Abstract

Background

The Skeletal Muscle Index (SMI) serves as an objective metric for assessing nutritional status in patients with malignant tumors. Research has found baseline nutritional status can influence both the efficacy and prognosis of targeted anti-tumor therapies, with growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors frequently inducing drug-related sarcopenia. Fruquintinib has received approval for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. This study examines the prognostic significance of baseline SMI in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer undergoing treatment with fruquintinib. Additionally, the study investigates the incidence of SMI reduction following fruquintinib therapy to assess its impact on patient prognosis.

Methods

A retrospective multicenter study was conducted to analyze patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who received fruquintinib treatment across eight medical centers in Eastern China. The muscle area at the third lumbar vertebra was assessed, and both baseline and post-treatment SMI values were calculated independently. The relationship between SMI and patient survival was subsequently examined.

Results

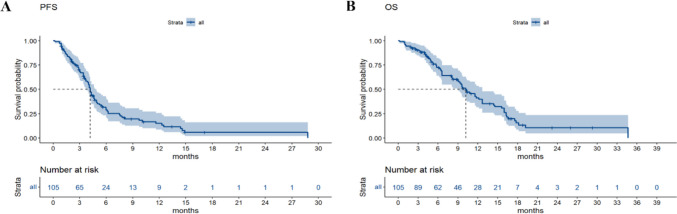

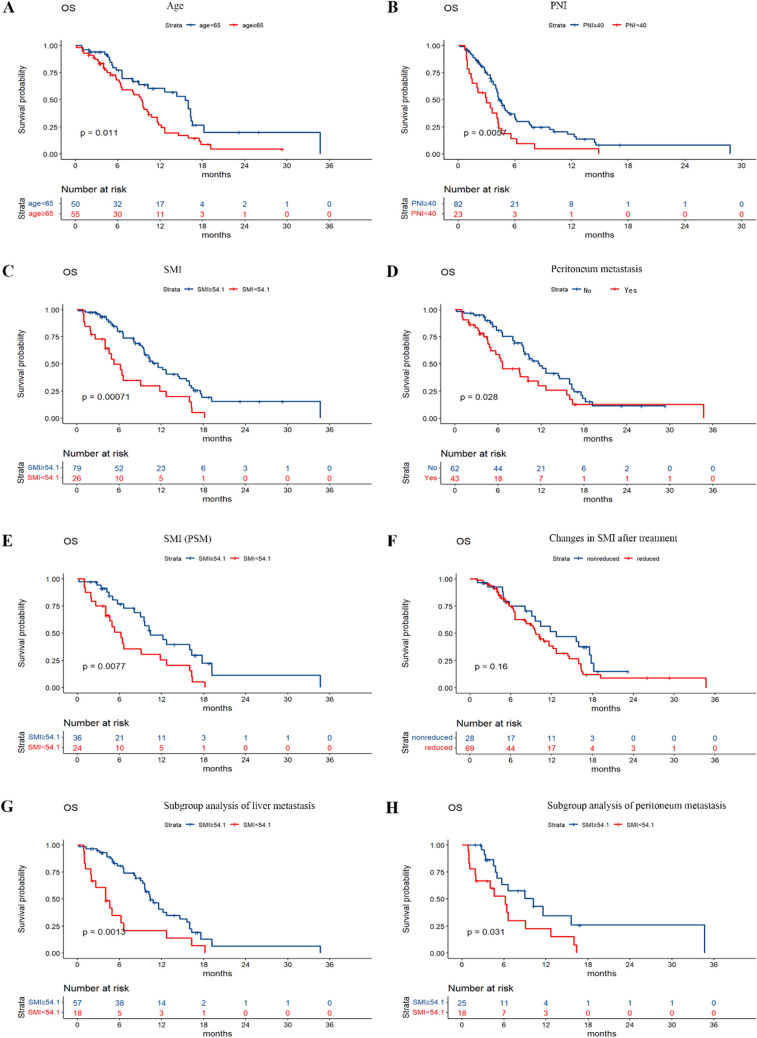

The median progression-free survival (PFS) for the cohort of 105 patients was 4.2 months (95% CI, 3.7 to 4.9 months), while the median overall survival (OS) was 10.2 months (95% CI, 9.0 to 12.7 months). Notably, the baseline SMI prior to the initiation of fruquintinib therapy exhibited a significant correlation with OS (P = 0.0077). Multivariate analysis indicated that baseline SMI serves as an independent prognostic factor for OS (P = 0.005). Furthermore, after Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analysis, there was still a significant correlation between baseline SMI and OS. Among the patients, 28.87% developed sarcopenia following oral administration of fruquintinib. However, no statistically significant difference in OS was observed between the group with reduced SMI and the group without SMI reduction after treatment with fruquintinib.

