Abstract

Background

Combined Immuno‐chemotherapy consisting of gemcitabine, cisplatin and the programmed death‐ligand one inhibitor durvalumab (GCD) is the new standard of care for patients with biliary tract cancers (BTC) based on positive results of the TOPAZ‐1 study.

Objective

We here evaluated the efficacy and safety of GCD for BTC in a German multicenter real‐world patient cohort.

Methods

Patients with BTC treated with GCD from 9 German centers were included. Clinicopathological baseline parameters, overall survival (OS), response rate and adverse events (AEs) were retrospectively analyzed. The prognostic impact was determined by Kaplan–Meier analyses and Cox regression models.

Results

A total of 165 patients treated with GCD between 2021 and 2024 were included in the study. Median OS and median progression‐free survival were 14 months (95% CI 10.3–17.7) and 8 months (95% CI 6.8–9.2), respectively. The best overall response rate was 28.5% and disease control rate was 65.5%. While extrahepatic and intrahepatic BTC showed similar outcomes, mOS was significantly shorter in patients with gall bladder cancer (GB‐CA) with 9 months (95% CI 5.5–12.4; p = 0.02). In univariate analyses age ≥70 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) ≥1, status post cholecystectomy, GB‐CA and high baseline CRP values were significantly associated with OS. ECOG PS ≥ 1 and GB‐CA remained independent prognostic factors for OS in multivariable cox regression analysis. AEs have been reported in 130 patients (78.8%), including 149 grade 3–4 AEs (25.5%). One patient died of severe infectious pneumonia. Immune‐related (ir)AEs occurred in 17 patients (10.3%), including 9 grade 3–4 irAEs (2.2%), which led to treatment interruption in 4 patients.

Conclusions

Immuno‐chemotherapy in patients with BTC was feasible, effective and safe in a real‐life scenario. Our results were comparable to the phase 3 clinical trial results (TOPAZ‐1). Reduced efficacy was noted in patients with GB‐CA and/or a reduced performance status that warrants further investigation.

Keywords: biliary tract cancers, check‐point inhibition, cholangiocarcinoma, cisplatin, durvalumab, gemcitabine, immuno‐chemotherapy, programmed death‐ligand 1 inhibitor

Key summary.

Summarize the established knowledge on this subject

Biliary tract cancers comprise a highly heterogenous group of tumors that are mainly classified by their anatomic localization.

Following positive results from the TOPAZ‐1 trial immuno‐chemotherapy of gemcitabine, cisplatin and durvalumab is the new standard of care for unselected patients with advanced or recurrent biliary tract cancers.

Results of the TOPAZ‐1 trial generally demonstrated consistent benefit for immuno‐chemotherapy across all subgroup analyses.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

Immuno‐chemotherapy in patients with biliary tract cancer was feasible, effective and safe in a real‐life scenario.

Patients with a reduced performance status and/or gall bladder cancer had a significantly worse outcome.

The rate of immune‐related adverse events did not differ in patients with immune‐related disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Biliary tract cancer (BTC) represents the second‐most common primary liver cancer. BTCs comprise a highly heterogenous group of tumors that are classified by anatomic localization into intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (eCCAs) as well as gallbladder cancer (GB‐CA). 1 , 2

Despite the recent progress in loco‐regional and systemic therapies, oncological resection remains the only curative approach for patients with BTCs. However, recurrence rates are high, limiting the overall clinical outcome of affected patients. In patients with irresectable recurrence and/or advanced‐stage of disease, systemic treatment is the therapy of choice. 3 For more than a decade, chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin represented the standard in first‐line treatment based on the results of the phase 3 ABC‐02 trial. 4 Intensified chemotherapy regimens with mFOLFIRINOX or addition of nab‐paclitaxel to gemcitabine and cisplatin did not result in a statistically significant improvement of mOS and mPFS in unselected patients with BTC in clinical trials in comparison to gemcitabine and cisplatin alone. 5 , 6 Moreover, triple chemotherapy resulted in higher rates of treatment‐related adverse events (TRAE). In contrast, adding immunotherapy with the novel checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin significantly increased the outcome of patients with BTC as recently shown within the TOPAZ‐1 study. 7 This double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial included 685 patients with locally advanced or metastatic BTC, who received up to 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy followed by a durvalumab or placebo maintenance therapy every 4 weeks until clinical or imaging‐based disease progression or until unacceptable toxicity. Results of the study demonstrated a significantly improved mOS of 12.8 months in comparison to 11.5 month with chemotherapy alone (HR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.66–0.97; p = 0.021) and a significantly improved median progression‐free survival (mPFS) of 7.2 months in comparison to 5.7 months with chemotherapy alone (HR = 0.75; 95% CI = 0.63–0.89; p = 0.001). The safety profile did not differ between treatment arms. The European Medical Agency (EMA) approved the use of durvalumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin as first‐line treatment for advanced BTC in December 2022. Real‐world data on the use of novel immuno‐chemotherapy combinations in BTC is limited. An early access program in Italy including 145 patients with advanced BTC mostly confirmed results achieved in the TOPAZ‐1 trial, but especially data on subgroups and independent prognostic factors are scarce. 8 , 9 Here we comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and safety of gemcitabine, cisplatin and durvalumab (GCD) in a large real‐world cohort of 165 patients with BTCs from 9 German academic centers. We thoroughly describe the treatment course of GCD in current clinical management. Our results demonstrate the safe and efficient use of GCD in various patients with BTC. However, we note differential outcomes in patients with a reduced performance status and/or GB‐CA.

