Abstract

Organ/space surgical site infection (SSI) are common after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). There is limited research on the clinical impact of intraoperative lavage fluid contamination in patients undergoing PD. One hundred five patients who underwent PD between August 2022 and July 2023 were retrospectively enrolled. The intraoperative bile and peritoneal lavage were collected for bacterial culture. Postoperative drainage bacterial cultures were performed every 2–3 days thereafter until drains were all removed. The bacteria isolated from intraoperative lavage fluid, intraoperative bile, and postoperative drainage fluid were examined in detail. The risk factors associated with positive intraoperative lavage fluid culture were analyzed through both univariate and multivariate analyses. Organ/space SSI occurred in 59(56.2%) of the 105 patients. The positivity rates of cultures in intraoperative lavage fluid, intraoperative bile, and postoperative drainage fluid were found to be 41.0%, 67.6%, and 84.8%, respectively. Patients with positive intraoperative lavage fluid culture had a significantly higher occurrence of organ/space SSI compared to the negative group (69.0% vs. 29.4%, P < 0.001). Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) was identified as the only independent risk factor for the contamination of intraoperative lavage fluid (OR = 7.687, 95% CI: 2.164–27.300, P = 0.002). K. pneumoniae was the most common isolates both in the intraoperative lavage fluid and postoperative drainage fluid. Intraoperative lavage fluid contamination closely correlated with organ/space SSI after PD. Meanwhile, PBD was the only risk factor for the contamination of intraoperative lavage fluid.

Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Surgical site infection, Intraoperative lavage

Subject terms: Microbiology, Diseases, Medical research

Introduction

Over the past decade, dramatic advances in surgical technique and perioperative management have transformed pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) into a relatively safe surgery in high-volume centers. However, the incidence of postoperative complications, including clinically relevant pancreatic fistula (CR-POPF) and organ/space surgical site infection (SSI), remains high, ranging from 25–65%1,2. As reported in several previous studies, intraoperative bile contamination or postoperative drainage fluid contamination has an adverse impact on postoperative complications after PD including organ/space SSI1,3,4. As the final step of PD, intraoperative lavage was designed to isolate and eliminate potential bacterial contamination as well as other substances that may facilitate microorganism proliferation5. Current studies on the clinical significance of intraoperative lavage fluid culture have focused on appendicitis, peritonitis and colorectal resection6–9. Nevertherless, there is still a lack of research on the clinical implications of intraoperative lavage fluid culture in patients undergoing PD.

Given the significant prevalence of organ/space SSI following PD and the paucity of studies on intraoperative lavage fluid contamination, the objective of this study was to investigate the significance of intraoperative lavage fluid contamination on postoperative complications following PD.

Methods

Patients

All patients who underwent PD between August 2022 and July 2023 were enrolled retrospectively in the Department of Pancreatic and Metabolic Surgery, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients who underwent PD; (b) no history of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and (c) > 18 years of age. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) underwent simultaneous hepatic or colon resection; (b) received emergency surgery for trauma; and (c) clinical data were incomplete. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (2021-271-01) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Surgical procedures and perioperative management

The modified Child’s method was applied to the standard procedure for PD. It was common practice to use manual duct-to-mucosal, end-to-side, and double-layer interrupted anastomosis. The details of hepaticojejunostomy, gastrojejunostomy and the indications of preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) were described previously10. The intraoperative bile was obtained for culture when the bile duct was transected. After the reconstruction of the digestive tract, surgeons changed the sterile gloves as well as the suction device. Intraoperative peritoneal lavage was conducted using 3000 ml saline, and the final fluid from the lavage was collected for bacterial culture.

Prophylactic antibiotics were routinely prescribed as third-generation cephalosporins routinely, such as ceftriaxone, and administered until postoperative day (POD) 2. In patients with positive bile cultures from PBD and resistance to ceftriaxone, the prophylactic antibiotics were selected based on the antimicrobial susceptibility. Postoperative drainage fluid tests, including amylase and bacterial culture, were performed on POD 1, 3 and 5 and every 2–3 days thereafter until drains were all removed.

