and biliary cholesterol absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, thereby increasing cholesterol clearance from the blood [11]. Co-administration of ezetimibe with low/moderate-intensity statins can reduce LDL-C by 15–22%, making it an alternative pathway to the intensive lipid-lowering approach [12–14]. Although the lipid-lowering effects of combination therapy have already been proven in comparison to high-dose statins [15], effects on clinical outcomes haven’t been well established. Two recent meta-analyses were conducted on combination therapy’s clinical efficacy. The first by Hameed et al. only searched 2 databases, had 3 RCTs, and combined all MACEs into one outcome without drawing any distinctions. The second by Damarpally et al. only included 5 observational studies and assessed 4 outcomes [16, 17]. Accordingly, we sought to provide a more complete assessment of the evidence related to the clinical effects of combination therapy in comparison to high-dose statins.

Methods

Methods and materials

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed according to the Preferred Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [18] and following the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions [19]. A comprehensive protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) [CRD42024545807].

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane CENTRAL register of trials for articles published from Inception till February 20th, 2024. The search was updated on May 17th, 2024 to include any newly published studies. We searched the reference list of all included studies to minimize the chance of missing relevant data. Grey literature and the studies’ authors weren’t sought out due to the inaccessibility of such resources. The Full search is available in the Supplementary Material Appendix 1.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

We included all randomized clinical trials (RCTs), and prospective and retrospective observational studies comparing low/moderate-intensity statins and ezetimibe combination to high-intensity statin monotherapy evaluating cardiovascular outcomes (MACE) and coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction in patients with or at high risk of developing ASCVD (e.g. DM, CKD, Familial Hyperlipidemias, etc.…). All non-English, invitro, animal studies, reviews, editorials, expert opinions, conference abstracts, study protocols, and case reports were excluded. Two independent authors conducted the study screening process and the conflicts were resolved by discussion and a third author opinion.

Data extraction

Two independent authors extracted the data in a standardized Excel sheet, including studies’ characteristics (e.g. author, date, study design), patients’ demographics, baseline characteristics as co-morbidities, previous stroke, medications, lipid profile, and primary and secondary outcomes.

Quality assessment

The quality of the randomized controlled trials was assessed by Cochrane risk of bias (RoB 2) [20], and the quality of the included prospective and retrospective observational studies was assessed by the New-castle Ottawa scale (NOS) [21]. Two independent authors and the conflicts in the assessment were resolved by consensus.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the composite of cardiovascular death or major cardiovascular events (MI, HF, coronary artery revascularization, or non-fatal stroke). Secondary outcomes were the composite of cardiovascular death, or hospitalization for MI or stroke; cardiovascular death; all-cause death; coronary artery revascularization (PCI/Coronary Bypass); acute MI; hospitalization for heart failure; non-fatal stroke (total); ischemic stroke; hemorrhagic stroke; atherosclerotic plaque reduction; lipid parameters; and safety outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Revman software Version 5.4.1. Data from RCTs and observational studies was first divided into two separate meta-analyses to avoid any bias that could arise from observational studies as recommended by the 2023 version of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis [22] and to determine which outcomes have strong supportive evidence from RCTs and which outcomes are primarily based on lower-quality evidence from observational studies. For dichotomous data, risk ratio (RR) was calculated for RCTs using raw counts, and inverse variance-weighted average (IVW) was calculated for observational studies using adjusted hazard ratio with a 95% confidence interval obtained from each study's adjusted analysis for its dichotomous data to account for prognostic and confounding factors capable of influencing the endpoint independently of the intervention or capable of creating spurious associations. For continuous data, the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated for RCTs and observational studies. Statistical significance was indicated by a P-value below 0.05. A random-effects model was used when the chi-square P-value was less than 0.1. Furthermore, a leave-one-out test was performed to identify studies accountable for observed heterogeneity. Assessing publication bias was performed using funnel plotting whenever an outcome had at least 10 studies [23].

Results

Literature search results

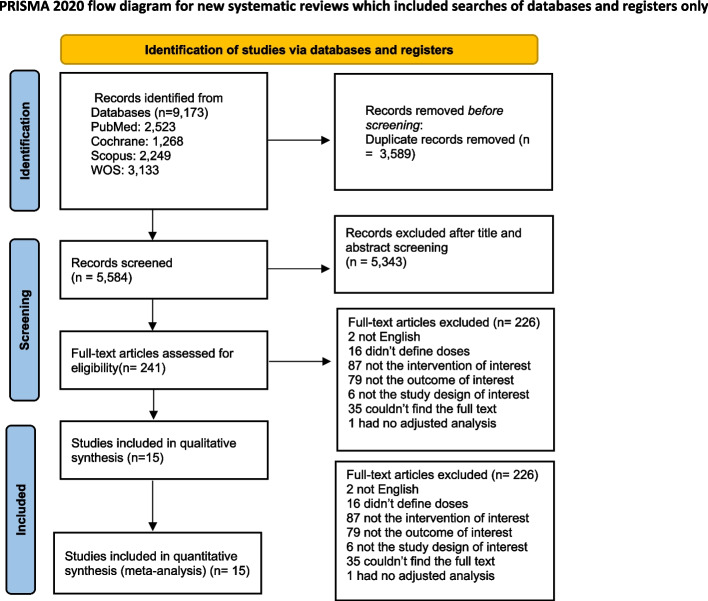

Using our search strategy across different databases yielded a total of 9,173 studies, 3,589 of which were duplicates for automatic exclusion. Subsequent title & abstract screening excluded a further 5,343 studies. The remaining 241 studies that underwent full-text screening were thoroughly assessed, leaving 16 studies to finally be included in our meta-analysis. Of the 15 studies, 6 were RCTs [24–29] and 9 were observational [30–38]. The reasons for exclusion are outlined in the PRISMA flowchart diagram in (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram

Characteristics of included studies

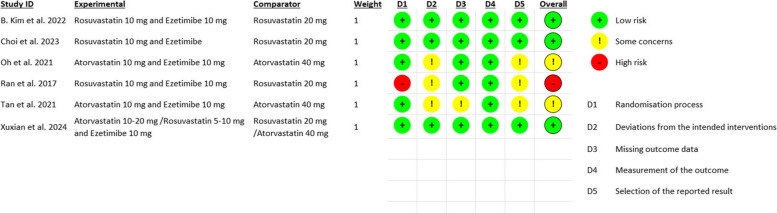

Our meta-analysis included a total of 251,450 participants, 76,280 patients were on the low/moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe arm, while 175,170 patients were on the high-intensity statin monotherapy arm. Approximately 65% of participants were male. 10 studies were conducted in South Korea, 3 in China, and 2 in Taiwan. Details for each included study are summarized in (Table 1), while baseline characteristics are outlined in (Table 2). Utilizing the Cochrane RoB2 tool for assessment of risk of bias in the included RCTs, we remarked a low risk of bias in B. Kim et al. and Choi et al. On the other hand, Oh et al. and Tan et al. raised some concerns due to doubts regarding allocation concealment, outcome data completeness, and blinding of participants and investigators. Ran et al. exhibited a high risk of bias primarily due to inadequacy in their randomization processes. Observational studies were assessed using the NOS tool. All studies attained “Good” quality except for J. Kim et al., which attained “Poor” quality due to inadequate comparability and follow-up of study cohorts. More details regarding quality assessment are in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Comprehensive overview of the included studies

| study ID | Country, site involved | Type of the study | Sample size of each group | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Intervention group drugs and doses | Control group drugs and doses | study duration | conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Kim et al. 2022 [24] | South Korea | RCT |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 1894 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 1886 |

Patients included if they had documented ASCVD requiring high intensity statin therapy and achievement of LDL cholesterol concentrations of less than 70 mg/dL, where documented ASCVD was defined as the presence or occurrence of at least one of the following: previous myocardial infarction (MI), acute coronary syndrome, history of coronary revascularisation or other arterial revascularisation procedures, ischaemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease (PAD) | N/A | rosuvastatin 10 mg with ezetimibe 10 mg once daily orally | rosuvastatin 20 mg once daily orally | 36 months |

"among patients with documented ASCVD, moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy was non-inferior to high-intensity statin monotherapy in terms of a 3-year composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or non-fatal stroke with a higher proportion of patients who achieved LDL cholesterol concentration of less than 70 mg/dL and lower drug discontinuation or dose reduction owing to intolerance" |

| Choi et al. 2023 [25] | Republic of Korea | RCT |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 126 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 132 |