Conclusion

The baseline SMI was identified as an independent prognostic factor for OS and may influence the survival outcomes of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer undergoing treatment with fruquintinib. Despite the potential of fruquintinib to induce sarcopenia, no significant correlation was observed between changes in SMI following treatment and patient survival.

Keywords: Fruquintinib, Skeletal muscle index, Metastatic colorectal cancer, Sarcopenia

Colorectal cancer represents one of the most prevalent forms of gastrointestinal neoplasms. Patients diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer typically progress to third-line treatment following initial chemotherapy and targeted therapy. The optimization of third-line therapeutic strategies is crucial for enhancing quality of life, survival rates, and overall prognosis [1–3]. Following multiple systemic front-line treatments, patients with advanced-stage disease exhibit a marked decline in physical condition and nutritional status compared to their state at initial diagnosis, with an increased incidence of malnutrition and diminished performance status. Malnutrition frequently occurs in patients with advanced malignant tumors, often culminating in cachexia. Cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome characterized by sarcopenia with or without loss of adipose tissue and progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass [4]. Sarcopenia is characterized by a progressive and widespread decline in skeletal muscle mass and strength, which may result in functional impairment, prolonged hospitalization, heightened susceptibility to infections, and diminished survival rates among cancer patients [5]. In the advanced stages of tumor progression, sarcopenia may arise not only as a direct consequence of the disease but also as a result of chemotherapy and other therapeutic interventions. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have emerged as widely utilized therapeutic agents in the treatment of various cancers. Clinical studies with limited sample sizes have indicated that TKIs such as sorafenib, regorafenib, sunitinib, and lenvatinib may contribute to muscle loss and exacerbate muscle atrophy in patients with advanced-stage disease [6–10]. Tyrosine kinases are enzymes that play a critical role in the regulation of numerous normal cellular processes by targeting specific proteins [11, 12]. Fruquintinib, a highly selective antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor, can prolong the survival time of patients with advanced colorectal cancer [13, 14]. As one of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors, can fruquintinib also cause sarcopenia like other TKIs? This study investigates whether a lower baseline SMI prior to treatment correlates with poorer survival outcomes in patients treated with fruquintinib.

Patients

This was a retrospective observational analysis of 105 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who received fruquintinib at eight medical centers in Eastern China from January 2019 to December 2023. All patients had a histopathological diagnosis of colorectal cancer and underwent peritoneum CT scans prior to receiving fruquintinib. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinyi Medical Group.

Inclusion criteria

Progression after receiving at least two prior treatment regimens containing oxaliplatin and irinotecan; a minimum of two months of fruquintinib treatment; no history of serious cardiac, hepatic, renal or other underlying diseases; absence of severe complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding or obstruction; no uncontrolled hypertension; and no restrictions on food access or intake.

Methods

Fruquintinib was prescribed at a dosage of 5 mg orally once daily for a period of three weeks, followed by a one-week rest interval. All participants underwent peritoneal computed tomography (CT) scans within one week before the initiation of treatment and two months post-treatment to assess the area of skeletal muscle (SMA) at the third lumbar vertebra (L3) level. An peritoneum CT scan was performed with a thickness of 5 mm, and the CT scan was located in the plane of the lumbar 3 vertebral body. The area of all peritoneum muscles with CT Hounsfield unit (Hu) tissue thresholds ranging from -29 Hu to 150 Hu was calculated by subtracting the area of nonskeletal muscles in the peritoneum cavity to obtain the SMAs of 7 muscle groups (psoas major, erector spine, lumbar peritoneum muscles, transverse abdominis, external oblique and rectus abdominis) [15]. The skeletal muscle index (SMI, SMI = SMA/body surface area) was calculated [16]. The cutoff value for sarcopenia was defined as an SMI < 54.1 cm2/m2, which was calculated by Xtile version 3.6 (https://x-tile.software.informer.com/).

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), body mass index (BMI), hemoglobin (Hb), serum albumin (ALB), lymphocyte count, Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS2002) and Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) nutritional scores were monitored before treatment and 2 months after treatment. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) was calculated. PNI = serum albumin (g/L) + 5 × total number of peripheral blood lymphocytes (× 109/L) [17].

The efficacy of fruquintinib treatment was assessed using the RECIST criteria version 1.1, categorizing outcomes as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) [18]. The objective response rate (ORR) was determined as the proportion of patients exhibiting CR or PR following fruquintinib administration. Similarly, the disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of patients demonstrating CR, PR, or SD post-treatment. All patients were followed up, and progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were recorded. PFS was calculated as the time from treatment with fruquintinib to tumor progression, and OS was calculated as the time from treatment with fruquintinib to death or the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version 4.3.2 (http://www.r-project.org/). Survival analysis was plotted on Kaplan–Meier curves, and hazard ratios were calculated using Cox regression analysis. A P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2019 and December 2023, a cohort of 105 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer underwent treatment with fruquintinib. The cohort comprised 71 male and 34 female patients, with ages ranging from 43 to 79 years and a median age of 65 years. The PG-SGA nutritional scores varied from 1 to 8 points. The PNI values ranged from 23.05 to 63.35, with a median value of 44.45. Tumor localization among the patients was as follows: 29 patients had tumors in the ascending colon, 4 in the transverse colon, 8 in the descending colon, 15 in the sigmoid colon, and 49 in the rectum. Additionally, liver metastasis was observed in 75 patients, while lung metastasis was present in 58 patients.