Clinical data collection and definition of complication

Demographic data, preoperative laboratory data, intraoperative variables, pathological diagnosis and postoperative complications were all collected. The occurrence of SSI, including incisional and organ/space SSI, was diagnosed according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines11,12. Postoperative complications’ severity was assessed by the Clavien–Dindo classification, with major complications defined as grade ≥ III13. CR-POPF, biliary leakage (BL), delayed gastric emptying (DGE), chyle leakage (CL) and post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) were diagnosed according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS)14–18.

Statistical analysis

Clinical data analysis was conducted by SPSS 26.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc.). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages and analyzed by the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables, which distributed normally, were expressed by mean and standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by the independent t-test. Continuous variables that were distributed non-normally were shown as median (interquartile range, IQR) and compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. Variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis entered the multivariate logistic regression model. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were obtained. A P value of < 0.05, two sides, was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

105 patients were enrolled into the study consist of 60(57.1%) men and 45(42.9%) women with a median age of 63 years. The clinical and baseline characteristics were shown in Table 1. 102(97.1%) patients were treated by open technique and PBD was performed in 40(38.1%) patients. There were 32(30.5%) patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), 41(39.0%) with Vater’s ampullary carcinoma (VAC), and 8(7.6%) with distal cholangiocarcinoma(DCC). The positivity rates of cultures in intraoperative lavage fluid, intraoperative bile, and postoperative drainage fluid were found to be 41.0%, 67.6%, and 84.8%, respectively.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics.

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 105) |

|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR), years | 63.0 (54.0–71.0) |

| BMI (mean ± SD), kg/m2 | 22.4 ± 2.6 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 60 (57.1) |

| Female | 45 (42.9) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 34 (32.4) |

| DM, n (%) | 17 (16.2) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 34 (32.4) |

| Drinking, n (%) | 26 (24.8) |

| Preoperative jaundice, n (%) | 47 (44.8) |

| PBD, n (%) | 40 (38.1) |

| TB (median, IQR), µmol/L | 15.7 (8.0–79.1) |

| Alb (mean ± SD), g/L | 38.3 ± 3.1 |

| CRP (median, IQR), mg/L | 3.9 (2.6–7.7) |

| Hemoglobin (mean ± SD), g/L | 119.3 ± 20.1 |

| Pathology, n (%) | |

| PDAC | 32 (30.5) |

| DCC | 8 (7.6) |

| VAC | 41 (39.0) |

| IPMN | 4 (3.8) |

| SPN | 2 (1.9) |

| SCN | 2 (1.9) |

| pNET | 3 (2.9) |

| Others | 13 (11.4) |

| Type of operation, n (%) | |

| Open | 102 (97.1) |

| Laparoscopic | 3 (2.9) |

| Vessel resection, n (%) | |

| Yes | 8 (7.6) |

| No | 97 (92.4) |

| Pancreatic consistency, n (%) | |

| Hard | 17 (83.8) |

| Soft | 88 (16.2) |

| Diameter of MPD (median, IQR), mm | 3.0 (2.0–3.0) |

| Operation time (median, IQR), min | 300.0 (240.0-352.5) |

| Blood loss volume (median, IQR), ml | 300.0 (200.0-400.0) |

| Blood transfusion (median, IQR), ml | 0.0 (0.0-400.0) |

| Positive intraoperative bile culture, n (%) | 43 (41.0) |

| Positive intraoperative lavage fluid culture, n (%) | 71 (67.6) |

| Positive postoperative fluid culture, n (%) | 89 (84.8) |

IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; PBD: preoperative biliary drainage; TB: total bilirubin, Alb: albumin; PD: pancreaticoduodenectomy; PPPD: pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy; MPD: main pancreatic duct; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; DCC: distal cholangiocarcinoma; VAC: Vater’s ampullary carcinoma; IPMN: intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; SPN: solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas; SCN: pancreatic serous cystadenoma; pNET: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Surgical outcomes and risk factors for positive lavage fluid culture

All patients were classified into two groups as negative lavage fluid culture group (n = 34, 32.4%) and positive lavage fluid culture group (n = 71, 67.6%). The most prevalent and perilous postoperative complications were listed in Table 2. Organ/space SSI occurred in 59 (56.2%) of the 105 patients. Patients with positive intraoperative lavage fluid culture had a significantly higher occurrence of organ/space SSI compared to the negative group (69.0% vs. 29.4%, P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the rates of CR-POPF (35.2% vs. 14.7%, P = 0.030) and major complications (21.7% vs. 0.0%, P = 0.004) were significantly higher in the group with positive intraoperative lavage fluid culture.