Patients were included if they: 1. Aged between 19 and 75 yr 2. Have an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the form of - Coronary artery disease presented by History of acute coronary syndrome, Stable or unstable angina or History of coronary revascularization -Stroke or TIA - Peripheral arterial disease or history of peripheral arterial revascularization 3. Patients who have been taking lipid-lowering agents (statin or ezetimibe) for ≥ 4 wk at the time of randomization 4. Patients who gave informed consent |

Patients were excluded if they have: 1. used lipid-lowering agents other than statin or ezetimibe within the last 3 months 2. A serum triglyceride level > 400 mg/dL on fasting 3. A history of muscular symptoms or rhabdomyolysis due to the use of statin 4. Hypersensitivity to rosuvastatin or ezetimibe 5. Labelled contraindications to rosuvastatin or ezetimibe including -Severe renal impairment (CrCl < 30 mL/min by Cockcroft-Gault formula or estimated GFR < 30 mL/min /1.73 m2 by MDRD equation) -ALT, AST ≥ 3 × ULN or active liver disease -CPK ≥ 3 × ULN 6. Enrolled in other clinical trials within 30 days 7. Any other issues that the treating physician assumes ineligible for participation in the trial |

fixed-dose single-pill that contained a combination rosuvastatin 10 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg once daily | rosuvastatin 20 mg once daily | 18 months |

"This trial demonstrated that the efficacy of the ezetimibe and moderate-intensity statin combination therapy in lowering LDL-C was better compared to high-intensity statin alone" "both strategies are safe" |

| Chun Oh et al. 2021 [26] | Republic of Korea | RCT |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 18 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 19 |

Patients were included if they: 1. Were aged 19 years or more 2. Had stable angina pectoris with intermediate non-culprit lesions after treatment of culprit lesions with severe stenosis by percutanous coronary angiography, where intermediate non-culprit lesion was defined as a NIRS-IVUS feasible native coronary lesion with 30% to 60% angiographic diameter stenosis and 2.0 mm to 4.0 mm in diameter by visual estimation and located > 10 mm apart from the intervened lesion 3. Had a baseline LDL-C level > 70 mg/dL regardless of the use of previous lipid-lowering agents |

Patients where excluded if they have: 1. Acute coronary syndrome 2. Hemodynamic instability 3. Left ventricular ejection fraction < 35% 4. Estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 5. Serum transaminases levels 3 times greater than the upper normal limit 6. Inadequate lesions for the NIRS-IVUS analysis |

atorvastatin 10 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg daily | atorvastatin 40 mg daily | 26 months |

"the combination of atorvastatin 10 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg showed significant regression of coronary atherosclerosis to a similar degree in the setting of comparable LDL-C reduction, compared with atorvastatin 40 mg alone" |

| J. Kim et al. 2021 [30] | South Korea | Population-based cohort study |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 922 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 19,148 |

Patients were included if they were "18 years of age or older who underwent coronary revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG]) between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2016, and received either moderate-intensity statins plus ezetimibe or high-intensity statins within 1 month after coronary revascularization." |

Patients were excluded if they: 1. Were on hemodialysis 2. Were received treatment for human immunodefciency virus infection 3.Had undergone any organ transplantation 4. Had cardiopulmonary resuscitation at the index revascularization procedure 5.Died during the admission in which the index revascularization was performed 6. Had adverse cardiovascular events after the index revascularization, but before taking statins or ezetimibe |

atorvastatin 10–20 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5–10 mg daily PLUS Ezetimibe 10 mg daily Both in fixed- dose combinations and separate pill combinations |

atorvastatin 40–80 mg or rosuvastatin 20 mg | 24 months |

"the risk of MACE during the 1-year period following a coronary revascularization procedure was similar in patients initially prescribed moderateintensity statins plus ezetimibe and in those prescribed high intensity statins. the data suggests that moderate-intensity statins plus ezetimibe could be an alternative to high-intensity statins for secondary prevention, which may be particularly attractive to patients with statin intolerance" |

| Jang et al. 2024 [31] | Korea | Retrospective cohort |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 15,022 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 143,059 |

Patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention with a diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2019 nationwide were included |

Patients were excluded if they died during hospitalization for PCI |

moderate intensity statins prescribed according to the 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines rosuvastatin 5–10 mg daily, atorvastatin 10–20 mg daily, pravastatin 40 mg daily, Lovastatin 40–80 mg or fluvastatin 80 mg daily PLUS Ezetimibe |

High intensity statins prescribed according to the 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines atorvastatin 40–80 mg daily or rosuvastatin 20 mg daily |

84 months |

"moderate-intensity statin therapy with ezetimibe combination therapy provides a benefit over high-intensity statin monotherapy for the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the patients after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome. These findings support a use of statin and ezetimibe combination therapy for patients with acute coronary syndrome." |

| Jun et al. 2024 [32] | Korea | Retrospective cohort |

(C1) Statins & Ezetimibe = 34,744 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 34,744 |

Adults aged ≥ 20 years with dyslipidemia who underwent national health check-ups and taking high-intensity statin only and those taking moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe (C1) OR taking low-intensity statin and ezetimibe (C2) were included | Patients who had claims for previous myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke, statin users before the index day, ezetimibe users prior to the index day, those who had claims for new MI, stroke, or death whichever came first within 1 year after the index, those who used statins or ezetimibe for < 90 days within 1 year after the index day, and those with missing data for at least one variable at baseline | N/A | N/A | 59 months | “In populations without pre-existing CVD, it might be beneficial to consider moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe combination therapy to prevent the composite of MI, stroke, and overall death, as well as each cardiovascular event, when compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy. Low-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy also demonstrated a similar protective effect on composite outcomes compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy but not on individual outcomes. The effect of combination therapy remained consistent across age groups, sex, and comorbidities. Although these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the several limitations, the combination of statins with ezetimibe may be a viable option for primary CVD prevention and a good alternative to high-intensity statin” |

|

(C2) Statins & Ezetimibe = 6527 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 6527 | |||||||||

| K. Kim et al. 2021 [33] | South Korea | Retrospective cohort |

[A] Statins & Ezetimibe = 233 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 4,041 |

"patients with MI who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for the first time between January 2013 and December 2016 using the KNHIS database." were included |

"patients Excluded if: 1. Age < 20 years 2. Missing health examination within 2 yearscof index PCI 3. History of AF or thromboembolism 4. History of cancer 5. History of stroke 6. Follow-up period < 1 year 7. Other statins were prescribed 8. Missing data" |

Atorvastatin 20 mg + Ezetimibe 10 mg daily | Atorvastatin 40 mg daily | 48 months |

"There was no significant difference in the composite outcome of MACE between high-intensity statin monotherapy and moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe combination therapy." |

|

[R] Statins & Ezetimibe = 383 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 5,251 |

Rosuvastatin 10 mg + Ezetimibe 10 mg daily | Rosuvastatin 20 mg daily | |||||||

| Kao et al. 2021 [34] | Taiwan | Retrospective cohort |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 1686 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 1686 |

Patients with T2DM aged ≥ 40 years who were admitted due to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or acute ischemic stroke (AIS) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2013 | Patients aged < 40 years, expired during index hospitalization, developed primary outcome within 30 days, follow up less than 30 days, not prescribed any statins within 30 days], prescribed other statins witnin 30 days, prescribed 2 kinds of study drug at the time window | Ezetimibe 10 mg/ simvastatin 20 mg | Atorvastatin 40 mg | 84 months | "In summary, our results of study supported the concept that LDL-C is a key role in the pathogenesis of ASCVD and the capacity of medication to lower of LDL-C regardless of statin or non-statin therapies (ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors) is defnitely the frst concern rather than the pleiotropic efects." |

| Lee et al. 2023 [A] [35] | Korea | Retrospective cohort |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 6215 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 25,778 |

