Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to map the clinical pathway for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (AD) in a tertiary hospital to better understand patient needs and experiences, thereby suggesting improvements in patient-centered care.

Methods

A mixed-method approach was utilised involving a literature review, a questionnaire for healthcare professionals (HCPs), and two focus groups (one with HCPs and the other with patients with psoriasis or AD). Ethical approvals were obtained, and informed consent was acquired from all participants.

Results

Patients and HCPs identified significant delays in the pre-diagnosis phase, extending up to five years for psoriasis and three years for AD, adversely affecting the timely initiation of effective treatment. In addition, there were reported difficulties in obtaining appointments during flares, a lack of dermatologic emergencies, a need to increase human resources and physical space, and a need for telematic consultations for urgent cases. Discrepancies between HCPs’ perceptions and patients’ experiences highlighted unmet needs, particularly in primary care settings and emergency departments. Several strengths were also identified, including satisfactory experience in dermatology, the hospital’s high level of specialisation in the management of complex patients, optimal communication between services, consideration of patient preferences, and proper advice on hospital pharmacy care and administration support of treatment and adherence monitoring.

Conclusion

The findings underscore the necessity for interventions to reduce wait times and improve treatment immediacy and effectiveness post-diagnosis. The insights from this study can direct enhancements in patient management and satisfaction for individuals with psoriasis and AD.

Keywords: psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, care pathway, patient centered care

Plain Language Summary

This study looked into how patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (AD) are treated in a tertiary hospital. It focused on understanding the time it takes for patients to receive help and their satisfaction with the care received. By talking to doctors and patients, the researchers learned about the challenges in the early stages of these diseases and the delays in starting treatment or in the treatment process, among others. They discovered that these patients often wait too long before seeing a dermatologist, leading to a delay in treatment access. The study suggests that quicker diagnosis and treatment could improve how these conditions are managed and increase patient satisfaction.

Introduction

Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (AD) are common inflammatory skin diseases. Despite sharing some features, such as infiltration of immune cells and altered expression of proinflammatory cytokines,1 they are different clinical conditions.2,3 Psoriasis, with an estimated global prevalence of 1–3%, in its most common form, plaque psoriasis, is characterised by erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with coarse scale3,4 On the other hand, AD is a chronic, pruritic and inflammatory skin disease, which most commonly affects children (20%), but also affects adults (2,5%).5 Both conditions can also occur with flares and are associated with other comorbidities.6,7 Psoriasis is related to psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular disease, malignancies, diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, infections, and autoimmune disorders.8 Furthermore, AD is associated with allergic rhinitis, asthma and food allergy.9 Consequently, both psoriasis and AD, in addition to their associated comorbidities, can negatively impact patients’ quality of life (QoL) and psychological wellbeing.9,10

The current therapeutic strategies for the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis vary according to the severity of the disease. For patients with mild disease, topical treatments, including corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, are the first line of treatment.11,12 Emollients and moisturizers are crucial to maintain skin hydration and barrier function, especially in atopic dermatitis.13 Phototherapy is an effective option for patients with extensive psoriasis, using UVB or PUVA.4 For cases of moderate to high severity, systemic treatments such as methotrexate and cyclosporine are employed.14 Over the past two decades, the use of biologic drugs has emerged as an effective treatment modality, with treatments such as adalimumab, secukinumab and ustekinumab for psoriasis and dupilumab for atopic dermatitis demonstrating significant efficacy.4,12 These treatments are tailored to the needs of each patient, taking into consideration comorbidities and risk profiles.

The interaction between patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) is crucial for patient-centred care as it enables better health outcomes and, in turn, improves patients’ QoL.15 Furthermore, the design and execution of the different internal processes in healthcare centres can affect the general quality of patients care, their satisfaction and their health status.16,17 In this context, chronic pathologies such as psoriasis and AD are of particular relevance, as they are a frequent reason for consultation both in primary care and in hospital dermatology services.18

A qualitative methodology, which includes interviews with HCPs and patients, can assist in comprehending the care pathway and identifying areas for improvement. Interviews with HCPs can provide information on the operational aspects of the current care pathway and potential systemic challenges, while interviews with patients can capture personal experiences and perceptions, revealing gaps and barriers in the care pathway that may not be evident from a purely professional point of view. This dual perspective ensures a comprehensive understanding of the care pathway, which in turn allows for the identification of specific and feasible improvements.