Table 2.

Surgical outcomes according to the bacterial culture from intraoperative lavage fluid.

| Complications | All patients (n = 105) | Lavage fluid culture negative (n = 34) | Lavage fluid culture positive (n = 71) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe complications | ||||

| Pancreatic fistula, n (%) | 0.030 | |||

| Non-PF/biochemical fistula | 75 (71.4) | 22 (85.3) | 53 (64.8) | |

| CR-POPF | 30 (28.6) | 5 (14.7) | 25 (35.2) | |

| Major complication, n (%) | 15 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (21.7) | 0.004 |

| PPH, n (%) | 1 0(9.5) | 1 (2.9) | 9 (12.7) | 0.161 |

| BL, n (%) | 12 (11.4) | 4 (11.8) | 8 (11.3) | 0.940 |

| Organ/space SSI, n (%) | 59 (56.2) | 10 (29.4) | 49 (69.0) | < 0.001 |

| Non-severe complication | ||||

| Incisional SSI, n (%) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (2.8) | 1.000 |

| DGE, n (%) | 29 (27.6) | 13 (38.2) | 16 (22.5) | 0.092 |

| CL, n (%) | 18 (17.1) | 5 (14.7) | 13 (18.3) | 0.647 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 31.0 (23.0–27.0) | 26.0 (20.8–35.5) | 32.0 (24.0–37.0) | 0.052 |

PF: pancreatic fistula; CR-POPF: Clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (Grade B/ C); BL: biliary leakage; CL: chyle leakage; PPH: post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage; DGE: delayed gastric emptying; SSI: surgical site infection.

The univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for positive intraoperative lavage fluid culture were shown in Table 3. PBD was identified as the only independent risk factor for the contamination of intraoperative lavage fluid (OR = 7.687, 95% CI: 2.164–27.300, P = 0.002).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the contamination of intraoperative lavage fluid.

| Variables | Lavage fluid culture negative (n = 34) | Lavage fluid culture positive (n = 71) | P | OR (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR), years | 59.5 (52.0-68.5) | 65.0 (55.0–71.0) | 0.024 | 1.001 (0.957–1.046) | 0.979 |

| BMI (mean ± SD), kg/m2 | 22.3 ± 2.6 | 22.5 ± 2.7 | 0.651 | ||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.857 | ||||

| Male | 19 (55.9) | 41 (57.7) | |||

| Female | 15 (44.1) | 30 (42.3) | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 10 (29.4) | 24 (33.8) | 0.653 | ||

| DM, n (%) | 6 (17.6) | 11 (15.5) | 0.779 | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | 9 (26.5) | 25 (35.2) | 0.370 | ||

| Drinking, n (%) | 8 (23.5) | 18 (25.4) | 0.840 | ||

| Preoperative jaundice, n (%) | 14 (41.2) | 33 (46.5) | 0.609 | ||

| PBD, n (%) | 5 (14.7) | 35 (49.3) | 0.001 | 7.687 (2.164–27.300) | 0.002 |

| TB (median, IQR), µmol/L | 15.7 (9.1–94.1) | 15.7 (8.3–72.9) | 0.007 | 0.992 (0.983–1.087) | 0.095 |

| Alb (mean ± SD), g/L | 38.5 ± 3.0 | 38.3 ± 3.2 | 0.719 | ||

| CRP (median, IQR), mg/L | 3.6 (2.5–5.1) | 4.1 (2.8–10.2) | 0.002 | 1.083 (0.986–1.189) | 0.094 |

| Hb (mean ± SD), g/L | 122.6 ± 17.9 | 117.7 ± 20.9 | 0.242 | ||

| Pathology, n (%) | 0.232 | ||||

| PDAC | 13 (38.2) | 19 (26.8) | |||

| Others | 21 (61.8) | 52 (73.2) | |||

| Type of operation, n (%) | 0.549 | ||||

| Open | 34 (100.0) | 68 (95.8) | |||

| Laparoscopic | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.2) | |||

| Vessel resection, n (%) | 0.643 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (5.9) | 6 (8.5) | |||