Changes in skeletal muscle mass index

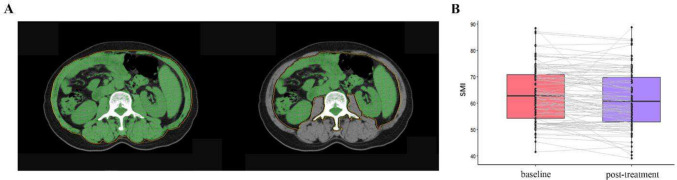

At baseline, all patients exhibited a SMI ranging from 41.40 to 88.36 cm2/m2, as determined by CT imaging at the L3 vertebral level in a representative colorectal cancer patient, illustrated in Fig. 1A. The median SMI was 62.88 cm2/m2. Of the cohort, 26 out of 105 patients (24.76%) were diagnosed with sarcopenia. Figure 1B depicts the alterations in SMI for each patient following two cycles of fruquintinib treatment. Post-treatment, 69 out of 97 patients (71.13%) exhibited a reduction in SMI, with the median SMI declining by 2.27 cm2/m2 to 60.61 cm2/m2. Additionally, 28 out of 97 patients (28.87%) developed sarcopenia.

Fig. 1.

A SMA based on CT images at the level of the third lumbar vertebra. B Changes in SMI of each patient after treatment

SMI and clinical features

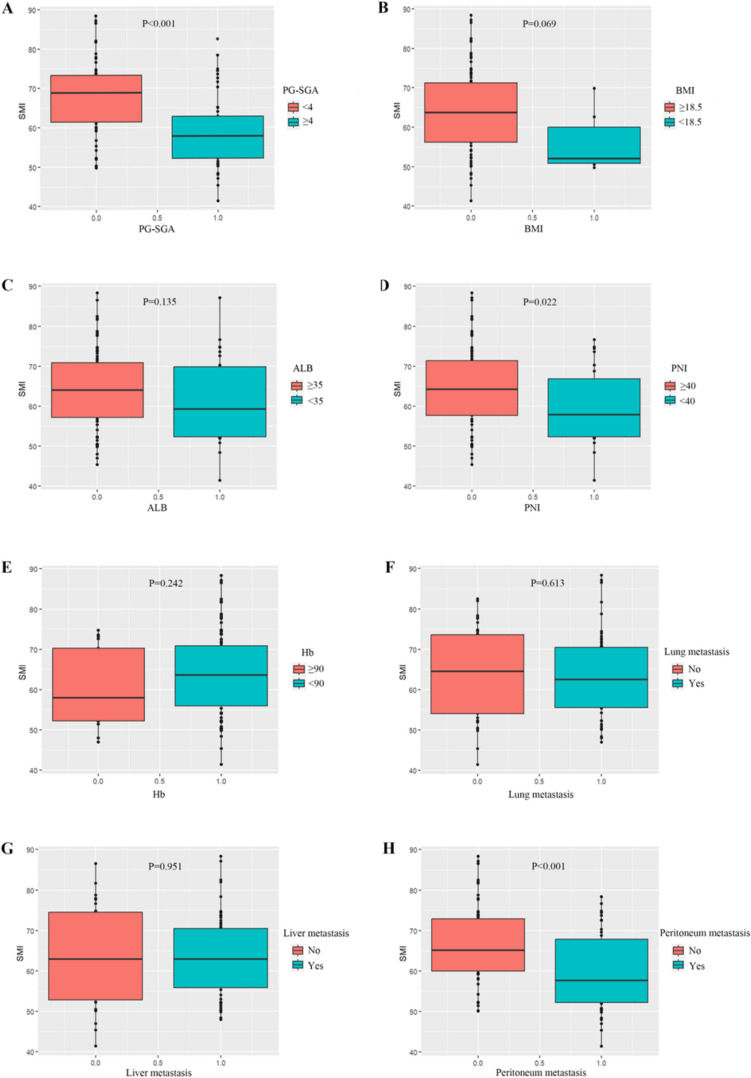

The baseline SMI of patients demonstrated a positive correlation with the PNI and the PG-SGA, while showing a negative correlation with the presence of peritoneal metastasis (Table 1). Specifically, patients with a PG-SGA score below 4, a PNI of 40 or above, and an absence of peritoneal metastasis exhibited higher baseline SMI compared to those with a PG-SGA score of 4 or above, a PNI below 40, or the presence of peritoneal metastasis (Fig. 2A, D, H). However, no significant correlations were observed between baseline SMI and BMI, ALB, Hb, the presence of lung or liver metastasis (Fig. 2B, C, E, F, G).