Adult patients (≥ 20 years old) who underwent DES implantation between January 2005 and December 2015 (CONNECT DES cohort registry), dose of atorvastatin was used as the primary inclusion criterion in this study: atorvastatin 20 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg for the combination lipid-lowering therapy and atorvastatin 40–80 mg for high-intensity statin monotherapy | Patients with chronic liver disease, solid organ transplant recipients, people who were or might become pregnant, patients treated with statins other than atorvastatin, those who did not meet the statin intensity criteria specified in the RACING trial, patients who did not receive any statin treatment after their PCI, patients who died within 7 days of PCI or had missing covariate data were excluded from the study | Ezetimibe 10 mg/ atorvastatin 20 mg | Atorvastatin 40–80 mg | 35 months | "In this nationwide cohort study, the combination of moderateintensity atorvastatin and ezetimibe was associated with a lower occurrence of adverse cardiovascular events, statin discontinuation, and the emergence of new-onset diabetes requiring medication than high-intensity atorvastatin monotherapy in patients who had undergone PCI with DES implantation. The current real-world data support the suitability of upfront combination lipid-lowering therapy as a primary treatment strategy in patients at high risk of ASCVD." |

| Lee et al. 2023 [R] [36] | Korea | Retrospective cohort |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 10,794 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 61,256 |

Patients with ASCVD who had undergone PCI and received either combination lipidlowering therapy (rosuvastatin 10 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg daily) or high-intensity statin monotherapy (rosuvastatin 20 mg daily) between January 2016 and December 2018 |

Patients with chronic liver disease, solid organ transplant recipients, and pregnant or potential child-bearing women. patients who received statins other than rosuvastatin, a rosuvastatin dosage different from the RACING trial, and those without a statin prescription were not included in this study. Patients who died within 7 days after PCI or with missing covariates were also excluded from the study |

Ezetimibe 10 mg/ rosuvastatin 10 mg | Rosuvastatin 20 mg | 35 months | "In this nationwide cohort study, combination lipidlowering therapy with moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe was associated with a lower occurrence of adverse cardiovascular events, statin discontinuation, and diagnosis of new-onset diabetes requiring medication than high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients who underwent PCI with DES implantation. These results not only strengthen the generalizability of the randomized RACING trial in clinical practice but also provide new insight into the efficacy and safety of combination lipid-lowering therapy." |

| Liu et al. 2016 [37] | Taiwan | Retrospective cohort |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 564 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 1510 |

Patients with type 2 DM in the NHIRD with the main diagnoses of IS or transient ischemic attack for hospitalization | Patients without a definite cerebral infarction were excluded. The young-stroke population and patients with renal replacement therapy were also excluded due to limited statin prescription | Ezetimibe 10 mg/ simvastatin 20 mg | Atorvastatin 40 mg | 34 months | "This study shows that both the ATOR and EZ-SIM provide better secondary IS prevention than SIM alone for diabetic IS patients without increased incidence of HS. High-potency LLT is helpful for reducing the recurrence of IS in DM patients, regardless of whether ATOR alone or EZ-SIM combination therapy is used." |

| Ran et al. 2017 [27] | China | RCT |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 42 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 41 |

Patients who were at least 18 years old and had been hospitalized within the preceding 10 days for non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (including unstable angina and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction) at the second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from July 2015 to June 2016 | Patients who received lipid-lowering therapy within six months; severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class IIIb or IV and left ventricular ejection fraction < 30%); alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≥ 3ULN; renal insufficiency (serum creatinine > 176 mmol/L (2.0 mg/dL)); unexplained elevated creatine kinase (CK) ≥ 1ULN; current use of medication that may interact with statins and/or ezetimibe; history of statin-induced myopathy or serious hypersensitivity to statins or ezetimibe | Ezetimibe 10 mg/ rosuvastatin 10 mg | rosuvastatin 20 mg | 34 months | "The present findings suggest that compared with rosuvastatin 20 mg and 10 mg, the combination of ezetimibe 10 mg/rosuvastatin 10 mg is much more effective in lowering lipid level and caused lower incidences of drug-related adverse events in Chinese patients with NSTE-ACS." |

| Seon Ji et al. 2016 [38] | Korea | Registry study |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 1249 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 2271 |

Between November 2005 and January 2014, Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and were treated with simvastatin–ezetimibe or high-intensity statin therapy during administration or upon discharge were selected. high-intensity statin therapy was defined as atorvastatin 40–80 mg daily or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg daily according to guidelines | Use of moderate-intenstity statins or low-intensity statins. Concomitant use of statins or simvastatin-ezetimibe. No use of simvastatin-ezetimibe nor statins | Ezetimibe (No available dose)/ simvastatin (No available dose) | Atorvastatin 40–80 mg OR Rosuvastatin 20–40 mg | 98 months | "In overall AMI patients, high-intensity statin had better clinical outcomes than simvastatin–ezetimibe. However, in specific high-risk AMI patients, simvastatin-ezetimibe had comparable clinical outcomes to high-intensity statin. Therefore, we suggest simvastatin–ezetimibe could be an effective alternative therapy to high-intensity statin in specific subgroups of patients." |

| Tan et al. 2021 [28] | China | RCT |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 91 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 92 |

Patients who: (1) had chest pain that occurred frequently and had lasted for a long time in the past month and had experienced a persistent attack of chest pain for 15 min on the day before; (2) had glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c%) < 6.5%, but with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or impaired fasting blood glucose (IFG); had undergone an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to determine whether the patient was diabetic after the patient was stabilized at a later stage; (3) during the onset of chest pain, the ST segment of the two connected leads was elevated or depressed ≥ 0.1 mV (chest leads ≥ 0.2 mV); (4) had no increase of creatine kinase (CK), creatine kinase MB (CKMB), troponin (Tn) and other myocardial enzyme markers; (5) had new wall motion abnormalities (perforation of interventricular septum, rupture of papillary muscle, ventricular aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm) found on echocardiography or a radionuclide myocardial perfusion defect (myocardial ischemia or myocardial infarction); (6) male or female patients aged 18–75 years | Patients who were allergic to the study drugs; (3) patients currently taking drugs such as immunosuppressants or drugs combined with statins, which may increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis, or taking bette, nicotinic acids and other lipid-lowering drugs; (4) patients with obstructive anthrax, active liver disease and chronic hepatitis; (5) patients with severe hepatic and renal insufficiency(dyspepsia, loss of appetite, ascites, edema, abnormal urine output and weight loss caused by detoxification or metabolic function); (6) patients with myopathy (progressive myasthenia gravis and muscular atrophy); (7) patients with cardiomyopathy or New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV or heart failure with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40%; (8) patients with positive pregnancy test or childbearing and lactating women who did not take contraceptive measures; (9) patients with malignant tumor, rheumatic connective tissue and other immune systemic diseases; (11) patients with a life expectancy < 24 months | Ezetimibe 10 mg/ atorvastatin 10 mg | Atorvastatin 40 mg | 17 months | "Based on the overall results of this study, the lipid-lowering effect of atorvastatin combined with ezetimibe in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome elicited a superior effect than that of atorvastatin alone, with a low incidence of cardiovascular adverse events. It provides a theoretical basis for and insight into clinical treatment of acute coronary syndrome. More studies with larger sample sizes are warranted for further confirmation." |

| Xuxian Lv et al. 22,024 [29] | China | RCT |

Statins & Ezetimibe = 69 High-intensity Statin monotherapy = 65 |

Patients diagnosed with acute ischemic cerebrovascular disease, aged 18 years or older, within the acute phase of ischemic stroke, i. e., within 1 week after the onset of mild ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤ 5), within 1 month for severe cases (NIHSS score ≥ 16), and within 2 weeks for the rest, as well as patients with TIA within 1 week of symptom onset were included | Pregnant or lactating women, individuals suspected of having cardioembolic TIA or stroke, suspected cases of intracranial hemorrhage, patients with liver or kidney dysfunction, those with baseline serum creatine kinase levels ≥ 5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), and patients who had used medications known to affect lipid levels within the past month or probucol within the past 6 months were excluded |