METHODS

Study cohort and study design

Patients with advanced or metastatic BTCs including intrahepatic, perihilar and distal CCAs as well as GB‐CA, treated with gemcitabine, cisplatin and durvalumab were included in this retrospective multicenter study. Patient data from nine German academic centers were evaluated for baseline demographic data, history of the disease, treatment course, radiological results, and histological and molecular pathological reports. Available laboratory values for bilirubin, albumin, C‐reactive protein (CRP) and carbohydrate‐antigen 19‐9 (CA19‐9) prior treatment were documented. The primary endpoint was overall survival. Secondary endpoints were PFS, response rates and safety. The study was approved by the local ethics committee as well as the ethics committees of the individual centers for retrospective analyses of clinical data. The study was conducted following the STROBE cohort checklist and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Guidance for Reporting Oncology Real‐World Evidence (GROW). 10 , 11

Treatment and study assessments

Durvalumab was administered intravenously at a fixed dose of 1500 mg on day 1 of a 21‐day cycle in combination with gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) and cisplatin (25 mg/m2), which were administered on days 1 and 8 of each cycle. Patients treated per the TOPAZ‐1 protocol received durvalumab monotherapy every 4 weeks until clinical or imaging disease progression or until unacceptable toxicity after completion of up to 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy. Treatment application or dose modifications were defined by local standards. Median duration of treatment was defined as the time from the first administration until the last documented administration. Patients still receiving treatment at the data cutoff were censored.

OS was analyzed from the start of GCD treatment until last follow up or death. PFS was analyzed from the start of GCD treatment until last follow‐up or progression or death, whichever occurred first. Patients with at least one follow‐up imaging assessment were evaluable for radiological response. Radiological response was evaluated by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and defined as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) by local investigators. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0.2.0 (SPSS Inc.). Categorical and continuous data were expressed as numbers with percentages and median with the interquartile range (IQR), respectively. Differences between categorical variables were calculated using Pearson's Chi‐square test. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and medians were compared using the log rank (Mantel–Cox) test. Survival data were reported as median values in months, with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted using Cox regression models to identify prognostic factors for OS. Variables with a p value < 0.05 in univariate analyses were considered for multivariate analysis. Hazard ratios (HR) were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Differences between categorical variables were calculated using Pearson's Chi‐square test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 165 patients with BTC treated with GCD between 2021 and 2024 were included in the study. Clinicopathological baseline data are summarized in Table 1. The median age of the study population was 63 years (25–75 IQR, 56–68) with a median BMI of 24 kg/m2 (25–75 IQR, 22–29) including 86 (51.5%) male and 79 (47.9%) female patients. The most common type of BTC was iCCA (60.6%) followed by eCCA (28.5%) including pCCA (20%) and dCCA (8.5%), and GB‐CA (10.9%). Tumor grading was reported for 102 patients (61.8%) with a G1/2/3 grades of 2.4%, 39.4% and 20%, respectively. Molecular profiling was performed in 140 patients by local molecular‐pathological assessments (85%), detecting molecular alterations in 108 patients (65%) (Table 1). Although clinicopathological baseline and treatment parameters did not significantly differ between anatomic types of BTC, their molecular profiles were significantly different. The main alterations in iCCAs were FGFR2 alterations (16%) and IDH1 or 2 mutations (16%) and in eCCAs KRAS (43%) and TP53 (35%). In GB‐CAs, alterations occurred mainly in TP53 (46.7%) and Her2 (13.3%), respectively (Table S1).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathological baseline and treatment parameters.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Median (25–75 percentile) | |

| Total | 165 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 86 (51.5) |

| Female | 79 (47.9) |

| Age | 63 (56–68) |

| BMI | 24 (22–29) |

| CCA type | |

| iCCA | 100 (60.6) |

| eCCA | 47 (28.5) |

| GB‐CA | 18 (10.9) |

| Tumor grading | |

| 1 | 4 (2.4) |

| 2 | 65 (39.4) |

| 3 | 33 (20.0) |

| Molecular alterations | |

| MSI | 5 (3.0) |

| FGFR2 alterations (mutation or Fusion/Re‐Arrangements) | 13 (7.8) |

| IDH1 or 2 | 13 (7.8) |

| KRAS | 28 (16.9) |

| BRAF | 8 (4.8) |

| PIK3CA | 6 (3.6) |

| TP53 | 32 (19.4) |

| Her2 alterations | 8 (4.8) |

| BRCA1/2 | 7 (4.2) |

| ERBB2 | 5 (3.0) |

| Others (n ≤ 1) | 5 (3.0) |

| Comorbidities/risk factors | |

| Cholelithiasis | 19 (11.5) |

| Autoimmune‐disease | 13 (7.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 25 (15.1) |

| Chronic liver disease: | 23 (13.9) |

| Viral Hepatitis B or C | 10 (6.0) |

| MASLD/MASH | 9 (5.5) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 11 (6.6) |

| Cholecystectomy | |

| Yes | 59 (35.8) |

| No | 104 (63.0) |

| ECOG a | |

| 0 | 98 (59.4) |

| 1 | 53 (32.1) |

| 2 | 6 (3.6) |

| Distant Metastases b | |

| Yes | 113 (67.9) |

| No | 52 (31.5) |

| Prior resection | 53 (32.1) |

| Prior neoadjuvant treatment | 6 (3.6) |

| Prior adjuvant treatment | 34 (20.6) |

| First‐line GCD treatment | |

| Yes | 134 (81.2) |

| No | 31 (18.7) |

| Time under treatment (month) | 4 (2–7) |

| Further systemic treatments | |

| Second‐line | 62 (37.6) |

| Third‐line | 17 (10.3) |

| Further lines | 5 (3.0) |

| Targeted treatments | 16 (9.7) |

| CA 19‐9 | |

| High | 71 (43.0) |

| Low | 72 (43.6) |

| CRP | |

| High | 66 (40.0) |

| Low | 66 (40.0) |

| ALBI‐score | |

| 1 | 87 (52.7) |

| 2 | 29 (17.6) |

| 3 | 6 (3.6) |

| Bilirubin | |

| ≤2.5 × ULN | 156 (94.5) |

| >2.5 × ULN | 9 (5.5) |

Abbreviations: ALBI, Albumin Bilirubin; CA19‐9, carbohydrate antigen 19‐9; CRP, C‐reactive protein; dCCA, distant cholangiocellular carcinoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; GB‐CA, gall bladder cancer; GCD, Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, Durvalumab; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma; MASLD/MASH, metabolic dysfunction‐associated steatotic liver disease/metabolic associated steatohepatitis; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocellular carcinoma; ULN, upper limit normal.