Table 1.

Basic clinical features of the patients according to the baseline SMI

| Clinical features | SMI high n(%) |

SMI low n(%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.957 | ||

| < 65 | 37(46.8) | 13(50.0) | |

| ≥ 65 | 42(53.2) | 13(50.0) | |

| Gender | 0.137 | ||

| Male | 57 (72.2) | 14(53.8) | |

| Female | 22(27.8) | 12(46.2) | |

| PG-SGA | 0.001 | ||

| < 4 | 53(67.1) | 7(26.9) | |

| ≥ 4 | 26(32.9) | 19(73.1) | |

| PNI* | 0.038 | ||

| ≥ 40 | 66(83.5) | 16(61.5) | |

| < 40 | 13(16.5) | 10(38.5) | |

| Primary tumor location | 0.211 | ||

| Rectum | 32(40.5) | 17(65.4) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 13(16.5) | 2(7.7) | |

| Descending colon | 6(7.6) | 2(7.7) | |

| Transverse colon | 4(5.1) | 0(0) | |

| Ascending colon | 24(30.3) | 5(19.2) | |

| Primary tumor resection | 0.379 | ||

| No | 8(10.1) | 5(19.2) | |

| Yes | 71(89.9) | 21(80.8) | |

| Liver metastasis | 0.971 | ||

| No | 22(27.8) | 8(30.8) | |

| Yes | 57 (72.2) | 18(69.2) | |

| Lung metastasis | 0.695 | ||

| No | 34(43.0) | 13(50.0) | |

| Yes | 45(57.0) | 13(50.0) | |

| Peritoneum metastasis | 0.002 | ||

| No | 54(68.4) | 8(30.8) | |

| Yes | 25(31.6) | 18(69.2) | |

| KRAS | 0.394 | ||

| Wild | 40(50.6) | 10(38.5) | |

| Mutation | 39(49.4) | 16(61.5) |

*PNI: Prognostic nutritional index

Fig. 2.

A-H Correlation between the baseline SMI and clinical factors

SMI and therapeutic response to fruquintinib

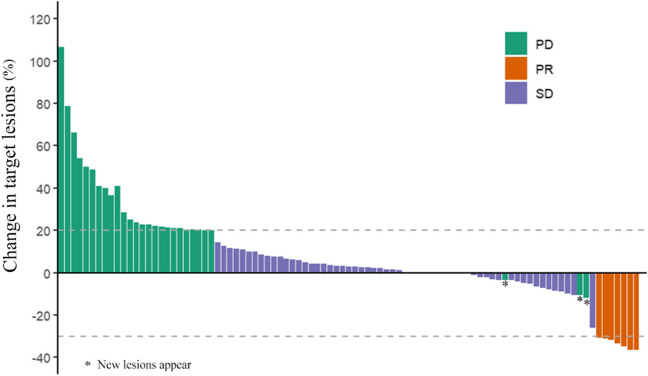

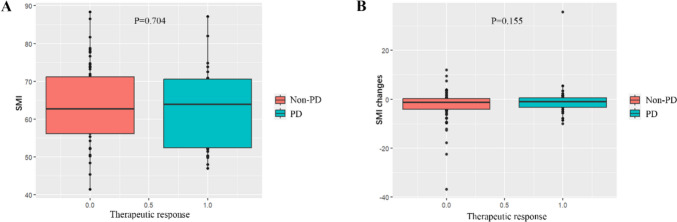

Among the patient cohort, PR was observed in 8 individuals, SD was noted in 61 individuals, and PD was evident in 34 individuals. Notably, no patients exhibited a CR. The ORR was calculated to be 7.62%, while the DCR was 65.71%. Figure 3 illustrates a waterfall plot depicting the best therapeutic response for the target lesions. Analysis revealed no significant correlation between the baseline SMI and the therapeutic response to fruquintinib, as shown in Fig. 4A. Similarly, no significant correlation was found between changes in SMI and the efficacy of fruquintinib following two cycles of treatment, as depicted in Fig. 4B.

Fig. 3.

Waterfall plot of optimal therapeutic effects

Fig. 4.