Ezetimibe 10 mg/ atorvastatin 10–20 mg OR Rosuvastatin 5–10 mg |

Atorvastatin 40 mg OR Rosuvastatin 20 mg |

3 months | "Compared to guideline-recommended high-intensity statin therapy, moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe further improved the achievement rate of LDL-C in patients with acute ischemic cerebrovascular disease, with a higher reduction magnitude in LDL-C. In terms of safety, there was no significant difference." |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients in each included study

| Study ID | ARMS | Number of Patients | Age (years) | Male | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | Current smoker | Comorbidities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyslipidemia | Hypertension | Diabetes | Heart Failure | Acure Myocardial Infarction | Unstable Angina | STEMI | NSTEMI | Previous Myocardial Infarction | percutaneous coronary intervention | ||||||||

| mean ± SD | n (%) | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| B. Kim et al. 2022 [24] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 1894 | 64 ± 10 | 1420 (75) | 68 ± 11 | 25∙0 ± 3∙2 | 328 (17) | N/A | 1246 (66) | 701 (37) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 744 (39) | 1258 (66) |

| Statin Monotherapy | 1886 | 64 ± 10 | 1406 (75) | 68 ± 11 | 25∙1 ± 3∙1 | 310 (16) | N/A | 1246 (66) | 697 (37) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 745 (40) | 1239 (66) | |

| Choi et al. 2023 [25] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 126 | 63.5, [39.0, 75.0] | 91 (72.2) | 68.8, [46.0, 95.7] | N/A | 26 (20.6) | N/A | 63 (50.0) | 40 (31.8) | N/A | 27 (21.4) | 46 (36.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 132 | 63.5, [25.0, 74.0] | 104 (78.8) | 70.8, [44.0, 121.1] | N/A | 30 (22.7) | N/A | 69 (52.3) | 44 (33.3) | N/A | 18 (13.6) | 36 (27.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Chun Oh et al. 2021 [26] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 18 | 56.3 ± 7.1 | 13 (72) | N/A | 25.0 ± 2.1 | 5 (28) | 8 (44) | 10 (56) | 6 (33) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 19 | 56.7 ± 8.4 | 15 (79) | N/A | 24.4 ± 3.1 | 5 (26) | 9 (47) | 10 (53) | 5 (26) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| J. Kim et al. 2021 [30] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 922 | 65 (57–73) Median (IQR) | 604 (65.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 681 (73.9) | 487 (52.8) | 171 (18.5) | 226 (24.5) | 388 (42.1) | N/A | N/A | 85 (9.2) | 904 (98.0) |

| Statin Monotherapy | 19,148 | 63 (55–73) Median (IQR) | 14,254 (74.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12,859 (67.2) | 8622 (45.0) | 3400 (17.8) | 9294 (48.5) | 4994 (26.1) | N/A | N/A | 2165 (11.3) | 18,687 (97.6) | |

| Jang et al. 2024 [31] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 10,723 | (≤ 40 s 1015 (9.5%)) (50 s 2489 (23.2%)) (60 s 3307 (30.8%)) (70 s 2714 (25.3%)) (≥ 80 s 1198 (11.2%)) | 7544 (70.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9245 (86.2) | 3546 (33.1) | 1788 (16.7) | N/A | 4563 (42.6) | 1828 (17.0) | 3076 (28.7%) | 3967 (37.0) | 507 (4.7) |

| Statin Monotherapy | 10,723 | (≤ 40 s 994 (9.3%)) (50 s 2459 (22.9%)) (60 s 3311 (30.9%)) (70 s 2734 (25.5%)) (≥ 80 s 1225 (11.4%)) | 7590 (70.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9305 (86.8) | 3516 (32.8) | 1737 (16.2) | N/A | 4538 (42.3) | 1851 (17.3) | 3089 (28.8%) | 3962 (37.0) | 459 (4.3) | |

| Jun et al. 2024 (C1) [32] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 34,744 | 57.1 ± 9.8 | 17,177 (49.4) | N/A | 25.3 ± 3.3 | 6321 (18.2) | N/A | 19,438 (56.0) | 10,365 (29.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 34,744 | 57.0 ± 9.8 | 16,962 (48.8) | N/A | 25.3 ± 3.4 | 6151 (17.7) | N/A | 19,283 (55.5) | 10,315 (29.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Jun et al. 2024 (C2) [32] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 6527 | 56.6 ± 10.0 | 3175 (48.6) | N/A | 24.9 ± 3.2 | 1149 (17.6) | N/A | 2855 (43.7) | 1665 (25.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 6527 | 56.7 ± 10.1 | 3161 (48.4) | N/A | 24.9 ± 3.2 | 1148 (17.6 | N/A | 2839 (43.5) | 1610 (24.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| K. Kim et al. 2021 [33] | Statins And Ezetimibe [A] | 233 | 59.1 ± 11.0 | 190 (81.6) | N/A | 25.2 ± 3.5 | 110 (47.2) | N/A | 208 (89.3) | 80 (34.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 48 (20.6) | 88 (37.8%) | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy [A] | 4041 | 59.8 ± 10.9 | 3,397 (84.1) | N/A | 25.0 ± 3.1 | 1,822 (45.1) | N/A | 3,611 (89.4) | 1,264 (31.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 953 (23.6) | 1,221 (30.2%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Statins And Ezetimibe [R] | 383 | 59.0 ± 10.8 | 319 (83.3) | N/A | 24.7 ± 3.0 | 186 (48.6) | N/A | 338 (88.3) | 108 (28.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 68 (17.8) | 132 (34.5%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Statin Monotherapy [R] | 5251 | 59.3 ± 11.2 | 4,404 (83.9) | N/A | 25.0 ± 3.1 | 2,373 (45.2) | N/A | 4,740 (90.3) | 1,574 (30.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 956 (18.2) | 1,599 (30.5%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Kao et al. 2021 [34] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 1686 | N/A | 885 (52.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1254 (74.4) | 1480 (87.8) | 1686 (100) | 197 (11.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 136 (8.1) | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 1686 | N/A | 861 (51.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1241 (73.6) | 1461 (86.7) | 1686 (100) | 210 (12.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 133 (7.9) | N/A | |

| Lee et al. 2023 [A] [35] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 6215 | 62.8 ± 11.0 | 4657 (74.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4508 (72.5) | 2845 (45.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 25,778 | 62.7 ± 11.2 | 19,382 (75.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18 717 (72.6) | 11 534 (44.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Lee et al. 2023 [R] [36] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 10,794 | 62.3 ± 10.9 | 7867 (72.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8242 (76.4) | 5007 (46.4) | N/A | 2584 (23.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2360 (21.9) | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 61,256 | 62.8 ± 11.5 | 44,729 (73) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 46,246 (75.5) | 27,215 (44.4) | N/A | 16,680 (27.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13,500 (22.0) | N/A | |

| Liu et al. 2016 [37] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 564 | 65.4 ± 10.9 | 312 (55.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 478 (84.8) | 564 (100) | 26 (4.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15 (2.7) | 4 (0.7) |

| Statin Monotherapy | 1510 | 66.2 ± 11.0 | 838 (55.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1283 (85.0) | 1510 (100) | 102 (6.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 27 (1.8) | 16 (1.1) | |

| Ran et al. 2017 [27] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 42 | 60.4 ± 8.2 | 32 (76.2) | N/A | 22.786 ± 1.774 | 23 (54.8) | N/A | 21 (50.0) | 11 (26.2) | N/A | N/A | 28 (66.7) | N/A | 14 (33.3) | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 41 | 60.5 ± 10.0 | 30 (73.2) | N/A | 22.741 ± 1.682 | 22 (53.7) | N/A | 20 (48.8) | 11 (26.8) | N/A | N/A | 29 (70.7) | N/A | 12 (29.3) | N/A | N/A | |

| Seon Ji et al. 2016 [38] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 1249 | 61.2 ± 13.19 | 945 (76.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 132 (12.1) | 589 (47.7) | 357 (28.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 799 (64.0) | 450 (36.0) | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 2271 | 61.3 ± 12.90 | 1778 (78.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 281 (12.8) | 1036 (46.3) | 690 (30.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1347 (59.3) | 924 (40.7) | N/A | N/A | |

| Tan et al. 2021 [28] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 91 | 49.83 ± 9.87 | 51 (56.04) | N/A | 26.19 ± 2.39 | 39 (42.86) | N/A | 21 (23.08) | 65 (71.43) | N/A | 27 (29.67) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 21 (23.08) | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 92 | 48.08 ± 9.01 | 50 (54.35) | N/A | 26.03 ± 3.01 | 37 (40.22) | N/A | 17 (18.48) | 63 (68.48) | N/A | 26 (28.26) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19 (20.65) | N/A | |