Thus, we conducted a qualitative study in order to explore the care pathway of patients affected with psoriasis or AD and to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats from both HCPs and patients’ perspectives.

Methods

A scientific committee, consisting of three hospital pharmacists and three dermatologists, was involved in all phases of the project.

Study Design

The study took place in a tertiary hospital in Barcelona and comprised three phases: 1) a literature review to develop an ad-hoc questionnaire directed to HCPs; 2) an HCPs focus group; and 3) two focus group with patients.

The study protocol (coded as IIBSP-PDA-2022-106) was approved by the local ethics committee and it was developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.19,20 Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Questionnaire

Through the literature review, the research team developed a questionnaire for HCPs which comprised of 105 questions grouped in five categories: 1) pre-diagnosis and diagnosis, 2) treatment, 3) patient’s follow-up, 4) hospital pharmacy processes, and 5) general questions (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the entire process).

Patient Recruitment and Conducting the Focus Groups

Focus groups are based on the dynamics of interaction and discussion between participants. This methodology enables the collection of a broad range of perceptions, experiences, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes on a specific topic. The ideal number of participants is between 4 and 12.21,22 The content of the focus group was reported following the COREQ (Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative Research) guidelines.23 (Supplementary Table 1).

HCPs Focus Group

The focus group included members of the Scientific Committee (three dermatologists and three hospital pharmacists). Before the meeting, they had to complete an ad-hoc questionnaire. Its results permitted to map the care pathway for adults with psoriasis or AD which was further discussed and refined in the focus group with HCPs. The focus group session with HPCs was conducted by two members of the Outcomes’10 team and lasted approximately 2 hours (Supplementary Table 1).

Patient’s Focus Groups

A total of 22 patients (>18 years old) with moderate or severe psoriasis (n=11) and AD (n=11) were invited to participate in the study. Of those, 7 patients (5 women and 2 men) with psoriasis and 4 patients (3 women and 1 man) with AD consented to participate in the study. They were identified and invited to participate by the Scientific Committee. Visual thinking techniques together with empathic conversations were employed in order to gather information about their needs and experiences along the patient journey. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The focus group sessions were conducted by two members of the Outcomes’10 team and lasted for about 2 hours or until the data saturation was reached (Supplementary Table 1).

Results

Patient Care Pathway

Pre-Diagnosis Phase

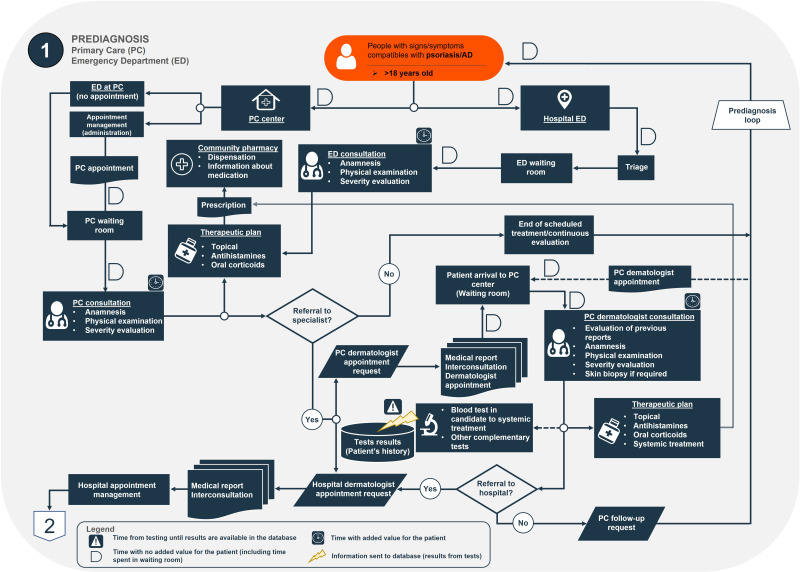

Overall, most patients with psoriasis and AD initially consult their Primary Care (PC) physician or visit the Emergency Department (ED) after the first signs or symptoms of the disease appear (Figure 1). In both PC and ED, patients can be treated by establishing a therapeutic plan. If deemed appropriate, patients with psoriasis or AD can be referred to the Dermatology Service.

