Abstract

Introduction

Homeless populations face higher barriers to health care access. A student-led patient navigation program (PNP) was established pairing groups of trained medical students, who serve as patient navigators, together with an individual experiencing homelessness (IEH) to develop goals tailored to each IEH’s needs. The purpose of this study was to collect data pertaining to the goals of IEH centered on the social determinants of health (SDH) domains.

Methods

IEH were invited to voluntarily participate in the program and patient navigators met with IEH weekly for a 12-week period to guide and connect patients with resources to accomplish the patients’ goals. Manual review of each IEH’s goals was performed and categorized according to SDH domains and further categorized into subdomains using qualitative content analysis.

Results

A total of 86 goals were categorized for 19 participants, with an average of 4.5 goals per IEH. The most common goals were related to “economic stability” (n=34), followed by “health care access” (n=25), “neighborhood and built environment” (n=11), “social and community context” (n=10), and lastly “education access” (n=6). The most common goals based on subcategories were related to “housing” (n=13) and “employment and career development” (n=10).

Conclusion

“Economic stability” and “health care access-related” goals were the most common among IEH participants. Subcategorization analyses revealed that “obtaining identification documentation (ID)” was a common goal that did not easily fit into the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC)-defined categories but provided insight into necessary services. Characterizing the goals of IEH permits the development of targeted resources to assist IEH and bridge health care accessibility gaps.

Introduction

Individuals experiencing homelessness (IEH) encounter greater systemic barriers to health care access and face higher rates of morbidity and mortality.1 Health and homelessness are intertwined, as IEH must often prioritize attaining basic needs, such as food and shelter, over health care.2–5

IEH are a diverse population with heterogeneous needs, and consideration of their specific needs is necessary to promote health care in IEH.6 Patient navigation is a community-based intervention designed to minimize barriers to health care access by providing target populations social assistance and resources to obtain health care.7,8

A student-led patient navigation program (PNP) was created at the University of Texas at Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) in 2020. Medical students voluntarily enroll in a 6-month training program to learn about resources to improve the health and well-being of IEH.9 The PNP program partners with a local homeless shelter to pair groups of three to four students, who serve as patient navigators, with an IEH for a period of 12 weeks.

While the literature on goals of IEH in the context of PNP remains scarce, the importance of working collaboratively with IEH to provide support and develop individualized care plans are common themes amongst studies.10–12 Patient navigators work with IEH to establish a set of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals related to any aspects of their lives of which they may need assistance.13 Defining the parameters of the goals with this method ensures that IEH’s objectives are attainable within the cycle time frame. SMART goals range from health care-related goals (eg, applying for health care financial assistance or setting up a primary care appointment) to other social-service related goals (eg, obtaining affordable housing or employment, applying for identification cards, accessing reliable transportation). Patient navigators and IEH work together on a weekly basis for a period of 12 weeks to develop goals tailored to each IEH’s needs, and patient navigators connect IEHs to community resources specific to each IEH’s goals.

The purpose of this study was to collect data pertaining to the goals of IEH centered on the social determinants of health (SDH) domains. A better understanding of the IEH’s needs permits the development of more targeted resources to assist IEH and educates students regarding common goals of IEH.