ECOG at start GCD.

Distant metastases at start of systemic treatment.

Frequent comorbidities and/or risk factors for BTC were diabetes mellitus (15.1%), cholelithiasis (11.5%), and chronic liver diseases (CLD; 14%) including 11 patients with liver cirrhosis (6.6%), 10 patients with chronic viral hepatitis B or C infection (6%) and 9 patients with metabolic‐dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease/steatohepatitis (MASLD/MASH: 5.5%). The major underlying etiologies of liver cirrhosis were chronic viral hepatitis B or C in 5 patients and MASLD/MASH in 2 patients. Hepatic function was preserved in the majority of patients of our real‐world cohort with an albumin‐bilirubin (ALBI) grade of 1 in 52.7%, 2 in 17.6% and 3 in 3.6% of the patients. Patients with liver cirrhosis had mainly a Child–Pugh score A 5–6 (n = 10). The cohort included one patient with a Child–Pugh class B 9. Complications of liver cirrhosis were present in 6 patients, including mild ascites (n = 3) and presence of esophageal varices (n = 3). None of these patients suffered from hepatic encephalopathy.

Concomitant autoimmune diseases were present in 13 patients (7.8%), including primary sclerosing cholangitis (n = 3), chronic inflammatory bowel disease (n = 6) treated with mesalazine (n = 3) or low‐dose prednisolone (5 mg; n = 1), and rheumatic diseases (n = 4) treated with leflunomide (n = 1) or secukinumab (n = 1).

Patients were catagorized into low and high by the median for further analyses. The tumor marker, CA19‐9, was reported in 143 patients (86.6%) with a median of 39 kU/l and a CRP value was available in 132 patients (80%) with a median of 19,7 mg/L prior to treatment with GCD. Hyperbilirubinemia of >2.5 upper limit normal (ULN) was present in 9 patients.

Prior and consecutive treatments

Treatment parameters are summarized in Table 1. Overall, prior resection in curative attempt had been performed in 53 patients (32.1%) with adjuvant treatment in 34 patients (20.6%). Neoadjuvant treatment was administered in cases of locally advanced stage or in a study setting in 3.6% of patients including one patient, who received GCD in a neoadjuvant setting and who was re‐exposed at the time of recurrence.

In total, 61 patients (37.6%) received a consecutive treatment after first‐line systemic treatment, 17 patients (10.3%) received a third‐line and 5 patients (3%) received more than three systemic treatment lines. Targeted treatments were given in 16 patients (9.7%) most commonly in iCCA (87.5%; iCCA (n = 14); pCCA (n = 1); GB‐CA (n = 1)) as second‐line (n = 6), third‐line (n = 4) or later line (n = 6) of treatment. Inhibitors of FGFR2 (n = 6) and IDH1 (n = 4) were most frequently used.

GCD treatment

The majority of patients (n = 134; 81.2%) received GCD treatment as first‐line systemic treatment; the minority (n = 31; 18.8%) received chemotherapy only (Table 1). Most commonly, gemcitabine, cisplatin, was applied by adding durvalumab during the treatment course after approval by the EMA. In total, 37 patients received GCD treatment before official approval under off‐label conditions. These patients had less commonly a chronic liver cirrhosis/cholelithiasis and higher CA19‐9 as well as lower CRP levels prior to treatment (Table S2).

Distant metastases were detected in 113 patients (67.9%) at the start of systemic treatment. The performance status of patients at the start of GCD treatment was sufficient with an ECOG of 0 in 59.4%, 1 in 32.1% and 2 in 3.6% of the patients.

The median duration of GCD treatment was 4 months (25–75 IQR, 2–7). Overall, 49 patients completed 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy, of which 33 patients (20%) received durvalumab maintenance treatment every four weeks until clinical or imaging proven disease progression in alignment with the TOPAZ‐1 study. In total, 116 patients (70.3%) were not treated per TOPAZ‐1 protocol: 12 patients (7.2%) received more than 8 cycles of immuno‐chemotherapy and 104 patients (63.0%) received less than 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy. Of those 116 patients, durvalumab maintenance treatment was performed in 20 patients (12.1%). In total, 36 patients, who received less than 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy, were still on treatment at the time of data cut. In 71 patients, treatment was either completely stopped or chemotherapy was stopped only due to progression at the time of first staging (n = 33), toxicity to chemotherapy (n = 14), death (n = 13), patient wishes (n = 5) or other reasons (n = 6). A re‐challenge of gemcitabine and cisplatin under durvalumab maintenance treatment was performed in 5 patients due to disease progression. Re‐challenge was stopped in 2 patients due to toxicity and/or progression; 3 patients had ongoing treatment at the time of data cut.

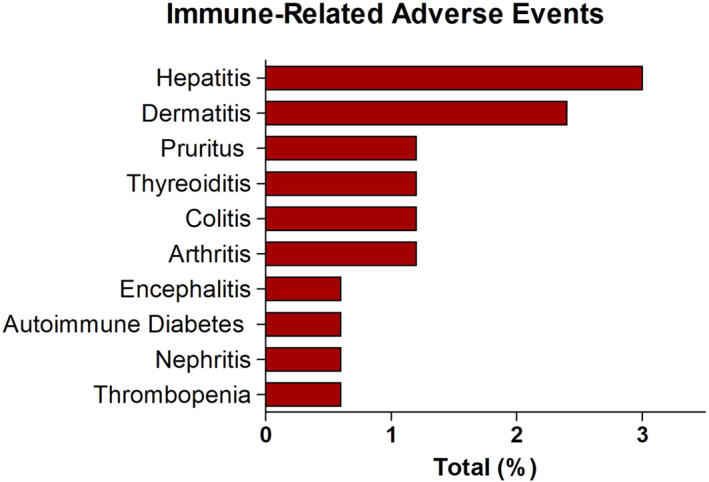

Safety

Overall, 419 AEs were reported in 130 patients (78.8%), including 269 grade 1–2 AEs (64.2%) and 149 grade 3–4 AEs (25.5%; Table 2). One patient died of severe infectious pneumonia. The most common AEs were thrombopenia (27.9%), neutropenia (26.1%), anemia (25.5%), nausea (18.8%), infections (15.8%) and fatigue (13.3%; Figure S1). Immune‐related (ir)AEs occurred in 17 patients (10.3%), including 12 grade 1–2 irAEs (2.9%) and 9 grade 3–4 irAEs (2.2%). The most common irAEs were ir‐hepatitis (3.0%) and ir‐dermatitis (2.4%; Figure 1). Treatment was discontinued due to AEs in 14 patients, including 4 patients with severe irAEs such as ir‐hepatitis (n = 2), ir‐diabetes mellitus (n = 1) and ir‐encephalitis (n = 1).