| No | 32 (94.1) | 65 (91.5) | |||

| Pancreatic consistency, n (%) | 0.647 | ||||

| Hard | 5 (14.7) | 13 (18.3) | |||

| Soft | 29 (85.3) | 58 (81.7) | |||

| Diameter of MPD (median, IQR), mm | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 0.841 | ||

| Operation time (median, IQR), min | 292.5 (203.8–342.5) | 300.0(250.0–365.0) | 0.618 | ||

| Blood loss volume (median, IQR), ml | 300.0 (200.0–400.0) | 300.0 (200.0–500.0) | 0.388 | ||

| Blood transfusion (median, IQR), ml | 300.0 (200.0–400.0) | 300.0 (200.0–500.0) | 0.323 |

POD: postoperative day; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; PBD: preoperative biliary drainage; TB: total bilirubin, Hb: hemoglobin; Alb: albumin; PD: pancreaticoduodenectomy; PPPD: pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy; MPD: main pancreatic duct; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Detail of bacterial isolates

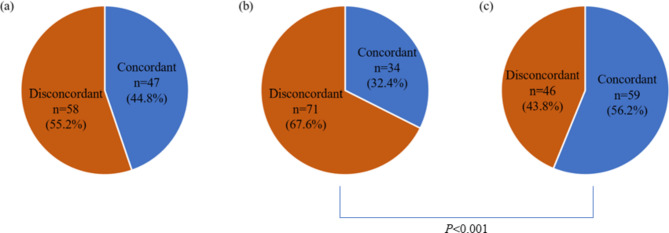

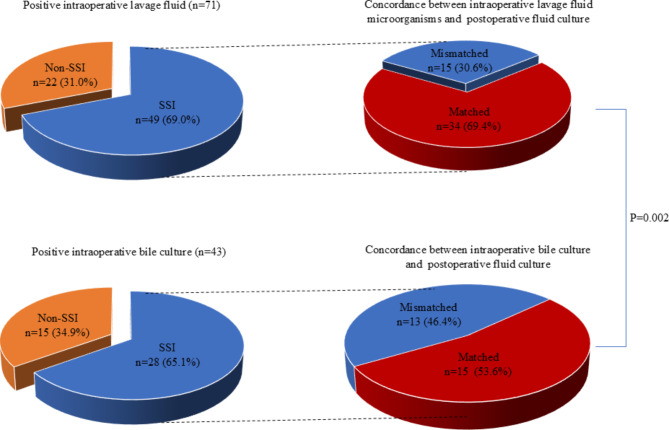

The bacteria isolated from intraoperative lavage fluid, intraoperative bile and postoperative drainage fluid were shown in Table 4. The most common cultured microorganisms of intraoperative bile were E. faecalis (n = 9, 8.6%), followed by K. pneumoniae (n = 7, 6.7%), E. faecium (n = 5, 4.8%) and E. coli (n = 5, 4.8%). K. pneumoniae was the most common isolates both in the intraoperative lavage fluid and postoperative drainage fluid. Other common bacteria identified from intraoperative lavage fluid were E. faecalis (n = 8, 7.6%), E. coli (n = 8, 7.6%) and E. cloacae (n = 6, 5.7%). Meanwhile, in addition to K. pneumoniae (n = 14, 14.3%), E. faecalis (n = 13, 12.4%), S. haemolyticus (n = 13, 12.4%), Fungus (n = 13, 12.4%) and E. cloacae (n = 8, 7.6%) are more prevalent in postoperative drainage fluid. There were 47(44.8%) patients showing the same result in both intraoperative bile culture and intraoperative lavage fluid. Meanwhile, the concordant rate between intraoperative lavage fluid and postoperative fluid was significantly higher than that between intraoperative bile culture and postoperative fluid (56.2% vs. 32.4%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Among the 71 patients with positive intraoperative lavage fluid, SSI occurred in 49(69.0%) patients. The concordance between intraoperative lavage fluid and positive fluid culture was 69.4% among these 49 patients. 28(65.1%) patients underwent organ/space SSI in the 43 patients with contaminated intraoperative bile. 53.6% of these 28 patients had similar microorganisms between intraoperative and postoperative drainage fluid. The concordant rate between intraoperative lavage fluid and postoperative fluid in patients suffered from organ/space SSI was significantly higher than that between intraoperative bile and postoperative drain fluid (69.4% vs. 53.6%, P = 0.002) (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Details of bacterial cultures.