A-B Correlation between SMI and the therapeutic response to fruquintinib

Survival analysis

The median PFS of the 105 patients was 4.2 months (95% CI, 3.7 to 4.9 months), and the median OS was 10.2 months (95% CI, 9.0 to 12.7 months) (Fig. 5). A significant association was observed between OS and variables such as age, baseline SMI, baseline PNI, and the presence of peritoneal metastasis (Fig. 6A, B, C, and D). Further multivariate analysis identified age, baseline SMI, and baseline PNI as independent prognostic factors for OS, with statistical significance (P = 0.005, P = 0.003, and P = 0.006, respectively) (Table 2). Patients of advanced age, as well as those with lower baseline PNI and SMI, exhibited reduced survival rates. Given the imbalance in PG-SGA, PNI, and peritoneal metastasis among the patients included in the study, a PSM analysis was conducted. The results indicated that even after controlling for these confounding factors, a significant difference in survival persisted between patients with low baseline SMI and those with normal baseline SMI (P = 0.0077) (Fig. 6E). However, no significant difference in OS was observed between the reduced-SMI group and the non-reduced-SMI group following treatment with fruquintinib (Fig. 6F). This study found that changes in SMI after fruquintinib therapy were not significantly correlated with OS. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences in OS were observed based on sex, PG-SGA score, primary tumor location, radical resection of colorectal cancer, liver metastasis status, lung metastasis status, or KRAS status, with P-values of 0.3, 0.05, 0.19, 0.89, 0.05, 0.11, and 0.28, respectively. Subgroup analysis indicated that among patients with liver and peritoneal metastases, those with a low baseline SMI exhibited a shorter survival duration (Fig. 6G, H).

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS (A) and OS (B) for full cohort

Fig. 6.

A-H Kaplan–Meier curves of OS based on significant clinical factors

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for OS

| Variable | median OS(m)(95%CI) |

Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR(95%CI) | P-value | HR(95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| < 65 | 15.6(10.3–16.6) | 1 | - | ||

| ≥ 65 | 9.5(6.5–11.6) | 1.87(1.14–3.06) | 0.013 | 2.05(1.24–3.41) | 0.005 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 9.6(8.1–12.2) | 1 | - | ||

| Female | 12.7(6.6-NA) | 0.75(0.44–1.28) | 0.292 | - | - |

| PG-SGA | |||||

| < 4 | 10.8(9.5–16.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 4 | 9.1(5.0–12.7) | 1.61(1.00–2.60) | 0.051 | 1.01(0.60–1.71) | 0.975 |

| PNI | |||||

| ≥ 40 | 11.8(9.7–15.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| < 40 | 6.2(4.6–10.2) | 2.74 (1.57–4.77) | < 0.001 | 2.52(1.38–4.58) | 0.003 |

| SMI | |||||

| ≥ 54.1 | 11.6(9.6–15.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| < 54.1 | 5.3(4.0–12.7) | 2.37 (1.42–3.95) | 0.001 | 2.26(1.26–4.05) | 0.006 |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Left colon | 9.3(6.6–12.7) | 1 | - | ||

| Right colon | 12.7(9.6-NA) | 0.70 (0.41–1.19) | 0.184 | - | - |

| Proctocolectomy | |||||

| No | 11.6(9.5-NA) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 9.7(8.1–12.7) | 0.96(0.47–1.94) | 0.905 | - | - |

| Liver metastasis | |||||

| No | 12.7(9.1-NA) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 9.7(8.1–12.2) | 1.73(0.99–3.02) | 0.053 | - | - |

| Lung metastasis | |||||

| No | 9.5(6.2–12.7) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 11.8(9.3–16.0) | 0.68(0.42–1.09) | 0.108 | - | - |

| Peritoneum metastasis | |||||

| No | 11.8(9.6–16.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 6.6(5.0–12.7) | 1.72 (1.05–2.81) | 0.031 | 1.22(0.69–2.15) | 0.488 |

| KRAS | |||||

| Wild | 9.1(6.6–11.6) | 1 | - | ||

| Mutation | 12.7(9.6–16.3) | 0.77(0.47–1.24) | 0.279 | - | - |

Discussion

Research has shown that 35% of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receive third-line treatment [19]. Currently, the main drugs used for the third-line treatment of colorectal cancer in China are trifluuridine tetrapyrimidine (TAS-102), regofinib and fruquintinib [20]. Antivascular therapy is a commonly used treatment strategy and a very promising treatment method for advanced tumors. Fruquintinib, an anti-vascular tyrosine kinase inhibitor that acts on vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR-1), VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3, is an optional drug for the third-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Both the FRESCO and FRESCO2 studies have confirmed that compared to placebo, fruquintinib can significantly prolong the OS and PFS of metastatic colorectal cancer patients as a third-line treatment [13, 14]. In our retrospective study, the median OS of 105 patients was 10.2 months, and the median PFS was 4.2 months, demonstrating similar efficacy to that of the FRESCO study. Our study validated the value of fruquintinib in the third-line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer.