Figure 1.

Detail of the pre-diagnosis phase of the care pathway for patients with psoriasis and AD.

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ED, Emergency Department; PC, Primary Care.

Patients with mild psoriasis and AD are initially managed in PC. Refractory patients or those who progress to moderate or to severe forms are referred to a dermatologist. As evidenced by the focus group with HCPs, the estimated average time from the patient’s first consultation until their referral to the Dermatology Service is five years for patients with psoriasis and three years for those with AD (particularly mild cases). This does not imply that during the time prior to referral the patients is not receiving appropriate treatment for their condition, particularly if they may have a mild form of the pathology. Furthermore, the average waiting time after referral to the Dermatology Service until the first consultation is two and three months for patients with psoriasis and with AD, respectively.

Diagnosis Phase

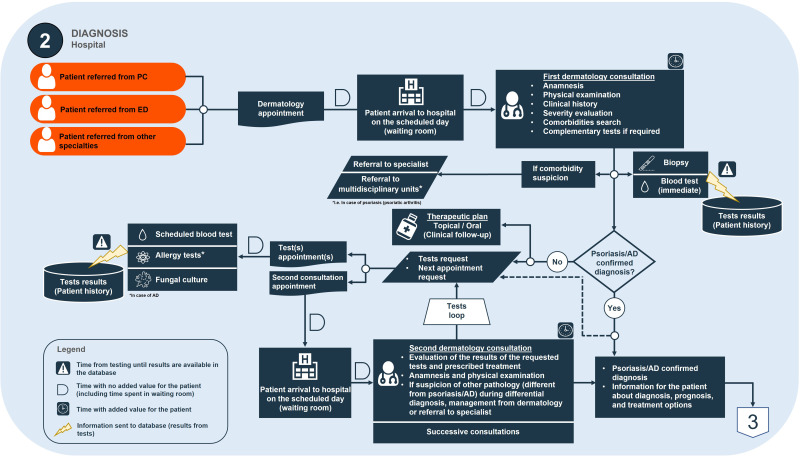

Once in the care process and after the first visit, severe patients, who have worsened or are not controlled, are referred to the hospital Dermatology Service, in charge of managing the appointment of the first consultation (Figure 2), while mild cases are followed up by the primary care physician. During the first consultation, patient’s physical examination takes place and if necessary, secondary tests are also performed. At any stage of the process, in case of comorbidity suspicion, patients can be referred to another specialist. When the diagnosis is not established in the first visit, patients are appointed for a successive consultation.

Figure 2.

Detail of the diagnosis phase of the care pathway for patients with psoriasis and AD.

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ED, Emergency Department; PC, Primary Care.

The estimated average time in the dermatology waiting room is 10 minutes, while the approximate duration of the first consultation is 15 minutes. On the other hand, the estimated average time to obtain results or tests is 1–4 weeks, and the estimated average time for the second consultation is 1–2 months.

Treatment Phase

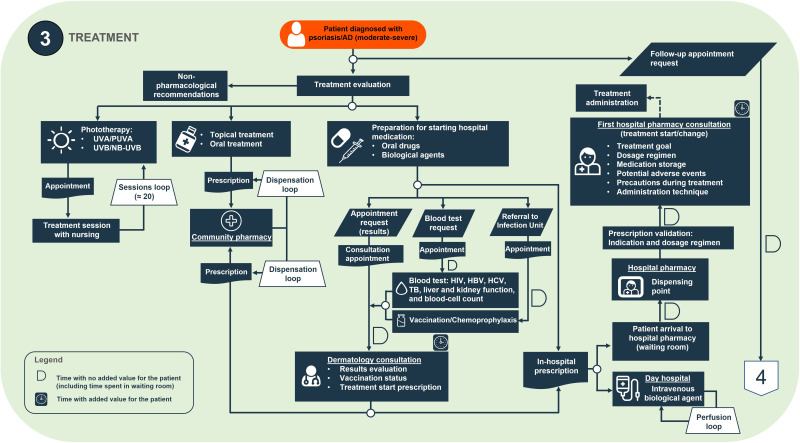

Once the diagnosis of psoriasis or AD is confirmed, patients receive all relevant information regarding treatment goals, dosage, potential adverse events as well as non-pharmacological recommendations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Detail of the treatment phase of the care pathway for patients with psoriasis and AD.