| Microorganisms | Intraoperative bile culture (n = 105) | Intraoperative lavage fluid culture (n = 105) | Postoperative fluid culture (n = 105) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymicrobial mixed flora, n (%) | 14 (13.3) | 18 (17.1) | 58 (55.2) |

| K. pneumoniae, n (%) | 7 (6.7) | 10 (9.5) | 14 (14.3) |

| E. faecalis, n (%) | 9 (8.6) | 8 (7.6) | 13 (12.4) |

| E. faecium, n (%) | 5 (4.8) | 3 (2.9) | 7 (6.7) |

| S. haemolyticus, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 13 (12.4) |

| E. coli, n (%) | 5 (4.8) | 8 (7.6) | 10 (9.5) |

| Fungus, n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (1.0) | 12 (11.4) |

| E. cloacae, n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 6 (5.7) | 8 (7.6) |

| P. aeruginosa, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| A. baumannii, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.9) | 5 (4.8) |

| S. aureus, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (7.6) |

Fig. 1.

(a) Intraoperative bile vs. intraoperative lavage fluid; (b) intraoperative bile vs. postoperative fluid; (c) intraoperative lavage fluid vs. postoperative fluid.

Fig. 2.

(a) Positive intraoperative lavage fluid (n = 71). Concordance between intraoperative lavage fluid microorganisms and postoperative fluid culture; (b) positive intraoperative bile culture (n = 43). Concordance between intraoperative bile culture and postoperative fluid culture.

Discussion

The current study yielded 3 primary findings. First, there was a significant correlation between the contamination of intraoperative lavage fluid and organ/space SSI, as well as the incidence of CR-POPF and major complications after PD. Second, the microorganisms isolated from lavage fluid matched the bacteria responsible for organ/space SSI in most cases. Third, PBD was the independent risk factor for positive lavage culture.

Recent studies indicated that positive culture of intraoperative ascitic fluid may correlate with an increased risk of postoperative complications following PD. Matsuki et al. demonstrated that the incidence of positive lavage culture was 44.9%, which correlates with the occurrence of CR-POPF and organ/space SSI19. Sugiura et al. found that the contamination of intraoperative lavage fluid increased the occurrence of organ/space SSI and CR-POPF after PD5. In the present study, the incidence of CR-POPF was significantly higher in patients with positive lavage culture, implying that bacterial contamination may induced CR-POPF, although the specific mechanism by which bacteria influences the development of CR-POPF. Our institution conducted peritoneal lavage with 3000 ml saline at the end of operation routinely in the attempt to eliminate the bacteria inoculation and sources that may serve as potential culture medium for microorganisms. However, it was noteworthy that the positive rate of intraoperative lavage fluid culture was remain as high as 65.7% in current study, suggesting a correlation between positive lavage fluid and postoperative organ/space SSI, which was consistent with previous reports. Consequently, in light of the aforementioned findings, it is imperative to minimized intraoperative bacterial contamination and obtain lavage fluid for bacterial culture. This approach aims to alter the treating surgeon to be more vigilant for postoperative complications and modify the antibiotic administration in the early postoperative phase based on intraoperative fluid microbiologic profile and their sensitivity patterns when clinically indicated.