TABLE 2.

Adverse events (AE) under treatment with Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, Durvalumab.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| AE | |

| Total | 419 (100) |

| Immune‐related | 21 (5.0) |

| Grade 1–2 | |

| Total | 269 (64.2) |

| Immune‐related | 12 (2.9) |

| Grade 3–4 | |

| Total | 149 (35.5) |

| Immune‐related | 9 (2.2) |

| Grade 5 | |

| Total | 1 (0.2) |

| Immune‐related | 0 (0) |

| AE resulting in EOT | |

| Total | 14 (3.4) |

| Immune‐related | 4 (0.9) |

Abbreviation: EOT, end of treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Most common immune‐related adverse events.

In patients with chronic liver disease, the safety profile was comparable to the main cohort (Table S3). Two patients with liver cirrhosis Child–Pugh A 6 and B 9 stopped treatment due to decompensation in the context of an infection and one due to ir‐hepatitis grade 3–4. In patients with a significant hyperbilirubinemia, cholangitis grade–4 occurred in 4 patients. None of the affected patients had to permanently discontinue treatment. The cohort also included 13 patients with autoimmune diseases including co‐morbidity of primary sclerosing cholangitis (n = 3), chronic inflammatory bowel disease (n = 6) treated with mesalazine (n = 3) or low‐dose prednisolone (5 mg; n = 1), and rheumatic diseases (n = 4) treated with leflunomide (n = 1) or secukinumab (n = 1). Of those, only one patient discontinued treatment due to an immune‐related adverse event, which was ir‐hepatitis grade 4 (Table S3).

Response

Median follow‐up was 9 months (95% CI 7.6–10.4). In total, 51 patients died at the time of data‐cut. First staging was available in 142 patients with ORR of 26%, including 4 (2.4%) CR and 39 (23.6) PR. SD was reported in 38.8% with a DCR of 64.8%. Thirty five patients (21.2%) had PD at first staging. Results of the reported best overall response were similar to first staging and are summarized in Table 3. Patients, who received GCD as first‐line systemic treatment (n = 134) displayed an ORR of 31% and DCR of 67%, which was significantly better in comparison to patients, who received GCD as a second or later‐line systemic treatment (Table S4). Response assessment under durvalumab maintenance treatment was reported in 39 patients with a best ORR of 11.4% and a DCR of 45.5% (Table 3). Response was not significantly different in patients with irAEs (n = 17; 10.3%) in comparison to patients without irAEs (Table S5).

TABLE 3.

Response to treatment.

| First staging | Best response | Best response 1L GCD a | Best response durva mono | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Total | 165 (100) | 165 (100) | 134 (100) | 53 (100) |

| ORR | 43 (26.0) | 47 (28.5) | 42 (31) | 6 (11.4) |

| CR | 4 (2.4) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (2) | 3 (5.7) |

| PR | 39 (23.6) | 43 (26.1) | 39 (29) | 3 (5.7) |

| SD | 64 (38.8) | 61 (37.0) | 48 (36) | 18 (34.0) |

| DCR | 107 (64.8) | 108 (65.5) | 90 (67) | 24 (45.4) |

| PD | 35 (21.2) | 33 (20.0) | 21 (16) | 15 (28.3) |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Patients, who received GCD as first‐line (1L) systemic treatment.

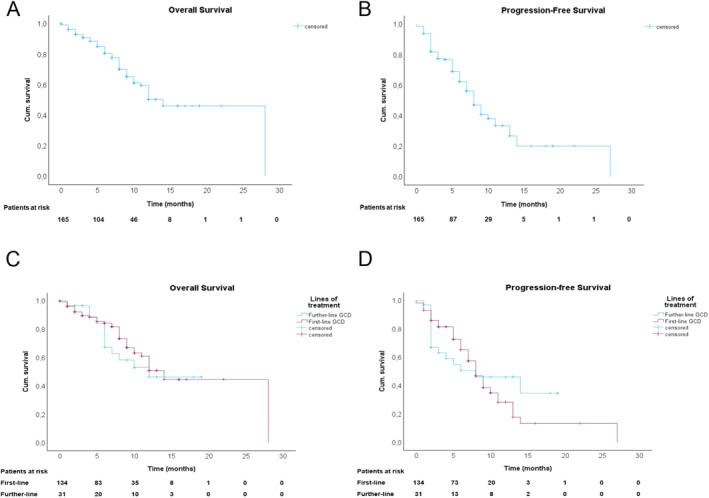

Survival

Median OS of the study cohort was 14 months (95% CI 10.3–17.7) and median PFS was 8 months (95% CI 6.8–9.2; Figure 2 a,b). Median OS of patients who received GCD as first‐line systemic treatment (n = 134) was also 14 months (95% CI 11.1–16.9) and median PFS was 8 months (95% CI 6.8–9.2). No significant differences were observed between patients who received GCD as a later‐line systemic treatment (Figure 2c,d).

FIGURE 2.

Overall and progression‐free survival of patients with biliary tract cancers. (a) Cumulative overall survival estimates to death from the start of GCD treatment. (b) Cumulative progression‐free survival estimates to progression from start of GCD treatment. (c) Cumulative overall survival estimates to death from start of GCD treatment stratified to treatment line. (d) Cumulative progression‐free survival estimates to progression from start of GCD treatment stratified to treatment line.

