Abstract

Maternal Mortality Review Committees are one of the methods employed to measure and address the problem of pregnancy-related death. Reviewing Missouri cases from 2017–2020, 79% of the cases where failure to screen or provide an adequate risk assessment by a health care provider were identified in a pregnancy-related death were determined to be preventable. Recommendations for improvement most commonly addressed issues with assessment of mental health conditions, substance use disorder (SUD), intimate partner violence (IPV), and cardiovascular disease. Although limited, these findings indicate an opportunity for providers to lower the state of Missouri’s pregnancy-related mortality ratio.

Introduction

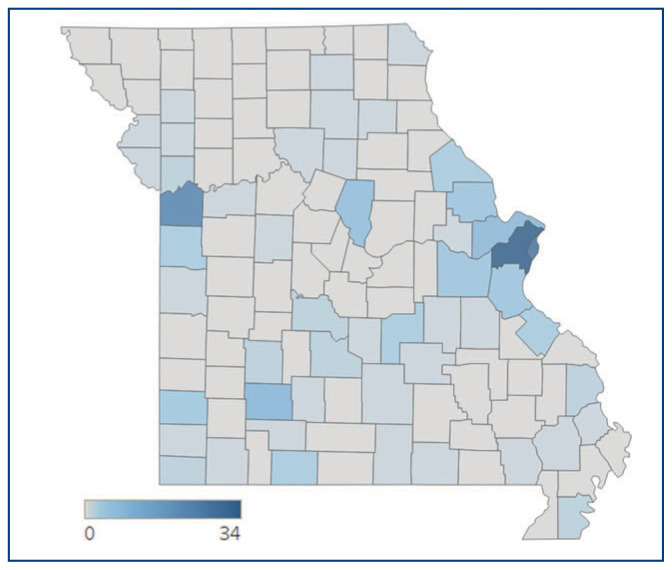

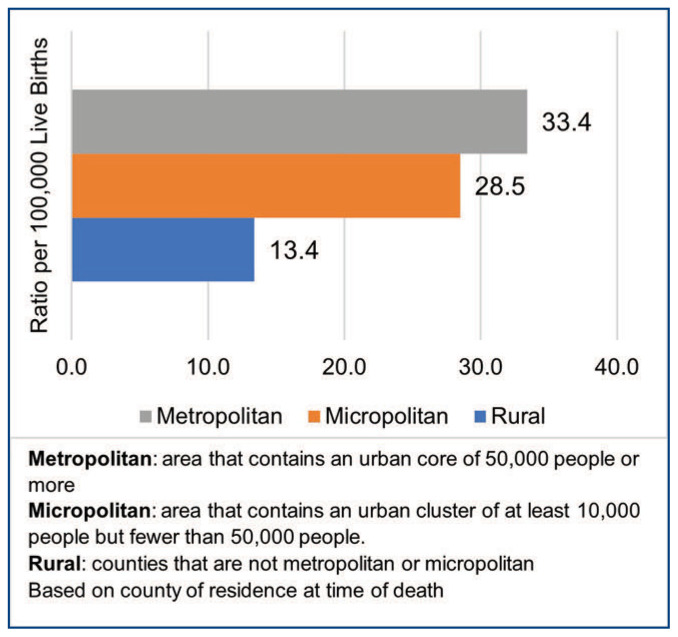

In the United States, 1,205 women died of maternal causes in 2021. Comparatively, there were 861 such deaths in 2020 and 754 in 2019.1 On average, there are roughly 70 women who die during or within one year of pregnancy in Missouri. Pregnancy-associated deaths were spread across the state of Missouri (Figure 1). However, as shown in Figure 2, pregnancy-related deaths have the highest ratio among metropolitan residents. Additionally, every year, roughly 60,000 women had a serious complication or severe maternal morbidity event,2 while Missouri averages 956 severe maternal morbidity events annually. To address the underlying issues contributing to these adverse outcomes, the Missouri Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review (PAMR) board, the state’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee, has completed reviews of maternal deaths from 2017–2020.3

Figure 1.

Count of Pregnancy-Associated Deaths by County, Missouri 2017–2020

Figure 2.