| Xuxian Lv et al. 2024 [29] | Statins And Ezetimibe | 69 | 62.07 ± 10.79 | 48 (69.57) | N/A | 24.67 [22.5, 26.9] | 21 (30.43) | N/A | 40 (57.97) | 15 (21.74) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Statin Monotherapy | 65 | 60.77 ± 12.96 | 37 (56.92) | N/A | 23.55 [22.0, 25.4] | 17 (26.15) | N/A | 32 (49.23) | 13 (20.00) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Study ID | Comorbidities | Previous stroke | Medications | Laboratory finding | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous coronary bypass graft surgery | Chronic kidney disease | End-stage kidney disease on dialysis | Peripheral artery disease | Cancer/malignancy | Any | Ischemic | Aspirin | Clopidogrel | Beta-blocker | ACE inhibitor | ARB | ACE/ARB | Calcium channel blocker | P2Y12 blocker | LDL (mg/dL) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | mean ± SD | |

| B. Kim et al. 2022 [24] | 132 (7) | 193 (10) | 13 (1) | 66 (4) | N/A | N/A | 101 (5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 80 (64—100) median (IQR) |

| 115 (6) | 199 (11) | 16 (1) | 69 (4) | N/A | N/A | 112 (6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 80 (64—100) median (IQR) | |

| Choi et al. 2023 [25] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 79.5 (32—209) median (IQR) |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 78.5 (34—192) median (IQR) | |

| Chun Oh et al. 2021 [26] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18 (100) | 18 (100) | 8 (44) | 3 (17) | 5 (28) | N/A | 8 (44) | N/A | 107.0 ± 31.5 |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19 (100) | 19 (100) | 12 (63) | 5 (26) | 5 (26) | N/A | 9 (47) | N/A | 100.6 ± 30.7 | |

| J. Kim et al. 2021 [30] | 18 (2.0) | 47 (5.1) | N/A | 307 (33.3) | 95 (10.3) | 81 (8.8) | N/A | 874 (94.8) | N/A | 572 (62.0) | N/A | N/A | 470 (51.0) | N/A | 809 (87.7) | N/A |

| 461 (2.4) | 696 (3.6) | N/A | 4854 (25.3) | 1640 (8.6) | 2075 (10.8) | N/A | 18,898 (98.7) | N/A | 14,837 (77.5) | N/A | N/A | 13,759 (71.9) | N/A | 18,330 (95.7) | N/A | |

| Jang et al. 2024 [31] | 521 (4.9) | N/A | 270 (2.5) | 891 (8.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1255 (11.7) | N/A |

| 462 (4.3) | N/A | 167 (1.6) | 829 (7.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1245 (11.6) | N/A | |

| Jun et al. 2024 (C1) [32] | N/A | 2377 (6.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7117 (20.5) | N/A | 2778 (8.0) | 403 (1.2) | 15,099 (43.5) | N/A | 10,753 (31.0) | 2302 (6.6) | 126.5 ± 50.3 |

| N/A | 2255 (6.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9784 (28.2) | N/A | 3909 (11.3) | 1200 (3.5) | 13,488 (38.8) | N/A | 9168 (26.4) | 5144 (14.8) | 125.9 ± 54.9 | |

| Jun et al. 2024 (C2) [32] | N/A | 415 (6.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1102 (16.9) | N/A | 409 (6.3) | 94 (1.4) | 1990 (30.5) | N/A | 1467 (22.5) | 371 (5.7) | 146.7 ± 42.7 |

| N/A | 411 (6.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1520 (23.3) | N/A | 562 (8.6) | 176 (2.7) | 1977 (30.3) | N/A | 1384 (21.2) | 877 (13.4) | 146.7 ± 52.3 | |

| K. Kim et al. 2021 [33] | 2 (0.9%) | N/A | 3 (1.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 196 (84.1) | 93 (39.9) | 113 (48.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 138.0 ± 45.9 |

| 23 (0.6) | N/A | 19 (0.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3,600 (89.1) | 1,956 (48.4) | 1,819 (45.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 132.5 ± 39.3 | |

| 3 (0.8) | N/A | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 309 (80.7) | 148 (38.6) | 189 (49.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 134.6 ± 39.4 | |

| 19 (0.4) | N/A | 16 (0.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4,595 (87.5) | 2,069 (39.4) | 2,616 (49.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 133.1 ± 42.9 | |

| Kao et al. 2021 [34] | N/A | N/A | 71 (4.2) | 99 (5.9) | 96 (5.7) | N/A | 328 (19.5) | 1506 (89.3) | 746 (44.2) | 785 (46.6) | N/A | N/A | 1220 (72.4) | 875 (51.9) | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | 71 (4.2) | 90 (5.3) | 93 (5.5) | N/A | 328 (19.5) | 1532 (90.9) | 739 (43.8) | 776 (46.0) | N/A | N/A | 1230 (73.0) | 885 (52.5) | N/A | N/A | |

| Lee et al. 2023 [A] [35] | 101 (1.6) | N/A | N/A | 350 (5.6) | N/A | N/A | 1108 (17.8) | 4288 (69.0) | 3172 (51.0) | 3023 (48.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 362 (1.4) | N/A | N/A | 1414 (5.5) | N/A | N/A | 4413 (17.1) | 16 669 (64.7) | 12 767 (49.5) | 11 827 (45.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Lee et al. 2023 [R] [36] | 119 (1.1) | N/A | N/A | 625 (5.8) | N/A | N/A | 1747 (16.2) | 7049 (65.3) | 5247 (48.6) | 4579 (42.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 632 (1.0) | N/A | N/A | 3332 (5.4) | N/A | N/A | 9552 (15.6) | 37,845 (61.8) | 28,565 (46.6) | 25,251 (41.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Liu et al. 2016 [37] | N/A | 15 (2.7) | N/A | 46 (8.2) | 23 (4.1) | 130 (23.0) | 104 (18.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | 40 (2.6) | N/A | 84 (5.6) | 68 (4.5) | 344 (22.8) | 254 (16.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Ran et al. 2017 [27] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5 (11.9) | N/A | 41 (97.6) | 37 (88.1) | 39 (92.9) | N/A | N/A | 29 (69.0) | N/A | N/A | 141 ± 27 |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 (7.3) | N/A | 40 (97.6) | 36 (87.8) | 36 (87.8) | N/A | N/A | 29 (70.7) | N/A | N/A | 141 ± 35 | |

| Seon Ji et al. 2016 [38] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1248 (99.9) | 1173 (93.9) | 1115 (92.0) | N/A | N/A | 1056 (87.3) | N/A | N/A | 125.2 ± 38.56 |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2268 (99.9) | 2090 (92.3) | 2060 (97.6) | N/A | N/A | 1951 (95.0) | N/A | N/A | 121.9 ± 39.80 | |

| Tan et al. 2021 [28] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Xuxian Lv et al. 2024 [29] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13 (18.84%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.12 ± 0.96 |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 (9.23%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.26 ± 0.98 | |

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment of RCTs

MACE outcomes

Primary composite outcome

In the pooled analysis including observational studies, combination therapy was associated with lower rates of the primary composite outcome (HR = 0.76, CI 95% [0.73, 0.80], P < 0.01) Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.13, I2 = 56%) (Fig. 3A) There was no adequate RCT evidence with respect to this outcome.

Fig. 3.

A Forest plot of observational studies showing the primary composite outcome (composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular event (MI, HF, Revascularization), or non-fatal stroke). B Forrest plot of observational studies illustrating composite of cardiovascular death, or hospitalization for MI or Stroke

Composite of cardiovascular death, or hospitalization for MI or Stroke

In a pooled analysis of observational studies, there was no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy at reducing the composite rates of cardiovascular death, or hospitalization for MI or Stroke (HR = 1.06, CI 95% [0.94, 1.19], P = 0.33). Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.73, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3B). There wasn’t enough evidence from RCTs to perform a pooled analysis for this outcome.