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NB-UVB, narrowband UVB phototherapy; PUVA, psoralen and ultraviolet A; TB, tuberculosis; UVA, ultraviolet A; UVB, ultraviolet B.

Prior to starting immunomodulator treatment, a test to detect potential viral infections and kidney and liver function is requested. Some treatments are dispensed in community pharmacies (topical treatments, methotrexate, cyclosporine, etc), but other are dispensed in hospital pharmacies (biological and small molecule treatments). In this case, hospital pharmacists are responsible for the dispensing of medication and also participating in treatment education.

Overall, the estimated average time for patients with psoriasis and AD from diagnosis to starting systemic treatment can be delayed up to two months.

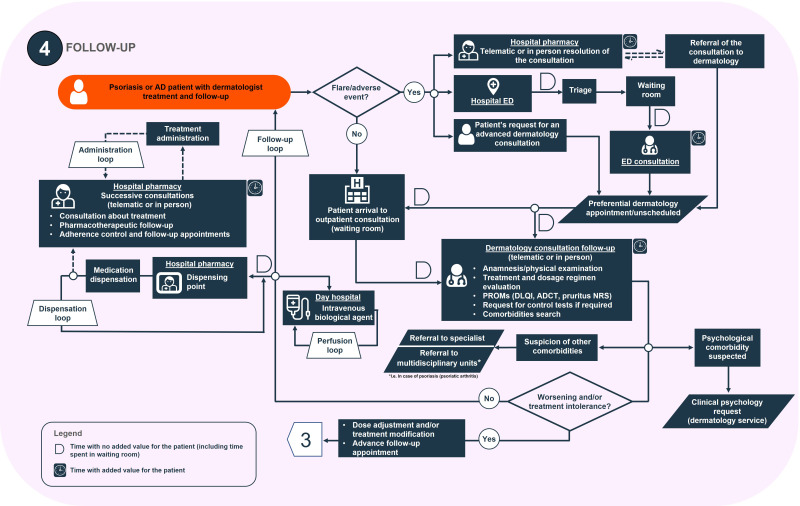

Follow-Up Phase

During the follow-up visits in the Dermatology Service, patients are examined, treatment plan is evaluated, and different patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are collected. These include the numerical rating scale (NRS) for itch in patients with AD and the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) questionnaire (Figure 4). These visits take place every six months for psoriasis patients and every 3–4 months for those with AD. However, if the patient started the treatment recently this time is reduced to 1–2 months and 1–3 months for patients with psoriasis and AD, respectively.

Figure 4.

Detail of the follow-up phase of the care pathway for patients with psoriasis and AD.

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ADCT, Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; ED, Emergency Department; NRS, numerical rating scale; PROMs, patient-reported outcomes measures.

At the hospital pharmacy, if a flare or serious adverse event is detected, pharmacists refer the patient to dermatologists or the ED. Patients attend the hospital pharmacy every 1–2 months.

Strengths and Needs Identified in the Care Pathway

The strengths and needs identified by HCPs and patients in the care pathway are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strengths and Needs in the Patient with Psoriasis and AD Journey

| Phase | Strengths | Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-diagnosis | – |

“It was no possible to make an appointment at the health centre”

“We always have to wait a long time whenever we go to the emergency room”

“Dermatological emergencies are a thing of the past. You go to the emergency room, they treat the symptoms (prick), and send you home”

“Some doctors just don’t have much empathy. They will tell you not to scratch, but that’s about it”

“It took them a while to get me in to see the specialist” |

| Diagnosis |

“I had a great experience with the dermatologists. They’re all very professional”

“In my case, the diagnosis was pretty quick” |

“It’s pretty clear that there’s room for improvement in the communication between primary care and dermatology”

“This happened years ago, but I was initially diagnosed with something else, and it took some time to receive the correct diagnosis”

“I don’t know what to do about a flare”. |

| Treatment |

“The hospital pharmacy was really helpful and professional”

“In the hospital pharmacy they explain everything very well and if necessary, they administer the treatment”. |

“Why are there so many treatments that don’t work?”