We further analyzed outcome with regard to the treatment course for patients without noticeable progression at the time of first staging: Interestingly, patients who completed 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy in alignment with the TOPAZ‐1 study protocol (n = 49) showed a similar outcome compared to patients who received more than 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy (n = 12). However, survival was significantly shorter in patients, who received less than 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy without noticeable progression at the time of first staging (n = 71; Figure S2A,B).

Furthermore, we analyzed special subgroups of patients with BTC and detected that the occurrence of irAEs was associated with a trend to better outcome with a mOS not reached versus 12 months (95% CI 9.3–14.7; p = 0.35) and mPFS of 11 months (95% CI 3.4–18.5) versus 8 months (95% CI 7.1–8.9; p = 0.401; Figure S2C,D). Overall, mOS and mPFS in patients with chronic liver diseases, hyperbilirubinemia or autoimmune diseases were similar to the rest of patient cohort (Figure S3A–F).

In univariate cox regression analyses age (≥70 vs. <70 years: HR 2.6; 95% CI 1.4–4.6; p = 0.002), performance status (ECOG 0 vs. ≥1: HR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2–0.7; p = 0.001), status post cholecystectomy (yes vs. no: HR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–0.9; p = 0.028), GB‐CA (GB‐CA vs. other BTCs: HR 2.4; 95% CI 1.2–4.6; p = 0.012) and a high pretreatment CRP value (high vs. low divided by the median: HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.0–3.5; p = 0.038) were significantly associated with OS (Table 4). Performance status (ECOG 0 vs. ≥1: HR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2–0.9; p = 0.022) and GB‐CA (GB‐CA vs. other BTCs: HR 2.6; 95% CI 1.1–5.9; p = 0.029) remained independent prognostic factors for OS in multivariate cox regression analysis.

TABLE 4.

Univariable and multivariable cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Sex, male versus female | 1.5 (0.9–2.7) | 0.140 | ||

| Age, ≥70 versus <70 | 2.6 (1.4—4.6) | 0.002 | 1.7 (0.9–3.5) | 0.119 |

| ECOG, a 0 versus ≥1 | 0.4 (0.1—0.7) | 0.001 | 0.4 (0.2—0.9) | 0.022 |

| UICC, stage 4 versus stage 1–3 | 2.7 (1.4—5.1) | 0.003 | ||

| Distant metastases, b yes versus no | 1.8 (0.9–3.6) | 0.080 | ||

| Cholecystectomy, yes versus no | 0.5 (0.3—0.9) | 0.028 | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 0.690 |

| Risk factor liver cirrhosis, yes versus no | 0.9 (0.2–3.9) | 0.942 | ||

| Risk factor diabetes, yes versus no | 1.6 (0.8–3.3) | 0.162 | ||

| Risk factor MASLD/MASH, yes versus no | 1.0 (0.3–3.2) | 0.995 | ||

| Risk factor viral hepatitis B or C, yes versus no | 0.9 (0.2–3.6) | 0.868 | ||

| Risk factor cholelithiasis | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) | 0.883 | ||

| Type, iCCA versus other BTCs | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 0.061 | ||

| Type, eCCA versus other BTCs | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.787 | ||

| Type, GB‐CA versus other BTCs | 2.4 (1.2—4.6) | 0.012 | 2.6 (1.1—5.9) | 0.029 |

| Tumor grading, G3 versus G1/G2 | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | 0.997 | ||

| Therapy line GCD, 1st versus later line | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.804 | ||

| TOPAZ‐1 therapy protocol, yes versus no | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.812 | ||

| Immune‐related AE, yes versus no | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 0.375 | ||

| Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio, >3 versus <3 | 2.1 (0.8–5.8) | 0.137 | ||

| CRP, high versus low | 1.9 (1.0—3.5) | 0.038 | 1.5 (0.7–2.9) | 0.227 |

| CA19‐9, high versus low | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 0.230 | ||

| ALBI‐score, 1 versus >1 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.165 | ||

| Bilirubin, ≤2.5 versus >2.5 × ULN | 0.7 (0.2–2.9) | 0.608 | ||

| Targetable molecular alteration, yes versus no | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.127 | ||

| Molecular alteration, yes versus no | ||||

| MSI | 0.1 (0.0–29) | 0.351 | ||

| FGFR2‐alterations (mutation or Fusion/Re‐Arrangements) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) | 0.336 | ||

| IDH1 or 2 | 0.5 (0.2–1.6) | 0.259 | ||

| KRAS | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) | 0.510 | ||

| BRAF | 0.9 (0.2–3.8) | 0.905 | ||

| PIK3CA | 0.8 (0.2–3.3) | 0.744 | ||

| TP53 | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 0.671 | ||

| Her 2 alterations | 2.6 (0.7–11.3) | 0.196 | ||

| BRCA1/2 | 0.1 (0.0–25) | 0.339 | ||

| ERBB2 | 3.5 (0.8–14.9) | 0.091 | ||

Note: Bold means significant finding.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ALBI, Albumin Bilirubin; BTC, biliary tract cancer; CA19‐9, carbohydrate antigen 19‐9; CRP, C‐reactive protein; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; GB‐CA, gall bladder cancer; GCD, Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, Durvalumab; MASLD/MASH, metabolic dysfunction‐associated steatotic liver disease/metabolic associated steatohepatitis.

ECOG at start of GCD.

Distant metastases at the start of of systemic treatment.