Ratio of Pregnancy-Related Death by Residential Area

Methodology

The board reviews all cases of pregnancy-associated death when a Missouri resident dies while pregnant, during delivery, or within one year postpartum, regardless of the cause. Cases are identified using the pregnancy checkbox from the death certificate, ICD-10 coding indicating pregnancy, and a birth-death linkage, which matches death certificates to birth certificates and fetal death reports. After identification, the PAMR nurse abstractor requests medical records, autopsy reports, and police records when applicable. The abstractor merges these records with social media histories and other data to create a de-identified case summary that is then presented to the board. Using the most complete data obtainable, the board then evaluates each case and determines if it is pregnancy-related.4 A pregnancy-related death is defined as a death attributable to a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiological effects of pregnancy. The board’s determinations and other findings are recorded using a standardized committee decisions form5 generated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Appendix A) and used in reports to provide data-driven guidance to those working to end maternal mortality.

Several distinctions exist between the PAMR process and other maternal mortality surveillance systems. For example, the committee can review and disagree with the cause of death listed on the death certificate.6 Perhaps chief among these systemic differences is that the board seeks to determine if a death was preventable, meaning that after reviewing the circumstances surrounding a death, they found that there was at least some chance one or more reasonable changes could have prevented the death. The board then makes recommendations to ensure similar situations may have a different outcome in the future. These recommendations address specific factors that contributed to a death, such as delays in treatment, violence, and lack of knowledge.

Analysis

After aggregating data from 2017–2020 reviews, one contributing factor emerged as the most common factor that could have altered the outcome if addressed. For pregnancy-related deaths, the most commonly identified contributing factor was assessment (Table 1). Assessment was identified as a contributing factor when the board determined that failure to screen or inadequate screening of risk factors placed the pregnant individual at increased risk for a poor clinical outcome, and/or they were not transferred to receive timely, appropriate care.

Table 1.

Percentage of Contributing Factors for Pregnancy-Related Deaths

| Factor | Percentage | Factor | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | 13.2 | Clinical Skill | 4.3 |

| Mental Health Conditions | 9.8 | Delay | 4.0 |

| Knowledge | 9.2 | Chronic Disease | 3.7 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 8.3 | Referral | 3.7 |

| Other | 7.0 | Discrimination | 3.4 |

| Access/Financial | 6.7 | Social Support | 3.4 |

| Adherence | 5.8 | Policies/Procedures | 3.1 |

| Continuity of Care | 5.8 | Unstable Housing | 2.5 |

| Violence | 4.6 | Communication | 1.8 |

The majority (79%) of pregnancy-related deaths where the board determined that inadequate provider assessment occurred were determined to be preventable. A provider is defined as an individual with training, expertise, certification, and licensure to provide care, treatment, and/or medical advice.

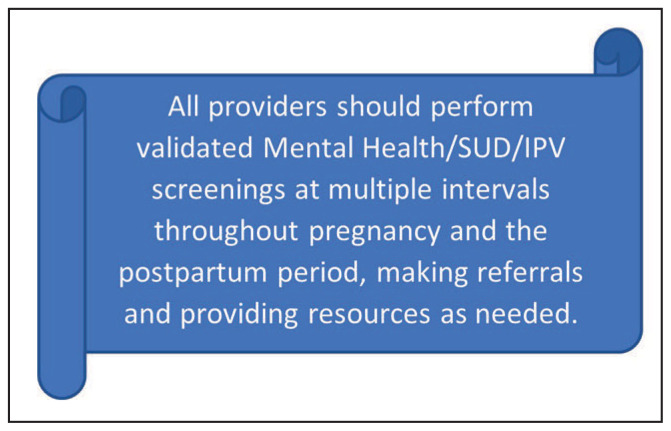

Instances where the board determined that assessment was a contributing factor were linked, on a case-by-case basis, to recommendations to improve health outcomes. These recommendations most commonly resembled Figure 3. While the majority (88%) of recommendations for enhanced assessment occurred at the provider level, hospital or health system-level changes would also result in enhanced assessment. Improved systematic assessment through screening can result in early intervention, potentially reducing the impact of major complications, and decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality.

Figure 3.

Leading Recommendation When Contributing Factor is Assessment.

Further, 12% of assessment recommendations were explicitly directed at facility or health system improvements. Often, these recommendations focused on utilizing standard practices and procedures using evidence-based programs such as the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM), which provides the adoption of patient safety bundles—specifically those that will improve the identification and treatment of issues in the perinatal period. The majority of these recommendations were specific to the AIM bundles: Care for Pregnant and Postpartum People with Substance Use Disorder, Severe Hypertension in Pregnancy, and Cardiac Conditions in Obstetric Care.