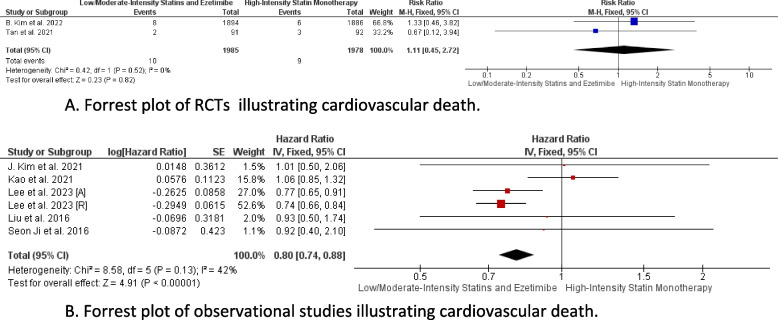

Cardiovascular death

In the pooled analysis of RCTs, there was no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing cardiovascular death rates (RR = 1.11, CI 95% [0.45, 2.72], P = 0.82), with heterogeneity being low (P = 0.52, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4A). However, the pooled analysis including observational studies demonstrated a strong association between combination therapy and cardiovascular death reduction (HR = 0.80, CI 95% [0.74, 0.88], P < 0.01), with low heterogeneity (P = 0.13, I2 = 42%) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A Forrest plot of RCTs illustrating cardiovascular death. B Forrest plot of observational studies illustrating cardiovascular death

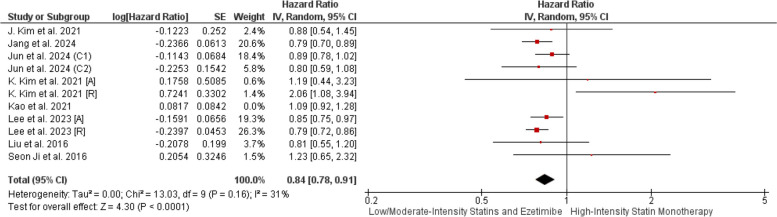

All-cause death

Our pooled analysis of observational studies demonstrated a strong association between combination therapy and all-cause death reduction (HR = 0.84, CI 95% [0.78, 0.91], P < 0.01). Heterogeneity was initially high (P = 0.01, I2 = 55%), but resolved after excluding Kao et al. (P = 0.16, I2 = 31%) (Fig. 5, Supplementary File Fig. 1).

Fig. 5.

Forrest plot of observational studies demonstrating All-cause death POST-LOT

Acute MI

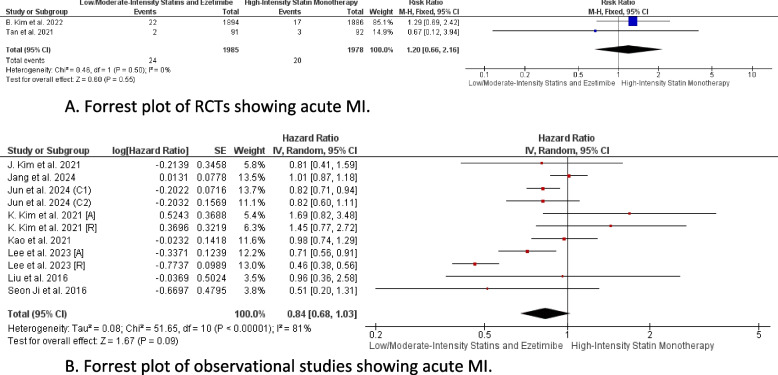

In the pooled analysis including RCTs, there was no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing MI rates (RR = 1.20, CI 95% [0.66, 2.16], P = 0.55), with heterogeneity being low (P = 0.50, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 6A) Similarly, the pooled analysis including observational studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in MI reduction (HR = 0.84, CI 95% [0.68, 1.03], P = 0.09), with heterogeneity being high (P < 0.01, I2 = 81%) (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

A Forrest plot of RCTs showing acute MI. B Forrest plot of observational studies showing acute MI

Coronary Artery Revascularization (CAR)

In the pooled analysis including RCTs, there was no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing CAR rates (RR = 1.01, CI 95% [0.76, 1.33], P = 0.96), with heterogeneity being low (P = 0.70, I2 = 0%). Similarly, the pooled analysis including observational studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in CAR reduction (HR = 0.98, CI 95% [0.71, 1.36], P = 0.92), with heterogeneity being high (P < 0.01, I2 = 86%). (Supplementary File Fig. 2, 3).

Hospitalization for heart failure

In the pooled analysis including RCTs, there was no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing hospitalizations for heart failure (RR = 0.76, CI 95% [0.40, 1.44], P = 0.40), with heterogeneity being low (P = 0.78, I2 = 0%). Similarly, the pooled analysis including observational studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing hospitalizations for heart failure (HR = 0.94, CI 95% [0.87, 1.01], P = 0.10), with heterogeneity also being low (P = 0.46, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 4, 5).

Non-fatal Stroke (total)

Our pooled analysis of observational studies demonstrated a strong association between combination therapy and non-fatal stroke reduction (HR = 0.81, CI 95% [0.75, 0.87], P < 0.01). Heterogeneity was initially high (P = 0.02, I2 = 61%), but resolved after excluding Kao et al. (P = 0.66, I2 = 0%) (Supplementary File Fig. 6A, 6B). There was insufficient evidence from RCTs to perform a pooled analysis for this outcome.

Ischemic stroke

In the pooled analysis including RCTs, there was no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing ischemic stroke rates (RR = 0.84, CI 95% [0.39, 1.84], P = 0.67), with heterogeneity being low (P = 0.29, I2 = 9%). Similarly, the pooled analysis including observational studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the combination therapy and monotherapy in ischemic stroke reduction (HR = 1.26, CI 95% [0.92, 1.73], P = 0.15), with heterogeneity also being low (P = 0.21, I2 = 35%). (Supplementary File Fig. 7, 8).

Hemorrhagic stroke

Our pooled analysis of observational studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing rates of hemorrhagic stroke (HR = 0.64, CI 95% [0.35, 1.16], P = 0.14). Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.34, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 9) There was insufficient evidence from RCTs to perform a pooled analysis for this outcome.

Lipid parameters

No. of patients with LDL-C cholesterol concentrations < 70 mg/dL

In our pooled analysis of RCTs, the combination therapy arm had a statistically significantly higher number of participants with LDL-C cholesterol concentrations < 70 mg/dL compared with monotherapy (RR = 1.27, CI 95% [1.21, 1.34], P < 0.01). Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.35, I2 = 8%). (Supplementary File Fig. 10).

Other lipid parameters

In our pooled analysis of RCTs, there was a statistically significant change in LDL-C levels favoring the combination therapy (MD = -7.95, CI 95% [-10.02, -5.89], P < 0.01). Heterogeneity was initially high (P < 0.01, I2 = 88%), but resolved after excluding Choi et al. (P = 0.68, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 11A, 11B) However, our pooled analysis of observational studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between combination therapy and monotherapy in LDL-C reduction (MD = -3.12, CI 95% [-12.23, 5.99], P = 0.50), with heterogeneity being high (P < 0.01, I2 = 98%) (Supplementary File Fig. 12). In another pooled analysis of RCTs, the combination therapy showed a statistically significant change in TC levels (MD = -26.77, CI 95% [-27.64, -25.89], P < 0.01). Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.11, I2 = 54%). (Supplementary File Fig. 13) Regarding other parameters, pooled analyses of RCTs revealed no statistically significant difference between both therapies concerning changes in HDL-C (MD = 6.42, CI 95% [-8.37, 21.20], P = 0.40) (Supplementary File Fig. 14) and TGs (MD = -5.69, CI 95% [-26.25, 14.87], P = 0.59) (Supplementary File Fig. 15) along with high heterogeneity in the first outcome (P < 0.01, I2 = 98%) and low heterogeneity in the second (P = 0.68, I2 = 0%), respectively.

Safety outcomes

Musculoskeletal

Our pooled analysis of RCTs revealed a statistically significant reduction in muscle-related adverse events favoring the combination therapy (RR = 0.52, CI 95% [0.32, 0.85], P < 0.01) along with low heterogeneity (P = 0.75, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 16) However, no reduction was seen specifically in rhabdomyolysis events in the pooled RCT analysis (RR = 0.74, CI 95% [0.35, 1.59], P = 0.44) or pooled observational study analysis (HR = 0.83, CI 95% [0.62, 1.09], P = 0.18) along with low heterogeneity in both analyses [(P = 0.38, I2 = 0%), (P = 0.86, I2 = 0%)], respectively. (Supplementary File Fig. 17, 18) A pooled analysis of RCTs also demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the number of patients with CK elevation (RR = 0.71, CI 95% [0.47, 1.08], P = 0.11), with low heterogeneity (P = 0.85, I2 = 0%) (Supplementary File Fig. 19).