“Lack of information on eg which foods not to eat”.

“After the treatment, I got herpes, but nobody told me about the possible side effects”

“The phototherapy was helpful, but it wasn’t enough to get the disease under control”

|

| Follow-up |

“You can also contact the dermatologist by Email if you don’t want to wait for an in-person appointment”.

“They take my preferences into account as I try to lengthen my medication”.

|

“They only ask about itching as a symptom”

“It’s been about three to four months since we started treatment, and we have not had a follow-up visit yet”

“It’s tough to get in touch with the dermatologist for follow-up questions”

“It’s pretty tough to get referred to psychological care”

“If you go to the ED, then you have to make an appointment in dermatology, which will take a while. There is no possibility of referral from the ED” |

Note: Brackets indicate participants who identified the strengths and needs in the care pathway.

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ED, Emergency Department; HCPs, healthcare professionals; PC, Primary Care; PROM, patient-reported outcomes measures.

Overall, the patients participating in the study identified a higher number of needs in the care pathway than HCPs (19 and 8, respectively), while the number of strengths identified was similar in both groups (7 and 6). Furthermore, the follow-up phase was the one with the highest number of strengths (n = 7) and needs (n = 8) identified by both HCPs and patients. No strengths were highlighted for the pre-diagnosis phase.

Discussion

Patient care pathway mapping has emerged as a valuable tool in healthcare to incorporate patient’s perspective, along with HCPs experience, into the healthcare system with the main goal of improving PROMs and patient-reported experience measures.24,25

In light of the aforementioned considerations, the care pathway for patients with psoriasis and AD, including the phases of pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up, was analysed in the present study. This highlighted the main challenges identified by patients and HCPs for each phase that could improve the care process and patient experience.

Literature on dermatological care pathway is scarce. In psoriasis, a single centre experience was reported, more than a decade ago, from patient’s and physicians’ perspective.26,27 More recent studies including patients with this condition were published, although these were focused on the treatment or diagnosis.28–31 Regarding AD, one study analysed the care pathway through a Delphi, while another study developed a detailed care pathway.16,32 Finally, another study investigated patients with skin diseases journey.33

The results of our study show that patients usually attend their PC consultation or ED, where a preliminary diagnosis is obtained and later confirmed by the dermatologist. Once confirmed, a therapeutic plan is established and evaluated during successive follow-up consultations. In contrast, in other countries, such as the UK, the role of the PC physician is often to make the diagnosis and establish the most appropriate therapeutic plan.34

Patients participating in our study identified more needs in the care pathway than HCPs. Overall, patients highlighted needs such as the long waiting times and their treatment, as well effective treatments to help them manage their disease, which remain consistent with other studies.32,35 Meanwhile, HCPs participating in our study mentioned the lack of staff or specialised nurses.

We found that the pre-diagnosis and diagnosis phases are of great importance during the care process of patients with psoriasis and AD. These pathologies may resemble other skin conditions and thus, accurate diagnosis could be delayed, resulting in worse outcomes, reduced QoL, and increased economic cost.17,36 Given the difficulty in properly diagnosing these skin conditions, referral to a dermatologist is usually needed, which highlights the need of specialised care.33 Considering this, patients might seek assistance in private consultations, as reflected in the study conducted by Richard et al, in which approximately half of the participating patients were diagnosed in a private practice.33 Similarly, caregivers participating in the study developed by Roustán et al mentioned to seek for alternative care or visit the ED when symptoms worsened.32

The main goal of the treatment is to improve symptoms and establish disease control.9 However, given the multiple therapeutic options available, it is challenging for HCPs to select the best treatment for patients.16 In our study, patients mentioned that they had late access to effective treatments and received scarce information on treatment adverse events. It is noteworthy that the psoriasis patients participating in the focus groups generally had long-standing disease. On the other hand, innovative treatments for AD, have only been available for the last five years. This is in line with the results reported by Roustán et al in which participating patients claimed that first treatments prescribed were not effective, resulting in a financial burden and that potential adverse events were not explained.32