Methods

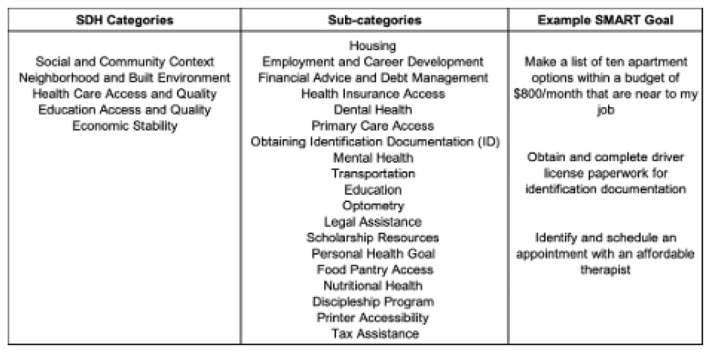

The UTSW Human Institutional Review Board approved this study. All IEH at a single women’s homeless shelter were invited to voluntarily participate in the student-led patient navigator program, and qualitative content analysis of IEH goals from all patient navigation clients in 2021 was performed.14 No compensation was offered for participation. Medical student navigation teams recorded SMART goals on a template document in a SharePoint (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) database. We performed manual review of documents to extract data on each IEH goals by a student reviewer. Two student reviewers who have completed a patient navigator curriculum and are familiar with SDH analyzed goals by categorizing them into the Center of Disease Control and Prevention(CDC)-defined SDH categories. A third reviewer was available to resolve any discrepancies.15,16 Goals were further subcategorized by quantifying the frequencies of specific goal topics per student review (Figure 1). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism 7 (Dotmatics, San Diego, CA) were used to analyze results.

Figure 1.

List of Social Determinants of Health Categories, Subcategories and Example SMART Goals

Abbreviation: SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound

Results

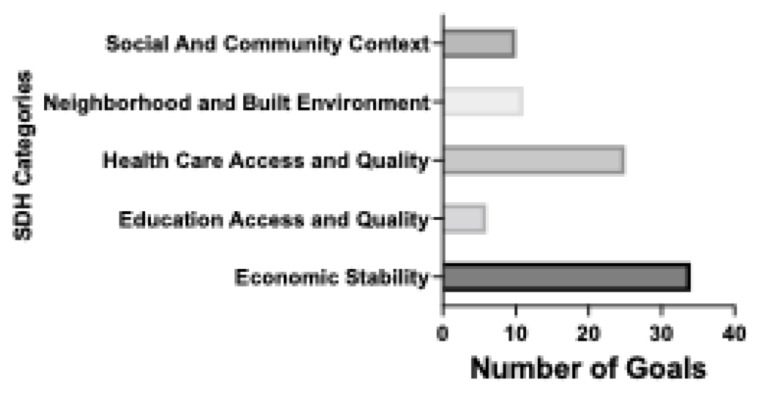

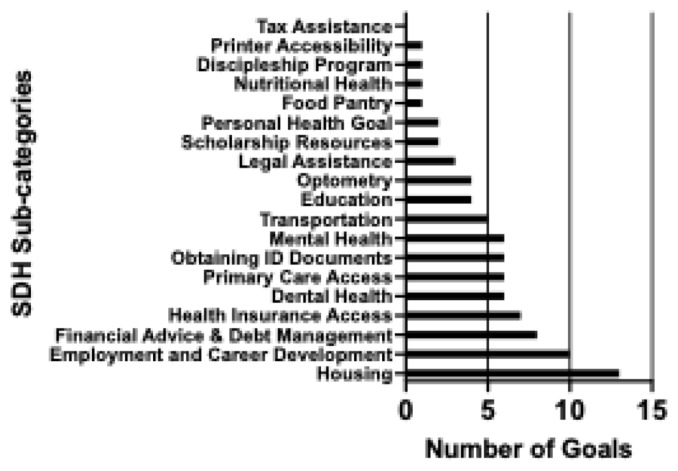

All IEH participating were female and the average age of participants was 47.3 years. A total of 86 SMART goals were categorized for 19 IEH, with an average of 4.5 goals set per IEH. The most common SMART goals were related to “economic stability” (n=34), followed by “health care access and quality” (n=25), “neighborhood and built environment” (n=11), “social and community context” (n=10), and lastly “education access and quality” (n=6; Figure 2). SMART goals were also subcategorized to highlight the nuances in IEHs’ goals. The most common goals based on subcategories were related to “housing” (n=13) and “employment and career development” (n=10), followed by “financial advice and debt management” (n=8), and “health insurance access” (n=7). The least common subcategory was “tax assistance” (n=0), followed by “food pantry,” “nutritional health,” “discipleship program,” and “printer resources” (n=1; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Characterization of Most Common Goals Experienced by Individuals Experiencing Homelessness Based on CDC-Defined Social Determinants of Health Categories

Abbreviations: SDH, social determinants of health; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Figure 3.