Hepatobiliary

Regarding Liver enzyme elevation, our pooled analysis of RCTs revealed a statistically significant reduction in the number of patients with liver enzyme elevation favoring the combination therapy (RR = 0.51, CI 95% [0.29, 0.89], P = 0.02) along with low heterogeneity (P = 0.49, I2 = 0%) (Supplementary File Fig. 20). As for GI symptoms, our pooled analysis of RCTs showed no reduction in GI symptoms events (RR = 0.56, CI 95% [0.22, 1.47], P = 0.24), with low heterogeneity (P = 0.55, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 21) A pooled analysis of observational studies for gallbladder-related adverse events was also done to reveal no reduction in its events (HR = 1.11, CI 95% [0.94, 1.30], P = 0.22) along with low heterogeneity (P = 0.23, I2 = 29%) (Supplementary File Fig. 22).

New-onset diabetes

In our pooled analysis of observational studies, the combination therapy was strongly associated with reduced events of new-onset diabetes with anti-diabetic medication initiation (HR = 0.80, CI 95% [0.74, 0.87], P < 0.01), with heterogeneity being low (P = 0.92, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 23) There was insufficient evidence from RCTs to perform a pooled analysis for this outcome.

Cancer diagnosis

In our pooled analysis of observational studies, there was no statistically significant difference between combination therapy and monotherapy in reducing cancer diagnosis events (HR = 0.99, CI 95% [0.91, 1.07], P = 0.76). Heterogeneity was low among pooled studies (P = 0.78, I2 = 0%). (Supplementary File Fig. 24) There was insufficient evidence from RCTs to perform a pooled analysis for this outcome.

Coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction

Due to insufficient studies, we only conducted a narrative review. In Chun Oh et al., the combination therapy and high-intensity statin monotherapy had nearly similar effects on coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction in patients with stable angina. The primary endpoint of the study was percent atheroma volume (PAV), which was reduced from baseline by 2.9% and 3.2% in the combination arm and monotherapy arm, respectively (MD = 0.5%, CI 95% [-2.4%, 2.8%] P = 0.285). The Lipid Core Burden Index (LCBI) was another outcome calculated by quantifying the amount of lipid core in the atherosclerotic plaque. LCBI wasn’t significantly reduced in both groups at follow-up, with only 44% and 63% of patients experiencing any reduction in LCBI in the combination and monotherapy arms, respectively. However, LCBI reduction was strongly associated with reduced LDL-C, apolipoprotein B, and hs-CRP [25].

Discussion

Summary of findings

Our meta-analysis found that although observational studies suggest that this combination therapy offers significant cardiovascular benefits compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy such as reducing the primary composite outcome, cardiovascular death, all-cause death, and non-fatal stroke events, there is a paucity of evidence from RCTs to corroborate such findings due to the limited number of studies, small sample sizes and short follow-up periods. However, the greater reductions seen in LDL-C by combination therapy are supported by RCTs. Therefore, they may provide indirect evidence that combination therapy can lead to a greater reduction in MACE. However, we stress that further corroboration of this in dedicated RCTs is needed.

Regarding lipid parameters, participants receiving combination therapy were more likely to achieve LDL-C concentrations below 70 mg/dL, a commonly recommended threshold for reducing cardiovascular risk. Moreover, combination therapy significantly reduced LDL-C and TC levels compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy. However, it did not have a significant impact on HDL-C and TG levels.

Safety-wise, combination therapy led to fewer muscle-related adverse events and lowered the incidence of liver enzyme elevations, both findings supported by RCTs. It was associated with a lower incidence of new-onset diabetes compared to high-intensity statin monotherapy in observational studies. On the other hand, there was also no notable reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms, gallbladder-related adverse events, or cancer diagnosis. All results are summarized in (Table 3) for reference.

Table 3.

Outcomes

| Outcome | Analysis group | No. of included studies | Point estimate (95%CI) | Heterogeneity | Which drug the outcome favours | Figure No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Composite Outcome (Composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular event (MI, HF, Revascularization), or non-fatal stroke) | Observational studies | 2 | HR 0.76 (0.73, 0.80) | 56% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | 3A |

| Composite of cardiovascular death, or hospitalization for MI or Stroke | Observational studies | 3 | HR 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) | 0% | No difference between two arms | 3B |

| Cardiovascular Death | RCTs | 2 | RR 1.11 (0.45, 2.72) | 0% | No difference between two arms | 4A |

| Observational studies | 6 | HR 0.80 (0.74, 0.88) | 42% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | 4B | |

| All-cause Death | Observational studies | 10 | HR 0.84 (0.78, 0.91) | 31% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | 5 |

| Acute MI | RCTs | 2 | RR 1.20 (0.66, 2.16) | 0% | No difference between two arms | 6A |

| Observational studies | 11 | HR 0.84 (0.68, 1.03) | 81% | No difference between two arms | 6B | |

| Coronary Artery Revascularization | RCTs | 2 | RR 1.01 (0.76, 1.33) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 2 |

| Observational studies | 6 | HR 0.98 (0.71, 1.36) | 86% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 3 | |

| Hospitalization for Heart Failure | RCTs | 2 | RR 0.76 (0.40, 1.44) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 4 |

| Observational studies | 3 | HR 0.94 (0.87, 1.01) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 5 | |

| Non-fatal Stroke (total) | Observational studies | 6 | HR 0.81 (0.75, 0.87) | 0% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 6A |

| Ischemic Stroke | RCTs | 2 | RR 0.84 (0.39, 1.84) | 9% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 7 |

| Observational studies | 3 | HR 1.26 (0.92, 1.73) | 35% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 8 | |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | Observational studies | 2 | HR 0.64 (0.35, 1.16) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 9 |

| No. of patients with LDL cholesterol concentrations 70 mg/dL at the end of the study | RCTs | 4 | RR 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) | 8% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 10 |

| Reduction of LDL-C from baseline at the end of the study | RCTs | 2 |

MD -7.95 (-10.02, -5.89) |

0% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 11A |

| Observational studies | 2 |

MD -3.12 (-12.23, 5.99) |

0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 12 | |

| Change in TC from baseline at the end of the study | RCTs | 3 |

MD -26.77 (-27.64, -25.89) |

54% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 13 |

| Change in HDL-C from baseline at the end of the study | RCTs | 3 | MD 6.24 (-8.37, 21.20) | 98% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 14 |

| Change in TG from baseline at the end of the study | RCTs | 2 | MD -5.69 (-26.25, 14.87) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 15 |

| Muscle-related Adverse Events | RCTs | 5 | RR 0.52 (0.32, 0.85) | 0% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 16 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | RCTs | 2 | RR 0.74 (0.35, 1.59) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 17 |

| Observational studies | 3 | HR 0.83 (0.62, 1.09) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 18 | |

| No. of Patients with CK elevation | RCTs | 3 | RR 0.71 (0.47, 1.08) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 19 |

| No. of Patients with Liver Enzymes elevation | RCTs | 3 | RR 0.51 (0.29, 0.89) | 0% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 20 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | RCTs | 3 | RR 0.56 (0.22, 1.47) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 21 |

| Gallbladder-related Adverse Events | Observational studies | 2 | HR 1.11 (0.94, 1.30) | 29% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 22 |

| New-onset diabetes with anti-diabetic medication initiation | Observational studies | 2 | HR 0.80 (0.74, 0.87) | 0% | Low/Moderate-intensity Statins and Ezetimibe | Supplementary Fig. 23 |

| Cancer Diagnosis | Observational studies | 4 | HR 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0% | No difference between two arms | Supplementary Fig. 24 |

HR Hazard Ratio, RR Risk Ratio, MD Mean Difference

Explanation of findings

To our knowledge, our meta-analysis is the first to thoroughly investigate the clinical efficacy of low/moderate intensity statins and ezetimibe combination versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in terms of MACEs in patients with or at high risk of developing ASCVD. Concerning lipid-lowering efficacy and incidence of muscle-related and liver enzyme adverse events, estimates from RCTs favored combination therapy. Concerning clinical outcomes, estimates from observational studies were generally more positive and favored combination therapy. In contrast, estimates from RCTs were imprecise and did not demonstrate evidence of benefit favoring combination therapy. This may be due to the limited number of studies, small sample sizes, and short follow-up periods of the included RCTs. An example to validate such a claim is the RACING trial, which had a sufficient sample size and follow-up period to demonstrate the non-inferiority of combination therapy in reducing adverse cardiovascular events [24]. Other RCTs similar to the RACING trial are needed to give us a full picture of the combination therapy’s clinical potential instead of relying on data from observational studies that can carry a high risk of bias in their data.