During follow-up, treatment and dosage are evaluated and adjusted if required. In our study, patients highlighted the good communication between services as well as with dermatology, which is in line with the results reported by Roustán et al.32 However, HCPs and patients disagreed on the use of PROMs; as while the former considered that PROMs were evaluated during follow-up visits, the latter mentioned that these were not used. This could be explained, at least in part, due to the high number of patients attended, which could reduce the time dedicated to each patient in the consultation. In addition, PROMs related to pruritus could be gathered by HCPs as a single question and not be perceive by patients as a PROM.

These pathologies are known to impose a great burden on patients, and some might require psychological support.9,10 A clinical psychological service was considered in our care pathway and is available for selected patients, despite stress and anxiety being common triggers for flares. In line with this, participants mentioned that is only accessible to serious cases. In this regard, it is worth noting that our centre is one of the few that has a psychodermatology unit.

Regarding the identified needs and opportunities for improvement in the care pathway, overall, the patients who participated in our study perceive long waiting times and slow referral process. They also mentioned the difficulty in making an appointment in case of a flare and the lack of dermatology emergencies. Furthermore, it is worth noting that participants only highlighted needs in the pre-diagnosis phase, suggesting that actions should be taken to improve the initial part of the care process.

On the other hand, HCPs in our study highlighted the lack of staff and nurses specialised in chronic patients receiving immunomodulator treatments. This reflects the results of the consensus reached by another panel of experts, who agreed on the fact that a multidisciplinary team should be involved in the management of patients with mild AD.16 In this regard, a study with patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis found that establishing a specialised dermatological-rheumatological management resulted in a faster diagnosis for these patients.31

Our study has some limitations. An ad-hoc questionnaire was developed for HCPs and some considerations might be missing. However, to avoid bias towards a specialty, dermatologists as well as hospital pharmacists participated in the study. Finally, the study was conducted in a single centre, thus, data extrapolation to other centres should be done with caution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the care pathway for patients with psoriasis and AD highlights different steps where the process could be optimised. Furthermore, strengths and needs in the process have been identified. Overall, this represents a starting point to design and implement strategies able to improve the care pathway of patients with psoriasis and AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all patients and professionals who participated in this study.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by Almirall, but the sponsor was not involved in the development of the study.

Abbreviations

AD, atopic dermatitis; ED, Emergency Department; HCPs, healthcare professionals; PC, primary care; PROMs, patient-reported outcomes measures; QoL, quality of life.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The study protocol (coded as IIBSP-PDA-2022-106) was approved by the local ethics committee of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain). Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to the publication of the article. The informed consent of participants included the publication of anonymised responses and direct quotes.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