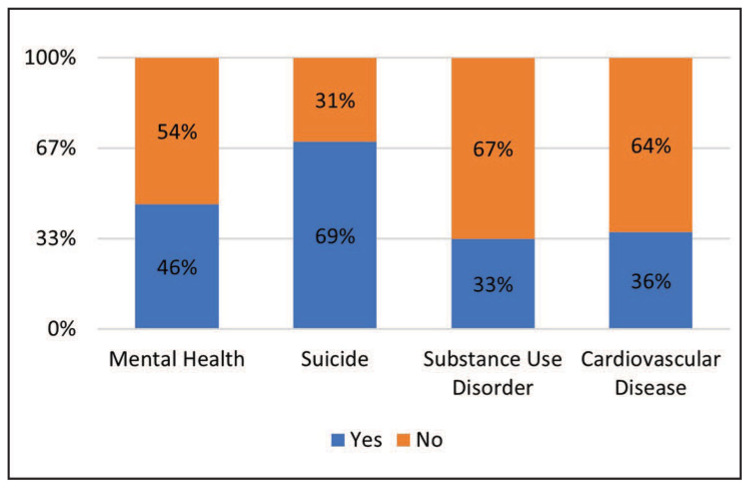

From 2017–2020, assessment was identified as a contributing factor for 46% of cases where the board determined that mental health conditions other than SUD contributed to the death. This explains why nearly one in four (24%) assessment recommendations addressed perinatal mental health. Further, assessment issues were identified in 69% of pregnancy-related suicide deaths, which were all determined to be preventable and all attributed to mental health conditions as the underlying cause of death (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Assessment Issues Identified in Pregnancy-Related Deaths

Additionally, assessment was identified as a contributing factor in 33% of cases where the board determined that SUD contributed to the death. These recommendations for systematic assessment focused on standardizing care to assess for SUD, utilizing validated screenings performed at multiple intervals throughout the pregnancy and postpartum period rather than relying on urine drug screens alone.

Cardiovascular disease is the second most common cause of pregnancy-related death after mental health conditions. More than one-third (36%) of these deaths had a recommendation for improved assessment. Special attention was given to screening for cardiomyopathy and both chronic and gestational hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP). This included recommendations for expanded training regarding HDP for all providers, especially emergency medicine physicians and primary care physicians, where patients often present for general health care. The board recommended that patients with a personal history of HDP or a family history of cardiovascular disease should have a baseline Blood Urea Nitrogen level, an echocardiogram, and an electrocardiogram if indicated.

Discussion

Based upon this analysis, the board determined the most immediate way to impact pregnancy-related deaths in Missouri is to improve patient assessment through maternal screenings, beginning with the initial obstetrician’s assessment and expanding to emergency department providers, pediatricians, intake nurses, nurse practitioners, family physicians, and health care systems in alignment with 2023 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines.7 In Missouri, the board has a 60/40 ratio of clinical to nonclinical members representing various disciplines, geographic regions, and organizations for quality case reviews. As such, this data may be skewed toward provider solutions as the board may be better able to identify issues at the provider level than at other levels. However, this also means that they are intimately aware of what is necessary for providers and their institutions to potentially impact maternal morbidity and mortality in Missouri.

Three themes that emerged as most prominent from these recommendations focused on improvements to assessment and provider knowledge regarding how to treat and refer patients using a warm handoff based on screening results when indicated. A warm handoff is a transition conducted in person, between two health care team members, in front of the patient (and family if present).8,9,10 The PAMR board recommended that all perinatal patients be screened for mental health conditions using validated tools (e.g., the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale or the Patient Health Questionnaire).11,12 Screening for substance use using validated tools available through the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse13 was also suggested.14,15

Intimate partner violence (IPV) screening was recommended; however, there were concerns about a patient’s ability to safely communicate this information without putting themselves at risk of harm, whether actual or perceived. Creating safe, nonjudgmental, and non-stigmatized health care settings is a critical step providers, and systems can take to increase trust and patient-provider communication. Screening for risk factors for these issues may require providers to innovate ways of communicating with patients, such as motivational interviewing to empower a patient to make behavioral changes in the case of substance use or providing a way to communicate that cannot be overheard or intercepted regarding IPV. The Safety Card for Reproductive Health, an evidence-based screening and intervention tool, is available.16