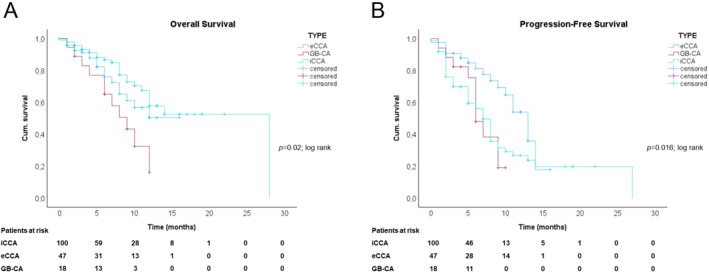

Survival was significantly shorter for patients with GB‐CA with a median OS of 9 months (95% CI 5.5–12.4; p = 0.02) in comparison to patients with iCCAs and/or eCCAs (mOS not reached; Figure 3a). The mPFS for patients with GB‐CA was 6 months (95% CI 4.6–7.4), for patients with iCCA 7 months (95% CI 5.8–8.1; ns), and for patients with eCCAs 13 months (95% CI 10.5–15.5; p = 0.015; Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Overall and progression‐free survival of patients with biliary tract cancers. (a) Cumulative overall survival estimates to death from start of GCD treatment stratified to CCA‐type. (b) Cumulative progression‐free survival estimates to progression from start of GCD treatment stratified to CCA‐type.

DISCUSSION

Here we evaluated the efficacy and safety of the immuno‐chemotherapy GCD in patients with BTCs. This combination was approved by the EMA in 2022 based on positive results of the phase 3 TOPAZ‐1 study with significant improvement of mOS of 12.8 months (HR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.66–0.97; p = 0.021) and mPFS of 7.2 months in comparison to chemotherapy alone (HR = 0.75; 95% CI 0.63–0.89; p = 0.001). 7 Immuno‐chemotherapy is now considered a new standard of care in the first‐line setting for unselected patients with BTC.

In the present study, we confirmed significant benefits of immuno‐chemotherapy in a real‐life setting. Overall, mOS reached even 14 months (95% CI 10.3–17.7) and mPFS 8 months (95% CI 6.8–9.2). ORR of 28.5% was comparable to 26.7% in the TOPAZ‐1 trial. Most patients (81.2%) received GCD treatment as first‐line systemic treatment. Those patients had significantly better ORR compared to patients receiving GCD treatment as a further line of systemic treatment supporting its upfront use. In total, 49 patients completed 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy, of which 33 patients (20%) received durvalumab maintenance treatment every four weeks until clinical or imaging proven disease progression in alignment with the TOPAZ‐1 study. Interestingly, outcome was not different compared to patients, who received more than 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy, but significantly better when compared to patients who received less than 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy. Recently, pembrolizumab in combination with GC has been approved for first‐line treatment of BTC based on results of the KEYNOTE‐966 trial. 12 This phase III study demonstrated superiority over gemcitabine and cisplatin alone and the combination of pembrolizumab to GC has also been approved for first‐line treatment. Besides using a different check‐point inhibitor, one important difference between the TOPAZ‐1 and KEYNOTE‐966 trials is that in the latter, only cisplatin was stopped after 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy. The duration of gemcitabine was not limited, whereas in the TOPAZ‐1 trial, both, cisplatin and gemcitabine, were stopped after 8 cycles. 7 , 12 Our results indicate that a maintenance treatment with durvalumab after 8 cycles of combined treatment did not affect clinical outcome. Furthermore, a prolonged chemotherapy for more than 8 cycles did not result in better survival rates in patients with BTCs (Figure S2A,B). Importantly, patients who did not complete 8 cycles of combined treatment displayed a significantly reduced mOS.

On the one hand, this result could indicate the necessity for an adequate induction therapy. On the other hand, it could reflect a subgroup of patients with innate chemoresistance and therefore worse prognosis who stopped immunochemotherapy before completing 8 cycles due to lack of efficiency. We acknowledge that our data has certain limitations due to short follow‐ups and its retrospective design. However, our results confirm that maintenance with durvalumab alone after 8 cycles of combined immuno‐chemotherapy is both feasible and effective.

In total, 61 patients (37.6%) received one or more regimens of subsequent anticancer therapy after discontinuation of first‐line treatment, which is consistent with the rate of 42.5% reported in the TOPAZ‐1 trial. Targeted treatments were applied in 16 patients (9.7%) mainly in iCCA (87.5%) using inhibitors for FGFR2 alterations and IDH1 mutations. This reflects current achievements in the field of precision medicine for patients with iCCAs made by deep sequencing approaches. 3 , 13 , 14 , 15

Interestingly, we demonstrated that a reduced ECOG PS of ≥1 and/or GB‐CA were independent prognostic factors for OS in uni‐ and multivariate cox regression analyses. While a reduced ECOG PS is a well‐known negative prognostic factor for patients with advanced BTC as described previously, 8 , 16 we describe for the first‐time a significantly different outcome of patients with regard to their anatomical subtype. Despite the limited number of patients, mOS of GB‐CA only reached 9 months and was thus significantly shorter than BTCs of other locations (95% CI 5.5–12.4; p = 0.02; Figure 3a). This observation is in contrast to results of the TOPAZ‐1 trial that generally demonstrated consistent benefit for immuno‐chemotherapy across all subgroup analyses. In this context, results of the SWOG 1815 phase 3 clinical trial investigating an intensified treatment regimen adding nab‐paclitaxel to gemcitabine and cisplatin (GAP) comparing efficacy and safety to GC alone, are of particular importance. 5 The study included 441 patients with 67% iCCA, 17% eCCA, and 16% GB‐CA. Results did not demonstrate a significant benefit of intensified chemotherapy for unselected patients with BTC in comparison to GC alone with a mOS of 14 versus 12.7 months (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.74–1.19, p = 0.58), mPFS of 8.2 versus 6.4 months (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.72–1.16, p = 0.47), and ORR of 34% versus 25% (p = 0.11). However, exploratory analyses described a mOS of 17.0 months for patients with GB‐CA (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.41–1.35, p = 0.33) treated with GAP in comparison to 9.3 months in the control arm as well as a significantly better ORR of 50% versus 24% (p = 0.09). Therefore, future studies should investigate if patients with GB‐CA might have a favorable clinical outcome in response to an intensified chemotherapy regimen.