In several previous studies3,20,21, bacterobilia has frequently been identified as the origin of the causative organism responsible for organ/space SSI following PD. Nevertheless, few report the concordance between bile culture and SSI, as well as intraoperative lavage culture and SSI. In a prospective study of hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery, Yasukawa et al.22 identified that individuals with positive lavage fluid culture exhibited a significantly higher incidence of both incisional SSI and organ/space SSI than patients with a negative lavage fluid culture. Meanwhile, they found that 32.7% of patients were consistent with the isolates detected in the lavage fluid and in organ/space SSI, as well as 10.1% were consistent with the isolates detected in the preoperative bile and in organ/space SSI. In the present study, the microorganisms cultured from intraoperative lavage fluid were consistent with postoperative drain fluid in 69.4% of patients with organ/space SSI. On the contrary, only 53.6% of the isolates cultured from intraoperative bile corresponded to those isolated from postoperative drain fluid. These results indicated that not all of the bacteria contributing to organ/space SSI were derived from biliary infection. Other potential sources of bacteria contributing to organ/space SSI could be leakage during gastrointestinal reconstruction or retrograde infection from the postoperative drainage tube. In our study, the concordance between intraoperative bile and postoperative ascites culture was only 32.4%, whereas the concordance between intraoperative peritoneal lavage fluid and postoperative ascites culture results was 56.2%. This indicated that intraoperative bile culture may not be sufficient for surveillance of organ/space SSI after PD. Given the high concordance between intraoperative and postoperative ascites culture, as well as the association between intraoperative ascites contamination and subsequent postoperative complications, including organ/space SSI, we deemed it essential to retain intraoperative lavage fluid for bacterial culture in order to adjust the appropriate administration of antibiotics during the early postoperative period.

PBD was performed as a classical method to decompress biliary obstruction and improve hepatic function for patients with jaundice before PD23. According to our prior studies, PBD had a significant negative effect on several postoperative complications after PD, especially organ/space SSI10,24,25. In current, PBD was identified as the only independent risk factor for the contamination of lavage fluid. It was an invasive procedure that induced retrograde infection of the biliary tract and pancreas from the gastrointestinal tract26. On the other hand, PBD may also contribute to a state of inflammation and edema around the surgical region, which escalates the complexity and extends the duration of the surgery27,28. These might indirectly contribute to intraoperative bacterial contamination, which in turn leads to organ/space SSI. Presently, there is still a contentious debate on whether PBD routinely improves surgical outcomes. A few studies have suggested that PBD decreases the occurrence of morbidity and mortality after PD29,30. Nevertheless, various retrospective analyses and meta-analyses of randomized trials have indicated that routine PBD elevates the risk of overall postoperative complications, including organ/space SSI28,31,32. In conjunction with the results of our study, the indication for PBD should be carefully evaluated and performed in selected patients undergoing PD. Simultaneously, routine intraoperative bile cultures help to some extent in monitoring organ/space SSI following PD.

The current study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center retrospective study, which was accompanied by selection bias. Therefore, further multicenter and randomized controlled trials are essential to confirm the significance of intraoperative lavage fluid on organ/space SSI. Second, the sample was small which may result in insufficient statistical efficiency. Then, the study suffered from bacteriological susceptibility which was more valuable for clinical management of organ/space SSI.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the outcomes of our study showed that intraoperative lavage fluid contamination closely correlated with organ/space SSI after PD. Further, limiting the indication of PBD may decrease the occurrence of positive intraoperative ascites culture. At the same time, intraoperative lavage fluid culture may be a useful adjunct to modify the antibiotic agents in the early postoperative period when clinically indicated.

Acknowledgements

We would like to offer our special thanks to members of the multidisciplinary biliopancreatic cancer team of the Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, The Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School for their guidance.

Author contributions

L.M. and X.F. designed this study. X.F. and C.L. supervised this study. Y.Y., J.S., C.L., H.C., G.L. and C.C. collected the data. Y.Y., X.F. and J.S. performed statistical analyses in this study. Y.Y. and J.S. prepared the manuscript. L.M. and Y.Q. revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of this study.

Funding

Nanjing Health Technology Development Special Fund (No. ZKX22023).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (2021-271-01). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yifei Yang and Jianjie Sheng.

Contributor Information

Chang Liu, Email: liuchangbio@163.com.

Xu Fu, Email: fuxunju2012@163.com.