A provider’s knowledge of cardiovascular disorders associated with pregnancy (i.e., cardiomyopathy, hypertension, etc.) should include properly assessing, treating, referring, and educating patients on their diagnosis and risks.17 The board recommended that practices and procedures be standardized across both obstetric and nonobstetric providers, including emergency medicine physicians and primary care providers.18 While the utilization of specific AIM bundles was recommended, the need for other practices such as screening for current or recent pregnancies to determine optimum treatment pathways was also identified as nearly 45% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred between 43 and 365 days postpartum.

Conclusion

Maternal mortality both in the US and Missouri is unacceptably high, and the board’s findings underscore the significance of systematic assessment of obstetric patients by Missouri providers and health systems. The PAMR boards’ determination that improvements to assessment, specifically at the provider, facility, and system levels, could have potentially prevented the tragic loss of maternal life warrants further study. This study’s findings suggest an area for improvement where health care providers and their systems may directly and immediately begin working to significantly decrease pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity within the state of Missouri.

Footnotes

Daniel Quay, MA, Ashlie Otto, RN, Karen Harbert, MPH, and Crystal Schollmeyer, RN, BSN, are all with the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Jefferson City, Missouri. George Hubbell, MD, MS is an OB/GYN, in New Bloomfield, Missouri.

For More Information: For more information on the CDC Maternal Mortality Prevention, visit https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/mmrc/decisions-form.html.

Disclosure: No financial disclosures reported. Artificial intelligence was not used in the study, research, preparation, or writing of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2021 doi: 10.15620/cdc:124678. Published online March 16, 2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Declercq E, Zephyrin L. Severe maternal morbidity in the United States: A Primer. Commonwealth Fund; 2021. [Accessed: July 20, 2023]. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Declercq_severe_maternal_morbidity_in_US_primer_db.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Missouri Pregnancy Associated Mortality Review 2017 –2019 Annual Report. Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services; 2022. https://health.mo.gov/data/pamr/pdf/2020-annual-report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mock Panel. [Accessed January 19, 2024];Review to Action. https://reviewtoaction.org/practice/mock-panel . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maternal Mortality Committee Decisions Form. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024. [Accessed July 24, 2024]. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/media/pdfs/2024/05/mmria-form-v24-fillable-508.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quay D, Harbert K, Otto A. Cardiovascular Disease: A Hidden Threat to Maternal Health. Missouri Family Physician. 2023;42(3):12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline 4. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(6):1232–1261. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Content last reviewed. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jun, 2023. Warm Handoff: Intervention. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/reports/engage/interventions/warmhandoff.html . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand P, Desai N. Correlation of warm handoffs versus electronic referrals and engagement with mental health services co-located in a pediatric primary care clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2023;73(2):325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard ED. Transitions in care. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2018;32(1):7–11. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesh KK, Nadel H, Blewett D, Freeman MP, Kaimal AJ, Riley LE. Implementation of universal screening for depression during pregnancy: feasibility and impact on obstetric care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):517.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waqas A, Koukab A, Meraj H, Dua T, Chowdhary N, Fatima B, Rahman A. Screening programs for common maternal mental health disorders among perinatal women: report of the systematic review of evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Screening and Assessment Tools Chart. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Sep 27, 2023. [Accessed October 27, 2023]. https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/screening-tools-resources/chart-screening-tools . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;130:e81–e94. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright TE, Terplan M, Ondersma SJ, et al. The role of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the perinatal period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamberlain L, Levenson R. Addressing Intimate Partner Violence Reproductive and Sexual Coercion: A Guide for Obstetric, Gynecologic, Reproductive Health Care Settings. [Accessed February 7, 2023];Futures Without Violence. 2013 https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/file/HealthCare/Reproductive%20Health%20Guidelines.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pregnancy and Heart Disease. ACOG Practice Bulletin 212. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e320–e356. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown HL, Warner JL, Gianos E, et al. Promoting Risk Identification and Reduction of Cardiovascular Disease in Women Through Collaboration With Obstetricians and Gynecologists: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(10):574–576. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]