HD.P. is employee of Outcomes’10, and they have received payments from the sponsor for support on design and methodology, conduction of the study and medical writing. Prof. Dr. Anna López-Ferrer reports personal fees, non-financial support from AbbVie, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Almirall, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from Leo-Pharma, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from UCB, outside the submitted work. Dr Esther Serra-Baldrich reports personal fees, non-financial support from Leo Pharma, personal fees, non-financial support from Sanofi, personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees, non-financial support from Pfizer, personal fees from Incyte, personal fees from Almirall, outside the submitted work. Dr Lluís Puig reports grants, personal fees from AbbVie, during the conduct of the study; grants, personal fees from AbbVie, grants, personal fees from Almirall, grants, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Biogen, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol-Myers-Squibb, personal fees from Fresenius-Kabi, personal fees from Horizon, personal fees from Johnson&Johnson Innovative Medicine, grants, personal fees from Leo-Pharma, grants, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Samsung Bioepis, personal fees from Sandoz, personal fees from STADA, grants, personal fees from Sun Pharma, personal fees from Takeda, grants, personal fees from UCB, outside the submitted work; and Board member, International Psoriasis Council. The authors report no other conflict of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Guttman-Yassky E, Krueger JG, Lebwohl MG. Systemic immune mechanisms in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with implications for treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(4):409–417. doi: 10.1111/exd.13336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai YC, Tsai TF. Overlapping features of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: from genetics to immunopathogenesis to phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10). doi: 10.3390/ijms23105518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen WY, Chen SC, Hsu SY, et al. Annoying psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker J. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alenazi SD. Atopic dermatitis: a brief review of recent advances in its management. Dermatol Rep. 2023;15(3):9678. doi: 10.4081/dr.2023.9678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girolomoni G, Busà VM. Flare management in atopic dermatitis: from definition to treatment. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2022;13:20406223211066728. doi: 10.1177/20406223211066728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng J, Luo S, Huang Y, Lu Q. Critical role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2017;44(8):863–872. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin M, Lee EB, Tsai TF, Wu JJ. Psoriasis and Co-morbidity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(3):adv00033. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):345–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong AW, Pathophysiology RC. Clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945–1960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czarnowicki T, Malajian D, Khattri S, et al. Petrolatum: barrier repair and antimicrobial responses underlying this “inert” moisturizer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1091–1102e1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):451–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrascosa JM, de la Cueva P, de Lucas R, et al. Patient journey in atopic dermatitis: the real-world scenario. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(5):1693–1705. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00592-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abo-Tabik M, Parisi R, Morgan C, Willis S, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM. Mapping opportunities for the earlier diagnosis of psoriasis in primary care settings in the UK: results from two matched case-control studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(724):e834–e841. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2022.0137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grada A, Muddasani S, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Peck GM. Trends in office visits for the five most common skin diseases in the United States. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(5):E82–e86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Medicines Agency. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2). 2016.

- 20.World Medical Association (WMA). WMA declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed February, 2024.

- 21.Grønkjær M, Curtis T, De Crespigny C, Delmar C. Analysing group interaction in focus group research: impact on content and the role of the moderator. Qual. Stud. 2011;2(1):16–30. doi: 10.7146/qs.v2i1.4273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang KC, Davis A. Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Fam Pract. 1995;12(4):474–475. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.4.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Inter J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies EL, Bulto LN, Walsh A, et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(1):83–100. doi: 10.1111/jan.15479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulto LN, Davies E, Kelly J, Hendriks JM. Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2024;23:429–433. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pickering H. The patient’s journey: living with psoriasis – the patient’s perspective. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(571):140. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandroff AB, Johnston GA. The patient’s journey: living with psoriasis - The doctors’ perspective. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(571):141. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tada Y, Guan J, Iwasaki R, Morita A. Treatment patterns and drug survival for generalized pustular psoriasis: a patient journey study using a Japanese claims database. J Dermatol. 2024;51:391–402. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.17097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu JJ, Lu M, Veverka KA, et al. The journey for US psoriasis patients prescribed a topical: a retrospective database evaluation of patient progression to oral and/or biologic treatment. J Dermatol Treat. 2019;30(5):446–453. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1529386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Reek J, Seyger MMB, van Lümig PPM, et al. The journey of adult psoriasis patients towards biologics: past and present – results from the BioCAPTURE registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(4):615–623. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziob J, Behning C, Brossart P, Bieber T, Wilsmann-Theis D, Schäfer VS. Specialized dermatological-rheumatological patient management improves diagnostic outcome and patient journey in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a four-year analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s41927-021-00217-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roustán G, Loro M, Rosell Á, et al. Development of a patient journey map for improving patient experience and quality of atopic dermatitis care. Dermatol Ther. 2024;14:505–519. doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01100-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richard MA, Paul C, Nijsten T, et al. The journey of patients with skin diseases from the first consultation to the diagnosis in a representative sample of the European general population from the EADV burden of skin diseases study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37 Suppl 7:17–24. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Roux E, Edwards PJ, Sanderson E, Barnes RK, Ridd MJ. The content and conduct of GP consultations for dermatology problems: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(699):e723–e730. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X712577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldman SR, Chan AWM, Ammoury A, et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives of the atopic dermatitis journey. J Dermatol Treat. 2024;35(1):2315145. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2024.2315145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weidinger S, Nosbaum A, Simpson E, Guttman E. Good practice intervention for clinical assessment and diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: findings from the atopic dermatitis quality of care initiative. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(3):e15259. doi: 10.1111/dth.15259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]