In recent years, the impact of skeletal muscle loss during antitumor treatment on clinical outcomes has been a focus of attention. Generally, compared to cancer patients without sarcopenia, cancer patients with sarcopenia have poorer survival [21–23]. And the occurrence of sarcopenia is associated with a heightened incidence of complications during the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors [24–26]. Patients with upper gastrointestinal tumors and pelvic tumors also have a greater incidence of sarcopenia [27–30]. Multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been shown to prolong the survival time of advanced cancer patients. While treating tumors, studies have shown that some antivascular TKIs, such as sorafenib, regorafenib, sunitinib and lenvatinib, induce a decrease in skeletal muscle mass [6–10]. However, not all anti-vascular TKIs lead to sarcopenia. There are very few TKIs that have not been found to cause sarcopenia, such as pezopanib. Sunitinib can cause muscle loss in renal cancer patients, while pezopanib, another commonly used TKI for advanced renal cancer, does not cause muscle loss in renal cancer patients [31]. Therefore, what happens after treatment with a relatively new antivascular targeted drug, fruquintinib?

We retrospectively investigated the SMI of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who received treatment with fruquintinib in multiple medical centers. CT images were utilized to assess the SMA at the L3 vertebral level, and subsequently, the SMI was calculated. The associations between the SMI and various clinical factors were then examined. Following treatment with fruquintinib, 71.13% of patients with colorectal cancer exhibited a reduction in SMI, and the prevalence of sarcopenia increased from 24.76% to 28.87%. Prior to fruquintinib treatment, the baseline SMI was lower, and patients frequently presented with a reduced PNI and poorer scores on the PG-SGA. Our data suggest that patients with peritoneal metastases exhibit a reduced SMI in comparison to those without peritoneal metastases. This phenomenon may be attributed to gastrointestinal dysfunction and associated disorders in digestion and absorption, which consequently result in compromised nutrient intake. Univariate analysis revealed that age, baseline SMI, baseline PNI, and peritoneum metastasis were significantly associated with OS. Further multivariate analysis suggested that age, baseline SMI, and baseline PNI were independent prognostic factors. The value of skeletal muscle loss in the survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer has been evaluated and analyzed [23, 32–36]. Research has shown that those with lower SMI in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer have a higher risk of death compared to those without sarcopenia [23, 32–34]. Sarcopenia was found to be significantly correlated with a poorer prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer, aligning with our current research findings. Nonetheless, the study revealed no difference in survival outcomes based on post-treatment reductions in SMI following administration of fruquintinib. This suggests that the initial muscle loss is a determinant of reduced survival, rather than a consequence of fruquintinib-induced muscle depletion.

Why do TKIs cause muscle loss? What is the underlying mechanism? There is little exploration on this issue, and in-depth research is necessary. A study showed that imatinib, sunitinib and sorafenib inhibited the activity of mitochondrial complexes and glucose and nucleoside uptake, leading to decreased energy production and mitochondrial function in a skeletal muscle cell model [37]. Sorafenib might decrease serum carnitine levels by inhibiting the absorption of carnitine, thereby inducing presarcopenia [38]. In many cancers, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is overactive, reducing cell apoptosis and allowing cell proliferation. TKI drugs ultimately block the activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway by targeting different factors, thereby achieving the therapeutic effect of inhibiting tumor cell proliferation. The preservation of skeletal muscle mass is contingent upon a precise equilibrium between protein synthesis and protein degradation. In individuals with normal physiological function, the activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway facilitates muscle hypertrophy, regulates the size of skeletal muscle fibers, and prevents muscle atrophy [39]. Conversely, TKIs impede muscle hypertrophy, promote atrophy, and suppress protein synthesis, thereby contributing to the development of sarcopenia [40]. The inhibition of the mTOR pathway is mediated through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by interleukin-6 (IL-6) in C2C12 myoblasts [41]. This suggests that a reduction in the anabolic mTOR complex 1 activity in skeletal muscle contributes to muscle mass loss.

As this investigation was retrospective and involved a relatively small cohort of patients, the findings may not comprehensively represent the actual scenario. This study encompassed colorectal cancer patients undergoing three or more lines of treatment. To mitigate the potential confounding effect of the number of treatment lines, future clinical study should focus on colorectal cancer patients with the same number of treatment lines. Additionally, as a retrospective study, we were unable to ascertain the intake of enteral nutrition, particularly protein, for each patient during the treatment period, which might influence SMI changes. Future research should incorporate larger sample sizes and employ rigorous study designs to substantiate our conclusions.

Conclusion

Patients undergoing treatment with fruquintinib for metastatic colorectal cancer may experience muscle loss, with baseline SMI prior to treatment influencing patient survival. However, although fruquintinib may induce muscle loss, it does not currently appear to impact patient survival. Consequently, fruquintinib-induced sarcopenia cannot be considered a prognostic indicator for patient outcomes. We should pay more attention to the nutritional status of patients before they receive fruquintinib treatment in clinical practice.