Two recent meta-analyses were conducted on combination therapy’s clinical efficacy. The first by Hameed et al. only searched 2 databases and had 3 RCTs to use in their pooled analysis of MACEs. They also combined the total incidence rate of all events for both arms without drawing distinctions between them [16]. This reduces the granularity of the analysis and its clinical utility. The second by Damarpally et al. only included 5 observational studies. They found that combination therapy is associated with reducing all-cause death events but not MI and CAR events, which is similar to our findings. However, their data showed no association with reducing non-fatal stroke events, which differed from our findings [17]. The notable lipid-lowering effects of the combination therapy are already well-established in studies [39]. And since reducing LDL-C is linked to better clinical outcomes [40, 41], it’s reasonable to hypothesize that the combination therapy would prove superior to high-intensity statin monotherapy at reducing cardiovascular events. In support of such a hypothesis, our findings indicate the potential of combination therapy to reduce cardiovascular events.

Another recent meta-analysis conducted in 2022 showed that the combination of low/moderate intensity statins and ezetimibe had greater effects on lipid parameters than high-intensity statin monotherapy [39]. Although our study’s main objective differed, our meta-analysis aligns with these findings as more participants achieved LDL-C concentrations < 70 mg/dL in the combination arm. Reduction of LDL-C is associated with better clinical outcomes, with statins recommended as the cornerstone therapy [40, 41]. Moreover, since ASCVD patients carry a very high risk of cardiovascular disease, guidelines recommend an LDL-C concentration goal of < 70 mg/dL or a more intensive goal of < 55 mg/dL [40, 41]. These goals can prove hard to achieve by merely increasing the dose of statins due to the increased risk of potential side effects and consequently adherence to therapy [42, 43].

A study involving Medicare beneficiaries revealed that only 58.9% of patients hospitalized for MI adhered to high-intensity statin monotherapy at 6 months, and only 41.6% at 2 years post-discharge [44]. On the other hand, J. Kim et al. and the RACING trial found that adherence to low/moderate-intensity statins plus ezetimibe therapy was higher, likely due to the lower risk of side effects seen with high-intensity statin doses [30]. Our findings align with previous studies as participants in the combination arm were less likely to experience muscle-related adverse events and liver enzyme elevation in RCTs, or new-onset diabetes in observational studies.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, due to a lack of larger RCTs with longer follow-up periods similar to the RACING trial, our data heavily relied on results from observational studies. While observational studies attempted to mitigate bias by adjusting for clinically relevant confounders, confounding and bias of results remain major issues in such studies and are essentially unavoidable as some confounders may be not at all measured, imperfectly measured, or unknown. As such, residual confounding is an important concern for data derived from observational studies and means our presented data must be interpreted with caution until more proof regarding clinical outcome effectiveness can be established. Thus, there remains a need for larger clinical trials with longer follow-up periods remains to precisely illustrate the clinical differences between the two approaches to lipid-lowering treatment. Secondly, some included RCTs demonstrated some concerns with respect to bias. Thirdly, we couldn’t properly assess coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction in our study due to insufficient studies for a pooled analysis. Another limitation in our study is the inclusion of studies written in the English language only. In addition, some outcomes such as acute myocardial infarction and revascularization displayed a high degree of heterogeneity. This may be due to variations in the interventions (different doses and degrees of adherence to medications), and outcome definition (e.g., use of different troponin assays and different clinical decision-making concerning revascularization). Moreover, we couldn’t find enough studies to perform a pooled analysis of coronary atherosclerotic plaque reduction, limiting our ability to fulfill one of our main objectives and further highlighting the need for more clinical trials assessing combination therapy’s efficacy. Lastly, all included studies were conducted in Asian countries, which may limit generalization to other populations.

Conclusion

Because of superior lipid-lowering effects and fewer side effects, the combination of low/moderate-intensity statins and ezetimibe illustrates promising potential to reduce cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. Although our data should be interpreted cautiously, our findings set the stage for combination therapy as a valid and potentially preferable option for patients who cannot tolerate high-intensity statins or require additional LDL-C lowering to reach target levels. Further research is warranted with larger clinical trials in different countries to corroborate this therapeutic strategy's long-term cardiovascular benefits (or lack thereof) and safety across larger populations over longer follow-up periods.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

P.S. led the team, overseeing the search strategy's development and execution, ensuring idea validity, and addressing conflicts during screening and quality evaluation. B.Q. carried out the analysis and handled the results section and tables. M.S. engaged in screening and data extraction. M.T.O. assisted in quality assessment and wrote the introduction section. N.N. and N.A. contributed to screening and quality assessment. N.S. contributed to screening and writing the methods section. M.O. and H.S. contributed to data extraction. K.F.M. assisted in idea development and wrote the discussion section. A.S. supervised and conducted a thorough peer review. All authors actively participated in the manuscript review, collectively endorsing the final version.

Funding

All author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or the data repositories listed in References.

Data availability

Data and analysis are provided within the manuscript and supplementary file.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pirillo A, Casula M, Olmastroni E, Norata GD, Catapano AL. Global epidemiology of dyslipidaemias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(10):689–700. [cited 2024 May 29].Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41569-021-00541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–210 http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673617321529/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Lundqvist CB, Borger MA, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–619. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel PN, Giugliano RP. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering therapy for the secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2020;2020(3). [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7868100/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ballantyne CM, Blazing MA, King TR, Brady WE, Palmisano J. Efficacy and safety of ezetimibe co-administered with simvastatin compared with atorvastatin in adults with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(12):1487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387–97. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Bégaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients - The PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):403–14. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: 10.1007/s10557-005-5686-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preiss D, Seshasai SRK, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, et al. Risk of Incident Diabetes With Intensive-Dose Compared With Moderate-Dose Statin Therapy: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2556–64. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/646699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Björnsson ES. Hepatotoxicity of statins and other lipid-lowering agents. Liver International. 2017;37(2):173–8. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: 10.1111/liv.13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson MH. Ezetimibe: a novel option for lowering cholesterol. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2003;1(1):11–21. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1586/14779072.1.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudhop T, Lütjohann D, Kodal A, Igel M, Tribble DL, Shah S, et al. Inhibition of Intestinal Cholesterol Absorption by Ezetimibe in Humans. Circulation. 2002;106(15):1943–8. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034044.95911.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phan BAP, Dayspring TD, Toth PP. Ezetimibe therapy: Mechanism of action and clinical update. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;8(1):415–27. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=dvhr20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kashani A, Sallam T, Bheemreddy S, Mann DL, Wang Y, Foody JAM. Review of side-effect profile of combination ezetimibe and statin therapy in randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(11):1606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ah YM, Jeong M, Choi HD. Comparative safety and efficacy of low- or moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy and high-intensity statin monotherapy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0264437. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/articleid=10.1371/journal.pone.0264437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hameed I, Shah SA, Aijaz A, Mushahid H, Farhan SH, Dada M, et al. Comparative Safety and Efficacy of Low/Moderate-Intensity Statin plus Ezetimibe Combination Therapy vs. High-Intensity Statin Monotherapy in Patients with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2024;24(3):419–31. [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40256-024-00642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damarpally N, Sinha T, Nunez MM, Guntha M, Soe TM, Chaudhari SS, et al. Comparison of Effectiveness of High Dose Statin Monotherapy With Combination of Statin and Ezetimibe to Prevent Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(3). [cited 2024 May 29]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11004506/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Second Edition. 2019 [cited 2024 Jun 14]; Available from: http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

- 20.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/366/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Wells G, Shea B, Robertson J, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis.

- 22.Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Shea B, Tugwell P, Wells GA. Chapter 24: Including non-randomized studies on intervention effects. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 23.Holger J Schünemann GEVJPHNSJJDPGEAAGHG. Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions | Cochrane Training. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-15.