Interestingly, while clinicopathological baseline and treatment parameters as well as safety profile were comparable between anatomic CCA types of our cohort, we observed significant differences only in terms of their mutational profiles (Table S1). Detected molecular profiles match the known distribution of molecular alterations including FGFR2 alterations (16%) and IDH1 or 2 mutations (16%) in iCCA, KRAS (43%) and TP53 (35%) in eCCAs as well as Her2 (13.3%) in GB‐CAs among others. 17 , 18 , 19 In the TOPAZ‐1 trial, a consistent benefit for immuno‐chemotherapy across genetically altered tumors has been reported. 7 However, in other studies, molecular subtypes have been linked to overall survival and response to immune‐therapy. 20 , 21 In fact, Rimini et al. revealed that different genomic cluster impact response in BTC treated with GCD. 22 Although the sample size was low in the study (n = 51) and further validation on larger and external cohorts are needed, the study supports the idea that genomic background of BTCs might impact efficacy and outcome to immuno‐chemotherapy.

In total, patients in our cohort had less AEs (78.8%) including less grade 3–4 AEs (25.5%) in comparison to 99.4% total AEs and 75.7% grade 3–4 AEs in the TOPAZ‐1 trial. Notably, these differences might be attributable to its retrospective nature as well as to the shorter follow‐up in the present study. Consistent with the results of the TOPAZ‐1 trial, most common AEs were mainly related to chemotherapy including cytopenia and nausea. IrAEs occurred only in 10.3% of patients including 2.2% grade 3–4 irAEs. Similar rates have been described in the TOPAZ‐1 trial with 12.7% irAEs including 2.4% grade 3–4 irAEs. Specific subgroups are commonly underrepresented in high selected populations of clinical trials. The TOPAZ‐1 trial did not include patients with chronic liver diseases with reduced liver function, patients with significant hyperbilirubinemia (>2.5 × ULN) and/or patients with immune‐related diseases and/or significant immune‐suppressive treatments. In our real‐world cohort, we included 23 patients with chronic liver diseases (including 10 patients with chronic viral hepatitis B or C and 11 patients with liver cirrhosis), 9 patients with significant hyperbilirubinemia and 13 patients with autoimmune disease and/or immunosuppressive medication. We demonstrate that these subgroups harbor similar outcomes and safety profiles compared to the rest of the patient cohort (Figure S3A–F, Table S3). Although overall rates of AEs might be underestimated in retrospective studies in comparison to prospective randomized trials, events of treatment discontinuation due to AEs are reliable safety markers in real‐world cohort studies. In the present study, treatment was discontinued due to AEs in 14 patients (8.4%), including only 4 patients (2.4%) with severe irAEs (Table 2). In the special subgroups, only three patients with CLD discontinued treatment due to hepatic decompensation in the context of an infection (n = 2) or due to ir‐hepatitis grade 3–4 (n = 1). In patients with significant hyperbilirubinemia, cholangitis grade–4 occurred frequently (n = 4), but none of those patients had to permanently discontinue treatment. In patients with concomitant autoimmune disease, only one patient had to stop treatment because of an ir‐hepatitis grade 3–4 (Table S3). In the TOPAZ‐1 trial, 44 patients (13%) discontinued treatment due to AEs, including 30 patients with treatment‐related AEs (8.9%). The study does not report the rate of treatment discontinuation due to irAEs; however, the overall rate of severe irAEs was low (2.4%). Therefore, the present data underlines the safe use of immuno‐chemotherapy in patients with BTCs with manageable side‐effects. Considering that 23 patients suffered from CLD, 9 patients had significant hyperbilirubinemia and 13 patients were treated despite having underlying autoimmune diseases and/or immune‐suppressive medication, our data emphasizes the safe use of GCD in these patients under close monitoring of potential AEs. Given the limited sample size, further validation is certainly required. However, recent data also support the observation that immunotherapy in patients with controlled autoimmune diseases can be safely administered. 23 Furthermore, growing knowledge of irAE management will improve the clinical management of patients with irAEs in the near future. 24 Interestingly, recent evidence indicates that patients who experienced irAEs might have improved response and outcome to immunotherapy across a variety of solid tumors. 25 , 26 , 27 In the present study, we did not observe significant better response rates in patients with irAEs (n = 17), although we saw a slight trend of a better mOS and mPFS in this subgroup of patients. Further validation in larger patient cohorts and prospective trials is certainly needed.

The main limitation of the presented study is its retrospective design. Treatment was applied and response was assessed by local standards of each center and short follow‐up might further underestimate rates of adverse events.

In conclusion, we confirm that immuno‐chemotherapy treatment for BTC followed by durvalumab maintenance is feasible, safe and effective in patients under real‐life clinical management. However, patients with a reduced performance status and/or gall bladder cancer had a significantly worse outcome. Differential outcome might depend on the genomic background of CCAs and warrants further investigations in larger patient cohorts with prospective designs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Acquisition of data (acquired and managed patients): All authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: Katharina Mitzlaff, Carolin Zimpel, Martha M. Kirstein, Jens U. Marquardt. Writing the manuscript: Katharina Mitzlaff, Carolin Zimpel, Martha M. Kirstein, Jens U. Marquardt. All authors discussed the results and critically commented on the manuscript. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

CZ reports participation in the advisory boards and lecture fees from AstraZeneca and travel expenses from Roche. JUM received honoraria from Roche, AstraZeneca, Ipsen, Eisai, MSD. PS received honoraria from Incyte, Eisai, BMS and MSD. KS received advisory and consulting fees from MSD and AstraZeneca as well as lecture fees from AstraZeneca. F. F. has received travel support from Ipsen, Abbvie, Astra Zeneca and speaker's fees from AbbVie, MSD, Ipsen and Astra Zeneca. MQ received advisory boards and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, BMS, MSD, Amgen, Takeda, Astella and Roche. MTD reports travel expenses covered by AstraZeneca and KM reports travel expenses covered by Roche and Ipsen.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was approved by the local ethics committee as well as the ethics committees (AZ 2023‐532) of the individual centers for retrospective analyses of clinical data.