Author contribution

Wanfen Tang: Practical performance, Investigation, Data analysis, Formal analysis, Preparation manuscript, Funding acquisition Fakai Li: Practical performance, Investigation Hongjuan Zheng: Data analysis, Investigation Jinglei Zhao: Practical performance, Investigation Hangping Wei: Practical performance, Investigation Xuerong Xiong: Practical performance, Investigation Hailang Chen: Practical performance, Investigation Cui Zhang: Practical performance, Investigation Weili Xie: Practical performance, Investigation Penghai Zhang: Practical performance, Investigation Guangrong Gong: Image analysis Mingliang Ying: Image analysis, Funding acquisition Qiusheng Guo: Data curation Qinghua Wang: Supervision Jianfei Fu: Design study, Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Science and Technology Bureau of Jinhua City (grant number 2021–3-080, 2020–3-028).

This study was supported by grants from Department of Health of Zhejiang Province (grant number 2022KY1330).

This study was supported by grants from Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (grant number JY2020-2–04).

Data availability

The original data can be provided with supplementary information files.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nevala-Plagemann C, Sama S, Ying J et al (2023) A real-world comparison of Regorafenib and Trifluridine/Tipiracil in Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in the United States. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 21(3):257–264. 10.6004/jnccn.2022.7082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitale P, Zanaletti N, Famiglietti V et al (2021) Retrospective study of Regorafenib Versus TAS-102 efficacy and safety in Chemorefractory metastatic colorectal Cancer (mCRC) patients: a multi-institution Real Life Clinical Data. Clin Colorectal Cancer 20(3):227–235. 10.1016/j.clcc.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao KY, Chen HP, Rau KM et al (2024) Association between sidedness and survival among chemotherapy refractory metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with trifluridine/tipiracil or regorafenib. Oncologist 7:oyae235. 10.1093/oncolo/oyae235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD et al (2011) Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 12(5):489–495. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni J, Zhang L (2020) Cancer Cachexia: Definition, Staging, and Emerging Treatments. Cancer Manag Res 12:5597–5605. 10.2147/CMAR.S261585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Antoun S, Baracos VE, Birdsell L et al (2010) Low body mass index and sarcopenia associated with dose-limiting toxicity of sorafenib in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 21(8):1594–1598. 10.1093/annonc/mdp605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huemer F, Schlintl V, Hecht S et al (2019) Regorafenib is Associated with increased skeletal muscle loss compared to TAS-102 in metastatic colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 18(2):159-166e3. 10.1016/j.clcc.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu W, Wu J, Liu X et al (2017) Early skeletal muscle loss during target therapy is a prognostic biomarker in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. Sci Rep 7(1):7587. 10.1038/s41598-017-07955-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kariyama K et al (2019) Clinical features of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions: Multicenter analysis. Cancer Med 8(1):137–146. 10.1002/cam4.1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chéry L, Borregales LD, Fellman B et al (2017) The effects of Neoa djuvant axitinib on anthropometric parameters in patients with locally advanced non-metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 108:114–121. 10.1016/j.urology.2017.05.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora A, Scholar EM (2005) Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315(3):971–979. 10.1124/jpet.105.084145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawson T (2002) Regulation and targets of receptor tyrosine kinases. Eur J Cancer 38(Suppl 5):S3-10. 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)80597-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Qin S, Xu RH et al (2018) Effect of Fruquintinib vs Placebo on overall survival in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal Cancer: the FRESCO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 319(24):2486–2496. 10.1001/jama.2018.7855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasari A, Sobrero A, Yao J et al (2021) FRESCO-2: a global phase III study investigating the efficacy and safety of fruquintinib in metastatic colorectal cancer. Future Oncol 17(24):3151–3162. 10.2217/fon-2021-0202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB et al (1998) Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 85(1):115–122. 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barret M, Antoun S, Dalban C et al (2014) Sarcopenia is linked to treatment toxicity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Nutr Cancer 66(4):583–589. 10.1080/01635581.2014.894103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jian-Hui C, Iskandar EA, Cai SI et al (2016) Significance of Onodera’s prognostic nutritional index in patients with colorectal cancer: a large cohort study in a single Chinese institution. Tumour Biol 37(3):3277–3283. 10.1007/s13277-015-4008-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45(2):228–247. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trotti A, Bellm LA, Epstein JB et al (2003) Mucositis incidence, severity and associated outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. Radiother Oncol 66(3):253–262. 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00404-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossberg AJ, Chamchod S, Fuller CD et al (2016) Association of Body Composition with Survival and Locoregional Control of Radiotherapy-Treated Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2(6):782–789. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Versteeg KS, de van der Schueren MA, den Braver NR, Berkhof J, Langius JA, Verheul HM (2016) Loss of muscle Mass during Chemotherapy is predictive for poor survival of patients with metastatic colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34(12):1339–1344. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lilong Z, Kuang T, Li M, Li X, Hu P, Deng W, Wang W (2024) Sarcopenia affects the clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Clin Nutr 43(1):31–41. 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shachar SS, Williams GR, Muss HB et al (2016) Prognostic value of Sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur J Cancer 57:58–67. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Chen Y, He J, Yin C, Xie M (2024) Sarcopenia predicts postoperative complications and survival of Colorectal Cancer patients undergoing radical surgery. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 85(9):1–17. 10.12968/hmed.2024.0297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagarajan G, Doshi P, Bardeskar NS, Kulkarni A, Punamiya A, Tongaonkar H (2023) Association between Sarcopenia and postoperative complications in patients undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal or hepato-pancreatico-biliary cancer. J Surg Oncol 128(4):682–691. 10.1002/jso.27315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simonsen C, de Heer P, Bjerre ED, Suetta C, Hojman P, Pedersen BK, Svendsen LB, Christensen JF (2018) Sarcopenia and Postoperative Complication Risk in Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology: a Meta-analysis. Ann Surg 268(1):58–69. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma DW, Cho Y, Jeon MJ et al (2019) Relationship between Sarcopenia and Prognosis in Patient with Concurrent Chemo-Radiation Therapy for Esophageal Cancer. Front Oncol 9:366. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung E, Lee HS, Cho ES et al (2020) Prognostic significance of Sarcopenia and skeletal muscle mass change during preoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Clin Nutr 39(3):820–828 Epub 2019 Mar 19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Psutka SP, Carrasco A, Schmit GD, Moynagh MR, Boorjian SA, Frank I, Stewart SB, Thapa P, Tarrell RF, Cheville JC, Tollefson MK (2014) Sarcopenia in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy: impact on cancer-specific and all-cause mortality. Cancer 120(18):2910–2918. 10.1002/cncr.28798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sánchez M, Castro-Eguiluz D, Luvián-Morales J et al (2019) Deterioration of nutritional status of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer during treatment with concomitant chemoradiotherapy. J Hum Nutr Diet 32(4):480–491. 10.1111/jhn.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Köstek O, Yılmaz E, Hacıoğlu MB et al (2019) Changes in skeletal muscle area and lean body mass during pazopanib vs sunitinib therapy for metastatic renal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 83(4):735–742. 10.1007/s00280-019-03779-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caan BJ, Meyerhardt JA, Kroenke CH et al (2017) Explaining the obesity Paradox: the Association between Body Composition and Colorectal Cancer Survival (C-SCANS Study). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26(7):1008–1015. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun G, Li Y, Peng Y et al (2018) Can Sarcopenia be a predictor of prognosis for patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 33(10):1419–1427. 10.1007/s00384-018-3128-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Vugt JL, Levolger S, Coelen RJ et al (2015) The impact of Sarcopenia on survival and complications in surgical oncology: A review of the current literature. J Surg Oncol 112(6):681–682. 10.1002/jso.24064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cespedes Feliciano E, Chen WY (2018) Clinical implications of low skeletal muscle mass in early-stage breast and colorectal cancer. Proc Nutr Soc 77(4):382–387. 10.1017/S0029665118000423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGovern J, Dolan RD, Horgan PG et al (2021) Computed tomography-defined low skeletal muscle index and density in cancer patients: observations from a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12(6):1408–1417. 10.1002/jcsm.12831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Damaraju VL, Kuzma M, Cass CE et al (2018) Multitargeted kinase inhibitors imatinib, sorafenib and sunitinib perturb energy metabolism and cause cytotoxicity to cultured C2C12 skeletal muscle derived myotubes. Biochem Pharmacol 155:162–171. 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amanuma M, Nagai H, Igarashi Y (2020) Sorafenib might induce Sarcopenia in patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma by inhibiting carnitine absorption. Anticancer Res 40(7):4173–4182. 10.21873/anticanres.14417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adnane L, Trail PA, Taylor I et al (2006) Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006, Nexavar), a dual-action inhibitor that targets RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in tumor cells and tyrosine kinases VEGFR/PDGFR in tumor vasculature. Methods Enzymol 407:597–612. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07047-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinninella E, Cintoni M, Raoul P et al (2020) Skeletal muscle loss during multikinase inhibitors therapy: Molecular pathways, clinical implications, and Nutritional challenges. Nutrients 12(10):3101. 10.3390/nu12103101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White JP, Puppa MJ, Gao S et al (2013) Muscle mTORC1 suppression by IL-6 during cancer cachexia: a role for AMPK. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304(10):E1042–E1052. 10.1152/ajpendo.00410.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data can be provided with supplementary information files.