References

- 1.Lopez, P. et al. The role of clinically relevant intra-abdominal collections after pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical impact and predictors. A retrospective analysis from a European tertiary centre. Langenbecks Arch. Surg.409, 21 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman, S. W. & Zarzaur, B. L. Intra-abdominal sepsis following pancreatic resection: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, microbiology, management, and outcome. Am. Surg.74, 572–578 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parapini, M. L. et al. The association between bacterobilia and the risk of postoperative complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxf.)24, 277–285 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suenaga, M. et al. Impact of preoperative occult-bacterial translocation on surgical site infection in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg.232, 298–306 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugiura, T. et al. Impact of bacterial contamination of the abdominal cavity during pancreaticoduodenectomy on surgical-site infection. Br. J. Surg.102, 1561–1566 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou, Q. et al. Effectiveness of intraoperative peritoneal lavage with saline in patient with intra-abdominal infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Emerg. Surg.18, 24 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Platell, C., Papadimitriou, J. M. & Hall, J. C. The influence of lavage on peritonitis. J. Am. Coll. Surg.191, 672–680 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qadan, M., Dajani, D., Dickinson, A. & Polk, H. C. Jr. Meta-analysis of the effect of peritoneal lavage on survival in experimental peritonitis. Br. J. Surg.97, 151–159 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minervini, S. et al. Prophylactic saline peritoneal lavage in elective colorectal operations. Dis. Colon Rectum. 23, 392–394 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang, Y., Fu, X., Cai, Z., Qiu, Y. & Mao, L. The occurrence of Klebsiella pneumoniae in drainage fluid after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and clinical impacts. Front. Microbiol.12, 763296 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horan, T. C., Gaynes, R. P., Martone, W. J., Jarvis, W. R. & Emori, T. G. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol.13, 606–608 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horan, T. C., Andrus, M. & Dudeck, M. A. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am. J. Infect. Control36, 309–332 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P. A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg.240, 205–213 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wente, M. N. et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery142, 20–25 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wente, M. N. et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS). Surgery142, 761–768 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassi, C. et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery161, 584–591 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besselink, M. G. et al. Definition and classification of chyle leak after pancreatic operation: a consensus statement by the International Study Group on pancreatic surgery. Surgery161, 365–372 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch, M. et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver surgery. Surgery149, 680–688 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuki, R. et al. Double-volume intraoperative lavage reduce bacterial contamination after Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am. Surg.87, 1025–1031 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asukai, K. et al. The utility of bile juice culture analysis for the management of postoperative infection after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery173, 1039–1044 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maatman, T. K. et al. Does the microbiology of bactibilia drive postoperative complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. J. Gastrointest. Surg.24, 2544–2550 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasukawa, K. et al. Impact of large amount of intra-abdominal lavage on surveillance of surgical site infection after hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery: a prospective cohort study. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci.30, 705–713 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, P. J. et al. Preoperative biliary drainage in resectable pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. HPB (Oxf.)20, 477–486 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu, X., Yang, Y., Mao, L. & Qiu, Y. Risk factors and microbial spectrum for infectious complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Gland Surg.10, 3222–3232 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu, L. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting post-operative abdominal infection in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Clin. Chim. Acta534, 57–64 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Limongelli, P. et al. Correlation between preoperative biliary drainage, bile duct contamination, and postoperative outcomes for pancreatic surgery. Surgery142, 313–318 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coates, J. M. et al. Negligible effect of selective preoperative biliary drainage on perioperative resuscitation, morbidity, and mortality in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch. Surg.144, 841–847 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheufele, F. et al. Preoperative biliary stenting versus operation first in jaundiced patients due to malignant lesions in the pancreatic head: a meta-analysis of current literature. Surgery161, 939–950 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen, Z. et al. Preoperative biliary drainage of severely obstructive jaundiced patients decreases overall postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a retrospective and propensity score-matched analysis. Pancreatology20, 529–536 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bortolotti, P. et al. High incidence of postoperative infections after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a need for perioperative anti-infectious strategies. Infect. Dis. Now51, 456–463 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akashi, M. et al. Preoperative cholangitis is associated with increased surgical site infection following pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci.27, 640–647 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang, Y. et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on safety and efficacy of biliary drainage before surgery for obstructive jaundice. Br. J. Surg.100, 1589–1596 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.