Characterization of Most Common Goals Experienced by Individuals Experiencing Homelessness Based on Social Determinants of Health Subcategories

Abbreviations: SDH, social determinants of health

Conclusion

We found that “economic stability” and “health care access-related” goals were the most common among IEHs enrolled in our patient navigator program. Given that IEH may only reside in the shelter system for a limited period, “obtaining housing” was found to be the most common goal. Thus, resource development should be directed towards assisting IEH with finding safe and affordable housing. Our PNP program has a resources team that maintains a database of resources for low-income housing, free and reduced-cost healthcare, and transportation resources. Continuously expanding the resources within this database enables the expansion of services for IEH.

While SDH categories as defined by CDC provide helpful generalizations regarding IEH’s goals, they do not always capture the full picture.17 Nuances in goals, which were difficult to characterize under the broader CDC-defined SDH categories, or belong in more than one SDH category, underscore the importance of examining subcategories. In one IEH’s case, a primary goal was to schedule an appointment with mental health services/counseling. While this could be categorized within the ‘healthcare access and quality’ SDH domain, knowing the specific sub-category is useful for the Patient Navigator team to allocate resources specific to mental health. The importance of sub-categories is further underscored by goals that did not fit easily within the broader SDH categories. “Obtaining identification (ID) documentation” was a surprisingly common goal that did not easily fit into the broader SDH domains but provided important insight into necessary services, as ID documentation is often necessary for healthcare access and obtaining employment.18

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size. Participants all identified as women and were receiving services from the same homeless shelter in a single city in Texas, which may reduce the generalizability of the results. Intentions for future studies include implementing focus groups, administering surveys assessing IEH feedback, and longitudinal assessment collecting information such as average length of stay in the shelter system and which SMART goals were successfully accomplished. Overall, these findings provide valuable insight for the development of more targeted resources to assist IEH and enhance medical student education regarding common goals of IEH. More broadly, our findings may be informative to other student-led patient navigator programs.

References

- 1. Omerov P, Craftman ÅG, Mattsson E, Klarare A. Homeless persons’ experiences of health- and social care: A systematic integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bax A, Middleton J. Healthcare for people experiencing homelessness. BMJ. 2019;364:l1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):241–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh A, Daniel L, Baker E, Bentley R. Housing Disadvantage and Poor Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(2):262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Power R, French R, Connelly J, et al. Health, health promotion, and homelessness. BMJ. 1999;318(7183):590–592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ustjanauskas AE, Bredice M, Nuhaily S, Kath L, Wells KJ. Training in Patient Navigation: A Review of the Research Literature. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(3):373–381. doi: 10.1177/1524839915616362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ranaghan C, Boyle K, Meehan M, Moustapha S, Fraser P, Concert C. Effectiveness of a patient navigator on patient satisfaction in adult patients in an ambulatory care setting: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Reports. 2016;14(8):172–218. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Annapureddy D, Teaw S, Kumar P, et al. Assessing Educational and Attitudinal Outcomes of a Student Learner Experience Focused on Homelessness. Fam Med. 2023 doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2023.112960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sarango M, de Groot A, Hirschi M, Umeh CA, Rajabiun S. The Role of Patient Navigators in Building a Medical Home for Multiply Diagnosed HIV-Positive Homeless Populations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(3):276–282. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shearer AJ, Hilmes CL, Boyd MN. Community Linkage Through Navigation to Reduce Hospital Utilization Among Super Utilizer Patients: A Case Study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2019;78(6 suppl 1):98–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gruenewald DA, Doan D, Poppe A, Jones J, Hutt E. “Meet Me Where I Am”: Removing Barriers to End-of-Life Care for Homeless Veterans and Veterans Without Stable Housing. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(12):1483–1489. doi: 10.1177/1049909118784008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doran GT. There’sa SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manage Rev. 1981;70(11):35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forman J, Damschroder L. Qualitative content analysis. Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2007. pp. 39–62. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health WCoSDo. Organization WH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health final report. World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prevention OoD, Promotion H. HealthyPeople.gov. Social Determinants of Health; Apr, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frank J, Abel T, Campostrini S, Cook S, Lin VK, McQueen DV. The Social Determinants of Health: time to Re-Think? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5856. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Slockers MT, van Hintum M, van Valderen-Antonissen R. [Healthcare for the homeless] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2021 Jul 16;:165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]