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is a project of the German Alliance for Liver Cancer (GALC). This study was supported by internal funding from the Department of Medicine 1, UKSH Campus Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Mitzlaff K, Kirstein MM, Müller C, Venerito M, Olkus A, Dill MT, et al. Efficacy, safety and differential outcomes of immune‐chemotherapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin and durvalumab in patients with biliary tract cancers: a multicenter real world cohort. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12(9):1230–42. 10.1002/ueg2.12656

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bergquist A, von Seth E. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29(2):221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, Carioli G, Hashim D, Boffetta P, El‐Serag HB, et al. Global trends in mortality from intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2019;71(1):104–114. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Voesch S, Bitzer M, Blodt S, Follmann M, Freudenberger P, Langer T, et al. S3‐Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie des hepatozellularen Karzinoms und biliarer Karzinome—Version 2.0—Juni 2021, AWMF‐Registernummer: 032‐053OL. Z Gastroenterol. 2022;60(1):e131–e185. 10.1055/a-1589-7585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1273–1281. 10.1056/nejmoa0908721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shroff RT, Guthrie KA, Scott AJ, Borad MJ, Goff LW, Matin K, et al. SWOG 1815: a phase III randomized trial of gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab‐paclitaxel versus gemcitabine and cisplatin in newly diagnosed, advanced biliary tract cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(4_Suppl l):LBA490–LBA. 10.1200/jco.2023.41.4_suppl.lba490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phelip JM, Desrame J, Edeline J, Barbier E, Terrebonne E, Michel P, et al. Modified FOLFIRINOX versus CISGEM chemotherapy for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (PRODIGE 38 AMEBICA): a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(3):262–271. 10.1200/jco.21.00679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oh DY, Ruth He A, Qin S, Chen LT, Okusaka T, Vogel A, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;1(8):EVIDoa2200015. 10.1056/evidoa2200015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rimini M, Fornaro L, Lonardi S, Niger M, Lavacchi D, Pressiani T, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer: an early exploratory analysis of real‐world data. Liver Int. 2023;43(8):1803–1812. 10.1111/liv.15641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olkus A, Tomczak A, Berger AK, Rauber C, Puchas P, Wehling C, et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer: an exploratory analysis of real‐world data. Target Oncol. 2024;19(2):213–221. 10.1007/s11523-024-01044-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castelo‐Branco L, Pellat A, Martins‐Branco D, Valachis A, Derksen JWG, Suijkerbuijk KPM, et al. ESMO guidance for reporting Oncology real‐world evidence (GROW). Ann Oncol. 2023;34(12):1097–1112. 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelley RK, Ueno M, Yoo C, Finn RS, Furuse J, Ren Z, et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (KEYNOTE‐966): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10391):1853–1865. 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00727-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goyal L, Meric‐Bernstam F, Hollebecque A, Valle JW, Morizane C, Karasic TB, et al. Futibatinib for FGFR2‐rearranged intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(3):228–239. 10.1056/nejmoa2206834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abou‐Alfa GK, Macarulla T, Javle MM, Kelley RK, Lubner SJ, Adeva J, et al. Ivosidenib in IDH1‐mutant, chemotherapy‐refractory cholangiocarcinoma (ClarIDHy): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):796–807. 10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30157-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abou‐Alfa GK, Sahai V, Hollebecque A, Vaccaro G, Melisi D, Al‐Rajabi R, et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open‐label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):671–684. 10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30109-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lagenfelt H, Blomstrand H, Elander NO. Real‐world evidence on palliative gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GemOx) combination chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(14):3507. 10.3390/cancers13143507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Personeni N, Lleo A, Pressiani T, Colapietro F, Openshaw MR, Stavraka C, et al. Biliary tract cancers: molecular heterogeneity and new treatment options. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(11):3370. 10.3390/cancers12113370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Czauderna C, Kirstein MM, Tews HC, Vogel A, Marquardt JU. Molecular subtypes and precision Oncology in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):2803. 10.3390/jcm10132803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gehl V, O'Rourke CJ, Andersen JB. Immunogenomics of cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Budhu A, Pehrsson EC, He A, Goyal L, Kelley RK, Dang H, et al. Tumor biology and immune infiltration define primary liver cancer subsets linked to overall survival after immunotherapy. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4(6):101052. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen X, Wang D, Liu J, Qiu J, Zhou J, Ying J, et al. Genomic alterations in biliary tract cancer predict prognosis and immunotherapy outcomes. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(11):e003214. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rimini M, Loi E, Rizzato MD, Pressiani T, Vivaldi C, Gusmaroli E, et al. Different genomic clusters impact on responses in advanced biliary tract cancer treated with cisplatin plus gemcitabine plus durvalumab. Target Oncol. 2024;19(2):223–235. 10.1007/s11523-024-01032-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez‐Olivo MA, Kachira JJ, Abdel‐Wahab N, Pundole X, Aldrich JD, Carey P, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies and uncontrolled trials reporting on the use of checkpoint blockers in patients with cancer and pre‐existing autoimmune disease. Eur J Cancer. 2024;207:114148. 10.1016/j.ejca.2024.114148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verheijden RJ, van Eijs MJM, May AM, van Wijk F, Suijkerbuijk KPM. Immunosuppression for immune‐related adverse events during checkpoint inhibition: an intricate balance. npj Precis Oncol. 2023;7(1):41. 10.1038/s41698-023-00380-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Das S, Johnson DB. Immune‐related adverse events and anti‐tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):306. 10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y, Wang X, Li Y, Hong Y, Zhao Q, Ye Z. Immune‐related adverse events correlate with the efficacy of PD‐1 inhibitors combination therapy in advanced cholangiocarcinoma patients: a retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1141148. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1141148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lau G, Cheng A.‐L, Sangro B, Kudo M, Kelley RK, Tak WY, et al. Outcomes by occurrence of immune‐mediated adverse events (imAEs) with tremelimumab (T) plus durvalumab (D) in the phase 3 HIMALAYA study in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16_Suppl l):4004. 10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.4004 37207300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.